Abstract

The information society is increasingly more dependent on Information Security Management Systems (ISMSs), and the availability of these kinds of systems is now vital for the development of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs). However, these companies require ISMSs that have been adapted to their special features, and which are optimized as regards the resources needed to deploy and maintain them. This article shows how important the security culture within ISMSs is for SMEs, and how the concept of security culture has been introduced into a security management methodology (MARISMA is a Methodology for “Information Security Management System in SMEs” developed by the Sicaman Nuevas Tecnologías Company, Research Group GSyA and Alarcos of the University of Castilla-La Mancha.) for SMEs. This model is currently being directly applied to real cases, thus allowing a steady improvement to be made to its implementation.

1. Introduction

An Information Security Management System (ISMS) can be defined as a management system that is used to establish and maintain a secure environment for information. The principal objective of ISMSs is to tackle the putting into practice and maintenance of the processes and procedures needed to manage the security of information technologies [1,2,3,4,5]. Dhillon [6] states that ISMSs are concerned not only with the security of information but also include the management of that information’s formal and informal aspects [7]. These actions include the identification of the information’s security needs and the putting into practice of strategies in order to satisfy those needs, measure the results and improve the protection strategies [8,9].

Experts have identified various approaches based on policies, the raising of awareness, training and education [10,11,12,13] in order to help companies create an information security culture. However, management initiatives in themselves will not have a significant influence on employees’ behavior [14] and, according to Schultz [15], it is necessary to pay particular attention to the human factor.

Furthermore, when implementing ISMSs, the majority of models have focused on technical and management aspects, and have virtually ignored the third aspect, which is institutional and has come to be of particular relevance in recent years [1,8,16]. Von Solms [17] therefore states that information security should not focus solely on these two orientations (technical and management), but should be completed with a third orientation (institutional, or the security culture). The principal function of each orientation would therefore be:

- Technical Orientation: This deals with the technical management of information security through the use of computer systems, such as authentication and access control services.

- Management Orientation: This began when the top management became involved in information security with the evolution of the Internet and electronic business activities, and includes tasks regarding the preparation of information security, policies, procedures and methods, along with the designation of a person who is responsible for security.

- Institutional tendency: this is parallel to the first and second orientations and includes the creation of a corporative security culture covering the standardization, certification, measurement and concern about the human aspect in information security.

The objective of institutionalization is to construct an information security culture, such that it becomes a natural part of all the organization’s employees’ daily activities [17,18]. The objective of developing this information security culture is to control the inappropriate use of information by the information system users [19,20]. In an information security culture, the employees’ behavior contributes towards the protection of data, information and knowledge [20], and information security becomes a natural part of their daily activities [11]. The potential benefit of adopting an information security management culture was also demonstrated by Galletta and Polak [21], who showed that between 20%–50% of employees reveal the company’s information or make inappropriate use of the information system [22,23,24]. According to Ernst and Young [25], an important advance has taken place with regard to the establishment of a security culture over the last few years, but much work must still be done.

Many governments have made tremendous efforts in an attempt to improve their companies’ levels of security. The objective of the information security policies (DTI) [26] group in the United Kingdom is therefore to help companies manage their information security in an effective manner and provide a set of documents that will serve as a starting point. “The OCDE’s guidelines for information and communication system security” [27] state that there is a need for a better consciousness and understanding of security-related questions, along with the need to develop a “security culture”.

The decision was therefore made to carry out this research in order to find a solution to the problems confronted by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) when implementing the “security culture”. The system presented is simple, progressive and quantifiable, and complies with the OCDE guidelines. This research was developed using the ‘Action Research’ scientific method, which allowed us to analyze the problem in question and refine the solution to it.

The paper continues in Section 2 with a brief description of the scientific method used in this research, along with the main methodologies and models employed to manage security. All of these processes focus on the importance of the security culture in ISMSs. Section 3 contains a brief introduction to our proposal for a methodology for security management, which is oriented towards SMEs and is denominated as MARISMA. An analysis of how the concept of security culture has been included in our methodology is carried out in Section 4, while the practical application of the concept of security culture is shown in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 shows the principal advantages that SMEs have stated that the process has, in addition to the work that will be developed in the future.

2. State of the Art

The research into the “security culture” shown in this paper was principally carried out using the “Action Research” scientific research method. In this subsection we first analyze this method and its application to the work carried out, while in the second subsection we analyze some of the research into the security culture in SMEs that we consider to be of interest to our research.

2.1. The Action Research Method

Qualitative research methods, and particularly, Action Research (AR), have in recent years attracted the attention and gained the acceptance of the scientific community related to information systems [28,29,30].

Action Research does not refer to a specific research method but rather to a class of methods that have the following in common: (i) orientation towards action and change; (ii) focus on a problem; (iii) an ‘organic’ modeling process that encompasses systematic and sometimes iterative steps and, (iv) collaboration among participants.

The term ‘action research’, was first coined by Kurt Lewin in 1946 in his work entitled ‘Action research and minority problems’. The AR method is characterized as being comparative research into the conditions and effects of various types of research and social action, in which the most prominent aspect is social action using a spiral process consisting of several steps, each of which is composed of various cycles: planning, action and the search for facts regarding the results of the action [31,32].

The application of this method is directly related to the objective pursued in this research: defining a methodology and a security management model for SMEs.

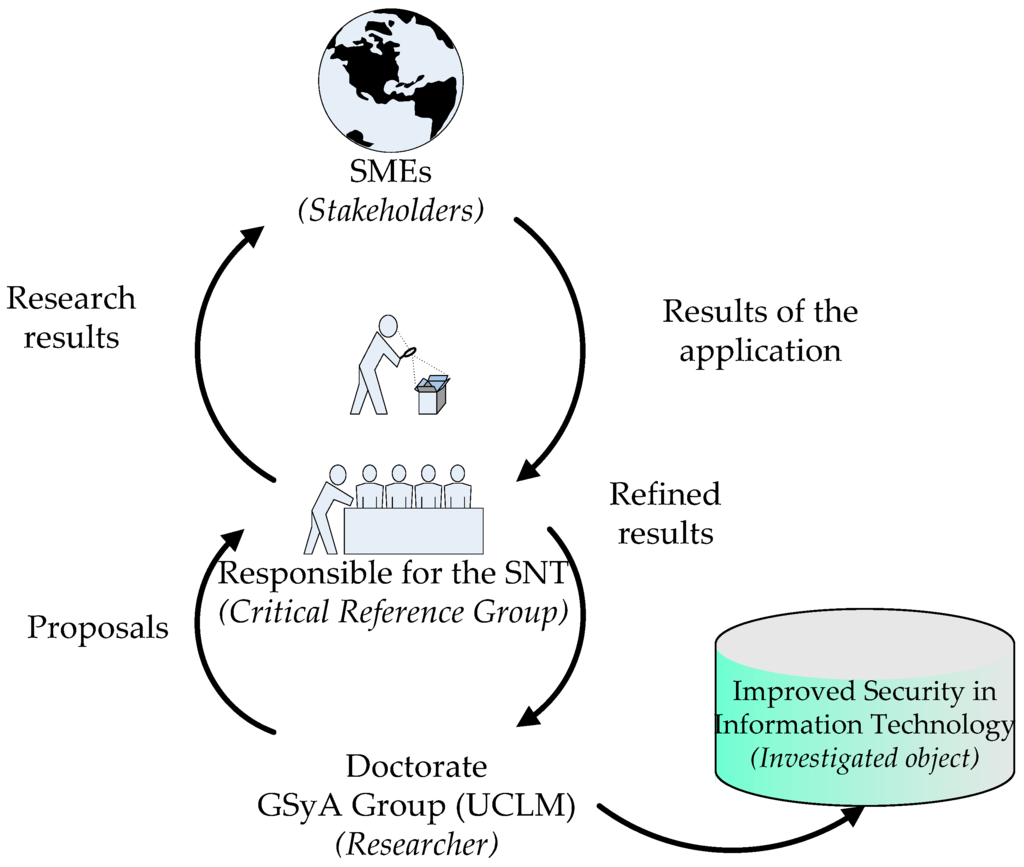

The research has been carried out by applying the action-research method in its participant variant, i.e., that in which the critical reference group puts the recommendations made by the researcher into practice, and shares the effects and results with that researcher. The following participants were therefore defined:

- The researcher, which is in this case the GSyA Research Group, made up of professors at the School of Computer Sciences at the University of Castilla-La Mancha in Ciudad Real, Spain.

- The object being researched, i.e., the problem to be resolved, which is in this case improving the security management of information technologies.

- The critical reference group (CRG): those for whom the research is being carried out and who also participate in the research. This consists of the Sicaman Nuevas Tecnologías S.L. company, its customers and the participants in the research projects.

- The fourth participant—the beneficiary, which consists of those organizations that may benefit from the results of the work, i.e. all those small and medium-sized companies that might wish to apply advanced information security management methods to their information systems in order to improve the security of their information technology products and processes in a controlled and methodical manner. The results obtained after carting out this research will improve the efficiency of the installation and maintenance processes of information security management systems. The principal beneficiaries will therefore be all those companies that are linked to the critical reference group.

The stages identified in order to demonstrate the cyclical nature of action research have been applied in this research as follows:

- Planning: Once the problem related to incorporation of security management systems into SMEs had been identified, we planned the development of a methodology that would allow the creation of an ISMS with the minimum possible number of resources, which would be adapted to the size and maturity of the company.

- Action: having defined the principal elements involved in the ISMS-creation process, we then went on to create a model and to apply it in determined case studies. The elements that would be used to construct the final ISMS were also applied in the case study.

- Observation: Once the elements had been applied and the ISMS had been created, the results obtained were evaluated. This allowed us to improve the original proposals and to eventually define a methodology that would systemize the creation and evolution of an ISMS for a company, along with a model that would permit its validation. The entire method is supported by a prototype that allows the simple generation of ISMSs and the work to be carried out with them in order to analyze their evolution over time.

- Reflexion: the cyclical nature of the action research method was borne in mind, and results that were the product of successive iterations were therefore obtained. The research team has shared and contrasted these results in the national and international forums of scientific communities related to the topics being dealt with in this research.

A schema of the participants and the cycles resulting from the application of the action research method in this research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Application of Action Research (AR) during research.

In summary, the results obtained after applying the method were:

- A suitable method with which to manage security and its level of maturity in SMEs’ information systems.

- A security maturity and management model based on the methodology developed and denominated as the base schema, which is appropriate for the resources of SMEs. The result was accepted by the critical reference group.

- Benefits for the participants: scientific benefits for the researcher and practical benefits for the beneficiaries.

- The knowledge obtained can be applied immediately.

The research has been developed in a typically cyclical and iterative process, combining theory and practice.

2.2. Researches about the Security Culture

In order to analyze the solutions proposed by other researchers so as to resolve the problem detected as regards the lack of a security culture in SMEs, we carried out a short literature review on this topic, which enabled us to select 12 research works. These were considered to have the closest relationship with our analysis, whose eventual objective was to create a framework for the security culture in SMEs and its problems.

Of the proposals analyzed, the ones that provided most details were those by Dojkovski and Sneza, since they were the frameworks most similar to the MARISMA methodological framework and because they contained elements of interest for the completion of that framework, such as aspects of e-learning and learning in the case of Dojkovski and those of external influences and behavior in that of Sneza. These two pieces of research were also those that presented the most complete security culture frameworks. The majority of research into the information security culture [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] stresses that a cooperative culture that includes an information security culture is a collective phenomenon of a transcendental nature and can be designed by an organization’s management. Nosworthy [33] places special emphasis on the fact that the organizational culture plays an important role in information security, since it allows the organization to resist the changes undergone by its system. Although the majority of research coincides as regards the importance of the security culture for ISMSs [33], there is not as yet a clear definition of the concept of ‘security culture’ [37], and several viewpoints exist:

- Siponen [38] states that “the consciousness of information security” is a state in which an organization’s users are conscious of their mission as regards security, and this is divided into two categories: (i) the application framework (standardization, certification and institutionalization activities), and (ii) content (the human aspect).

- Von Solms and Vroom [39,40], meanwhile, suggest the establishment of a training culture and cooperation with employees on the basis of the gradual adoption of the organization’s security management, individual values and user behavior.

- Dhillon [6] has a broad view of the term ”security culture”, and defines it as the behavior of an organization’s users that contributes towards the protection of data, information and knowledge.

- Eloff [31] defines the information security culture as a set of information security characteristics, such as integrity and the availability of information.

- For Chia [41], the information security culture is a fundamental aspect, and this author defines a set of dimensions that are important as regards measuring the efficiency of the information security culture: (i) a belief in the importance of information security; (ii) a long and short-term balance, goals, policies, procedures and continual improvement processes; (iii) cooperation and collaboration; and (iv) attention to auditing objectives and their fulfillment. This list has, however, recently been criticized by Helokunnas [42], who places particular emphasis on the human aspects of information security.

- Straub [43] maintains that with information systems it is always assumed that a person belongs to a single culture, and this author therefore proposes using the theory of social identity as a basis for research into the information security culture. The idea behind the social identity culture is that each individual is influenced by a multitude of cultures. According to [43], upon applying the social identity culture, users will be influenced by ethical aspects, each country’s legislation and the organization of security. This culture has an effect on the way in which the individual interprets the significance and importance of information security.

- Kuusisto [44] proposes a system in which the security culture is created on the basis of the interaction between the reference framework and its components.

- Finally, Detert [45] considers the security culture to be a key aspect of ISMSs, and has developed a general framework for information security which is based on eight dimensions [37] applied these eight dimension to the areas of information security and identified the principal factors of information security in each dimension.

Although recent studies demonstrate SMEs’ concern about the difficulties involved in developing an information security culture [46], the fact is that the security culture has a series of additional problems as regards its implementation in SMEs [47]. According to [48,49], SMEs are, when compared to large organizations, particularly prejudiced against seeking an information security culture. This is for various reasons:

- SMEs lack the funds, time and knowledge needed to coordinate information security or to impose an information security culture in an efficient manner [10,50].

- SMEs do not tend to have procedural policies at their disposal, nor do they tend to define the responsibilities of their information systems’ users [51].

- When compared to large companies, SMEs are more susceptible to national influences, such as changes in legislation [52].

In conclusion, we can highlight that several security management frameworks for the development of an information security culture have been developed [11,17,31,34,40,42,53,54,55], but they tend to be oriented towards large organizations. According to Hutchinson and Dojkovski [48,56], however, the frameworks for SMEs should be based on the study of their real needs so as to identify and develop a framework specifically intended for them.

Experts have proposed various conceptual frameworks that will permit information security management to include the information security culture, and these are based on policy management, the raising of awareness, training and education initiatives [57,58]. These frameworks may, however, be more appropriate for medium-sized and large companies owing to the resources needed. Various frameworks for the establishment of the security culture have appeared over the last few years, and are based on: organizational culture and the measurement of the information security culture [11,32]; shared values [51]: information security phases, levels of maturity [17]; measures related to the development of the individual, group or organization that will permit the discovery of their lacks as regards security [31]; the socio-technological level of information security [59]; measures based on the users’ morals and ethics [38]; informal awareness-raising methods [40]; key concepts of the organizational culture [34]; the personnel’s capabilities [54]; organizational learning [55]; and a multi-faceted approach [41]. Despite their obvious value, these frameworks focus on fragments of the theoretical field, without being integrated into a common and complete framework. What is more, they do not tackle the particular requirements of SMEs.

Kuusisto and Ilvonen [44] therefore reach the conclusion that there is no suitable regulation for security management in SMEs, and that there is principally a need for models that are valid and that will allow the security culture to be increased in SMEs.

Two proposals focused on analyzing the need for a security culture in SMEs are shown in the following sub-sections.

2.2.1. Proposal of Dojkovski

Dojkovski [48] proposes the construction of an ISMS that is oriented towards SMEs and whose central point is the security culture. This is done by analyzing the state of SMEs in Australia, after which the conclusion is reached that that the information security risks for Australian SMEs have increased over the last 15 years as the result of greater access to the Internet, but that the level of information security and awareness in SMEs has not maintained a good rhythm and continues to be low.

This proposal does not enter into the mechanisms by which the ISMS can be employed, nor does it mention aspects such as the controls, metrics and risk management that it should contain, but rather focuses solely on the elements that a security culture ISMS should contain.

The principal causes of the security management problems detected in the SMEs were:

- SMEs view the information system as a system that supports the company’s production departments and not as something that is vital for their business. This makes them reactive rather than proactive to security failures.

- For SMEs, cost is fundamental, and they view security as an unjustified expense.

- The managers are not concerned about security and neither, therefore, are the other employees.

- Users find it very difficult to fulfill this framework. What is more, it is very difficult to change the bad habits acquired, and none of the users wish to be responsible for the information security system assets.

- Initiatives should be appropriately managed, and the policies and procedures should be presented to users when they sign their contracts. This may be more difficult for SMEs, since they lack formal organizational structures. It is also important to consider the fulfillment of security within the evaluation of the employees’ work.

- The lack of appropriate information as regards security. Those surveyed considered e-learning to be a valid work tool with which to improve the level of the information security culture, as was the possibility of being able to share experiences with other SMEs. The problem is, however, that it is not normally possible for the workers at SMEs to go on courses for reasons of time and money, and many workers do not take these courses if there is no motivation for them to do so.

Dojkovski [48] proposed that these problems should be dealt with by constructing an ISMS that was oriented towards the development of an information systems security culture, and which should consider how people think and behave, thus suggesting the need for an interpretative research approach. The model was validated in four groups, following the Lichtenstein [60] principles. Several frameworks and approaches were used to develop a valid theory, after which a set of SMEs were analyzed with the intention of determining their security consciousness, the challenges confronted by SMEs as regards fomenting an information security culture and the viability of the pre-project.

This framework is formed of the following elements:

- Organizational and individual learning: The information security culture should be disseminated throughout all levels of the organization at both an individual and a collective level [31]. According to Van Niekerk [55], it might be useful to employ an organizational learning approach.

- E-Learning (cooperation, collaboration and the exchange of knowledge): SMEs could undertake electronic learning (e-learning) [61], and could also cooperate and collaborate electronically in information system security communities and forums [42] with the objective of improving the information system users’ security culture.

- Management: Awareness-raising programmes (supported by the management, threats of disciplinary measures, clauses in employment contracts, etc.), training, education or the value of leadership [62] are valuable initiatives for the development of the information security culture [12,54]. It is probable that different levels of awareness raising, training and educational needs are generated for the individual employees in SMEs.

- Security culture: Procedures with which to respond to new events (such as security violations) will help to underline the importance of information security for workers [27]. Incentives may also be useful as regards modifying employees’ behavior. However, Rosanas and Velilla [14] warn that management controls should be based on ethical values.

- Behavior: The management of initiatives whose intention is to develop desirable behavioral features with regard to the personnel’s responsibility, integrity, trust and ethics [20]. Strong values are, however, necessary to support management initiatives [14]. Information security is strengthened when strong values are disseminated among collaborating entities and other interested parties [42]. The development of intrinsic motivation is important [38], and can be supported by promoting those personnel who appropriately fulfil the security regulations [45].

- National ethics and organizational culture: According to Helokunnas [42], the creation of security forums at a national level may favor the creation of an information security culture.

According to the research carried out by Dojkovski [48], the principal challenges as regards developing the information security culture in SMEs include:

- Motivating company owners to allocate appropriate funding to information security.

- Convincing company owners to carry out a formal risk analysis.

- Ensuring that company owners develop information security policies and procedures and assign responsibilities.

- Developing a proactive attitude towards information security.

- Identifying and establishing a series of awareness-raising activities that can be adapted to SME environments.

The principal conclusions reached after applying the framework were that, although it valuable on an individual basis as regards identifying the elements that an SME and security culture-oriented ISMS should contain, it is not a complete and usable model.

2.2.2. Proposal of Sneza

This author proposes the construction of an ISMS whose core is the development of the information security culture, whilst bearing in mind how people think and behave [63]. The framework for the security culture is therefore established on the basis of qualitative rather than quantitative aspects. The framework was defined by carrying out a study on Australian SMEs with less than 20 employees [64].

This framework describes three external influences:

- National ethics and organizational culture. A nation’s culture may affect the organization of information security. Social ethics may also have an important impact. Helokunnas [51] states the importance of social networks as regards sharing problems related to information security and creating a consciousness about the subject.

- Government initiatives: governments could play a fundamental role in the creation of an information security culture by approving special legislation and providing support (courses, subsidies, etc.).

- Suppliers: suppliers could ensure that SMEs are reliable in the form of the additional guarantee of the security of the products they sell them.

This framework is composed of the following elements:

- Leadership and corporative government: The owners of SMEs should demonstrate that they support information security management. According to Dutta [62], the management’s support is highly valued by large companies, but this is not the case at SMEs.

- Organizational culture: An organization’s culture and environment have a direct influence on the fulfilment of security management.

- Management: Firstly, SMEs consider the results of risk analyses to be a key aspect as regards guaranteeing that policies and procedures are really necessary. Secondly, SMEs must be guided by the risk of losing assets, which they discover via the risk analysis. Martins identified this need in large organizations. Thirdly, it is necessary to allocate a budget to security management, whose resources should include the initiatives needed to establish a security management culture. Martins also suggested that the budget has a great influence on organizations. Fourthly, the procedures used to respond to information security incidents would help to underline the importance of information security for the employees, and this has also been generally suggested by the OCDE [27]. Fifthly, SMEs should receive some kind of reward for periodically evaluating their information security culture. In addition, finally, the employment contract should include sanctions or incentives with which to motivate employees. All management processes should be evaluated periodically.

- Individual and organizational learning: e-learning, training and education are potentially valuable initiatives for the development of the information security culture for both SMEs and large companies [38,54,61]. The exchange of knowledge, cooperation and collaboration are important for learning at the different levels of the organization when the objective is to develop the information security culture. The learning processes should be evaluated periodically.

- Raising awareness about the organization’s security: [61] suggested formal and informal awareness-raising measures for SMEs, while [38] proposed the inclusion of awareness-raising measures that additionally contained aspects of persuasion.

- Reviews and evaluation: SMEs should periodically examine and evaluate the measures adopted in order to continuously improve.

- Behavior: A series of external and internal initiatives could be used in an attempt to develop behavior regarding responsibility, integrity, trust and ethics. According to Dhillon [20], in large organizations this transformation originates from internal management initiatives, whilst in the framework proposed [63] this responsibility is shared by internal and external agents. Siponen [38] states the importance of intrinsic motivation. One efficient measure for an organization is that of providing those users who comply with information security regulations with benefits [45].

The principal conclusions reached after applying this framework were:

- The owners of Australian SMEs lack an appropriate understanding of the importance of information security in their businesses [23,50,51,65].

- It is necessary to persuade SME owners to undertake a formal scenario based on risk analysis and the protection of information assets. Recent information security findings have shown a strong correlation between the formal risk evaluation process and spending on information security [23].

- Australian SME owners do not understand the strategic value of IT in their businesses. Other studies have demonstrated that this is not an isolated case, and a study by O’Halloran [66] therefore demonstrated that SMEs in the United Kingdom do not understand how security provides their businesses with added value.

- A previous requirement for the development of the information security culture in SMEs is the development and communication of policies, procedures and responsibilities. As many experts and studies have pointed out, the majority of SMEs in developed countries lack policies of this nature [23,50,65].

- Cooperation, collaboration, knowledge exchange and electronic learning were valuable activities for Australian SME employees. This finding coincides with that of the study carried out by ISBS [23].

Although experts have indicated the importance of users’ values regarding the management of security at organizations, regardless of their size, [11,31,51,67], the study carried out by Sneza [63] demonstrates that instilling these values in users at SMEs is a highly complex process.

Some of the limitations of the study were: (i) the analysis is interpretative and the conclusions are based on the study of a small set of Australian SMEs; (ii) the framework of the process lacks elements that are solely applicable to SMEs; (iii) the framework of the process lacks the detailed guidelines that would permit its application; (iv) the study is focused on researching SMEs with a technical profile whose employees already have technical knowledge; (v) the framework is developed by concentrating solely on the context of Australia and is not therefore valid for other countries; (vi) the framework does not provide companies with proactiveness and all the responsibility of being dynamic is left up to them.

2.3. Conclusions

The analysis of 12 research works on security culture was used as a basis to obtain a group of meaningful characteristics for the implementation of these processes. A comparative analysis between these pieces of research was also carried out. Each of the characteristics is described in the following section.

- Group 1. Characteristics oriented towards the application of framework regulations.

- ○

- Standardization: The implementation of the process will be based on the regulations related to the management of information security systems.

- ○

- Certification: This process will permit users to obtain any type of temporary certification.

- ○

- Measurement: This system will make it possible to measure the company’s level of security culture.

- ○

- Cultures: This system not only takes into account the internal cultural aspects, but also local, sectorial and international legislation.

- Group 2. Characteristics focused on users’ human aspects.

- ○

- Progressive adaptation: The process will permit the users’ security culture to be adapted in a progressive manner.

- ○

- Theoretical Approach: The process will be based on an appropriate theoretical and regulative approach.

- ○

- Practical Approach: The process will be oriented towards a practical application as regards users.

- ○

- Critical Aspects: The human aspect will be considered critical in the preparation process.

- ○

- Psychological Factors: Disciplinary actions, clauses, rewards for points, etc. and their effects on the users’ psychology when using the process will be taken into consideration.

- Group 3. Other desirable aspects for the process.

- ○

- Oriented towards SMEs: It must have an orientation if it is to be valid for both big companies and SMEs.

- ○

- Low cost resources: It should be oriented towards low costs as regards the implementation and maintenance of the system

- ○

- Core of the ISMS: The security culture process is the main process in information security management. (ISMS)

- ○

- Dynamic Knowledge Base: This process is able to learn from the security incidents and change those weaknesses into strengths by incorporating the incidents into the knowledge base in order to reinforce the security culture of those aspects.

As will be observed in Table 1, the core of each of the proposals is one or several of these characteristics. The security culture process of MARISMA has been created in order to provide a solution to these characteristics, but without it being at the core of ISMS.

Table 1.

Comparative between researches about the security culture.

3. MARISMA Framework

The methodology developed for security management and its maturity in SMEs will allow any organization to manage, evaluate and measure the security of it information systems, but is principally oriented towards SMEs, since they are those with the highest rate of failure as regards the use of existing security management methodologies [68,69].

One of the objectives pursued by the MARISMA methodology is that it should be easy to apply, and that the model developed on it will permit a greater level of automation and reusability with a minimum amount of information that has been obtained in a very short amount of time [70]. Speed and cost reduction have been prioritized in the methodology, thus sacrificing the precision provided by other methodologies, i.e. the objective of the methodology developed is to generate one of the best security configurations, but not necessarily the optimum one. Priority is instead given to time and cost saving rather than precision, whilst still guaranteeing that the results obtained will be of sufficient quality [71], since they will be supported by other regulations [72,73].

Another of the main contributions of this methodology is a set of matrices that allow the various components of the ISMS to be related (controls, assets, threats, vulnerabilities, risk criteria, procedures, registers, staff, technical instructions, regulations and metrics). The model will use these matrices to automatically generate the majority of the information needed, thus considerably reducing the time needed for the development and introduction of the ISMS [74]. This set of interrelations among all the components of the ISMS is designed in such a way that if any of these objects is changed, the measurement value of the remaining objects in the model will be altered, such that it will always be possible to obtain an updated evaluation of how the company’s security system is evolving.

The information obtained after testing it at various companies has therefore allowed us to develop a security management and maturity methodology for information security systems, along with its associated model (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sub-processes of the methodology MARISMA.

This methodology has three main sub-processes:

- SMScG—Security Management Schema Generation: The principal objective of this sub-process is to construct the ‘schemas’, which are the structures needed to build ISMSs, and are created for a possible set of companies in the same category. These schemas are reusable and permit a reduction in both the time needed to create the ISMS and its maintenance costs so as to make them suitable for the dimension of an SME [68]. The use of schemas is of particular interest in the case of SMEs since their special characteristics signify that they tend to have simple information systems that are very similar to each other.

- SMSyG—Security Management System Generation: The main objective of this is the use of an already-existing schema to create an ISMS that will be suitable for a company.

- SMSyM—Security Management System Maintenance: The principal objective of this sub-process is to maintain and manage the security of the company’s information system, contributing information that is updated over time to the ISMS generated.

The principal activities used to create a progressive security culture are focused on the ISMS maintenance process.

4. SME-SCCM: Security Culture Certificate Management

One of the principal processes in MARISMA is that focused on creating a security culture and ensuring that those users who will have to work with the company’s information system progressively adopt it, otherwise they will not be able to access that system [75].

Several methods by which to establish a security culture in SMEs were tested during the development of our research. We eventually opted for a procedure consisting of the use of a series of security-related questionnaires associated with the regulations of the ISMS, with the objective of maintaining and improving the company’s security culture without incurring high maintenance costs.

The main idea is that the users of the information system will not be able to use that system unless they have obtained a ‘certificate of cultural level’, which can be withdrawn and which will be renewed periodically in order to guarantee that the necessary level of the security culture continues to be maintained.

The simplicity of this activity, coupled with the short amount of time required, allows it to progressively create a security culture in users. Its automation signifies that additional maintenance and planning costs can be avoided, and ensures that the security culture remains inherent to the information system itself.

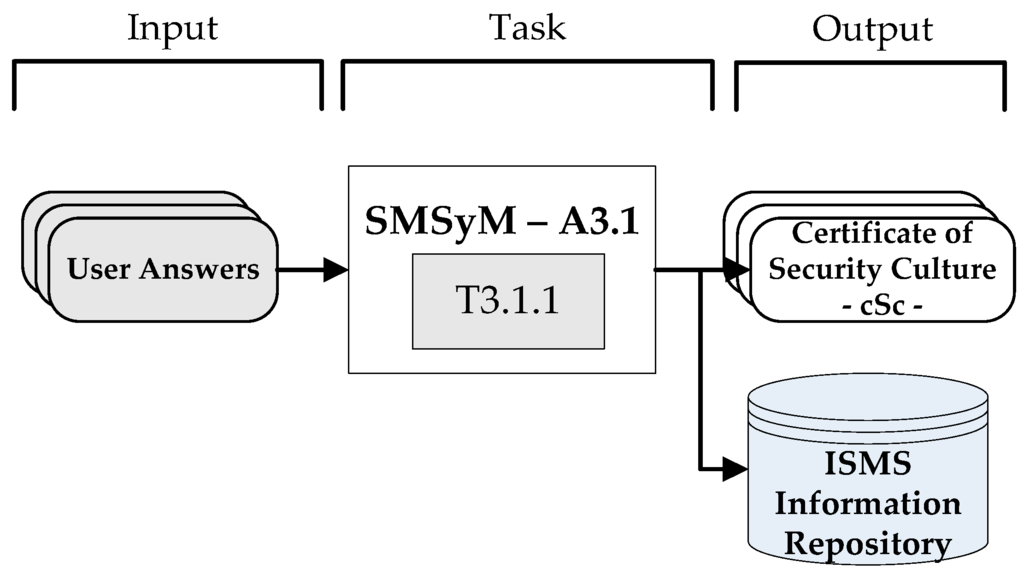

The basic schema of the inputs, tasks and outputs of which this activity is composed are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simplified schema of the task in Activity A3.1.

- Inputs: the inputs are the users’ responses to the questionnaire as regards the regulations generated by the system.

- Tasks: the sub-process will be formed of one single task—that of issuing the security certificates.

- Outputs: The output produced by this sub-process will consist of the security culture certificate, which will be issued only if the mark obtained in the questionnaire is five or above, otherwise the certificate will be denied. Those users who fail the test are advised to either study the ISMS security manual or attend a security management course in order to increase their knowledge of the material.

Figure 4 shows the activity task in much greater detail, and it is possible to see how the task interacts with the ISMS information repository, which is in charge of containing the security certificates issued and the marks obtained.

Figure 4.

Detailed schema of the task in Activity A3.1.

The objective of Task T.3.1.1 is to carry out an evaluation of the knowledge of those users who wish to access the company’s information system as regards the regulations of which the ISMS is composed, in order to determine whether or not they are sufficiently prepared to access it.

Users access shall be limited to the Information system until they can obtain the card point. This ensures that users have a basic understanding of the security policies before access to the system. This control helps to mitigate the risks to which it is subjected the system, forcing users to increase their security culture gradually and at a low cost to the Company.

Any users who fail the test must study the information on the ISMS again or attend a security management course in order to acquire the level of knowledge needed to access the system.

There are two different processes in this task: (i) obtaining a security culture certificate; and (ii) Renewing the security culture certificate.

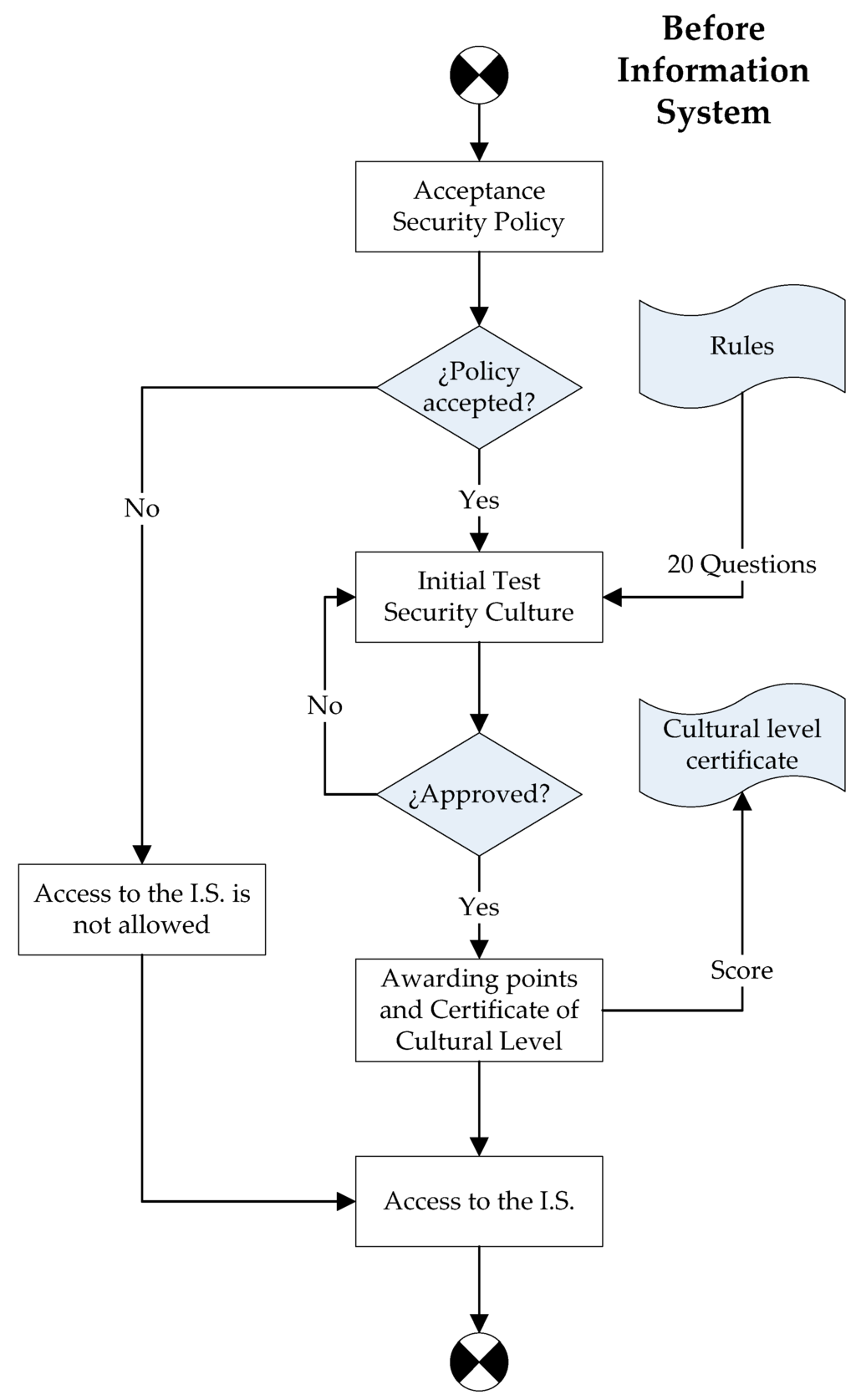

Figure 5 shows a detailed diagram of the flow of the different steps of which the first of these processes (obtaining a security culture certificate) is composed. The first time that the user accesses the information system, s/he must accept the company’s security policy. This guarantees that s/he reads, albeit rapidly, the company’s policy (thus improving his/her security culture). The user must then pass an initial test composed of twenty questions taken randomly from the company’s ISMS.

Figure 5.

How a “security culture” certificate is initially obtained.

Unless the user is able to answer 50% or more of the questions in the test correctly, his/her level of knowledge regarding the company’s information system security culture will be deemed inadequate, and it will be necessary to continue taking tests until a mark of five or more has been obtained. The user will not be able to access the company’s information system until s/he attains a sufficient level of “Security Culture”. This therefore guarantees that the culture is introduced efficiently.

Once the user has managed to pass the test, his/her mark is saved in a register, a “Security Culture” certificate is issued and access to the information system is granted. The mark obtained will be important as regards maintaining the certificate over time, since it will be modified by other tasks in the system.

During the research carried out at SMEs, which were Sicaman’s customers, it was decided that the ideal number of questions should be between 20 and 30. A lower number makes the results less valuable while a higher number makes those users that must take that test feel dissatisfied and uncomfortable.

The questions are chosen from a knowledge base, which has a group of questions that are pre-established on the basis of the regulation pattern/schema chosen (e.g., they are based on ISO27001). This knowledge base is complemented with questions excerpted from the company’s security policy, which all users must know and comply with.

The second process of which the ”take the security culture test” task is composed is that of renewing the security culture (SC) certificate, either because it is out of date or owing to the loss of qualification points. The steps involved in this process are detailed in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schema for SC certificate renewal.

The renewal period for the security culture certificate has been set at 1 year, although this time period can be reduced to 6 months if it is deemed necessary to speed up the establishment of the information security culture. The simplicity of the procedure signifies that it is not advisable to let more time lapse before the certificate is renewed, as the security culture may decrease (i.e., a time period of 2 years would be counterproductive) or to make it more frequent as this may lead users to reject it (i.e., a time period of less than six months may cause the users to reject the culture). Figure 7 shows that, according to the investigations carried out during the development of this research, if the renewal time is imposed as being between 6 and 18 months, the level of the security culture (LSC), which is measured as the average mark obtained in the tests that must be passed to obtain the certificate, is higher. It is, therefore, recommendable to renew the certificate every 12 months.

Figure 7.

Association between the LSC and the certificate renewal period.

In order to avoid interfering with the users’ daily work, the notification stating that the certificate needs to be renewed is issued 1 month before its expiry data, thus allowing the user to take the test at the time that best suits him/her during that period. The system reminds users of this on a daily basis. If the user has not taken and passed the test by the time the expiry date is reached, his/her access to the system will be blocked until the certificate has been renewed.

Given that the time taken up with resources (TtR) is one of the principal success factors of the methodology (particularly in the case of SMEs), we have estimated how long it would take to establish the security culture and have reached the conclusion that the simplicity of the process makes it totally acceptable for SMEs (it has been estimated that the time need to initially obtain the certificate is between 1 and 2 h—around 90 min to read the security policy and understand the elements of the ISMS, and about 30 min to take the test). This investment of time is only necessary initially since, although the certificate must be renewed periodically, it is only necessary to read the security policy and pass the test the first time. The experience gained in the test cases show that information system users consider this amount of time to be acceptable.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that any users who attempt to skip reading the security policy in order to save time will have to repeat the test various times, and will eventually spend just as long as they would have done if they had read the policy. Either path is considered correct, since both lead to the objective of planting the initial seed of the ‘security culture’ in the user.

This simple task means that users never lose sight of the importance of keeping the level of their security culture updated. Given that the test is carried out randomly by means of a combination of questions as to the security activity regulations at the company, the users’ consciousness of these regulations increases more each time, in an intuitive manner and at minimum costs.

Furthermore, the marks on the security culture certificates change when certain actions take place: (i) violations of security regulations, and (ii) the loss of the certificate for having less than the required number of points.

While carrying out this research it was determined that the larger the company’s security culture, the greater the number of reports of security violations made by users, particularly when these reports do not actually imply serious sanctions against those reported.

When a security incident is reported and the person responsible for security considers that it is justified and therefore approves it, this affects not only the company’s global security level but also the marks on the security certificate belonging to the user who has perpetrated the security violation. Each violation implies the loss of one point on the security culture certificate (SCC) that the user has at that moment, which were obtained after taking the security culture test, minus any points that had already been lost during the period in which the certificate is valid for violations of the company’s regulations. If the loss of points owing to security violations leads the points on the certificate to fall below five, the user is deprived of the certificate and his/her access to the company’s information system until s/he has again passed the test and therefore obtained another security certificate. This process is shown in its entirety in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Alteration of Level Security Culture (LSC) owing to a violation of the regulations.

This process serves as a preventative control to make the system users conscious that system violations come at a price, although the measure is not excessively serious and the users do not therefore reject it. This control does not have a representative management cost for the company as regards either time or money, but does suppose an important reinforcement in that it establishes a correct security culture in the company.

Figure 9 shows the relationship between the marks obtained in the security culture test and the regulation-control matrix, such that when a security certificate is obtained with low marks, this affects the controls associated with the regulations from which the questions were obtained, since failure to correctly answer a question in the test reduces the level of controls associated with that question to a percentage (−0.1%). Similarly, if the question is answered correctly, the level of the controls rises (+0.1%).

Figure 9.

Managing the security culture certificates.

The process described has various advantages over its predecessors, in addition to containing more innovative proposals. It provides solutions to most of the characteristics identified in the last paragraph. According to this research, it should fulfill the security culture processes that are implemented in companies.

An analysis of how the SME-SCCM of MARISMA resolves each of these necessities or characteristics is summarized as follows:

- Group 1. Characteristics oriented towards the application of the regulation framework.

- ○

- Normalization: The development process is based on the use of reusable patterns. The use cases were created with patterns regarding the ISO27001.

- ○

- Certification: The process developed permits the users to obtain a security points card, which enables them to access the system and provides an indication of the level they have.

- ○

- Measurement: The system makes it possible to measure the company’s level of security culture, at user, department and company levels.

- ○

- Culture: The process developed takes multicultural aspects into account, which merely have to be added to the corresponding pattern.

- Group 2. Characteristics oriented towards the users’ human aspect.

- ○

- Progressive adaptation: The process permits the users’ security culture to be adapted in a progressive manner because it lets them know their real level of security culture at all times. This is achieved through the use of the points card. It is possible for them to take the test again to obtain higher marks.

- ○

- Theoretical Approach: The process is based on the theoretical approach and appropriate regulations. In this case, the pattern used is based on the ISO27001 international standard.

- ○

- Practical Approach: The process is oriented towards being applied by users in a practical manner because it ensures that they are continuously conscious of their limits and can compare themselves with their colleagues.

- ○

- Critical Aspect: The human aspect has been considered critical when developing the process and is at its core.

- ○

- Psychological Factors: The points card works as a psychological measure that pressurises the users to improve and to be careful not to incur sanctions, since these are also seen by their superiors. Various kinds of disciplinary action had been taken before the implementation of the points card, none of which worked.

- Group 3. Other desirable aspects.

- ○

- Oriented towards SMEs: Its validity for SMEs was borne in mind, and it has principally been validated at this type of companies.

- ○

- Low cost resources: The implementation and maintenance costs are very low because of the simplicity of the process. More complex systems were tested but they did not work.

- ○

- Core of the ISMS: SME-SCCM has not been considered to be the core of the MARISMA methodology, although it is a very important process.

- ○

- Dynamic Knowledge Base: This process is able to learn from security incidents because the event module generates knowledge for the question base of the pattern selected. The tests are therefore generated in an intelligent manner, with priority being given to those questions that relate to greater vulnerabilities in the system.

It is, therefore, possible to conclude that this activity allows users to obtain a security culture certificate in a simple manner, whilst making it easy for them to increase their knowledge of the ISMS and evaluating their level of knowledge of that ISMS. The security culture certificate is simultaneously updated in a dynamic manner via the application of sanctions for security violations, which allows its updating to take place dynamically and at no cost.

5. Practical Application of MARISMA

With regard to the level of application, the principal aspect of the security culture will be the use of questionnaires with the objective of determining whether the company’s information system users have sufficient knowledge to be able to fulfill and respect its regulations. The result will be a qualification regarding the users’ security culture, obtained by means of a test automatically generated by the security culture system (Figure 10) associated with the ISMS. This area corresponds with Activity A3.1 of the methodology’s Security Management System Maintenance (SMSyM) sub-process.

Figure 10.

A3.1—Screenshot of the security culture test.

When the security culture certificate is revoked for reiterated security violations, or it expires, it should be renewed by following the same process described in the previous section.

Table 2 shows a simulation of a test taken by a system user in order to obtain access to that system.

Table 2.

Test used to obtain security culture certificate.

Once the test has finished, the system analyses the result obtained in order to determine whether or not the test should be repeated. Those users who pass obtain their certificate for the stipulated amount of time, and this certificate gives them access to the information system (Table 3).

Table 3.

Result of security certificate test.

If, however, the security of one of the ISMS regulations is violated, the security culture certificate will be affected, and 1 point per sanction will be removed. To continue with the case used as an example, the next step in the process is therefore to remove a sanction point from the reported user’s certificate. Since he had 6.5 points before the sanction, he will now have 5.5 points. If the user’s marks fall below 5 points, the system will revoke his permission to access the company’s information system and will oblige him to obtain a new security culture certificate.

Finally, when the user takes the test, the correctly answered questions will slightly increase (+0.1%) and those answered incorrectly will slightly decease (−0.1%) the controls associated with the regulations and procedures of which the questions in the test are made up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Example of penalization of controls for security culture.

This system was developed and modified over various years. The method used was “Action Research”. The final process version (presented in this paper) was validated at ten SMEs principally related to Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and new technologies and a workforce of between 10 and 50 people. It was tested for a year with three tests (at the beginning, after six months and at the end of the year). The pattern used was based on the ISO27001 standard and was the same for all the companies.

The conclusions reached were:

- There was a progressive increase in the security culture of all ten companies of between 12% and 15%, between the first and last tests. No company’s level of security culture worsened.

- The level of security incidents at the companies was reduced by between 5% and 12% between the first and last tests. It is important to highlight that some companies took additional decisions that enabled these results to increase. The level of incidents did not increase at any if the companies.

Throughout the entire research process, it was noted that 3 of the 10 SMEs stopped maintaining the ISMS because they considered it to be expensive or inefficient (30%). A fourth company stated that it would continue with the process in the short term, but was thinking of discontinuing its use in the medium term. After the process had been completed at these 10 SMEs, only two of them (20%) decided not to continue using it, while one stated that it might have difficulties in doing so in the medium term. The reason for this was not, however, directly related to the security culture process itself, but rather to other ISMS processes.

6. Conclusions

This paper shows the importance of the security culture in the ISMSs of SMEs, how this element has been incorporated into the MARISMA methodology and its advantages.

The MARISMA methodology complies with the principles which, according to the OCDE [27], all ISMS installation and maintenance methodologies should follow in order to attain a correct information security culture, thus guaranteeing the success of the ISMS in the company. These principles and how the MARISMA methodology complies with all of them, thus demonstrating its validity, are shown below:

- Awareness raising, responsibility, response, ethics: A system of courses based on simple test-type questions and a system of rewards and sanctions is used to progressively create consciousness of the security culture in information system users. Activity A3.1 is based on simple questionnaires.

- Democracy: The system should protect the company and its users’ jobs, as long as this does not suppose any impediment towards them carrying out their work efficiently. The principal objective of Activity A3.1 is to permit access only to those users who are conscious of the importance of security in the information system.

- Risk Evaluation: The system should be capable of continuously self-evaluating its risks and of providing measures to deal with them. The document obtained in Activity A3.1 (the security culture certificate) provides constancy of the level of knowledge that users have attained as regards regulations, and this measure is completed with the risk evaluation and the improvement plan in Activity A2.3 (Risk analysis).

- Design and realization of security: The methodology is intended to be integrated into the framework as another piece of it, and is oriented towards organizing the means used to work as regards security without being a burden for the workers. Activity A3.1 is totally integrated into daily work with the ISMS, and is simply one more activity.

- Security management: The methodology should allow security to be managed in a way that is comfortable such that the security culture with which it is associated can be introduced into the information system users naturally. The entire MARISMA methodology is focused on simplicity when working with it.

- Re-evaluation: The methodology should have metrics that permit the system to be able to periodically re-evaluate itself at a low cost, and to recommend suitable metrics. The MARISMA methodology has both general and specific characteristics that allow the security scoreboard to be kept updated at all times at a low cost, which makes it possible to know the level of fulfillment of the security controls at all times. One example of these metrics is each user’s security culture certificate, which defines a minimum security culture level for the system users.

The SMEs that participated in this research highlighted four advantages that contribute to the development process of the “Security Culture”. These were:

- Simplicity: It is a practical method to apply and its users do not reject it. Some of the companies that participated in this research have included an automated process in their intranet, such that if a user does not have the security card or if it is lost, access to the company’s intranet will be blocked until the answer to the question is correct, and the certificate is once again awarded. The convenience of the method signifies that the users do not see it as an obstacle in their job, and they therefore understand its objective.

- Quantitative value: This method permits the company to attain a quantitative figure of the level of its security culture, which can be compared with different time periods. This is of great value for the companies because it lets them know whether the decisions they are making are appropriate.

- Low cost: The implementation of the process implies very low costs for the companies. They do not require a great investment from others. (e.g., Consultants). It does not consume resources, even as regards its maintenance.

- Learning: The constant capacity to improve the knowledge base on the basis of the security events that make it possible to reinforce the users’ knowledge of security in the weaker aspects of the company.

The characteristics provided by the new methodology and its orientation towards SMEs have been very well received, and its application is proving to be very positive since it allows this type of companies to access information security management systems, something which has until now been limited to large companies. The methodology also allows short-term results to be obtained and reduces the costs associated with the use of other methodologies, thus leading the company to feel greater satisfaction.

All future improvements to the security culture will be oriented towards reducing information system users’ non-fulfillment of security management, whilst always respecting the principal of the cost of resources and being oriented towards the security culture.

Acknowledgments

This research has been partially co-funded by the ERABAC (1315ITA227) and ESACC (1315ITA225) projects, financed by the “D.G. de Empresas, Competitividad e Internacionalización de la Consejería de Economía, Empresas y Empleo de la JCCM”, the SIGMA-CC (TIN2012-36904) and GEODAS (TIN2012-37493-C03-01) projects, financed by the “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional FEDER (European Regional Development Fund)” (Spain), the SERENIDAD (PEII14-2014-045-P) Project, financed by the “Consejería de Educación, Ciencia y Cultura de la Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-la Mancha and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional FEDER (European Regional Development Fund)” (Spain), the “Plataformas Computacionales de Entrenamiento, Experimentación, Gestión y Mitigación de Ataques a la Ciberseguridad Project—Code: ESPE-2015-PIC-019”, financed by the ESPE and CEDIA (Ecuador), and the PROMETEO project, financed by the Ecuadorean government’s Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (SENESCYT).

Author Contributions

Luis Enrique Sánchez and Antonio Santos-Olmo have contributed to the design, development and validation of the research in the private sector. Ismael Caballero and Eduardo Fernández-Medina has contributed to the design, development and validation of research from the aspects of University. Sara Camacho has contributed reviewed the proposal from the point of view of international validation and teaching innovation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Santos-Olmo, A.; Sánchez, L.E.; Ismael, C.; Camacho, S.; Daniel, M.; Fernández-Medina, E. Importancia de la Cultura de la Seguridad en las PYMES para la correcta Gestión de la Seguridad de sus Activos. In Proceedings of the VIII Congreso Iberoamericano de Seguridad Informática (CIBSI15), Quito, Ecuador, 10–12 November 2015; pp. 14–27. (In Spanish)

- Whitman, M.; Mattord, H. Principles of Information Security; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Disterer, G. ISO/IEC 27000, 27001 and 27002 for information security management. J. Inf. Secur. 2013, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, K.; Faßbender, S.; Heisel, M.; Küster, J.C.; Schmidt, H. Supporting the development and documentation of ISO 27001 information security management systems through security requirements engineering approaches. In Engineering Secure Software and Systems; Barthe, G., Livshits, B., Scandariato, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Von Solms, R. Information Security Management: Processes and Metrics. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa, June 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, G. Managing Information System Security; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, July 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Candiwan, C. Analysis of ISO27001 implementation for enterprises and SMEs in indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyber-Crime Investigation and Cyber Security (ICCICS2014), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–19 November 2014; pp. 50–58.

- Whitman, M.; Mattord, H. Management of information security; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. Cybercrime: Threats and Solutions; Ark Group: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Furnell, S.M.; Gennatou, M.; Dowland, P.S. Promoting security awareness and training within small organisations. In Proceedings of the 1st Australian Information Security Management Workshop, Deakin University, Geelong, Australia, 7 November 2000.

- Schlienger, T.; Teufel, S. Information security culture—From analysis to change. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual IS South Africa Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 9–11 July 2003.

- Lichtenstein, S.; Swatman, P.M.C. Effective management and policy in E-business security. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Bled Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 25–26 June 2001.

- Cole, K.S.; Stevens-Adams, S.M.; Wenner, C.A. A Literature Review of Safety Culture; Sandia National Laboratories: Livermore, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosanas, J.M.; Velilla, M. The Ethics of management control systems: Developing technical and moral values. Bus. Ethics 2005, 53, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, E. The Human Factor in Security. Comput. Secur. 2005, 24, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugdol, M.; Jedynak, P. Integrated Management Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Von Solms, B. Information Security—The Third Wave? Comput. Secur. 2000, 19, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, G. The role of a stress model in the development of information security culture. In Proceedings of the MIPRO 35th International Convention, Opatija, Croatia, 21–25 May 2012.

- Magklaras, G.; Furnell, S. The insider misuse threat survey: Investigating IT misuse from legitimate users. In Proceedings of the 5th Australian Information Warfare & Security Conference, Perth, Western Australia, 25–26 November 2004; pp. 42–51.

- Dhillon, G.; Backhouse, J. Current directions in information systems security research: Toward socio-organizational perspectives. Inform. Syst. J. 2001, 11, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, D.F.; Polak, P. An empirical investigation of antecedents of internet abuse in the workplace. In Proceedings of the AIS SIG-HCI Workshop, Seattle, DC, USA, 12–13 December 2003.

- CSI/FBI. Tenth Annual CSI/FBI Computer Crime and Security Survey; Computer Security Institute: College Park, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ISBS. Information Security Breaches Survey 2006; Department of Trade and Industry: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- AusCERT. Australian Computer Crime and Security Survey; AusCERT: Gold Coast, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst&Young. 2006 Global Information Security Survey; EYGM Limited: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DTI. The Empirical Economics of Standards; Department of Trade and Industry: London, UK; Available online: http://www.immagic.com/eLibrary/ARCHIVES/GENERAL/UK_DTI/T050602D.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2016).

- OECD. OECD Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems and Networks: Towards a Culture of Security; OECD, Ed.; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, C.B. Qualitative methods in empirical studies of software engineering. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1999, 25, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avison, D.; Lau, F.; Myers, M.D.; Nielsen, P.A. Action research. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genero, M.; Cruz-Lemus, J.A.; Piattini, M. Investigación-Acción. In Métodos de Investigación en Ingeniería del Software; RA-MA, Ed.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.; Eloff, J.H.P. Information Security Culture. In Proceedings of the IFIP TC11 17th International Conference on Information Security (SEC2002), Cairo, Egipt, 7–9 May 2002.

- Schlienger, T.; Teufel, S. Information security culture: The socio-cultural dimension in information security management. In IFIP TC11 17th International Conference on Information Security (SEC2002), Cairo, Egipt, 7–9 May 2002.

- Nosworthy, J. Implementing information security in the 21st century—Do you have the balancing factors. Comput. Secur. 2000, 19, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, O.; Gani, A. A conceptual checklist of information security culture. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Information Warfare and Security, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 30 June–1 July 2003.

- Zakaria, O.; Jarupunphol, P.; Gani, A. Paradigm mapping for information security culture approach. In Proceedings of the 4th Australian Conference on Information Warfare and IT Security, Adelaide, Australia, 20–21 November 2003.

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, P.A.; Ruighaver, A.B.; Maynard, S.B. Understanding organizational security culture. In Proceedings of the PACIS Security Culture, Tokyo, Japan, 2–3 September 2002.

- Siponen, M.T. A conceptual foundation for organizational information security awareness. Inform. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2000, 8, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Solms, B.; Von Solms, R. Incremental information security certification. Comput. Secur. 2001, 20, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, C.; Von Solms, R. Towards information security behavioural compliance. Comput. Secur. 2004, 23, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.A.; Maynard, S.B.; Ruighaver, A.B. Exploring organisational security culture: Developing a comprehensive research model. In Proceedings of the IS ONE World Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–5 April 2002.

- Helokunnas, T.; Kuusisto, R. Information security culture in a value net. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Engineering Management Conference (IEMC 2003), Albany, NY, USA, 2–4 November 2003.

- Straub, D.; Loch, K. Toward a theory-based measurement of culture. Glob. Inform. Manag. 2002, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, T.; Ilvonen, I. Information security culture in small and medium size enterprises. In Frontiers of e-Business Research 2003; Tampere University of Technology & University of Tampere: Tampere, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Detert, J.; Schroeder, R.; Mauriel, A.J. A framework for linking culture and improvement initiatives in organisations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 850–863. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.; Murphy, A. SMEs and eBusiness. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2004, 11, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, D.; Armitt, C.; Edwards-Lear, D. The application of an agile approach to it security risk management for SMES. In Proceedings of the 12th Australian Information Security Management Conference, Perth, Australia, 1–3 December 2014.

- Dojkovski, S.; Lichtenstein, S.; Warren, M.J. Challenges in fostering an information security culture in australian small and medium sized enterprises. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Information Warfare and Security, Helsinki, Finland, 1–2 June 2006.

- Hutchinson, D.; Warren, M. e-Business Security Management for Australian Small SMEs—A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 7th International We-B (Working for E-Business) Conference: e-Business: How Far Have We Come? Orlando, Florida, 11–13 June 2006.

- Dimopoulos, V.; Furnell, S.; Jennex, M.E.; Kritharas, I. Approaches to IT security in small and medium enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2nd Australian Information Security Management Conference, Securing the Future, Perth, Australia, 26 November 2004; pp. 73–82.

- Helokunnas, T.; Iivonen, L. Information security culture in small and medium size enterprises. In e-Business Research Forum—eBRF 2003; Tampere University of Technology: Tampere, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M.J. Australia’s agenda for E-security education and research. In Proceedings of the TC11/WG11.8 Third Annual World Conference on Information Security Education (WISE3), Naval Post Graduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, 26–28 June 2003.

- Von Solms, R.; Von Solms, B. From policies to culture. Comput. Secur. 2004, 23, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnell, S.M.; Clarke, N.L. Organisational security culture: Embedding security awareness, education and training. In Proceedings of the 4th World Conference on Information Security Education (WISE 2005), Moscow, Russia, 18–20 May 2005.

- Van Niekerk, J.C.; Von Solms, R. Establishing an information security culture in organisations: An outcomes-based education approach. In Proceedings of the ISSA 2003:3rd Annual IS South Africa Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 9–11 July 2003.

- Hutchinson, D.; Warren, M. Australian SMES and e-security guides on trusting the internet. In Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Global Information Technology Management World Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 8–10 June 2003.

- Knapp, K.J.; Marshall, T.E.; Rainer, R.K.; Ford, F.N. Information security: Management’s effect on culture and policy. Inform. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2006, 14, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, S. Internet Security Policy for Organisations. Ph.D. Thesis, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, J.M.; Stam, K.R.; Mastrangelo, P.; Jolton, J. Analysis of end-user security behaviors. Comput. Secur. 2004, 24, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, S.; Swatman, P.M.C. The potentialities of focus groups in e-Business research: Theory validation, in seeking success in e-Business: A multi-disciplinary approach. In IFIP TC8/WG 8.4 Second Working Conference on E-business: Multidisciplinary Research and Practice; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Furnell, S.; Warren, A.; Dowland, P.S. Improving security awareness and training through computer-based training. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Information Security Education (WISE 2004), Monterey, CA, USA, 26–28 July 2004.

- Dutta, A.; McCrohan, K. Management’s role in information security in a cyber economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneza, D.; Sharman, L.; John, W.M. Fostering information security culture in small and medium size enterprises: An interpretive study in australia. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Information Systems, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 7–9 June 2007.

- ABS. 1321.0—Small Business in Australia; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Hammond, R. Information systems security issues and decisions for small businesses. Inform. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2005, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, J. ICT business management for SMEs. Comput. Weekly. Available online: http://www.computerweekly.com/feature/ICT-business-management-for-SMEs (accessed on 4 June 2016).

- Dhillon, G. Violation of safeguards by trusted personnel and understanding related information security concerns. Comput. Secur. 2001, 20, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.E.; Santos-Olmo, A.; Fernández-Medina, E.; Piattini, M. ISMS building for SMEs through the reuse of knowledge. In Small and Medium Enterprises: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, L.E.; Santos-Olmo, A.; Rosado, D.G.; Piattini, M. Managing security and its maturity in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. UCS 2009, 15, 3038–3058. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Olmo, A.; Sánchez, L.E.; Fernández-Medina, E.; Piattini, M. Desirable characteristics for an ISMS oriented to SMEs. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Security in Information Systems (WOSIS11), Beijing, China, 2–5 June 2011; pp. 151–158.

- Santos-Olmo, A.; Sánchez, L.E.; Fernández-Medina, E.; Piattini, M. A Systematic Review of Methodologies and Models for the Analysis and Management of Associative and Hierarchical Risk in SMEs. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Security in Information Systems (WOSIS12), Wroclaw, Poland, 28 June–1 July 2012; pp. 117–124.

- ISO/IEC27001. ISO/IEC 27001:2013, Information Technology—Security Techniques Information Security Management Systemys—Requirements; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC27002. ISO/IEC 27002:2013, the International Standard Code of Practice for Information Security Management (en Desarrollo); International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, L.E.; Santos-Olmo, A.; Fernández-Medina, E.; Piattini, M. Building ISMS through the Reuse of Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Trust, Privacy & Security in Digital Business (TRUSTBUS’10), Bilbao, Spain, 30–31 August 2010; Springer: Bilbao, Spain; pp. 190–201.