HEXADWSN: Explainable Ensemble Framework for Robust and Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection in WSNs

Abstract

1. Introduction

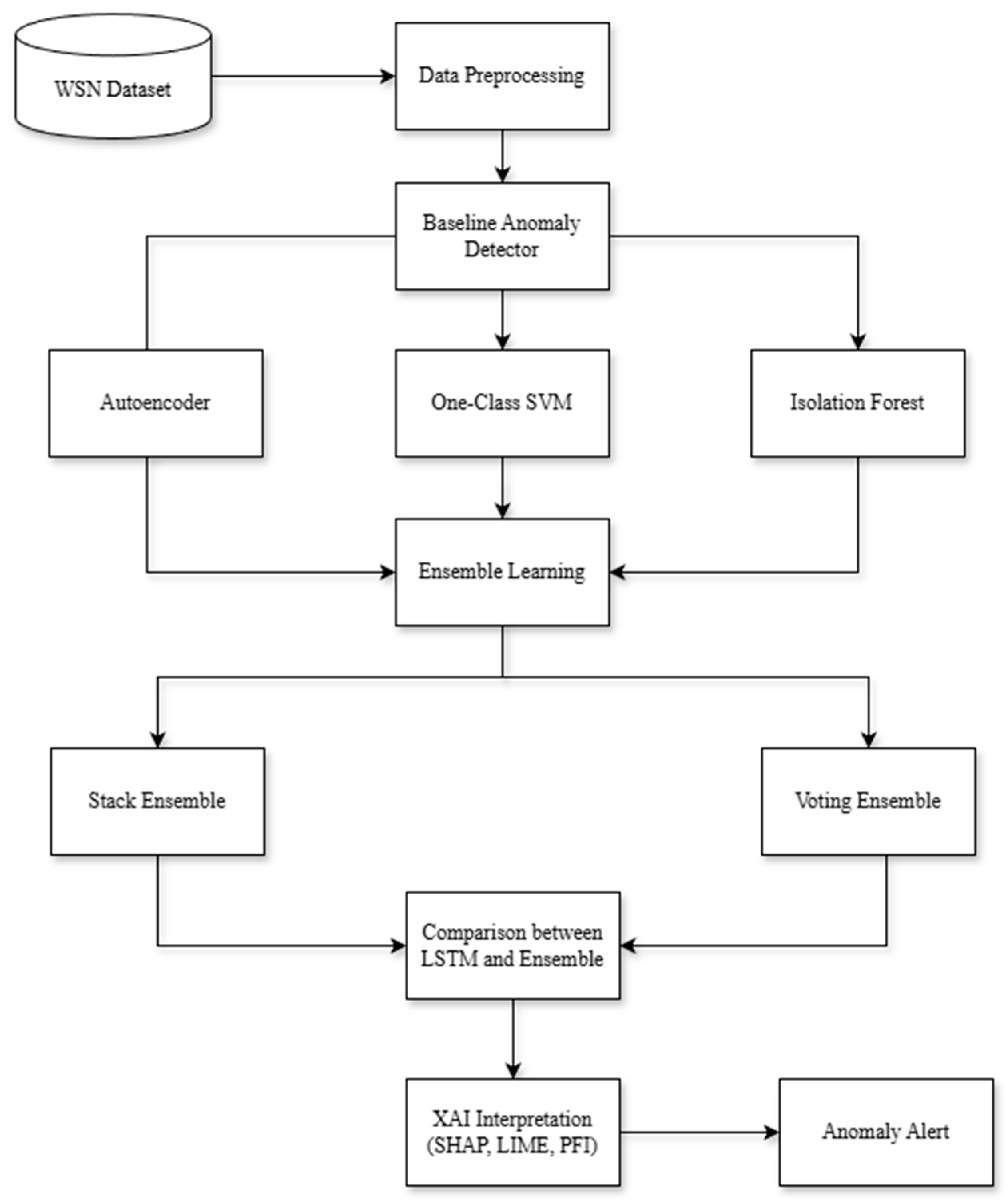

- Preprocessing includes per-mote resampling, temporal feature engineering, adaptive outlier clipping, and normalisation, ensuring clean and context-rich inputs suitable for a variety of unsupervised modelling techniques.

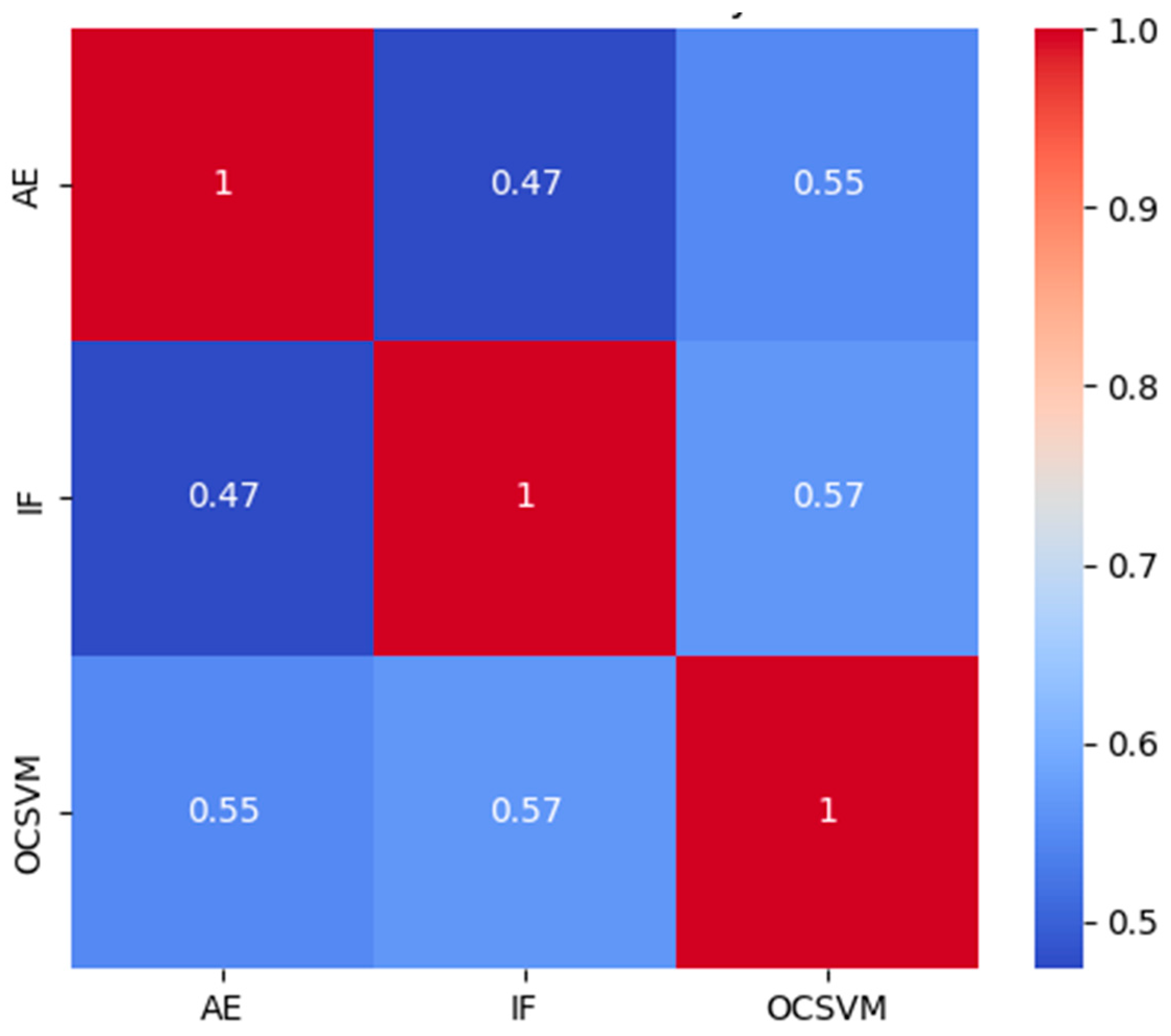

- The HEXADWSN combines AE, IF, and OCSVM into an ensemble framework. The ensemble framework is tested using voting and stacking methods to balance detection accuracy with interpretability and operational relevance.

- The HEXADWSN integrates SHAP, LIME and PFI methods that provide both global and local explanations to enhance transparency and enable actionable insights into the root causes of anomalies.

- SN-level energy consumption and its temporal fluctuations in conjunction with anomaly labels are estimated to enable energy-aware maintenance strategies in real-world networks.

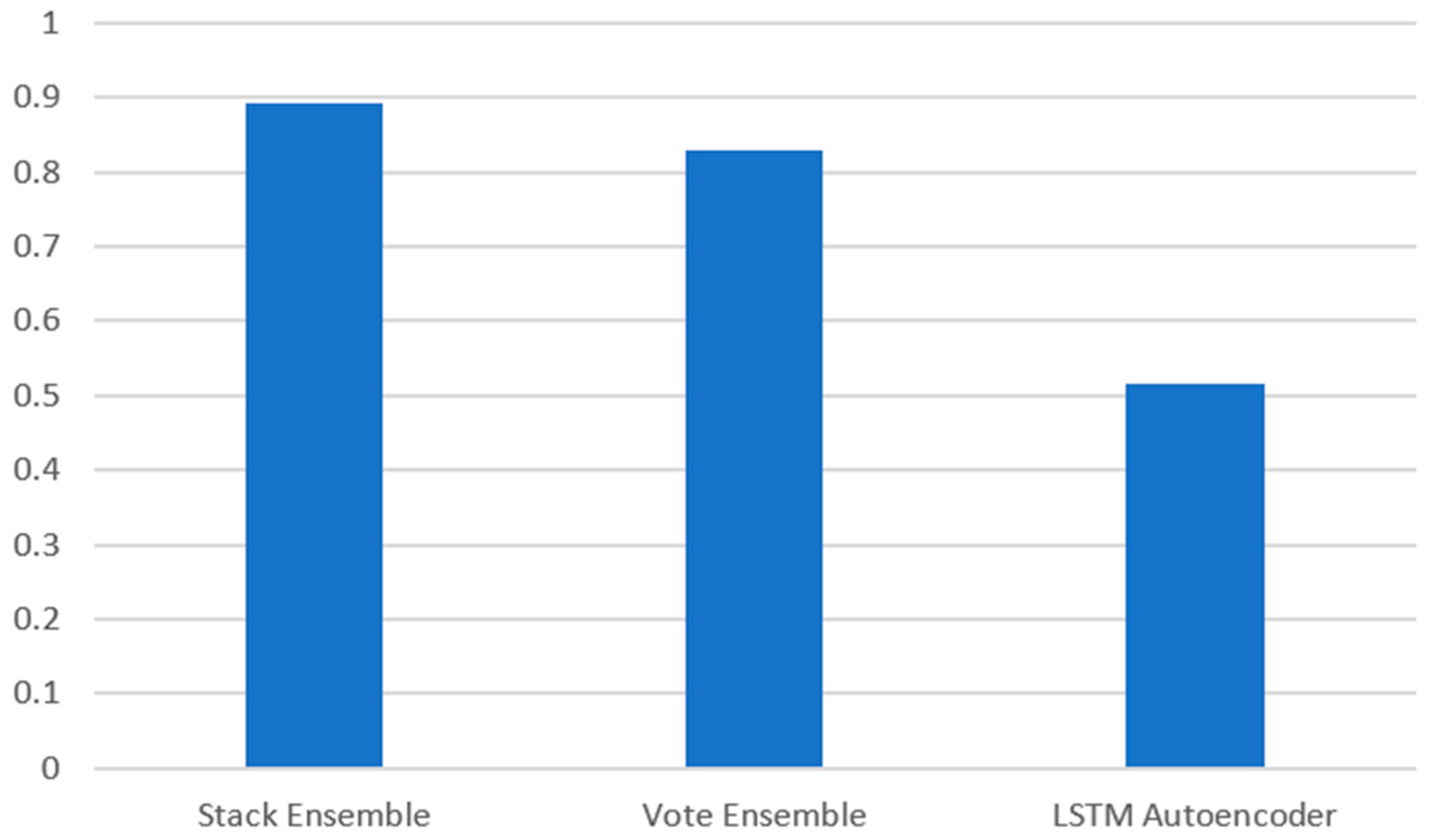

- The framework benchmarks voting and stacking ensembles against an LSTM-based model to demonstrate the trade-offs and complementary strengths in handling the temporal nature of data.

2. Related Work

- Statistical and Rule-Based Methods: Traditional statistical approaches use rule-based methods such as mean and variance to identify anomalies. Rule-based systems quickly differentiate between normal and compromised traffic, particularly effective against DoS attacks. These methods are simple and computationally efficient yet struggle with dynamic environmental changes and complex dependencies in the data, making them unsuitable for real-time monitoring [11]. Statistical techniques are used to identify correlations in the SD, and Markov models are used to differentiate normal network behaviour. These approaches can detect external and internal threats but do not address the unique challenges posed by the constraints of WSN resources and vulnerability to attacks [12,13].

- ML-Based Methods: ML-based techniques have emerged as effective tools for anomaly detection in WSNs. Various techniques have been used, such as Bayesian classification, Online Locally Weighted Projection Regression, and Support Vector Machines, which have demonstrated high detection rates and low false positive rates, addressing challenges such as hardware failures, physical tampering, software failures, and environmental factors [14]. The ML-based techniques can be categorised into three main categories: supervised, unsupervised, or semi-supervised. Each offers unique advantages for anomaly detection. Supervised learning is effective for anomaly detection, as it can differentiate between normal and anomalous behaviour by learning from a labelled dataset, while the unsupervised technique does not depend upon labelled data for training and can discover hidden patterns to identify unusual behaviour, whereas semi-supervised learning combines supervised and unsupervised learning for anomaly detection [15]. The uses of ML-based techniques in WSNs have shown promising results in various domains; still, various challenges such as handling noisy and unreliable data and adapting to the resource-constrained nature of WSNs remain unaddressed [16].

- Deep Learning Approaches: Several studies have explored DL-based methods for anomaly detection in WSN. These approaches aim to improve security and reliability by identifying potential threats and attacks in the network. A hybrid Deep Generative Model with Isolation Forest (DGM-IF) has been presented that combines DL with the IF algorithm to detect anomalies in an unsupervised manner [17]. The IoT-AnomalyNet model integrates deep learning techniques and achieves high accuracy in real-time anomaly detection for IoT networks [18]. A graph-based deep learning approach has shown potential for anomaly detection in WSNs [19]. A cyber-attack detector method based on deep learning and a combination of CNN and LSTM techniques has demonstrated improved detection accuracy compared to traditional ML-based techniques [20]. These studies highlight the effectiveness of deep learning approaches to address the security challenges faced by WSNs and IoT systems.

- Hybrid ML Models: The SVM-RFNet model combines SVMs, Random Forests, and neural networks, achieves 96% precision in real-time anomaly detection by leveraging feature engineering techniques like PCA [21]. In [22], real-time anomaly detection techniques are presented using Online Adaptive Kalman Filtering (OAKF) to dynamically adjust the parameters to achieve a 95.4% precision while minimizing the false positives and processing time. In [23], a trap-based anomaly detection mechanism is used for deceptive nodes to lure attackers to improve network security and energy efficiency while providing early warning of potential threats.

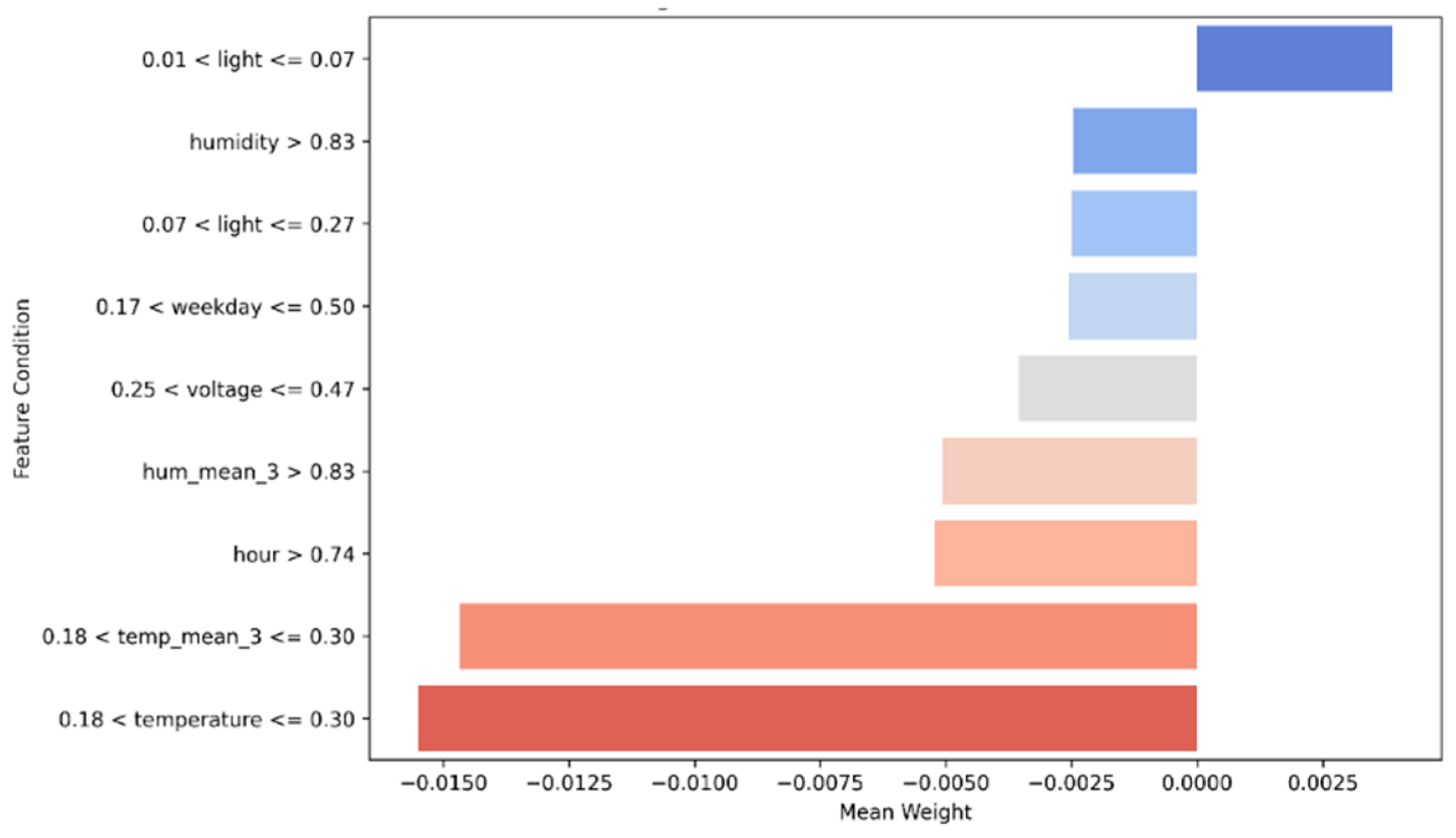

- SHAP: Based on game theory, SHAP assigns an importance value to each feature, explaining how much it contributes to the model’s prediction. It provides a global feature importance analysis, helping to understand why anomalies occur over time [28].

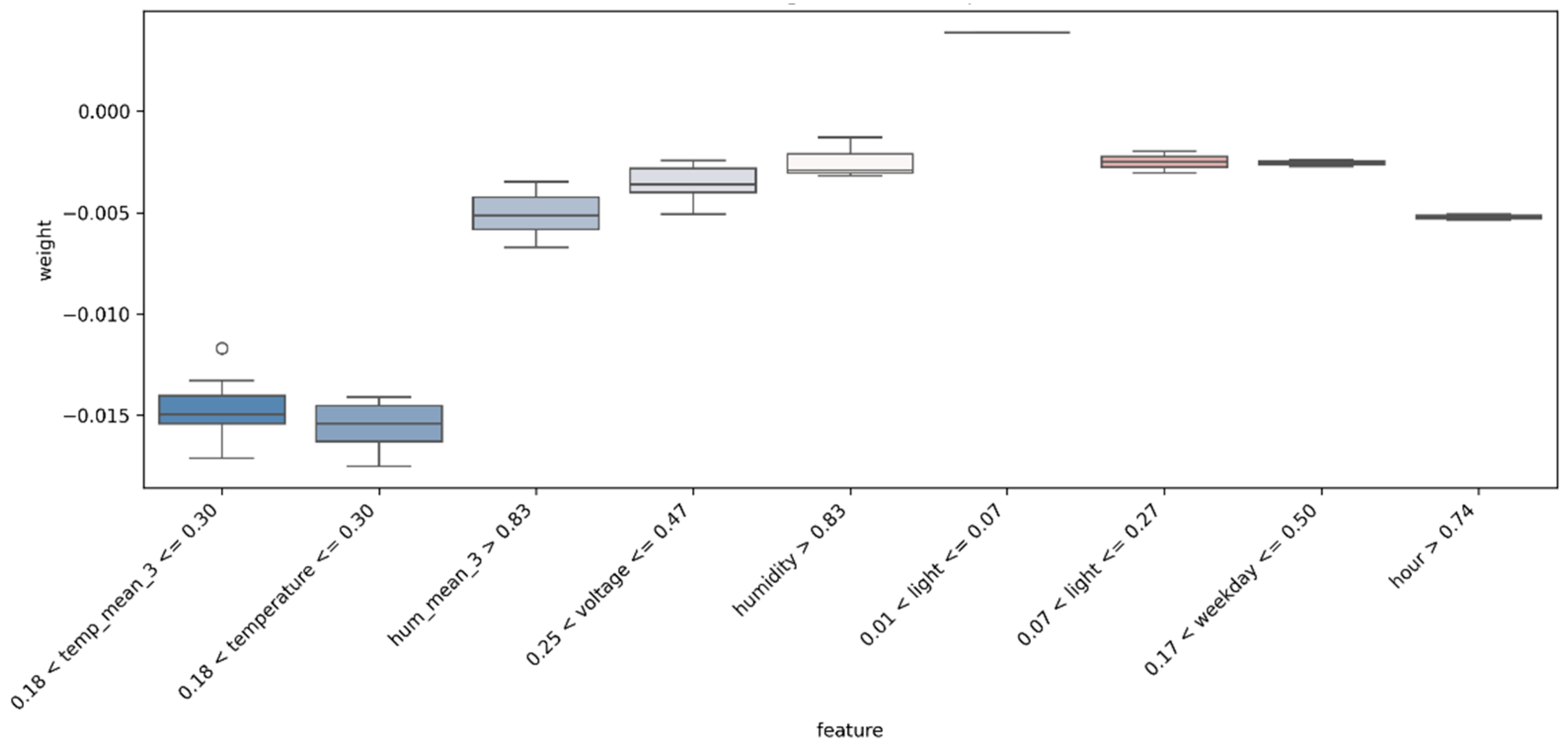

- LIME: Generates locally interpretable explanations by perturbing individual data instances and approximating the model’s behaviour with a simpler surrogate model. It is useful for understanding specific anomaly cases in WSNs [29].

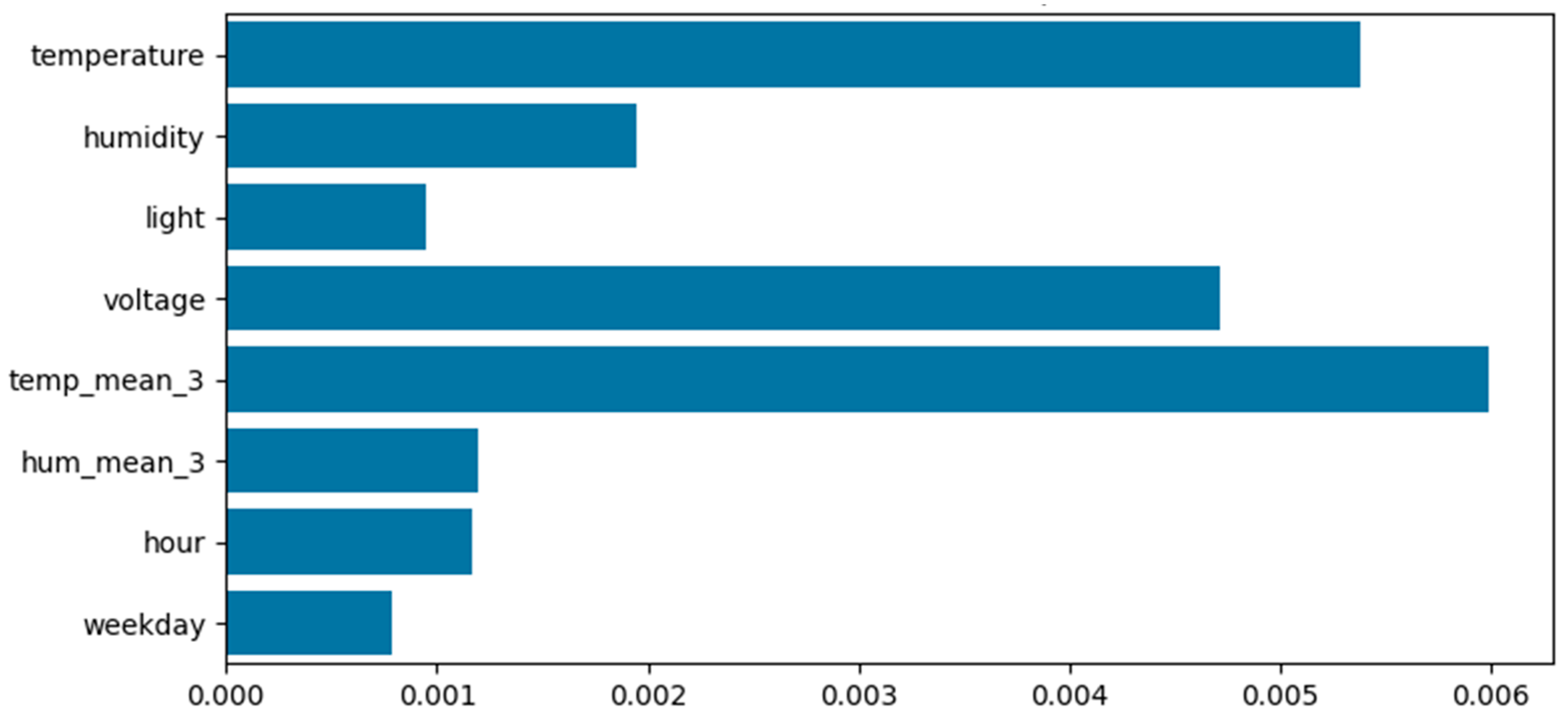

- PFI: A model-agnostic interpretability technique that quantifies the importance of each feature by measuring how much the model’s predictive performance deteriorates when the feature’s values are randomly shuffled in the validation or test data [30].

- Utilise baseline methods AE, IF, and OCSVM to effectively detect anomalies in WSN data;

- Apply stack ensemble and vote ensemble on baseline methods to compare the anomaly detection performance;

- Apply SHAP and LIME to understand the importance of local and global features in anomalies;

- Use PFI to understand the importance of features across models.

3. Proposed Methodology

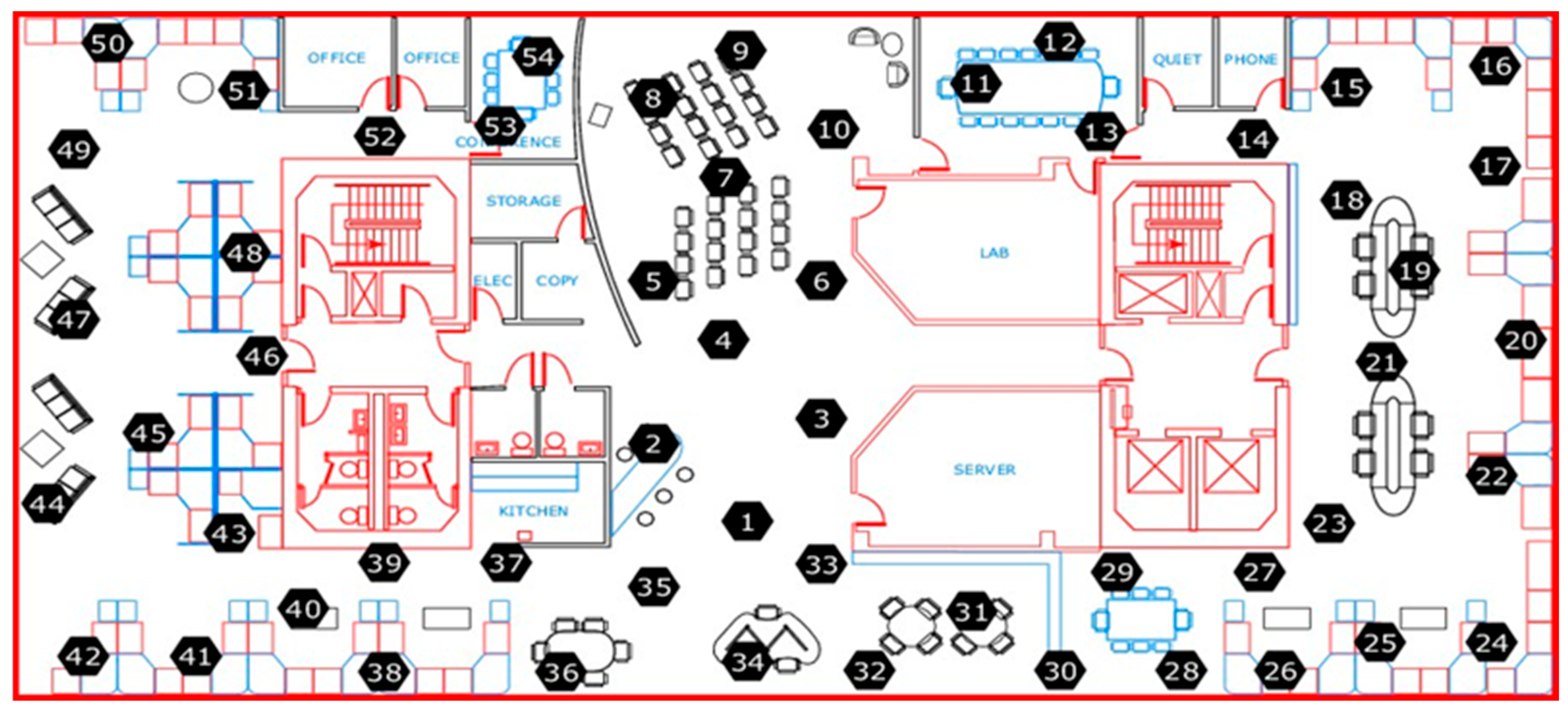

3.1. Dataset Description and Preprocessing

3.2. Anomaly Detection Methods

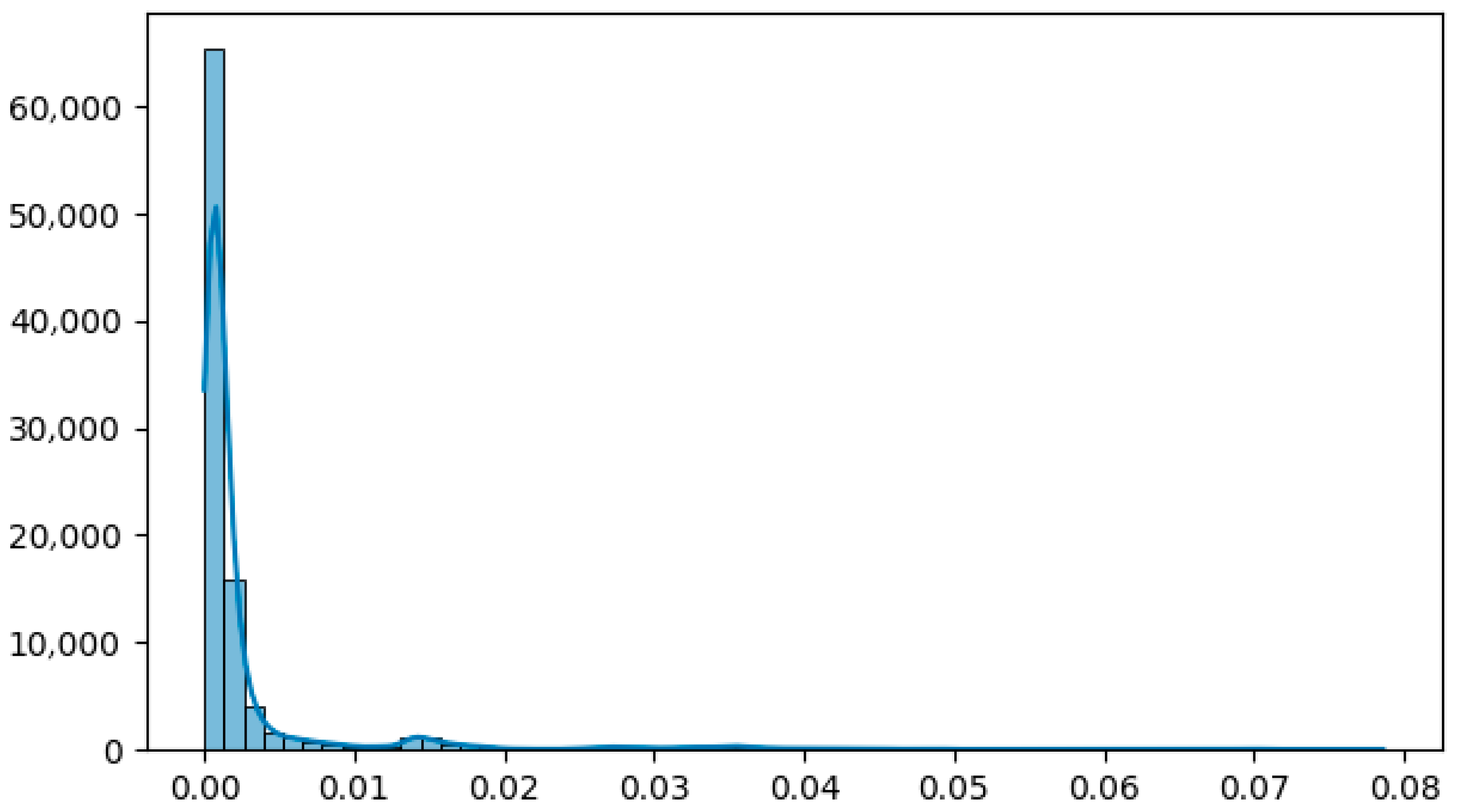

- Autoencoder: A neural network with an hourglass structure is trained to reconstruct normal input. Deviations in reconstruction error are flagged as anomalies. Adaptive thresholds are estimated with a Gaussian mixture fit on residual error distributions and, for robustness, a fixed quantile rule [24]. The loss function used in the autoencoder is the Mean Squared Error, defined using Equation (1).where represents the original input and is the reconstructed output. A higher reconstruction error suggests a greater deviation from normal patterns, indicating potential anomalies. The training data consists solely of normal sensor readings, ensuring that the autoencoder learns the underlying distribution of non-anomalous data. For anomaly detection, a threshold is established using either a percentile-based method. Any instance with a reconstruction error that exceeds this threshold is classified as an anomaly [42].

- Isolation Forest: IF works on the principle that anomalies are data points that are few and different in the dataset and therefore easy to isolate compared to normal points. IF randomly partition the data using random partitioning without reliance on distributional assumptions. This makes it scalable and computationally inexpensive for WSNs [43].

- One-Class SVM: Kernel-based support vector technique learns the smallest hypersphere or separating hyperplane on normal data. When detecting data falling outside the learned boundary flagged as an anomaly. OCSVM can handle high-dimensional data [44].

3.3. Energy Estimation

3.4. Explainability and Feature Importance

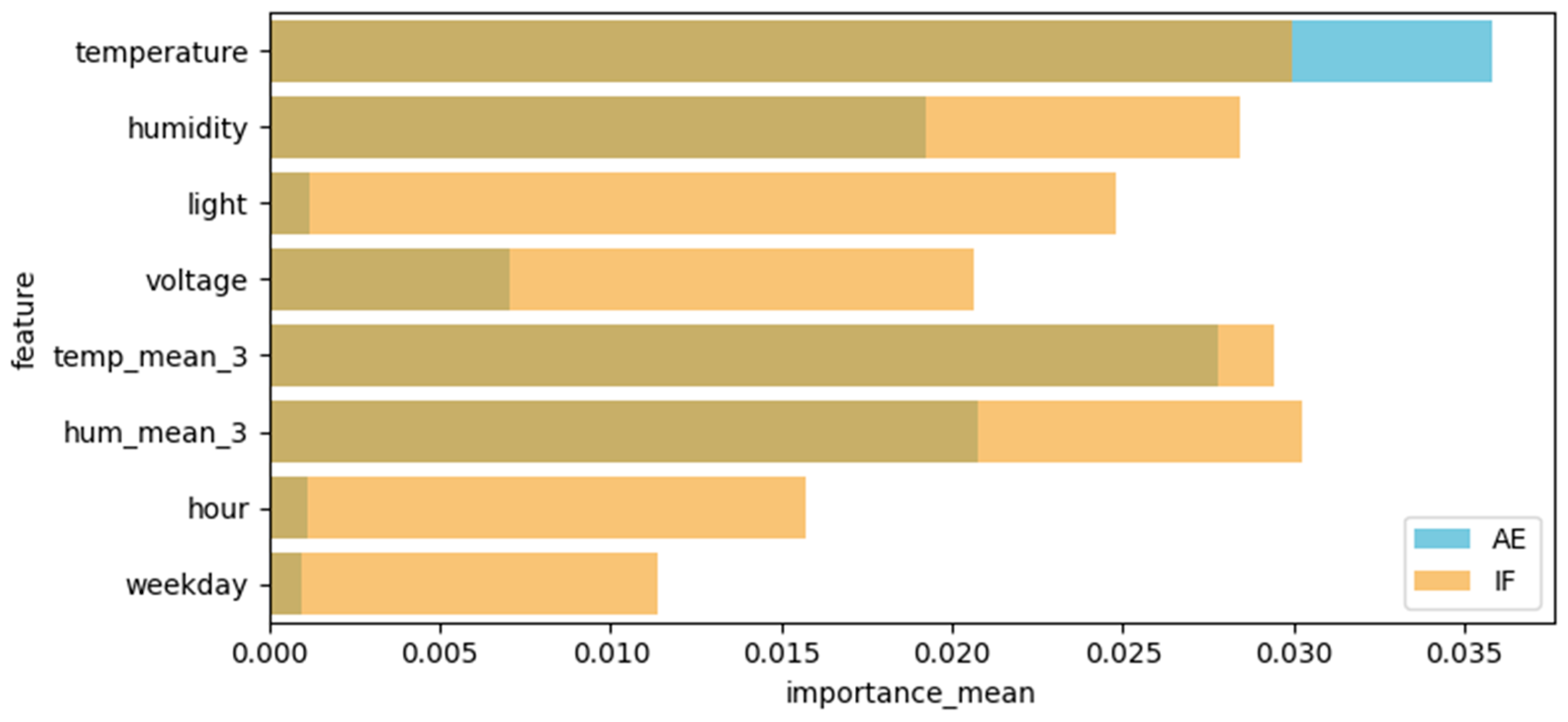

- PFI: Measures feature impact for the AE and IF over test data;

- SHAP: Computes feature-level contributions to reconstruction error for individual and global cases, facilitating root-cause diagnosis;

- LIME: Provides instance-specific feature rules for anomalies detected by the AE.

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Work

- Adaptive and contextual thresholding: Developing dynamic, context-aware thresholds that adjust in response to environmental changes and sensor drift will improve anomaly discrimination consistency over time.

- Advanced Temporal Modelling: Incorporating more sophisticated temporal architectures, such as Transformers or graph-based sequence models, could further enhance detection of complex spatiotemporal anomaly patterns.

- Edge Deployment Optimisation: Investigating methods for model compression, quantization, or decentralised inference on WSN edge devices will enable real-time, on-node anomaly detection, reducing communication overhead and energy consumption.

- Cross-Dataset Generalisation: Evaluating HEXADWSN in diverse WSN datasets across application domains will validate model robustness and support transfer learning strategies.

- Interactive Explainability: Integrating counterfactual and contrastive explanation methods can provide operators with actionable recommendations, translating anomaly detections into mitigative actions.

- Energy-aware Reinforcement Learning: Investigating reinforcement learning frameworks that optimise anomaly detection accuracy jointly with energy efficiency and network longevity objectives.

- Hybrid Graph-Learning Extensions: Applying graph neural networks and temporal attention models to capture spatial–temporal correlations across motes.

- Causal Explainability Integration: Extending SHAP/LIME with causal models to differentiate between correlated and causative anomaly factors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Anomaly Detection Technique |

| AE | Autoencoder |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AoI | Area of Interest |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| IF | Isolation Forest |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory-based Autoencoder |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| OCSVM | One-Class SVM |

| PFI | Permutation Feature Importance |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SN | Sensor Node |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| WSNs | Wireless Sensor Network |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Hossam, F.; Ahmad, M.; WSNs Applications. Concepts, Applications, Experimentation and Analysis of Wireless Sensor Networks; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 67–242. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Jha, S.K. Efficient Zone Routing through KNearest Neighbours Optimization in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 December 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, R.S.; Sangwan, S.; Prakash, S.; Adhikari, K.; Kharel, R.; Cao, Y. Hybrid WGWO: Whale grey wolf optimization-based novel energy-efficient clustering for EH-WSNs. J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2020, 2020, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztoprak, A.; Hassanpour, R.; Ozkan, A.; Oztoprak, K. Security challenges, mitigation strategies, and future trends in wireless sensor networks: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheyaaldin, A. A comparative study of anomaly detection techniques for IoT security using adaptive machine learning for IoT threats. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 14719–14730. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.; Kong, X.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Lv, W. Enhancing anomaly detection accuracy and interpretability in low-quality and class imbalanced data: A comprehensive approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascita, A.; Aceto, G.; Ciuonzo, D.; Montieri, A.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence for internet traffic classification and prediction, and intrusion detection. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 27, 3165–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortigossa, E.S.; Gonçalves, T.; Nonato, L.G. Explainable artificial intelligence (xai)—From theory to methods and applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 80799–80846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, G.; Silva, P.; Silva, C. Explainable AI for intrusion detection systems: LIME and SHAP applicability on multi-layer perceptron. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30164–30175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, P.; Mondal, A.K.; Mondal, H.K.; Mohanty, S.P. EasyDiagnos: An Accurate Feature Selection Framework for Automated Diagnosis in Smart Healthcare. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, S.; Singh, P.; Chauhan, S.S. Design and Analysis of an Integrated Rule-Based and Machine Learning System for DoS Attack Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences and Engineering (IC3SE), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 9–11 May 2024; pp. 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabseh, A.; Faizan, M. Outlier Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks Using Machine Learning and Statistical Based Approaches. Rev. D’intell. Artif. 2024, 38, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.W.A.; Singh, A.R.; Pandian, A.; Rathore, R.S.; Bajaj, M.; Zaitsev, I. A hybrid approach using support vector machine rule-based system: Detecting cyber threats in internet of things. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadia, H.; Farhan, S.; Haq, Y.U.; Sana, R.; Mahmood, T.; Bahaj, S.A.O.; Khan, A.R. Intrusion detection system for wireless sensor networks: A machine learning based approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 52565–52582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Balyan, A.; Singh, A.K. Machine learning-based energy optimization and anomaly detection for heterogeneous wireless sensor network. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, B.; Saoud, B.; Shayea, I.; Leila, R. Outlier Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN), Indore, India, 22–23 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zerkouk, M.; Mihoubi, M.; Chikhaoui, B. Deep Generative Model with Isolation Forest (DGM-IF) for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection in Wireless Sensor Network and Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Rome, Italy, 3–6 July 2023; pp. 2275–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Sudharson, K.; Anita, C.S.; Berlin, M.A.; Petchiammal, G.E.; Deepika, J.; Selvi, K. Real-Time Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using Deep Learning over Wireless Channels. SSRG Int. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 11, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen, R.F.; Hämäläinen, T. Network Anomaly Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review. In Next Generation Teletraffic and Wired/Wireless Advanced Networking; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, S.M.; Ali, Y.H.; Al-Jumeily, D. Deep learning model for cyber-attacks detection method in wireless sensor networks. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2022, 10, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifani, S.A.; Mary, A.A.; Metilda, M.M.; Rajkumar, G.V.; Sutha, S.M.; Maheshwari, S. A Novel Machine Learning Strategy for Anomaly Identification Scheme in Wireless Sensor Networks Using Supervised Training Principles. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Coimbatore, India, 7–9 August 2024; pp. 1754–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.; Alkhammash, E.H. Online Adaptive Kalman Filtering for Real-Time Anomaly Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, D.; Roy, P.; Mishra, A. Trap Based Anomaly Detection Mechanism for Wireless Sensor Network. ASEAN Eng. J. 2024, 14, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Qiu, H. A Novel Self-Supervised Learning-Based Anomalous Node Detection Method Based on an Autoencoder for Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Nagarajan, S.G. Distributed Anomaly Detection Using Autoencoder Neural Networks in WSN for IoT. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Kansas City, MO, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yeo, C.K.; Lee, B.S.; Lau, C.T. Autoencoder-based network anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 Wireless Telecommunications Symposium (WTS), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.; Obaidat, M.S.; Shah, D.; Shah, S.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S.; Bhatia, J. X-SENSE: Explainable ML-based Intelligent Sensor Environment for Wireless Network Security. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computer, Information and Telecommunication Systems (CITS), Colmar, France, 16–18 July 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dhananjaya, S.A.K.; Lakmal, H.K.I.S.; Nirmal, W.C. Evaluating the Features of Indoor Positioning Systems Using Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th SLAAI International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (SLAAI-ICAI), Ratmalana, Sri Lanka, 18–19 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tserenkhuu, M.; Hossain, D.; Taenaka, Y.; Kadobayashi, Y. Intrusion Detection System framework for SDN-based IoT networks using deep learning approaches with XAI-based feature selection techniques and domain-constrained features. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 136864–136880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ali, A.; Khan, J.; Ullah, F.; Faheem, M. Using Permutation-Based Feature Importance for Improved Machine Learning Model Performance at Reduced Costs. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 36421–36435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, D.; Dini, P.; Soldaini, E.; Saponara, S. One-Class Anomaly Detection for Industrial Applications: A Comparative Survey and Experimental Study. Computers 2025, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Nigam, S.; Vijay, E.; Rathore, R.; Bhosale, S.; Deogirikar, A. Adaptive anomaly detection in sensor data: A comprehensive approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Technology & Engineering Management Conference-Asia Pacific (TEMSCON-ASPAC), Bengaluru, India, 14–16 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- John, A.; Bin Isnin, I.F.; Madni, S.H.H.; Faheem, M. Intrusion detection in cluster-based wireless sensor networks: Current issues, opportunities and future research directions. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. 2024, 14, 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.S.; Alqurashi, A.; Alharbi, T.E.; Alammar, M.M.; Aldosari, N.; Bouchekara, H.R.E.H.; Sha’aBan, Y.A.; Shahriar, M.S.; Al Ayidh, A.; Shaaban, Y. Explainable AI for Sensor Signal Interpretation to Revolutionize Human Health Monitoring: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 115990–116024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummadi, A.N.; Napier, J.C.; Abdallah, M. XAI-IoT: An explainable AI framework for enhancing anomaly detection in IoT systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 71024–71054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Kifayat, K.; Sampedro, G.A.; Karovič, V.; Naeem, T. SXAD: Shapely eXplainable AI-based anomaly detection using log data. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95659–95672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, M.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Maheshkumar, K.; Aiswarya, A.; Pveena, S. Enhancing Sustainable Agriculture with IoT-Based Soil Fertility and Crop Selection Using Hybrid Stacked Ensemble Models and Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 22–24 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignone, P.; Corizzo, R.; Ceci, M. Distributed and explainable GHSOM for anomaly detection in sensor networks. Mach. Learn. 2024, 113, 4445–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birahim, S.A.; Paul, A.; Rahman, F.; Islam, Y.; Roy, T.; Hasan, M.A.; Haque, F.; Chowdhury, M.E.H. Intrusion Detection for Wireless Sensor Network Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based Explainable Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13711–13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraj, A.; Szczepaniak, P.S.; Sadok, A. Detection of Anomalies in Data Streams Using the LSTM-CNN Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intel Lab Data. Available online: https://db.csail.mit.edu/labdata/labdata.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Rassam, M.A. Autoencoder-Based neural network model for anomaly detection in wireless body area networks. IoT 2024, 5, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, S. Hybrid Anomaly Detection Model Integrating Lstm and Isolation Forest for Enhanced Performance in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 25–27 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, K.; Velmurugan, K.J.; Vidhya, R.; Sudha, S.R. Deep anomaly detection: A linear one-class SVM approach for high-dimensional and large-scale data. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Qin, T.; Wei, W.; Fan, Y.; Yang, J. An energy consumption optimization strategy for Wireless sensor networks via multi-objective algorithm. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelman, W.; Chandrakasan, A.; Balakrishnan, H. Energy-efficient communication protocol for wireless microsensor networks. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2000; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.P.; Garg, S.; Alabdulkreem, E.; Ben Miled, A. Advanced generative adversarial network for optimizing layout of wireless sensor networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ML Model | Integrated XAI |

|---|---|

| Multiple single and ensemble AI models [35] | Used SHAP, LOCO, ALE, PFI, and ProWeight for explainability |

| Decision Tree, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting [36] | Kernel SHAP is used for explainability purposes. The Kernel SHAP is model-agnostic and versatile but is computationally expensive |

| In [37] CNN, XGBoost, LSTM, and Random Forest are used for initial training of the model and final prediction is performed using a Neural Network meta-model | SHAP and LIME are used for explainability purposes |

| TinyML, LSTM, and GRU [38] | SHAP and LIME |

| Autoencoder, GNN, and GRU [39] | The paper does use any explicit XAI. However, the hybrid design focuses on spatial–temporal fusion |

| CNN, LSTM [40] | No explicit XAI |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Date and Time | Timestamp of the data recording yyyy-mm-dd is the format to record the date whereas time is recorded in hh:mm:ss.xxx format. |

| Epoch | Epoch is the system-generated sequence number from each node. |

| Mote-ID | Mode-ID is the unique identification number of each SN, ranging from 1 to 54. |

| Temperature | The temperature recorded by the SNs in degrees Celsius. |

| Humidity | Humidity is the percentage of humidity detected, ranging from 0 to 100%. |

| Light | Intensity of light measured by the sensors in Lux. |

| Voltage | Battery voltage of the sensor node, measured in volts (ranging from 2 to 3 V). |

| Model | Anomalies | Mean Energy (Anomalous/Normal) |

|---|---|---|

| AE | 9742 | 0.1517/0.2280 |

| IF | 5945 | 0.2639/0.2174 |

| OCSVM | 9144 | 0.2270/0.2196 |

| Stack Ensemble | 6834 | 0.1884/0.2227 |

| Vote Ensemble | 7657 | 0.2125/0.2210 |

| Model | F1 | Precision | Recall | Accuracy | ROC-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stack Ensemble | 0.6932 | 0.5981 | 0.8265 | 0.9834 | 0.8924 |

| Vote Ensemble | 0.5074 | 0.4067 | 0.6744 | 0.9771 | 0.8285 |

| LSTM Autoencoder | 0.0479 | 0.0543 | 0.0429 | 0.9702 | 0.5148 |

| Feature | PFI-AE | PFI-IF | SHAP Value (Mean) | LIME Weight (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| temperature | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.0058 | −0.011 |

| humidity | 0.029 | 0.026 | 0.0020 | −0.009 |

| light | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.0008 | −0.005 |

| voltage | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.0045 | −0.007 |

| temp_mean_3 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.0060 | −0.013 |

| hum_mean_3 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.0013 | −0.009 |

| hour | 0.010 | 0.016 | 0.0011 | −0.006 |

| weekday | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.0007 | −0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishra, R.; Jha, S.K.; Prakash, S.; Rathore, R.S. HEXADWSN: Explainable Ensemble Framework for Robust and Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection in WSNs. Future Internet 2025, 17, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110520

Mishra R, Jha SK, Prakash S, Rathore RS. HEXADWSN: Explainable Ensemble Framework for Robust and Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection in WSNs. Future Internet. 2025; 17(11):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110520

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishra, Rahul, Sudhanshu Kumar Jha, Shiv Prakash, and Rajkumar Singh Rathore. 2025. "HEXADWSN: Explainable Ensemble Framework for Robust and Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection in WSNs" Future Internet 17, no. 11: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110520

APA StyleMishra, R., Jha, S. K., Prakash, S., & Rathore, R. S. (2025). HEXADWSN: Explainable Ensemble Framework for Robust and Energy-Efficient Anomaly Detection in WSNs. Future Internet, 17(11), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17110520