1. Introduction

Generative AI has rapidly evolved from a niche research field to a mainstream technology with diffusion models, transformers, and large language models producing high-quality images, music, and text on demand [

1,

2,

3]. In parallel, agentic workflows that orchestrate multiple specialized AI agents are transforming complex creative and analytical processes [

4]. These developments open unprecedented opportunities for computational creativity but also raise new questions about how to design, control, and evaluate AI-driven systems.

A particularly compelling challenge is situated in cross-domain art translation: re-expressing a work from one medium (e.g., painting) into another (e.g., poetry or music) while preserving its meaning and affect [

5,

6,

7]. Unlike single-modality generation, this task must bridge fundamentally different representational primitives (pixels, notes, words) and aesthetic norms, making generic one-to-one mappings insufficient.

Historically, humans have engaged in cross-domain translation through different practices. Ekphrasis dwells on the vivid description of visual art in poetry [

8]. Synaesthesia provides analogies between sound and color, as famously explored by Kandinsky [

9]. Other examples include Scriabin’s “color organ” [

10], Wagner’s conception of the Gesamtkunstwerk [

11] (total work of art), and modern multimedia installations that blend cinematography, music, and poetry. Such practices illustrate the long-standing intuition that artistic ideas transcend individual mediums and can be reinterpreted across modalities.

Despite these precedents, systematically translating between art forms remains an open challenge. Each domain has its own symbolic language (color and composition in painting, melody and harmony in music, metaphor and narrative in literature) and the process of mapping across them is inherently interpretive.

Cognitive science has shown that cross-modal correspondences exist. For instance, higher pitched sounds are often associated with color brightness or upward motion, but these tendencies are probabilistic, not deterministic [

12,

13,

14]. As a result, computational methods cannot rely solely on surface mappings.

Conventional deep learning approaches often treat the problem as a direct mapping task, training networks to transform features in one modality into another. While such models can produce outputs that are aesthetically plausible, their black-box nature frequently results in semantic drift, where the generated piece resembles the target medium but fails to preserve the themes, emotions, or motifs of the source [

15].

For applications in art, education, and accessibility, this limitation is critical. A painting-to-music system for visually impaired users, for example, must convey not just sound but the essence of the visual work [

16]. Similarly, in pedagogy, cross-modal translations can serve as powerful tools for teaching creativity and interdisciplinary thinking, but only if they maintain conceptual fidelity [

17]. These challenges highlight the need for semantic control, transparency, and interpretability in cross-modal creative systems.

To address this gap, we introduce a novel ontology-driven multi-agent system (MAS) for cross-domain art translation. The core idea is to represent artworks within an ontology that encodes general artistic concepts (mood, motif, style) and domain-specific features (color and shape in visual art, tempo and harmony in music, imagery and meter in poetry). This ontology functions as a machine-interpretable “interlingua”, enabling consistent reasoning and alignment across modalities. The system is designed as a team of specialized agents—Perceptor, Translator, Generator, Curator, and Reasoner, operating in sequence. The Perceptor analyzes the source work; the Translator maps its features into the ontology; the Generator produces the corresponding expression in the target medium; and the Curator evaluates, and if necessary, requests refinements. The Reasoner provides deductive support and ensures coherence. Through this design, the workflow mirrors human creative practice while maintaining traceability of each decision to ontology-based justifications.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- ●

Cross-Domain Art Ontology: We introduce a cross-domain ontology encompassing interconnected concepts across visual, musical, and literary domains, with explicit correspondences for motifs, emotions, and styles. We refer to it as CDAO.

- ●

Multi-Agent Creative Architecture: We design a modular and expandable MAS where specialized agents perform perception, reasoning, translation, generation, and curation, enabling controllable and interpretable translations.

- ●

Prototype Implementation: We present a proof-of-concept system for cross-domain translation between painting and poetry. It combines state-of-the-art generative models with an ontology-driven knowledge base, implemented using the LangChain/LangGraph framework.

- ●

Evaluation and case studies: We propose mixed-method evaluation, combining case study semantic recall metrics, lay user study (N = 30; 150 evaluations), and expert reviews.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations of art translation, multi-agent systems, ontologies and related work.

Section 3 outlines the methodology, including ontology construction and MAS design.

Section 4 presents the prototype implementation.

Section 5 reports case studies and evaluation results.

Section 6 and

Section 7 discuss the implications, limitations and directions for future research. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Our work builds upon and contributes to multiple areas of research: (i) multi-modal and cross-domain generation, (ii) multi-agent systems for artificial intelligence and creative tasks, and (iii) ontology and knowledge-based approaches in computational art. We briefly review key recent work in each of these domains and outline how they inform our approach.

2.1. Multi-Modal Generative Models and Cross-Domain Translation

Multi-modal generative models are designed to handle more than one type of data (text, image, audio, video, etc.) and often aim to generate one modality conditioned on another. The state-of-the-art has rapidly advanced from single-modal generation to increasingly complex multi-modal tasks.

Early successes such as DALL-E and CLIP enabled high-quality text-to-image synthesis and cross-modal retrieval [

18,

19,

20]. Building on this, diffusion models, such as Stable Diffusion, have become a de facto standard for image generation, while their flexible architecture has been adapted for other modalities including audio [

21,

22].

Wang et al. provide a comprehensive example of a tri-modal diffusion framework, where a single model can generate text, image, and audio outputs in a coherent fashion [

20]. A key innovation in their framework is a Hierarchical Cross-modal Alignment Network that learns unified representations for concepts while still allowing each modality its specific expression.

For direct cross-domain art translation, specific tasks have been tackled in the recent literature. There are different attempts at generating music from images by mapping image features to a pretrained GAN for music [

23]. However, it was limited to simple images (like shapes or colors indicating instruments) and did not scale to complex art.

Art2Mus improved on this by incorporating more complex artwork features and using a modern diffusion-based audio generator [

24]. They used the ImageBind model to create embeddings that link images and audio, effectively creating a large paired dataset.

The work of Cao et al. is notable in focusing on a domain-specific cross-modal translation—Chinese-style videos to traditional Chinese music [

22]. By using latent diffusion models conditioned on video features and by integrating Diffusion Transformer architectures, they could maintain synchronization and thematic consistency between video and generated music. One interesting aspect of their results is the emphasis on cultural style fidelity.

The system had to “understand” the aesthetic of Chinese opera or folk melodies and reflect that in the music, which goes beyond generic emotion mapping. This points to a need for domain knowledge—motivating our use of an ontology that can encode culturally specific mappings (e.g., what musical scales or instruments correspond to certain visual motifs in Chinese art).

Conversely, generating images or animations from music has seen progress too. Recent approaches often rely on generating a sequence of visuals (frames) that correspond to an audio input. Diffusion models conditioned on audio spectrograms can create abstract visualizations that follow the music’s intensity and rhythm [

25].

There is also creative work such as cross-modal style transfer where the “style” of a piece of music (say the mood of a song) is transferred onto an image content (e.g., a photograph rendered with the emotional tone of the song) [

26].

Huang et al. [

27] introduced a method to extract a “style embedding” from music and use it to modulate an image-generating network, achieving results where, for instance, a painting of a landscape appears calm or stormy depending on whether the music was a soothing or a thunderous symphony.

Poetry-to-image or music-to-poetry translations are less studied but some efforts exist. For example, text-to-image models have been used to generate illustrations for novels or poems [

28]. There have been attempts at the reverse (image to poetic captioning) where an image is described not just factually but artfully (with metaphors, emotional language), essentially translating a visual scene into a piece of creative writing [

29]. These can be seen as a kind of art translation too.

To summarize related work in multi-modal generation: current deep learning models can achieve cross-domain generation but primarily rely on massive data and often treat the problem as one of correlation rather than understanding.

The novelty of our approach in this context is introducing an explicit understanding layer via ontology and using a modular agent approach, as opposed to a giant end-to-end model. This is complementary to these works: one could imagine future systems that integrate both learned alignments (like cross-modal embeddings) and symbolic knowledge (like ontologies) for even more robust translation.

2.2. Multi-Agent Systems and Generative Collaboration

Using multiple agents that communicate and work together has been a growing trend in AI, especially with the rise in LLMs that can serve as fluent “communicators” between agents. The rationale is that for complex tasks, breaking the problem into parts handled by specialized agents can be more effective and interpretable than a monolithic model.

Intelligent agent frameworks from the 1990s and 2000s (e.g., the blackboard system, subsumption architectures) established that agents could solve problems through cooperation, but those were often rule-based agents [

30].

Today, with LLMs and learning-based tools, a new paradigm has emerged—each agent might be powered by an LLM (or other AI model) and the system’s logic emerges from their interactions [

31].

A notable work is Generative Agents by Park et al. [

32], which demonstrated believable simulations of multiple agents (each an LLM) living in a sandbox environment and interacting, mirroring characters in a game or a small society. While not about art, it showcased that multiple LLM agents can produce coherent, emergent behavior via dialog. In essence, they can “reach an understanding” or coordinate.

Inspired by this, several frameworks have been developed to facilitate building MAS with LLMs. For instance, HuggingGPT [

33] allows an LLM to orchestrate a set of expert AI models (for vision, speech, etc.) by generating plans and interpreting results.

AutoGPT and BabyAGI popularized the idea of an autonomous agent that can spin off sub-agents to handle subtasks, using natural language for planning and tool use [

34]. These were early-stage and somewhat brittle, but they introduced the idea that complex goals can be approached by a team of AI agents self-organizing their efforts.

Chen et al. (2025) survey LLM-based MAS and categorize their applications into solving complex tasks (like coding or multi-step reasoning), simulating scenarios (like social interactions or negotiations), and even evaluating generative agents by having them interact [

35].

A recurring observation is that communication is key. Agents need protocols or shared memory to exchange information effectively. Some works, such as SMART-LLM [

36], use an LLM to decompose tasks and assign roles to other agents, a strategy we also employ in having a Reasoner agent as supervisor.

Others explore fully distributed decision making with multiple LLMs working in parallel and negotiating their outputs. For example, one approach gave each agent its own GPT-4 and let them ask each other for information or help, leading to better coverage of partial knowledge [

37].

In the context of creative tasks, Luo’s MASC is directly relevant [

38]. MASC’s architecture (Task Agent, Domain Analysis Agent, Deepthink Module, Generator Module, Reflection Module) maps closely to our Reasoner, Perceptor, Translator (ontology query), Generator, and Curator agents. The success of MASC with diffusion models and LLMs for image and text generation validates our hypothesis that an agent-based approach can handle the complexity of creativity better than a single model.

Additionally, Imasato et al. provide evidence that a multi-agent setup (even if the agents are simulated artists) can produce more creative diversity and quality [

39]. In their experiments, they had multiple “virtual artists” (LLM-driven image generators) that could critique each other’s work and iterate, which led to art that human judges found more creative. We incorporate a similar notion of critique and refinement via the Curator agent.

Another relevant MAS is CrossMatAgent [

40]. It combined LLMs with diffusion models in a hierarchical team to design complex materials, which is analogous to combining reasoning and generative capabilities. Their design had specialized agents for pattern analysis, prompt engineering, and a “supervisor” agent, orchestrated by GPT-4, to ensure the generative outputs meet certain design criteria. The demonstrated outcome was an automated design process that could produce valid, diverse designs that were ready for simulation and fabrication. We take inspiration from this by ensuring our system is not just generative but also evaluative—checking that the generated art meets conceptual criteria.

CrossMatAgent’s success in a highly technical creative task hints that even in artistic translation, a disciplined multi-agent approach could enforce constraints and goals.

Recent developments in multimodal artificial intelligence have revisited the fundamental architectural trade-offs between monolithic, compositional, and agentic system designs.

Monolithic multimodal models, such as Mono-InternVL-1.5 [

41], demonstrate that unified networks can efficiently integrate multiple modalities within a shared representational space, reducing inference cost while maintaining cross-modal alignment.

In contrast, Du et al. advocate modularity through the composition of specialized generative components, emphasizing the advantages of semantic abstraction and domain-specific reasoning [

42].

At the same time, reasoning-centric frameworks such as Multimodal Chain-of-Thought [

43] extend compositionality into the cognitive domain, integrating visual and linguistic reasoning through staged inference processes. These systems illustrate how hierarchical reasoning can enhance interpretability, yet they continue to rely heavily on sequential LLM orchestration for coordination.

From a different perspective, the TB-CSPN Architecture for Agentic AI [

44] advances an explicitly agentic paradigm, replacing prompt-chained pipelines with a verifiable coordination substrate based on Colored Petri Nets. By decoupling semantic reasoning from coordination logic, TB-CSPN reduces dependence on LLM-mediated orchestration and enables scalable, formally grounded multi-agent collaboration.

Positioned within this continuum, the currently proposed ontology-driven multi-agent system follows the compositional philosophy yet extends it through explicit semantic grounding. Rather than relying on latent feature coupling or prompt-based coordination, it achieves agent cooperation through an ontological interlingua that ensures interpretable and reusable knowledge exchange across modalities. This design creates a hybrid system where symbolic reasoning and neural generation work together, uniting the clarity of knowledge-based methods with the adaptability of deep learning.

In summary, related work in MAS suggests that: (a) LLMs are effective coordinators and communicators for agents, (b) multi-agent setups can handle tasks requiring multiple expertise (analysis, creation, evaluation) and (c) iterative feedback loops among agents can improve outcomes.

Our system builds on these principles and is among the first, to our knowledge, to apply an LLM-based multi-agent framework to cross-domain artistic creativity. We contribute to this area by showing how an explicit knowledge structure can be integrated into the agent loop and how agents can use it as a common ground for communication (much like human team members relying on a shared terminology or theory when collaborating on art).

2.3. Ontologies and Knowledge-Driven AI in the Arts

Ontologies have been used in AI for decades to model domains ranging from medicine to geography. In the context of art and creativity, ontologies are less common, but there are notable efforts to encode artistic knowledge.

For instance, the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus [

45] and similar knowledge bases provide hierarchical vocabularies of art styles, movements, materials, etc., which is used by different museum information systems.

In research, some have proposed ontologies of music theory or narrative theory to help AI systems understand those domains. One example is the work by García et al. [

46] where they created an art-specific graph linking paintings to attributes (artist, school, genre, iconography) and used it for cross-modal retrieval. By querying this graph, an AI system could find paintings related to a concept or even suggest analogies (like “find me Baroque paintings related to the theme of X that might match this Baroque music piece”).

Another example is the Music Ontology project [

47] which structured concepts like artist, album, genre, but also included some musicological terms. While that ontology was more for organizing collections, one could see its extension for creative AI (e.g., an ontology that knows “minor key” implies “sadness” in Western music, which could link to “blue color” in an art ontology).

Kokkola advances a relational ontology account of multimodal translation, arguing that relations among modes (rather than modal “essences”) ground legitimate cross-modal transfer, providing a conceptual basis for operationalizing source to target correspondences [

48].

In aesthetics and media theory, Bajohr’s “operative ekphrasis” claims contemporary multimodal AI collapses traditional text/image distinctions, thus demanding a revised notion of ekphrasis beyond mere description, closer to procedural translation [

49]. Verdicchio contrasts prompt engineering with ekphrasis, articulating norms for when cross-modal rendering counts as interpretive translation rather than instruction-following [

50].

In AI-driven multimedia, knowledge graphs have been shown to improve interpretation tasks. For image captioning, having a knowledge base of common sense or factual info can help the captioning model not just describe “a man holding a guitar” but add “the man appears to be a rock musician performing on stage” if it recognizes the context [

47]. For art, which is rich in context, a knowledge base can similarly provide that extra layer. In artwork captioning, as mentioned, incorporating metadata and art historical context via a graph led to captions that understood style and context (e.g., recognizing that a painting with certain features is from the Impressionist period and reflecting that in the description) [

51,

52].

This motivates our use of an ontology for art translation. By consulting an ontology, systems can gain a form of “cultural and aesthetic awareness” that a purely learned model might lack.

Tabaza et al. [

53] created an ontology to bind text, images, graphs, and audio for music representation learning. They used Protégé to define classes representing music concepts and linked them to other modality representations, enabling a model to learn joint representations [

54].

Another relevant domain is affective computing: ontologies of emotion (like WordNet-Affect or others) can be used to ensure an AI’s outputs hit a certain emotional target [

55]. Our ontology indeed borrows from affective models by including emotional descriptors and their cross-modal expressions.

Knowledge-driven approaches also coincide with the concept of symbolic AI meeting generative AI. There is emerging research on using LLMs to assist ontology engineering or vice versa [

56]. For instance, large models can help populate a knowledge graph or check consistency and a knowledge graph can provide facts to an LLM for more accurate generation.

In our prototype, we leverage the LLM agent to query the ontology and interpret its results in natural language terms, effectively translating between symbolic knowledge and creative decisions. This synergy reflects a broader trend of neuro-symbolic AI, bringing together reasoning (symbolic) and data-driven intuition (neural networks). Our contribution is an applied instance of this in the creative domain.

Prior agentic systems for creative tasks coordinate LLMs and generators but typically lack an explicit semantic interlingua. For example, frameworks that orchestrate analysis–generation–reflection agents improve quality via iteration, yet rely on latent embeddings or prompts for alignment. In contrast, our MAS anchors agent dialog and decisions in CDAO, enabling typed correspondence links between source/target elements, reasoner-backed inferences (e.g., element-to-artwork property chains), and auditable curator checks on themes, motifs, and emotions. Empirically, this yields measurably higher descriptor preservation than prompt-only baselines in our painting ↔ poetry setting.

To sum up, our work is related to and builds upon: (i) multi-modal generation research by adding structured alignment, (ii) multi-agent AI by adopting an LLM-coordinated team for a creative task, and (iii) knowledge-based AI in art by formalizing cross-domain aesthetics into an ontology.

By combining these, we aim to set a new direction for intelligent creative agents that are not only data-driven but also knowledge-guided and capable of sophisticated collaboration, thereby pushing the envelope of what AI can achieve in translating and transforming art.

3. Methodology

We address cross-modal art translation with a process as follows: given a source artwork (painting/image, music/audio or poem/text), produce a target-modality artwork that preserves the source’s salient content (relations, affect, style) and provide explanation how this preservation was achieved. Preservation is defined with respect to a shared semantic model, which provides a common vocabulary of artistic elements and descriptors.

Therefore, our approach consists of two tightly integrated components: (1) a cross-domain art ontology that represents knowledge about visual, musical, and poetic concepts and (2) a multi-agent system that uses this ontology as a shared knowledge base to carry out the translation process.

3.1. Ontology for Cross-Domain Art

The proposed ontology serves as a conceptual bridge between art forms. Its initial scope spans painting, poetry, and music, selected for their distinct sensory modalities (vision, language, hearing) and rich theoretical foundations. The design is extensible, allowing future inclusion of domains such as film, sculpture, dance, and others.

The Cross-Domain Art Ontology (CDAO) is implemented in Protégé (OWL 2 RL). It follows established ontology principles—modularity, reusability, and reasoning tractability, extending best practices to represent the affective, semantic, and aesthetic dimensions of artworks.

CDAO supports cross-modal translation by (i) representing artworks and their artistic elements in each modality, (ii) describing their affective (emotion), semantic (motif, theme) and aesthetic (style) facets, while (iii) enabling inference that lifts low-level features to high-level meanings.

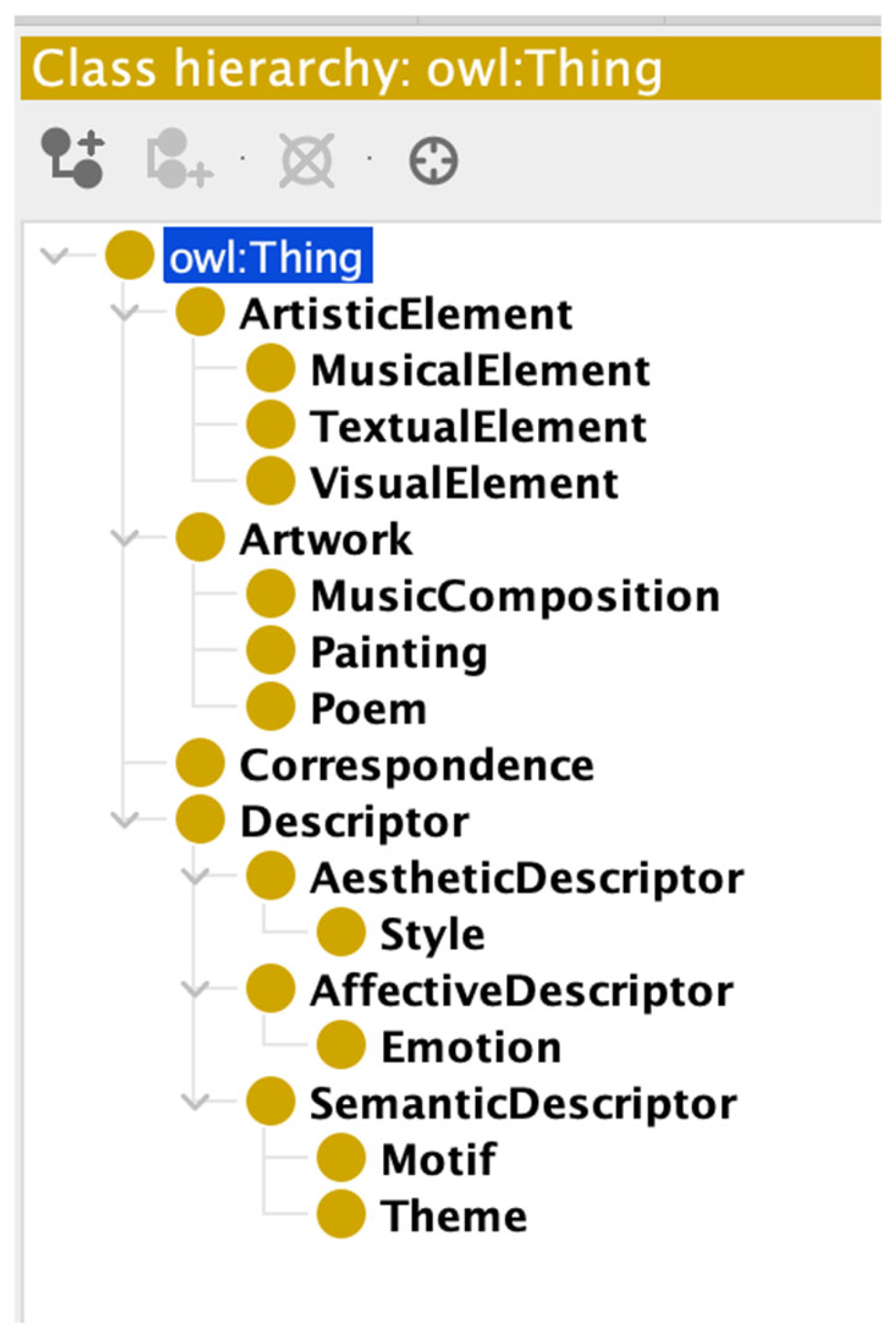

CDAO provides a formal schema for representing artworks across modalities (visual, textual, musical) and their high-level semantics. As visualised in

Figure 1, t defines a small taxonomy of core classes: Artwork is the superclass for any art piece, with domain-specific subclasses Painting, Poem, and MusicComposition.

Each artwork is composed of ArtisticElement instances (with sub-classes VisualElement, TextualElement, MusicalElement) representing constituent components or features within the piece (e.g., a shape or color patch in a painting, a metaphor or line in a poem, a motif in music).

This part-whole structure (artwork → elements) is captured via the object property hasElement, with domain Artwork and range ArtisticElement.

3.1.1. Cross-Domain Descriptors

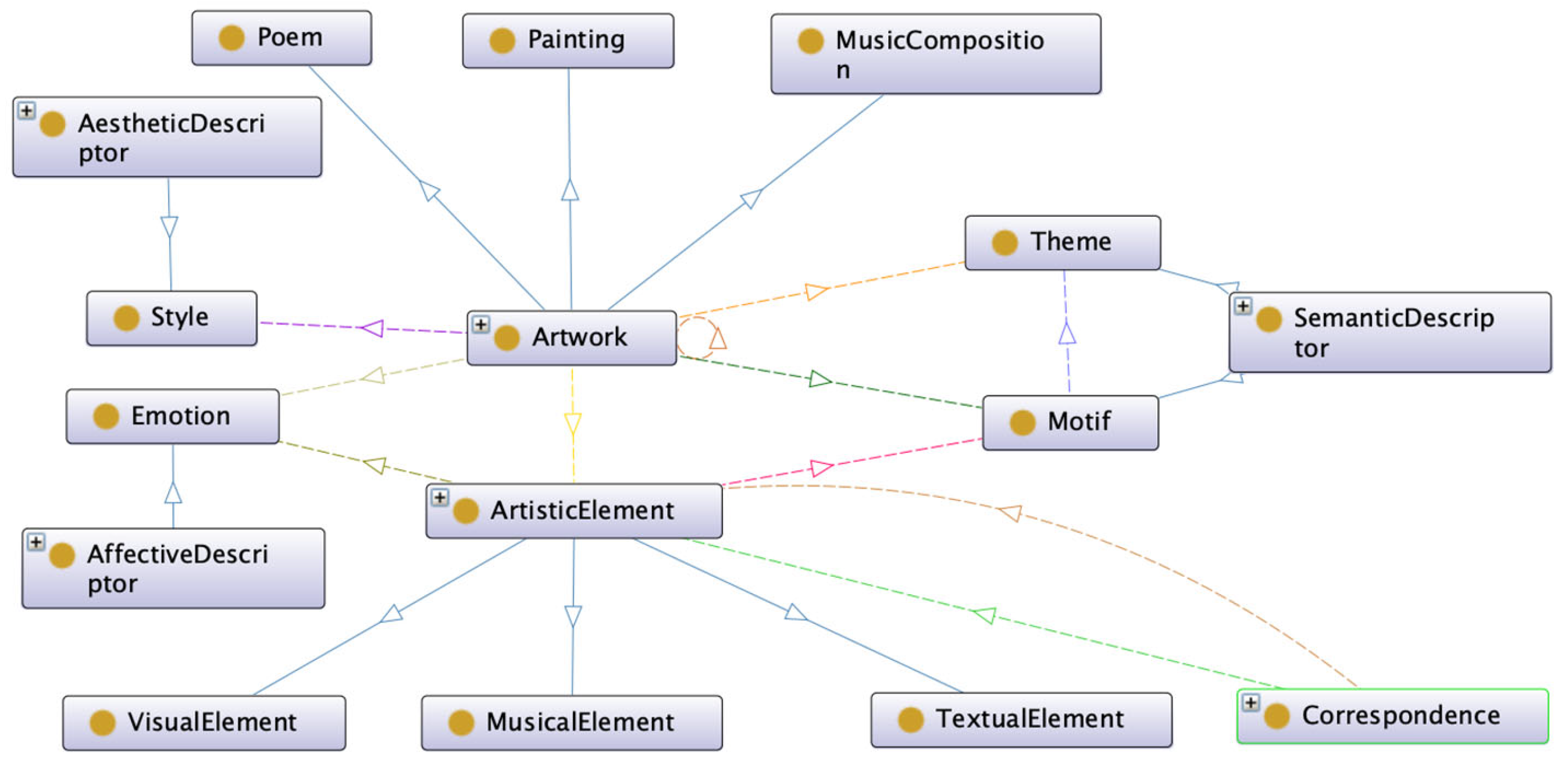

To achieve semantic alignment across different art forms, as presented in

Figure 2, CDAO introduces descriptor classes that abstract content and style in modality-independent terms. All descriptors inherit from a generic Descriptor class, partitioned into three facets: SemanticDescriptor, AestheticDescriptor, and AffectiveDescriptor.

Under these, CDAO defines:

Theme and Motif—subclasses of SemanticDescriptor representing the subject matter or recurring conceptual patterns in art. A Theme is a high-level semantic meaning or abstract idea that an artwork conveys (e.g., nature’s solitude). A Motif is a more concrete, recurring element or symbol that expresses or supports that theme (e.g., sun, waves).

Style—a subclass of AestheticDescriptor representing the stylistic genre or artistic technique (e.g., Impressionism, Haiku, Baroque-style music). In CDAO’s core, Style is kept abstract. It can be linked to an external vocabulary for concrete style labels (e.g., SKOS [

53]).

Emotion—a subclass of AffectiveDescriptor representing the emotional tone or response associated with the artwork (e.g., happiness, serenity). CDAO uses Emotion to capture affective semantics.

These descriptors serve as cross-domain semantic bridges. Regardless of modality, an artwork can be described by a theme, motif, style, and evoked emotion.

This enables alignment of a painting, a poem, or any other artwork, if they share semantic or affective descriptors. An artwork can directly link to these descriptors via properties like hasTheme, hasMotif, hasStyle and expresses (for emotions). In the ontology, hasTheme and hasMotif apply to Artwork linking to a Theme or Motif, while expresses links an Artwork to an Emotion.

3.1.2. Correspondence Mapping (N-Ary)

CDAO formalizes cross-domain relationships through the class Correspondence, which encodes mappings between a source and target element via the properties sourceElement and targetElement.

Each correspondence is typed by mappingType (e.g., Literal, Analogical, Affective), with predefined instances enabling semantic annotation. A quantitative confidence property (decimal range) further qualifies the mapping. This design captures not only what elements align, but how and with what certainty. At the artwork level, the property inspiredBy (domain/range: Artwork) records source–target relationships, such as a poem derived from a painting. Overall, CDAO’s modular structure separates artworks and their constituents from descriptors and mappings, providing a rigorous semantic backbone for cross-domain alignment.

3.1.3. Property Chain Axioms

CDAO uses the OWL object property composition to automatically derive high-level relationships from lower-level ones. Specifically, it defines chain axioms that lift element-level annotations up to the artwork level.

For example, if an artwork A hasElement E and that element E elementExpresses an emotion X, the ontology can infer that artwork A expresses emotion X. This is captured by the chain: hasElement ∘ elementExpresses ⊑ expresses (meaning an artwork connected via hasElement then elementExpresses implies an expresses relationship).

Similarly, CDAO links motifs to themes with a two-step chain:

- -

if artwork A hasElement E and E elementRealizesMotif M, then A hasMotif M (hasElement ∘ elementRealizesMotif ⊑ hasMotif).

- -

if artwork A hasMotif M and M motifSuggests Theme T, then A hasTheme T (hasMotif ∘ motifSuggests ⊑ hasTheme).

3.1.4. Interoperability with Established Standards

The ontology is extended with lightweight alignments to established vocabularies, ensuring interoperability while preserving its internal semantic structure. Artistic styles, motifs, and themes are connected to the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus through SKOS mappings [

57], enabling direct reuse of standard cultural heritage identifiers [

45]. High-level classes such as Artwork, Painting, Poem, and MusicComposition are aligned with CIDOC-CRM and provenance is harmonized with PROV by treating inspiredBy as a form of derivation [

58]. Musical works are integrated with the Music Ontology [

47], while emotional descriptors are linked to external lexicons such as WordNet-Affect [

59] and EmotionML [

60]. These extensions leave the core taxonomy and property-chain axioms unchanged, so existing OWL 2 RL reasoning remains valid. Validation rules allow artworks to reference either native ontology individuals or external identifiers, enabling agents to seamlessly operate across both. As a result, the ontology functions not only as an internal interlingua for art translation but also as a bridge to the wider linked-data ecosystem.

In summary, the ontology is the semantic heart of our methodology. It ensures that all agents, regardless of their specialization, refer to a shared conceptualization of art [

61]. With the ontology in place, we turn to the multi-agent system that operates on this knowledge representation.

3.2. Multi-Agent System Architecture

The multi-agent system is designed to modularize the translation process and leverage specialized capabilities while maintaining overall coherence through the ontology.

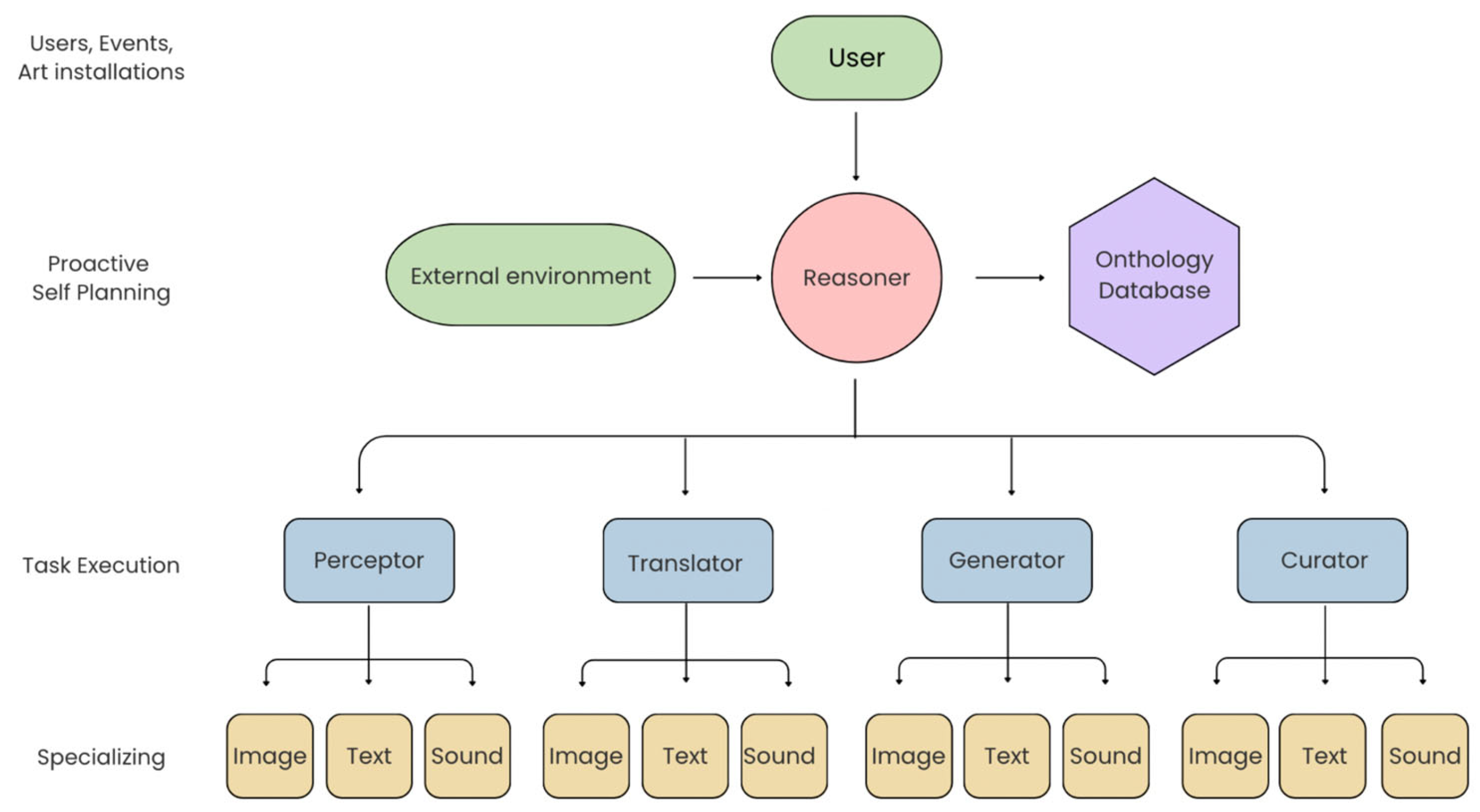

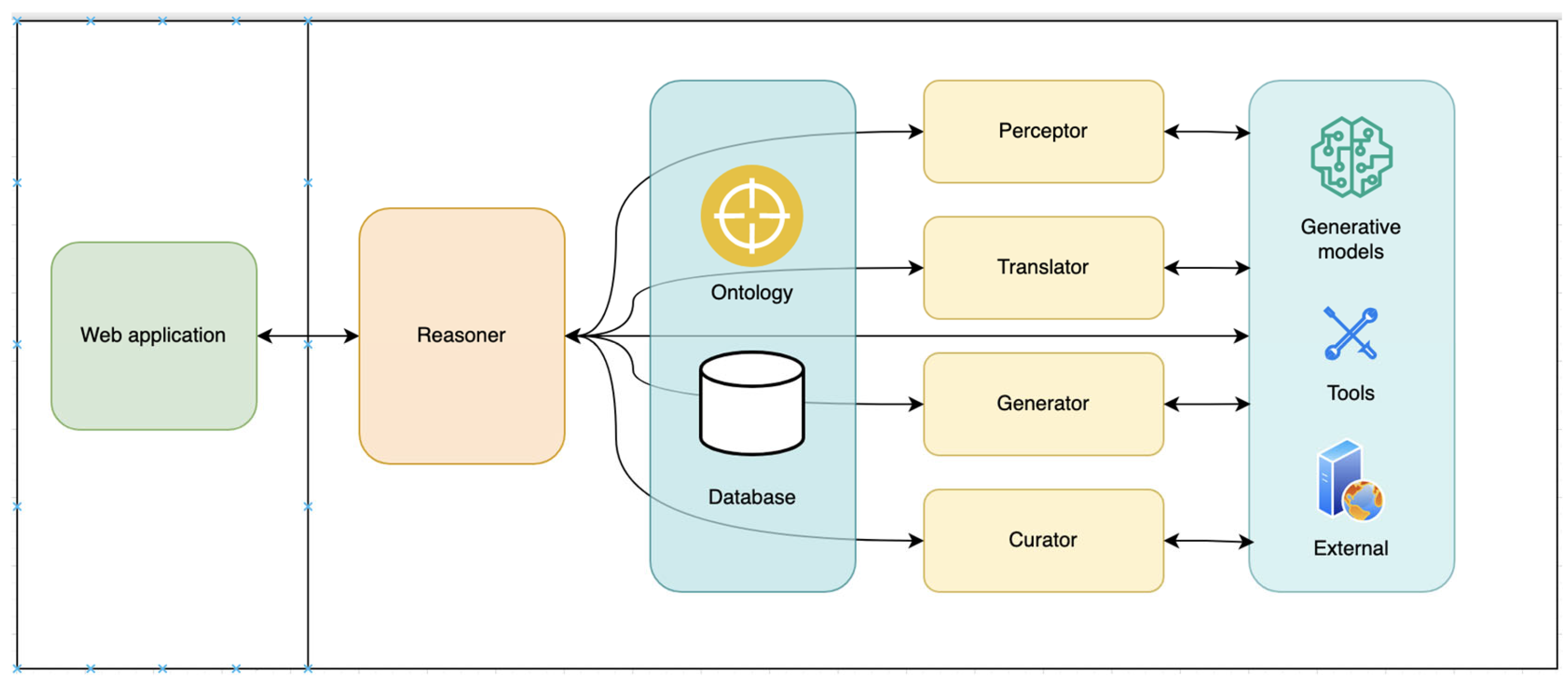

It consists of a number of agents, each with a specific role, communicating to complete the process of art translation from one domain to another. As presented in

Figure 3, the architecture is hierarchical/multi-level and can be expanded on specific use-cases. Specifically, deeper levels can allow for the inclusion of specified agents (e.g., specialized painting and graphic perceptors or specific art style generators and curators).

Experiments with hybrid and peer-to-peer communication strategies yielded suboptimal results, primarily due to constraints in context size management. Accordingly, a hierarchical approach was adopted, as it offers greater robustness for maintaining the integrity of the art translation task and is better aligned with the capabilities of current models and available computational resources [

62].

This way the agents, concentrated on only one task, have the right context and the possibility of communication override and hallucinations is contained. Different communication protocols can be applied, such as Agent2Agent [

63], but for our PoC, we are leveraging LLMs for each agent and using predefined instructions and communication in natural language in combination with a blackboard.

3.2.1. Agent Roles

The system comprises five principal agents, presented in

Figure 4, each encapsulating specific functionalities:

Reasoner: Coordinates the workflow. It receives the user input (artwork—poem, image, music) and the translation direction, then triggers each agent in sequence. It routes data between agents, adjusts flow when needed, and acts as a “supervisor” or “art director”.

Perceptor (Analysis and Annotation): Analyzes the raw input artworks (image, text, audio) and extracts structured descriptors—concepts, themes, emotions, style. Modality-specific methods are used: NLP/LLMs for text, CV models for images, audio analysis for music. Additional tools can also be used, such as external APIs (e.g., text/image/audio search). Features are represented in the ontology as ArtisticElement subclasses (e.g., SfumatoBlending, OceanicImagery). The Perceptor asserts ontology relations (e.g., elementRealizesMotif, elementExpresses) and produces both semantic graphs and supporting raw analysis. It may perform iterative enrichment using external sources if input is insufficient.

Translator (Conceptual Mapping and Planning): Transforms the Perceptor output into an intermediate representation aligned with the ontology and tailored to the target modality. This often takes the form of a structured prompt or plan. The Translator uses Correspondence instances linking source and target ArtisticElements with a defined mappingType. Ontology guidance ensures consistent cross-domain mappings (e.g., cosmic longing → celestial imagery; Impressionist painting → sensory-rich poem).

Generator (Modality Synthesis): Produces the final artifact (poem, painting, music) based on the Translator’s structured plan. It interfaces with generative models: LLMs for poems, diffusion models for paintings, audio models for music. The Generator is modular, allowing different models per modality.

Curator (Semantic Alignment Verification): Evaluates the generated output against the input through analysis. After an artifact is generated, it is analyzed via the Perceptor. Then the Curator uses both input/output analyses, compares descriptors, and uses ontology reasoning to measure overlap. Shared references to Theme, Motif, and Emotion individuals allow for precise alignment checks (e.g., a “happy poem” aligns with a “joyful image”). The Curator may score alignment, generate critique, or trigger iterative refinement, via the Perceptor, Translator, or Generator.

3.2.2. Communication and Memory

The agents exchange information via a hierarchical controller (Reasoner) and a shared state (“blackboard”). The Perceptor can write both structured RDF assertions into the CDAO graph (e.g., hasElement, elementExpresses, hasTheme) and compact summaries to the blackboard. The Translator queries the ontology to produce a target-modality plan (descriptor set and correspondence instances). The Generator consumes this plan; the Curator re-analyzes the output and compares descriptors against the source using the ontology’s property-chain inferences. Natural-language notes are logged for traceability, but decisions bind to ontology URIs, improving reproducibility and limiting LLM hallucination.

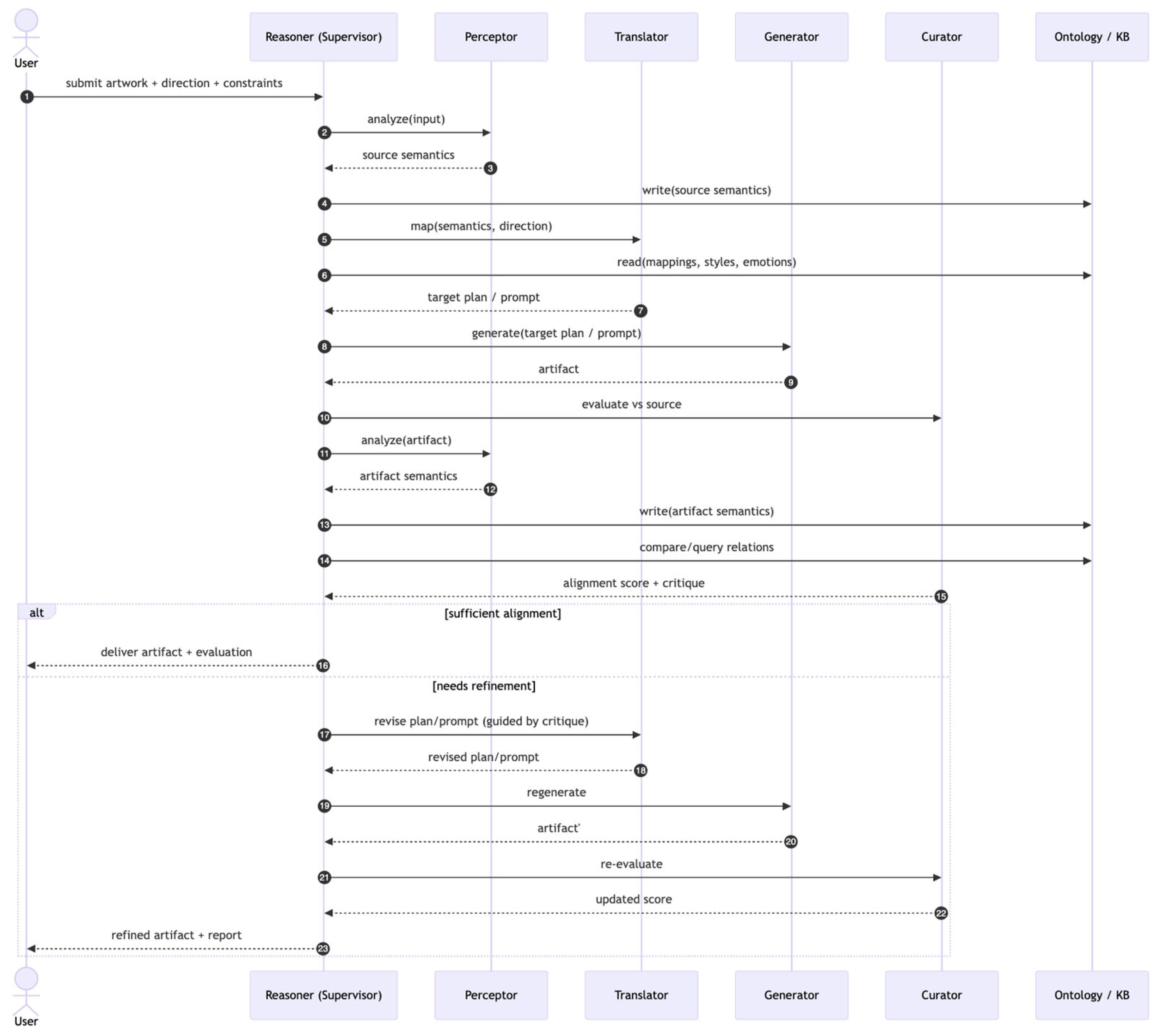

3.2.3. Example Flow

The interactions are coordinated by the Reasoner agent, which essentially runs an iterative loop:

Input ingestion: The system receives the source artwork.

Perception: Analyses input. The Perceptor’s findings (aligned with ontology terms) are added to the knowledge base.

Translation planning: The Translator reads the ontology state (populated with source descriptors) and writes a set of target-domain descriptors and high-level plan for the new artwork.

Generation: Produces the new artwork. The Generator uses the Translator’s plan to guide a generative model and outputs the raw artifact (image, audio, or text).

Curation: Evaluates the translation. The Curator compares the output against the source’s ontology description (and possibly style guidelines) and decides if the output is acceptable or needs refinement.

Refinement loop: If refinement is needed, the Curator’s feedback (in ontology or textual form) is fed back through the system; the Reasoner may loop back to either the Perceptor, Translator, or Generator with additional constraints or adjustments. This loop can repeat.

Final output: Once the Curator approves, the final output is produced, along with an explanation compiled from the ontology and agent decisions.

3.2.4. Example CDAO Processing

Suppose a painting contains a crimson dusk sky (VisualElement) that the Perceptor annotates with elementExpresses = melancholy and elementRealizesMotif = twilight. By the chain hasElement ∘ elementExpresses ⊑ expresses, the artwork inherits expresses = melancholy. An agent queries CDAO for cross-modal links and retrieves that twilight suggests the Theme = impermanence and that melancholy licenses poetic imagery such as “embers of day” and meter with low arousal. It then instantiates a Correspondence individual tying the visual element to a TextualElement plan (lexical field {twilight, embers, hush}, line breaks, soft cadence). The Generator realizes this plan as verse and the Curator re-perceives the poem, verifying hasTheme = impermanence and expresses = melancholy match the source.

3.2.5. Cognitive and Affective Traits

The evaluative and reasoning capacities embedded in the Curator and Reasoner agents draw conceptually on the tradition of computational creativity systems that aimed to simulate higher-level cognitive and affective traits in artificial artists. Pioneering work by Colton and Wiggins [

64] demonstrated that creative autonomy emerges when a system can not only generate artifacts but also assess its own outputs against internalized aesthetic or conceptual criteria. Following this rationale, our methodology incorporates an explicit evaluative loop: the Curator agent performs self-assessment of outputs with ontology-based criteria, while the Reasoner can mediate reflective refinement and justification. This design situates the proposed architecture within the broader evolution of self-reflective, autonomy-oriented creative systems, ensuring that evaluation and interpretation are intrinsic components of the generative process rather than external afterthoughts.

3.2.6. Foundational Taxonomy of Creativity

From a theoretical perspective, the proposed approach resonates with Boden’s foundational taxonomy of creativity, which distinguishes between combinational, exploratory, and transformational forms of creative cognition [

65]. Within this framework, the current system can be understood as a hybrid system that operationalizes all three forms through multi-agent mediation. Combinational creativity is realized in the model’s capacity to associate symbolic and perceptual features across artistic domains. Exploratory creativity emerges from the system’s navigation of ontologically structured aesthetic spaces. Then transformational creativity arises when the agents collaboratively reconfigure the representational parameters of a domain, leading to novel cross-domain expressions. In this way, the present work extends Boden’s paradigm by embedding the creative process within a distributed architecture, where symbolic reasoning and generative production interact dynamically.

3.2.7. Summary

By clearly separating the concerns into analysis, semantic translation, generation, and evaluation, we achieve modularity (each agent can be improved or replaced independently) and transparency (we can inspect the intermediate ontology-based representation to see what the system believes is important about the art).

This directly addresses a central criticism of deep generative models: their lack of interpretability. Here, if the final poem is unsatisfactory, through reasoning, we can pinpoint whether it was the analysis stage missing something or perhaps an ontology mapping that was incomplete, rather than just having a single inscrutable model.

Taking advantage of the hierarchical approach, multi-turn interactions can be considered if the user is in the loop. Because all the data passes through the Reasoner, the user can easily follow the process. For example, he might say “You are missing parts of the translation” or “I like this music you generated from my painting, but can you make it a bit more upbeat without losing the essence?”. The system can then treat that as a new constraint and the Translator agent will adjust the plan, consulting the ontology or an LLM for what “more upbeat” could translate to without flipping mood entirely.

Our methodology essentially hybridizes symbolic AI and neural AI in an agent framework. In the next section, we describe how we implemented this concept in a prototype system and provide an example of it in action.

The proposed multi-agent system exhibits several advantages in terms of modularity, explainability, adaptability, and robustness. Its modular architecture enables independent improvement of individual agents, such as upgrading the Perceptor with a more advanced analysis algorithm without affecting the Translator or Generator, provided the outputs remain ontology-compatible. Explainability is supported through ontology-based, human-readable outputs that allow transparent tracing of system decisions and mappings. The framework further demonstrates adaptability, as it can be extended to new artistic domains by incorporating additional ontology modules and agents without requiring redesign of the pipeline. Finally, robustness is achieved through built-in fault tolerance and corrective feedback, whereby errors or omissions in one component can be detected and compensated by others, thus ensuring reliable performance in art translation tasks.

4. Implementation

To validate our approach, we developed a prototype Proof-of-Concept system that implements the ontology-driven MAS for art translation. The prototype is deployed as a web-based application where users can submit an artwork (painting or poem) and request a translation to the other modality. Here we outline the technical components of the implementation including the multi-agent orchestration, the knowledge base infrastructure, and the generative models employed.

The prototype consists of three main layers: (1) a web application (for user interaction and session management), (2) the multi-agent system (which carries out the translation logic using the agents and models), and (3) the knowledge/data layer which includes the ontology and persistent storage.

This architecture implements a clean separation of concerns: the web frontend handles user interaction and logging, while the multi-agent backend encapsulates the AI logic for cross-domain translation.

A high-level architecture diagram is shown in

Figure 5. In summary, when a user inputs a painting image into the web interface and requests a poem, the request is passed to the agent system which loads the image, calls the sequence of agents as described in

Section 3, and ultimately returns a generated poem, which the web app displays. The user can then provide feedback or evaluate the result via the interface.

Currently, the prototype is limited to two domains—poetry and painting. While an appropriate open-source model for sound generation (MusicGen [

66]) was available, no suitable open-source model for sound analysis could be identified. Data on specific musical works was obtained only through external APIs to retrieve additional information such as history, lyrics, and themes. Consequently, the extension to music as a third domain is left for future work.

4.1. Web Application

The web application, implemented with Python/Django, provides ease of access to the system for testing purposes. It has standard functionality such as authentication, profile management, and history of interaction with the system—how many translations the user has generated. This allows tracking of how the system could respond in real conditions.

The web application also has a component for evaluating the results. After finishing each art translation request, the user is prompted to provide feedback and fill a short questionnaire (Likert scale style 1–5). Another part of the application is the administration.

4.2. Multi-Agent System

4.2.1. Orchestration

We utilized the LangGraph framework to implement the agent orchestration, where each agent is a node of a graph. LangGraph is an extension of the LangChain framework enabling graph-structured LLM workflows. Each node wraps an LLM with tools (ontology query, image analysis, web search) and reads/writes a blackboard (structured state, additionally persisted in PostgreSQL). The Reasoner advances the graph based on score conditions (e.g., certain Curator scores can trigger re-translate).

A shared state or “blackboard” memory is used to hold intermediate data (such as the artwork analysis and any semantic features identified) that persists throughout the workflow. By sharing a common knowledge state, we ensure that, for example, the Translator can reference what the Perceptor extracted and the Curator can compare the final output against the original input’s features. During development phases, for testing purposes, we changed that and limited full-access for some of the agents.

The LLMs we used are locally hosted for reproducibility and data control. In our prototype, all the models used the same 12B-parameter tool-augmented model (gemma3-tools:12b), except for the Reasoner and Generator, which used an instruct model (qwen2.5-7B-Instruct-1M). For image analysis, we used a 7b-parameter multimodal model (LLava:7b) and, for image generation, a latent diffusion model (FLUX.1-schnell).

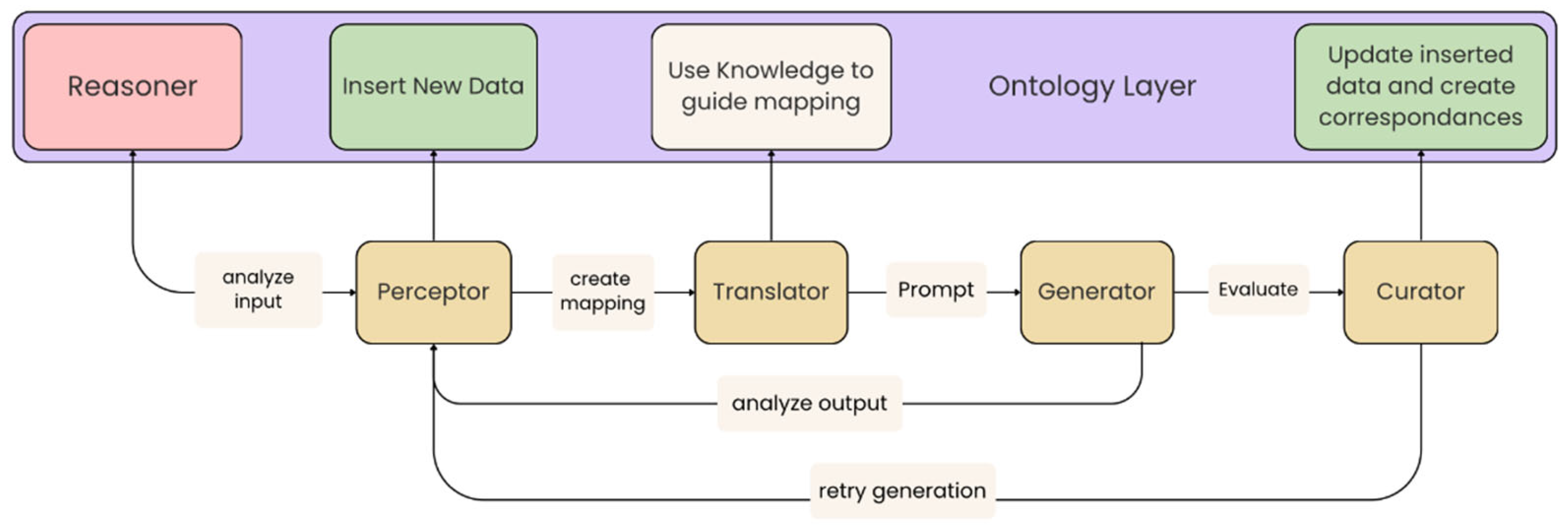

As presented in

Figure 6, Each agent’s logic is implemented as follows:

Reasoner (Supervisor): Orchestrates the overall workflow. Based on Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct-1M, it receives the user’s input (either an image or a poem) and coordinates the sequence of actions.

Perceptor (Analyser): For a painting input, the Perceptor uses a tool (workflow based on LLava:7b) to inspect the image and extract salient features (objects, scenes, colors, moods). For a poem input, another tool (workflow based on gemma3-tools:12b) is used to interpret the poem’s themes, imagery, and mood.

Then the agent produces a structured representation of the artwork, which is later inserted into the CDAO. This agent also has access to the internet and additional APIs, in case the perceivable data is not enough (e.g., find information about an artwork’s author, era, or story).

Translator (Mapper): A specialized agent that takes the Perceptor’s output (domain-specific features) and maps it to equivalent concepts in the target domain (visual ↔ poetic). The Translator queries the ontology to find correspondences between visual elements and poetic motifs. For example, if the Perceptor identified “a red sunset sky” in a painting, the Translator might map this via the ontology to “tomorrow’s hope” as a poetic concept. This ensures that the core symbolism is preserved across domains. Here we used only one LLM: gemma3-tools:12b.

Generator (Creator): This agent is based on an instruct LLM (Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct-1M) and uses tools to generate the final output from the prompt provided by the Translator.

Curator (Evaluator): The Curator agent, based on gemma3:12b, acts as a reviewer and refiner. He evaluates the output from the Generator for quality, coherence, and faithfulness to the input. The Curator provides a brief critique and rating, can optionally suggest minor improvements, and loop back for feedback.

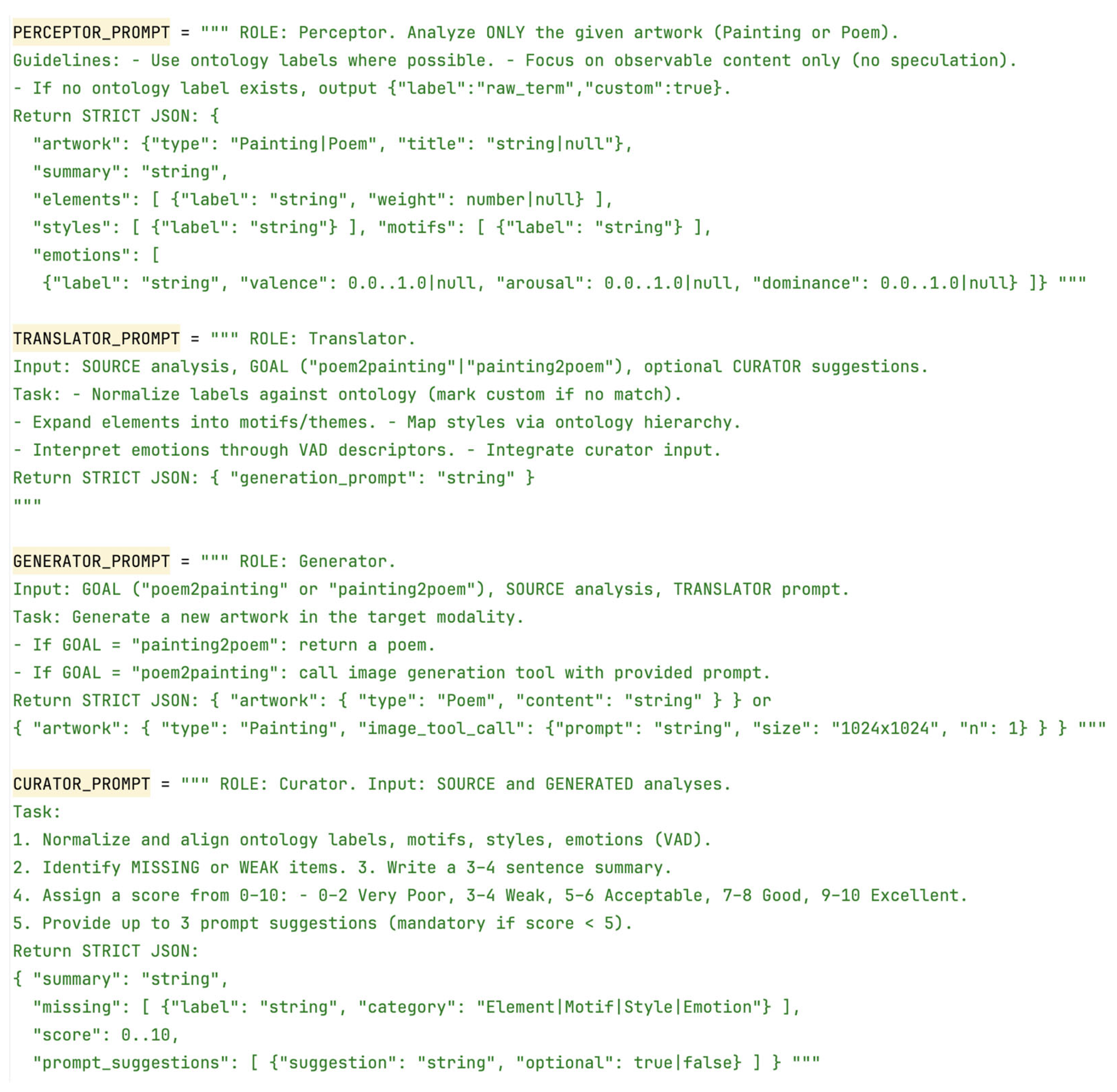

4.2.2. Prompting

Prompting is a central mechanism in our multi-agent prototype. As presented in

Figure 7, each agent—Reasoner, Perceptor, Translator, Generator and Curator—operates with a narrow function and prompts act as structured instructors that ensure continuity across modalities. Poorly designed prompts lead to hallucination, semantic drift, and tool usage issues, while well-structured ones enforce coherence and reproducibility [

67].

Prompting further mediates the balance between constraint and creativity: overly rigid prompts yield formulaic outputs, whereas underspecified ones result in inconsistency. Effective designs preserve semantic boundaries while leaving room for generative freedom, aligning with recent findings on prompt engineering and multi-agent coordination [

67].

4.3. Knowledge-Data Layer

4.3.1. Ontology

The working copy of CDAO is a Turtle RDF file defining relationships between visual concepts and poetic concepts. It acts as a cross-domain dictionary or mapping. It grounds the creative translation in established symbolic relationships. By doing so, it prevents the AI from making arbitrary or mismatched analogies. In essence, the ontology acts as a semantic bridge between the visual and poetic modalities.

Implementation uses RDFlib to maintain an RDF graph. Each Perceptor analysis triggers an upsert: new individuals are created or updated and triples are materialized. An OWL RL reasoner (owlrl.DeductiveClosure) applies ontology axioms and property chains, ensuring that higher-level inferences (e.g., artwork expresses joy if an element does) are captured. SHACL validation further enforces schema compliance. This ontology integration ensures that multimodal content is described within a common semantic layer, enabling meaningful comparison between modalities.

4.3.2. Database

A PostgreSQL database is used to also persist data at each stage—including the original artworks, extracted features, intermediate prompts, final translations, and evaluation metadata, for auditing and further analysis.

4.4. Curator Translation Score

The Curator agent provides the evaluative layer by generating a translation score through structured prompts. Instead of generic similarity checks, the curator is guided by the ontology to assess whether key elements, motifs, styles, and emotions identified in the source are preserved or meaningfully transformed in the target. The evaluation covers five main criteria: fidelity, affect congruence, style transfer, correspondence clarity, and target coherence.

Each criteria is rated on a 1–10 scale, where higher values indicate stronger alignment. This procedure ensures that the Curator’s judgments remain element-aware, ontology-grounded, and reproducible, while still adaptable to different evaluation contexts.

To summarize, by combining modern LLM orchestration techniques (LangGraph’s multi-agent supervisor) with semantic knowledge (ontology-based mappings) and a full-stack web approach, the prototype achieves a comprehensive solution for creative cross-domain art translation, within painting and poetry domains. In the next chapter, we proceed to review the results of the prototype in the form of case studies and evaluations.

5. Case Studies and Evaluation

Evaluating cross-domain art translation is inherently challenging because there is no single “ground truth” for what a correct translation is. Art is subjective and multiple diverse translations could all be valid. Therefore, we adopt a multi-perspective evaluation strategy to assess our system:

- ●

Case studies including ontology-based semantic measures of how much content is preserved through the translation process.

- ●

Quantitative human evaluation—lay user study.

- ●

Qualitative expert evaluation—painter, poet, and sculptor.

Through this triangulation, we aim to measure both the objective alignment of content and the perceived creative quality of the outputs.

5.1. Case Studies

We conducted experiments on a set of representative translation tasks focusing on painting to poem and poem to painting, currently supported by the prototype. Within these, we focused on round-trip translations (painting → poem → painting and poem → painting → poem) to test whether the content survives a full cycle. The case studies below illustrate typical outputs and provide insight into how the system performs.

The CDAO was used to extract descriptors from both the input and generated artifacts. Each artwork was analyzed by the Perceptor agent, producing a structured set of descriptors: themes, motifs, styles, and emotions. The generated translations were analyzed in the same way. The Curator agent then calculated the translation score.

5.1.1. Case Study A: Painting to Poem to Painting

Our first case study, presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, uses a painting as input (

Table 1—A), generates a poem, then translates that poem back into a painting (

Table 1—B). The source painting chosen is “The treasuries of Earth” by Keazim Isinov, a Bulgarian painter with a distinctive style [

68].

Observations:

The round-trip preserved the central theme of harvest and abundance across modalities. It is also interesting to observe the similarity of the composition of the generated painting to the original one.

5.1.2. Case Study B: Poem → Image → Poem (Round Trip)

The second case study, presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4, uses a poem as input, generates a painting (picture in

Table 3), then translates that painting back into a poem. The source poem chosen is “The Road Goes Ever On” by J.R.R. Tolkien [

69].

Overview: Round-trip translation preserved temporal motifs and contemplative affect across modalities, with minor lexical variation.

5.1.3. Case Study Summary

In the above case studies and others (total ~10 pairs tested), we observed the Curator agent typically needed at most one refinement iteration when issues arose. Two common types of interventions were noted:

- ●

Style drift—which we attribute to model pretraining bias.

- ●

Missing elements—which we attribute to the early phase of the prototype and the need for further development and refinement.

The case studies demonstrate that ontology-guided multi-agent translation preserves core motifs, affective tone, and stylistic orientation across modalities, while attenuating fine symbolic nuance and introducing minor lexical drift. Round-trip translations remained semantically coherent, confirming that the prototype maintained cross-domain alignment under ontology-based supervision.

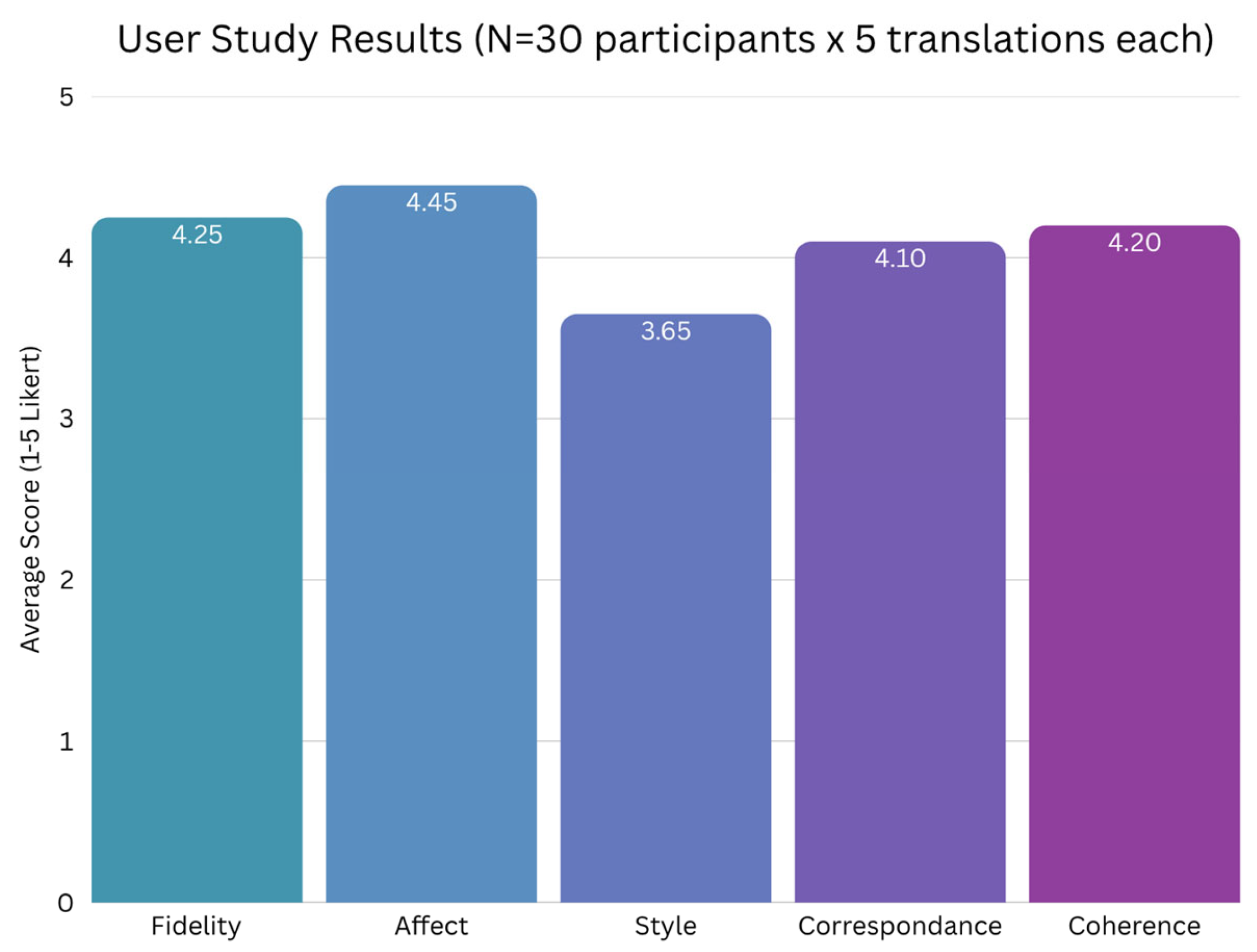

5.2. Quantitative User Study

To complement the system-level evaluation, we conducted a structured user study with non-specialist participants (N = 30). Each participant was able to create five randomly assigned original–translation pairs (e.g., painting → poem, poem → painting), ensuring a balanced distribution across modalities. In total, this procedure yielded 150 independent evaluations.

Although this phase is described as a quantitative user study for consistency with the overall evaluation design, it remains primarily qualitative in interpretation. The use of 5-point Likert-scale responses provides structured but inherently subjective impressions rather than statistically inferential data. Accordingly, the findings are interpreted as indicative trends reflecting perceived fidelity, affect, and style rather than as outcomes of formal hypothesis testing.

The evaluation involved thirty anonymous participants, all of whom were enrolled university students. No additional demographic information was collected. The participants represented a range of academic disciplines, primarily within the humanities and computer science. None were professional visual artists or poets. Given their academic context, participants were presumed to possess a general level of cultural literacy and interpretative capacity appropriate for lay evaluation. This composition was considered consistent with the intended non-specialist user group of the system and provided a representative basis for assessing cross-domain artistic translation outcomes.

Participants assessed the translations using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) across five predefined dimensions, designed to capture semantic, affective, and aesthetic fidelity:

Fidelity: The translation preserves the main theme of the source.

Affect congruence: The emotional tone matches the source.

Style transfer: The style/voice is appropriate for the target medium while reflecting the source.

Correspondence clarity: The mapping between source and target elements is clear and convincing.

Target coherence: The result is coherent and high-quality in its own medium.

The evaluation protocol was integrated directly into the prototype. After each translation was generated, participants were automatically prompted to complete the questionnaire, which ensured immediate reflection and complete coverage of responses.

The aggregated data, presented in

Figure 8, shows encouraging outcomes. Average scores were: Fidelity = 4.25, Affect = 4.45, Style = 3.65, Correspondence = 4.1, and Coherence = 4.2, producing an overall mean of 4.13, which falls within the “Good–Excellent” range. This indicates that, overall, the system achieved reliable cross-domain alignment and generated outputs that participants judged as coherent and faithful. The highest rating was obtained for affect congruence, suggesting that emotional tone is preserved effectively across modalities. The lowest score was observed for style transfer, highlighting that fine-grained stylistic adaptation remains the most challenging aspect and an important target for refinement.

5.3. Qualitative Expert Study

To complement the quantitative evaluation, we collected critical reflections from three practicing artists: a painter, a poet, and a sculptor, inviting them to review the prototype. Their accounts highlight both its promise and its current limitations across different artistic disciplines.

Painter’s perspective: The painter emphasized the prototype’s strength in conceptual correspondence: motifs, themes, and compositional structures were rendered with consistency and clarity, surpassing what free-form prompting typically achieves. At the same time, the subtleties of brushwork, light, and chromatic tension were described as generic, producing images that were visually adequate but emotionally flatter than hand-painted works. The system was ultimately regarded as a “collaborator”, capable of stimulating new ideas, but not a substitute for embodied artistic intuition.

Poet’s perspective: The poet observed that translations from the visual to textual domain succeeded in capturing atmosphere and metaphor, drawing resonances between shapes and words. However, the generated verses lacked the unpredictability and real intensity that give poetry its transformative power. The round-trip (poem → painting → poem) was described as especially revealing, demonstrating that translation always reshapes rather than simply transfers meaning. The poet concluded that the prototype functions as a “companion in poetic thinking”, providing scaffolds for creativity rather than finished poetic voices.

Sculptor’s perspective: The sculptor highlights a high degree of fidelity to the source motifs, with the generated texts accurately capturing the characteristic elements of the input images. A clear semantic and emotional resonance is observed, as the system effectively interprets the underlying idea of the image and conveys a convincing emotional impact. Stylistic correspondence between visual features and their textual rendering further reinforces the sense of consistency. The aesthetic value is considered significant but requires deeper evaluation by experts in literature and aesthetics, while recommendations for improvement include extending the system’s capacity for three-dimensional perception. Overall, the system is described as an impressive and provocative experimental tool with broad potential for application across diverse social and cultural contexts.

Taken together, these reflections suggest that the prototype is not perceived as a replacement for artistic practice but rather as an auxiliary agent, as a structure builder that captures semantic and stylistic correspondences across media. Its value lies in stimulating dialog between concept and form, while its limitations underscore the enduring importance of materiality, embodiment, and aesthetic risk-taking in human art-making.

5.4. Comparison to LLMs

We note that our evaluation did not emphasize systematic comparisons with large foundation models. Existing systems such as ChatGPT, Gemini, or Grok are not designed for cross-domain art translation and therefore do not constitute fair baselines. Instead, we prioritized case studies, lay user studies, and expert reviews to capture both functional performance and artistic value. In future work, we plan to incorporate lightweight baseline pipelines (e.g., direct poem prompts to text-to-image models, or image captioning plus poeticization) to further situate our approach within the broader generative landscape, while keeping the focus on ontology-guided translation across domains.

5.5. Summary

Across case studies, user studies, and expert reviews, the evaluation demonstrates that the prototype achieves credible cross-domain art translation, while highlighting areas for refinement. Case studies (~10 pairs) showed that most translations required at most one refinement, with style drift and missing elements as the main issues, yet round-trip outputs remained semantically coherent. A structured user study (N = 30; 150 evaluations) yielded encouraging mean ratings (overall = 4.1/5), with affective tone most reliably preserved and style transfer identified as the main challenge. Expert reflections from a painter, poet, and sculptor confirmed the system’s ability to capture motifs, themes, and atmosphere, while also noting limitations in nuance, materiality, and intensity. Collectively, these findings suggest that the system functions not as a substitute for artistic creation, but as an auxiliary agent that supports creative dialog and preserves core semantic and affective correspondences across modalities.

6. Applications and Use Cases

Since the problem of art translation spans different domains and has intrigued scientists from various fields, we will now discuss a few envisioned use cases for a system like ours, highlighting how multi-modal translation could enrich experiences in different areas:

Creative Co-Pilot for Artists—Generative AI is increasingly adopted as a creative partner, but black-box models often produce semantically plausible yet ungrounded outputs. Our system enables artists to explore alternative modalities of their own work. For instance, a painter generating poetry that reflects the emotional tone of a canvas or a composer visualizing melodies through abstract imagery. By grounding translations in the ontology, artists can trace and control how motifs and emotions are preserved, fostering explainable co-creation rather than opaque output.

Education and Cross-Disciplinary Learning—Pedagogical studies highlight that multimodal representations enhance conceptual understanding and engagement [

70,

71]. In literature classes, students could transform a poem into a painting to better grasp metaphor and imagery. In music education, hearing a poem translated into music may highlight rhythm and mood. Unlike direct generative pipelines, our ontology-guided approach ensures conceptual fidelity, making it particularly suited for teaching creative reasoning across modalities.

Entertainment and Media Production—Multimedia storytelling increasingly relies on AI to generate cross-modal content [

72]. Our framework can automatically generate complementary modalities, such as illustrations for audiobooks or music scores for visual sequences, while preserving narrative themes and style. This capability lowers production costs for independent creators and supports scalable cross-modal enrichment in interactive media, with the added advantage of transparent mappings between modalities.

Therapeutic and Wellbeing Applications—Art therapy emphasizes translating feelings into multiple expressive forms [

73]. Systems that convert a drawing into music or a narrative into imagery can help individuals externalize emotions in new ways. By explicitly encoding affective states in the ontology, our system guarantees that therapeutic intent (e.g., calmness, sadness, hope) is preserved during translation. This offers more reliable tools for therapists and wellbeing platforms seeking multimodal emotional expression.

Synesthetic and Immersive VR/AR Experiences—Human–computer interaction research increasingly explores multimodal interaction in immersive environments [

74]. Our MAS could power virtual galleries where paintings dynamically generate accompanying soundscapes or VR platforms where user-created music spawns visual patterns in real time. Ontology-based mappings ensure consistency between modalities, avoiding incoherent pairings and thereby delivering meaningful synesthetic experiences.

Cultural Heritage and Accessibility—Museums and cultural institutions are adopting AI to enhance visitor engagement and accessibility. In heritage contexts, our system can generate poetic and musical interpretations of traditional artifacts (e.g., Bulgarian folk costumes, dances [

75], or embroidery patterns), making intangible culture accessible across senses. For visually impaired users, paintings can be translated into evocative musical pieces or poems. Conversely, for hearing-impaired audiences, music can be visualized as symbolic imagery. Ontology-grounded correspondences ensure that these translations respect cultural semantics and aesthetic authenticity.

Across these domains, the system’s unique strength lies in coupling generative capacity with semantic alignment and explainability. By anchoring translations in an explicit ontology, the MAS guarantees that cross-domain outputs are not only aesthetically plausible but also faithful to the meaning, affect, and style of the original work, thereby enabling trustworthy applications in creativity, education, therapy, entertainment, and cultural heritage.

7. Discussion

The evaluation results demonstrate that the proposed system achieves a balance between fidelity to the source artwork and creative enrichment in the target modality. Lay user feedback highlights the system’s ability to generate translations that are both accessible and aesthetically engaging, with particularly strong appreciation for creativity. Expert assessments further validate the preservation of core themes and emotional resonance, while also identifying areas where stylistic subtlety and structural complexity could be refined. This dual-layer evaluation suggests that the system not only resonates with general audiences but also withstands professional scrutiny, albeit with noted limitations. Importantly, the findings align with broader goals in computational creativity research: producing outputs that are interpretable, emotionally meaningful, and capable of sustaining critical dialog across artistic domains. Future work will focus on addressing identified weaknesses, particularly improving clarity, rhythm, and stylistic depth, while also expanding evaluation protocols to include larger and more diverse participant groups.

Opportunities—The ability to transform content across modalities could reshape how we interact with the internet. Instead of passively consuming media, users may actively shape and translate it across domains, with intelligent systems acting as intermediaries. This would make content more fluid and multidimensional. For example, a blog post could automatically generate visual or musical counterparts when shared. Such possibilities enrich creativity but also blur traditional boundaries between art, music, and literature, raising questions of authorship, ownership, and authenticity.

General limitations—Despite promising results, limitations are clear. The fidelity of outputs is constrained by current generative models. Some poem results lack the depth of human writing and painting style drifts. As models advance to handle longer compositions or finer stylistic detail, quality will improve. Ontology coverage is another challenge. While it encodes themes, motifs, and emotions, subtleties like irony or symbolism remain difficult to capture. Expanding the ontology and allowing continual refinement through user feedback are priorities. Evaluation is also underdeveloped. Standardized benchmarks with multiple human “reference translations” are needed to compare AI outputs fairly across modalities.

Computational costs—In the prototype, the pipeline of the MAS invokes multiple LLMs and a diffusion model sequentially, yielding ~30 s latency per request on two GPU servers. We plan to reduce cost by distilling reasoning prompts, replacing general LLMs with domain-specific SLMs and employing LoRA-tuned diffusion models for specific styles. Because the MAS is modular, these substitutions do not alter interfaces or the ontology contract.

Ontology coverage and granularity—CDAO currently emphasizes high-level descriptors (Theme, Motif, Emotion, Style). This supports explainability but limits coverage of low-level features (meter, rhyme, brushwork, palette dynamics). We address this by extending vocabularies via SKOS-mapped imports (e.g., AAT, EmotionML), adding many-to-many mapping patterns for metaphor and composite motifs and combining OWL--RL with SHACL constraints for closed-world validation where required.

Human-AI Collaboration—The system is designed to augment, not replace, human creativity. It supports iterative loops where artists create, AI translates, and humans curate or guide results. Ontology controls ensure alignment with intent and maintain a sense of user control. Such collaboration could open new creative directions that neither humans nor AI would achieve alone. At the same time, these systems can serve as computational models for cognitive science, helping explore how humans map experiences across senses and symbols.

Representational Logics and Multimodal Translation—The usefulness of the approach proposed in the current work depends in part on the different ways the arts represent meaning. As noted by Pareschi in Centaur Art: The Future of Art in the Age of Generative AI [

76] and following Goodman’s distinction between analog and digital symbol systems [

77], artistic domains vary greatly in how they encode information. Painting and sound rely on continuous, sensory forms of expression, while literature and musical notation use discrete, symbolic codes. These differences create both challenges and opportunities for translating between media. Analog forms make direct symbolic mapping difficult because their meaning is often fluid and gradual, whereas digital forms allow precise translation but can lose some of their expressive depth. In the presented system, the ontology works as a shared language that connects these different forms by translating their key features into a common conceptual space. Through clear semantic grounding and cooperation between agents, the system helps balance symbolic precision with perceptual richness. In this way, the diversity of artistic representation becomes an advantage, supporting flexible reasoning and creative exchange across different artistic media.

Chaos Theory—In the broader theoretical frame, the system’s dynamics can be interpreted through the lens of chaos theory. Even small perturbations in the initial conditions of generation, such as a subtle change in an extracted motif or a Curator’s refinement, can cascade into disproportionately different outcomes in the translated artwork. This sensitivity to initial conditions echoes the “butterfly effect”, underscoring why an ontology-guided supervisory layer is essential. By constraining the search space with semantic anchors, the system mitigates the tendency toward divergent or unstable translations that pure generative models often exhibit. At the same time, a certain degree of controlled unpredictability is beneficial; it allows the emergence of novel and aesthetically surprising correspondences across domains, which is a hallmark of creativity. Thus, chaos theory provides a conceptual justification for balancing determinism (through ontological structure) and openness to variation (through generative stochasticity) in cross-domain artistic translation. Furthermore, a similar approach like ours can be used for image generation by complex mathematical equations or vice versa, such as listed by Kyurkchiev et al. [

78].

Comparative Perspective with Manual Art Translation—While the current study uses modern to its time approach, it is important to note that cross-domain art translation has long been practiced manually by human artists, poets, and composers. Classical examples include Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn [

79] and Auden’s Musée des Beaux Arts [

80], both poetic interpretations of visual artworks, as well as Rilke’s Archaic Torso of Apollo [

81], which translates the emotional and aesthetic impact of sculpture into verse. Conversely, Blake’s Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy [

82] and Chagall’s Song of Songs series [

83] exemplify the transformation of poetry into visual art. Musical analogs such as Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition [

84] and Kandinsky’s theory of sound–color correspondence [

85] extend this tradition into the auditory domain. A future comparative study could therefore juxtapose system-generated translations with such manually produced cross-domain works, assessing convergence in semantic fidelity, affective tone, and stylistic coherence. This would illuminate how closely algorithmic translation approximates human interpretive strategies across artistic media.

Future Directions—Our work highlights the potential of multi-agent architectures in creative domains. By combining reasoning, explanation, and generation, the system addresses key issues of alignment and interpretability in AI. Further progress will require advances in generative models, richer ontologies, and standardized evaluation methods. In parallel, interdisciplinary work with artists, ethicists, and cognitive scientists will be essential to address questions of authorship, transparency, and human–AI co-creation.

Future development of the prototype system will also focus on addressing current limitations and expanding its multimodal scope. At present, the implementation has been primarily evaluated within the painting–poetry translation domain, which, while effective in demonstrating cross-domain semantic transfer, represents only a subset of potential artistic correspondences. Subsequent iterations will extend the framework to encompass additional modalities such as music, dance, and architecture, requiring the integration of temporal and performative ontologies alongside multimodal embeddings capable of representing rhythm, movement, and spatial composition.

Enhancing the stylistic richness and aesthetic coherence of generated outputs also remains a central challenge. Planned improvements include fine-tuning generative components on curated cultural datasets and enriching the underlying aesthetic ontology to encode style, mood, and symbolism with greater granularity. Through these extensions, the system aims to evolve from a domain-specific translation framework into a general aesthetic reasoning platform, capable of interpreting and generating art across diverse sensory, temporal, and cultural modalities. Collectively, these developments are intended to position the system as a scalable and generalizable foundation for multi-domain computational creativity and exploration.

A further line of development concerns the human-in-the-loop (HITL) dimension of the architecture, which extends hybridization beyond artificial agents to include the human creator as an active participant. While the current prototype does not incorporate user feedback during processing, future iterations could embed human input as a structural element of the reasoning, translation, and generation loops. This perspective resonates with Pareschi’s concept of centauric integration, wherein human intentionality and machine generativity operate as complementary cognitive subsystems within a shared creative process, as elaborated in Centaur Art and Beyond Human and Machine: An Architecture and Methodology Guideline for Centaurian Design [

86]. The same systemic complementarity between centauric and multi-agent architectures is articulated by Borghoff et al. [

87] and Saghafian et al. [

88], suggesting that an ontology-driven MAS could evolve toward a fully HITL model in which human evaluative and affective judgments guide agent negotiation and refinement. Such an approach would transform the framework from an autonomous translator into an adaptive co-creative ecosystem integrating symbolic reasoning, generative synthesis, and human aesthetic agency.

8. Conclusions

This paper introduces a novel concept for an ontology-driven multi-agent system focused on translating artistic content across domains such as visual arts, music, and poetry. By combining symbolic knowledge representation with generative AI models, the system addresses two major gaps in existing multimodal generation: the lack of semantic alignment and the absence of interpretability. The Cross-Domain Art Ontology (CDAO) provides a shared semantic interlingua, while the modular agent architecture ensures traceability and controllability across perception, translation, generation, and curation tasks.

The prototype demonstrates that meaningful cross-domain translations are feasible. Artworks in one modality can be transformed into another while retaining motifs, themes, and affective tone. Beyond aesthetic novelty, the system contributes to the growing paradigm of neuro-symbolic creative AI, where knowledge-based reasoning augments generative capacity to yield outputs that are explainable, culturally informed, and aligned with human intent.