1. Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage: Context and Challenges

Cultural heritage conservation operates at the intersection of traditional preservation methodologies and emerging technological capabilities. Archaeological sites, historic buildings, museum collections, and architectural monuments face accelerating environmental threats, structural degradation, and resource constraints that demand innovative approaches transcending reactive maintenance paradigms [

1,

2].

Artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved over the past decade from experimental prototypes to operational systems in cultural heritage applications. The integration of neural networks [

3,

4], fuzzy logic [

5], and Internet of Things (IoT) sensor networks [

6,

7] offers unprecedented capabilities for continuous monitoring, automated diagnosis, and predictive maintenance. However, despite significant technological progress, three fundamental challenges limit practical adoption and scalability of AI systems in heritage conservation:

Heritage buildings generate multi-parameter sensor streams (thermal, vibration, pressure) with complex non-linear relationships. Traditional threshold-based monitoring fails to capture subtle deterioration patterns that manifest through parameter interactions rather than individual exceedances [

8].

Conservation professionals demand transparent, explainable maintenance recommendations that align with established practice protocols. The algorithmic opacity of high-performance neural networks creates barriers to professional validation and institutional acceptance [

9,

10].

False alarms waste limited conservation resources, while missed faults risk irreversible damage to cultural assets. The accuracy–interpretability trade-off inherent in current AI approaches forces practitioners to choose between predictive performance and decision transparency [

11].

Recent research demonstrates substantial progress in applying AI techniques to heritage monitoring and maintenance. Pacifico et al. [

12] combined support vector machines and decision trees for multi-class fault classification in Italian archaeological sites and Spanish ecclesiastical structures, achieving over 95% predictive accuracy in environmental anomaly detection. This work established benchmarks for automated heritage monitoring systems while highlighting challenges in interpretability for conservation practice.

Deep learning approaches have shown particular promise for structural damage detection. Casillo et al. [

13] applied convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to detect condensation and biological deterioration, surpassing 95% accuracy through integration of autoencoders for anomaly detection and generative adversarial networks (GANs) for synthetic data augmentation. However, these high-performance architectures exhibit limited interpretability, constraining adoption in conservation contexts where decision transparency is essential [

14].

Digital twin concepts and heritage building information modeling (HBIM) have complemented machine learning advances by linking sensor data to 3D models for predictive simulation of degradation processes [

15]. While these comprehensive systems enable sophisticated monitoring and modeling, they require substantial computational resources that may exceed the capabilities of many heritage institutions, potentially creating a digital divide in conservation access [

16].

Addressing practical deployment concerns, Perles et al. [

17] designed energy-efficient IoT architectures using adaptive sampling and edge computing, extending sensor lifetimes while maintaining continuous monitoring. This work demonstrates that long-term automated monitoring is technically and economically feasible for heritage sites. Furthermore, AI is enhancing non-destructive testing (NDT) capabilities through hyperspectral imaging, ground-penetrating radar, and acoustic emission monitoring [

18], though these techniques produce large datasets requiring advanced algorithms and computational resources for effective interpretation.

Despite these advances, several fundamental limitations constrain AI system effectiveness in heritage conservation:

Neural networks and deep learning models achieve high precision but remain algorithmically non-transparent [

19], whereas fuzzy logic systems provide explainable reasoning but demonstrate reduced accuracy in complex classification tasks [

20,

21]. This trade-off forces practitioners to sacrifice either predictive performance or decision transparency.

Most studies present qualitative results without standardized metrics [

12,

13], restricting objective benchmarking and system integration capabilities [

22]. The absence of common assessment frameworks makes it difficult to determine which approaches perform optimally across different heritage contexts.

Current implementations typically remain confined to pilot projects or single-site deployments. Sustainability assessments rarely quantify energy consumption, resource demands, or lifecycle impacts comprehensively [

15]. Computational requirements of digital twins and HBIM systems further limit accessibility for smaller institutions.

While long-term IoT monitoring has proven technically feasible [

17], heterogeneous sensor networks lack standardized integration protocols. Advanced NDT techniques [

18] generate large datasets requiring technical capacities often beyond heritage organizations’ capabilities.

The current state of research reveals several critical opportunities: developing standardized evaluation frameworks for objective system comparison [

23], establishing interoperability protocols for integration with existing heritage management platforms, conducting cross-cultural validation beyond the current European geographic concentration [

12,

13], and embedding sustainability considerations through lifecycle assessment methodologies tailored to heritage applications [

15].

This paper addresses these identified gaps through development and validation of a hybrid neuro-fuzzy system optimized for proactive maintenance in cultural heritage environments. The research advances AI applications in heritage conservation through sequential integration of feedforward neural networks (FF-NNs) for pattern recognition with Mamdani-type fuzzy inference systems (MFISs) for interpretable decision-making, overcoming the accuracy–interpretability trade-off. In addition, the proposed approach establishes a comprehensive evaluation methodology including fault detection accuracy metrics, computational efficiency indicators, interpretability assessments, and statistical validation across multiple runs. Furthermore, the systematic evaluation across diverse heritage preservation scenarios demonstrates the system’s capabilities and limitations in real-world operational contexts.

The FF-NN architecture provides the ability to handle sensor data complexity and achieve high predictive accuracy but exhibits algorithmic non-transparency, limiting conservation professional validation. Conversely, the MFIS addresses interpretability requirements through transparent, explainable recommendations but demonstrates reduced predictive accuracy compared to the FF-NN in complex pattern recognition tasks. The proposed hybrid approach leverages complementary strengths while acknowledging inherent limitations revealed through rigorous empirical testing.

In this framework, this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the comprehensive methodology including system architecture design, mathematical formulation, and evaluation frameworks.

Section 3 details hybrid system design and implementation.

Section 4 presents simulation results and performance analysis.

Section 5 provides integrated system evaluation, followed by conclusions and future research directions.

2. Methodology

This paper develops a hybrid intelligent system for proactive maintenance of cultural heritage sites, specifically addressing critical gaps in interpretability, predictive accuracy, and sustainability that limit current AI applications in conservation practice. The methodology integrates neural network pattern recognition capabilities with fuzzy logic decision-making processes to enable early fault prediction and optimization of maintenance schedules while maintaining the transparency required by conservation professionals.

2.1. System Architecture Overview

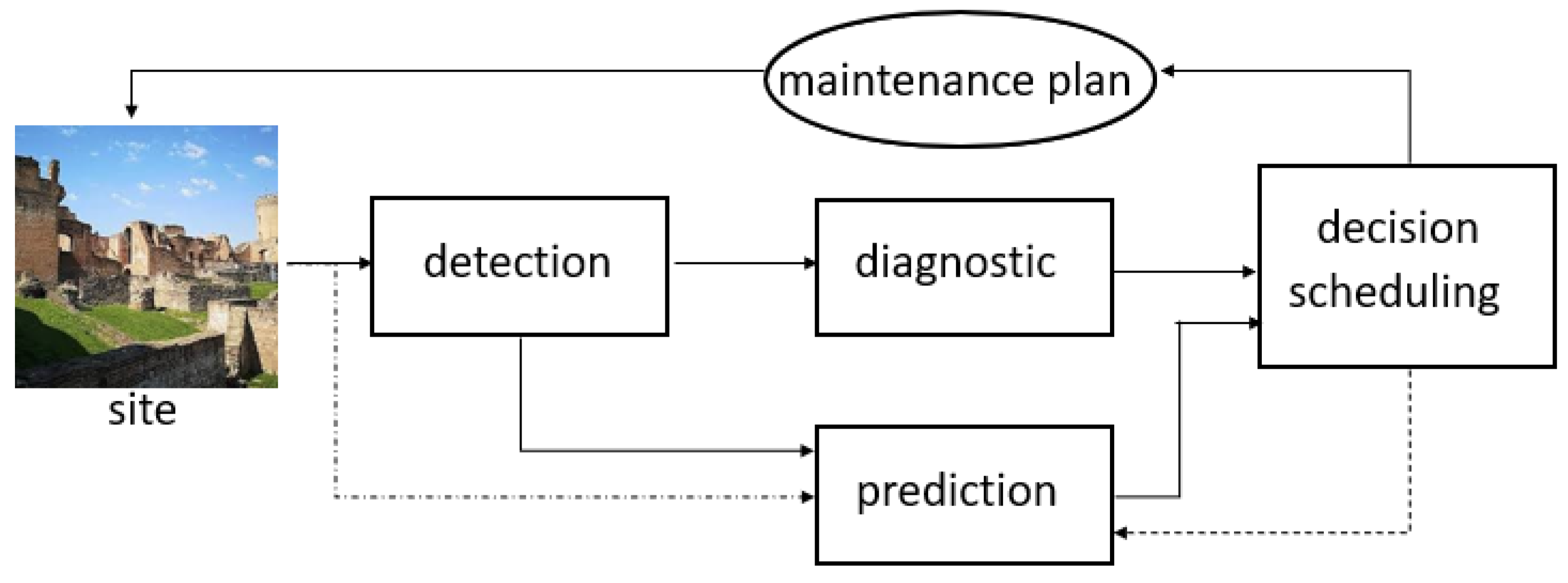

The proposed framework integrates a sequential processing architecture that exploits the complementary strengths of neural networks and fuzzy inference systems (

Figure 1). This hybrid design addresses the fundamental trade-off between predictive accuracy and interpretability that has historically limited AI adoption in heritage conservation.

The system architecture incorporates two modules: a feedforward neural network (FF_NN) module that provides for initial fault prediction, and provides high classification accuracy through its ability to model complex, non-linear relationships in sensor data; and a Mamdani-type fuzzy inference system (MFIS) that generates interpretable maintenance recommendations aligned with established conservation protocols.

This sequential design ensures that while neural networks deliver the computational power necessary for accurate predictions, fuzzy logic maintains the interpretability essential for decision-making in heritage conservation contexts.

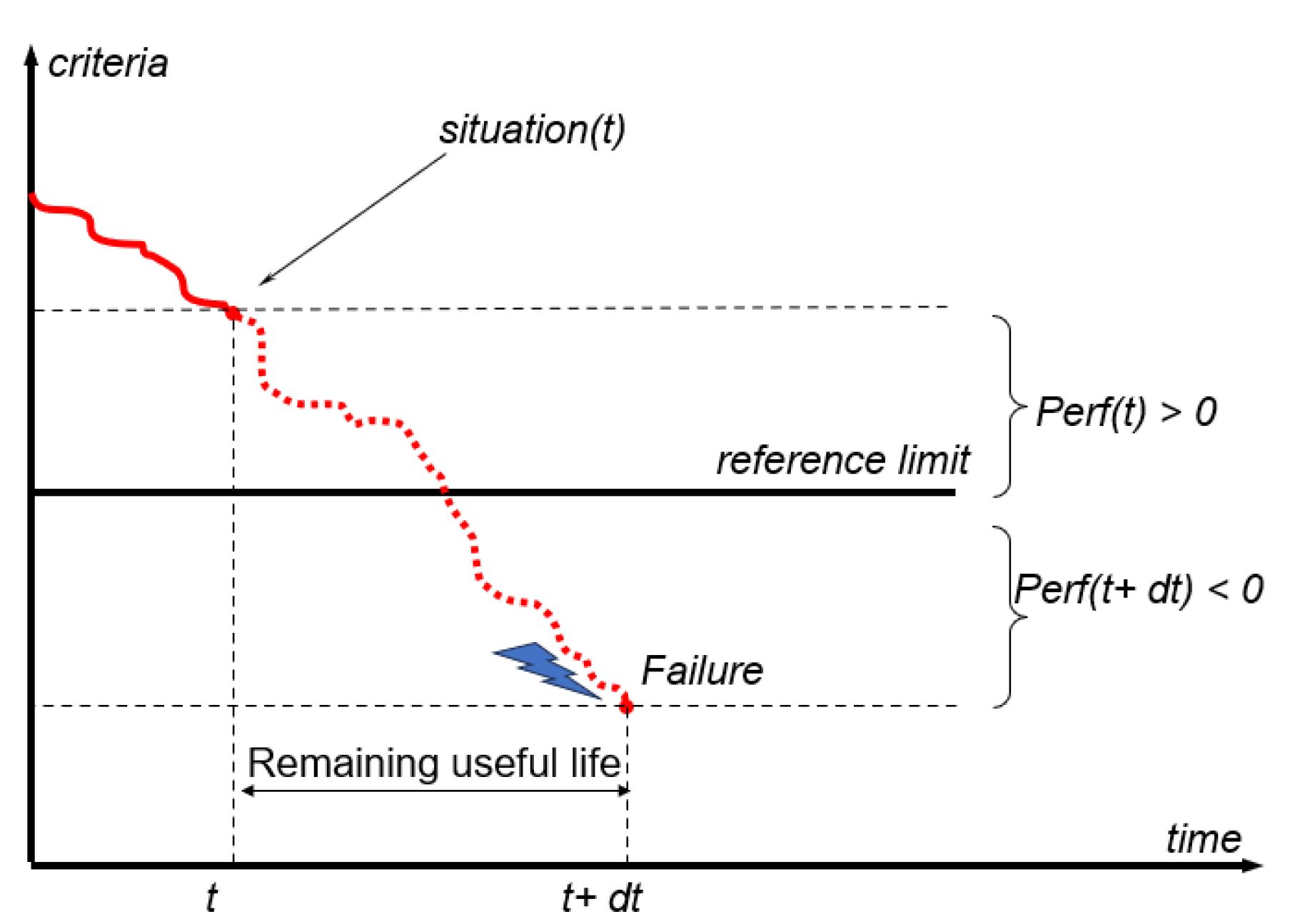

The fault prediction methodology follows a systematic assessment process that enables early detection of deterioration patterns before they result in irreversible damage (

Figure 2). This proactive approach allows conservation professionals to implement proactive measures while preserving the integrity of archaeological assets and optimizing resource allocation.

The assessment process incorporates temporal analysis of sensor data patterns, enabling the system to distinguish between normal environmental variations and real deterioration indicators. This capability is essential for reducing false alarms while maintaining sensitivity to authentic fault conditions that require intervention.

The integrated system operation can be mathematically expressed through Equation (1):

where

NN(x) represents neural network fault classification output;

x denotes the sensor input vector dependent on temperature measurements (temp), pressure values (p), and vibration (v);

t represents temporal context for trend analysis.

This formulation captures the sequential nature of the hybrid system, where neural network outputs serve as inputs to the fuzzy inference system for final decision-making.

2.2. Data Processing and Integration

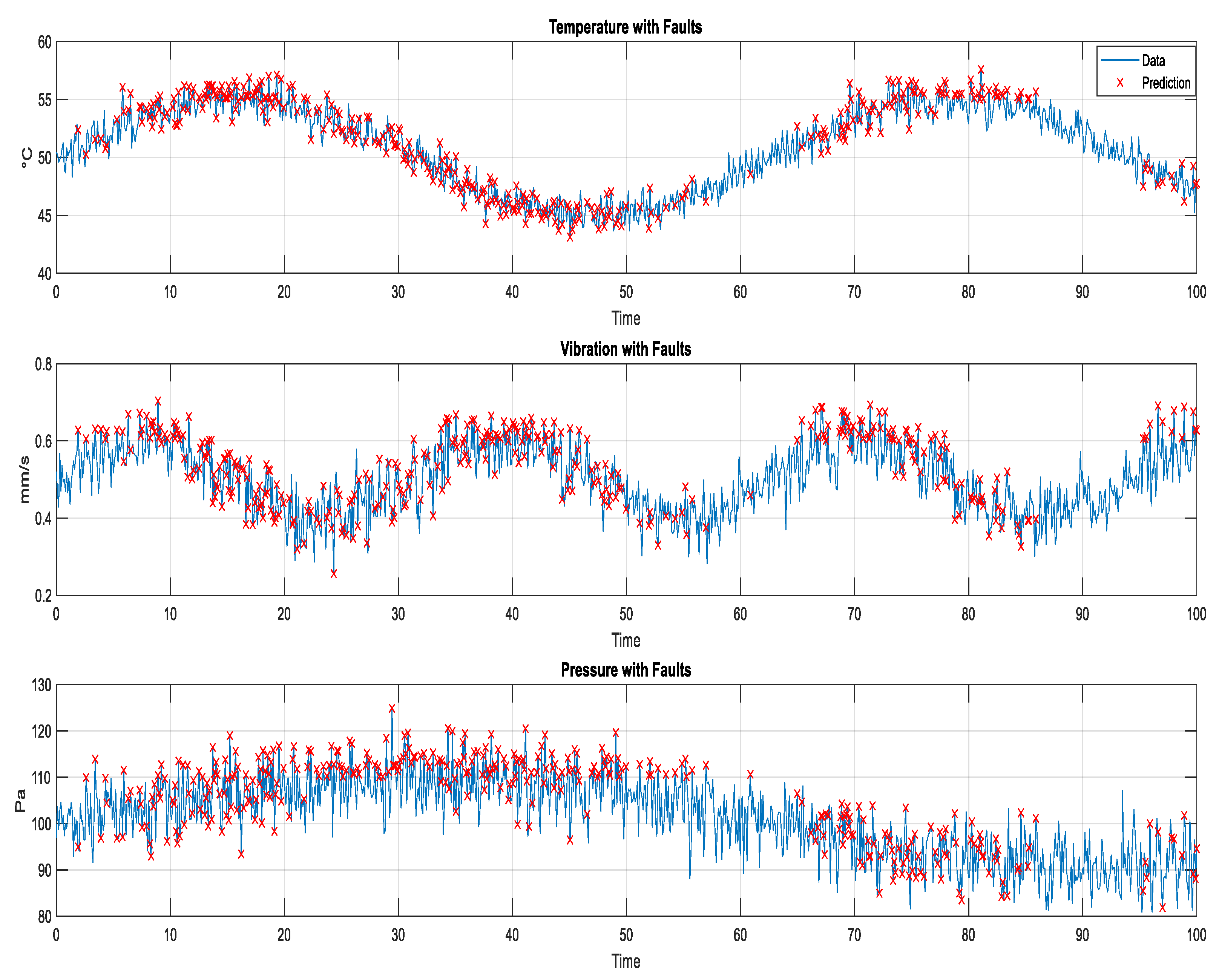

The system processes heterogeneous sensor data including temperature measurements, vibration amplitudes, and pressure variations. Synthetic monitoring data was generated to represent a full annual cycle (365.25 days) of heritage building operation, producing 1000 samples across three sensor modalities.

Temperature Data: Ranges [12–28 °C] with baseline seasonal cycles parameterized in Equation (2) as

where

Pressure Data: Measurements (normalized to 0–100 scale) generated with baseline values of 50 units, seasonal variation of ±15 units, reflecting atmospheric pressure cycles. HVAC system response modeled through first-order lag functions with time constants of 2–4 h capturing realistic thermal inertia in massive stone structures.

Vibration Data: Ranges [0–50 m/s

2] incorporating structural background noise (1–3 m/s

2 under ambient conditions per ISO 10816 [

25]) with harmonic components reflecting mechanical equipment operation (HVAC compressors, ventilation fans operating at 15–60 Hz).

Fault Condition Generation: Synthetic fault conditions were injected into samples distributed across three fault classes: thermal stress: temperature variations ± 5 °C beyond seasonal ranges sustained for >2 h; pressure anomalies: sudden ±20-unit deviations indicating HVAC failure or structural seal breach and mechanical degradation; vibration amplitudes > 20 m/s2 sustained across 5–50 Hz indicating bearing wear or structural looseness.

These parameter ranges were selected based on published conservation standards (ISO 11799 [

26] for archival environments, ASHRAE 2020 [

24] guidelines for heritage building climate control) and typical sensor specifications for structural health monitoring in European monuments.

Data Preprocessing: Sensor inputs were normalized using min–max scaling. The preprocessing pipeline includes normalization procedures ensuring compatibility across diverse monitoring environments, statistical outlier detection algorithms, and feature extraction techniques optimized for heritage monitoring applications.

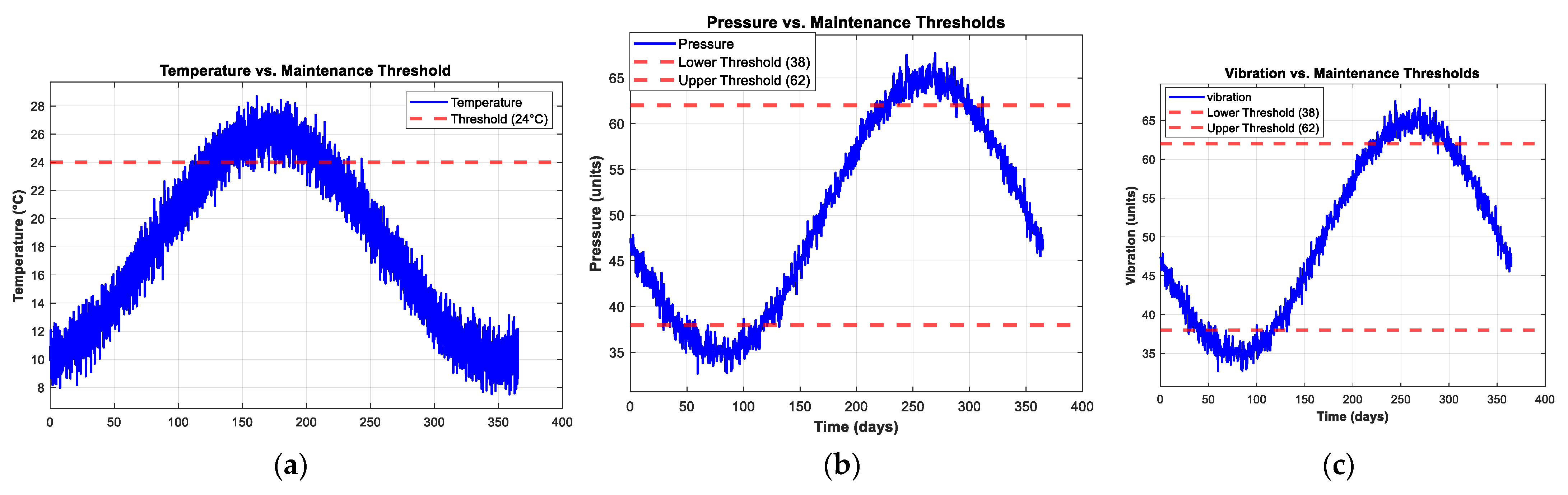

Data Partitioning Strategy: Samples were systematically partitioned using stratified sampling: FF-NN training/testing: 70% (701 samples, 172 faults)/30% (299 samples, 73 faults); fault rate: 24.50% representing realistic class imbalance in maintenance applications; and hybrid system evaluation: 150 samples with 93 faults (62.40% fault rate) to establish meaningful rule boundaries in MFISs.

The hybrid system processes heterogeneous sensor data like temperature measurements, vibration amplitudes, and pressure variations. The used training and testing dataset includes temperature (

Figure 3a), pressure (

Figure 3b), and vibration (

Figure 3c) measurements.

3. Hybrid System Design and Implementation

3.1. Feedforward Neural Network Module

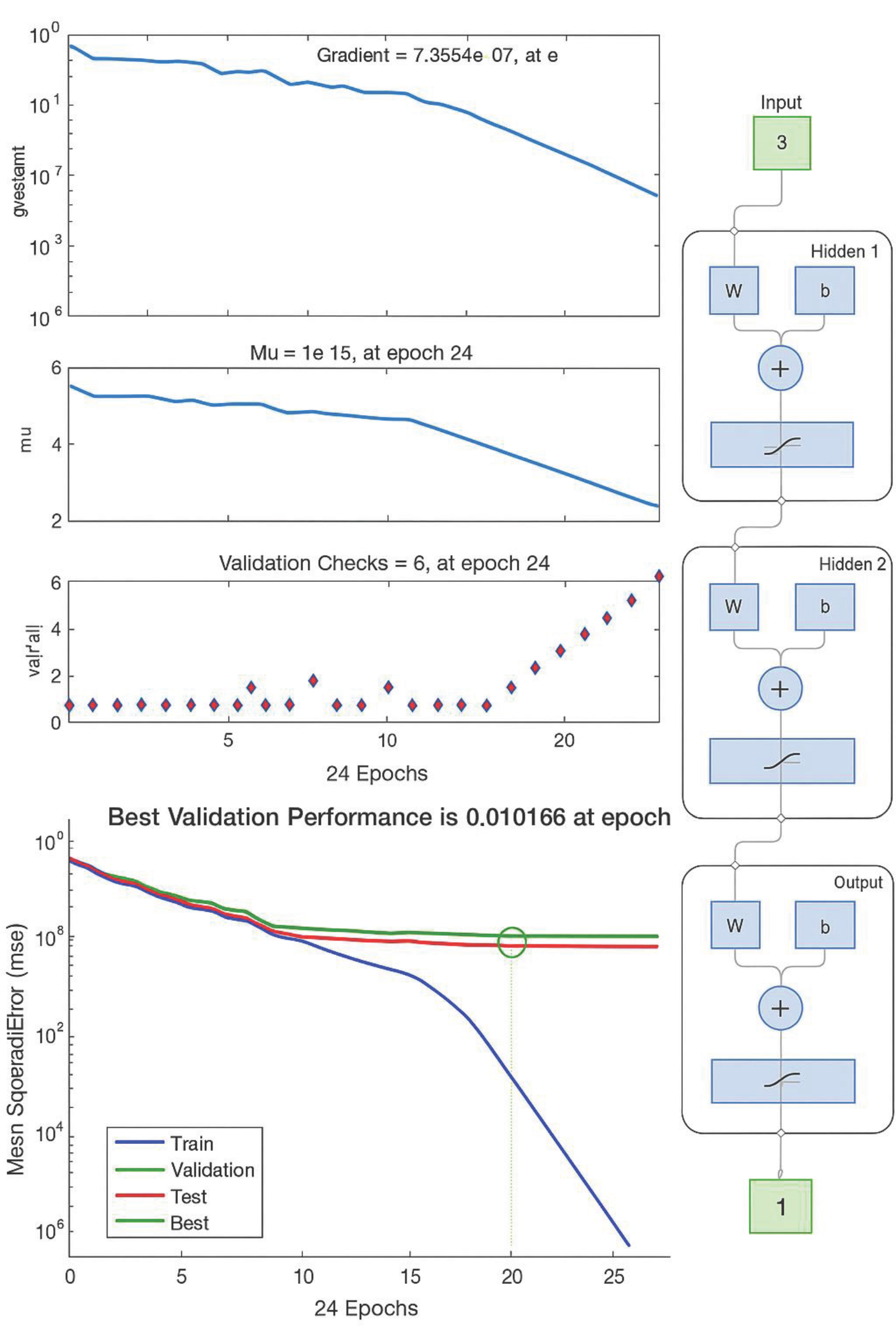

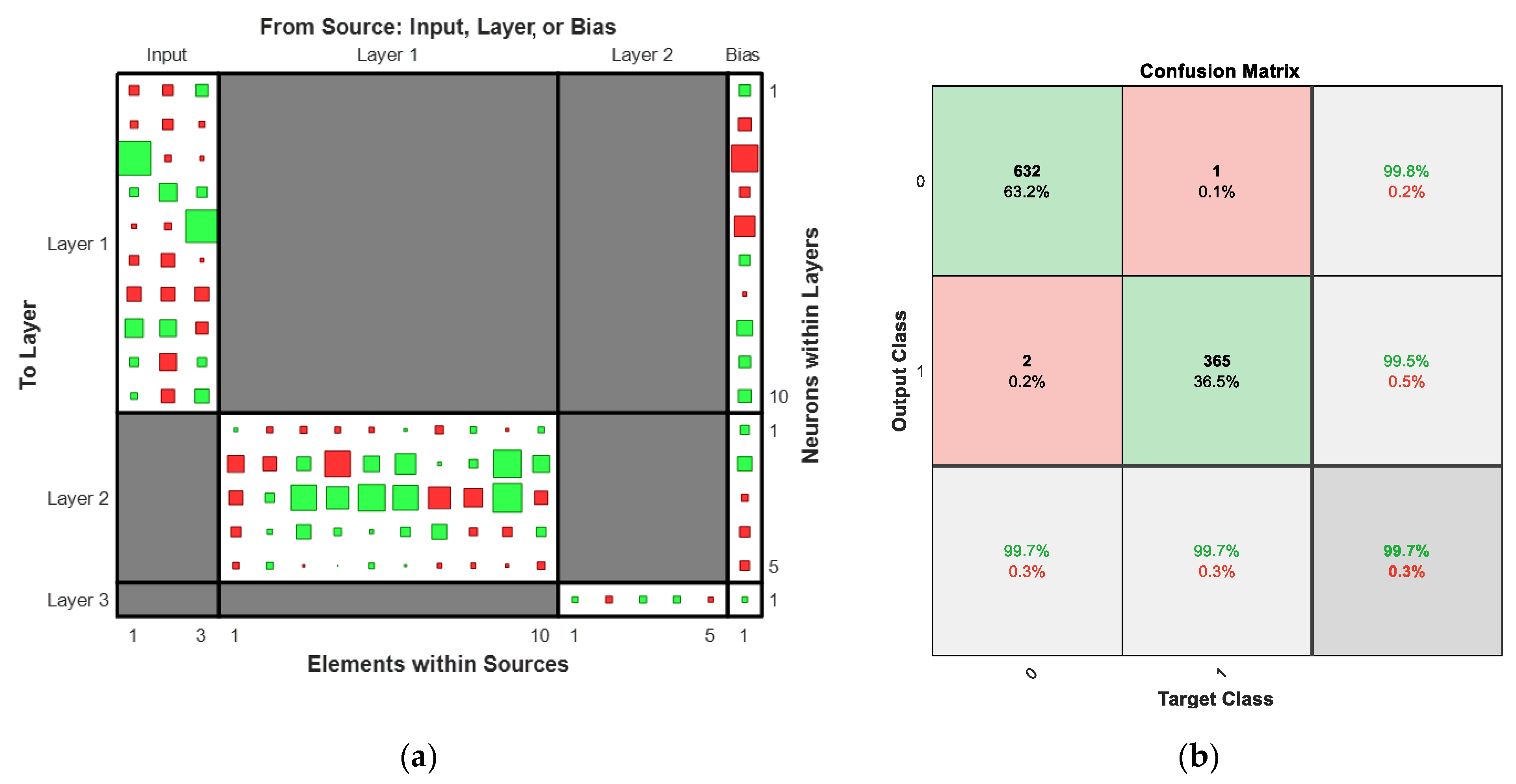

The FF-NN module implements a feedforward multilayer perceptron architecture specifically optimized for fault detection in heritage assets. The NN structure (

Figure 4) includes an input layer with 3 neurons (temperature, vibration, pressure) normalized with dimensionality defined by sensor measurement vectors, two hidden layers containing 10 (hidden layer 1) and 5 neurons (hidden layer 2), respectively, and a single output neuron providing binary fault classification probabilities. Sigmoid activation functions are implemented across hidden layers to introduce non-linearity with gradient stability during backpropagation training. The output neuron applies sigmoid transformation, producing probability values within the [0, 1] range to support threshold-based decision-making processes required for maintenance recommendations.

The training configuration uses the Levenberg–Marquardt backpropagation algorithm, L2 regularization, 500 maximum epochs, the convergence threshold 10−6, and random seed: 42 (reproducibility).

The FF-NN training step uses the scaled conjugate gradient backpropagation algorithm with adaptive learning rate adjustment mechanisms to ensure efficient convergence [

27]. Data partitioning follows a systematic 70% (701 samples with 172 faults) −30% (299 samples and 73 faults) split for training and testing phases of the FF-NN, with stratified sampling guaranteeing balanced representation of diverse fault scenarios across all datasets. The hybrid test evaluation system uses 150 samples with 93 faults [

28].

Overfitting prevention integrates multiple regularization strategies including early stopping based on validation performance monitoring and L2 weight bias regularization (λ = 0.001). Learning robustness is verified through k-fold cross-validation (k = 10), confirming generalization stability across different data partitions and ensuring reliable performance in varied operational conditions.

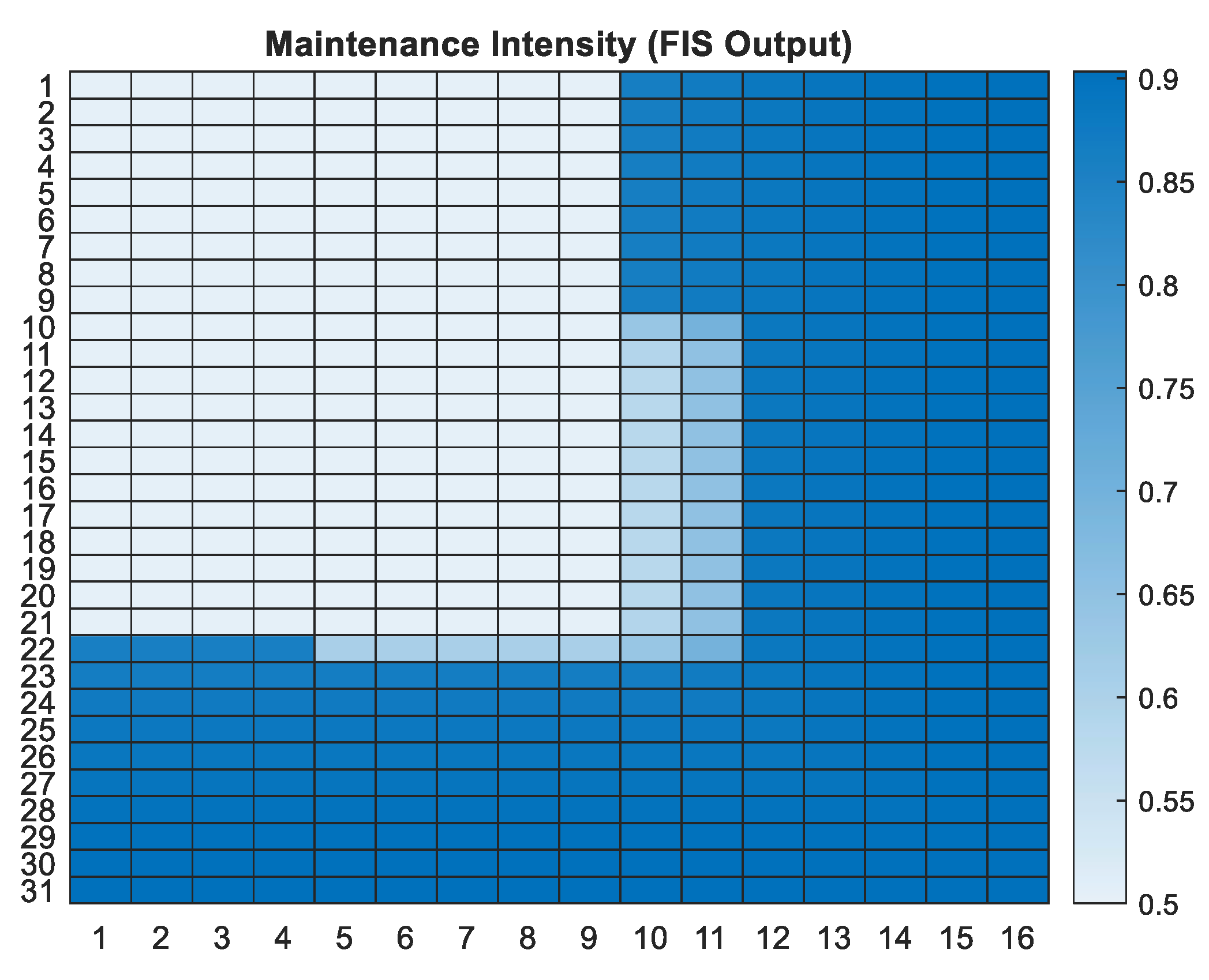

Training evaluation relies on comprehensive metrics including mean squared error (MSE) for regression optimization, alongside accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for classification performance assessment. The stop criteria combine maximum epoch limits (500 iterations), convergence thresholds (10−6 error reduction), and validation plateau detection, ensuring both training reliability and computational efficiency. The fuzzy inference system (FIS) provides interpretable maintenance recommendations by processing sensor inputs through expert knowledge-driven rule structures. This module of the hybrid system proposed addresses the interpretability requirements essential for heritage conservation practice, where decision transparency enables professional validation and builds confidence in automated recommendations.

3.2. Mamdani-Type Fuzzy Inference System Module

The fuzzy inference system provides interpretable maintenance recommendations by processing sensor inputs through expert knowledge-driven rule structures. This module addresses interpretability requirements essential for heritage conservation practice, where decision transparency enables professional validation.

Input and output membership function design, their significance, and associated predicted fault conditions are summarized in

Table 1, providing a comprehensive framework for linguistic variable interpretation.

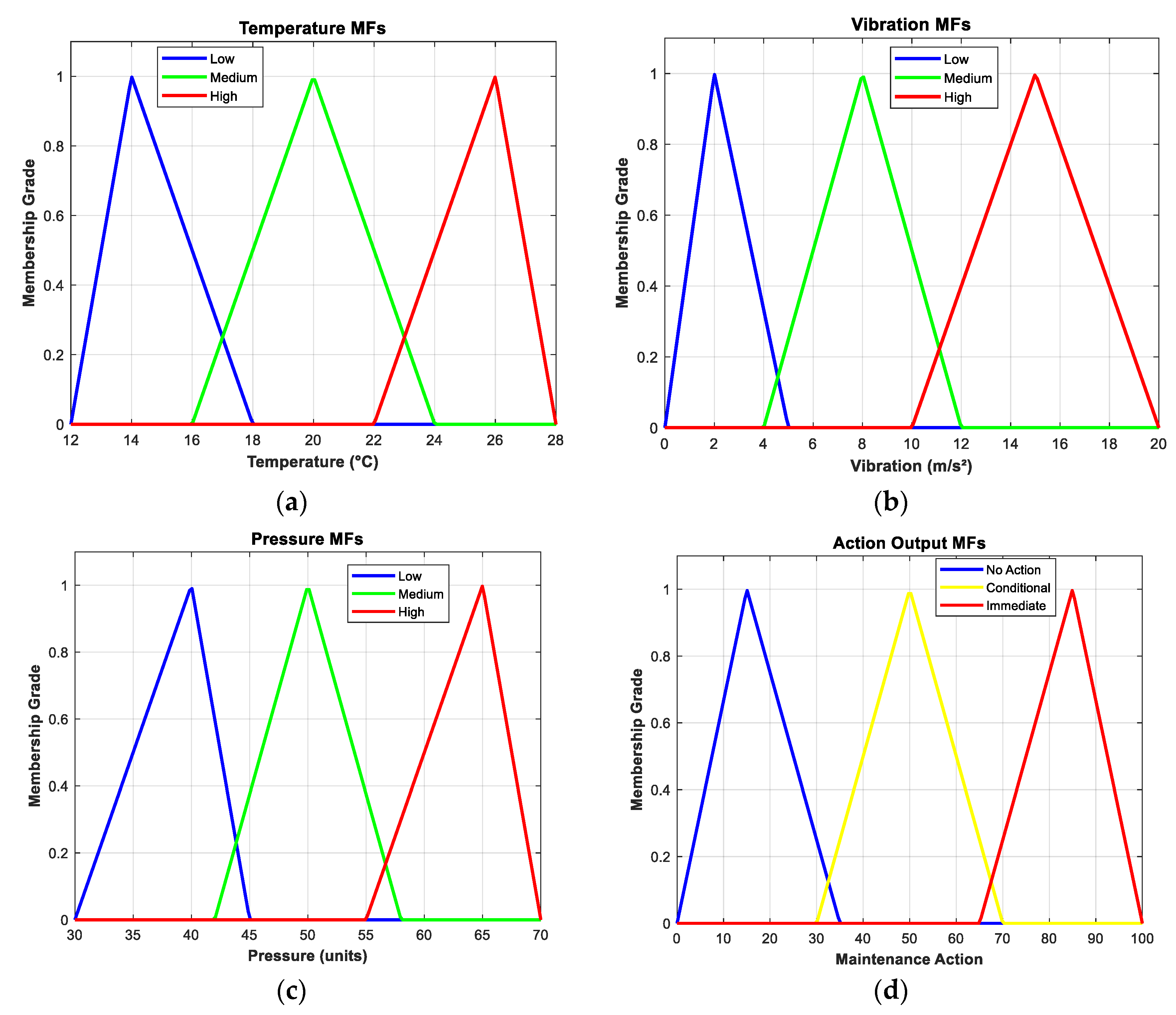

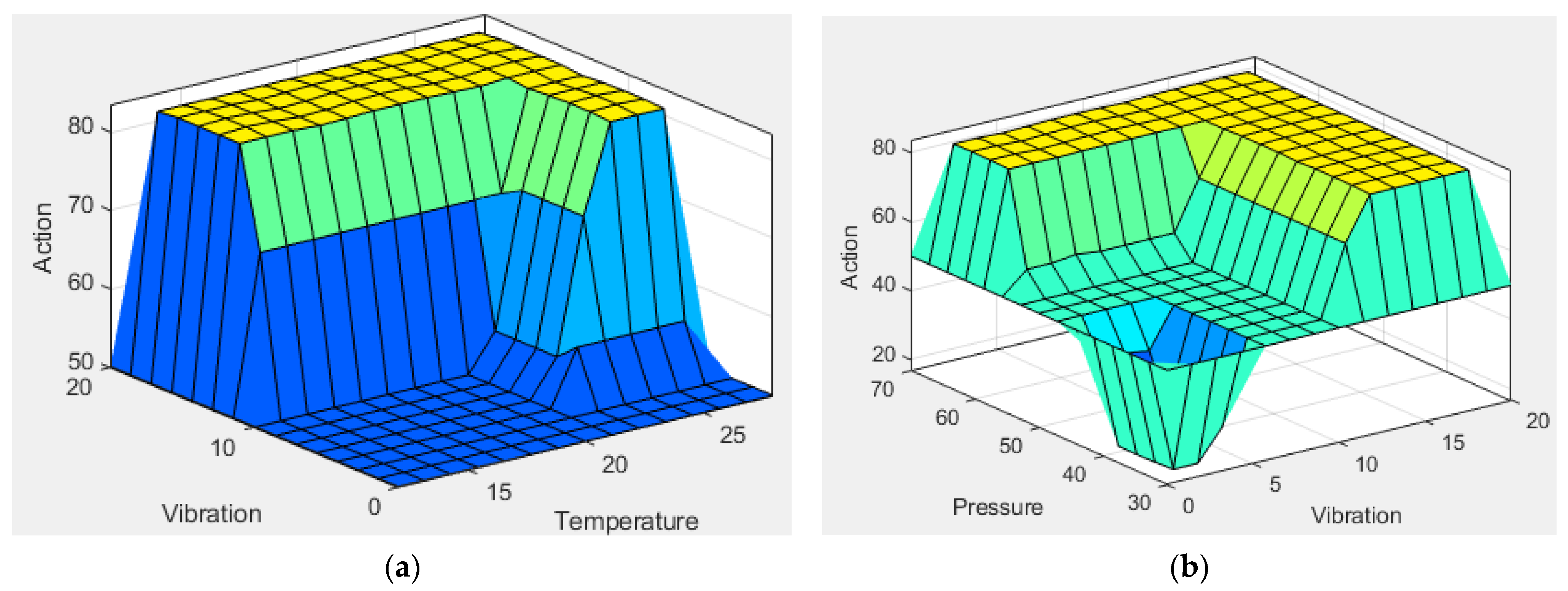

The fuzzy membership functions associated with the inputs and outputs (

Figure 5) integrate expert knowledge systematically selected from heritage conservation practitioners through structured knowledge acquisition processes.

The 30% overlap between normal and medium (18–21 °C range) MFs associated with temperature (

Figure 5a) allows fuzzy rules to treat borderline temperature conditions with a graduated response rather than sharp transitions. A 20 °C reading produces partial membership in both normal (μ = 0.67) and medium (μ = 0.33) MFs, triggering intermediate maintenance rules rather than binary decisions.

Vibration (

Figure 5b) fault progression is faster than thermal, so a tighter 25% overlap reduces conditional maintenance cases and emphasizes binary urgent/normal distinction. A 5.5 m/s

2 reading produces μ = 0.75 for low (still normal) and μ = 0.25 for medium, allowing rules to defer maintenance on borderline cases where noise may dominate the signal.

Pressure systems exhibit coupled dynamics where simultaneous changes across multiple parameter ranges are common (e.g., temperature rises; consequently, pressure rises). The 35% overlap of MFs associated with pressure (

Figure 5c) creates strong rule interactions between pressure and temperature conditions, allowing the FIS to recognize correlated faults spanning multiple physical mechanisms.

Hybrid system MFs associated with the outputs (

Figure 5d) are structured into comprehensive decisions including binary fault detection results, quantified maintenance recommendation scores, associated confidence metrics, and explanatory text descriptions. This output format ensures that conservation practitioners can validate system recommendations, effectively bridging the gap between algorithmic detection capabilities and expert judgment requirements.

The complete rule base contains 27 comprehensive rules covering all possible input combination scenarios, with confidence weights assigned through combined expert assessment and empirical validation processes (

Table 2). This exhaustive rule coverage ensures consistent decision-making across all operational parameter combinations while maintaining alignment with professional conservation practices.

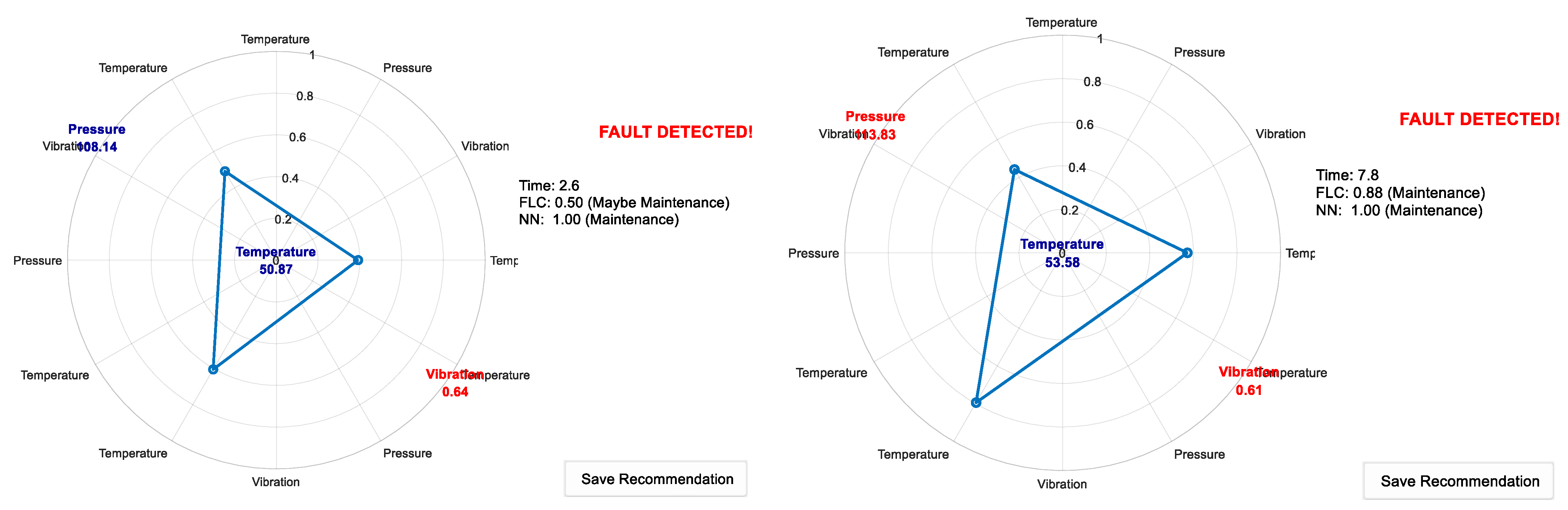

3.3. Integrated Hybrid System Architecture

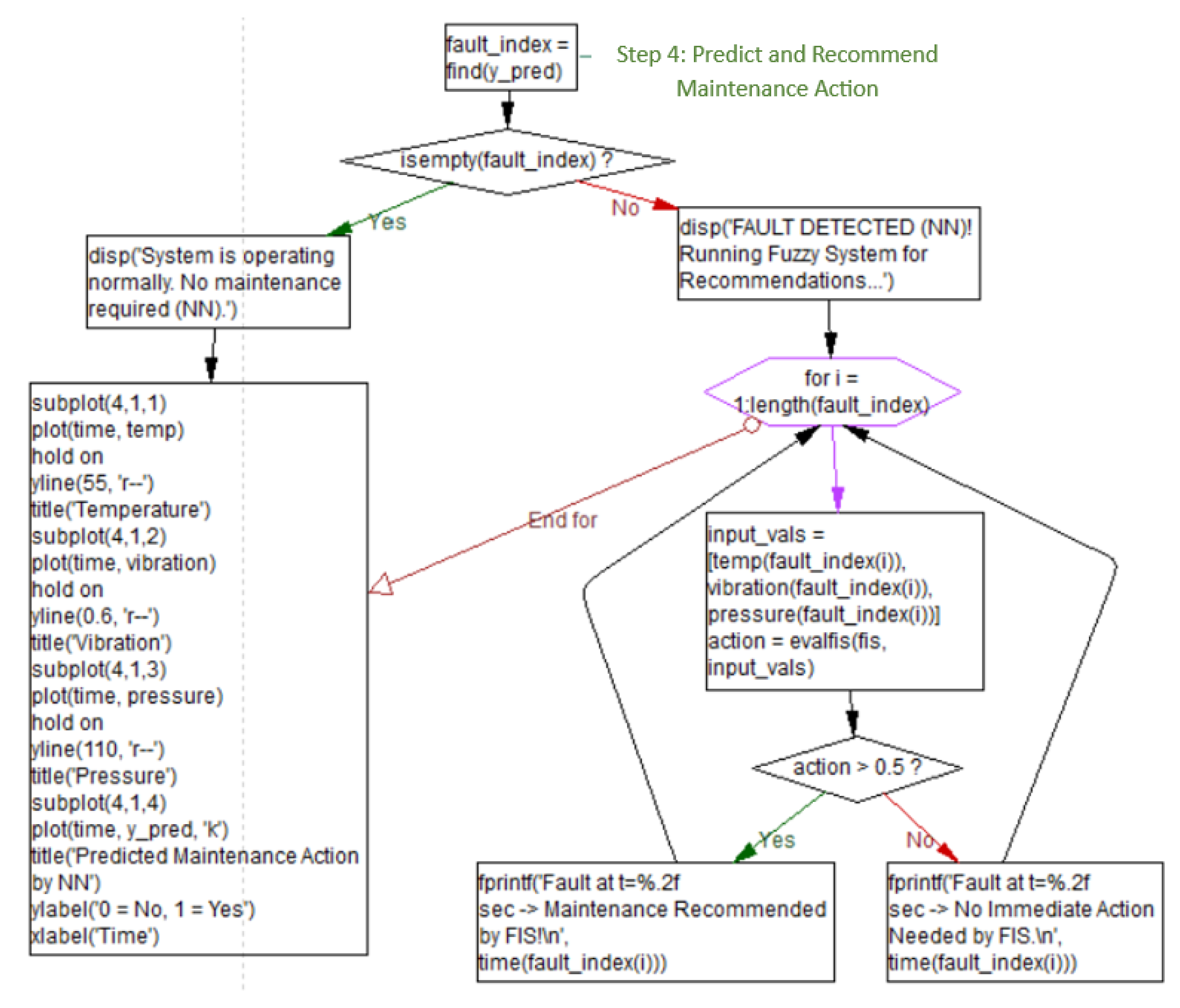

The hybrid system proposed implements sequential integration, ensuring predictive accuracy from neural network analysis is systematically combined with fuzzy logic interpretability (

Figure 6). When neural network output exceeds the predetermined classification threshold (τ = 0.5), the FIS module is activated to generate specific maintenance recommendations based on current sensor conditions.

The data flow architecture processes real-time sensor streams through sequential computational stages: data acquisition, preprocessing and normalization, neural network classification, conditional fuzzy inference activation, and final decision generation. Parallel preprocessing operations minimize system latency while sequential decision logic preserves consistency and reliability of maintenance recommendations.

Hybrid system outputs are structured into comprehensive decisions including binary fault detection results, quantified maintenance recommendation scores, associated confidence metrics, and explanatory text descriptions. This output format ensures that conservation practitioners can validate system recommendations, effectively bridging the gap between algorithmic detection capabilities and expert judgment requirements.

Thus, this proposed hybrid FF-NN-MFIS overcomes the fundamental limitations of standalone computational approaches. Neural networks alone provide superior predictive accuracy but lack decision transparency, while fuzzy systems offer interpretable reasoning but demonstrate reduced precision in complex pattern recognition tasks. Through systematic integration of both technologies, this approach delivers accurate fault detection and interpretable maintenance recommendations that align computational performance with conservation decision-making requirements and support sustainable, resource-efficient maintenance strategies.

5. Integrated Hybrid System Evaluation

5.1. Multi-Run Performance Analysis

The hybrid system evaluation employs rigorous statistical methodology conforming to machine learning best practices [

29]. Five independent runs were conducted with randomized data initialization, stratified random train/validation/test splits with data-dependent resampling, re-initialization of FF-NN weights via Glorot uniform distribution [

30] for each run, a fixed fuzzy rule base (27 identical rules across runs) to isolate FF-NN variability, and identical hyperparameters: learning rate η = 0.01, L2 regularization λ = 0.001, early stopping patience = 20 epochs.

For statistical interpretation (

Table 4), mean (Mean) and standard deviation measures (SD) are used to reflect sample standard deviation across

n = 5 runs. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using t-distribution critical values (t

0.025,4 = 2.776) appropriate for small samples, reflecting the conservative nature of reporting system performance with limited replication. Coefficients of variation (CVs) indicate relative stability—accuracy CV = 0.66%, energy CV = 3.79%—demonstrating robust performance despite initialization variability. The cross-validation stability metric (Cohen’s κ) > 0.91 across all runs indicates consistent classification behavior independent of data effects.

5.2. Feature Importance Analysis

Feature importance analysis conducted through systematic perturbation of input variables reveals the differential contribution of sensor modalities to fault detection performance. Temperature emerges as the dominant fault detection driver, accounting for 60.6% of variance contribution in classification decisions. Pressure serves as a secondary indicator, contributing 36.7% to the predictive model. In contrast, vibration demonstrates a negative correlation with fault detection accuracy, contributing −2.8% to overall variance, suggesting limited independent predictive value in the heritage building monitoring context examined. This hierarchical structure of feature importance indicates that thermal and pressure parameters constitute the primary drivers of fault detection decisions, while vibration measurements function primarily as confirmatory signals rather than independent fault indicators. The negative contribution of vibration may reflect noise sensitivity or context-specific characteristics of the synthetic dataset, where mechanical degradation patterns were less predictive than thermal stress and pressure anomalies.

5.3. Comparative Performance Analysis

Systematic comparison between standalone FF-NN and hybrid FF-NN-MFIS architectures reveals fundamental trade-offs inherent in balancing predictive accuracy with interpretability requirements. The standalone FF-NN, evaluated on a realistic fault rate of 24.50%, achieved accuracy in the range of 95–96% with corresponding recall of 95–96%, demonstrating superior fault detection sensitivity through continuous function approximation capabilities. However, this high performance occurred at the expense of limited interpretability, as the neural network’s internal representations remained algorithmically opaque to conservation professionals, requiring transparent decision justification.

The hybrid FF-NN-MFIS, evaluated under a fault-dominant rate of 62.40% to establish meaningful fuzzy rule boundaries, achieved mean accuracy of 94.3% with recall of 90.3% on the standard test set. Critically, recall declined substantially to 47% under fault-dominant evaluation scenarios, revealing a fundamental limitation in the hybrid architecture’s ability to detect borderline fault conditions. This performance degradation was accompanied by enhanced interpretability, quantified at 86.2%, reflecting the MFIS module’s provision of transparent, rule-based decision logic accessible to conservation practitioners.

The substantial recall reduction from 96% to 47% in fault-dominant scenarios illuminates a critical architectural limitation. The rigid fuzzy rule structures constrain detection capabilities for borderline cases where fault manifestation lies along continuous gradients rather than discrete categorical thresholds. The MFIS architecture, operating with fixed linguistic partitions, assumes that system behavior can be discretized into stable categories defined by membership function boundaries. This assumption proves inadequate for capturing subtle fault patterns that emerge through complex interactions between temperature and pressure parameters. Consequently, the fuzzy system systematically misclassifies borderline conditions as non-fault states, contributing to elevated false-negative rates that compromise system reliability in safety-critical applications.

The architectural trade-off analysis further reveals structural impediments to optimal performance. While the FF-NN, through its continuous function approximation capability, naturally accommodates subtle fault patterns distributed across the feature space, the MFIS enforces symmetrical rule coverage across all input features. This symmetric treatment implicitly assigns disproportionate importance to vibration despite feature importance analysis demonstrating minimal independent predictive value. The equal weighting across features dilutes the influence of temperature–pressure interactions that the FF-NN learned to prioritize as decisive fault indicators through gradient-based optimization.

Furthermore, the sequential hybrid structure introduces a fundamental decoupling between learned neural representations and symbolic fuzzy interpretations. The neural component generates latent feature outputs encoding complex non-linear relationships subsequently interpreted by rigid fuzzy membership functions not derived from the same representational space. This architectural disconnect creates an impedance mismatch between the continuous neural output space and discrete fuzzy linguistic categories. Without adaptive tuning mechanisms for membership functions or rule consequents based on neural network learning, the fuzzy module operates as a static filter rather than an adaptive integrator of neural output. This filtering effect systematically suppresses weak but potentially significant anomaly signals that fall within fuzzy boundary regions, explaining the observed recall degradation in fault-dominant evaluation scenarios.

5.4. System Advantages and Limitations

The hybrid neuro-fuzzy architecture demonstrates several distinct advantages alongside significant limitations that constrain its applicability in heritage conservation contexts. In terms of advantages, the system achieves enhanced interpretability through the MFIS module’s provision of transparent, human-readable decision logic that aligns with conservation professional requirements, quantified through an interpretability score of 86.2%. This transparency facilitates professional validation of automated recommendations, addressing a critical barrier to AI adoption in conservation practice. Additionally, sequential processing architecture enables multi-level validation of maintenance decisions through both statistical pattern recognition in the neural component and expert rule confirmation in the fuzzy component, providing redundant verification pathways that enhance decision confidence. The explicit rule-based reasoning structure supports regulatory compliance requirements by producing audit trails that document decision rationales, thereby facilitating integration into existing facility management protocols where accountability is essential. From a computational perspective, the system demonstrates operational efficiency with a total decision latency of 71.8 ms (±1.32), enabling real-time monitoring applications without requiring specialized hardware acceleration.

However, these advantages must be weighed against substantial limitations that constrain system deployment in certain contexts. Most critically, the reduced fault sensitivity evidenced by recall degradation from 96% in the standalone FF-NN to 47% in fault-dominant hybrid evaluation scenarios indicates the system is unsuitable for safety-critical applications where missed faults risk irreversible damage to cultural assets. The fixed 27-rule architecture lacks adaptive learning capabilities to refine decision boundaries based on operational experience, preventing continuous improvement through deployment feedback that characterizes modern machine learning systems. The symmetric rule coverage creates feature weighting misalignment with empirical feature importance distributions, where temperature contributes 60.6%, pressure 36.7%, and vibration −2.8% to fault detection variance, yet fuzzy rules treat all features with equal structural prominence. Finally, validation reliance on synthetic sensor data limits confidence in performance metrics under actual industrial conditions, where sensor noise characteristics, environmental variability, and fault pattern distributions may differ substantially from simulated scenarios, potentially affecting both accuracy and interpretability in operational deployment contexts.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This research presented a hybrid neuro-fuzzy framework for proactive maintenance in cultural heritage conservation, addressing critical gaps in interpretability, predictive accuracy, and decision transparency. The sequential integration of feedforward neural networks and Mamdani-type fuzzy inference systems demonstrates that complementary AI architectures can balance computational performance with professional validation requirements essential in conservation contexts.

The experimental evaluation across five independent runs established quantitative performance benchmarks demonstrating the hybrid system’s capabilities and inherent limitations. The system achieved mean fault detection accuracy of 94.3% (±0.62%) with precision of 92.3% (±0.78%), accompanied by an interpretability score of 86.2% (±0.73%) that quantifies the system’s success in providing transparent decision logic accessible to conservation professionals. Operational efficiency metrics reveal total decision latency of 71.8 ms (±1.32), confirming suitability for real-time monitoring applications. Feature importance analysis revealed temperature as the dominant fault detection driver, contributing 60.6% of classification variance, followed by pressure at 36.7%, while vibration demonstrated a negative contribution of −2.8%, indicating thermal and pressure parameters constitute the primary decision-making signals in heritage building monitoring contexts.

However, these performance achievements must be contextualized within significant architectural trade-offs that constrain system applicability. The hybrid system achieves enhanced interpretability at a substantial cost of reduced fault sensitivity, evidenced by recall declining from 96% (standalone FF-NN) to 47% under fault-dominant evaluation scenarios. This performance degradation stems from rigid fuzzy rule structures that constrain detection capabilities for borderline cases where fault manifestation occurs along continuous gradients rather than discrete categorical thresholds. The practical implications delineate clear deployment boundaries: the current implementation proves unsuitable for safety-critical heritage applications due to a pronounced tendency to miss subtle faults, but provides significant value for applications where decision transparency, professional validation, and regulatory compliance constitute primary requirements.

Adaptive fuzzy integration represents the most critical opportunity for improvement, requiring mechanisms for learning or tuning fuzzy rules from neural representations rather than enforcing static expert-defined structures. Promising approaches include extracting fuzzy rules directly from trained neural networks using rule extraction algorithms. Real-world validation through integration of authentic operational data from heritage sites across diverse climatic and cultural contexts would enable performance assessment under actual industrial conditions, calibration of site-specific threshold parameters, and systematic evaluation of generalization capabilities across Gothic cathedrals, museum environments, and archaeological sites.

Enhanced temporal modeling capabilities through recurrent neural network or Long Short-Term Memory architectures would capture temporal dependencies enabling prediction of degradation trajectories rather than instantaneous fault classification, while feature-weighted fuzzy systems with asymmetric rule coverage could align fuzzy reasoning with empirical feature importance distributions. Sustainability assessment through comprehensive lifecycle analysis quantifying energy consumption profiles, material impacts, and resource efficiency comparisons with traditional reactive maintenance would support responsible technology adoption decisions. Cross-cultural standardization through establishment of evaluation protocols defining interoperability standards and shared databases of fault patterns would enable objective benchmarking across diverse AI architectures and heritage contexts, accelerating field advancement through cumulative knowledge development.

This research demonstrates that the accuracy–interpretability trade-off in AI systems for heritage conservation is not insurmountable but requires careful architectural choices aligned with application-specific priorities and institutional contexts. For conservation environments where decision transparency, professional validation, and regulatory compliance constitute paramount requirements, hybrid neuro-fuzzy approaches offer viable pathways despite reduced fault sensitivity compared to pure neural network implementations. The explicit quantification of performance trade-offs through rigorous multi-run evaluation provides empirical foundation for practitioners to make informed technology selection decisions based on their specific operational requirements, risk tolerances, and technical capabilities rather than pursuing maximum accuracy regardless of interpretability costs.

Ultimately, successful deployment of AI in cultural heritage conservation depends not solely on maximizing predictive accuracy metrics but on developing systems that heritage professionals trust, understand, and can effectively integrate into established conservation workflows. The hybrid approach presented here advances this goal by demonstrating that interpretable AI for heritage preservation is achievable through thoughtful architectural design balancing complementary computational paradigms. The quantitative documentation of trade-offs provides a foundation for continued research investment in adaptive hybrid systems that can preserve interpretability while approaching the fault detection capabilities of pure neural network implementations, ultimately serving the fundamental mission of safeguarding humanity’s cultural legacy through intelligent, transparent, and trustworthy technological solutions.