Abstract

Cities are constantly transforming and, consequently, attracting efforts from researchers and opportunities to the industry. New transportation systems are being built in order to meet sustainability and efficiency criteria, as well as being adapted to the current possibilities. Moreover, citizens are becoming aware about the power and possibilities provided by the current generation of autonomous devices. In this sense, this paper presents and discusses state-of-the-art transportation technologies and systems, highlighting the advances that the concepts of Internet of Things and Value are providing. Decentralized technologies, such as blockchain, are been extensively investigated by the industry, however, its widespread adoption in cities is still desirable. Aligned with operations research opportunities, this paper identifies different points in which cities’ services could move to. This also study comments about different combinatorial optimization problems that might be useful and important for an efficient evolution of our cities. By considering different perspectives, didactic examples are presented with a main focus on motivating decision makers to balance citizens, investors and industry goals and wishes.

Keywords:

smart cities; digital cities; blockchain; citizens; sustainable development; IoT; internet-of-value; information and communication technologies; mobility Key Contribution:

Highlights the importance of technology for mobility and the potential it brings for citizens in the scope of the wave of innovation discussed within smart cities. This study reinforces how computational intelligence allows precise cities’ decision-making. Blockchain as a tool for promoting trust, lower costs, transparency and exchange of value on services used by citizens.

1. Introduction

Aligned with machines’ advancement and the new generation of personal devices, cities are evolving into a new paradigm called Smart Cities (SC) [1]. This evolution, closely related to equipment embedded with techniques from the field of Computational Intelligence (CI), is occurring in urban and rural areas. In addition to promoting decentralization of the current system, these new cities’ paradigms open doors for different autonomous agents, devices with CI capabilities, to optimize and manage their own interests. A complex decision-making scenario has been emerging based on historical data and an increasing potential of solving mathematical problems. While each of these software-based systems optimizes specific goals, simulations with multi-agent scenarios [2,3] should focus on improving overall performance. While this combination of technologies emerges, there is a huge trend moving to decentralized solutions, such as those based on Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLTs). The hidden layer behind the intelligence of these selfish agents and decentralized entities is the core of the future Smart and Digital Cities [4], which will be presented along this paper.

The expected outcomes of current transformations encompass systems that should reach favorable agreements, considering citizen opinions and participation of all involved entities. However, coordinating these agents handling a big volume of historical and real-time information [5] usually leads to the resolution of combinatorial optimization problems [6,7], which are undoubtedly a challenge for modern societies and technological development. In this sense, a multi-criteria view of this transition [8], aligned with the management of these emerging decentralized cities [9], should be carefully considered to address different stakeholders’ perspectives.

It is noteworthy that connecting the dots between what the academy and industry have been doing, and how to take profit from this previous knowledge, may save time and create pillars for future implementations. Since investments and the boom of novel devices are usually sponsored by the private sector, which is usually profit-driven, we emphasize the importance of taking into account all involved partners wishes, which would contribute to a progressive and holistic development [10,11,12].

Blockchain based technologies are used not only for enhancing trust between parties, but also because it has the potential to reduce costs [13]. In this sense, a match between an emerging technology and private interests is evident. In particular, cities’ mobility [14] and the future of the transportation systems are often one of the main concerns when talking about SC [15]. Zhuadar et al. [16] emphasized a next wave of SC intelligent systems, in which humans’ ability to connect with machines is advocated. This ability mentions the possibilities of implementing operational systems that connect citizens to smart equipment, mostly embedded with Internet of Things (IoT) capabilities [17]. Nowadays, we can add this IoT design with the concepts of Internet of Value (IoV) [18,19], which combines the potential of IoT with value transfer, mostly assisted by smart contracts designed with decentralized and semi-decentralized technologies such as blockchain [20].

In summary, the main points that will be highlighted along this paper are:

- (i)

- technological solutions that will be used in the digital cities transportation environment, both for the public and private interest;

- (ii)

- blockchain based technologies for promoting distributed trust on transportation systems;

- (iii)

- consider social aspects, highlighting how citizens are now interacting with the transportation services offered within the cities, such as carpooling, smart parking, and alternative transports.

- (iv)

- discussions about the possibilities that CI inspired tools have been offering for the future of our cities, pondering a trade-off between technology and quality of life.

Ultimately, this overview paper expects to contribute with readers to:

- (i)

- understanding some of the current transportation systems that are reality in some parts of the globe, as well as envisioning possibilities and technologies that might come to;

- (ii)

- creating awareness among citizens, researchers, teachers and students about the importance of the transformations that are occurring in urban environments, aligned with the SC paradigms;

- (iii)

- introducing state-of-the-art concepts about decentralized solutions, such as those using blockchain;

- (iv)

- highlighting the importance of considering multi-objective optimization problems and multi-criteria analysis;

- (v)

- motivating the academy and the industry to develop and work towards “fully” distributed and “transparent” approaches, in order to balance the goals of different autonomous agents;

- (vi)

- understanding the potential that DLT technologies have in removing the trust barriers in Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Transportation systems.

In order to achieve the desired impacts, the remainder of this paper is organized simply. First, it discusses some current real applications and undergoing studies on operational research and high-performance computing in Section 2. Trends for transportation systems are pointed out inside the scope of Section 3. Finally, final considerations and future research directions are presented in Section 4.

2. The Search for an Optimized Urban Transportation Ecosystem

As mentioned by Derrible and Kennedy [21], urban transportation planning and network design is a problem that has been faced by society from the street patterns of the Roman Empire [22] to the current computational intelligence systems of our present days [23]. Logistics and urban planning problems encompass crucial aspects that can guide efficient cities’ functioning and citizens life quality, such as modeling and designing in order to increase pedestrian mobility [24]. In this section, we are going to highlight advances that the optimization has been bringing for an efficient use of the transportation systems.

2.1. Graph Modeling

The topological/geometric nature of transportation systems and their dynamics motivates studies focused on graph theoretical models. Derrible and Kennedy [21] revise that graph theory dates back to 1741, when mathematician Leonhard Euler had some insights about the “The Seven Bridges of Königsberg”, a problem that can be succinctly described as follows: find, if possible, a tour that traverses every edge of the graph exactly once and returns to the starting point.

Modeling the novel class of transportation problems in a efficient manner, mostly dealing with huge amounts of information, increases the chance to achieve more efficient solutions, in accordance to what decision makers are looking for. For this purpose, we highlight the use of graph clustering techniques, as in [25,26], since such tools can connect these new problems with works already addressed in the literature. For example, in [25], the problem of grouping parts to be produced and the machines that will process such parts into homogeneous cells is studied so that the number of faults (part-machine pairs that do not have relation) is minimized. The motivation for such a study comes from industrial planning and development, where optimizing transportation of parts between industrial parks is highly desired. In [26], efficient algorithms to solve the cluster editing problem (that consists of adding and/or removing the minimum number of edges in order to transform the input graph into a disjoint union of complete graphs or “clusters”) have been described by the authors, motivated by applications that demand grouping data with high degree of similarity, while discarding spurious information. Such “clustered solutions” can be viewed as an attempt to cover large urban agglomerations by homogeneous, self-governing small cells that can work autonomously. A scatter search was designed by Chebbi and Nouri [27] to solve a graph with stations and nodes, for moving jointly persons and goods in urban areas, in order to minimize energy consumption within the context of smart cities.

Multi-modal transportation systems [28] are interesting examples for highlighting the actual complexity of urban transportation. This family of problems also can cover the locomotion for motor profile (reduced mobility). This kind of optimization can be dealt within the scope multi-objective optimization [29,30]. As an example, the Minimum Coloring Cut Problem (MCCP) is defined as follows: given a connected graph G with colored edges, find an edge cut of G (a minimal set of edges whose removal renders the graph disconnected) such that the number of colors used by the edges in is minimum. A potential application of the MCCP is in transportation planning systems, where nodes represent locations served by bus and edge colors represent bus companies. In this case, a solution of the MCCP gives the minimum number of companies that must stop working in order to create pairs of locations not reachable by bus from one another. Such application is more suitably modeled by allowing a multigraph as the input of the MCCP, since two locations can be connected by bus services offered by more than a single company.

Furthermore, the so-called interruption graphs can be considered in post-disaster logistics, a problem of great importance for different events that may occur in urban centers. These approaches are suitable to assist with the human decision-making process, in particular, when huge disasters happen, such as the 2017 Irma hurricane. In order to promote better integration with citizens, it is also suggested to study and develop new techniques for processing huge graphs, using high-performance computing, in order to verify interaction between citizens, cities and social networks.

2.2. Smart Routing Problems: Multi-Objective Optimization

Vehicle Routing Problems (VRP) [31] cover a wide variety of problems faced by modern society, both in the industry and public sector. From a simple route apparently taken by a postman [32] in order to deliver packages to a set of customers, humans have been facing complex decision-making scenarios in which computers’ assistance has been shown to be crucial. These challenges are now being solved without users realizing how it indeed happens. In this sense, we pinpoint the open opportunities for innovative applications that should carefully consider the users’ profiles, wishes and desired goals. Furthermore, due to the current advances of many-objective visualization tools [33,34], we expect that data visualization on complex problems will start to turn into common tools used by the industry and decision makers.

Recently, an optimal trip system was claimed by Dotoli et al. [35]. At this point, we highlight the discussion about what is actually an optimal trip in the context of a multicultural SC? While some will surely enjoy specific paths (with particular amount of light, temperature, wind, etc.), others will opt for the fastest or the less noisy. In addition, the specific types of vehicles and mobility systems that each person uses is another point to be added to this multi-objective scenario [36,37]. Furthermore, when public transportation systems are considered, cost and speed is another trade-off handled when citizens use transport integration [38]. The resolution of problems in the scope of green logistics is under discussion not only by the academia [39,40,41,42] but also by the industry [43,44], which basically involve different models for calculating the cost of the routes, involving other components in the objective function equation, such as carbon emissions [45,46]. Discussions under the scope of autonomous also involve batteries and fuel cell based equipment [47]. In this sense, there is a trend in researching more sustainable transports connected with the achievement of higher profits [48], which are concepts that should match for the achievement of a widespread adoption by the industry.

Let us consider an undirected graph , where and represent, respectively, the vertices and edges of a given graph G. Da Silva and Ochi [49] designed an Adaptive Local Search Procedure for tackling a travelling salesman problems in which the rented car could be returned or not at the nodes from a graph G. In this sense, the graph could contain dynamic points in which the users might spontaneously decide where to deliver the vehicle regarding a set of stochastic aspects. It is noteworthy that this problem can be adapted for dealing with several rented cars and car sharing systems on urban scenarios. Doppstadt et al. [50] considered routes that could be optimized according to different operating modes, such as: pure combustion mode, pure electric mode, charging mode (in which the battery is charged while driving with the combustion engine) and a boost mode (in which combustion and electric engines are combined for the drive). However, other points are still open to be considered, such as modes in which the vehicle would charge from: breaks, solar radiation or even rapid winds streams. The study of Quercia et al. [23] also provides an idea on how routing can be considered under many different points of view, defining routes in terms of “smellwalks”, in a study where participants followed different smellscapes and asked to record their experiences.

2.3. The Role of Metaheuristic and High-Performance Optimization

Metaheuristics are a family of methods that dates back the 1950s with the advent of Alan Turing publishing a study called “Obvious connection between machine learning and evolution”, focused on an effort to find solutions to problems inspired by behaviors presented in the nature. In addition, Design by Natural Selection [51], written by Dunham et al. in 1963, presents some descriptions about a method that deals with exploration–exploitation concepts [52].

While some combinatorial problems can be solved with exact algorithms [53], NP-hard problems have a exponential nature in which the size of the problem strongly affects the time in which optimal solutions can be obtained. Added to this, the sea of big-data that is currently available in modern cities makes the decision-making scenario [54] a big trade-off between using computational resources and providing a solution as quick as possible. For this reason, this current paper emphasizes and motivates the use of metaheuristic inspired techniques [55]. One of the core of several trajectory search based Metaheuristics is the use of Neighborhood Structures [56] and, consequently, local search mechanisms [57], which have the potential of proving optimality in some specific cases. For this purpose, efficient high-performance techniques have been suggested for tackling this problems, such as Graphics Processing Units [58,59].

3. Cities Transportation Trends

This section has the goal of highlighting trends based on academic and industrial perspectives. For this purpose, in order to analyze the trends about cities’ transportation, a bibliometrics search on Scopus Database was carried out.

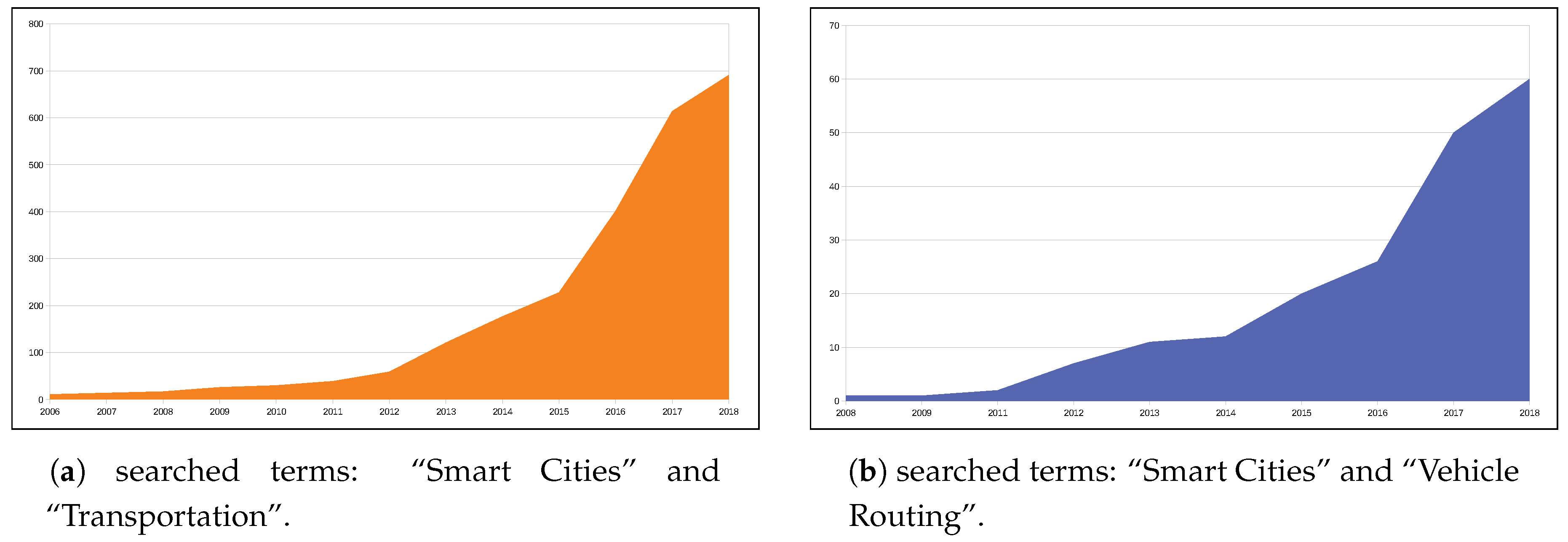

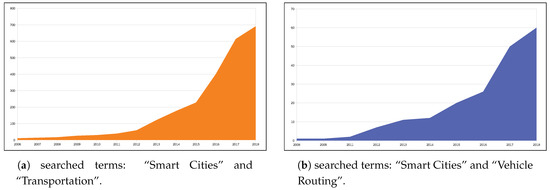

As can be noticed in Figure 1a, the number of publications mentioning transportation systems and SC have been increasing over the last few years. Figure 1b also shows an increasing number of published papers related to the terms SC and Vehicle Routing.

Figure 1.

Raw number of published documents (information extracted from Scopus on 20 June 2019).

However, in terms of the absolute values reported in graphs depicted in Figure 1, one can make conclusions about the potential that these guidelines still have for the next decade. Some of the novel transportation systems are already becoming reality, and others are still being designed. Furthermore, since 2005, more than 12,000 patents (considering a search done with the terms “Smart Cities” and “Transportation” on Scopus database) have been found, which highlight the efforts made by the industry and the academia in order to find alternative technologies for more profitable and efficient transportation solutions.

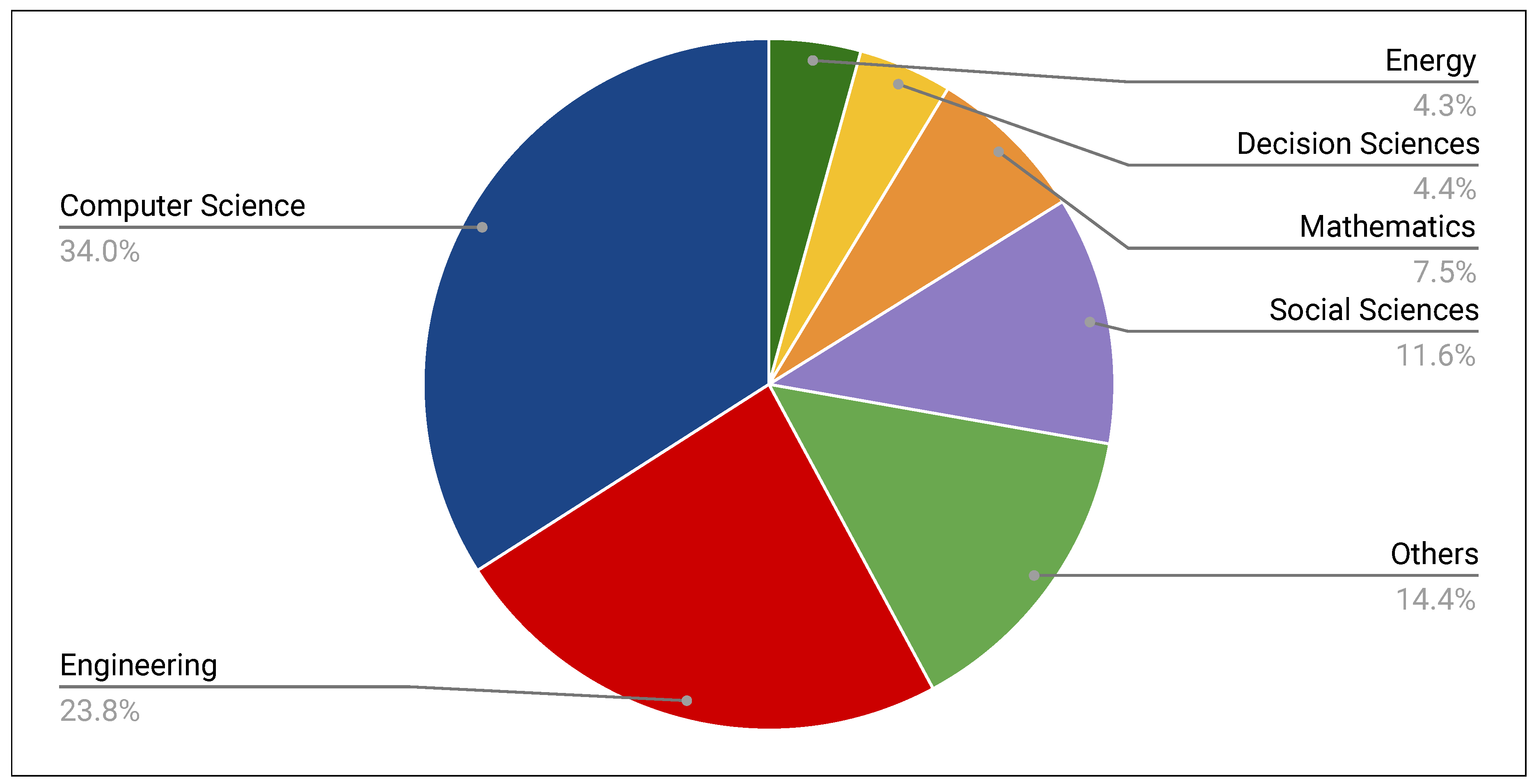

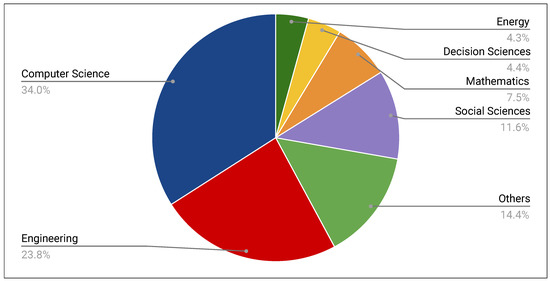

In addition, it was possible to analyze that these two keywords are addressed mainly in the fields of Computer Science, Engineering and Social Sciences, following from areas such as: Mathematics, Decision Sciences, Energy, among others. The interest in these terms among different research areas is depicted in Figure 2. Taking a brief look at the history, it can be noticed that smart cities studies started with a technological perspective, and now it is being spread among other research areas, with a significant percentage of publication in the field of social science [60].

Figure 2.

The rise of the interest in SCs’ transportation systems by different field of knowledge (search was done on June 20th, 2019 on the Scopus database).

3.1. Mobility and Citizens

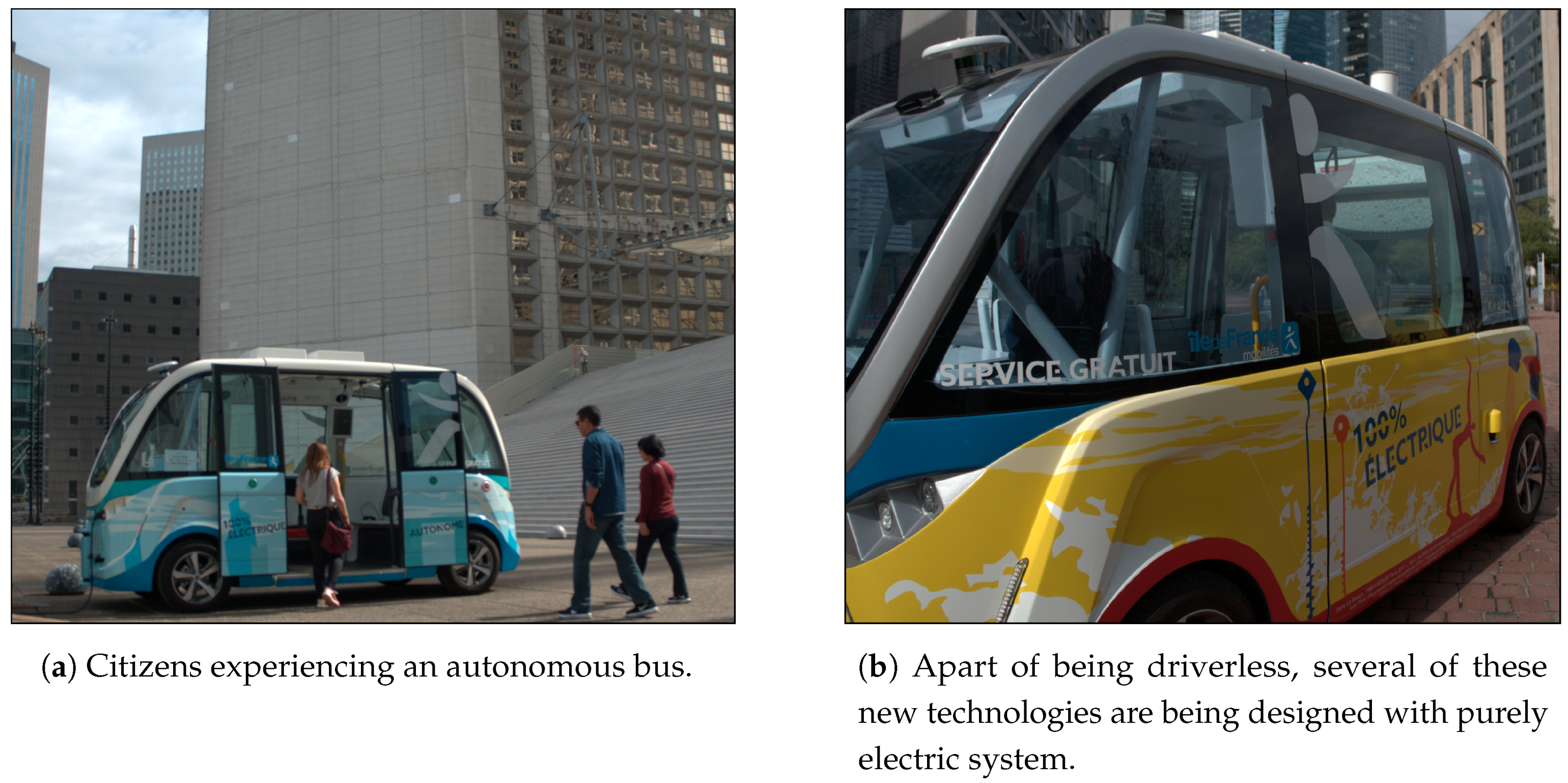

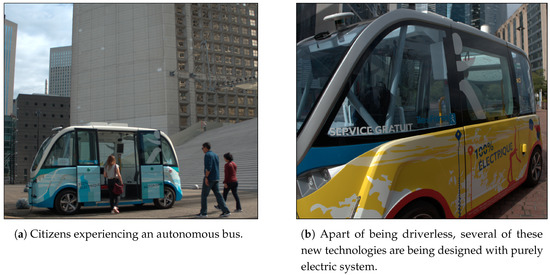

A technology becomes part of society when those who use it do not realize its presence, such as concepts surrounding ubiquitous computing [61]. Some authors discussed the growing possibilities of pervasive Artificial Intelligence [62] in SC [63]. A similar idea applies to rules/laws/policies; for example, smoking inside closed places is no longer an issue noticed or missed. For instance, Figure 3 shows a driverless bus running in the technology center in La Défense, Paris. In the future, citizens may not even notice the amount of technology embedded into cities’ transports. Thus, technology can even be part of the cities without a daily perception about it.

Figure 3.

A driverless bus in La Défense, Paris (© Thays A. Oliveira, CC BY-SA 4.0).

If one considers the current possibilities that the decentralized transportation systems are promoting, we may notice an omnipresent interaction with citizens’ interests. As an example, the actual route that a private car can take (like when you call an Uber) can be chosen according to clients’ desire. This example reinforces the ability that Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) has with end-users, providing the option of choosing the most suitable transportation system that fits personal beliefs [64]. Interacting with citizens in order to guide their way of moving around is becoming a reality for those which are living in modern urban cities [65,66]. The constant interaction by means of online services proportionate the opportunity of picking different routes for reaching a destination considering real-time measured data. In this sense, different maps’ services provide possible routes that use different types of transportation and forecast the arrival in the final destination within an expected time limit, considering stochastic information about traffic. Improving the interaction between citizens and public/private transportation systems represents a challenging issue. The main core of this problem relates to the design of systems that interact in a transparent, fast and reliable platform. Blockchain based technologies can be used for promoting transparency [67] and also reducing costs [68] (as will be emphasized in Section 3.5), while the other aspects related to data sharing may come consequently from other advocated points of the SC concepts.

On the other hand, we highlight the importance that urban policies have in order to regulate old transportation systems, such as noisy vehicles and pollutants’ emissions, even considering the fact that electric based transportation systems are not more sustainable than fuel based ones since the problem turns to where energy is really being produced. Inside cities, it is quite obvious that less pollution will be emitted by those electric systems; thus, it is a consensus that urban environments will become more pleasurable. Regarding this aforementioned reasoning about where energy is really produced, it is noteworthy that Smart grids [69,70], in particular, microgrid systems [71], will play the role of decentralizing energy production. In addition, citizens are another key point that will become part of these smart systems, since energy consumers are also becoming suppliers [72,73,74].

Bike sharing comes to cover some of the cities’ public transportation failures and has become a common means of transport in urban centers [75]. An efficient shared bicycle system includes stations in areas of greater demand, pondering a trade-off between cost and benefits of each station. A combinatorial optimization problem of placing such stations along the cities is crucial [76], being advocated as a crucial tool for helping urban managers. Other optimization problems were dealt in order to determine the optimal number of bikes in each station [77], most of them handling stochastic variables and modeling. Other works in the literature dealt with the simulation of such scenarios [78].

Alternative electric based transportation systems such as powered two-wheelers [79], e-scooters [80] and e-bikes [81] are now constantly being used inside urban scenarios due to their advantages when parking and great autonomy up to 40–60 km per charge, providing access to a new class of users [82,83]. This equipment is also being used for deliveries, highlighting the fact that combustion vehicles can be replaced by electric based transportation systems [84].

Real-time solutions for managing bike sharing systems have also been investigated and proposed. For dealing with such scenarios, distinct methodologies can be applied for finding empty stations, such as: the use of soft sensors, the use of apps, as well as the use of drones. An innovative and didactic video has been edited by some of the authors of this current study and has been made available (Link to a didactic video about a bike sharing system, with different modern components (drones, renewable energy, online apps and sensors), in a Smart City, produced by some of the authors of this current study: https://youtu.be/KX7SndbHOe0).

3.2. Smart Parking

Parks have played an important role in urban areas since they “allow” the access to other facilities. In urban congested cities, anybody can observe that parking his/her car somewhere may be as difficult as moving in the traffic jam because of the lack of parking places. The amount of time to find a place to park, known in the literature as the cruising time, can be huge. Like a domino effect, random cars riding in circles across the city hoping to get a parking place within walking distance and ease of parking (as well as previously parked locations) continue to contribute to inefficient time/energy spending, to congestion and to air pollution. For this and other facts, several initiatives are aimed at reducing the number of vehicles in urban centers, so-called carless cities.

Recently, studies and cities policies have been analyzing impacts of several different strategies to reconcile parking and mobility, such as a reservation system for on-street parking [85]. IoT cloud-based intelligent car parking system was introduced by Ji et al. [86]. In an attempt to develop a required system within a university campus, Ganchev et al. [87] introduced a strategy using an info station based on decentralized autonomous agents sharing the data. Collective or specialized transportation is gaining momentum, as we highlighted in Section 3.1. At the same time, hybrid/electric vehicles can be idle for a fraction of the time. During these moments, smart parking arises [88] as a set of tools that can be connected with microgrid concepts, allowing vehicle batteries to interact with the power grid [89]. This represents a positive effect of such use, whereas a growing discussion has been pointing out these novel emerging vehicles systems as unsustainable due to their energy supply impacts [90,91].

SC policies have also been discussing how to regulate and control noisy vehicles, for example, with surveillance systems [92]. The number of entities that are communicating in these new SC environments is impressive, which is another factor that motivates the study of distributed approaches, such as multi-agent systems [93]. Other alternative transportation systems, such as the use of traditional and electrical bicycles, scooters, hoverboards and skateboards, involve different parking logistic problems that must be solved by managers of a city or companies that operate in the sector.

In an operational point of view, CI tools should try to find solutions that handle the following questions:

- (i)

- Where is the parking located that makes it easier access to activities [87]? What size should they have? What are the transportation systems that this parking will cover?

- (ii)

- How should these new operators (parking assistants) organize their routes to satisfy all demands at minimum costs?

- (iii)

- How can the price be evaluated to charge customers for this service?

- (iv)

- Is it better to have a flexible organization in which pickup and delivery of the cars may be done at any point, or a more rigid one where the pickup and delivery points are fixed stations similar to taxi ones (with the difference that, in this new station, cars will be picked instead of people)? Where can those parking assistant stations be located?

- (v)

- What is the system centered on? Citizens (target age, common local activities) or cost (greening techs and time savings)?

Questions (i) and (ii) have their resolutions linked with facility location problems, including a non-standard variant of the TSP, which can be solved using exact methods or metaheuristics (as pointed out in Section 2.3). The question (iv) falls into the class of VRP (pickup and delivery) with the additional constraints between a pickup and a delivery point, associated with a demand, an agent should park the customer car somewhere. The pricing problems (question (iii)) can make the service attractive or not, as well as considering forecasting mechanisms that act in the market with information of energy consumption, generation and price [94].

However, even considering the power of actual algorithms, no new organizational and CI system can be validated and implemented using only optimization techniques because many aspects are not considered, or, if included, they would lead to higher technical difficulties. For instance, we can highlight the following points to be considered: uncertainty on the congestion phenomenon; uncertainty on the customer plans (list of activities to perform); uncertainties on traveling times; and the effect of multiple similar demands on the traffic congestion.

Consequently, studies on multi-agent simulation (as we introduced in Section 3.4) are now a standard technique [95] used to understand what may happen if a new organization intervenes in a city life (including traffic, and environmental impacts). Taking into account that an urban area is a complex system, counter-intuitive consequences may occur which cannot be viewed simply by solving some optimization problems. Reference [94] also dealt with a parking selection problem in an SC scenario, their work uses a multi-agent flexible negotiation mechanism to address the parking space by taking into account the car owner preferences in locations, parking vendors’ preferences regarding car park occupancy and social city benefits.

The insertion of renewables is also in connection with electric powered transportation systems, in which new challenges arise. On the other hand, electric based vehicles require a different moving paradigm, in which they should be smartly charged. In this sense, power dispatching systems [96] are incorporating Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) in their daily schedules [97], creating a new wave of parking systems with electrical capabilities. There have been efforts of studies that tried to forecast and determine the optimal time for charging these vehicles [89,98]. In addition, multi-objective models are also being developed for pondering the different cost-emissions that V2G technologies may be able to reduce and balance [99]. The reduction of waiting times in the queues of fast charging stations has also been proposed using MAS, serving as the control strategy of the network [100,101].

3.3. Electric Based Transportation Systems

The insertion of electric and hybrid vehicles has been driving advances towards the use of renewable resources, and vice versa. One can say that, in view of the massive integration of Distributed Energy Resources (DER) with microgrids [93], green transportation systems [102,103] are boosting researchers to re-analyze solutions of classical optimization problems. Although the literature have been addressing some SC troublesome logistics, the integration of renewable resources has received little attention when dealt with in connection to urban planning problems. For example, when considering the relief of a city, vehicles can optimize their routes in the search of maximum energy efficiency [50]. However, several solutions focus only on classical obstacles, disregarding the current social context and the technological evolution that we have gone through. In view of these points, a new class of problems and possibilities set up new paradigms and challenges that demand more innovative solutions.

Moreover, the immense range of alternative electric transports that is emerging (skateboards, scooters, bicycles, monowheel systems and so forth) weighs in on considering possible logistics problem, beyond hybrid or pure Plug-in Electric Vehicle have [104,105]. Nonetheless, emerging technologies should be connected in our transportation system, such as roads with solar panels that might charge and assist this structure [66,106]. At this point, we highlight the open opportunities for managing vehicles in SC. Which point will the stakeholders balance in order to manage this system? Will it be guided by the amount of CO emissions balanced with traffic jam issues? Will the acoustic pollution affect the decision-making process? Undoubtedly, multi-objective optimization problems arise when this class of problems are being dealt with.

3.3.1. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Emerging Technologies

The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) [107], also known as Drones, or Unmanned Aircraft Systems, as transportation is reality in different sectors, from the pioneers’ military applications to daily goods transportation [108]. The affordability to low-cost sensors, such as those presented in our modern smartphones, has been motivating society towards innovative flying equipment.

A study held in Beijing [109] suggested an oriented information application for assisting drones with locating charging stations. Other works in the literature also study the use of different fuel options in Smart Cities operations [110]. Indeed, this kind of emerging application would be useful in the context of drones. While the electric grid, in particular mini/microgrid systems [98], may also use these news vehicles as storage units, they are also motivating their insertion into the core of the cities since the new economic scenario may be profitable for those that want to use their batteries during idle times. Recently, the work of Coelho et al. [108] considered the use of UAVs as transportation units, defining their routes in a multi-objective manner, taking into account charging points, batteries autonomy and different aspects that might be reality in a few years. Different patents are being registered related to the use of drones for transportation. The charging of e-vehicles needs to consider energy availability along their routes, which could also be assisted by UAVs on idle times.

3.3.2. Superconducting Based Technologies

Certainly, one of the most promising technologies of this century is the advent of superconducting materials [111,112,113]. These have unique physical properties that will propel human beings to understand and produce technologies with lower levels of interference and noise in their vicinity. Among them, a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID) [114] allows measurement of very small magnetic fields, with magnitude detection on the order of . These sensors also have high sensitivity in relation to the amplification of electrical or light signals. Conventional electronics, which use semiconductor and ferromagnetic materials, have already reached a satisfactory sophistication so far. However, certain problems can only be solved with the advent of superconductors, by using Josephson junctions in components such as SQUID. This extremely sensitive sensor allows the magnetic flux to be transduced into measurable electrical signals. This device is so sensitive that it can capture the magnetic field of human hearts and brains with great precision, perhaps this explains the great rise of superconductors in medical areas. When it comes to small-scale applications, superconductors are being used in biomedicine, metrology, geophysics, digital processing, devices and sensors [115,116,117]. As far as superconducting sensors are concerned, superconductors are already being used in various areas of human knowledge, from physicians, astronomers, to the military [118,119,120]. A widely publicized application of SQUID is magnetoencephalography, a technique that allows for mapping the magnetic fields generated by the brain activities through sensors that work in conjunction with SQUIDs.

By promoting greater robustness in quantum technologies, superconductors will bring a real scientific revolution in different areas, such as emerging transportation systems [121]. The latter face challenges that will be circumvented, such as fuel economy, environmental issues, overcoming the increased demand, among others. With the advent of superconductors applied for this area, different sectors related to transportation may see its benefits [122], such as high-speed trains; boat propulsion systems; and high-powered aircraft engines.

Although significant applications in electronic devices are still difficult because of the need for operation at low temperature, superconducting materials are already under development in very high integration circuits [123]. By reducing the dimensions of the components’ thermal dissipation is limited, requiring it to be cooled by liquid nitrogen or even liquid helium. In relation to efficient superconducting electric motors, they have been inserted into some specific transports, giving rise to a new generation of turbines, coils and, consequently, electric transport, airplanes, trains, cars and ships [124,125,126,127]. An example of transport in which the superconductors are employed refers to the Maglev train [128,129]; this levitates on the rails counting, basically, only with the resistance of the air-like force of friction. Thus, Maglev trains are faster than conventional trains because they float about ten inches above the rails on a “magnetic mattress” for a lower cost and greater safety than a conventional train. These are listed as one of the best means of transport for futuristic cities [130], and can reach speeds of the order of 600 km/h, mainly due to the elimination of conventional wheels, making the friction no longer a huge barrier. Of course, this technology will also receive attention with the recent advent of SC [131,132], which has been promoting researchers to idealize insights about possible future projects [133].

With regard to storage, there is still no efficient method for large volumes of electricity. The Superconductive Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES) [134] is a promising technology that has been applied in different transportation systems [135]. The main feature that motivates SMES use, apart from its apparently linear behavior regarding energy loss, is its quick response, enabling a huge possibility for quick charging on cities’ parking stations [135,136]. This system stores energy by a continuous flow in a superconducting coil. The stored relies on this superconducting coil that is basically a cryogenic with temperature below the critical superconducting temperature. A transportation system that relies on these batteries can quickly charge on sporadic stops, such as electric buses. Enterprises are already investing in this kind of technology [137,138], which will surely boost other real-world applications.

3.4. Decentralization via Multi Agent Systems

Multi Agent Systems (MAS) is a network of software agents that interact to solve problems that are beyond the individual capacities or knowledge of each agent, with either diverging information or diverging interests. MAS are quickly becoming reality given to the recent possibility of acquiring data from the various IoT based devices available in the market. In this sense, autonomous IoT agents facilitate common use of local controls, real-time tuning of control parameters, peer-to-peer negotiation protocols, automatic arming and disarming of control actions in real time, reacting and acting based on a variety of big-data. All that information is measured, processed, optionally shared, mined, forecasted, and used for guiding decision-making [139,140]. A conceptual model via MAS and IoT is usually applied through the following principles: inseparability, virtualization, decentralization, real-time capability, service orientation and modality [141,142].

Progress in mobile and ubiquitous computing is promoting work sharing between a large number of agents in an orchestrated and self-organized manner [143,144]. Regulators can act autonomously in this environment, interacting with any device in the system. For this purpose, generalist platforms should communicate in a standardized and trustful manner, providing certificates and proof-checking. All of the trust can surely be handled by using blockchain concepts (as emphasized in Section 3.5). A generic conceptual model for smart cities was illustrated in [95], highlighting how MAS and ICT can result in new generation businesses and interactions. Chen [145] proposes to delegate ambient devices through various machine-to-machine (M2M) communications. Marsa-Maestre et al. [146] developed a hierarchical arrangement of mobile agents able to personalize users’ needs. As should be noticed, with proper modifications, any task can be dealt in distributed manner [145], providing benefits such as improved scalability and trust.

An initial attempt to develop a car parking locator service, within a university campus, was done by Ganchev et al. [87], considering an info station based on MAS. In a subsequent work [94], an MAS flexible negotiation mechanism was developed, taking into account car owner parking vendors’ preferences and social city benefits. In recent studies, developing adaptive traffic signal control [147] was done by reinforcement learning agents. Each intersection can be controlled by a single independent agent which determines the light switching sequence. Prendinger et al. [148] developed the Tokyo virtual living laboratory traffic simulator based on autonomous vehicle agents’ interaction. Understanding road user interactions, using game theory concepts, was discussed for a scenario in Norway [149], composed of vehicles and pedestrians. Furthermore, an MAS based traffic simulation system [150] can assist autonomous vehicles in connection with VRP on dynamic scenarios fulfilled with uncertainties, in which high-performance techniques are also embedded for assisting the decision-making process. Machine learning algorithms are being extensively applied for traffic control [151] and using MAS is inevitable for reaching such complex agreements [152]. Reference [153] modeled a game theory application discussing car pooling profits and incentive expenses. The role autonomous devices with GPS capabilities can be used for achieving a more efficient and safe urban traffic [154,155,156,157]. An adaptive traffic signal control done with reinforcement learning agents was proposed in [147], in which each intersection is controlled by a single independent agent which determines the light switching sequence. It is noteworthy that each of these autonomous devices can solve different logistics problems for assisting their decision-making, in which the core of the problem solver can be in the cloud, on device, in a central or in a distributed manner.

The book “Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?”, of Sandel [158], mentions a multi-criteria scenario in which authorities decided to increase speed limit, even considering that more deaths would occur. This trade-off is undoubtedly an important point to be agreed on by the selfish agents that are crossing an intersection. A similar initiative is highlighted at a Brazilian online platform that compares maximum speed limits and traffic behavior (available online at https://www.hacklab.com.br/simulador-de-transito/).

3.5. Blockchain for Managing Cities’ Transportation Data and Contracts

Besides providing an introduction about the core concepts and ideas, the authors connect Blockchain and P2P transportation systems within the scope of digital cities, as well as present a draft of an innovative Smart Contract that could manage some components of a decentralized service for transportation.

3.5.1. The Core of the Blockchain and Smart Contracts

The Blockchain technology has been gaining attention since the appearance of Bitcoin cryptocurrency [159]. Despite hype applications on the financial sector, other vertical markets have been trying to integrate its features for different assets’ management. To satisfy different business needs, several Blockchain platforms have emerged concomitantly with solutions presented by other distributed ledgers’ technologies (DLTs) [160,161,162,163].

At a glance, the blockchain is a distributed network with enhanced security attributes, in which the P2P architecture and cryptographic keys compose a protocol that keeps the network reliable through automatic verification processes. One of its distinguishing characteristics is how the protocol reflects the way the network behaves when a new operation is requested. For this end, the consensus algorithm is responsible for managing who should append new values on the distributed database (ledger) and the possible conflicts that might arise. Another feature is that any interaction with the platform is designated as a transaction and is recorded on a new blockchain state.

Smart contracts are algorithms designed for being interpreted by specialized virtual machines, throughout its conversion to opcodes. Those virtual machines, usually, specifically designed for each blockchain project, often call precompiled scripts that optimize the calculus of commonly used functions. After being registered throughout a transaction, they are identified by a unique hash. In fact, in Bitcoin, NEO Blockchain and several other blockchain projects, the standard addresses that we often see are all smart contracts with a simple functionality of pushing a set of bytes and calling an opcode often known as a witness checker. This allows the creation of distributed applications (DApps) to serve different business demands [164,165].

However, Blockchain follows a long time evolution of distributed protocols’ technology. Section 3.4 highlighted decentralization via MAS, which has inspired the solutions focused on the Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) problems [166], discussed around the 1980s, and currently integrates important aspects of Blockchain consensus. Some Byzantine-like variations have been discussed over the years. For instance, the Practical BFT protocol [167] is celebrating 20 years now, and its outcomes have inspired Blockchain world consensus such as the Delegated BFT used by the NEO Blockchain [160].

Moreover, blockchains are also recognized by different network governance levels that imply how the ledger read/write access is made. This gets a classification from permissioned to permissionless, i.e., from more centralized to decentralized network, and it is used to compose a range of Blockchain platforms. Besides the more well known such as the NEO, EOS, Ethereum, and Bitcoin, there are other relevant platforms that focus the most on industrial applications of permissioned chains. Among them, we highlight that the NEO Blockchain is a pioneer high-performance library for developing smart contracts. It was the first Blockchain project to successfully run a public chain with the finality of one block. This means that information appending is finalized as soon as the majority of those involved in the consensus signed the information.

The diverse platforms available meet specific business application needs [168]. As a result, there are several DApps under development that cover the future transportation system, the electricity grid, and a variety of other service applications. For instance, considering smart grids [169], it is possible to manage Electric Vehicle (EV) recharging stations of different energy suppliers through a standard method of payment [170], in which the flow of money and service (the core of the IoV) would flow according to predefined rules. In addition, the use of cryptocurrencies to pay energy bills [171,172] or to trade electricity between citizens with a dedicated Blockchain platform [170,171,173] has the potential to expand the offer of different energy resources for fueling transportation needs.

Therefore, blockchain technology can be seen as a unique and innovative solution for everything that concerns trust between entities, which is reality in almost all interactions of public and private transportation systems. However, decision makers need to increase their awareness that the development of digital technology at a country-level scale may go at its own pace with respect to legal statements and partnerships to deal with the complexity of DLTs [174].

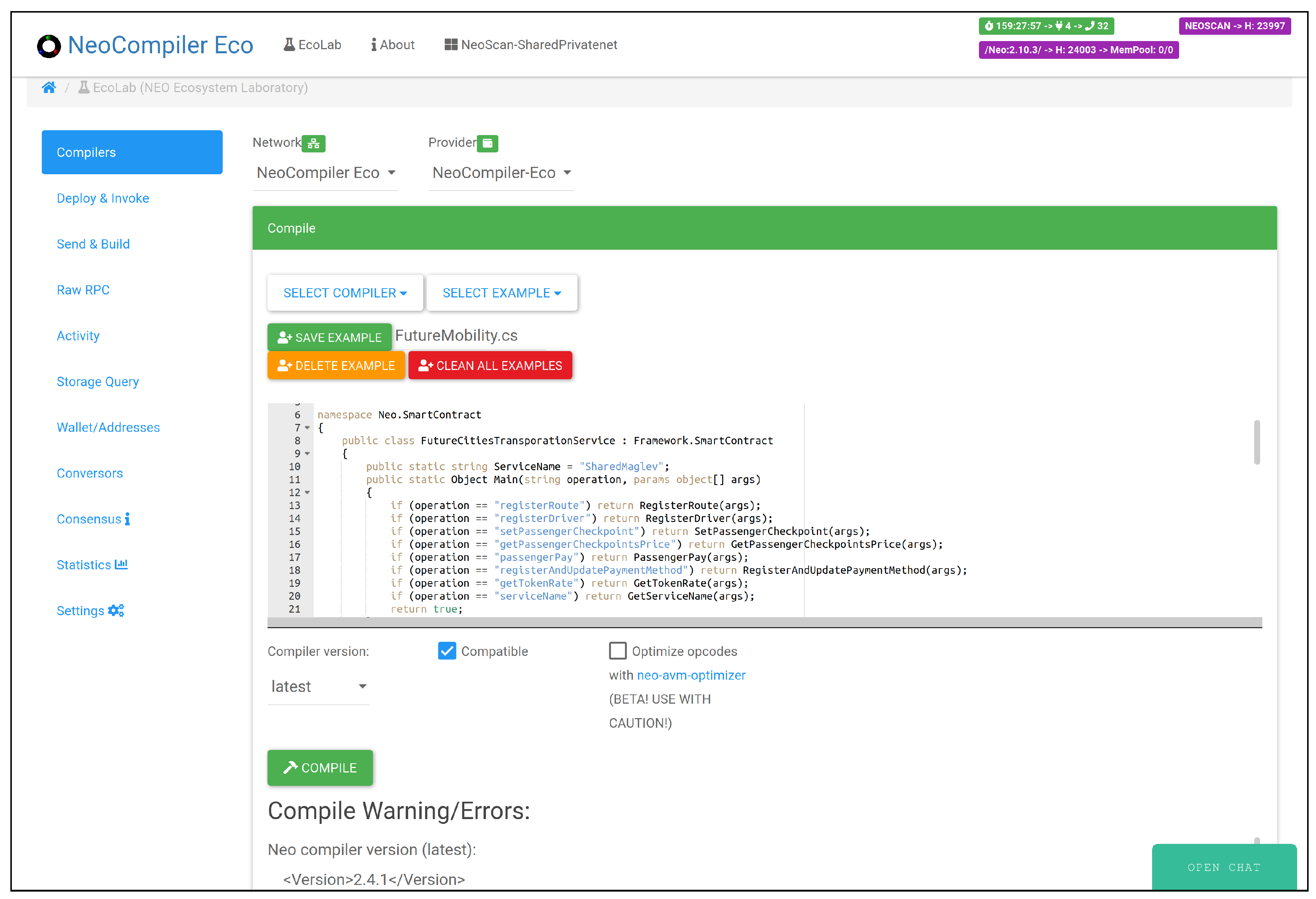

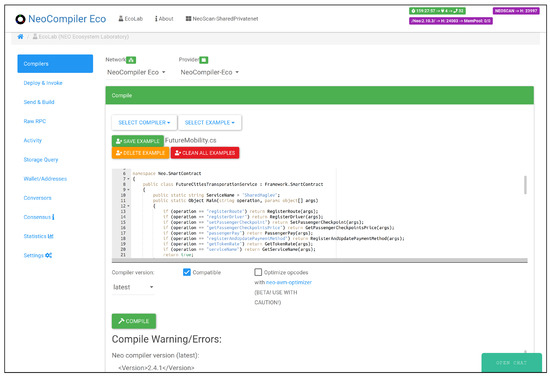

Ultimately, an example of a brief note on a Smart Contract developed in C# can be seen in Figure 4. Basically, this contract, designed for a service called FutureCitiesTransportationService, could have the following functions (not limited to): registerDriver, registerPassenger, setPassengerCheckpoint, getPassengerCheckpointsPrice, passengerPay, registerAndUpdatePaymentMethod and getTokenRate. Function registerDriver could be able to register drivers of the service, while function registerPassenger could be public calling for all passengers that wish to use such service. When boarded onto the transportation, automatically, this system could call setPassengerCheckpoint for each bus stop the passenger has passed through. When leaving the service, automatically, the price would be shown to the passenger by calling the function getPassengerCheckpointsPrice, which the passenger would sign and pay by calling passengerPay. The payment could be done by any token listed with registerAndUpdatePaymentMethod and obtained with current rates of exchange calling function getTokenRate. It should be noticed that setPassengerCheckpoint could be anonymous in terms of which passenger is taking the route, in order to avoid leaks or privacy invasion. However, if the passenger did not pay its debt, that data could be decrypted in order to expose the pending amount to be payed.

Figure 4.

A draft of some functions that could be called for registering operations on the NEO Blockchain, designed with the assistance of https://neocompiler.io.

3.5.2. Removing the Trust Barrier

As aforementioned, blockchain inspired technologies have been emerging as a mechanism for promoting transparency and reducing costs through the distribution of responsibilities and resources to manage an informational network. The advance in the use of personal data to foster business strategies has been gaining attention for a couple of years [175] because of trade-offs between private profitability, social well-being and public awareness about individual life data. Although users’ motion data have been important to offer novel transportation options, the way we interact with this data and reach agreements still requires third parties. Turning the latter into a transparent layer is one of the main possibilities of DApps.

Besides the good practices governments have been proposing to handle these issues [175], the Blockchain technology has been seen as a good solution [176,177] for empowering citizens over their data control (self-sovereign identities) and promote reliable cities’ transportation systems. For instance, instead of each application collecting user’s personal data to manage their transport system, and acting individually to try to satisfy their clients’ motion around, the DApps can privately share individual motion data between several transportation systems in order to allow a better data management. This data sharing would be enabled only by specific users’ digital signatures over the piece of information they agree to share.

Considering these points, Blockchain appears as a new trend in the area of urban management, balancing data control and flow of money between parties (as will be detailed in Section 3.5.4). Thus, its use opens a completely new mindset where fully-distributed solutions are feasible. In addition to strengthening the use of more competitive tools, the population should be conscious about the possibilities of interacting with intelligent cities’ systems, as well as being aware of the data that is being measured and stored. Blockchain based technologies are a disruptive manner of balancing efficiency and trust regarding the use of data measured inside cities’. In addition, such systems have been advocated as more robust and resilient, as well as censorship resistance, which are desirable components for public transportation systems.

These fully distributed systems are able to interact with cryptocurrencies and the services they provide, promoting the emergence of a true IoV. For example, social car pulling could be done by means of automatic smart contracts, which would surely increase transparency and reduce administrative costs. These platforms that contain personalized virtual machine environment comes as an alternative for providing infrastructure to several new startup projects [178].

3.5.3. The Potential of 5G and V2X

While Blockchain contracts may operate offchain [179] and then be published on a public or private chain, the need for a more robust and efficient internet connection is evident [180]. In this sense, we highlight how the concept of Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) intersects with 5G evolution as a core component of cities’ communication [181,182].

By decentralizing transportation, more sophisticated communication paradigms may emerge, in which information can be accessed throughout a swarm of devices. Aligned with Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) [183], this mesh of a vehicular network can surely contribute with the core concepts of Blockchain consensus mechanisms, in which an MAS of vehicles, drones and smartphones would interact with the network. An intersection of these concepts is the Cellular V2X protocol [184], which appears to be suitable for several real applications in the cities’ transportation scenario [185]. Besides the efficiency and robustness that such systems may offer, DSRC technology can be more cost-effective than the traditional concept of expanding cellular communication networks [186]. Blockchain technology enabled via V2X DSRC can provide to users a new level of experience in making business and interacting with the financial world. For instance, Jaguar Land Rover recently commented about a partnership with IOTA for cryptocurrency earning when driving their cars [187] via cars’ smart wallets. This kind of incentive is interesting and can also be applied on self-organized social systems, such as embedding on platforms such as Waze, Maps.me, among others. In this sense, these same kinds of incentives may appear in such self-organized systems focused on the relationship between users when navigating throughout the cities.

3.5.4. Applications for Carpooling and Ride-Sharing

Along with the advance of novel technologies, new interactive ways of transportation have emerged such as carpooling and ride-sharing, which changes the traditional format of getting around inside the cities [188]. A new range of users has been engaged in these new forms of transportation while new applications arose. With such technologies, we have the possibility of sharing destination, costs and personalizing our trip in a much easier way. Furthermore, it shows up as the first time in the modern society in which P2P online transportation [189] emerges in the concept of IoV .

On the users’ side, it gives them the possibility of choosing their preferences about routes and even car models [190], such as opting for a ride-sharing with an electric car, e-scooters or motorcycles and bikes. For example, a given person can even ride a vehicle in a given street street and left it in another random point or station. These decentralized transportation systems are beneficial due to the volume of cars on the runway, being useful in the peak hours, during parking, reducing congestion and, in a sustainable view, reducing pollution [191,192]. Summed up with the possibility of learning from the data [193], these decentralized methodologies gain a huge potential to provide profits to service providers.

Usually, this carpooling and ride-sharing are offered by dedicated online platforms, in mobile applications and websites [194]. In this sense, this type of transport can be seen as a flexible and tailored solution that solves a wide dimension of transport problems [191]. In connection with this line of reasoning, we can say that the evolution of these systems is related to DLT technologies and DApps. There is an open field of privacy concerns, transparency and digital payments that will cross its roots with such applications. In this sense, we believe that integration of such decentralized transportation system will soon have an intersection with cryptocurrencies and smart contracts. The flow of payments between users and those who offer the service should be more automatic, offering rules that are clear to both sides. In this sense, those who offer the service would not control identities and money anymore, they would be just a channel (a book of offers) in which services would flow a negotiation protocol with rules guided by smart contracts.

4. Final Remarks

4.1. Final Considerations

The academy and the industry have been directing their efforts in a race to improve urban environments, but this transition will have no meaning if the goals and desires of the citizens are not considered. In particular, the industry focuses on competitiveness and, for achieving better profits and a more wide public, the technologies and trends described in this paper can be seen as a must read manual. One of the key points of living in cities’ turbulent environments is obviously related to mobility, as highlighted in the survey of Barbosa et al. [195]. In this sense, society is facing the opportunity of guiding the evolution of one of the most immense sets of machines ever built, the urban cities. Evolving and building new urban centers adequately are extremely important for building efficiently designed systems that will be the pillars for future generations. Besides promoting the use of renewable resources, and their interaction with classic urban logistics problems, solutions that rely on digital technologies can boost a better quality of life.

In this paper, recent trends towards autonomous transportation systems for the future Digital and Smart Cities were discussed. The insertion of emerging transportation systems into the current cities requires a strategical, comprehensive, operational and technical analysis. In particular, state-of-the-art optimization methods should be considered and embedded into the best available high performance computers in order to process the huge amount of data currently available both for private and public interests. The potential of Smart Contracts designed with DLTs was particularly highlighted along this study, detailing how decentralized transportation systems could be profitable and more transparent for service providers and users. However, studies in the literature have been showing that new technologies still face challenges in terms of skeptcism. For instance, the distrust of V2G has been shown to be highly prevalent in a study in the Nordic region [196]. This is one of the main reasons that we believe that studies, such as the one conducted throughout this paper, have a great potential for triggering cities’ transformation.

This study recapitulates that, once considering the inclusion of novel technologies, it is quite relevant to determine the impacts it may promote. Besides that, it is important to have in mind that each context has a specificity and may respond to the introduction of technologies differently. In this sense, combining strategies that promote social development and also looking toward a more effective and efficient urban environment are essential. For this reason, the renewal of cities’ transportation should be assisted by devices able to perform multi-criteria analysis and solve complex problems, considering citizens’ perspectives.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Focusing on the use of CI techniques is promising for an efficient and sustainable advancement of cities. The potential of the use of these tools should be emphasized, which can be able to: reduce operational costs; improve various services offered in urban environments; promote fairer and more balanced systems; contrast long-term planning models with efficient solutions that process real-time data; and, in summary, increase the quality of life and human wellbeing. By considering state-of-the-art optimization tools, such as metaheuristic based algorithms [197,198,199,200], along with high-performance computing architectures, a sea of data measured by intelligent devices can be mined, processed, learned, predicted and integrated in the search of optimized solutions for our cities.

Studying, designing and developing these systems have a great potential to provide sustainable services, improve services quality and raise awareness about the different possibilities that new technologies are enabling. In this sense, the authors would like to reiterate that there is still a family of open problems that the new generation may work on. In addition, classical problems which were commonly handled as single objectives, and optimized based on a specific metric, may still have research potential. We believe that this potential is mostly due to how humans adjust their vision on their needs; thus, new tools have emerged and, in consequence, brought to society new possibilities to think about. The need for designing solutions that are more friendly and promote a sustainable urban environment are not only citizens’ wishes but also tools with the potential for reducing companies’ costs and enhancing their profits. The latter happens because when society wishes changes the economy model behind it is also transformed, proportioning a new path for being optimized in order to attend the needs of the modern transportation systems.

Finally, the implementation of platforms that promote the decentralization of trust in the context of cities’ transportation will surely change the way we are interacting with the emerging P2P transportation systems.

Author Contributions

The group of authors contain researchers with a variety of backgrounds, from applied computers scientists to specialists in business and social science. Some authors are closely connected with each other, which have been collaborating with brilliant scientists from Brazil, Spain, Israel and France, co-authors of this paper. Physicists were able to connect this study with state-of-the-art concepts of cutting-edge batteries while computer scientists gave the touch of computational intelligence and high-performance computing. The integration of transportation system is considered with contributions from control and automation engineers while integration with citizens and possibilities of blockchain technologies are handled by those engaged in the field of social sciences and also contributors of different open-source blockchain projects. We believe that our team represents the current possibilities that a globalized world and the future internet can offer, in which science is worldwide and can share visions from different cultures and ideologies, giving light to society while instigating readers with peculiar questions and answers. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Thays A. Oliveira, Vitor N. Coelho and Igor M. Coelho would like to thank the partnership with NeoResearch community and support of Neo Foundation. Miquel Oliver was supported by the Spanish Government under projects TEC2016-79510-P (Proyectos Excelencia 2016) and 2017-SGR-1739. Vitor N. Coelho was funded by FAPERJ grant number E-26/202.868/2016. Luiz S. Ochi, Fábio Protti and Igor M. Coelho were partially supported by the CNPq and FAPERJ. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks the different supports and efforts that were done among in order to make this research a reality. In addition, thanks all past generation for providing us with the necessary background for summarizing the information open-source shared within this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI | Computational Intelligence |

| BFT | Byzantine Fault Tolerance |

| DApps | Decentralized Applications |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technologies |

| DSRC | Dedicated Short Range Communications |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoV | Internet of Value |

| MAS | Multi Agent Systems |

| MCCP | Minimum Coloring Cut Problem |

| P2P | Peer-to-peer |

| SC | Smart Cities |

| SMES | Superconductive Magnetic Energy Storage |

| SQUID | Superconducting Quantum Interference Device |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| VRP | Vehicle Routing Problems |

References

- Shetty, V. A tale of smart cities. Commun. Int. 1997, 24, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvapali, D.; Ramchurn, D.H.; Jennings, N.R. Trust in multi-agent systems. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2004, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Benenson, I. Multi-agent simulations of residential dynamics in the city. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 1998, 22, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Pallot, M.; Trousse, B.; Nilsson, M.; Oliveira, A. Smart cities and the future internet: Towards cooperation frameworks for open innovation. In The Future Internet Assembly; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Song, H.; Jara, A.J.; Bie, R. Internet of things and big data analytics for smart and connected communities. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.L.; Lenstra, J.K.; Kan, A.R.; Shmoys, D.B. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Guided Tour of Combinatorial Optimization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Colorni, A.; Dorigo, M.; Maffioli, F.; Maniezzo, V.; Righini, G.; Trubian, M. Heuristics from nature for hard combinatorial problems. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 1996, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E. Multi-criteria decision-making methods. In Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods: A Comparative Study; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego, H.; Moses, M.E. Cities as organisms: Allometric scaling of urban road networks. J. Trans. Land Use 2008, 1, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowke, R.; Prasad, D.K. Sustainable development, cities and local government: Dilemmas and definitions. Aust. Plan. 1996, 33, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseland, M. Toward Sustainable Communities: Solutions for Citizens and Their Governments, 4th ed.; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S. Green cities, growing cities, just cities?: Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, K.Z. Blockchain-based sharing services: What blockchain technology can contribute to smart cities. Financ. Innov. 2016, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, F.R.; Samper-Zapater, J.J.; Martinez-Dura, J.J.; Cirilo-Gimeno, R.V.; Plume, J.M. Smart Mobility Trends: Open Data and Other Tools. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2018, 10, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Cooper, D.; David, B. A literature survey on smart cities. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuhadar, L.; Thrasher, E.; Marklin, S.; de Pablos, P.O. The next wave of innovation-Review of smart cities intelligent operation systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of Things for Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A. The Internet of Money. Available online: https://www.bortzmeyer.org/internet-of-money.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Lynch, D.C.; Lundquist, L. Digital Money: The New Era of Internet Commerce; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buterin, V. On public and private blockchains. Ether. Blog, 6 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Derrible, S.; Kennedy, C. Applications of Graph Theory and Network Science to Transit Network Design. Transp. Rev. 2011, 31, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollio, V. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Quercia, D.; Schifanella, R.; Aiello, L.M.; McLean, K. Smelly maps: The digital life of urban smellscapes. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.06851. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, J.; Smithies, N. Accounting for the needs of blind and visually impaired people in public realm design. J. Urban Des. 2012, 17, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.C.; Pinheiro, R.G.; Protti, F.; Ochi, L.S. A hybrid iterated local search and variable neighborhood descent heuristic applied to the cell formation problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 8947–8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, L.; Ochi, L.S.; Protti, F.; Subramanian, A.; Martins, I.C.; Pinheiro, R.G.S. Efficient algorithms for cluster editing. J. Comb. Optim. 2016, 31, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, O.; Nouri, N. Reducing Energy Consumption in Smart Cities: A Scatter Search Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Denver, CO, USA, 20–24 July 2016; pp. 1459–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo, F.; Schmidt, F. Optimal Paths in Real Multimodal Transportation Networks: An Appraisal Using GIS Data from New Zealand and Europe. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Felipe_Lillo4/publication/268400265_Optimal_Paths_in_Real_Multimodal_Transportation_Networks_An_Appraisal_Using_GIS_Data_from_New_Zealand_and_Europe/links/5696489c08ae1c4279038b1d.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2020).

- Silva, J.; Rampazzo, P.B.; Yamakami, A. Urban Mobility in Multi-Modal Networks Using Multi-Objective Algorithms. In Smart and Digital Cities; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Völkel, T.; Weber, G. RouteCheckr: Personalized multicriteria routing for mobility impaired pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 10th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–15 October 2008; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, B.L.; Assad, A.A.; Levy, L.; Gheysens, F. The fleet size and mix vehicle routing problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 1984, 11, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, I. Traveling Salesman-Type Combinational Problems and Their Relation to the Logistics of Blood Banking. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Koochaksaraei, H.R.; Enayatifar, R.; Guimarães, F.G. A New Visualization Tool in Many-Objective Optimization Problems. In Hybrid Artificial Intelligent Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Koochaksaraei, R.H.; Meneghini, I.R.; Coelho, V.N.; Guimaraes, F.G. A new visualization method in many-objective optimization with chord diagram and angular mapping. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 138, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotoli, M.; Zgaya, H.; Russo, C.; Hammadi, S. A Multi-Agent Advanced Traveler Information System for Optimal Trip Planning in a Co-Modal Framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, PP, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotoli, M.; Epicoco, N.; Falagario, M. A technique for efficient multimodal transport planning with conflicting objectives under uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2016 European Control Conference (ECC), Aalborg, Denmark, 29 June–1 July 2016; pp. 2441–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, C.; Amponsah, O.; Oduro, C. A system view of smart mobility and its implications for Ghanaian cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliaskopoulos, A.; Wardell, W. An intermodal optimum path algorithm for multimodal networks with dynamic arc travel times and switching delays. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 125, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbihi, A.; Eglese, R.W. Combinatorial optimization and Green Logistics. 4OR 2007, 5, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.; Bloemhof, J.; Mallidis, I. Operations Research for green logistics—An overview of aspects, issues, contributions and challenges. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; He, X. Multiple Depots Incomplete Open Vehicle Routing Problem Based on Carbon Tax. In Bio-Inspired Computing—Theories and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tao, F.; Shi, Y.; Wen, H. Optimization of Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows for Cold Chain Logistics Based on Carbon Tax. Sustainability 2017, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B.; Faulin, J.; Pérez-Bernabeu, E. A multicriteria analysis for the green VRP: A case discussion for the distribution problem of a Spanish retailer. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 22, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, S.; Arcelus, F.; Faulin, J. Green logistics at Eroski: A case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, H.; Zhijing, G.; Peng, Y.; Junqing, S. Vehicle routing problem with simultaneous pickups and deliveries and time windows considering fuel consumption and carbon emissions. In Proceedings of the 2016 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Yinchuan, China, 28–30 May 2016; pp. 3000–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoud, E.; Idrissi, A.E.B.E.; Alaoui, A.E. The green dynamic vehicle routing problem in sustainable transport. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Logistics Operations Management (GOL), Le Havre, France, 10–12 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S.; Shiu, E.; Steinberger-Wilckens, R. Changing the fate of Fuel Cell Vehicles: Can lessons be learnt from Tesla Motors? Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Baboli, A.; Rekik, Y. Multi-objective inventory routing problem: A stochastic model to consider profit, service level and green criteria. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 101, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.R.V.; Ochi, L.S. An efficient hybrid algorithm for the Traveling Car Renter Problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 64, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppstadt, C.; Koberstein, A.; Vigo, D. The Hybrid Electric Vehicle—Traveling Salesman Problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 253, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, B.; Fridshal, D.; Fridshal, R.; North, J.H. Design by natural selection. Synthese 1963, 15, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J. Exploration-exploitation trade-offs in metaheuristics: Survey and analysis. In Proceedings of the 33rd Chinese Control Conference, Nanjing, China, 28–30 July 2014; pp. 8633–8638. [Google Scholar]

- Woeginger, G.J. Exact algorithms for NP-hard problems: A survey. In Combinatorial Optimization—Eureka, You Shrink! Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R. The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal 2014, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemhauser, G.L.; Wolsey, L.A. Integer programming and combinatorial optimization. In Proceedings of the IPCO: International Conference on Integer Programming and Combinatorial Optimization, Houston, TX, USA, 22–24 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, V.N.; Coelho, I.M.; Souza, M.J.F.; Oliveira, T.A.; Cota, L.P.; Haddad, M.N.; Mladenovic, N.; Silva, R.C.P.; Guimaraes, F.G. Hybrid Self-Adaptive Evolution Strategies Guided by Neighborhood Structures for Combinatorial Optimization Problems. Evol. Comput. 2016, 24, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.S.; Papadimitriou, C.H.; Yannakakis, M. How easy is local search? J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1988, 37, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C. Efficient local search on the GPU—Investigations on the vehicle routing problem. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2013, 73, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymon, J.; Dominik, Ż. Solving multi-criteria vehicle routing problem by parallel tabu search on GPU. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 18, 2529–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sguglio, A.; Arcuri, N.; Bruno, R. Integration of Social Science in Engineering Research for Smart Cities. The Italian Case of the RES NOVAE Project. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I CPS Europe), Palermo, Italy, 12–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Want, R. Remembering Mark Weiser: Chief Technologist, Xerox Parc. IEEE Pers. Commun. 2000, 7, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nigon, J.; Glize, E.; Dupas, D.; Crasnier, F.; Boes, J. Use cases of pervasive artificial intelligence for smart cities challenges. In Proceedings of the 2016 Intl IEEE Conferences on Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced and Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing and Communications, Cloud and Big Data Computing, Internet of People, and Smart World Congress (UIC/ATC/ScalCom/CBDCom/IoP/SmartWorld), Toulouse, France, 18–21 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, T.A.; Barbosa, A.C.; Ramalhinho, H.; Oliver, M. Citizens and Information and Communication Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.A.; Coelho, V.N.; Tavares, W.; Ramalhinho, H.; Oliver, M. Desafios operacionais e digitais para conectar cidadãos em cidades inteligentes. Available online: http://www.sbpo2017.iltc.br/pdf/170636.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2020).

- Oliveira, T.A.; Coelho, V.N.; Ramalhinho, H.; Oliver, M. Digital Cities and Emerging Technologies. In Smart and Digital Cities; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovnik, M.; Herold, D.; Fürst, E.; Kummer, S. Blockchain for and in Logistics: What to Adopt and Where to Start. Logistics 2018, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. Can blockchain strengthen the internet of things? IT Prof. 2017, 19, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrobaee, S.; Rajabzadeh, R.A.; Soh, L.K.; Asgarpoor, S. Multiagent study of smart grid customers with neighborhood electricity trading. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2014, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabet, G.; Essaaidi, M.; Talei, H.; Abid, M.; Khalil, N.; Madkour, M.; Benhaddou, D. Applications of Multi-Agent Systems in Smart Grids: A survey. In Proceedings of the Multimedia Computing and Systems (ICMCS), Marrakech, Morocco, 14–16 April 2014; pp. 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.; Mehrizi-Sani, A.; Etemadi, A.; Canizares, C.; Iravani, R.; Kazerani, M.; Hajimiragha, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O.; Saeedifard, M.; Palma-Behnke, R.; et al. Trends in Microgrid Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]