In Silico Studies and Biological Evaluation of Thiosemicarbazones as Cruzain-Targeting Trypanocidal Agents for Chagas Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. In Silico Studies

2.3. In Vitro Assays Against Cruzain

2.4. In Vitro Assays Against Trypanosoma Cruzi

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assays in Human Fibroblasts (HFF1)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Trypanocidal Activity and Cytotoxicity

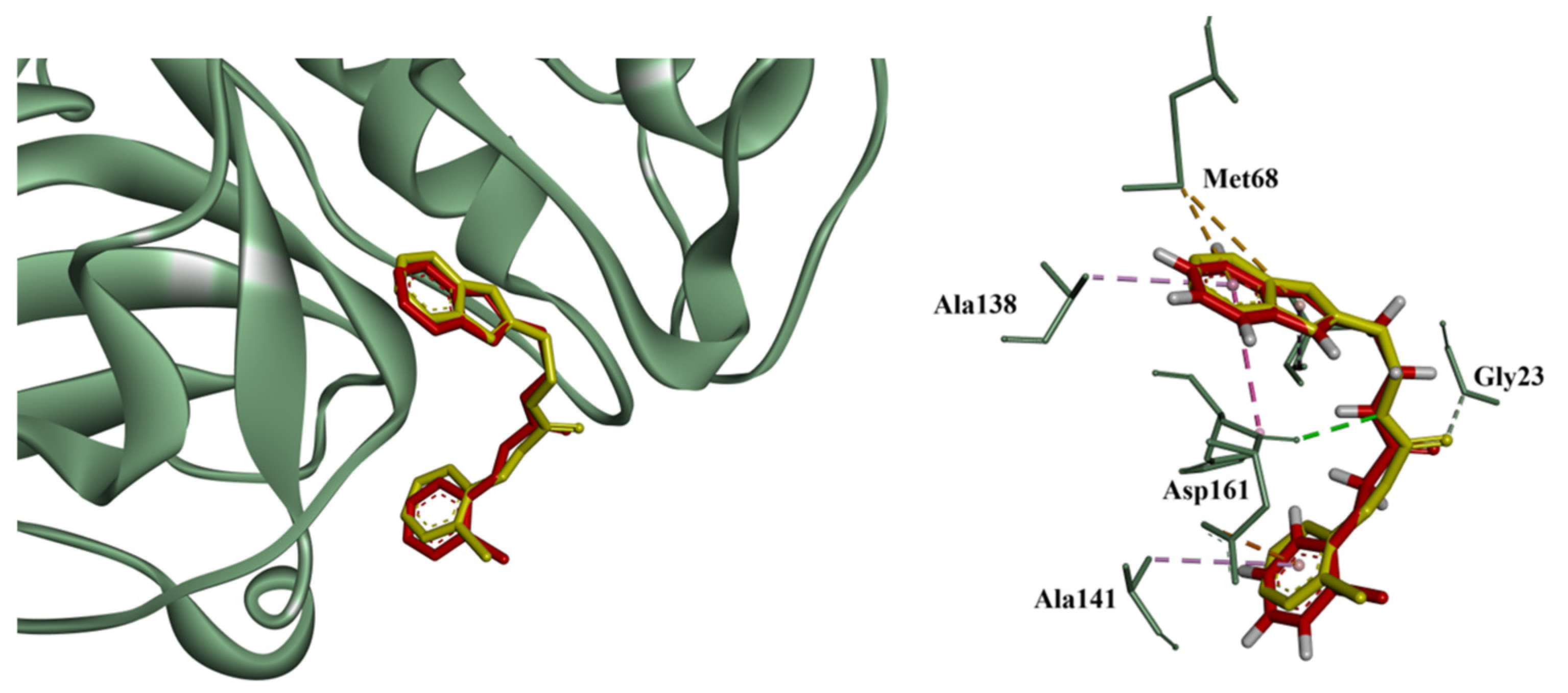

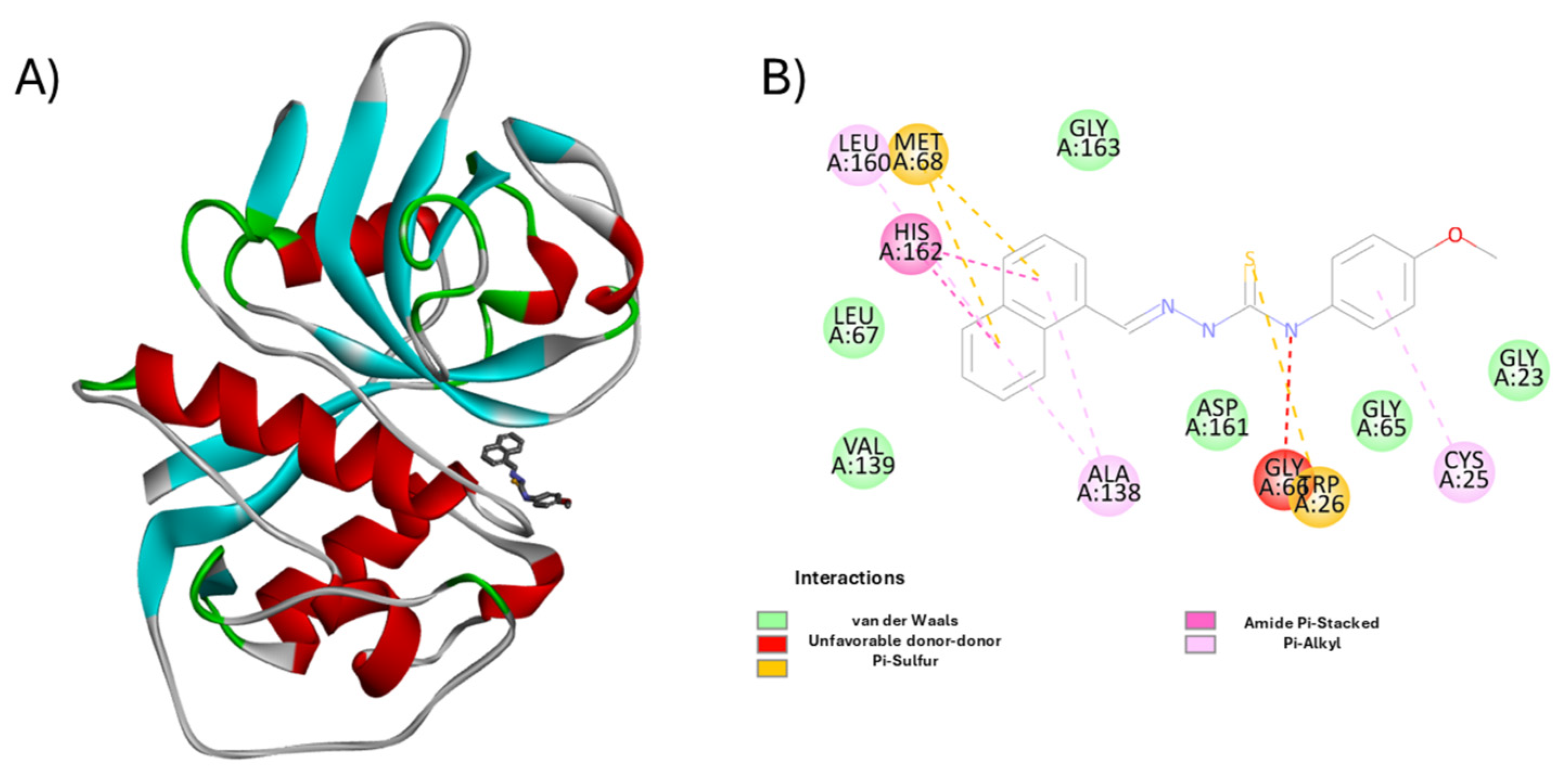

3.2. Molecular Docking and Enzymatic Inhibition

3.3. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Predictions

3.4. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Insights

- Maximize hydrophobic and π-interactions in the S2/S1′ subsites;

- Favor planar, conjugated systems for alignment with flat binding surfaces;

- Include electron-donating groups to support polar interactions without compromising solubility;

- Minimize steric hindrance near the hydrazone-thione region to avoid polar repulsion;

- Avoid strong electron-withdrawing or redox-a10/9/2025ctive groups such as nitro functionalities, as seen in H3 and H15, which were linked to elevated cytotoxicity.

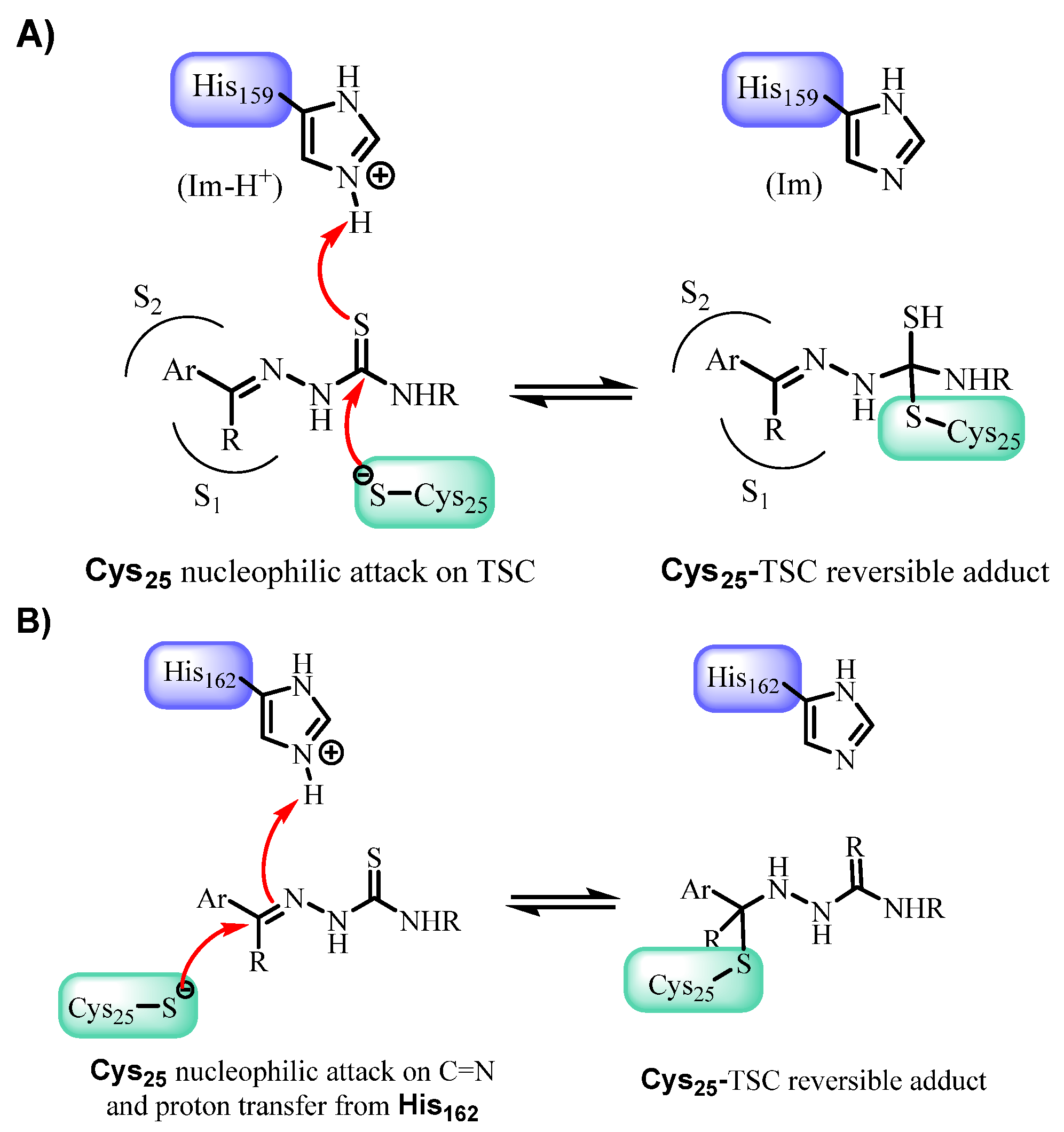

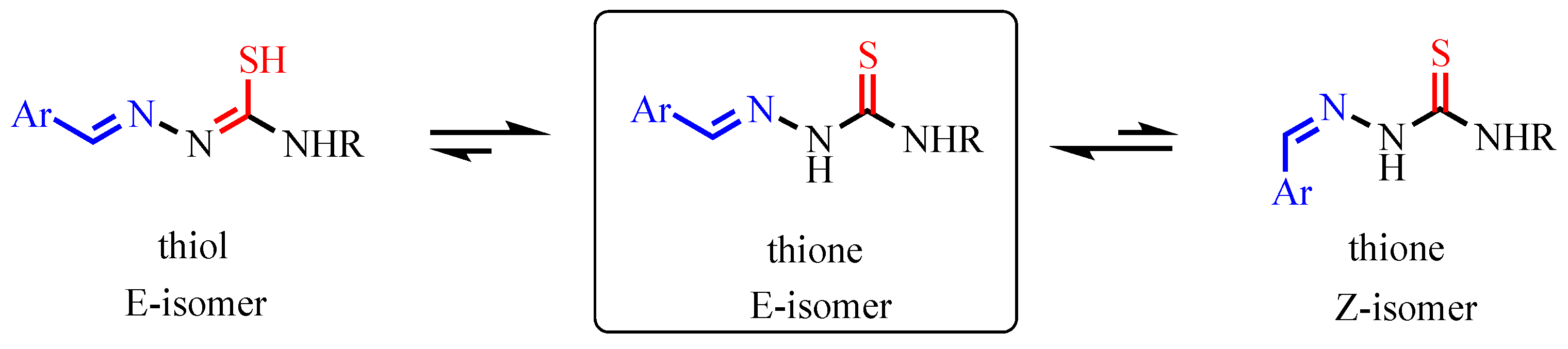

3.5. Mechanistic and Structural Insights into Cruzain Inhibition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Molina, J.A.; Molina, I. Chagas disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Chagas Disease (Also Know as American Trypanosomiasis. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis) (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Bern, C. Chagas’ Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Sevcsik, A.M.; Alves, F.; Diap, G.; Don, R.; Harhay, M.O.; Chang, S.; Pecoul, B. New, improved treatments for Chagas disease: From the R&D pipeline to the patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e484. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, M.E.; Eakin, A.E.; Engel, J.C.; McKerrow, J.H.; Craik, C.S.; Fletterick, R.J. The crystal structure of cruzain: A therapeutic target for Chagas’ disease. J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 247, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.C.; Leite, P.G.; Santos, L.H.; Pascutti, P.G.; Kolb, P.; Machado, F.S.; Ferreira, R.S. Structure-based discovery of novel cruzain inhibitors with distinct trypanocidal activity profiles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 257, 115498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gini, A.L.R.; Cunha, P.S.T.; João, E.E.; Chin, C.M.; dos Santos, J.L.; Serra, E.C.; Scarim, C.B. TrypPROTACs Unlocking New Therapeutic Strategies for Chagas Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, A.S.; Valli, M.; Ferreira, L.L.; Souza, J.M.; Krogh, R.; Meier, L.; Abreu, H.R.; Voltolini, B.G.; Llanes, L.C.; Nunes, R.J.; et al. Novel Trypanocidal Thiophen-Chalcone Cruzain Inhibitors: Structure- and Ligand-Based Studies. Future Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, E.A.; do Vale, I.H.; Sous, E.S.; Simplicio, S.S.; Gonsalves, A.A.; Araujo, C.R.M. Potential leishmanicidal of the thiosemicarbazones: A review. Results Chem. 2024, 9, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.C.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Lameira, J.; Ferreira, R.S. Experimental and Computational Study of Aryl-thiosemicarbazones Inhibiting Cruzain Reveals Reversible Inhibition and a Stepwise Mechanism. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.A.; da Silva Santos-Júnior, P.F.; Gomes, M.C.; Ferreira, L.A.S.; Padilha, E.K.A.; Teixeira, T.R.; Stanger, E.J.; Kaur, Y.; da Silva, E.B.; Costa, C.A.C.B. Nanomolar Activity of Coumarin-3-Thiosemicarbazones Targeting Trypanosoma Cruzi Cruzain and the T. Brucei Cathepsin L-like Protease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 283, 117109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linciano, P.; Moraes, C.B.; Alcantara, L.M.; Franco, C.H.; Pascoalino, B.; Freitas-Junior, L.H.; Macedo, S.; Santarem, N.; Cordeiro-da-Silva, A.; Gul, S.; et al. Aryl thiosemicarbazones for the treatment of trypanosomatidic infections. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, A.C.L.; Espindola, J.W.P.; de Oliveira Cardoso, M.V.; de Oliveira Filho, G.B. Privileged structures in the design of potential drug candidates for neglected diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 4323–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, E.M.G.; Di Iório, J.F.; da Silva, F.; Fialho, F.L.B.; Monteiro, M.M.; Beatriz, A.; Perdomo, R.T.; Barbosa, E.G.; Oses, J.P.; de Arruda, C.C.P.; et al. Flavonoid Derivatives as New Potent Inhibitors of Cysteine Proteases: An Important Step toward the Design of New Compounds for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.C.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Grinevicius, v.M.A.S.; Filho, D.W.; Zamoner, A.; Braga, A.L.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Ourique, F. IP-Se-06, a Selenylated Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine, Modulates Intracellular Redox State and Causes Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α and MAPK Signaling Inhibition, Promoting Antiproliferative Effect and Apoptosis in Glioblastoma Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3710449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.C.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Almeida, G.M.; Siminski, T.; Padua, C.; Filho, D.W.; Zamoner, A.; Braga, A.L.; Pedrosa, R.C.; et al. Apoptosis oxidative damage-mediated and antiproliferative effect of selenylated imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines on hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells and in vivo. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteselle, G.V.; Elias, W.C.; Bettanin, L.; Canto, R.F.S.; Salin, D.N.O.; Barbosa, F.A.R.; Saba, S.; Gallardo, H.; Ciancaleoni, G.; Domingo, J.B.; et al. Catalytic Antioxidant Activity of Bis-Aniline-Derived Diselenides as GPx Mimics. Molecules 2021, 26, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, M.; Botteselle, G.V.; Rafique, J.; Rocha, M.S.T.; Pena, J.M.; Braga, A.L. Solvent-free Fmoc protection of amines under microwave irradiation. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M.; Khalid, M.; Shahzadi, K.; Akhtar, T.; Saba, S.; Rafique, J.; Ali, S.; Irfan, M.; Alam, M.M.; Imran, M. Alkyl 2-(2-(arylidene) alkylhydrazinyl) thiazole-4-carboxylates: Synthesis, acetyl cholinesterase inhibition and docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1245, 131063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermiano, M.H.; das Neves, A.R.; da Silva, F.; Barros, M.S.A.; Vieira, C.B.; Stein, A.L.; Frizon, T.E.A.; Braga, A.L.; de Arruda, C.C.P.; Parisotto, E.B.; et al. Selenium-Containing (Hetero)Aryl Hybrids as Potential Antileishmanial Drug Candidates: In Vitro Screening against L. amazonensis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafique, J.; Farias, G.; Saba, S.; Zapp, E.; Bellettini, I.C.; Salla, C.A.M.; Bechtold, I.H.; Scheide, M.R.; Neto, J.S.S.; de Souza Junior, D.M. Selenylated-oxadiazoles as promising DNA intercalators: Synthesis, electronic structure, DNA interaction and cleavage. Dye. Pigm. 2020, 180, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizon, T.E.A.; Cararo, J.H.; Saba, S.; Dal-Pont, G.C.; Michels, M.; Braga, H.C.; Pimentel, T.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Valvassori, S.S.; Rafique, J. Synthesis of Novel Selenocyanates and Evaluation of Their Effect in Cultured Mouse Neurons Submitted to Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5417024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene, L.; de Souza, A.C.; Pacheco, L.A.; Mengatti, A.C.O.; Mori, M.; Mascarello, A.; Nunes, R.J.; Terenzi, H. Synthetic thiosemicarbazones as a new class of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase A inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 5742–5750. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwoski, G.; Kothiwale, S.; Meiler, J.; Lowe, E.W. Computational methods in drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 334–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.S.; Simeonov, A.; Jadhav, A.; Eidam, O.; Mott, B.T.; Keiser, M.J.; McKerrow, J.H.; Maloney, D.J.; Irwin, J.J.; Shoichet, B.K. Complementarity between a docking and a high-throughput screen in discovering new cruzain inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4891–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonk, M.L.; Cole, J.C.; Hartshorn, M.J.; Murray, C.W.; Taylor, R.D. Improved Protein–Ligand Docking Using GOLD. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2003, 52, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoee, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza-Chávez, R.M.; Oliveira Rezende Júnior, C.; de Souza, M.L.; Pauli, I.; Valli, M.; Gomes Ferreira, L.L.; Chelucci, R.C.; Michelan-Duarte, S.; Krogh, R.; Romualdo da Silva, F.B.; et al. Structure–Activity Relationships of Novel N-Imidazoylpiperazines with Potent Anti-Trypanosoma Cruzi Activity. Future Med. Chem. 2024, 16, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, G.; Moche, H.; Nieto, A.; Benoit, J.P.; Nesslany, F.; Lagarce, F. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of lipid nanocapsules. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 41, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes. Biovia Discovery Studio. 2023. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/support/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Du, X.; Guo, C.; Hansell, E.; Doyle, P.; Caffrey, C.; Holler, T.; McKerrow, J.; Cohen, F. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship study of potent trypanocidal thiosemicarbazone inhibitors of the trypanosomal cysteine protease cruzain. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2695–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, J.P.; Diniz, L.A.; Santos, V.C.; Vilchez Larrea, S.C.; Alonso, G.D.; Ferreira, R.S.; Dehaen, W.; Quevedo, M.A. Structure-Aided Computational Design of Triazole-Based Targeted Covalent Inhibitors of Cruzipain. Molecules 2024, 29, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinki, G.; Martini, M.F.; Moglioni, A.G. Thirty Years in the Design and Development of Cruzain Inhibitors. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2024, 35, e-20240115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinski, G.; Salas-Sarduy, E.; Vega, D.; Fabian, L.; Martini, M.F.; Moglioni, A.G. Thiosemicarbazone derivatives: Evaluation as cruzipain inhibitors and molecular modeling study of complexes with cruzain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 61, 116708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Cruzain IC50 (µM) | T. cruzi CC50 (μM) ± SD | HFF-1 CC50 ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.720 ± 0.015 | 09.80 ± 0.05 | >64 |

| H2 | 0.673 ± 0.065 | 10.15 ± 0.15 | >64 |

| H3 | 0.654 ± 0.085 | 04.23 ± 0.23 | 45.71 ± 1.03 |

| H4 | 0.678 ± 0.026 | 08.60 ± 0.25 | >64 |

| H5 | 0.675 ± 0.010 | 12.05 ± 0.85 | >64 |

| H6 | 0.640 ± 0.028 | 07.65 ± 0.35 | >64 |

| H7 | 0.306 ± 0.009 | 01.96 ± 0.05 | >64 |

| H8 | 0.655 ± 0.015 | 08.15 ± 0.25 | >64 |

| H9 | 0.685 ± 0.045 | 10.15 ± 0.45 | >64 |

| H10 | 0.512 ± 0.012 | 02.85 ± 0.13 | >64 |

| H11 | 0.412 ± 0.042 | 02.15 ± 0.26 | >64 |

| H12 | 0.699 ± 0.024 | 09.25 ± 0.35 | >64 |

| H13 | 0.636 ± 0.026 | 10.68 ± 0.15 | >64 |

| H14 | 0.605 ± 0.015 | 10.95 ± 0.54 | >64 |

| H15 | 0.630 ± 0.041 | 05.87 ± 0.05 | 51.26 ± 0.87 |

| H16 | 0.519 ± 0.023 | 2.95 ± 0.65 | >64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meier, L.; de Melo, M.F.C.V.; Abreu, H.R.; Oliveira, I.M.e.; Sens, L.; Doring, T.H.; Krogh, R.; Beatriz, A.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Saba, S.; et al. In Silico Studies and Biological Evaluation of Thiosemicarbazones as Cruzain-Targeting Trypanocidal Agents for Chagas Disease. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010065

Meier L, de Melo MFCV, Abreu HR, Oliveira IMe, Sens L, Doring TH, Krogh R, Beatriz A, Andricopulo AD, Saba S, et al. In Silico Studies and Biological Evaluation of Thiosemicarbazones as Cruzain-Targeting Trypanocidal Agents for Chagas Disease. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeier, Lidiane, Milena F. C. V. de Melo, Heitor R. Abreu, Isabella M. e Oliveira, Larissa Sens, Thiago H. Doring, Renata Krogh, Adilson Beatriz, Adriano D. Andricopulo, Sumbal Saba, and et al. 2026. "In Silico Studies and Biological Evaluation of Thiosemicarbazones as Cruzain-Targeting Trypanocidal Agents for Chagas Disease" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010065

APA StyleMeier, L., de Melo, M. F. C. V., Abreu, H. R., Oliveira, I. M. e., Sens, L., Doring, T. H., Krogh, R., Beatriz, A., Andricopulo, A. D., Saba, S., de Oliveira, A. S., & Rafique, J. (2026). In Silico Studies and Biological Evaluation of Thiosemicarbazones as Cruzain-Targeting Trypanocidal Agents for Chagas Disease. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010065