New Copper (II) Complexes Based on 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Ligands with Promising Antileishmanial Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

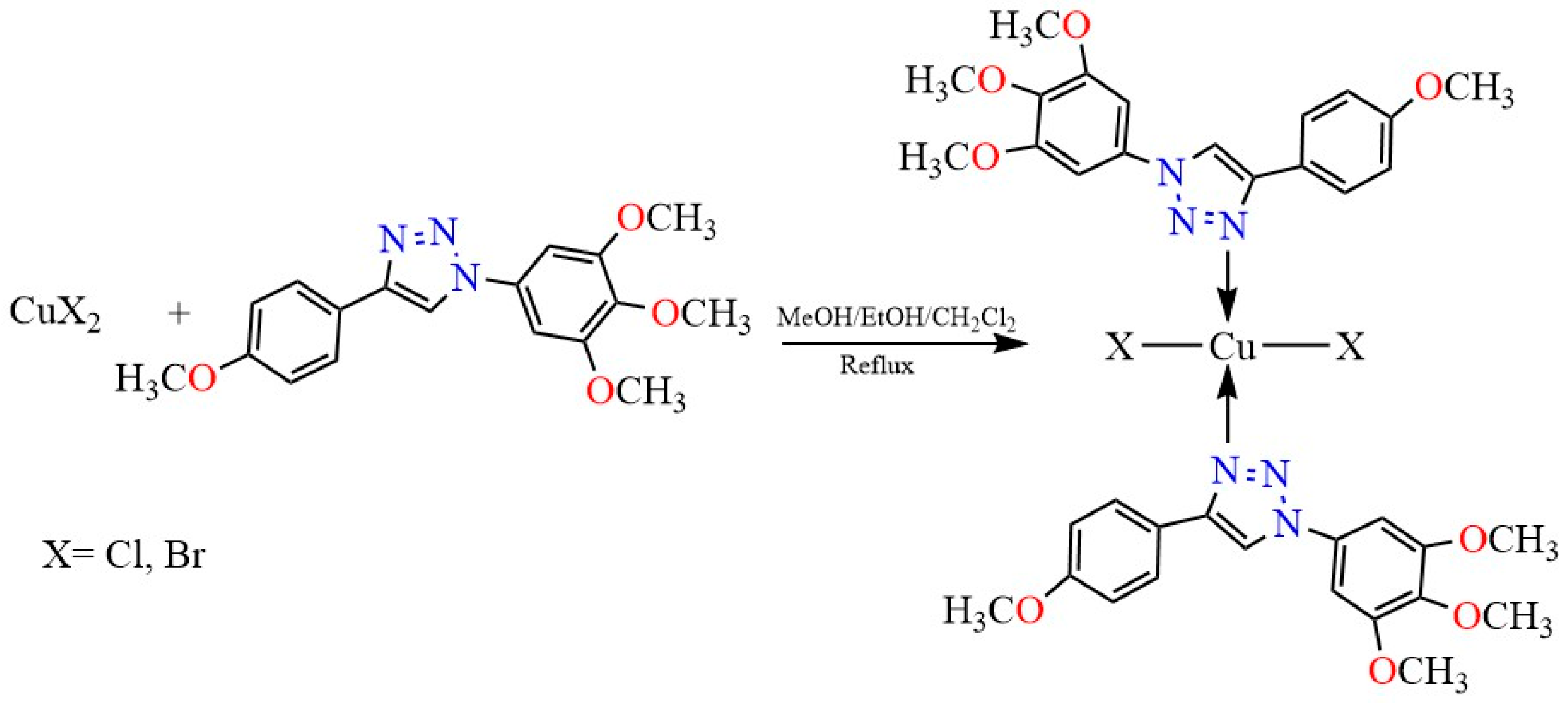

2.2. Synthesis of the Complexes

2.3. Biological Activity

2.3.1. Antileishmanial Assays

2.3.2. Animals and Parasites

2.3.3. Peritoneal Macrophages

2.3.4. Antipromastigote Assay

2.3.5. Treatment of Infected Macrophages

2.3.6. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

3. Results and Discussions

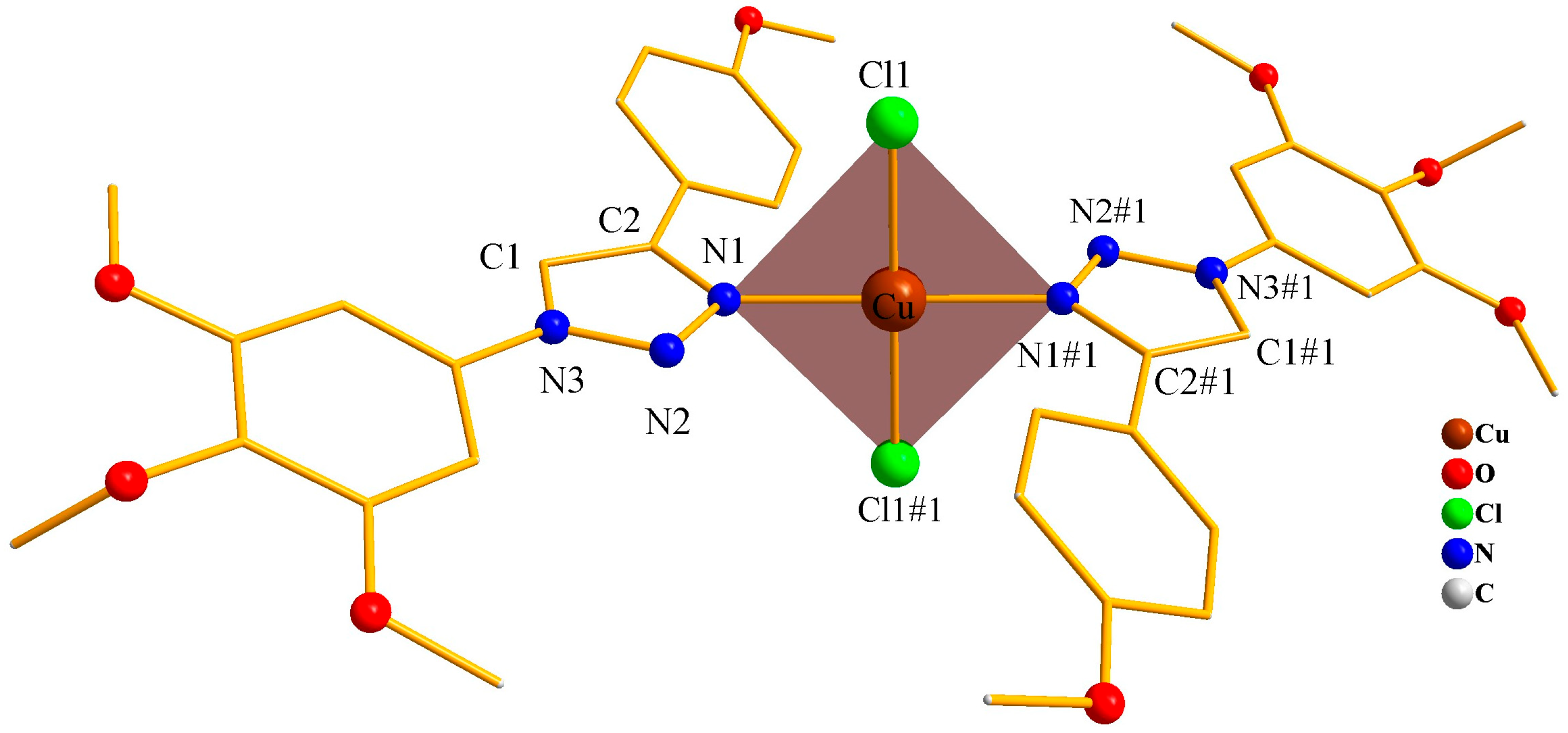

3.1. Crystalline Structure Description

3.2. Spectroscopic in the Mid-Infrared Region and Spectrometric Remarks

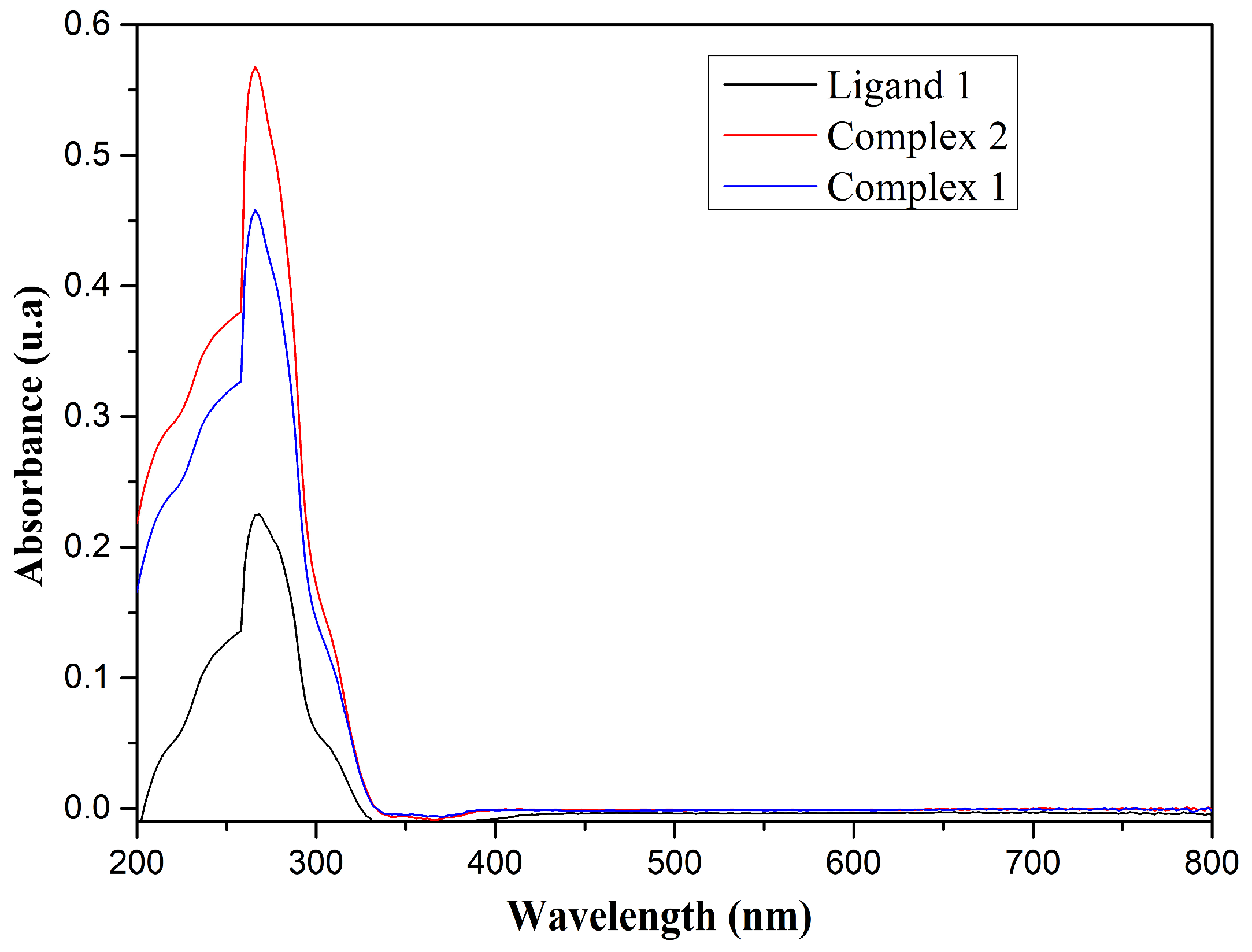

3.3. Spectroscopic Remarks in the Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Region

3.4. Antileishmanial Investigation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Leishmaniasis, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Leishmaniasis, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/gho-ntd-leishmaniasis (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Leishmaniose, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/topicos/leishmaniose (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Ponte-Sucre, A.; Gamarro, F.; Dujardin, J.C.; Barrett, M.P.; Lopez-Velez, R.; Garcia-Hernandez, R.; Pountain, A.W.; Mwenechanya, R.; Papadopoulou, B. Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; He, Z.; Xiao, J.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Ning, Q.; Li, Y. Progress in antileishmanial drugs: Mechanisms, challenges, and prospects. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0012735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.U. Parasitologia Contemporânea, 2nd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021; ISBN 978-85-277-3715-9. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, G.A.S.; Costa, D.L.; Costa, C.H.N.; De Almeida, R.P.; De Melo, E.V.; De Carvalho, S.F.G.; Rabello, A.; De Carvalho, A.L.; Sousa, A.D.Q.; Leite, R.D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Available Treatments for Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil: A Multicenter, Randomized, Open Label Trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafleur, A.; Daffis, S.; Mowbray, C.; Arana, B. Immunotherapeutic Strategies as Potential Treatment Options for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staśkiewicz, A.; Ledwoń, P.; Rovero, P.; Papini, A.M.; Latajka, R. Triazole-Modified Peptidomimetics: An Opportunity for Drug Discovery and Development. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 674705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdomir, G.; de los Angeles Fernandez, M.; Lagunes, I.; Padrón, J.I.; Martín, V.S.; Padrón, J.M.; Davyt, D. Oxa/Thiazole-Tetrahydropyran Triazole-Linked Hybrids with Selective Antiproliferative Activity against Human Tumour Cells. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 13784–13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J.; Khan, A.A.; Ali, Z.; Haider, R.; Shahar Yar, M. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Study and Design Strategies of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocyclic Moieties for Their Anticancer Activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaba, P.K. Triazolines. 14. 1,2,3-Triazolines and Triazoles. A New Class of Anticonvulsants. Drug Design and Structure-Activity Relationships. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-R.; Ren, Y.; Yin, X.-M.; Quan, Z.-S. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Anticonvulsant Activities of New 5-Substitued-[1,2,4]Triazolo [4,3-a]Quinoxalin-4(5H)-One Derivatives. LDDD 2018, 15, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-J.; Zhang, H.-J.; Quan, Z.-S. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Anticonvulsant Activities of 2,3-Dihydrophthalazine-1,4-Dione Derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2017, 26, 1935–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathi, V.; Sudhakar Reddy, G.; Padmaja, A.; Kondaiah, P. Ali-Shazia Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities of 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles, 1,3,4-Thiadiazoles and 1,2,4-Triazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, M.; Kim, H.W.; Gunic, E.; Jenket, C.; Boyle, U.; Koh, Y.; Korboukh, I.; Allan, M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; et al. Tri-Substituted Triazoles as Potent Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors of the HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4444–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boechat, N.; Ferreira, V.F.; Ferreira, S.B.; Ferreira, M.d.L.G.; de C. da Silva, F.; Bastos, M.M.; Costa, M.d.S.; Lourenço, M.C.S.; Pinto, A.C.; Krettli, A.U.; et al. Novel 1,2,3-Triazole Derivatives for Use against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) Strain. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5988–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskas, L.; Udrenaite, E.; Gaidelis, P.; Brukštus, A. Synthesis of 5-(2-,3- and 4-Methoxyphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Thiol Derivatives Exhibiting Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Il Farm. 2004, 59, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Peng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Li, J. Synthesis, in Vitro Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel Triazine-Triazole Derivatives as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, M.H.; Subhedar, D.D.; Arkile, M.; Khedkar, V.M.; Jadhav, N.; Sarkar, D.; Shingate, B.B. Synthesis and Bioactivity of Novel Triazole Incorporated Benzothiazinone Derivatives as Antitubercular and Antioxidant Agent. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Khan, S.I.; Rawat, D.S. Synthesis of 4-Aminoquinoline-1,2,3-Triazole and 4-Aminoquinoline-1,2,3-Triazole-1,3,5-Triazine Hybrids as Potential Antimalarial Agents: Synthesis of 4-Aminoquinoline-1,2,3-Triazole and 4-Aminoquinoline-1,2,3-Triazole-1,3,5-Triazine Hybrids. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2011, 78, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wen, C.; Wan, J.-P. Catalyst-Free Synthesis of 4-Acyl- NH -1,2,3-Triazoles by Water-Mediated Cycloaddition Reactions of Enaminones and Tosyl Azide. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 2348–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.R.; Gazolla, P.A.R.; da Silva, A.M.; Borsodi, M.P.G.; Bergmann, B.R.; Ferreira, R.S.; Vaz, B.G.; Vasconcelos, G.A.; Lima, W.P. Synthesis and Leishmanicidal Activity of Eugenol Derivatives Bearing 1,2,3-Triazole Functionalities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Cassamale, T.; Carvalho, D.; Bosquiroli, L.; Ojeda, M.; Ximenes, T.; Matos, M.; Kadri, M.; Baroni, A.; Arruda, C. Antileishmanial Activity and Structure-Activity Relationship of Triazolic Compounds Derived from the Neolignans Grandisin, Veraguensin, and Machilin G. Molecules 2016, 21, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassamale, T.B.; Costa, E.C.; Carvalho, D.B.; Cassemiro, N.S.; Tomazela, C.C.; Marques, M.C.S.; Ojeda, M.; Matos, M.F.C.; Albuquerque, S.; Arruda, C.C.P.; et al. Synthesis and Antitrypanosomastid Activity of 1,4-Diaryl-1,2,3-Triazole Analogues of Neolignans Veraguensin, Grandisin and Machilin G. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 27, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, D. Inorganic Chemistry, 6th ed.; W.H. Freeman and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, T.A.; Alam, A.; Zainab; Khan, M.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Tajuddin, A.M.; Ayaz, M.; Said, M.; Shah, S.A.A.; Khan, A.; et al. Copper(II) Complexes of 2-Hydroxy-1-Naphthaldehyde Schiff Bases: Synthesis, in Vitro Activity and Computational Studies. Future Med. Chem. 2025, 17, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touj, N.; Nasr, I.S.A.; Koko, W.S.; Khan, T.A.; Özdemir, I.; Yasar, S.; Mansour, L.; Alresheedi, F.; Hamdi, N. Anticancer, Antimicrobial and Antiparasitical Activities of Copper(I) Complexes Based on N -Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Ligands Bearing Aryl Substituents. J. Coord. Chem. 2020, 73, 2889–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola; Muhammad, N.; Khan, I.N.; Ali, Z.; Ibrahim, M.; Shujah, S.; Ali, S.; Ikram, M.; Rehman, S.; Khan, G.S.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Antioxidant, Antileishmanial, Anticancer, DNA and Theoretical SARS-CoV-2 Interaction Studies of Copper(II) Carboxylate Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1253, 132308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Falcao, S.; Mendez-Arriaga, J.M. Recent Advances in Metal Complexes Based on Biomimetic and Biocompatible Organic Ligands against Leishmaniasis Infections: State of the Art and Alternatives. Inorganics 2024, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, V.; Tisato, F.; Dolmella, A.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C.; Giorgetti, M.; Marzano, C.; Porchia, M. In Vitro and in Vivo Anticancer Activity of Copper(I) Complexes with Homoscorpionate Tridentate Tris(Pyrazolyl)Borate and Auxiliary Monodentate Phosphine Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4745–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.B.; Marín, C.; Ramírez-Macías, I.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Quirós, M.; Salas, J.M.; Sánchez-Moreno, M. Structural Consequences of the Introduction of 2,2′-Bipyrimidine as Auxiliary Ligand in Triazolopyrimidine-Based Transition Metal Complexes. In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity. Polyhedron 2012, 33, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Macias, I.; Marin, C.; Salas, J.M.; Caballero, A.; Rosales, M.J.; Villegas, N.; Rodriguez-Dieguez, A.; Barea, E.; Sanchez-Moreno, M. Biological Activity of Three Novel Complexes with the Ligand 5-Methyl-1,2,4-Triazolo[1,5-a]Pyrimidin-7(4H)-One against Leishmania Spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, E.M.G.; Da Silva, F.; Das Neves, A.R.; Bonfá, I.S.; Ferreira, A.M.T.; Menezes, A.C.G.; Da Silva, M.E.C.; Dos Santos, J.T.; Martines, M.A.U.; Perdomo, R.T.; et al. Investigation of the Potential Targets behind the Promising and Highly Selective Antileishmanial Action of Synthetic Flavonoid Derivatives. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 2048–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, E.M.G.; Di Iório, J.F.; Da Silva, F.; Fialho, F.L.B.; Monteiro, M.M.; Beatriz, A.; Perdomo, R.T.; Barbosa, E.G.; Oses, J.P.; De Arruda, C.C.P.; et al. Flavonoid Derivatives as New Potent Inhibitors of Cysteine Proteases: An Important Step toward the Design of New Compounds for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermiano, M.H.; Das Neves, A.R.; Da Silva, F.; Barros, M.S.A.; Vieira, C.B.; Stein, A.L.; Frizon, T.E.A.; Braga, A.L.; De Arruda, C.C.P.; Parisotto, E.B.; et al. Selenium-Containing (Hetero)Aryl Hybrids as Potential Antileishmanial Drug Candidates: In Vitro Screening against L. amazonensis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteselle, G.V.; Elias, W.C.; Bettanin, L.; Canto, R.F.S.; Salin, D.N.O.; Barbosa, F.A.R.; Saba, S.; Gallardo, H.; Ciancaleoni, G.; Domingos, J.B.; et al. Catalytic Antioxidant Activity of Bis-Aniline-Derived Diselenides as GPx Mimics. Molecules 2021, 26, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, D.C.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Grinevicius, V.M.A.S.; Filho, D.W.; Zamoner, A.; Braga, A.L.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Ourique, F. IP-Se-06, a Selenylated Imidazo[1,2-a]Pyridine, Modulates Intracellular Redox State and Causes Akt/mTOR/HIF-1 α and MAPK Signaling Inhibition, Promoting Antiproliferative Effect and Apoptosis in Glioblastoma Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3710449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, D.C.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Almeida, G.M.; Siminski, T.; Pádua, C.; Filho, D.W.; Zamoner, A.; Braga, A.L.; Pedrosa, R.C.; et al. Apoptosis Oxidative Damage-mediated and Antiproliferative Effect of Selenylated Imidazo[1,2-a]Pyridines on Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells and in Vivo. J Biochem Mol. Tox 2021, 35, e22663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Powell, D.R.; Houser, R.P. Structural Variation in Copper(I) Complexes with Pyridylmethylamide Ligands: Structural Analysis with a New Four-Coordinate Geometry Index, τ 4. Dalton Trans. 2007, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addison, A.W.; Rao, T.N.; Reedijk, J.; van Rijn, J.; Verschoor, G.C. Synthesis, Structure, and Spectroscopic Properties of Copper(II) Compounds Containing Nitrogen–Sulphur Donor Ligands; the Crystal and Molecular Structure of Aqua[1,7-Bis(N-Methylbenzimidazol-2′-Yl)-2,6-Dithiaheptane]Copper(II) Perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Espinosa, D.; Negrón-Silva, G.E.; Ángeles-Beltrán, D.; Álvarez-Hernández, A.; Suárez-Castillo, O.R.; Santillán, R. Copper(II) Complexes Supported by Click Generated Mixed NN, NO, and NS 1,2,3-Triazole Based Ligands and Their Catalytic Activity in Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 7069–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorda, K.; Keuleers, R.; Terzis, A.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Perlepes, S.P.; Plakatouras, J.C. Copper(II) Bromide/1-Methylbenzotriazole Chemistry. Polyhedron 1999, 18, 3067–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, A.; Varga, Z. Halogen Acceptors in Hydrogen Bonding. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, J.; Conradie, M.M.; Tawfiq, K.M.; Al-Jeboori, M.J.; Coles, S.J.; Wilson, C.; Potgieter, J.H. Novel Dichloro(Bis{2-[1-(4-Methylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-Triazol-4-Yl-κN3]Pyridine-κN})Metal(II) Coordination Compounds of Seven Transition Metals (Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn and Cd). Polyhedron 2018, 151, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktürk, T.; Hökelek, T.; Güp, R. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Hirshfeld Surface Analysis of Ethyl 4-(4-(2-Bromoethyl)-1H-1,2,3-Triazol-1-Yl)Benzoate. Crystallogr. Rep. 2021, 66, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhensdadia, K.A.; Lalavani, N.H.; Baluja, S.H. Synthesis of New Thieno[2,3-d]Pyrimidines Containing a 1,2,3-Triazole Ring and Their Therapeutic Response in NCI-60 Cell Line Panel. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 57, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.E. Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-12-814369-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz, J.R. (Ed.) Instrumentation for Fluorescence Spectroscopy. In Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 27–61. ISBN 978-0-387-31278-1. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Souza, F.; da Silva, V.D.; Silva, G.X.; Taniwaki, N.N.; de J. Hardoim, D.; Buarque, C.D.; Abreu-Silva, A.L.; Calabrese, K.d.S. 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Compounds Induce Ultrastructural Alterations in Leishmania Amazonensis Promastigote: An in Vitro Antileishmanial and in Silico Pharmacokinetic Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Farhoudi, R. Leishmaniasis in Humans: Drug or Vaccine Therapy? DDDT 2017, 12, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezar, R.D.; Silva, A.O.D.; Lopes, R.S.; Nakamura, C.V.; Rodrigues, J.H.S.; Lourenço, E.M.G.; Saba, S.; Beatriz, A.; Rafique, J.; Lima, D.P.D. Design, Synthesis and Identification of Novel Molecular Hybrids Based on Naphthoquinone Aromatic Hydrazides as Potential Trypanocide and Leishmanicidal Agents. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2024, 96, e20230375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.H.; Frézard, F.; Pereira, N.P.; Moura, A.S.; Ramos, L.M.Q.C.; Carvalho, G.B.; Rocha, M.O.C. American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis in Brazil: A Critical Review of the Current Therapeutic Approach with Systemic Meglumine Antimoniate and Short-term Possibilities for an Alternative Treatment. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Maffei, R.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Miguel, D.C.; Uliana, S.R.B.; Espósito, B.P. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of Antileishmanial Activity of Copper(II) with Fluorinated α-Hydroxycarboxylate Ligands. Biometals 2009, 22, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagmurlu, A.; Buğday, N.; Yaşar, Ş.; Boulebd, H.; Mansour, L.; Koko, W.S.; Hamdi, N.; Yaşar, S. Synthesis, DFT Calculations, and Investigation of Catalytic and Biological Activities of Back-bond functionalized re-NHC-Cu complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 38, e7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuno, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Duncan, K.; van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Kaneko, T.; Kita, K.; Mowbray, C.E.; Schmatz, D.; Warner, P.; Slingsby, B.T. Hit and Lead Criteria in Drug Discovery for Infectious Diseases of the Developing World. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Wavelength (cm−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Complex 1 | Complex 2 | |

| ν(C-H)ring | 3141 | 3132–3110 | 3128–3109 |

| ν(C-H)SP2 | 2989 | 3051–3004 | 2999 |

| ν(O-CH3)sp3 | 2941–2831 | 2941–2831 | 2933–2831 |

| ν(C=N) | 1562 | 1581 | 1579 |

| ν(C=C) | 1598 | 1614 | 1612 |

| ν(C-O-CH3) | 1230 | 1247 | 1249 |

| ν(N-N) | 1510 | 1514 | 1512 |

| Compounds | Peritoneal Macrophages CC50 a (µM) ± SD | Promastigotes of L. amazonensis IC50 b (µM) ± SD | SI c | Amastigotes of L. amazonensis IC50 d (µM) ± SD | SI e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex 1 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 28.0 ± 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.4± 0.0 | 9.7 |

| Complex 2 | 18.3 ± 1.6 | 16.3 ± 1.2 | 1.1 | 12.0 ± 1.0 | 1.5 |

| Ligand | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 17.7 ± 1.2 | 0.4 | 17.5 ± 1.2 | 0.4 |

| CuBr2 | 1.8 ± 3.0 | >50.0 ± 2.0 | >0.03 | 14.0 ±1.1 | 0.1 |

| CuCl2 2H2O | 13.6 ± 1.5 | >50.0 ± 2.0 | >0.3 | 20.8 ± 1.3 | 0.6 |

| AmB f | 13.8 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 5.5 |

| PENTA g | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 11.0 | 13.3 ± 0.3 | 1.6 |

| DXR h | 2.7 ± 6.8 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nascimento, J.P.C.; Faganello, N.L.; Freitas, K.F.; Pinto, L.M.C.; das Neves, A.R.; Carvalho, D.B.; Arruda, C.C.P.; Silva, S.M.; Almeida, R.C.F.; Júnior, A.M.; et al. New Copper (II) Complexes Based on 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Ligands with Promising Antileishmanial Activity. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010064

Nascimento JPC, Faganello NL, Freitas KF, Pinto LMC, das Neves AR, Carvalho DB, Arruda CCP, Silva SM, Almeida RCF, Júnior AM, et al. New Copper (II) Complexes Based on 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Ligands with Promising Antileishmanial Activity. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleNascimento, João P. C., Natali L. Faganello, Karolina F. Freitas, Leandro M. C. Pinto, Amarith R. das Neves, Diego B. Carvalho, Carla C. P. Arruda, Sidnei M. Silva, Rita C. F. Almeida, Amilcar M. Júnior, and et al. 2026. "New Copper (II) Complexes Based on 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Ligands with Promising Antileishmanial Activity" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010064

APA StyleNascimento, J. P. C., Faganello, N. L., Freitas, K. F., Pinto, L. M. C., das Neves, A. R., Carvalho, D. B., Arruda, C. C. P., Silva, S. M., Almeida, R. C. F., Júnior, A. M., Back, D. F., Pizzuti, L., Saba, S., Rafique, J., Baroni, A. C. M., & Casagrande, G. A. (2026). New Copper (II) Complexes Based on 1,4-Disubstituted-1,2,3-Triazole Ligands with Promising Antileishmanial Activity. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010064