Advanced Hybrid Polysaccharide—Lipid Nanocarriers for Bioactivity Improvement of Phytochemicals from Centella asiatica and Hypericum perforatum

Abstract

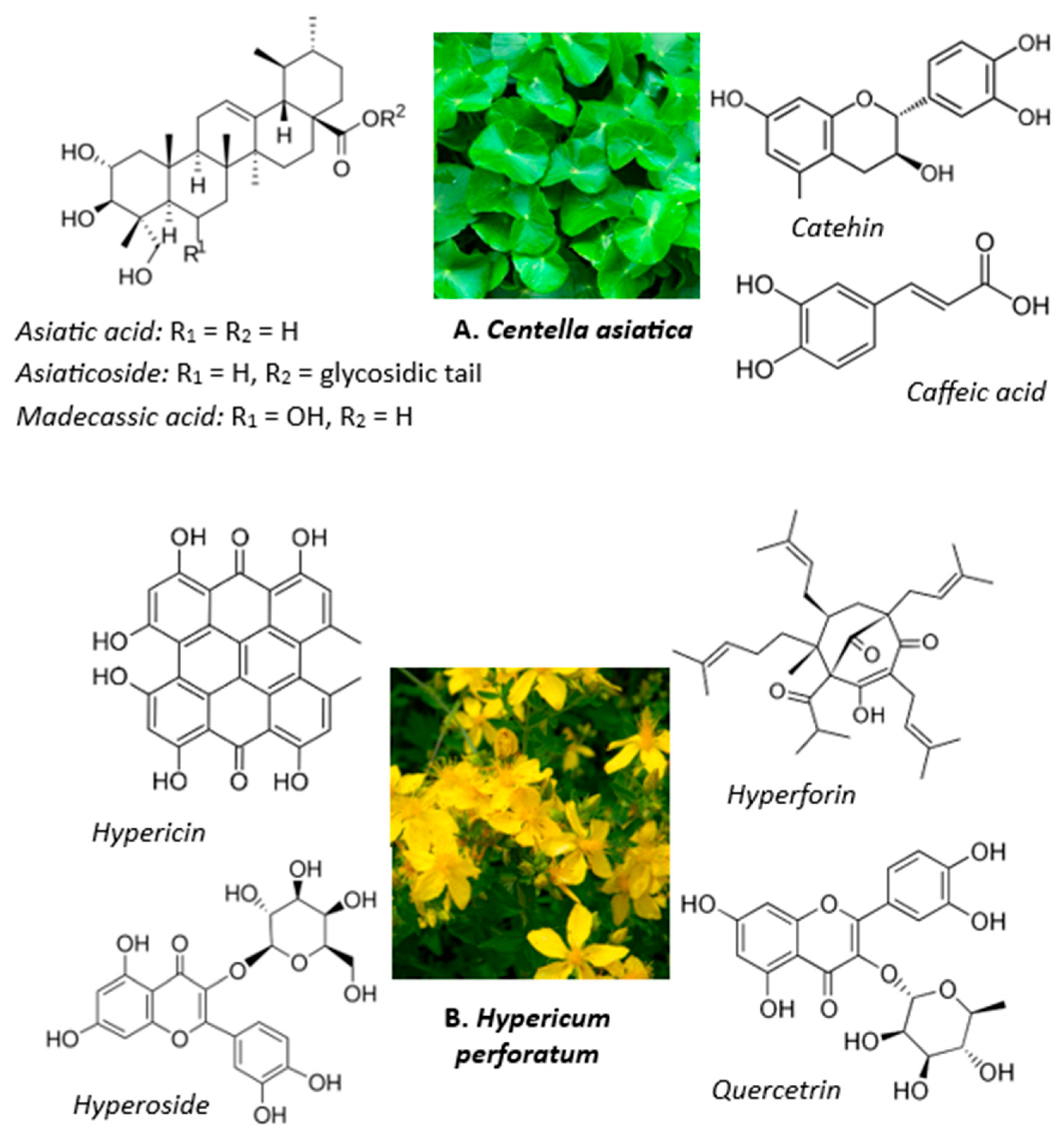

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Conventional and Hybrid HA-NLC-Entrapping Phytochemical Mixtures

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.3.1. Determination of the Size and Physical Stability of NLCs

2.3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Assay

2.3.3. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Characterization

2.3.4. Determination of Entrapment Efficiency

2.3.5. Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Action

2.3.6. In Vitro Release Study

2.3.7. Skin Fibroblast Cells

2.3.8. Cell Viability Assay

2.3.9. Morphological Evaluation by Fluorescence Microscopy

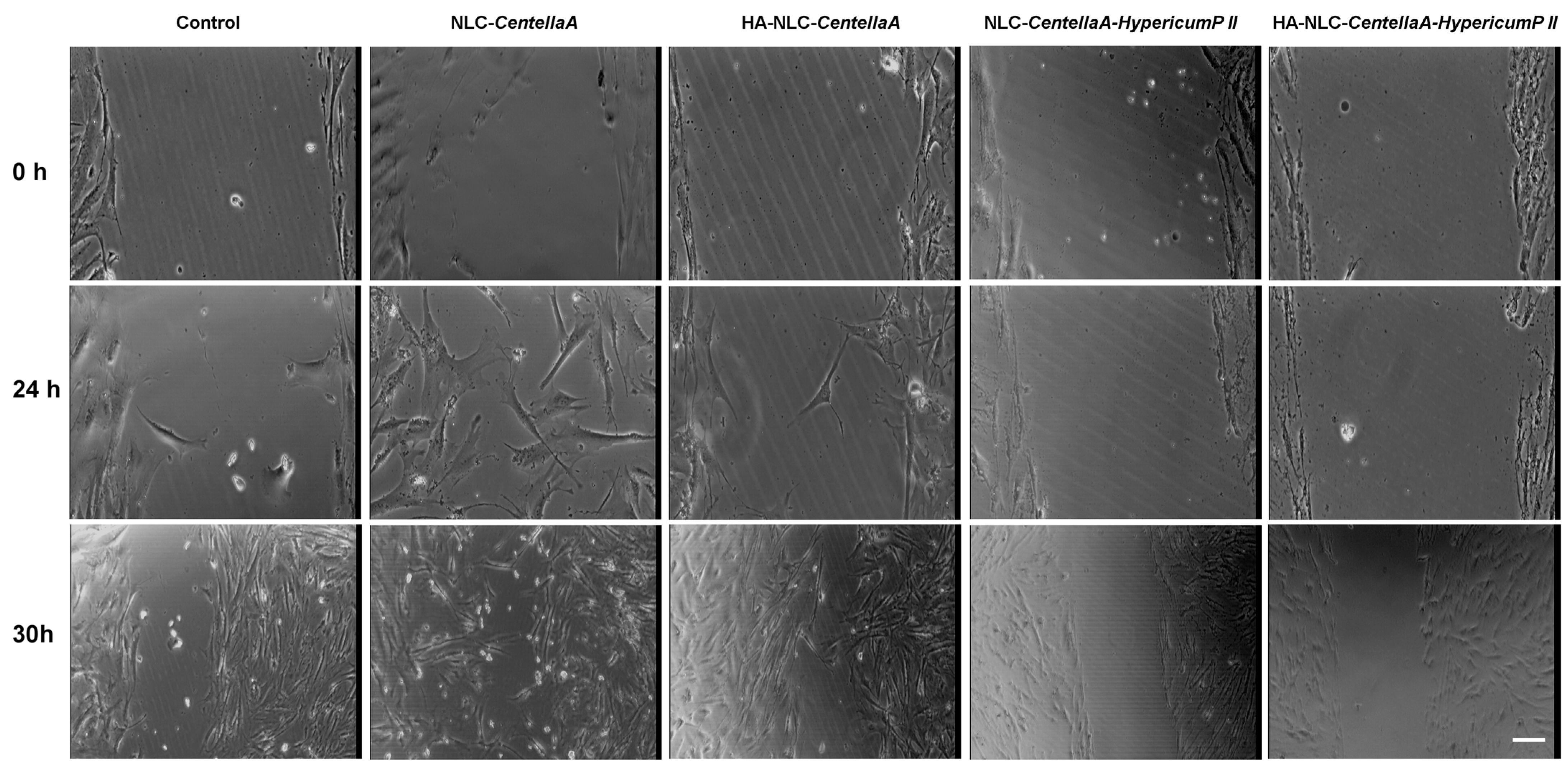

2.3.10. Wound Healing Assay

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Size, Stability, and Structural Characterization

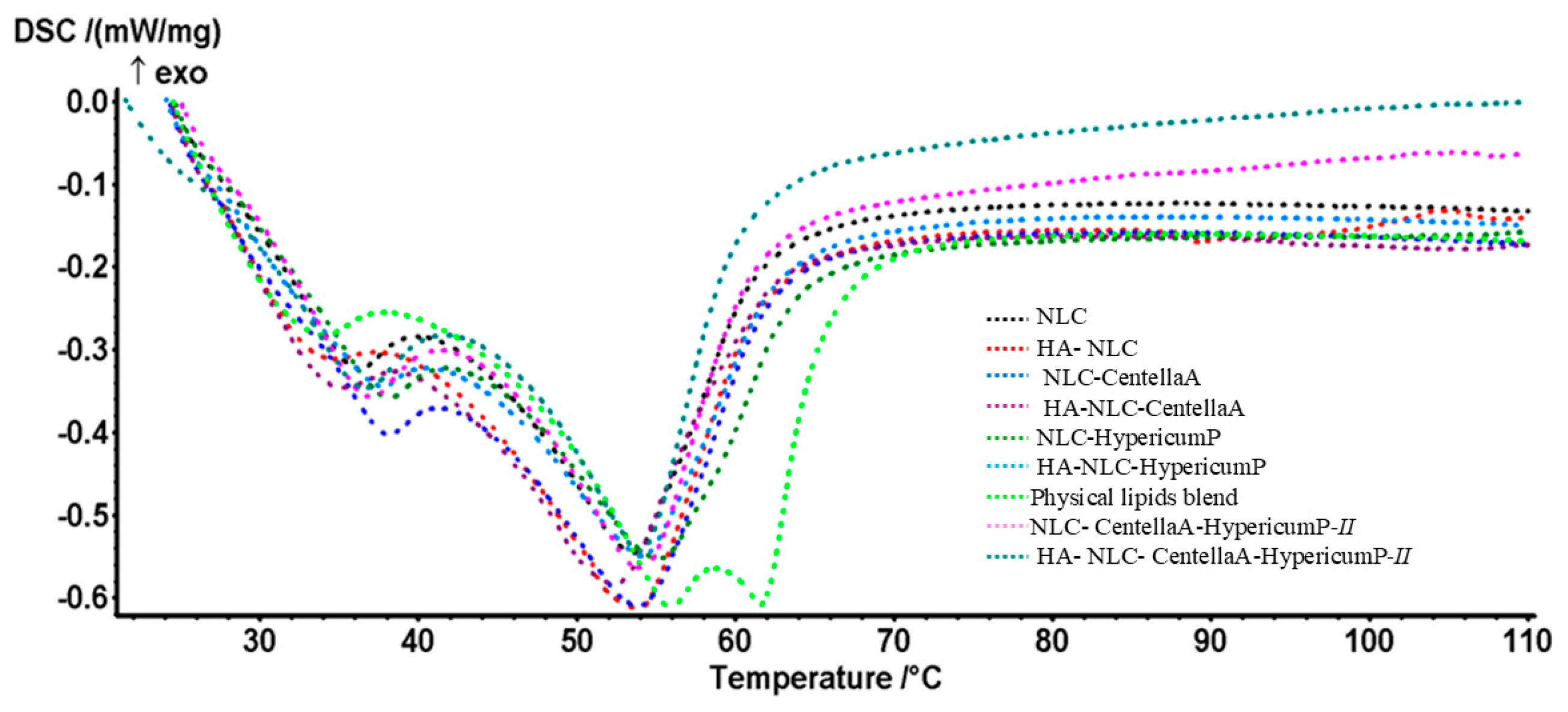

3.2. Thermal Behavior of the NLCs and HA-NLCs That Entrap Herbal Extracts

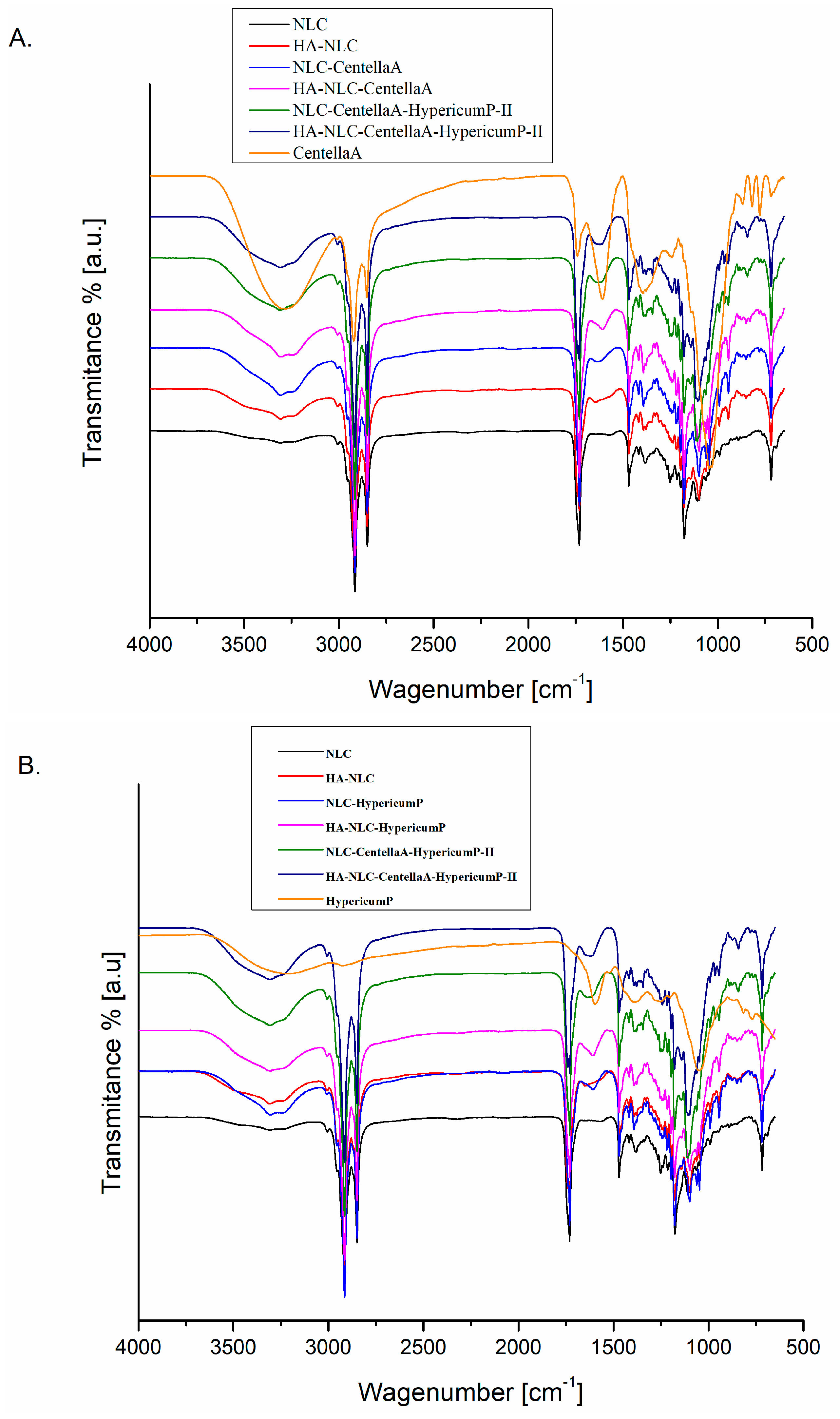

3.3. FTIR Characterization of NLCs and HA-NLCs That Entrap CentellaA Extract and/or HypericumP Extract

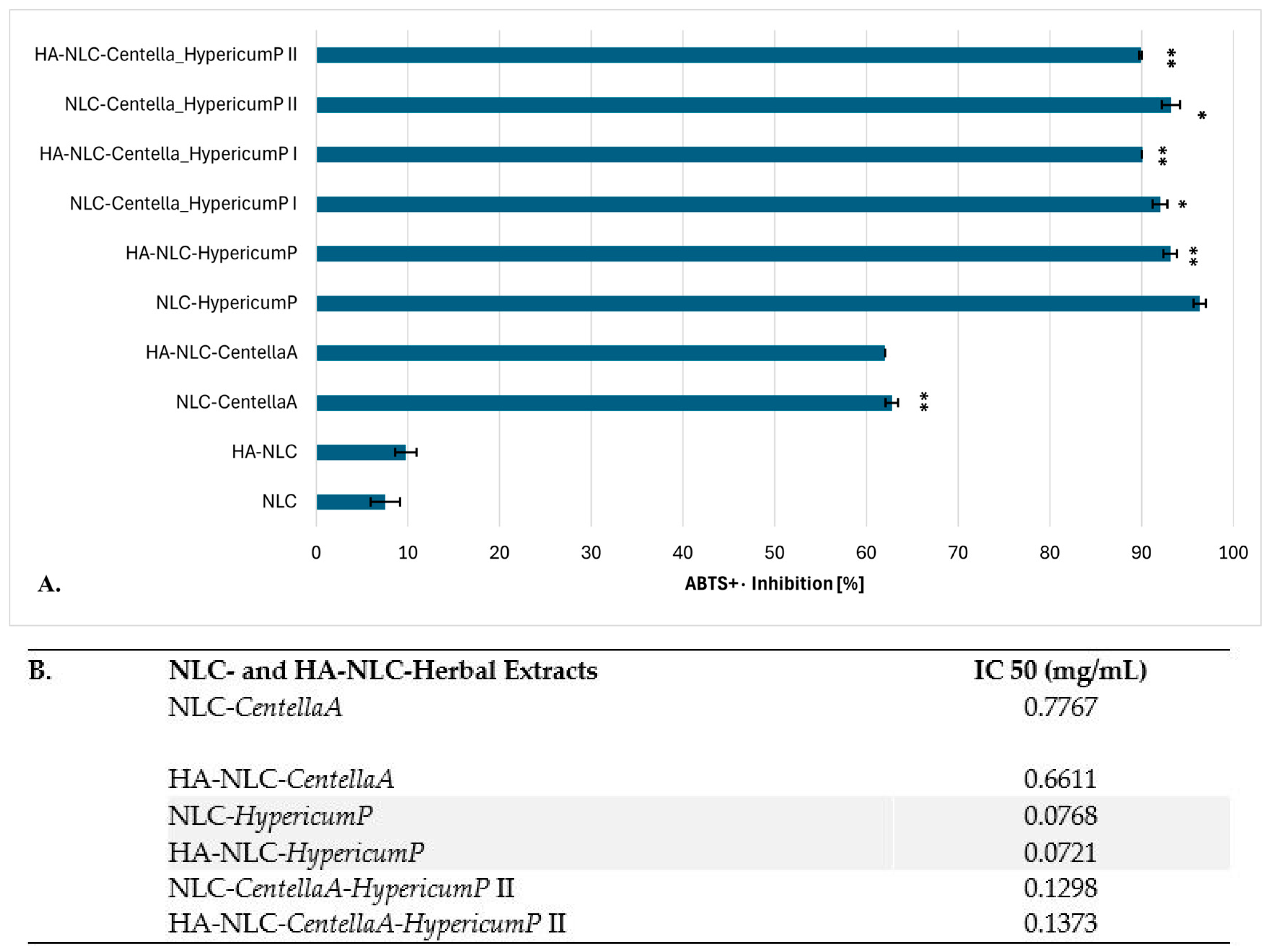

3.4. Ability of Conventional and HA-Coated NLCs to Manifest Antioxidant Activity

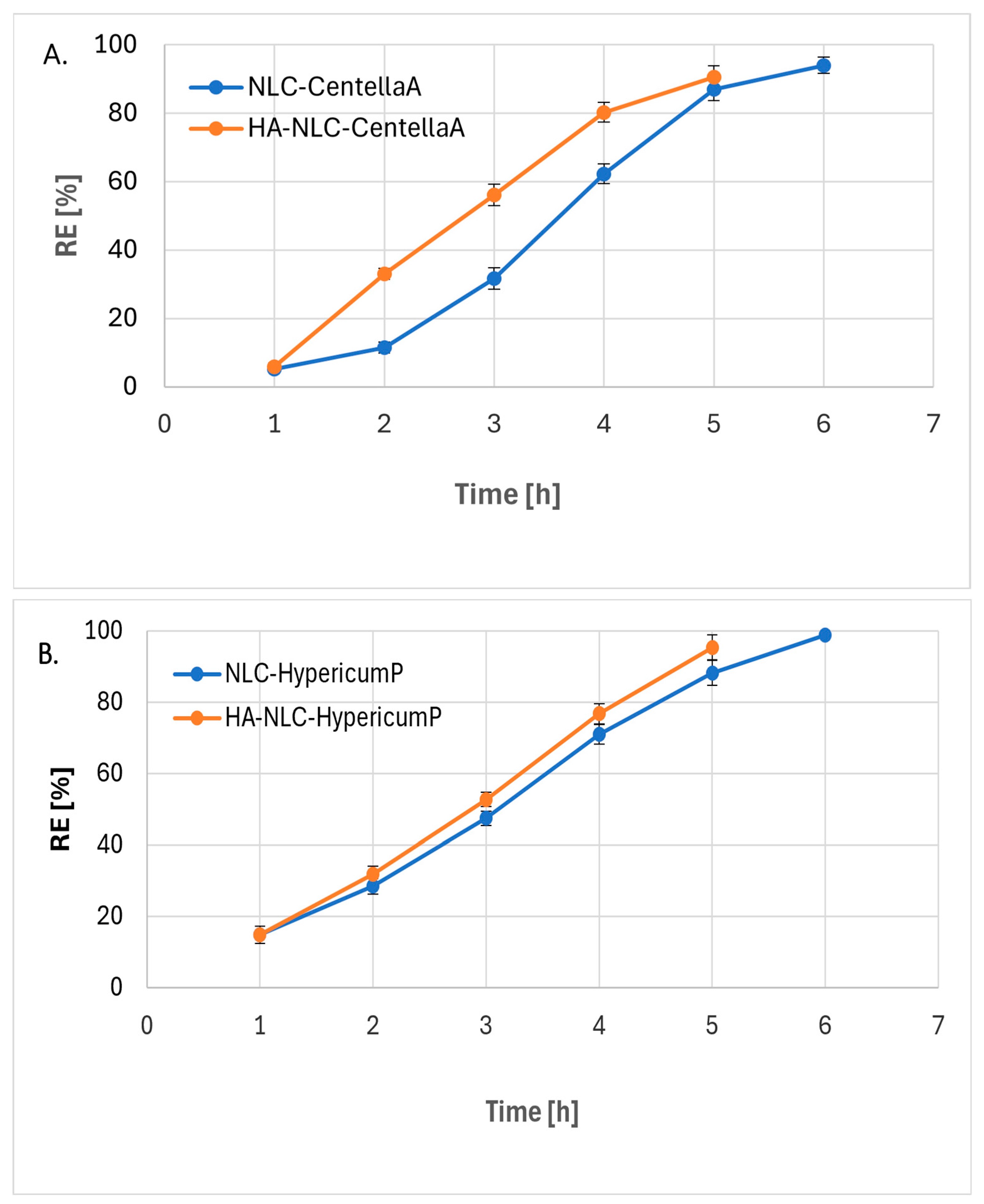

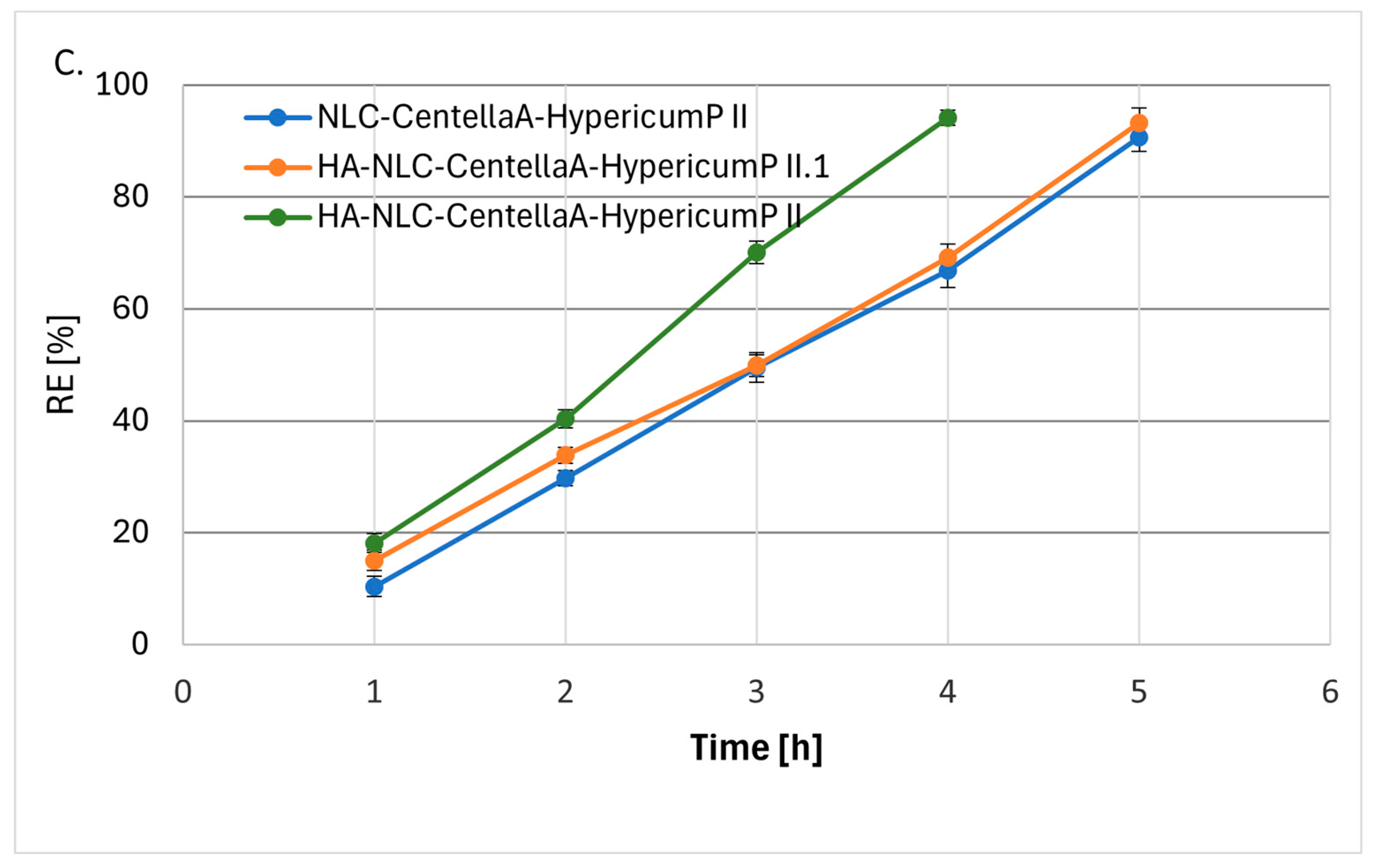

3.5. Phytochemical’s Release from NLC and HA Coated-NLC

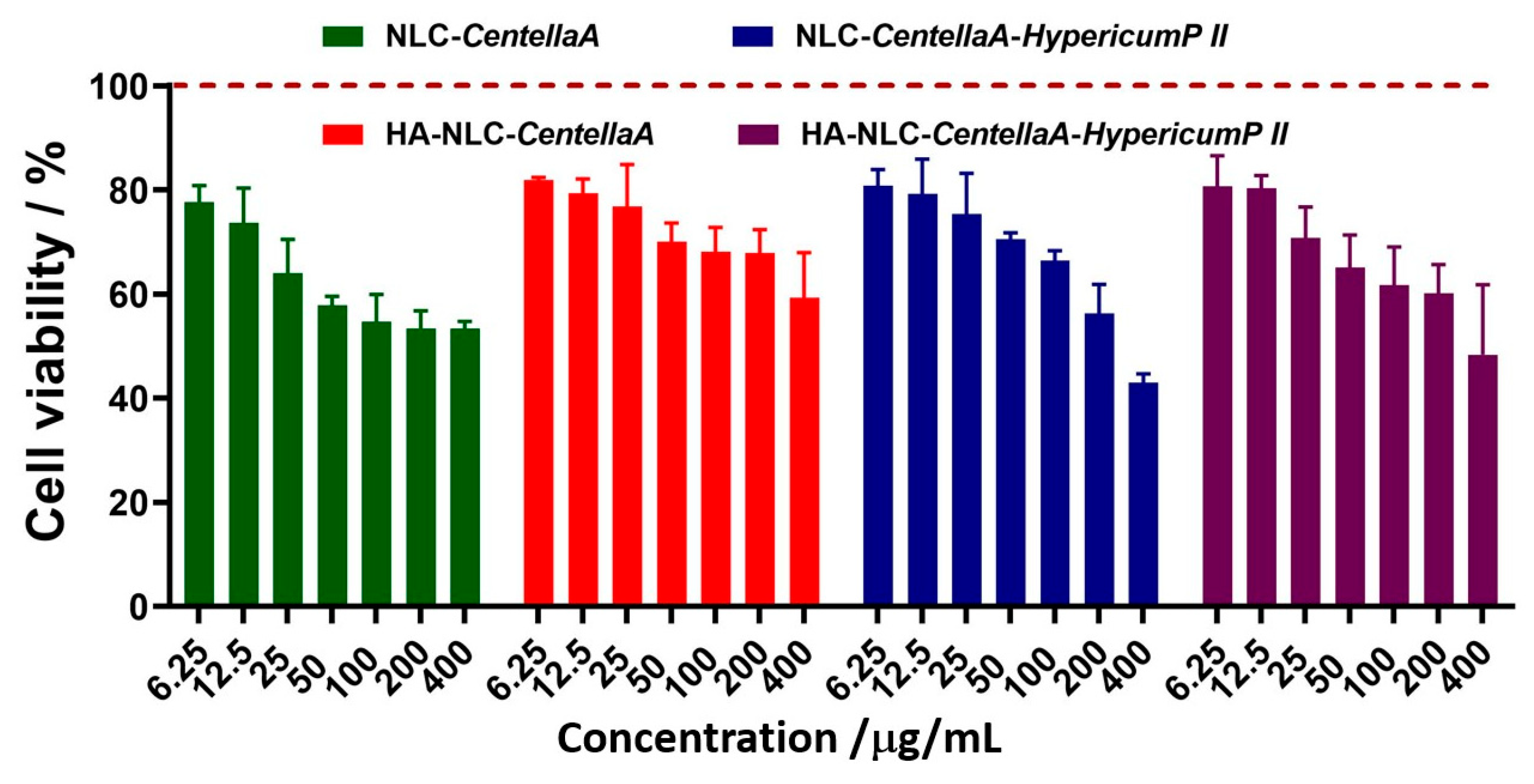

3.6. Cytotoxicity Assignment of NLC- and HA-NLC-Entrapping Herbal Extract

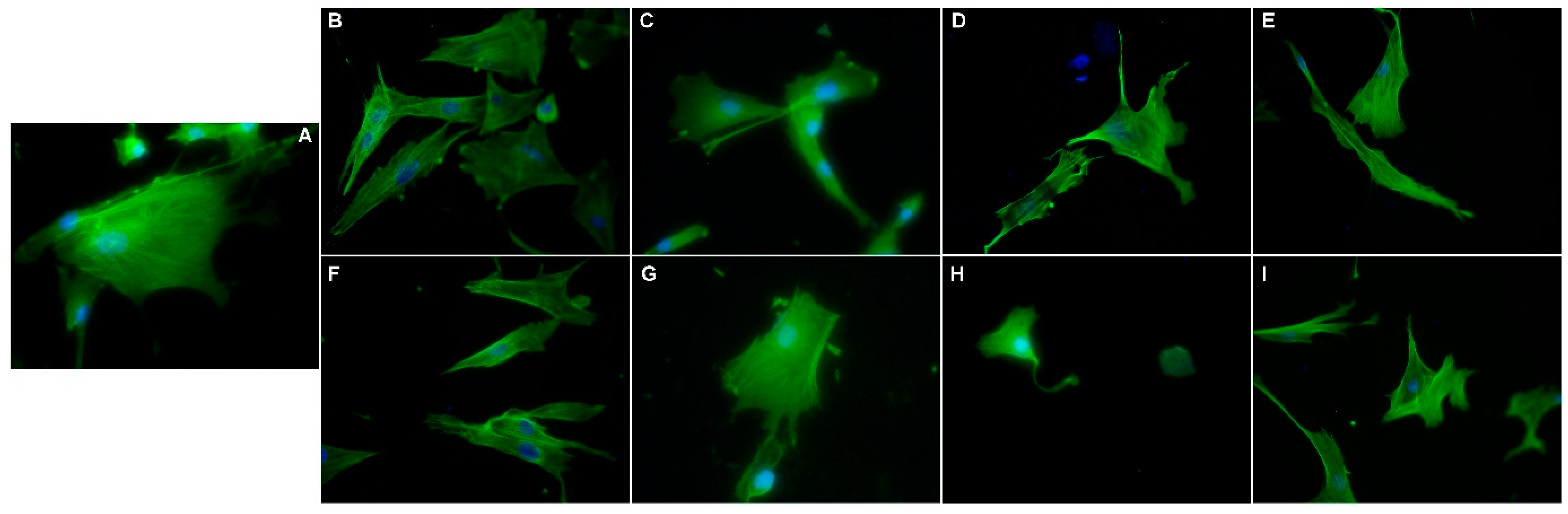

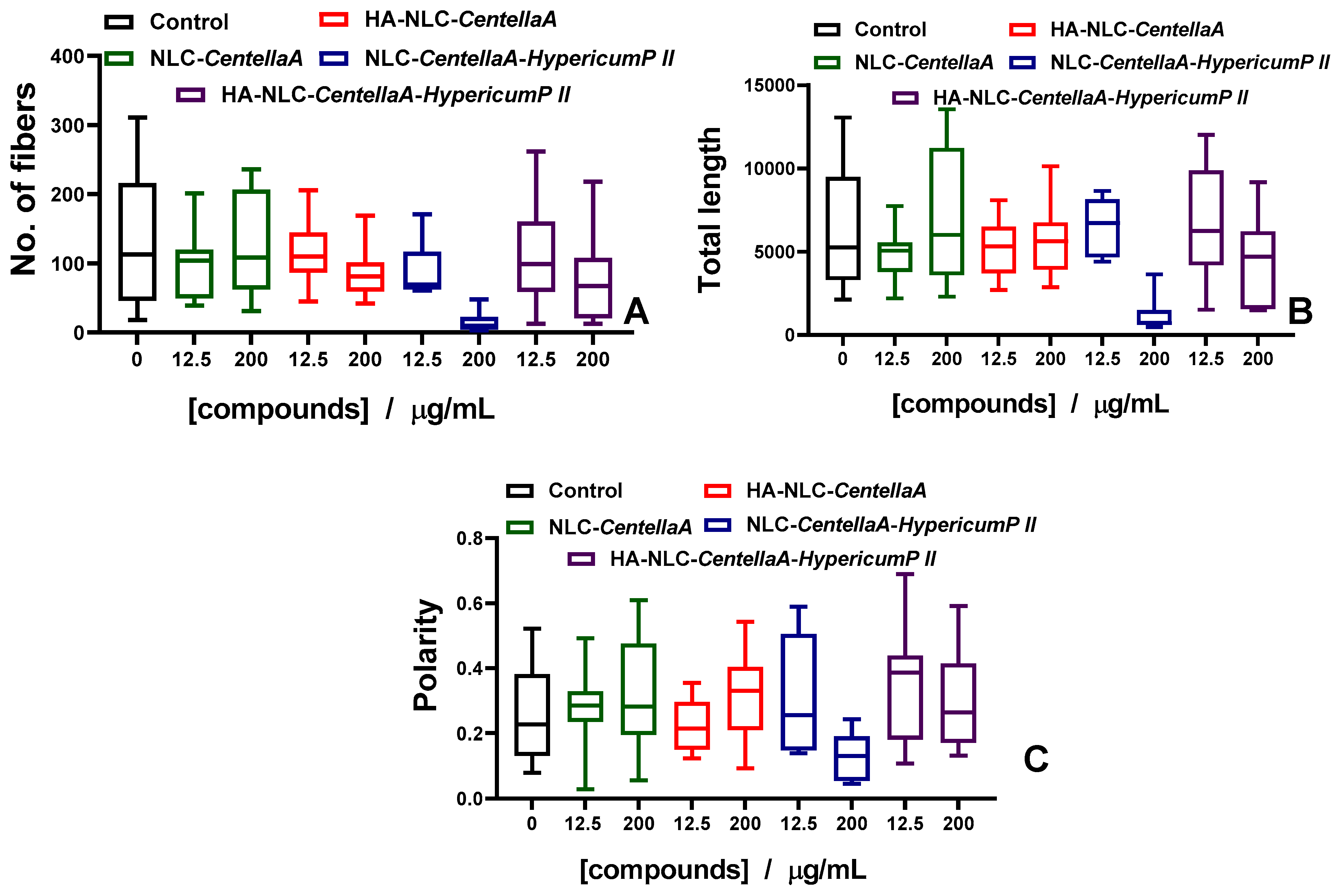

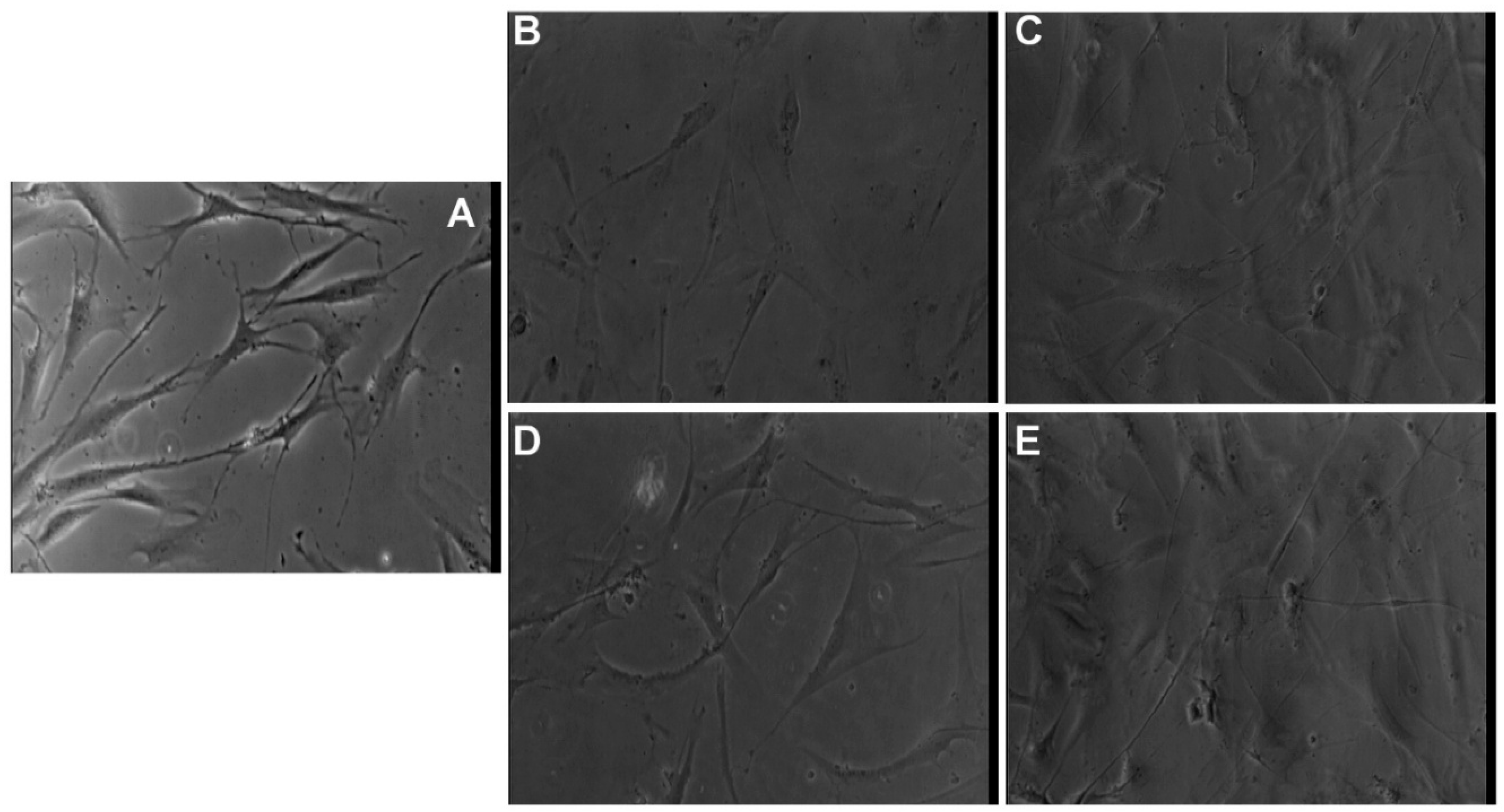

3.7. Morphological Evaluation of NLC- and HA-NLC-Herbal Extracts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prathumwon, C.; Anuchapreeda, S.; Kiattisin, K.; Panyajai, P.; Wichayapreechar, P.; Surh, Y.-J.; Ampasavate, C. Curcumin and EGCG combined formulation in nanostructured lipid carriers for anti-ageing applications. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 9, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.S.; Singh, W.S. Centella asiatica and its bioactive compounds: A comprehensive approach to managing hyperglycemia and associated disorders. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baljak, J.; Bogavac, M.; Karaman, M.; Srđenović Čonić, B.; Vučković, B.; Anačkov, G.; Kladar, N. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Hypericum Species—H. hirsutum, H. barbatum, H. rochelii. Plants 2024, 13, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.E.; Magana, A.A.; Lak, P.; Wright, K.M.; Quinn, J.; Stevens, J.F.; Maier, C.S.; Soumyanath, A. Centella asiatica—Phytochemistry and mechanisms of neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 17, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbati, F.A.; Ramezani, M.; Dehghan, R.; Amiri, M.S.; Moghadam, A.T.; Shakour, N.; Elyasi, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Emami, S.A. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Features of Centella asiatica: A Comprehensive Review. In Pharmacological Properties of Plant-Derived Natural Products and Implications for Human; Barreto, G.E., Sahebkar, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 451–499. [Google Scholar]

- Zainal, W.N.H.W.; Musahib, F.R.; Zulkeflee, N.S. Comparison of total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of Centella asiatica extracts obtained by three extraction techniques. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2019, 6, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska-Sikora, E.; Zielińska, A.; Dobros, N.; Paradowska, K.; Michalak, M. Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content and Antioxidant Activity of Hypericum perforatum L. (St. John’s Wort) Extracts for Potential Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Anderson, L.A.; Phillipson, J.D. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): A review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 583–768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, S.; Chandel, R.; Kaur, R.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.; Janghu, S.; Kaur, A.; Kumar, V. The flower of Hypericum perforatum L.: A traditional source of bioactives for new food and pharmaceutical applications. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 110, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algül, D.; Kılıç, E.; Özkan, F.; Uzuner, Y.Y. Wound Healing Effects of New Cream Formulations with Herbal Ingredients. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinli, E.; Demir, B.; Goksu, H. Preparation of Centella asiatica (L.) and Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort) Plant Extracts and Development of Anti-Aging Herbal Cream Formulations. Int. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. Res. 2023, 4, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC), European Union Herbal Monograph on Hypericum perforatum L., herba—Revision 1, European Medicines Agency, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, EMA/HMPC/7695/2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-monograph/final-european-union-herbal-monograph-hypericum-perforatum-l-herba-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Diniz, L.R.L.; Calado, L.L.; Duarte, A.B.S.; de Sousa, D.P. Centella asiatica and Its Metabolite Asiatic Acid: Wound Healing Effects and Therapeutic Potential. Metabolites 2023, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues da Rocha, P.B.; dos Santos Souza, B.; Marquez Andrade, L.; dos Anjos, J.L.V.; Mendanha, S.A.; Alonso, A.; Marreto, R.N.; Taveira, S.F. Enhanced asiaticoside skin permeation by Centella asiatica-loaded lipid nanoparticles: Effects of extract type and study of stratum corneum lipid dynamics. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 50, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacatusu, I.; Istrati, D.; Bordei, N.; Popescu, M.; Seciu, A.M.; Panteli, L.M.; Badea, N. Synergism of plant extract and vegetable oils-based lipid nanocarriers: Emerging trends in development of advanced cosmetic prototype products. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 108, 110412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajoriya, V.; Gupta, R.; Vengurlekar, S.; Singh, U.S. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs): A promising candidate for lung cancer targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 123986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacatusu, I.; Iordache, T.A.; Mihaila, M.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Pop, A.L.; Badea, N. Multifaced role of dual herbal principles loaded-lipid nanocarriers in providing high therapeutic efficacity. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sharma, A.; Jain, V. An Overview of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers and its Application in Drug Delivery through Different Routes. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 13, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalkhani, O.; Pires, P.C.; Mohammadi, M.; Babaie, S.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Hamishehkar, H. Nanogel containing gamma-oryzanol-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers and TiO2/MBBT: A synergistic nanotechnological approach of potent natural antioxidants and nanosized UV filters for skin protection. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haririan, Y.; Elahi, A.; Shadman-Manesh, V.; Rezaei, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Asefnejad, A. Advanced nanostructured biomaterials for accelerated wound healing: Insights into biological interactions and therapeutic innovations: A comprehensive review. Mater. Des. 2025, 258, 114698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orue, G.I.; Gainza, G.; Girbau, C.; Rodrigo, A.; Aguirre, A.; José, J.; Pedraz, J.; Igartua, M.; Hernandez, R. LL37 Loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC): A new strategy for the topical treatment of chronic wounds. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 108, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Jeong, M.; Na, Y.G.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.K.; Cho, C.W. An EGF- and curcumin-Co-encapsulated nanostructured lipid carrier accelerates chronic-wound healing in diabetic rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathoni, N.; Suhandi, C.; Elamin, K.M.; Lesmana, R.; Hasan, N.; Mohammed, A.F.A.; El-Rayyes, A.; Wilar, G. Advancements and Challenges of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Wound Healing Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 8091–8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, M.; Badea, N.; Birliga, M.; Bostan, M.; Albu Kaya, M.G.; Lacatusu, I. Ginkgo Biloba and Green Tea Polyphenols Captured into Collagen–Lipid Nanocarriers: A Promising Synergistically Approach for Apoptosis Activation and Tumoral Cell Cycle Arrest. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasy, N.K.A.; Sallam, M.A.; Ragab, D.; Abdelmonsif, D.A.; Aly, R.G.; Abdelfattah, E.-Z.A.; Elkhodairy, K.A. CD44-targeted hyaluronic acid-coated imiquimod lipid nanocapsules foster the efficacy against skin cancer: Attempt to conquer unfavorable side effects. Int. J. Bio. Macromol. 2025, 290, 138895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Jiang, X.; Xia, Y.; Qi, P.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Tian, X. Hyaluronic acid-conjugated lipid nanocarriers in advancing cancer therapy: A review. Int. J. Bio. Macromol. 2025, 299, 140146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Spicer, A.P. Hyaluronan: A multifunctional, megaDalton, stealth molecule. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopan, G.; Jose, J.; Khot, K.B.; Bandiwadekar, A.; Deshpande, N.S. Hyaluronic acid-based hesperidin nanostructured lipid carriers loaded dissolving microneedles: A localized delivery approach loaded for the management of obesity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 140948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Garg, A. Development and evaluation of hyaluronic acid conjugated tacrolimus-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers using moringa oleifera seed oil as liquid lipid. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 95, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleje, I.R.; Di Filippo, L.D.; Luiz, M.T.; Capaldi Fortunato, G.; Portuondo, D.L.; Freitas da Silva, M.; Carlos, I.Z.; Duarte, J.L.; Chorilli, M. Design and in vitro cytotoxicity of docetaxel-loaded hyaluronic acid-coated nanostructured lipid carriers in breast cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 110, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhao, X.; Xu, L.; Teng, C.; Li, Y. Hyaluronic acid-decorated lipid nanocarriers as novel vehicles for curcumin: Improved stability, cellular absorption, and anti-inflammatory effects. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Bhati, H.; Vanshita, S.; Bajpai, M. Recent insights into therapeutic potential and nanostructured carrier systems of Centella asiatica: An evidence-based review. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 10, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.M.; Pizzol, C.D.; Monteiro, F.B.F.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.B.; Andrade, G.P.; Ribeiro, A.O.; Perussi, J.R. Hypericin encapsulated in solid lipid nanoparticles: Phototoxicity and photodynamic efficiency. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2013, 125, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, T.; Fadel, M.; Fahmy, R.; Kassab, K. Evaluation of hypericin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: Physicochemical properties, photostability and phototoxicity. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2010, 17, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.R.; Oshiro-Junior, J.A.; Rodero, C.F.; Boni, F.I.; Sousa Araújo, V.H.; Bauab, T.M.; Nicholas, D.; Callan, J.F.; Chorilli, M. Photodynamic therapy-mediated hypericin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers against vulvovaginal candidiasis. J. Med. Mycol. 2022, 32, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacatusu, I.; Badea, N.; Badea, G.; Mihaila, M.; Ott, C.; Stan, R.; Meghea, A. Advanced bioactive lipid nanocarriers loaded with natural and synthetic anti-inflammatory actives. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 200, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculae, G.; Lacatusu, I.; Badea, N.; Oprea, O.; Meghea, A. Optimization of lipid nanoparticles composition for sunscreen encapsulation. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2013, 75, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14502-1; Determination of Substances Characteristic of Green and Black Tea, Part 1: Content of Total Polyphenols in Tea—Colorimetric Method Using Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent, First Edition. ISO (International Organization for Standardization): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Tincu, R.; Mihaila, M.; Bostan, M.; Istrati, D.; Badea, N.; Lacatusu, I. Hybrid Albumin Decorated Lipid-Nanocarrier-Mediated Delivery of Polyphenol-Rich Sambucus nigra L. in a Potential Multiple Antitumoural Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, S.; Murthy, P.N.; Nath, L.; Chowdhury, P. Kinetic modelling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2010, 67, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Sowa, I.; Mołdoch, J.; Dresler, S.; Kubrak, T.; Soluch, A.; Szczepanek, D.; Strzemski, M.; Paduch, R.; Wójciak, M. Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant Activity, and Protective Effect against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress of Carlina vulgaris Extract. Molecules 2023, 28, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisă, R.; Rusu, C.M.; Deftu, A.T.; Bacalum, M.; Radu, M.; Radu, B.M. Are You a Friend or an Enemy? The Dual Action of Methylglyoxal on Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Aldasoro, C.C.; Wilson, I.; Prise, V.E.; Barber, P.R.; Ameer-Beg, M.; Vojnovic, B.; Cunningham, V.J.; Tozer, G.M. Estimation of Apparent Tumor Vascular Permeability from Multiphoton Fluorescence Microscopic Images of P22 Rat Sarcomas In Vivo. Microcirculation 2010, 15, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grada, A.; Otero-Vinas, M.; Prieto-Castrillo, F.; Obagi, Z.; Falanga, V. Research Techniques Made Simple: Analysis of Collective Cell Migration Using the Wound Healing Assay. J. Investig. Dermatol 2017, 137, e11–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.H. Comprehensive Insights into Keloid Pathogenesis and Advanced Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, K.J.; Yadav, M.; Alishahedani, M.E.; Freeman, A.F.; Myles, I.A. Differential responses to folic acid in an established keloid fibroblast cell line are mediated by JAK1/2 and STAT3. Clin. Trial. 2021, 16, e0248011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qu, M.; Xu, L.; Wu, X.; Gao, Z.; Gu, T.; Zhang, W.; Ding, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.L. Sorafenib exerts an anti-keloid activity by antagonizing TGF-β/Smad and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaity, A.; Albakri, K.; Al-Dardery, N.M.; Yousef, Y.A.S.; Foppiani, J.A.; Lin, S.J. Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Therapy in Hypertrophic and Keloid Scars: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies. Plast. Surg. 2025, 33, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, W.; Pan, M.; Wang, C.; Wu, W.; Zhu, S. Wnt2 knock down by RNAi inhibits the proliferation of in vitro-cultured human keloid fibroblasts. Medicine 2018, 97, e12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Lacatusu, I.; Badea, G.; Grafu, I.A.; Istrati, D.; Babeanu, N.; Stan, R.; Badea, N.; Meghea, A. Exploitation of amaranth oil fractions enriched in squalene for dual delivery of hydrophilic and lipophilic actives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, N.; Shrestha, P.; Khadka, B.; Mondal, M.H.; Saha, B.; Bhattarai, A. A Review of Biopolymers’ Utility as Emulsion Stabilizers. Polymers 2022, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Srivastav, P.P. Encapsulation of Centella asiatica leaf extract in liposome: Study on structural stability, degradation kinetics and fate of bioactive compounds during storage. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacatusu, I.; Badea, N.; Badea, G.; Brasoveanu, L.; Stan, R.; Ott, C.; Oprea, O.; Meghea, A. Ivy leaves extract based—Lipid nanocarriers and their bioefficacy on antioxidant and antitumor activities. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 77243–77255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, A.; Sharma, K.; Dhasmana, D.; Garg, N.; Siril, F.P. Preparation, characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity of fenofibrate and nabumetone loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 106, 110184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjes, H.; Unruh, T. Characterization of lipid nanoparticles by differential scanning calorimetry, X-ray and neutron scattering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanian, Y.; Goli, S.A.H.; Varshosaz, J.; Sahafi, S.M. Formulation and characterization of novel nanostructured lipid carriers made from beeswax, propolis wax and pomegranate seed oil. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, A.; da Ana, R.; Fonseca, J.; Szalata, M.; Wielgus, K.; Fathi, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Staszewski, R.; Karczewski, J.; Souto, E.B. Phytocannabinoids: Chromatographic Screening of Cannabinoids and Loading into Lipid Nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirova, Y.; Gugleva, V.; Stoeva, S.; Kolev, I.; Nikolova, R.; Marudova, M.; Nikolova, K.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Hristova, M.; Andonova, V. Bigel Formulations of Nanoencapsulated St. John’s Wort Extract—An Approach for Enhanced Wound Healing. Gels 2023, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhua, J.; Rena, Z.; Zhang, G.; Guoa, X.; Ma, D. Comparative study of the H-bond and FTIR spectra between 2,2-hydroxymethyl propionic acid and 2,2-hydroxymethyl butanoic acid. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006, 63, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Méndez, R.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; González-Ballesteros, N. Flower, stem, and leaf extracts from Hypericum perforatum L. to synthesize gold nanoparticles: Effectiveness and antioxidant activity. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 32, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanifar, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Assadpour, E. Encapsulation of olive leaf phenolics within electrosprayed whey protein nanoparticles; production and characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, N.; Harini, K.; Joseph, M.; Sangeetha, R.; Venkatachalam, P. A Comparison of microwave assisted medicinal plant extractions for detection of their phyto-compounds through qualitative phytochemical and FTIR analyses. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2019, 43, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izza, N.; Watanabe, N.; Okamoto, Y.; Wibisono, Y.; Umakoshi, H. Characterization of entrapment behavior of polyphenols in nanostructured lipid carriers and its effect on their antioxidative activity. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022, 134, 269e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirova, Y.; Ivanova, N.; Ermenlieva, N.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Simeonova, L.; Metodiev, M.; Gugleva, V.; Andonova, V. Antimicrobial and Antiherpetic Properties of Nanoencapsulated Hypericum perforatum Extract. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S.H.; Doroudi, A. Review of the antioxidant potential of flavonoids as a subgroup of polyphenols and partial substitute for synthetic antioxidants. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2023, 13, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.A.; Ferreres, F.; Malva, J.O.; Dias, A.C.P. Phytochemical and antioxidant characterization of Hypericum perforatum alcoholic extracts. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orčić, D.Z.; Mimica-Dukić, N.M.; Francišković, M.M.; Petrović, S.S.; Jovin, E.Đ. Antioxidant activity relationship of phenolic compounds in Hypericum perforatum L. Chem. Cent. J. 2011, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, A.; Alghoraibi, I.; Zein, R.; Kraft, S.; Dräger, G.; Walter, J.-G.; Scheper, T. Identification of Major Constituents of Hypericum perforatum L. Extracts in Syria by Development of a Rapid, Simple, and Reproducible HPLC-ESI-Q-TOF MS Analysis and Their Antioxidant Activities. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 13475–13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneja, S.; Capalash, N.; Sharma, P. Hyaluronic acid as a tumor progression agent and a potential chemotherapeutic biomolecule against cancer: A review on its dual role. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NLC Formulations * | Herbal Extracts (g) | NLC: HA sol. (mL) | Zave (nm) ± SDS | PdI ± SDS | ξ (mV) ± SDS | EE ± SDS % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLC | - | - | 196.5 ± 2.23 | 0.226 ± 0.019 | −50.7 ± 1.76 | - |

| HA-NLC | - | 30:20 | 195.0 ± 4.02 | 0.303 ± 0.016 | −51.0 ± 1.50 | - |

| NLC-CentellaA | 1 | - | 206.1 ± 1.70 | 0.151 ± 0.013 | −54.6 ± 0.66 | 90.63 ± 0.14 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA | 1 | 30:20 | 202.2 ± 1.72 | 0.150 ± 0.011 | −58.7 ± 1.27 | 92.33 ± 0.05 |

| NLC-HypericumP | 1 | - | 201.3 ± 2.23 | 0.176 ± 0.015 | −61.7 ± 1.10 | 93.56 ± 0.04 |

| HA-NLC-HypericumP | 1 | 30:20 | 197.6 ± 1.91 | 0.163 ± 0.010 | −56.9 ± 2.02 | 95.26 ± 0.06 |

| NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP I | 0.8 g CentellaA + 0.2 g HypericumP | - | 221.4 ± 2.08 | 0.224 ± 0.006 | −49.8 ± 0.95 | 92.00 ± 0.40 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP I | 30:20 | 220.3 ± 1.74 | 0.190 ± 0.005 | −52.1 ± 0.46 | 92.81 ± 0.12 | |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP I.1 | 30:10 | 224.8 ± 0.78 | 0.211 ± 0.006 | −54.4 ± 1.68 | 92.23 ± 0.36 | |

| NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP II | 1 g CentellaA + 0.5 g HypericumP | - | 197.9 ± 4.06 | 0.185 ± 0.006 | −55.7 ± 0.61 | 89.52 ± 0.10 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP II | 30:20 | 198.5 ± 0.87 | 0.213 ± 0.008 | −54.9 ± 0.47 | 90.91 ± 0.05 | |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP II.1 | 30:10 | 193.0 ± 4.59 | 0.216 ± 0.015 | −53.9 ± 0.40 | 90.52 ± 0.21 |

| NLC and HA-NLC Formulations | Ordin 0 | Ordin1 | Higuchi | Hixson-Crowell | Peppas-Korsmeyer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | k0 | R2 | k1 | R2 | k2 | R2 | k3 | R2 | k4 | n | |

| NLC-CentellaA | 0.9467 | 17.728 | 0.8582 | 0.4742 | 0.9030 | 67.597 | 0.8745 | 0.0884 | 0.9747 | 1.4823 | 0.2772 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA | 0.9778 | 19.994 | 0.9231 | 0.4846 | 0.9946 | 70.999 | 0.9464 | 0.0860 | 0.9526 | 1.9841 | 0.2902 |

| NLC-HypericumP | 0.9924 | 17.335 | 0.8198 | 0.7928 | 0.9661 | 60.650 | 0.8867 | 0.0699 | 0.9936 | 2.6500 | 0.4432 |

| HA-NLC-HypericumP | 0.9942 | 19.524 | 0.863 | 0.6893 | 0.9766 | 66.226 | 0.8028 | 0.1117 | 0.9988 | 2.683 | 0.4268 |

| NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP | 0.9918 | 18.555 | 0.8933 | 0.5340 | 0.9833 | 64.428 | 0.8525 | 0.0786 | 0.9962 | 2.3920 | 0.3727 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP II | 0.9931 | 24.023 | 0.8916 | 0.861 | 0.9827 | 76.74 | 0.8476 | 0.1369 | 0.9985 | 2.8923 | 0.4157 |

| HA-NLC-CentellaA-HypericumP II.1 | 0.9945 | 18.448 | 0.8407 | 0.5835 | 0.9702 | 61.565 | 0.7894 | 0.090 | 0.9984 | 2.7164 | 0.4489 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lăcătusu, I.; Bacalum, M.; Stan, D.L.; Oprea, O.-C.; Neagu, M.; Alexandru, G.; Prisacari, M.; Badea, N. Advanced Hybrid Polysaccharide—Lipid Nanocarriers for Bioactivity Improvement of Phytochemicals from Centella asiatica and Hypericum perforatum. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010048

Lăcătusu I, Bacalum M, Stan DL, Oprea O-C, Neagu M, Alexandru G, Prisacari M, Badea N. Advanced Hybrid Polysaccharide—Lipid Nanocarriers for Bioactivity Improvement of Phytochemicals from Centella asiatica and Hypericum perforatum. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleLăcătusu, Ioana, Mihaela Bacalum, Diana Lavinia Stan, Ovidiu-Cristian Oprea, Mihaela Neagu, Georgeta Alexandru, Mihaela Prisacari, and Nicoleta Badea. 2026. "Advanced Hybrid Polysaccharide—Lipid Nanocarriers for Bioactivity Improvement of Phytochemicals from Centella asiatica and Hypericum perforatum" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010048

APA StyleLăcătusu, I., Bacalum, M., Stan, D. L., Oprea, O.-C., Neagu, M., Alexandru, G., Prisacari, M., & Badea, N. (2026). Advanced Hybrid Polysaccharide—Lipid Nanocarriers for Bioactivity Improvement of Phytochemicals from Centella asiatica and Hypericum perforatum. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010048