Waterproof Fabric with Copper Ion-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Coatings for Jellyfish Repellency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agents and Materials

2.2. Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Synthesis and Spraying

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) of Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

2.4. Drug Release Profile Testing

- Pn represents the percentage of drug released at each time point;

- N represents the concentration of released repellent in the system at each time point;

- V0 is the total volume of the solution, fixed at 1000 mL;

- V is the volume collected each time, fixed at 5 mL;

- Q is the mass of the repellent adhered to the fabric (calculated based on the working solution ratio).

2.5. Nanoparticle Adhesion Testing

- WΔ represents the theoretical initial adhesion weight of electrosprayed particles;

- W0 represents the initial weight of the fabric;

- Wa represents the weight of the fabric after electrospraying;

- W10 represents the weight of the electrospray fabric after 10 wash cycles;

- Wx represents the retained particle weight after 10 wash cycles;

- R represents the particle retention rate after 10 wash cycles.

2.6. Biocompatibility and Safety Examination

2.7. Detection of Jellyfish Repellency Efficiency

- P: Repellency rate (%);

- M: Number of jellyfish that escaped to zones outside the repellent-treated area by the end of the test;

- K: Number of jellyfish that became immobilized by the end of the test;

- N: Total number of jellyfish across all three groups by the end of the test.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

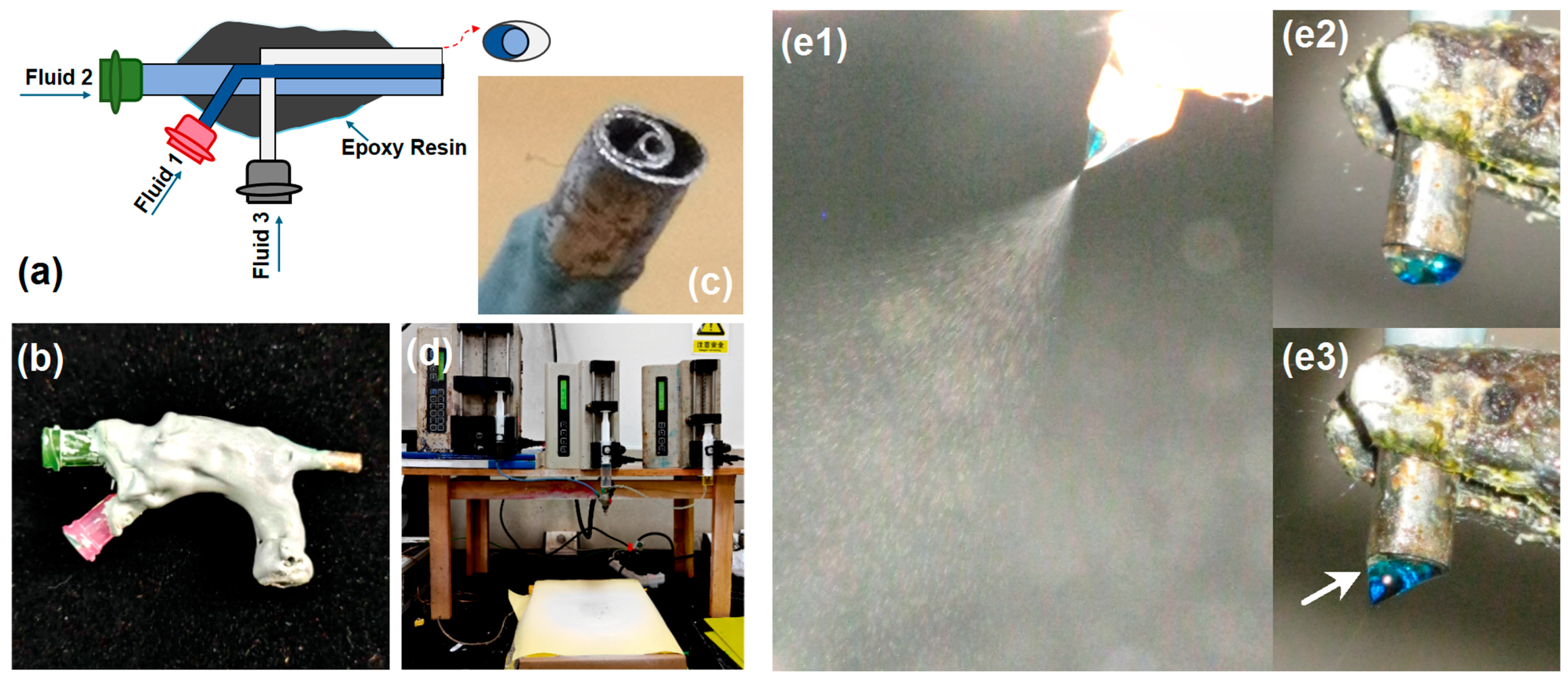

3.1. Implementation of Multi-Fluid Electrospraying

3.2. Characterization of Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

3.3. Drug Release Profile of Cu2+-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

3.4. Adhesion Property of Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

3.5. Biocompatibility of the Fabric Coated with Cu2+-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

3.6. Jellyfish Repellency Efficiency of the Fabric Coated with Cu2+-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| TPU | Thermoplastic polyurethane |

| TFE | Trifluoroethanol |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Li, B.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, J. Advances in Jellyfish Sting Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Aquatic Antagonists: Jellyfish Stings. Cutis 2022, 109, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Zou, S.; Song, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; He, Q.; Zhang, L. Protective Effects of Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) against the Jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai Envenoming. Toxins 2023, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershwin, L.; Dabinett, K. Comparison of Eight Types of Protective Clothing against Irukandji Jellyfish Stings. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 251, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Tang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, M.; Chen, X.; Pozzolina, M.; Höfer, J.; Ma, X.; et al. Copper-induced oxidative stress inhibits asexual reproduction of Aurelia coerulea polyps. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 285, 117112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, L. Intervention effects of five cations and their correction on hemolytic activity of tentacle extract from the jellyfish Cyanea capillata. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, H.; Xing, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Cai, S.; Li, P. Partial characterization of the hemolytic activity of the nematocyst venom from the jellyfish Cyanea nozakii Kishinouye. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 1750–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, C.; Li, R.; Xing, R.; Liu, S.; Li, P. Factors influencing hemolytic activity of venom from the jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum Kishinouye. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yu, H.; Feng, J.; Xing, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Qin, Y.; Li, K.; Li, P. Two-step purification and in vitro characterization of a hemolysin from the venom of jellyfish Cyanea nozakii Kishinouye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Ma, Y. Combined effects of ocean acidification and copper exposure on the polyps of moon jellyfish Aurelia coerulea. Ecotoxicology 2025, 34, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado, B.; Valero, N.; Roca-Pérez, L.; Bernabeu-Berni, E.; Andreu-Sánchez, O. Investigation of Metal Toxicity on Microalgae Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Hipersaline Zooplankter Artemia salina, and Jellyfish Aurelia aurita. Toxics 2023, 11, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, U.H.; Nisa, Z.U.; Riaz, A.; Faheem, M.S.; Batool, R.; Ullah, I.; Sabir, Q.U.A. Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Finishing on Dyeing Properties of Newly Synthesized Reactive Dye Applied on Cellulosic Fabric. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemenčič, D.; Tomšič, B.; Kovač, F.; Žerjav, M.; Simončič, A.; Simončič, B. Antimicrobial wool, polyester and a wool/polyester blend created by silver particles embedded in a silica matrix. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 111, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, J.; Santo, U.S.; Chekini, M.; Cha, M.; de Moura, A.F.; Kotov, N.A. Chiromagnetic nanoparticles and gels. Science 2018, 359, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, N.D.; Acar, H.; Wilhelm, S. Concepts of nanoparticle cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and kinetics in nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 143, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, K.; Taratula, O.; Farsad, K. Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 799–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Zaks, T.; Langer, R.; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Xie, R.; Wang, C.; Gai, S.; He, F.; Yang, D.; Yang, P.; Lin, J. Magnetic Targeting, Tumor Microenvironment-Responsive Intelligent Nanocatalysts for Enhanced Tumor Ablation. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11000–11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Cai, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, S. Advanced application of stimuli-responsive drug delivery system for inflammatory arthritis treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Yu, Y.; Han, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, D.; Qian, Z. Polymeric Nanoparticles with ROS-Responsive Prodrug and Platinum Nanozyme for Enhanced Chemophotodynamic Therapy of Colon Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sunil, D.; Ningthoujam, R.S. Hypoxia-responsive nanoparticle based drug delivery systems in cancer therapy: An up-to-date review. J. Control. Release 2020, 319, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Z. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for stimuli-responsive controlled drug delivery: Advances, challenges, and outlook. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 12, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Rengasamy, R.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Mishra, G.; Singh, C.J. Study on antimicrobial properties of fabrics made from embedded silver nanocomposite polyester fibre-yarns and coated with silver nanoparticles. J. Text. Inst. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Niu, Y. Preparation of Catechol-Based Nanocapsules with pH Responsiveness and Their Application on Cotton Fabrics. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.C.; Lahann, J. Progress of Multicompartmental Particles for Medical Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1701319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, L.; Mao, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, J. Controllable Synthesis of Multicompartmental Particles Using 3D Microfluidics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 59, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Gao, S.; Qu, Q.; Xiong, R.; Braeckmans, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Zhang, Y.S.; Huang, C. Faithful Fabrication of Biocompatible Multicompartmental Memomicrospheres for Digitally Color-Tunable Barcoding. Small 2020, 16, 1907586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.-G.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Li, H. A Core-Janus-Sheath Micro-fluid Guided Spinneret, Its Apparatus and Spinning Protocols. Chinese Patent No. ZL201611122996.9, 14 December 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, D.-G.; Annie Bligh, S.W. A modified triaxial electrospinning for a high drug encapsulation efficiency of curcumin in ethylcellulose. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.R.; Noureen, E.; Collinson, S.R.; Taylor, P.G.; Shearman, G.C.; Rietdorf, K.; Chatterton, N.P. Enhancing the aqueous solubility of hemin at physiological pH through encapsulation within polyvinylpyrrolidone nanofibres. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 687, 126396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Yusufu, R.; Guan, Z.; Chen, T.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, X.; Lu, J.; Luo, M.; Wei, F. Multifunctional Bioactivity Electrospinning Nanofibers Encapsulating Emodin Provide A Potential Postoperative Management Strategy for Skin Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almotawa, R.Y.; Alhamid, G.; Badran, M.M.; Orfali, R.; Alomrani, A.H.; Tawfik, E.A.; Alzahrani, D.A.; Alfassam, H.A.; Ghaffar, S.; Fathaddin, A.; et al. Co-Delivery of Dragon’s Blood and Alkanna Tinctoria Extracts Using Electrospun Nanofibers: In Vitro and In Vivo Wound Healing Evaluation in Diabetic Rat Model. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, B.; Rohani, S. Local Delivery of Ginger Extract via a Nanofibrous Membrane Suppresses Human Skin Melanoma B16F10 Cells Growth via Targeting Ras/ERK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways: An In Vitro Study. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2024, 23, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumal, V.; Sujatha, K.; Dhanush, R.; Sowmya, C. Electrospun Nanofiber Films Containing Hesperidin and Ofloxacin for the Inhibition of Inflammation and Psoriasis: A Potential In Vitro Study. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2025, 22, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Ijaz, M.; Rafique, S.; Yasin, H.; Mushtaq, M.; Khan, A.K.; Khan, M.; Nasir, B.; Murtaza, G. Cefadroxil-Mupirocin Integrated Electrospun Nanofiber Films for Burn Wound Therapy. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-S.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Yu, D.-G.; He, H.; Liu, P.; Du, K. Electrospun nanofibers and their application as sensors for healthcare. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1533367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.-G.; Liu, J. Multiple-Chamber Nanostructures for Drug Delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2025, 23, vi–vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutunkova, M.; Katsnelson, B.; Privalova, L.; Gurvich, V.; Konysheva, L.; Shur, V.; Shishkina, E.; Minigalieva, I.; Solovjeva, S.; Grebenkina, S.; et al. On the contribution of the phagocytosis and the solubilization to the iron oxide nanoparticles retention in and elimination from lungs under long-term inhalation exposure. Toxicology 2016, 363–364, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birsa, L.M.; Verity, P.G.; Lee, R.F. Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 151, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Ding, D.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Yu, J.; Jiang, F.; et al. Electrospun tri-layer core-sheath nanofibrous coating for sequential treatment of postoperative complications in orthopedic implants. Small 2025, 21, e05523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; He, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, D.-G. Coaxial electrospun ZIF-8@PAN nanofiber membranes for tetracycline and doxycycline adsorption in wastewater: Kinetic, isothermal and thermodynamic studies. Adv. Mater. Interf. 2025, 12, e00364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.G.; Zhou, J. Electrospun multi-chamber nanostructures for sustainable biobased chemical nanofibers. Next Mater 2024, 2, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Gong, W.; Guo, Q.; Liu, H.; Yu, D.-G. Synergistic effects of radical distributions of soluble and insoluble polymers within electrospun nanofibers for an extending release of ferulic acid. Polymers 2024, 16, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Gong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yu, D.-G.; Yi, T. Reverse Gradient Distributions of Drug and Polymer Molecules within Electrospun Core–Shell Nanofibers for Sustained Release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Wang, M.-L.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.-G.; Bligh, S.W.A. Shell Distribution of Vitamin K3 within Reinforced Electrospun Nanofibers for Improved Photo-Antibacterial Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhou, K.; Xia, Y.; Qian, C.; Yu, D.-G.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Y. Electrospun Trilayer Eccentric Janus Nanofibers for A Combined Treatment of Periodontitis. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, W.; Gong, W.; Lu, Y.; Yu, D.-G.; Liu, P. Recent Progress of Electrospun Nanofibers as Burning Dressings. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 14374–14391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | W0 (g) | Wa (g) | WΔ (g) | W10 (g) | Wx (g) | R (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper chloride (n = 3) | 0.6389 | 0.7413 | 0.1024 | 0.7149 | 0.076 | 74.22 |

| 0.5628 | 0.6286 | 0.0658 | 0.6122 | 0.0494 | 75.08 | |

| 0.6058 | 0.7192 | 0.1134 | 0.6889 | 0.0831 | 73.28 | |

| Copper sulfate (n = 3) | 0.5883 | 0.665 | 0.0767 | 0.6374 | 0.0491 | 64.02 |

| 0.6763 | 0.7827 | 0.1064 | 0.7655 | 0.0892 | 83.83 | |

| 0.6898 | 0.7381 | 0.0483 | 0.7235 | 0.0337 | 69.77 | |

| Copper acetate (n = 3) | 0.6544 | 0.7848 | 0.1304 | 0.7722 | 0.1178 | 90.34 |

| 0.6667 | 0.697 | 0.0303 | 0.6858 | 0.0191 | 63.04 | |

| 0.6493 | 0.7753 | 0.126 | 0.7565 | 0.1072 | 85.08 |

| Group | Animal ID (Weight/g) | Skin Elicitation Phase Grade | Positive Elicitation Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | |||

| Blank control | 1 (351) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 (366) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 (312) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 (363) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 (329) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Treat | 1 (318) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 (342) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 (329) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4(327) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 (340) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 (347) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7 (325) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 (316) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9 (311) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 10 (340) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Positive control | 1 (349) | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 2 (328) | 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 (338) | 2 | 2 | ||

| 4 (357) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5 (366) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 (324) | 2 | 1 | ||

| 7 (320) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 8 (348) | 2 | 2 | ||

| 9 (359) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 10 (364) | 2 | 2 | ||

| Animal ID (Weight/g) | 1 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | |||||||||

| Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | Erythema/Edema | Total | |

| 1 (2410) | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 |

| 2 (2490) | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 |

| 3 (2630) | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 |

| Score mean | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Group | 100% Test Solution of the Sample | 50% Test Solution of the Sample | 25% Test Solution of the Sample | 12.5% Test Solution of the Sample | Negative Control | Positive Control | Blank Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.3955 | 0.4032 | 0.4190 | 0.4185 | 0.4262 | 0.4262 | 0.3730 |

| SD | 0.0387 | 0.0339 | 0.0258 | 0.0298 | 0.0340 | 0.0340 | 0.0254 |

| Survival rate (%) | 106.03 | 108.09 | 112.33 | 112.2 | 114.26 | 114.26 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Yao, R.; Zhao, H.; Yu, D.; Du, L.; Zou, S.; Zhu, Y. Waterproof Fabric with Copper Ion-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Coatings for Jellyfish Repellency. Pharmaceutics 2026, 18, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010047

Wang B, Yang M, Yao R, Zhao H, Yu D, Du L, Zou S, Zhu Y. Waterproof Fabric with Copper Ion-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Coatings for Jellyfish Repellency. Pharmaceutics. 2026; 18(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bo, Muzi Yang, Ruiqian Yao, Haixia Zhao, Dengguang Yu, Lin Du, Shuaijun Zou, and Yuanjie Zhu. 2026. "Waterproof Fabric with Copper Ion-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Coatings for Jellyfish Repellency" Pharmaceutics 18, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010047

APA StyleWang, B., Yang, M., Yao, R., Zhao, H., Yu, D., Du, L., Zou, S., & Zhu, Y. (2026). Waterproof Fabric with Copper Ion-Loaded Multicompartmental Nanoparticle Coatings for Jellyfish Repellency. Pharmaceutics, 18(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010047