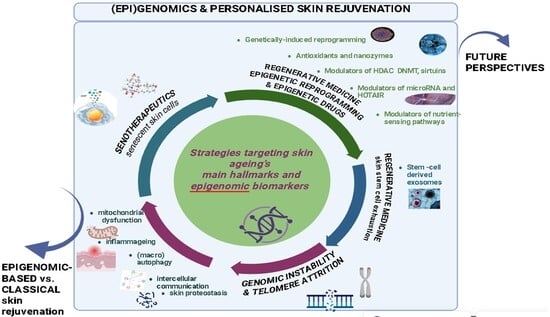

A State-of-the-Art Overview on (Epi)Genomics and Personalized Skin Rejuvenating Strategies

Abstract

1. Skin Ageing: Classification and Main Hallmarks

2. Clocks and Biomarkers in Skin Anti-Ageing Strategy Evaluation: Description and Clinical Relevance

3. Senotherapeutics Targeting Senescent Skin Cells

3.1. Senolytics and Senomorphics—Mechanisms of Action

3.2. Main Senotherapeutic Agents Preclinically and Clinically Tested

| Substance | Model and Dose Regimen | Mechanism/ Modified Biomarkers | Main Results and Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENOLYTICS | ||||

| Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q) | Mice model; oral 5 mg/kg D + 50 mg/kg Q, intermittent dosing; | ↓ p16, p21 ↓ SAβGAL ↓ SASP Bcl-2 inhibition | Attenuated fibrosis, cognitive decline, osteoarthritis, diabetic complications; Limited administration period, small size cohorts; no data on visible or structural skin parameters; no long-term safety data (especially on healthy cells); | [12,47,49] |

| Navitoclax (ABT263) | Preclinical/animal studies; early-stage topical formulation development: topical application of ABT-263 (Navitoclax) in aged mice; 5 day treatment; Murine models of lung fibrosis, osteoarthritis; 50 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks; | Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 inhibitor; ↓ senescent cell viability; ↓ p16INK4A | Improved dermal thickness and collagen organization; reduction in skin senescence markers; improved wound healing in aged mice; improved tissue function; Toxicity concerns; human topical safety/efficacy not established; thrombocytopenia as adverse effect in systemic administration; | [51,52,72] |

| BPTES | Mouse/human chimeric model (skin grafts of senescent human dermal fibroblasts were subcutaneously transplanted to nude mice); mice treated with BPTES or vehicle, intraperitoneal, for 30 days | ↓ SAβGal; ↓ p16, p21; ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8; ↓ MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-9 | Selective senolytic effects on aged dermal fibroblasts, sustained 1 month post-therapy; increased collagen density; increased cell proliferation in the dermis; decreased SASP. Limitations: small sample size; only male human skin grafts collected; unknown effects on the surface properties of human skin; risk of suppression of the skin T lymphocytes’ proliferation and risk of carcinogenesis | [66,67,68] |

| FOXO4-DRI peptide (FOXO4-D-retro- inverso-isoform peptide) | Preclinical animal studies; Clinical trial: 10 keloid skin samples (females); 7 normal skin samples (female participants) | Peptide-induced senescent cell apoptosis: disruption of FOXO4–p53 interaction | Mechanistic insights into FOXO4-DRI: down-regulation of p53-serine15 phosphorylation (p53-pS15); p53-pS15 translocation into cytoplasm; selective agents to induce apoptosis of senescent fibroblasts in both keloid fibroblast and organ culture senescent models. Improved skin regeneration and reduced ageing biomarkers; rejuvenate epidermal stem cell function, leading to improved skin barrier integrity and repair capacity; Delivery challenges; small cohorts | [69,70] |

| Fisetin | C57BL/6 mice; 100 mg/kg/day, 1 week on/1 week off | ↓ p16INK4A; Bcl-2 family inhibition | Improved vascular endothelial function and arterial stiffness | [54] |

| Cycloastragenol (CAG) | Aged mice; oral, 50 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks | ↓ Bcl-2, PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibition | Selective senescent cell clearance; improved cardiac and muscle function | [75] |

| 25-Hydroxycholesterol | Aged mice; i.p., 50 mg/kg/day 5 consecutive days | ↓ p16INK4A, ↓ IL-6, ↓ TNF-α | Reduced arterial stiffness and improved vascular reactivity | [76] |

| SENOMORPHICS | ||||

| Rapamycin/ sirolimus | Skin explants and 3D models; Human subjects, photoaged skin: topical; Mice model: intermittent or lifelong oral dosing (e.g., rapamycin 14 ppm in diet); | Inhibition of mTOR, NF-κB and SASP; ↓ p16INK4A ↓ IL-6, IL-8 in plasma; ↓ MMP-1 | Reduced wrinkles; improved ECM remodelling; extended lifespan, improved cardiac and cognitive function (mice model); Small cohort; reduced administration period | [55,56,57,62,63] |

| Metformin | HUVEC cells in vitro (0.5–2 mM); aged mice 50 mg/kg daily | ↑ AMPK, ↓ NF-κB, ↓ ROS | Reduced SASP, improved endothelial function | [60,61] |

| Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) | C57BL/6 male mice: 15 mg/kg/day oral | LOX inhibition, ↑ PPARα, ↑ AMPK | ~8–10% lifespan extension, improved metabolic parameters | [81] |

| Rutin | Aged mice; 50 mg/kg/day oral | Inhibits ATM–HIF1α–TRAF6 axis; ↓ IL-6 | Reduced vascular inflammation, enhanced chemotherapy efficacy | [77] |

| SENOMORPHIC AND SENOLYTIC (DUAL ACTION) | ||||

| OS-01 (Pep 14) | RCT | ↓ SASP ↓ IL-8 ↓ glycated IgG | Thickened the skin barrier, enhanced skin radiance/texture, diminished the wrinkles’ depth. Limited cohorts | [64,65] |

| Procyanidin C1 (PCC1) | ageing-related skin-fibrosis, murine models | inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation and suppression of multiple downstream signalling cascades (ERK/MAPK, AKT/mTOR and TGFβ/SMAD pathways) | Significant anti-fibrotic skin effects: reduced epidermal hyperplasia and thickness; reduced abnormal collagen deposition; restored the collagen I/III ratio human translation needs validation | [71,72,73] |

| PCC1 + Cellumiva™ (senolytic complex = procyanidin C1 + pterostilbene + spermidine) | Open-label RCT on 75 female healthy volunteers, aged 45–65; oral dietary supplement; once daily; 12 weeks | imaging technologies; feedback questionnaires | Good effects on skin barrier function and texture/radiance, while diminishing wrinkles; Limited safety data | [73,80] |

3.3. Critical Insights on Senotherapeutics as Skin Rejuvenating Strategy

4. Skin Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Genomic Instability and Telomere Attrition

- stimulation of reverse transcriptase telomerase, an enzyme responsible for biosynthesis of new telomeric DNA based on RNA template in highly proliferative skin cells like stem cells, using for instance as telomerase activator the compound TA-65 [8,42]. Moreover, liposomes with xenogenic DNA repair enzymes like photolyase isolated from microalgae Anacystis nidulans and T4 endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus have proven efficient due to a significant decrease in telomere shortening rates [11,33]; as well as liposomes with 8-oxoguanine glycosylase photolyase (OGG1) which have demonstrated an essential role in reducing the biomarker 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine of oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunctions [58,84];

- recovering of the multi-protein shelterin complex that is essential for stabilization of chromosomes and for their protection against being detected as double-stranded breaks. The TRF2 protein of shelterin complex is involved in telomere capping and DDR inhibition; TRF2 deficiency triggers the activation of p53 signalling pathway and cellular apoptosis. In this regard, topical application of TRF2 might have a protective role in telomeric DNA [58,85,87];

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide NAD+ boosters (such as NAD+ precursors: nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide), which, like telomerase activators (e.g., compound TA-65), support DNA integrity and cellular longevity, help slow DNA damage accumulation; however, direct evidence in human skin is limited and their effects may be systemic [59].

5. Regenerative Medicine Targeting Skin Stem Cell Exhaustion: Fundamentals and Clinical Progress

6. Regenerative Medicine Focused on Epigenetic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Drugs

6.1. Fundamentals of Epigenetic Reprogramming as (Skin) Rejuvenation Strategy

- ✓

- changes in DNA methylation pattern at cytosine residues, which are highly tissue-and age-specific;

- ✓

- post-translational covalent alterations of histones (i.e., methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation), decreased proportion of core histones and the incorporation of non-canonical histones;

- ✓

- reduced global heterochromatin and heterochromatin structural modifications with accumulation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF);

- ✓

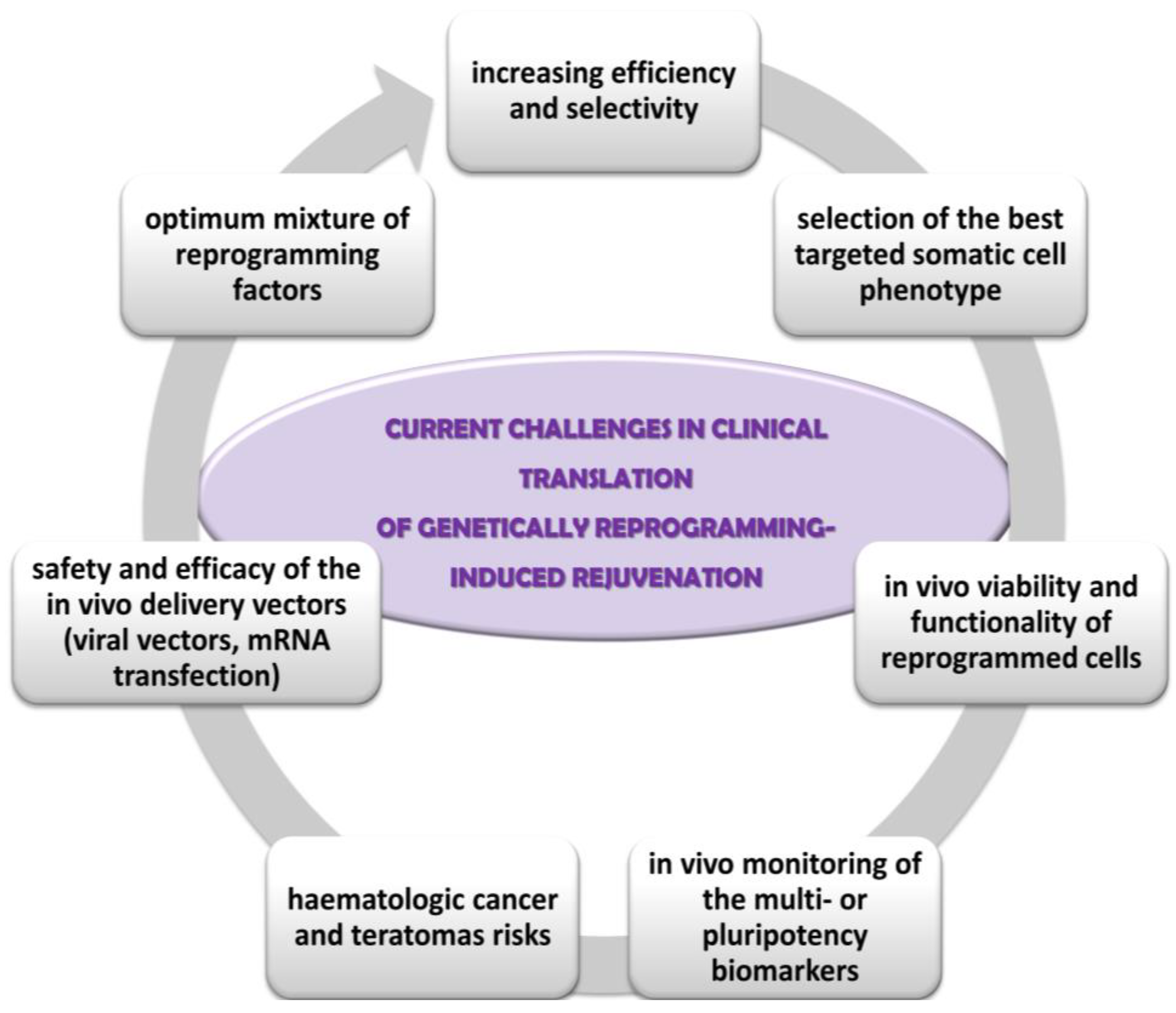

6.2. Genetically Reprogramming-Induced (Skin) Rejuvenation Strategies

- ✓

- the optimum mixture of reprogramming factors for each cell phenotype; low efficiency (about 25% of cells in culture being partially reprogrammed); lack of selective rejuvenation by reprogramming expression of genes which are not essential to ageing; lack of influence on some ageing hallmarks, such as mitochondrial DNA mutations, intracellular and extracellular metabolic aggregates [85,93];

- ✓

- the selection of the somatic cell type targeted for reprogramming; fibroblasts are best candidates due to their proportion in the skin, supportive role, proliferative capacity, the implication of their contractile form (myofibroblasts) in the non-functional persistent scars [51];

- ✓

- integration of the reprogrammed cells into the tissue physiology, especially in age diseases context; the persistence and the degree of the functionality of reprogrammed cells within the in vivo tissue microenvironment [87];

- ✓

- insufficient optimization and monitoring of the reprogramming techniques; for instance, in vivo monitoring of the multi- or pluripotency biomarkers in order to minimize long-term tumorigenesis risk, the stability and viability of the rejuvenated cells in culture and in vivo, the rate of ageing of the younger phenotype cells in comparison with the normal, un-reprogrammed skin cells [91];

- ✓

- carcinogenic risks: activation of oncogenes, point mutations in coding DNA associated with genomic instability and teratomas’ development; phenotypic mosaicism of partially reprogrammed stem cells can cause lineage bias, dysfunctional stem cell and higher haematologic cancer and teratomas risks [86,112];

- ✓

- the safety and efficacy of the in vivo delivery vectors of the reprogramming transcriptional factors. For instance, viral vectors are associated with increased cancer risk because they can cause insertional mutagenesis, residual expression or re-activation of reprogramming factors, or might have broad organ-tropism [84,109,114]. Other safer delivery methods already tested are transient transfection with non-integrating viral vectors, mRNA transfection, or chemically induced reprogramming by small molecules and growth factors.

6.3. Chemically Reprogramming-Induced Skin Rejuvenation Strategies

6.3.1. Small-Molecule Epigenetic Drugs: Main Inhibitors of HDAC and DNMT, and Activators of Sirtuin SIRT6

6.3.2. MicroRNAs (miRNAs)-Based Modulators in Skin Rejuvenation

- ✓

- miR-29 family (miR-29a, miR-29b, miR-29c), which suppress the expression of MMPs within ECM, thus decreasing collagen degradation and maintaining skin’s collagen levels; they also upregulate the expression of collagen genes (COL1A1, COL3A1) [132];

- ✓

- miR-146a, that interferes the NF-κB inflammatory pathway by targeting IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6); in mice models with UVB (ultraviolet B)-induced photoageing and inflammation, topical or injected miR-146a has reduced erythema, skin senescence markers and improved skin healing [133];

- ✓

- inhibitors of miR-34a, which up-regulate the expression of the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) gene involved in longevity and DNA repair; in vitro, inhibitors of miR-34a have stimulated proliferation of cultured fibroblasts and have diminished senescence biomarkers [134];

- ✓

- inhibitors of miR-155, which have demonstrated the capacity to reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines and pigmentation associated with chronic inflammation in aged human skin biopsies; inhibitors of miR-155 up-regulate the expression of the suppressor of cytokine signalling SOCS1 gene; SOCS1 protein inhibits the JAK/STAT pathway (Associated Janus Kinases/Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) and therefore it has a crucial role as negative regulator of cytokine signalling in immune disorders, cancer and inflammation [132];

- ✓

- miR-21, that targets inhibitors of skin regeneration and wound healing, such as phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) and sprouty homologue 1 (SPRY1); miR-21 has stimulated fibroblasts’ division, collagen synthesis, keratinocyte migration and dermal matrix restoration, in in vivo murine wounds models [134];

- ✓

- miR-200c, that has reduced the levels of oxidative stress and has regulated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in in vitro studies, due to its capacity to target zinc finger transcription factors (E-box-binding homeobox 1 and 2, ZEB1 and ZEB2) [134].

| miRNA Approach | Regulation of Principal Target Gene(s) | Main Results | Stage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | ↓ PTEN ↓ SPRY1 | ↑ fibroblast proliferation and healing; ↑ collagen synthesis; ↑ keratinocyte migration and dermal matrix restoration | Preclinical, in vivo murine wounds models | [134] |

| topical application of miR-21: improved skin elasticity and moisture; no major adverse effects | early clinical-phase I | [135] | ||

| miR-29a/b/c | ↓ MMPs ↑ COL1A1 | ↓ ECM degradation; ↑ collagen production; ↑ dermal structure; ↓ wrinkles | Preclinical: in vitro/human dermal fibroblasts; animal models | [132] |

| miR-146a | NF-κB inflammatory pathway: ↓ IRAK1 ↓ TRAF6 | topical or injected miR-146a: anti-inflammatory; ↓ UVB damage; ↓ erythema, skin senescence markers; ↑ skin healing | Preclinical: mice models of UVB-induced ageing | [133] |

| topical application of miR-146a-loaded nanoparticles: ↑ skin elasticity and moisture; no major adverse reactions | early clinical—Phase I | [135] | ||

| inhibitors of miR-34a | ↑ SIRT1 gene | ↑ fibroblasts’ proliferation and longevity; ↓ senescence biomarkers | Preclinical: in vitro fibroblasts cultures | [134] |

| inhibitors of miR-155 | ↑ SOCS1 | ↓ chronic inflammation; ↓ inflammatory cytokines; ↓ skin pigmentation | Preclinical: aged human skin samples | [132] |

| miR-200c | zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox ZEB1, ZEB2 | ↓ oxidative stress; ↑ epithelial–mesenchymal transition | Preclinical: in vitro | [94,130,134] |

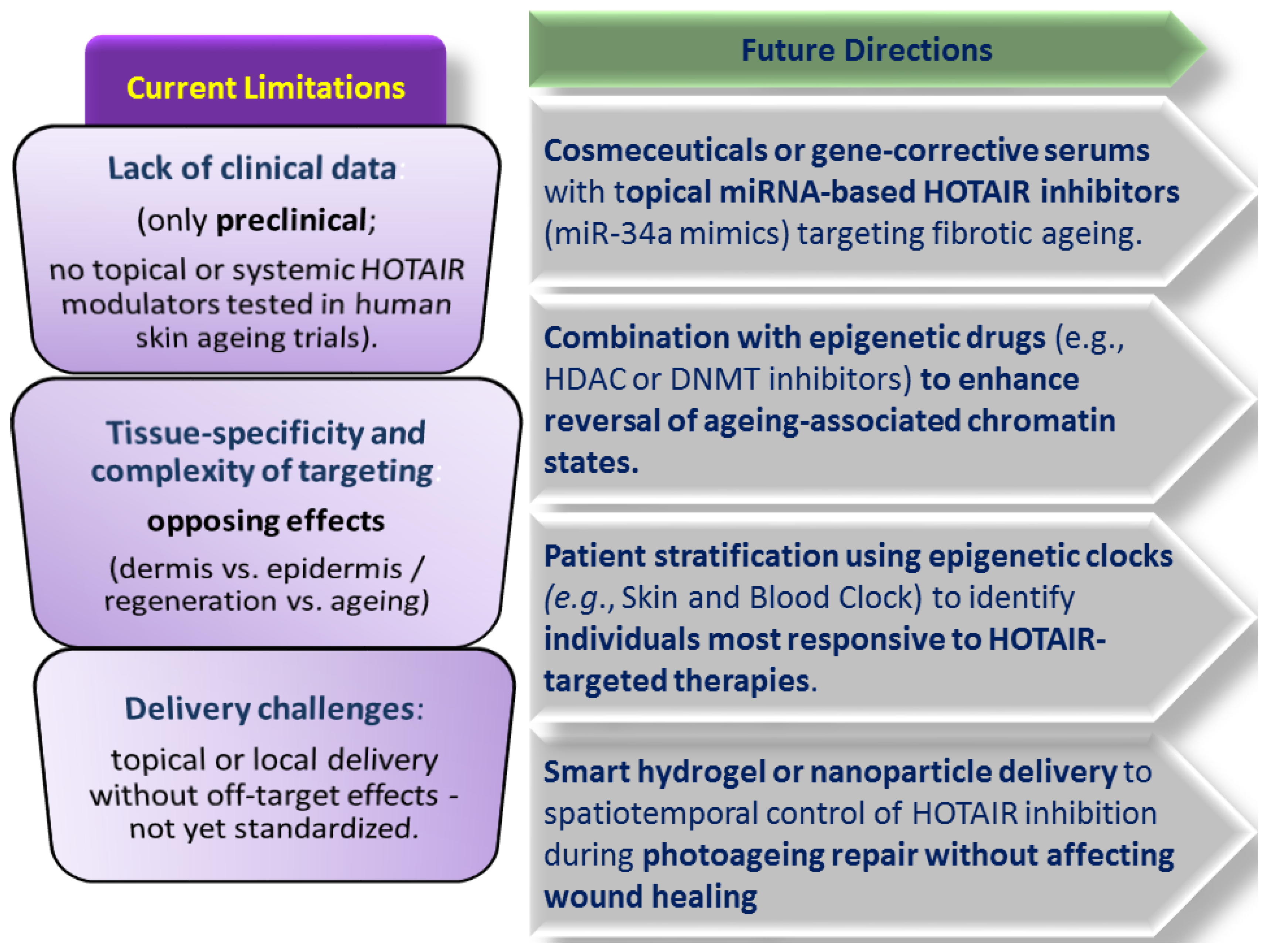

6.3.3. Modulators of the Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR in Skin Rejuvenation

6.3.4. Gene Editing by CRISPR-Based Approaches in Skin Rejuvenation

7. Skin Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Dysregulated Nutrient Sensing Pathways

8. Skin Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction

9. Comparative Analysis of Genomic/Epigenomic-Based vs. Classical Skin Rejuvenation Treatments

10. Other Clinically Tested Anti-Ageing Strategies

10.1. Anti-Ageing Approach of Inflammageing

10.2. Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Altered (Macro)autophagy and Intercellular Communication

10.3. Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Recovery of Skin Proteostasis

10.4. Anti-Ageing Strategies Targeting Skin Dysbiosis

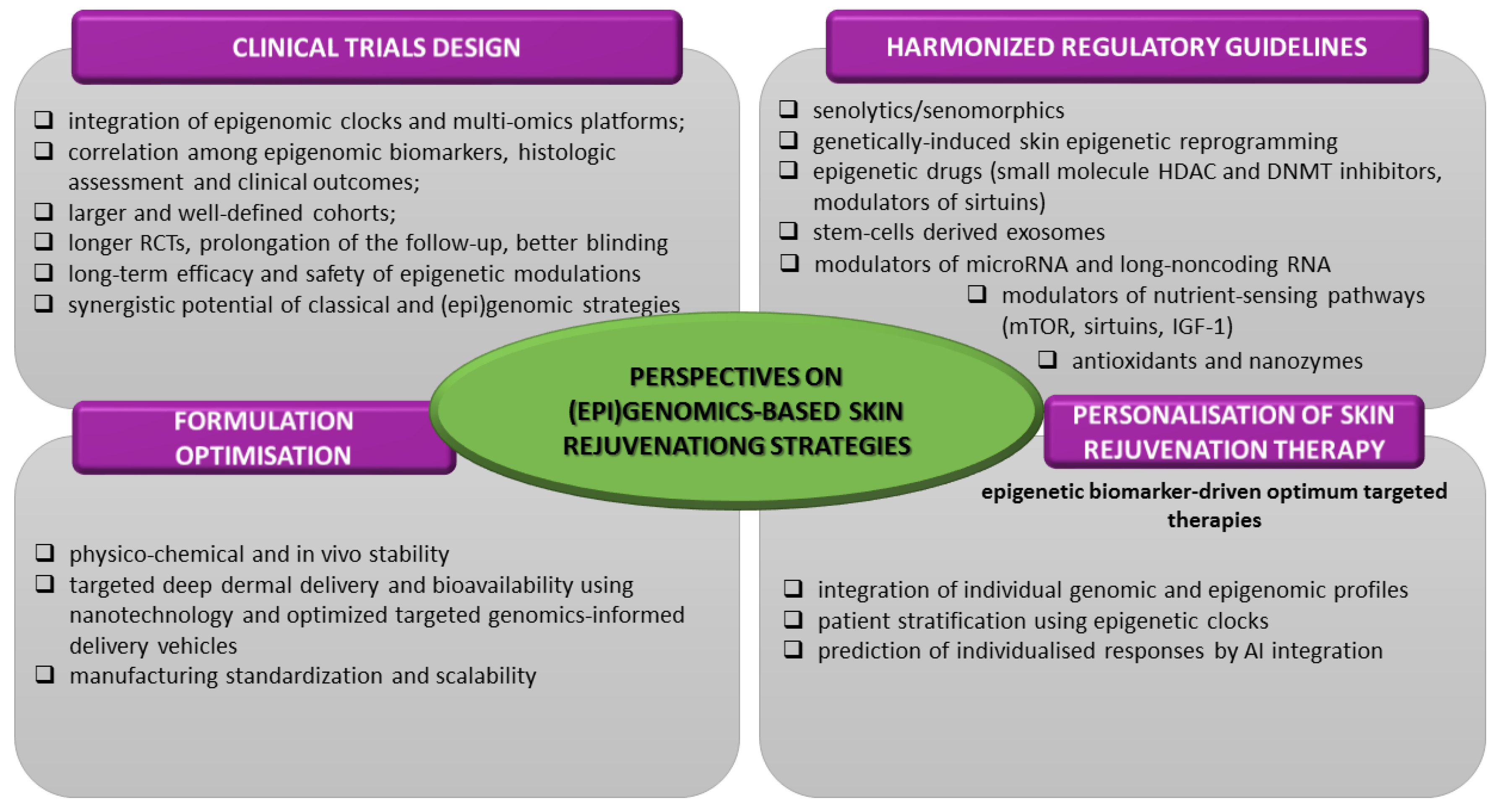

11. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

- ✓

- prioritize the integration of epigenomic clock biomarkers (DNAm, Horvath’s, GrimAge) as well as the multi-omics platforms (epi/genomics-transcriptomics-metabolomics-proteomics) in order to quantitatively assess epigenetic and biological age reversal;

- ✓

- expand the correlation among epigenomic and genomic biomarkers, histologic assessment and clinical outcomes;

- ✓

- elucidate the relationship between the dose and administration period and the (epi)genomic response;

- ✓

- define the long-term safety implications of genomic modulation;

- ✓

- reinforce the clinical validation of efficacy and toxicological profile by enrollment of larger and well-defined cohorts, increase the statistical power (at least over 100 participants), by application of placebo control and blinding (especially with half-face designs) in longer-term RCTs, by prolongation of the follow-up (at least 1 year) period for the evaluation of the desired and unwanted effects’ persistence and possible regression [44,63,118,119,135,136,144,147,155].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Autologous conditioned serum |

| AD-MSCs | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| ADSC-exo | Adipose-derived stem cell exosomes |

| AE | Adverse event |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end products |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AKT | Protein kinase B (involved in survival and growth signalling) |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase (energy-sensing enzyme) |

| AMSCs | amniotic membrane stem cells |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| ATM | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (kinase activated by DNA damage) |

| Bcl-2 | B-Cell lymphoma 2 (anti-apoptotic protein) |

| BCS | Blood cell secretome |

| BET | Bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins |

| circRNA | circular RNAs |

| COL8A1 | collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain |

| CoQ10 | coenzyme Q10 |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CRISPRa | CRISPR activation (gene upregulation method, without altering the DNA sequence) |

| CRISPRd | CRISPR-direct |

| CRP | C reactive protein |

| D + Q | Dasatinib + quercetin (a common senolytic drug combination) |

| DDR | DNA damage repair |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNAm | DNA methylation (age) |

| DNMT1 | DNA methyltransferase 1 |

| DRI | D-Retro-inverso (peptide configuration for therapeutic stability) |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ELN | Elastin |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EPPK | Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma |

| EV | Exosomes/extracellular vesicles |

| EWAS | Epigenome-wide association study |

| 4F | Yamanaka factors or OSKM factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and c-Myc |

| FOXO4 | Forkhead box O4 (transcription factor involved in senescence survival signalling) |

| FOXO4-DRI | FOXO4-D-retro-inverso-isoform peptide |

| GAIS | Global esthetic improvement scale |

| GLS1 | Glutaminase-1 |

| GPNMB | Glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein B (senescence surface marker) |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| HaCaT | Human keratinocyte cell line |

| HACS | Human adipose tissue-derived exosome-containing solution |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HDACi | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| HIF1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (transcription factor in low oxygen) |

| HOTAIR | HOX transcript antisense RNA |

| HPE | Human platelet extract |

| hUC-MSCs | Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| i.v. | Intravenous |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IIS | IGF-1 signalling pathway |

| IKK | IκB Kinase (activates NF-κB) |

| IL-6, IL-8 | Interleukin-6, interleukin-8 (pro-inflammatory cytokines, part of SASP) |

| IPL | Intense pulsed light |

| i-PRF | Injectable platelet-rich fibrin |

| iPSCs | Tissue-induced pluripotent stem cells |

| IRAK1 | Interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinase 1 |

| JAK/STAT pathway | Associated Janus kinases/ Signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| Krt9 | Keratin 9 gene |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNAs |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| MAE | Mean absolute error (related to skin epigenetic clocks) |

| meQTL | Epigenome-wide methylation quantitative loci |

| miRNA | microRNAs |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteases |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin (a central regulator of cell growth and metabolism) |

| NAD | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NBDS | Non-bulbar dermal sheath cells |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (inflammation pathway) |

| OGG1 | 8-Oxoguanine glycosylase photolyase |

| OSKM factors | Yamanaka transcription factors or 4F: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and c-Myc |

| OSKMLN factors | Transcription factors OSKM + LIN28 + NANOG |

| p16Ink4A | Cyclin-dependent kinase Inhibitor 2A (senescence marker) |

| p53-pS15 | p53-Serine15 phosphorylation |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (cell survival signalling pathway) |

| PKR | Protein kinase R |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (nuclear receptor) |

| PRC2 | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 |

| PRF | Platelet-rich fibrin |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and TENsin (tumour suppressor gene) |

| QC | Quality control |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| Ref | Reference |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNase | Ribonuclease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAHF | Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype (pro-inflammatory profile of senescent cells) |

| SAβGal | Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (marker enzyme for senescent cells) |

| shRNA | Short hairpin RNA |

| SIRT | Sirtuin |

| SOCS | Suppressor of cytokine signalling |

| α--SMA | alpha-Smooth muscle actin |

| SPRY1 | Sprouty homologue 1 |

| TCA | Trichloracetic acid |

| TGF | Transforming growth factor |

| TNF | Tumour necrotic factor |

| TRAF6 | TNF receptor associated factor 6 (inflammatory signalling mediator) |

| TRF2 | Telomeric repeat binding factor 2 |

| UVB | Ultraviolet B |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WBC | White blood cells |

References

- Karimi, N. Approaches in line with human physiology to prevent skin aging. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1279371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcknight, G.; Shah, J.; Hargest, R. Physiology of the skin. Surg. Oxf. 2024, 40, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Biological age revisited. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Cohen, H.; Felton, S.; Matsuyama, M.; Lowe, D.; Kabacik, S.; et al. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging 2018, 10, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, D.L.; Belsky, D.W.; Sugden, K.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; Arseneault, L.; Hannon, E.; Mill, J. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife 2022, 11, e73420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorelli, S.; Passos, J.F. Telomeres and cell senescence—Size matters not. EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R.M.; Chen, J.Y.; Raman, C.; Slominski, A.T. Photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology: How the ultraviolet radiation regulates the body, brain, and immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2024, 121, e2308374121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Lee, X.E.; Ng, P.Y.; Lee, Y.; Dreesen, O. The role of cellular senescence in skin aging and age-related skin pathologies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 22, 1297637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Li, K.; Zong, X.; Eun, S.; Morimoto, N.; Guo, S. Hallmarks of Skin Aging: Update. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaggs, H.; Lephart, E.D. Enhancing Skin Anti-Aging through Healthy Lifestyle Factors. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, W.E. Its written all over your face: The molecular and physiological consequences of aging skin. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 190, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.J.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, S.S.; Muther, C.; Tessier, A.; Lee, G.; Gendronneau, G.; Forestier, S.; et al. Senescent melanocytes driven by glycolytic changes are characterized by melanosome transport dysfunction. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3914–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.J.; Navarro, C.; Durán, P.; Galan-Freyle, N.J.; Parra Hernández, L.A.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C.; Castelanich, D.; Bermúdez, V.; Chacin, M. Antioxidants in photoaging: From molecular insights to clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dong, J.; Du, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, P. Collagen study advances for photoaged skin. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2024, 40, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganelli, M.; Stabile, G.; Scharf, C.; Podo Brunetti, A.; Paolino, G.; Giuffrida, R.; Bigotto, G.D.; Damiano, G.; Mercuri, S.R.; Sallustio, F.; et al. Skin Photodamage and Melanomagenesis: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogeska, R.; Mikecin, A.M.; Kaschutnig, L.; Fawaz, M.; Büchler-Schäff, M.; Le, D.; Ganuza, M.; Vollmer, A.; Paffenholz, S.V.; Asada, N.; et al. Inflammatory exposure drives long-lived impairment of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal activity and accelerated aging. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: From molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, G.; Buratta, S.; Pallotta, M.T.; Chiasserini, D.; Di Michele, A.; Emiliani, C.; Giovagnoli, S.; Pascucci, L.; Romani, R.; Bellezza, I.; et al. Extracellular vesicles in aging: An emerging hallmark? Cells 2023, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabibzadeh, S. Cell-centric hypotheses of aging. Front. Biosci. 2021, 26, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, D.; Chen, L.; Kowal, J.M.; Okla, M.; Manikandan, M.; AlShehri, M.; AlMana, Y.; AlObaidan, R.; AlOtaibi, N.; Hamam, R.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits adipocyte differentiation and cellular senescence of human bone marrow stromal stem cells. Bone 2020, 133, 115252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Sanchez, M.; Lancel, S.; Boulanger, E.; Neviere, R. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Treatment of Impaired Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2018, 24, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Xiong, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Hong, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Sun, X. Cellular rejuvenation: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haykal, D.; Flament, F.; Mora, P.; Balooch, G.; Cartier, H. Unlocking Longevity in Aesthetic Dermatology: Epigenetics, Aging, and Personalized Care. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig-Genovés, J.V.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Mena-Mollà, S. A miRNA-based epigenetic molecular clock for biological skin-age prediction. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiganescu, A.; Whitley, A.J.; Reynolds, R.M. Epigenetic skin aging and lifestyle: From mechanisms to intervention. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqri, M.; Chiara, H.; Jesse, R.P.; Justice, J.; Belsky, D.; Higgins-Chen, A.; Moskalev, A.; Fuellen, G.; Cohen, A.A.; Bautmans, I.; et al. Biomarkers of Aging for the Identification and Evaluation of Longevity Interventions. Cell 2023, 186, 3758–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, J.; Oh, H.; Wyss-Coray, T. Measuring biological age using omics data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Deelen, J.; Illario, M.; Adams, J. Challenges in anti-aging medicine-trends in biomarker discovery and therapeutic interventions for a healthy lifespan. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 2643–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Cao, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Aging Biomarker Consortium: Biomarkers of aging. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 893–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Bao, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Molecular mechanisms of aging and anti-aging strategies. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladimir, K.; Perišić, M.M.; Štorga, M.; Mostashari, A.; Khanin, R. Epigenetics insights from perceived facial aging. Clin. Epigenetics 2023, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Li, J.L.; Tong, L.; Jasmine, F.; Kibriya, M.G.; Demanelis, K.; Oliva, M.; Chen, L.S.; Pierce, B.L. DNA methylation correlates of chronological age in diverse human tissue types. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2024, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroni, M.; Zonari, A.; Reis de Oliveira, C.; Alkatib, K.; Ochoa Cruz, E.A.; Brace, L.E.; Lott de Carvalho, J. Highly accurate skin-specific methylome analysis algorithm as a platform to screen and validate therapeutics for healthy aging. Clin. Epigenet 2020, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; Reiner, A.P.; Aviv, A.; Raj, K.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Li, Y.; Stewart, J.D.; et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2019, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondronasiou, D.; Gill, D.; Mosteiro, L.; Urdinguio, R.G.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Aguilera, M.; Durand, S.; Aprahamian, F.; Nirmalathasan, N.; Abad, M.; et al. Multi-omic rejuvenation of naturally aged tissues by a single cycle of transient reprogramming. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetpal, S.; Ghosh, D.; Roostaeian, J. Innovations in Skin and Soft Tissue Aging-A Systematic Literature Review and Market Analysis of Therapeutics and Associated Outcomes. Aesth. Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.D. Aging clocks & mortality timers, methylation, glycomic, telomeric and more. A window to measuring biological age. Aging Med. 2022, 5, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krištić, J.; Lauc, G. The importance of IgG glycosylation-What did we learn after analyzing over 100,000 individuals. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 328, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müezzinler, A.; Zaineddin, A.K.; Brenner, H. Body mass index and leukocyte telomere length in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.X.; Wang, W.J.; Gu, X.P.; Wu, P.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Jiang, D.W.; Huang, J.Q.; Ying, X.W.; et al. Spatiotemporal multi-omics: Exploring molecular landscapes in aging and regenerative medicine. Mil. Med. Res. 2024, 11, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prašnikar, E.; Borišek, J.; Perdih, A. Senescent cells as promising targets to tackle age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 66, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T.; Zhu, Y.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. The clinical potential of senolytic drugs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadecka, A.; Nowak, N.; Bulanda, E.; Janiszewska, D.; Dudkowska, M.; Sikora, E.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A. The senolytic cocktail, dasatinib and quercetin, impacts the chromatin structure of both young and senescent vascular smooth muscle cells. Geroscience 2025, 47, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Carreras-Gallo, N.; Lopez, L.; Turner, L.; Lin, A.; Mendez, T.L.; Went, H.; Tomusiak, A.; Verdin, E.; Corley, M.; et al. Exploring the effects of Dasatinib, Quercetin, and Fisetin on DNA methylation clocks: A longitudinal study on senolytic interventions. Aging 2024, 16, 3088–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J.; Andersen, J.K.; Kapahi, P.; Melov, S. Cellular senescence: A link between aging and age-related diseases. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2023, 1523, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Trapp, A.; Kerepesi, C.; Gladyshev, V.N. Emerging rejuvenation strategies-Reducing the biological age. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Laberge, R.M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Janakiraman, K.; Sharpless, N.E.; Ding, S.; Feng, W.; et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabibzadeh, S. From genoprotection to rejuvenation. Front. Biosci. 2021, 26, 97–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y.Y.; Melos, K.I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, I.; Rallis, C. The target of rapamycin signalling pathway in ageing and lifespan regulation. Genes 2020, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Chung, C.; Lawrence, I.; Hoffman, M.; Elgindi, D.; Nadhan, K.; Potnis, M.; Jin, A.; Sershon, C.; Binnebose, R.; Lorenzini, A.; et al. Topical rapamycin reduces markers of senescence and aging in human skin: An exploratory, prospective, randomized trial. GeroScience 2019, 41, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoretti, P.; Emanuele, E. Clinically Actionable Topical Strategies for Addressing the Hallmarks of Skin Aging: A Primer for Aesthetic Medicine Practitioners. Cureus 2024, 16, 52548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, L.D.; Xu, Z.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Enechojo, O.S.; Abankwah, J.K.; Peng, Y.; Chu, X.; Zhou, H.; et al. Role of epigenetics in the regulation of skin aging and geroprotective intervention: A new sight. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Xie, F.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhong, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, T. Metformin: A Potential Candidate for Targeting Aging Mechanisms. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Montalvo, A.; Mercken, E.M.; Mitchell, S.J.; Palacios, H.H.; Mote, P.L.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Gomes, A.P.; Ward, T.M.; Minor, R.K.; Blouin, M.J.; et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarani, R.; Mohammed, S.; Richardson, A. Effect of rapamycin on aging and age-related diseases-past and future. Geroscience 2021, 43, 1135–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.J.W.; Hodzic Kuerec, A.; Maier, A.B. Targeting ageing with rapamycin and its derivatives in humans: A systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonari, A.; Oliveira, C.R.; Ochoa, E.A.; Carvalho, J.L.; Brace, L.; Boroni, M.; Guiang, M.; Franco, O.; Porto, W.F.; Silva, T.A. Polypeptides Having anti Senescent Effects and Uses Thereof. U.S. Patent 12,268,747, 6 January 2025. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US12268747B2/en (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hu, L.; Mauro, T.M.; Dang, E.; Man, G.; Zhang, J.; Lee, D.; Wang, G.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M.; Man, M.Q. Epidermal Dysfunction Leads to an Age-Associated Increase in Levels of Serum Inflammatory Cytokines. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kumata, K.; Xie, L.; Kurihara, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Kokufuta, T.; Nengaki, N.; Zhang, M.R. The Glutaminase-1 Inhibitor [11C-carbony]BPTES: Synthesis and Positron Emission Tomography Study in Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K.; Ishii, T.; Asou, T.; Kishi, K. Glutaminase inhibitors rejuvenate human skin via clearance of senescent cells: A study using a mouse/human chimeric model. Aging 2022, 14, 8914–8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johmura, Y.; Yamanaka, T.; Omori, S.; Wang, T.W.; Sugiura, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kumamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; et al. Senolysis by glutaminolysis inhibition ameliorates various age-associated disorders. Science 2021, 371, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.X.; Li, Z.S.; Liu, Y.B.; Pan, B.; Fu, X.; Xiao, R.; Yan, L. FOXO4-DRI induces keloid senescent fibroblast apoptosis by promoting nuclear exclusion of upregulated p53-serine 15 phosphorylation. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, B.; Spreitzer, E.; Platero-Rochart, D.; Paar, M.; Zhou, Q.; Usluer, S.; de Keizer, P.L.J.; Burgering, B.M.T.; Sánchez-Murcia, P.A.; Madl, T. The disordered p53 transactivation domain is the target of FOXO4 and the senolytic compound FOXO4-DRI. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Fu, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.D.; He, R.; Zhang, X.; Ju, Z.; Campisi, J.; et al. The flavonoid procyanidin C1 has senotherapeutic activity and increases lifespan in mice. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1706–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.S.; Dreesen, O.; Ryu, J.H. Senolytics for skin aging: Evidence from animal models and potential clinical translation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Li, M.; Xie, P.F.; Si, J.Y.; Feng, Z.J.; Tang, C.F.; Li, J.M. Procyanidin C1 ameliorates aging-related skin fibrosis through targeting EGFR to inhibit TGFβ/SMAD pathway. Phytomedicine 2025, 142, 156787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baar, M.P.; Brandt, R.M.C.; Putavet, D.A.; Klein, J.D.D.; Derks, K.W.J.; Bourgeois, B.R.M.; Stryeck, S.; Rijksen, Y.; van Willigenburg, H.; Feijtel, D.A.; et al. Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell 2017, 169, 132–147.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, R.; Sun, M.; Jia, S.; Liu, J. Cycloastragenol: A Novel Senolytic Agent That Induces Senescent Cell Apoptosis and Restores Physical Function in TBI-Aged Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, S.A.; Darrah, M.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Ciotlos, S.; Rossman, M.J.; Campisi, J.; Seals, D.R.; Melov, S.; Clayton, Z.S. Late Life Supplementation of 25-Hydroxycholesterol Reduces Aortic Stiffness and Cellular Senescence in Mice. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, Q.; Wufuer, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, R.; Jiang, Z.; Dou, X.; Fu, Q.; Campisi, J.; Sun, Y. Rutin is a potent senomorphic agent to target senescent cells and can improve chemotherapeutic efficacy. Aging Cell. 2024, 1, e13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Song, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, D. Dihydromyricetin identified as a natural DNA methylation inhibitor with rejuvenating activity in human skin. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1258184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clariant International Ltd. Compositions Comprising Silybum Marianum Extract as Senotherapeutic Agent. U.S. Patent US20230330003A1, 19 October 2023. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2022073709 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Study of PCC1 and Senolytic Complex (Cellumiva) for Skin Rejuvenation. Clinical Trial NCT06641869; 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06641869?cond=senolytic&viewType=Table&checkSpell=&rank=3 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Manda, G.; Rojo, A.I.; Martinez-Klimova, E.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Cuadrado, A. Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid: From Herbal Medicine to Clinical Development for Cancer and Chronic Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybiak, J.; Broniarek, I.; Kiryczyński, G.; Los, L.D.; Rosik, J.; Machaj, F.; Sławiński, H.; Jankowska, K.; Urasińska, E. Aspirin and its pleiotropic application. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 866, 172762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacitharan, P.K. Senolytic drugs as a novel class of anti-aging agents: Scientific promise, clinical challenges. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13182. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, D.; Wagner, W. Epigenetic rejuvenation by partial reprogramming. Bioessays 2023, 45, e2200208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, A.R.; Larrick, J.W. Epigenetic Age Reversal by Cell-Extrinsic and Cell-Intrinsic Means. Rejuvenation Res. 2019, 22, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Gladyshev, V.N. The meaning of adaptation in aging: Insights from cellular senescence, epigenetic clocks and stem cell alterations. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Lu, Q. The critical importance of epigenetics in autoimmune-related skin diseases. Front. Med. 2024, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkov, A.; Seluanov, A.; Vera, G. Sirtuin 6: Linking Longevity with Genome and Epigenome Stability. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, G.H. Epigenetic regulation of aging: Implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyret, E.; Paloma, M.R.; Aida, P.L.; Juan Carlos, I.B. Elixir of life: Thwarting aging with regenerative reprogramming. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.J.; Olova, N.N.; Chandra, T. Cellular reprogramming and epigenetic rejuvenation. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.; Goodell, M.A.; Rando, T.A. Ageing and rejuvenation of tissue stem cells and their niches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Xu, L.; Brunet, A. Turning back time with emerging rejuvenation strategies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.H.; Kwon, H.H.; Seok, J.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.C.; Shin, E.; Park, K.Y. Efficacy of combined treatment with human adipose tissue stem cell-derived exosome-containing solution and microneedling for facial skin aging: A 12-week prospective, randomized, split-face study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyles, S.; Jankov, L.E.; Copeland, K.; Bucky, L.P.; Paradise, C.; Behfar, A. A Comparative Study of Two Topical Treatments for Photoaging of the Hands. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffer, S.L.; Paradise, C.R.; DeGrazia, E.; Halaas, Y.; Durairaj, K.K.; Somenek, M.; Sivly, A.; Boon, A.J.; Behfar, A.; Wyles, S.P. Efficacy and Tolerability of Topical Platelet Exosomes for Skin Rejuvenation: Six-Week Results. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somenek, M.; Handfield, C.; Behfar, A.; Wyles, S. Effect of Topical Platelet Extract for Post-Procedural Skin Recovery with Fractional Carbon Dioxide Skin Laser Resurfacing. J. Clin. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.S.; Lee, J.; Won, Y.; Duncan, D.I.; Jin, R.C.; Lee, J.; Kwon, H.H.; Park, G.H.; Yang, S.H.; Park, B.C.; et al. Skin brightening efficacy of exosomes derived from human adipose tissue-derived stem/stromal cells: A prospective, split-face, randomized placebo-controlled study. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yue, C. Extracellular vesicle: A magic lamp to treat skin aging, refractory wound, and pigmented dermatosis? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1043320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.H.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.C.; Park, K.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Bae, Y.; Park, G.H. Combination Treatment with Human Adipose Tissue Stem Cell-derived Exosomes and Fractional CO2 Laser for Acne Scars: A 12-week Prospective, Double-blind, Randomized, Split-face Study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.T. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells: A novel agent for skin aging treatment. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2024, 11, 7003–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, B.; Emsieh, S. Effectiveness of Topical Conditioned Medium of Stem Cells in Facial Skin Nonsurgical Resurfacing Modalities for Antiaging: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1239–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Ding, N.; Yao, Z.; Wu, M.; Fu, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells: The wine in Hebe’s hands to treat skin aging. Precis. Clin. Med. 2024, 24, pbae004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A review on exosomes application in clinical trials: Perspective, questions, and challenges. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Gómez, L.J.; Origel-Lucio, S.; Hernández-Hernández, D.A.; Pérez-González, G.L. Use of Exosomes for Cosmetics Applications. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ngo, H.T.T.; Hwang, E.; Wei, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yi, T.H. Conditioned Medium from Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Culture Prevents UVB-Induced Skin Aging in Human Keratinocytes and Dermal Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widgerow, A.D.; Ziegler, M.E.; Garruto, J.A.; Bell, M. Effects of a Topical Anti-aging Formulation on Skin Aging Biomarkers. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2022, 15, E53–E60. [Google Scholar]

- Grether-Beck, S.; Alessandra, M.; Thomas, J.; Petra, G.-R.; Kevin John, M.; Rolf, H.; Jean, K. Autologous Cell Therapy for Aged Human Skin: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase-I Study. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 33, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.E.; Sinclair, D.A. Epigenetic changes during aging and their reprogramming potential. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 54, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.D.; Lee, V.; Ramirez, J.L. Transient epigenetic reprogramming: The future of skin rejuvenation. Dermatol. Surg. 2024, 50, S123–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Brommer, B.; Martel, J.; Tian, X.; Krishnan, A.; Meer, M.; Wang, C.; Vera, D.L.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, D.; et al. Mechanisms, pathways and strategies for rejuvenation through epigenetic reprogramming. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, B.; Correia, F.; Alves, I.; Costa, M.; Gameiro, M.; Martins, A.P.; Saraiva, J.A. Epigenetic reprogramming as a key to reverse ageing and increase longevity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 95, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętara, P.; Marta, D.; Maria, A. Why Is Longevity Still a Scientific Mystery? Sirtuins—Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, A.D.; Gladyshev, V.N. The long and winding road of reprogramming-induced rejuvenation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Lee, D.; Ramirez, J. Epigenetic targets for skin rejuvenation: From small molecules to transcriptional modulators. Clin. Epigenetics 2023, 15, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, P.F.; Rorteau, J.; Lamartine, J. MicroRNAs in the Functional Defects of Skin Aging. In Non-Coding RNAs; IntechOpen OpenAccess: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Mendoza, E.; Karanian, J. Equol improves markers of skin aging via DNA methylation modulation. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S. MicroRNA regulation of skin aging. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naharro-Rodriguez, J.; Bacci, S.; Hernández-Bule, M.L.; Pérez-González, A.; Fernández-Guarino, M. Decoding skin aging: A review of mechanisms, markers, and modern therapies. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Beltrán, P.; Herráiz-Gil, S.; Martínez-Moreno, D.; Medraño-Fernande, I.; León, C.; Guerrero-Aspizua, S. Regenerative Cosmetics: Skin Tissue Engineering for Anti-Aging, Repair, and Hair Restoration. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Mercken, E.; Palacios, H.; Ward, T.M.; Abulwerdi, G.; Minor, R.K.; Vlasuk, G.P.; Ellis, J.L.; Sinclair, D.A.; et al. The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 extends lifespan and improves health of mice fed a standard diet. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, B.P.; Sinclair, D.A. Small molecule SIRT1 activators for the treatment of aging and age-related diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, J.M.; Shah, A.; Eichstadt, S.; Bailey, I.; Aasi, S.Z.; Sarin, K.Y. Treatment of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma With the Topical Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Remetinostat. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, J.M.; Shah, A.; Urman, N.M.; Eichstadt, S.; Do, H.N.; Bailey, I.; Mirza, A.; Li, S.; Oro, A.E.; Aasi, S.Z.; et al. Phase II open-label, single-arm trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of topical remetinostat gel in patients with basal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4717–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.; Guilcher, G.M.T.; Greenway, S.C. Reviewing the impact of hydroxyurea on DNA methylation and its potential clinical implications in sickle cell disease. Eur. J. Haematol. 2024, 113, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.R.; Chen, X.L.; Tang, Y.X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Gao, X.; Ke, H.P.; Lin, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.N. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated treatment ameliorates the phenotype of the epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma-like mouse. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harley, C.B.; Liu, W.; Blasco, M.; Vera, E.; Andrews, W.H.; Briggs, L.A.; Raffaele, J.M. A natural product telomerase activator as part of a health maintenance program. Rejuvenation Res. 2011, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, L.; Wu, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Kang, T.; Tao, M.; et al. Disrupting the interaction of BRD4 with acetylated histones inhibits BET bromodomain function. Cell 2014, 149, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. LncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks in skin aging and therapeutic potentials. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1303151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, W.; Yang, Y.; Feng, B.; Xu, Z. Exosomal microRNA-Based therapies for skin diseases. Regen. Ther. 2024, 25, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, M.; Uitto, J. MicroRNA and extracellular matrix interactions in skin aging. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 478–486. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wang, A. miR-146a alleviates UVB-induced skin photoaging by targeting inflammation-related pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K.O.; Kim, M.; Park, K. Role of microRNAs in skin aging and related diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5121. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, C.; Keller, A.; Meese, E. Emerging concepts of miRNA therapeutics: From cells to clinic. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Zhang, Y. Exosomal microRNAs in skin regeneration and rejuvenation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 548. [Google Scholar]

- Wasson, C.W.; Abignano, G.; Hermes, H.; Malaab, M.; Ross, R.L.; Jimenez, S.A.; Chang, H.Y.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A.; Del Galdo, F. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR drives EZH2-dependent myofibroblast activation in systemic sclerosis through miRNA 34a-dependent activation of NOTCH. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, T.; Nagano, H.; Nomura, K.; Hiramatsu, M.; Motoi, N.; Mun, M.; Ishikawa, Y. The combined use of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR and polycomb group protein EZH2 as a prognostic marker of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2022, 31, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romashin, D.D.; Tolstova, T.V.; Rusanov, A.L.; Luzgina, N.G. Non-Coding RNAs and Their Role in Maintaining Epidermal Homeostasis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Yu, W.; Sun, H.; Duan, M.; Lin, X.; Liang, P. Down-regulation of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR promotes angiogenesis via regulating miR-126/SCEL pathways in burn wound healing. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Babakhanzadeh, E.; Mollazadeh, A.; Ahmadzade, M.; Soleimani, E.M.; Hajimaqsoudi, E. HOTAIR in cancer: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic perspectives. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Shao, M.; Su, W.; Song, N. Curcumin Regulates Cancer Progression: Focus on ncRNAs and Molecular Signaling Pathways. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 660712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Chan, I.L.; Cao, Y.; Gruntman, A.L.; Lee, J.; Sousa, J.; Rodríguez, T.C.; Echeverria, D.; Devi, G.; Debacker, A.J.; et al. Intratracheally administered LNA gapmer antisense oligonucleotides induce robust gene silencing in mouse lung fibroblasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 8418–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ji, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Guillen-Garcia, P.; Esteban, C.R.; Reddy, P.; Horvath, S.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR activation screening in senescent cells reveals SOX5 as a driver and therapeutic target of rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Wu, W.; Peng, S.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; Yang, B.; Jia, F.; Lu, A.; Lu, C.; et al. Microneedle Technology for Overcoming Biological Barriers: Advancing Biomacromolecular Delivery and Therapeutic Applications in Major Diseases. Research 2025, 8, 0879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lu, Z.; Wu, W.; Qian, N.; Wang, F.; Chen, T. Optogenetic gene editing in regional skin. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Age reprogramming: Innovations and ethical considerations for prolonged longevity. Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toniolo, L.; Sirago, G.; Giacomello, E. Experimental models for ageing research. Histol. Histopathol. 2023, 38, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaito, A.; Posadino, A.M.; Younes, N.; Hasan, H.; Halabi, S.; Alhababi, D.; Al-Mohannadi, A.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Eid, A.H.; Nasrallah, G.K.; et al. Potential adverse effects of resveratrol: A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarelli, N.; Gahoonia, N.; Aflatooni, S.; Bhatia, S.; Sivamani, R.K. Dermatologic Manifestations of Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, D. Proteostasis Dysfunction in Aged Mammalian Cells. The Stressful Role of Inflammation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 17, 658742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgzadeh, A.; Paria, A.A.; Saman, Y.; Basim, K.N.; Khairia, A.A. The Potential Use of Nanozyme in Aging and Age-related Diseases. Biogerontology 2024, 25, 583–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Shi, Z.; Su, W.; Wu, J. State of the art and applications in nanostructured biocatalysis. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Rodríguez, A.M.; Martínez-Zamudio, L.Y.; Martínez, S.A.H.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.A.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Flores-Contreras, E.A.; González-González, R.B.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Nanomaterial Constructs for Catalytic Applications in Biomedicine: Nanobiocatalysts and Nanozymes. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. Targeting Cellular Senescence with Senotherapeutics: Development of New Approaches for Skin Care. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 12S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haykal, D.; Cartier, H.; Goldberg, D.; Michael Gold, M. Advancements in laser technologies for skin rejuvenation: A comprehensive review of efficacy and safety. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3078–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitohang, I.M.S.; Makes, W.I.; Sandora, N.; Suryanegara, J. Topical tretinoin for treating photoaging: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2022, 8, e003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.A. Intense pulsed light therapy for skin rejuvenation. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2006, 25, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarosh, D.B.; Klein, J.; O’Connor, A.; Hawk, J.L. DNA repair enzymes in skin care products: Mechanisms and clinical evidence. Dermatol. Clin. 2005, 23, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, H.J. Chemical peels for skin rejuvenation: An update. Dermatol. Surg. 2016, 42, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, J.D.; Carruthers, A. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of glabellar frown lines. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.A.; Alonso, J.M.; Pérez-González, R.; Velasco, D.; Suárez-Cabrera, L.; de Aranda-Izuzquiza, G.; Sáez-Martínez, V.; Hernández, R. Injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels via Michael addition as dermal fillers for skin regeneration applications. Biomater Adv. 2025, 177, 214364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Duc Tri Luong, D.T.; Thuy-Tien Ho, T.T.; Nguyen Thi, T.M.; Singh, V.; Chu, D.T. Drug repurposing for regenerative medicine and cosmetics: Scientific, technological and economic issues. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 207, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Shastri, M.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, K.; Sharma, A.; Walker Minz, R.; Dogra, S.; Chhabra, S. Cutaneous-immuno-neuro-endocrine (CINE) system: A complex enterprise transforming skin into a super organ. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Caruso, C.; Galimberti, D.; Candore, G. Senotherapeutics to Counteract Senescent Cells Are Prominent Topics in the Context of Anti-Ageing Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonari, A.; Brace, L.E.; Al-Katib, K.; Porto, W.F.; Foyt, D.; Guiang, M.; Ochoa Cruz, E.A.; Marshall, B.; Gentz, M.; Rapozo Guimarães, G.; et al. Senotherapeutic peptide treatment reduces biological age and senescence burden in human skin models. Aging 2023, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baveloni, F.G.; Riccio, B.V.F.; Di Filippo, L.D.; Fernandes, M.A.; Meneguin, A.B.; Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-based Drug Delivery Systems as Potential for Skin Application: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 3216–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitali, A.; Singh, M.K.; Mishra, A.K. Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Combating Skin Aging: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Aging Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, A.A. Trials and Tribulations of MicroRNA Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.Y.; Kee, L.T.; Al-Masawa, M.E.; Lee, Q.H.; Subramaniam, T.; Kok, D.; Ng, M.H.; Law, J.X. Scalable Production of Extracellular Vesicles and Its Therapeutic Values: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Shu, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhang, Y. Advancements in extracellular vesicles biomanufacturing: A comprehensive overview of large-scale production and clinical research. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1487627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Rai, D. Global requirements for manufacturing and validation of clinical grade extracellular vesicles. J. Liq. Biopsy 2024, 6, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Ageing | Definition | Limitations | Reference (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic (chronologic/calendar) (skin) age | Genetically programmed, time-dependent skin changes seen without external damage. | Lacks measureable molecular markers; occurs slowly. | [3] |

| Biological (phenotypic) age | Reflects how well a person’s body (or skin) is functioning relative to peers, using functional or molecular data. | Requires biomarker panels; may lack tissue specificity. | |

| Epigenetic age (DNAm age, CpG clock) | Age estimated from deoxyribonucleic acid DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns at CpG sites, correlates with cellular ageing. | Needs lab-based testing; clocks vary in accuracy and clonal specificity. | [4,5] |

| Skin age (dermal age) | Biological or epigenetic age of skin tissue specifically, often with skin-optimized clocks. | Dependent on validated skin-specific models; requires biopsies or swabs. | [6] |

| Photoageing (UV-ageing, photodamage) | Premature ageing of skin caused by chronic ultraviolet exposure. | Primarily assessed clinically or histologically, not quantified by molecular clocks. | [3,7] |

| Pace of ageing (ageing rate, velocity) | Rate at which biological ageing progresses over time, often via longitudinal DNAm measures. | Not absolute age; indirect for skin unless validated in skin tissues. | [7] |

| Senescence (cellular ageing markers) | State of irreversible cell-cycle arrest, often with Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) and markers like p16INK4A. | Requires invasive sampling and is qualitative rather than quantitative. | [8] |

| Inflammageing (age-related inflammation) | Chronic low-grade systemic or skin inflammation marked by cytokines (e.g., interleukin IL-6, C reactive protein CRP, tumour necrotic factor TNF-α). | Non-specific; fluctuates with environmental or health variables. | [9] |

| Feature | Chronologically Aged Skin | Photoaged Skin | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic pathways | Progressive mitochondrial decline, oxidative stress, modest MMP activity | UV-induced oxidative stress → MAPK/AP-1 and NF-κB pathways’ activation, MMP upregulation, transforming growth factor TGF-β suppression | [15,16,17] |

| Clinical signs | Fine lines, thinning, dryness, reduced elasticity, generally even skin tone | Deep wrinkles, rough texture, pigment spots, telangiectasias, laxity | |

| Histological changes | Thinned epidermis and dermis, decreased fibroblasts | Epidermal hyperplasia, solar elastosis, collagen fragmentation, vascular dilation | |

| ECM, collagen and elastin modifications | Slow ECM degradation via baseline MMP; gradual loss of dermal collagen; mild elastin fibre disorganization developing with age | Rapid collagen breakdown by UV-induced MMP-1/-3/-9; suppressed collagen synthesis; sever elastin fibre disorganization | |

| Inflammation | Low-grade systemic inflammageing | Chronic localized inflammation: elevated IL-6, TNF-α, ROS in photoexposed skin | |

| DNA damage and Senescence | Gradual telomere shortening, modest senescence | UV-triggered DNA mutations (e.g., p53), telomere attrition, accelerated senescence | |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Progressive oxidative damage derived from cells’ metabolism | Acute UV-induced mitochondrial injury causing ROS burst and oxidative stress |

| Clock | Mechanism | Clinical Advantages (Skin and Regenerative Medicine) | Clinical Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIGENETIC CLOCKS | ||||

| Horvath clock (1st generation) | DNAm at 353 CpGs across tissues | Universal tissue clock; baseline age marker for cell-based therapies | Not skin-optimized; slow responsiveness to short-term interventions | [4] |

| Horvath Skin and Blood clock (2nd generation) | DNAm at 391 CpGs (skin/fibroblast-derived) | Highly accurate for skin ageing; ideal for assessing rejuvenating interventions | Requires full methylome data; limited systemic insights | [6] |

| GrimAge (2nd generation) | DNAm proxies for plasma proteins and smoking | Robust mortality predictor; sensitive to systemic drugs (e.g., metformin) | Not specific to skin; limited in localized skin interventions | [37] |

| PhenoAge (2nd generation) | blood DNA methylation patterns linked to clinical ageing-related biomarkers (e.g., CRP, albumin, white blood cells WBC, glucose) | Well validated in predicting: biological age, systemic ageing, mortality risk, and chronic disease prediction; accessible in blood-based anti-ageing research. | Not designed or validated on skin tissue; inaccurate for skin ageing assessment | [5] |

| DunedinPACE (3rd generation) | DNAm-based rate-of-ageing (longitudinal) | Measures short-term ageing pace; suitable for anti-ageing trials | Trained on blood; indirect for skin anti-ageing interventions | [7] |

| miRNA Skin clock (3rd generation) | Skin-specific miRNA transcriptomics | Non-invasive; emerging tool for cosmetic/pharma intervention studies | Not fully validated; lower accuracy (MAE ~8–10.9 years) | [27] |

| Rayan Skin Clock | Tissue-specific epigenetic clock trained on human facial epidermal and dermal fibroblast methylation data, spanning ages 18–90. | Highly accurate and specifically optimized for skin ageing, especially for facial skin; sensitive to esthetic anti-ageing treatments; enables objective and accurate quantification of skin biological age changes after esthetic procedures (like laser resurfacing); detects reversible reprogramming signatures unique to skin; superior to general clocks (e.g., Horvath, PhenoAge) for skin applications. | Requires skin biopsy or high-quality epidermal samples; not yet commercially available for clinical use (mainly applied in research settings); complex methylation analysis pipeline; not validated for darker skin tones or other body areas | [26] |

| NON-EPIGENETIC CLOCKS/MARKERS | ||||

| Telomeres’ length | Telomeric DNA attrition | Historically used; available assays | Poor specificity for skin ageing; weak intervention tracking | [42] |

| Senescence biomarkers | p16INK4A, SAβGAL, SASP cytokines | Mechanistic; reflects rejuvenation via senolytics, retinoids, etc. | Requires tissue samples; not systemically quantifiable | [8] |

| Inflammatory biomarkers | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP (inflammageing) | Reflects chronic skin inflammation; useful in photodamage assessment | Non-specific; transient variations; overlaps with immune response | [9] |

| Knowledge Gaps | Future Research Directions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

Safety and off-target effects

| Long-term safety evaluation

| [10,12,19,44,50,51,59,82,83] |

Formulation

| Transdermal targeted delivery

| |

| Translation from lab to human Most senotherapeutics evaluated in murine models or ex vivo human skin, which cannot fully replicate the complexity of human skin ageing and interindividual variability. Ongoing and closed clinical trials—limited enrolment and diversity: most trials n = 22–74 healthy middle-aged women. | Clinical trials on long-term safety and efficacy Clinical trials design:

| |

| Individualisation of the antiageing senotherapeutics still greatly unaddressed | Biomarker-driven personalization

| |

| Combination approaches currently, few tested | Synergistic combinations

|

| Approach | Trial Design | Main Outcomes | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem-cell EV + microneedling | 12-week prospective randomized split-face RCT (n = 28 women aged 43–66), 3 sessions over 12 weeks: Arm 1 = 12.5% ADSC-derived EV + microneedling vs Arm 2 = saline + microneedling | Significant improvement on treated side vs. control of wrinkles, elasticity, hydration, pigmentation; higher Global esthetic improvement scale (GAIS) scores on treated side vs. control ↑ collagen histologically; transient erythema/petechiae; no serious adverse effects (AEs) | Small cohort; short follow-up; split-face design (within-subject placebo); possible crossover effects; lack of proper placebo | [94,105] |

| Stem-cell EV + fractional CO2 laser: acne scars | 12 weeks, RCT (n = 25): acne scars; Adipose-derived stem cell exosomes (ADSC-exo) + laser vs. laser + control gel | Greater acne-scarring improvement; milder erythema and shorter downtime vs. control gel | Small size; scar-focused; short follow-up; limited generalizability | [97,100] |

| Umbilical cord stem cell- and adipose-derived stem cell-conditioned medium and exosomes, via topical or microneedling | n ≈ 22–30 participants aged 18–69 years; 3–10 weeks, often adjunct to laser or microneedling | Anti-photoageing effects, modulating signalling pathways involved in skin damage and promoting collagen synthesis; ↑ dermal density, ↑ collagen/elastin genes’ expression; improved wrinkles, hydration, pigmentation; minimal side effects | The adjunctive therapies make hard to isolate effects; short follow-up; small sample sizes | [105,106,108] |

| Topical stem-cell conditioned medium + laser resurfacing | Meta-analysis of 5 RCTs | Significant reduction in wrinkles, pigmentation, pore size; improved overall skin condition | Heterogeneity; varied protocols; multiple small RCTs | [102,105] |

| Topical ADSC-exosomes for brightening | 8 week double-blind RCT (n = 21 women): topical ADSC-EV vs. placebo; split-face | Significant melanin reduction at 4 weeks; effect sustained up to 8 weeks; no AEs | Small size samples; limited topical penetration; modest clinical brightness effect | [98,105,107] |

| MSC-derived exosomes ointment | 6 weeks, n = 56 healthy adults, 40–85 years; topical 3D imaging study; split-face histopathologic evaluation | Histopathologic evaluation: ↓ wrinkles, redness, melanin; ↑ luminosity, even tone; safe and well tolerated | Single-arm, no control; non-randomized; short duration; moderate sample size | [95,96,101,103] |

| ADSC-EV injection | Preclinical: UVB-rat photoaged skin | ↓ Epidermal thickening; ↑ dermal thickness; ↑ collagen I; ↓ collagen III; ↓ MMP-1/3 expression | No clinical data; single dose | [105] |

| Exosome skincare + defensins serum | Multi-centre double-blind vehicle-controlled RCT of defensin-containing regimen | Demonstrates clinical and histopathologic benefit | Limited detailed evaluation | [104] |

| Exosomes from genetically engineered stem cells | Phase I/II clinical trials for skin rejuvenation | Delivery of growth factors, miRNAs, epigenetic modulators; skin texture improvement; increased collagen synthesis | Manufacturing standardization; scalability | [94] |

| Human platelet extract (HPE) exosome product | 60 participants (40–80 years), dorsum of hands; 56 participants facial, with 20 biopsies | HPE matched vitamin C in improving texture/tone; well tolerated; ↑ collagen and elastin histologically | Small biopsy sub-cohort; unclear skin-type distribution; no long-term follow-up | [95] |

| MSC growth factor serums | Split-face RCT, 3 months; compare MSC’s growth factor serums vs fibroblast’s growth factor serums; 20 participants with moderate–severe photodamage | Both serums significantly improved wrinkles without difference; well tolerated | Small sample size; unclear penetrance mechanisms; half-face design may confuse effects | [99,101] |

| Intradermal cell therapy: RCS-01 Skin Rejuvenation RepliCel | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase I clinical trial (completed). safety-focused Phase I; small cohort; intradermal injection of collagen-expressing hair-follicle fibroblasts | Non-bulbar dermal sheath (NBDS) cells are prolific producers of tissue building proteins especially type I collagen (5× that of dermal fibroblasts). NDBS cells have been shown to promote in vivo tissue collagen and ECM regeneration; up to 2× increase in gene expression of collagen-related biomarkers; healthier, younger-looking skin after a single injection; no serious AE | Small cohort; not powered for efficacy; only surrogate biomarkers of gene-expression | [108] |

| Small Molecule Epigenetic Agents | Study Design | Main Outcomes | Limitations/Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors: topical remetinostat | Phase II open-label, single-arm clinical trial: topical remetinostat gel in skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma) | Complete clinical and pathological resolution of tumours; epigenetic modulation of skin cells; good dermal penetration; potential for skin anti-ageing use | Cancer context, no direct anti-ageing endpoints; small cohort; off-target effects possible | [120,123,124] |

| Topical sirtuin activators (e.g., resveratrol) | Clinical cosmetic studies; some early-phase trials ongoing | Improved skin hydration, elasticity and antioxidant activity | Mostly cosmetic; small samples size; limited direct epigenetic biomarker data; poor bioavailability | [45,109,114,125] |

| Topical DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors | Early preclinical stages | Potential reversal of aberrant methylation in aged skin | Lack of clinical trials; unclear safety in humans | [105] |

| Restorative Skin complex [RSC] and TriHex™ RSC + Tripeptide-1 + Hexapeptide-12 (Alastin Skin Care/Galderma company) | 22 subjects, 12 week facial applications | Proof of efficacy on in vitro fibroblast and keratinocyte; significant upregulation of the Klotho gene and related FGF23, FGFR1 and FOXO3B longevity genes; significant telomere stabilization by shortening reduction over control (for RSC at 4weeks and for TriHex™ at 6 weeks); positive ECM activation: stimulation of collagen, fibrillin, CD44 and elastin | Relatively small cohort; non-competitive design; limited validation of in vivo mechanism | [107] |

| Hydroxyurea (epigenetic modulator) | Phase I/II trials in photoaged skin | Improved skin texture and reduced pigmentation | Cytotoxicity risks; precise mechanisms in ageing unclear | [119,126] |

| Modulators of ECM synthesis targeting TGF-β signalling | Clinical trials for skin fibrosis and ageing-related skin laxity | Increased collagen; improved skin firmness | Side effects in systemic application | [127] |

| Telomerase activators (e.g., TA-65) | Small-scale human trials; cosmetic application | Potential anti-ageing effects via telomere elongation | Safety concerns; limited large-scale studies | [120,128] |

| BET (Bromodomain and extra-terminal domain proteins) inhibitor (e.g., JQ1) | Preclinical phase only | Modulator of gene transcription by disrupting the interaction of BRD4 with acetylated histones | Potential toxicity; no clinical data | [119,129] |

| Type of HOTAIR’s Modulators | Examples and Mechanism of Action on HOTAIR | Main Preclinical Results | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA mimic | miR-34a mimic inhibits HOTAIR; ↓ GLI2 * via Notch signalling → ↓ fibrotic gene expression | ↓ α-SMA *; ↓ type I collagen; ↓ COL1A1; ↓ fibroblast proliferation and migration in systemic sclerosis dermal fibroblasts | Only in vitro, on disease-specific model from systemic sclerosis rather than on photoaged or normal skin | [137] |

| miR-141, miR-203: direct binding to HOTAIR RNA and post-transcriptional repression | ||||

| HOTAIR- siRNA knockdown | direct silencing of HOTAIR in HaCaT human keratinocytes line; ↓ PKR → ↓ NF-κB and PI3K/AKT pathways’ activation | In cell-targeted treatments, anti-photo-ageing effects: ↓ UVB-induced apoptosis; ↓ IL-6, TNF-α cytokine release; improved keratinocyte survival | Immortalized cell line only (only epidermal model); lacks fibroblast or in vivo support | [139,141] |

| HOTAIR- short hairpin RNA (shRNA **) knockdown | In vivo HOTAIR knockdown: → ↑ miR-126 → activates Wnt/VEGF signalling pathway | Accelerated angiogenesis; faster wound healing in mice burn model | Context-dependent: inhibition may impair regeneration in normal skin | [140] |

| Natural compound regulators | Genistein, EGCG (green tea polyphenol): modulate lncRNA networks and epigenetic enzymes; Curcumin suppresses HOTAIR expression indirectly via epigenetic remodelling | HOTAIR downregulation shown in cancer models; potential extrapolation for reducing inflammatory lncRNA expression in skin ageing | Not tested in skin models directly; unclear bioavailability in topical delivery | [142] |

| Epigenetic drugs (indirect) | HDAC or DNMT inhibitors (e.g., resveratrol, curcumin) inhibit HOTAIR expression; GSK126, an EZH2 inhibitor, blocks HOTAIR binding partner PRC2 → epigenetic reactivation of suppressed anti-ageing genes | Reduced fibrotic gene expression in other models; potential to reverse HOTAIR-EZH2 repression in aged skin | No direct skin ageing studies; possible off-target effects | [138] |

| Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs ***) | LNA-GapmeRs, siRNAs ****: RNA degradation or inhibition of lncRNA–protein interaction | Functional knockdown; studies in other ageing contexts | No direct skin ageing studies | [143] |

| CRISPRd/Cas9 tools | Block HOTAIR promoter activity | Transcriptional silencing; studies focus on other tissues | No evidence yet on skin ageing models | [130] |

| Gene Editing/CRISPR-Assisted Interventions | Study Design | Main Outcomes | Limitations/Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|