Preparation and Antitumor Evaluation of Four Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and 10-Hydroxycamptothecin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Molecular Docking of Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

2.3. Preparation of Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

2.4. Pharmaceutics Evaluation

2.4.1. Appearance, Particle Size and Zeta Potential

2.4.2. Stability of Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

2.4.3. Surface Morphology

2.4.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetric Analysis

2.4.5. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

2.5. Antitumor Effects In Vitro

2.5.1. Cell Culture

2.5.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

2.5.3. Cell Uptake

2.6. In Vivo Antitumor Effects

2.6.1. Cell Culture for Tumor Model

2.6.2. Animal Model and Treatment

2.6.3. Changes in Body Weight

2.6.4. Tumor Growth

2.6.5. Immunohistochemistry

2.6.6. Organ Coefficients

2.6.7. Histopathological Analysis

2.6.8. Serum Biochemistry

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Docking

3.2. Characterization

3.2.1. Appearance

3.2.2. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

3.2.3. Stability

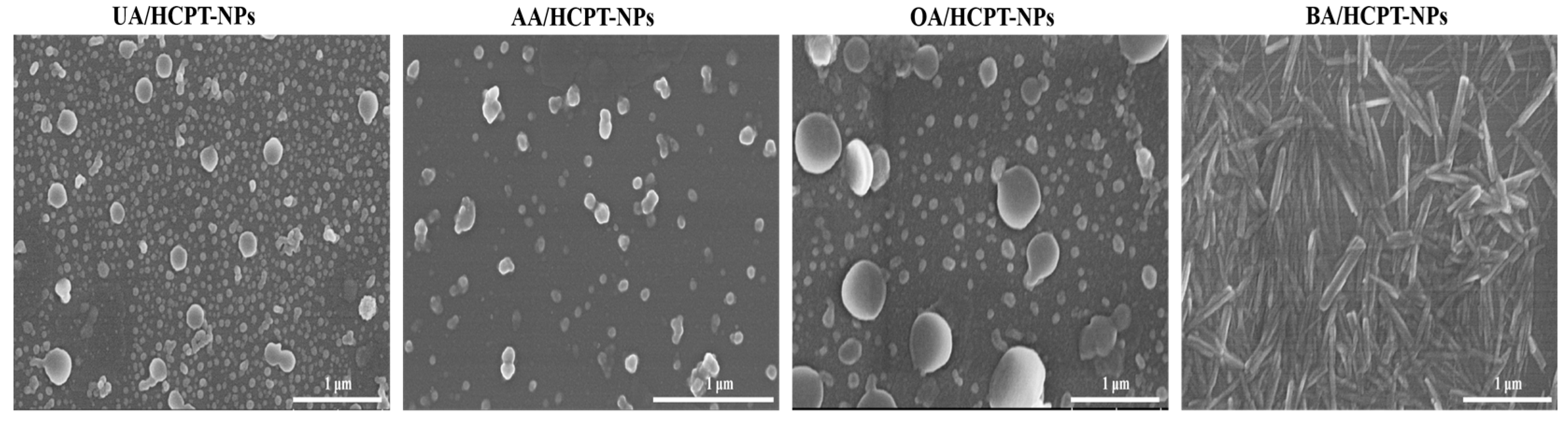

3.2.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

3.2.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

3.3. In Vitro Antitumor Effects

3.3.1. Self-Assembled Nanoparticles Enhance Antitumor Efficacy

3.3.2. Enhanced Cellular Uptake of Self-Assembled Nanoparticles

3.4. Pharmacodynamic Evaluation

3.4.1. Liver Cancer of Animal Model

3.4.2. Body Weight Changes

3.4.3. Tumor Growth Inhibition

3.4.4. Suppression of Tumor Cell Proliferation

3.4.5. Safety Evaluation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCPT | 10-hydroxycamptothecin |

| UA | Ursolic acid |

| AA | Asiatic acid |

| OA | Oleanic acid |

| BA | Betulinic acid |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| APIs | Active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| P188 | Poloxamer 188 |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| PDI | Polymer dispersity index |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| DiI | 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate |

| IRBW | Inhibition rate of body weight |

| TWIR | Tumor weight inhibition rate |

| TGI | Tumor growth inhibition |

| Cre | Creatinine |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

Appendix A

| UA | HCPT | UA + HCPT Mixture | UA/HCPT-NPs | Title 1 | Title 2 | Title 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A375 | 0.104 | 0.305 | 0.2363 | 4.538 × 10−10 | entry 1 | data | data |

| AGS | 115.100 | 1.923 | 0.450 | 0.116 | entry 2 | data | data |

| HCT-116 | 50.280 | 0.699 | 0.164 | 4.848 × 10−12 | |||

| HepG2 | 163.000 | 0.214 | 0.071 | 8.043 × 10−16 |

| AA | HCPT | AA + HCPT Mixture | AA/HCPT-NPs | UA | HCPT | UA + HCPT Mixture | UA/HCPT-NPs | Title 1 | Title 2 | Title 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A375 | 1795 | 0.3050 | 0.1848 | 4.954 × 10−9 | A375 | 0.104 | 0.305 | 0.2363 | 4.538 × 10−10 | entry 1 | data | data |

| AGS | 9.184 | 1.923 | 0.6872 | 0.2491 | AGS | 115.100 | 1.923 | 0.450 | 0.116 | entry 2 | data | data |

| HCT-116 | 98.60 | 0.6992 | 2.303× 10−5 | 2.749 × 10−42 | HCT-116 | 50.280 | 0.699 | 0.164 | 4.848 × 10−12 | |||

| HepG2 | 51.15 | 0.2141 | 3.049 × 10−5 | 1.010 × 10−16 | HepG2 | 163.000 | 0.214 | 0.071 | 8.043 × 10−16 |

| OA | HCPT | OA + HCPT Mixture | OA/HCPT-NPs | UA | HCPT | UA + HCPT Mixture | UA/HCPT-NPs | Title 1 | Title 2 | Title 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A375 | 22.430 | 0.305 | 0.243 | 7.961 × 10−8 | A375 | 0.104 | 0.305 | 0.2363 | 4.538 × 10−10 | entry 1 | data | data |

| AGS | - | 1.923 | 0.608 | 3.202 × 10−13 | AGS | 115.100 | 1.923 | 0.450 | 0.116 | entry 2 | data | data |

| HCT-116 | 10.080 | 0.699 | 4.908 × 10−10 | 2.154 × 10−40 | HCT-116 | 50.280 | 0.699 | 0.164 | 4.848 × 10−12 | |||

| HepG2 | 0.5120 | 0.214 | 0.054 | 1.139 × 10−11 | HepG2 | 163.000 | 0.214 | 0.071 | 8.043 × 10−16 |

| BA | HCPT | BA + HCPT Mixture | BA/HCPT-NPs | UA | HCPT | UA + HCPT Mixture | UA/HCPT-NPs | Title 1 | Title 2 | Title 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A375 | 45.890 | 0.305 | 0.235 | 2.606 × 10−7 | A375 | 0.104 | 0.305 | 0.2363 | 4.538 × 10−10 | entry 1 | data | data |

| AGS | 10.680 | 1.923 | 0.746 | 0.516 | AGS | 115.100 | 1.923 | 0.450 | 0.116 | entry 2 | data | data |

| HCT-116 | 24.040 | 0.699 | 0.039 | 5.575 × 10−16 | HCT-116 | 50.280 | 0.699 | 0.164 | 4.848 × 10−12 | |||

| HepG2 | 546.600 | 0.214 | 0.060 | 6.344 × 10−11 | HepG2 | 163.000 | 0.214 | 0.071 | 8.043 × 10−16 |

References

- Amadi, E.V.; Venkataraman, A.; Papadopoulos, C. Nanoscale Self-Assembly: Concepts, Applications and Challenges. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 132001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xia, D.; Klausen, L.H.; Dong, M. The Self-Assembled Behavior of DNA Bases on the Interface. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Jin, Y.; Liu, D. Self-Assembled Peptide Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Gels 2023, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Y.; Zhao, R.R.; Fang, Y.F.; Jiang, J.L.; Yuan, X.T.; Shao, J.W. Carrier-Free Nanodrug: A Novel Strategy of Cancer Diagnosis and Synergistic Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 570, 118663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Xiao, H.; Yuan, M.; Liu, Y.; Sedlařík, V.; Chin, W.-C.; Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, C. Self-Assembled Camptothecin Derivatives—Curcuminoids Conjugate for Combinatorial Chemo-Photodynamic Therapy to Enhance Anti-Tumor Efficacy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2021, 215, 112124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Jiang, B.; Hao, D.; Xie, Z. Self-Assembled Nanoformulations of Paclitaxel for Enhanced Cancer Theranostics. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 3252–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y. Engineering Self-Assembled Nanomedicines Composed of Clinically Approved Medicines for Enhanced Tumor Nanotherapy. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, K.; Morales, J.; Rodríguez, L.; Günther, G. Potential Use of Nanocarriers with Pentacyclic Triterpenes in Cancer Treatments. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 3139–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, J.; Guo, Q. Recent Advances of Natural Pentacyclic Triterpenoids as Bioactive Delivery System for Synergetic Biological Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Pharmacology of Oleanolic Acid and Ursolic Acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995, 49, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratheeshkumar, P.; Kuttan, G. Oleanolic Acid Induces Apoptosis by Modulating P53, Bax, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 Gene Expression and Regulates the Activation of Transcription Factors and Cytokine Profile in B16F. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2011, 30, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosny, S.; Sahyon, H.; Youssef, M.; Negm, A. Oleanolic Acid Suppressed DMBA-Induced Liver Carcinogenesis through Induction of Mitochondrial-Mediated Apoptosis and Autophagy. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarotti, G.; Cuomo, M.; Ragosta, M.C.; Russo, A.; D’Angelo, M.; Medugno, A.; Napolitano, G.M.; Iannuzzi, C.A.; Forte, I.M.; Camerlingo, R.; et al. Oleanolic Acid Modulates DNA Damage Response to Camptothecin Increasing Cancer Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Dong, S.; Zhou, W. Betulinic Acid in the Treatment of Tumour Diseases: Application and Research Progress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhong, H.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Su, C.; Gu, W.; Qian, Y. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) from Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Promote Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell (HUVEC) Angiogenesis through Yes Kinase-Associated Protein (YAP) Transport. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2110–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Uddin, S.J.; Khan, I.N.; Shill, M.C.; de Castro E Sousa, J.M.; de Alencar, M.V.O.B.; Melo-Cavalcante, A.A.C.; Mubarak, M.S. Anti-Cancer Effects of Asiatic Acid, a Triterpene from Centilla Asiatica L: A Review. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiciński, M.; Fajkiel-Madajczyk, A.; Kurant, Z.; Gajewska, S.; Kurant, D.; Kurant, M.; Sousak, M. Can Asiatic Acid from Centella Asiatica Be a Potential Remedy in Cancer Therapy?-A Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Y. Asiatic Acid in Anticancer Effects: Emerging Roles and Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1545654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Su, M.; Xu, F.; Yang, L.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Z. Advances in Antitumor Nano-Drug Delivery Systems of 10-Hydroxycamptothecin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 4227–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lv, L.; Jiang, C.; Bai, J.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, P. A Natural Product, (S)-10-Hydroxycamptothecin Inhibits Pseudorabies Virus Proliferation through DNA Damage Dependent Antiviral Innate Immunity. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 265, 109313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Pang, N.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Qi, X. Preparation, characterization and pharmacokinetics of 10-hydroxycamptothecin nanosuspension. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 26, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Hong, J.; Ding, Z.; Liu, M.; Han, J. Novel Carrier-Free Nanoparticles Composed of 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin and Chlorin E6: Self-Assembly Mechanism Investigation and in Vitro/in Vivo Evaluation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Hu, H.; Jing, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, B.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. A Modular ROS-Responsive Platform Co-Delivered by 10-Hydroxycamptothecin and Dexamethasone for Cancer Treatment. J. Control Release 2021, 340, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xue, X.; Zhang, X.; Kumar, A.; Liang, X.-J. Synergistically Enhanced Therapeutic Effect of a Carrier-Free HCPT/DOX Nanodrug on Breast Cancer Cells through Improved Cellular Drug Accumulation. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, B.G.; Majumdar, R. Self-Assembly of Renewable Nano-Sized Triterpenoids. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 841–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Xu, H. Oleanolic Acid Nanosuspensions: Preparation, in-Vitro Characterization and Enhanced Hepatoprotective Effect. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2005, 57, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Kebebe, D.; Pi, J.; Guo, P. Construction of Curcumin-Loaded Micelles and Evaluation of the Anti-Tumor Effect Based on Angiogenesis. Acupunct. Herbal. Med. 2023, 3, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, B.; Gong, H.; Luk, B.T.; Haushalter, K.J.; DeTeresa, E.; Previti, M.; Zhou, J.; Gao, W.; Bui, J.D.; Zhang, L.; et al. Intratumoral Immunotherapy Using Platelet-Cloaked Nanoparticles Enhances Antitumor Immunity in Solid Tumors. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Huang, C.; Wu, S.; Yin, M. Oleanolic Acid and Ursolic Acid Induce Apoptosis in Four Human Liver Cancer Cell Lines. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wan, C.; Zou, Z.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; Geng, Y.; Chen, T.; Huang, A.; Jiang, F.; Feng, J.-P.; et al. Tumor Ablation and Therapeutic Immunity Induction by an Injectable Peptide Hydrogel. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3295–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjad, H.; Imtiaz, S.; Noor, T.; Siddiqui, Y.H.; Sajjad, A.; Zia, M. Cancer Models in Preclinical Research: A Chronicle Review of Advancement in Effective Cancer Research. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2021, 4, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, J.N. Ki67 Is a Promising Molecular Target in the Diagnosis of Cancer (Review). Mol Med Rep 2015, 11, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yuan, L.; Chou, W.-C.; Cheng, Y.-H.; He, C.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Riviere, J.E.; Lin, Z. Meta-Analysis of Nanoparticle Distribution in Tumors and Major Organs in Tumor-Bearing Mice. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19810–19831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookoian, S.; Pirola, C.J. Liver Enzymes, Metabolomics and Genome-Wide Association Studies: From Systems Biology to the Personalized Medicine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohabbati-Kalejahi, E.; Azimirad, V.; Bahrami, M.; Ganbari, A. A Review on Creatinine Measurement Techniques. Talanta 2012, 97, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, G.; Zang, W.; Zhou, X.; Shi, K.; Zhai, Y. Pure Drug Nano-Assemblies: A Facile Carrier-Free Nanoplatform for Efficient Cancer Therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Lian, Y.; Cheng, J.; Liu, H.; Du, G.; Shi, J. Engineering an Advanced Multicomponent Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Nanoplatform for Synergistic Co-Delivery of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors to Enhance Cancer Chemoimmunotherapy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 699, 138203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Hu, Y.; Yang, W.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Hou, X.; Shen, P.; Jian, R.; Liu, Z.; Pi, J. Preparation and Antitumor Evaluation of Four Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and 10-Hydroxycamptothecin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121577

Zhang T, Hu Y, Yang W, Huang X, Zhang L, Hou X, Shen P, Jian R, Liu Z, Pi J. Preparation and Antitumor Evaluation of Four Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and 10-Hydroxycamptothecin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121577

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tingen, Yiwen Hu, Wenzhuo Yang, Xiaochao Huang, Linhui Zhang, Xiaotong Hou, Pengyu Shen, Ruihong Jian, Zhidong Liu, and Jiaxin Pi. 2025. "Preparation and Antitumor Evaluation of Four Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and 10-Hydroxycamptothecin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121577

APA StyleZhang, T., Hu, Y., Yang, W., Huang, X., Zhang, L., Hou, X., Shen, P., Jian, R., Liu, Z., & Pi, J. (2025). Preparation and Antitumor Evaluation of Four Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and 10-Hydroxycamptothecin Self-Assembled Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121577