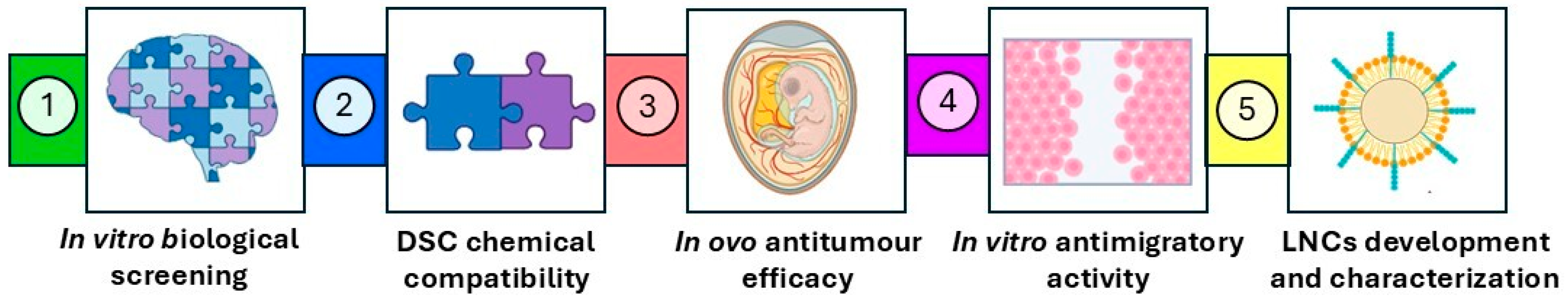

From Screening to a Nanotechnological Platform: Cannabidiol–Chemotherapy Co-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Glioblastoma Multiforme Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay in U-87 MG and U-373 MG Cells

2.2.1. In Vitro Monotherapy Studies

2.2.2. In Vitro Combination Studies

2.3. Chemical Compatibility Between CBD and Chemotherapeutics

2.4. Wound Healing Assay

2.5. Antitumour Efficacy Using the Hen Egg Test-Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM) Assay

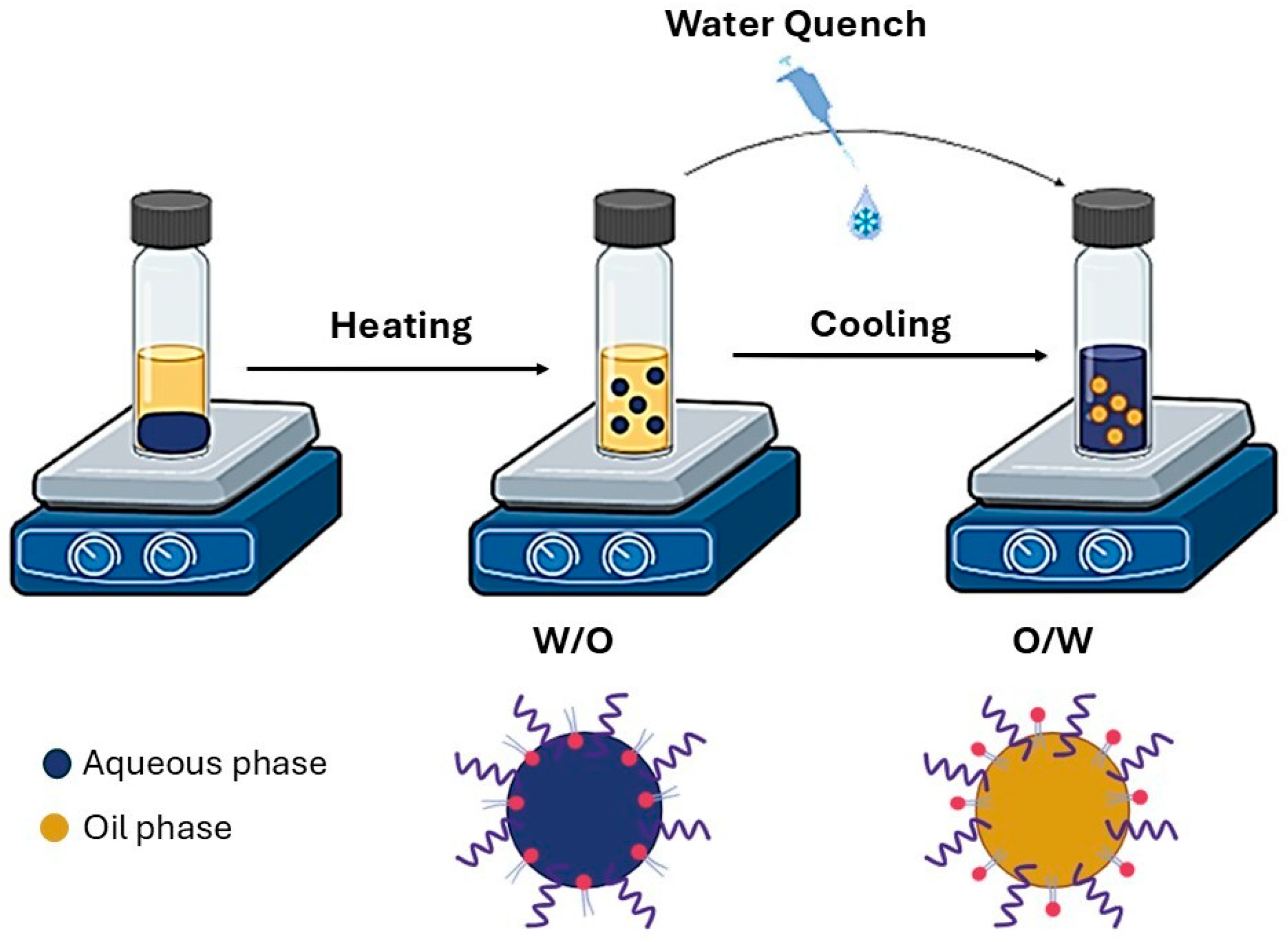

2.6. Preparation of LNCs

2.6.1. Blank-LNCs

2.6.2. CBD and PTX Co-Loaded LNCs

2.7. Characterization of LNCs

2.7.1. Size Distribution

2.7.2. ζ-Potential

2.7.3. Morphology

2.7.4. Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Content

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

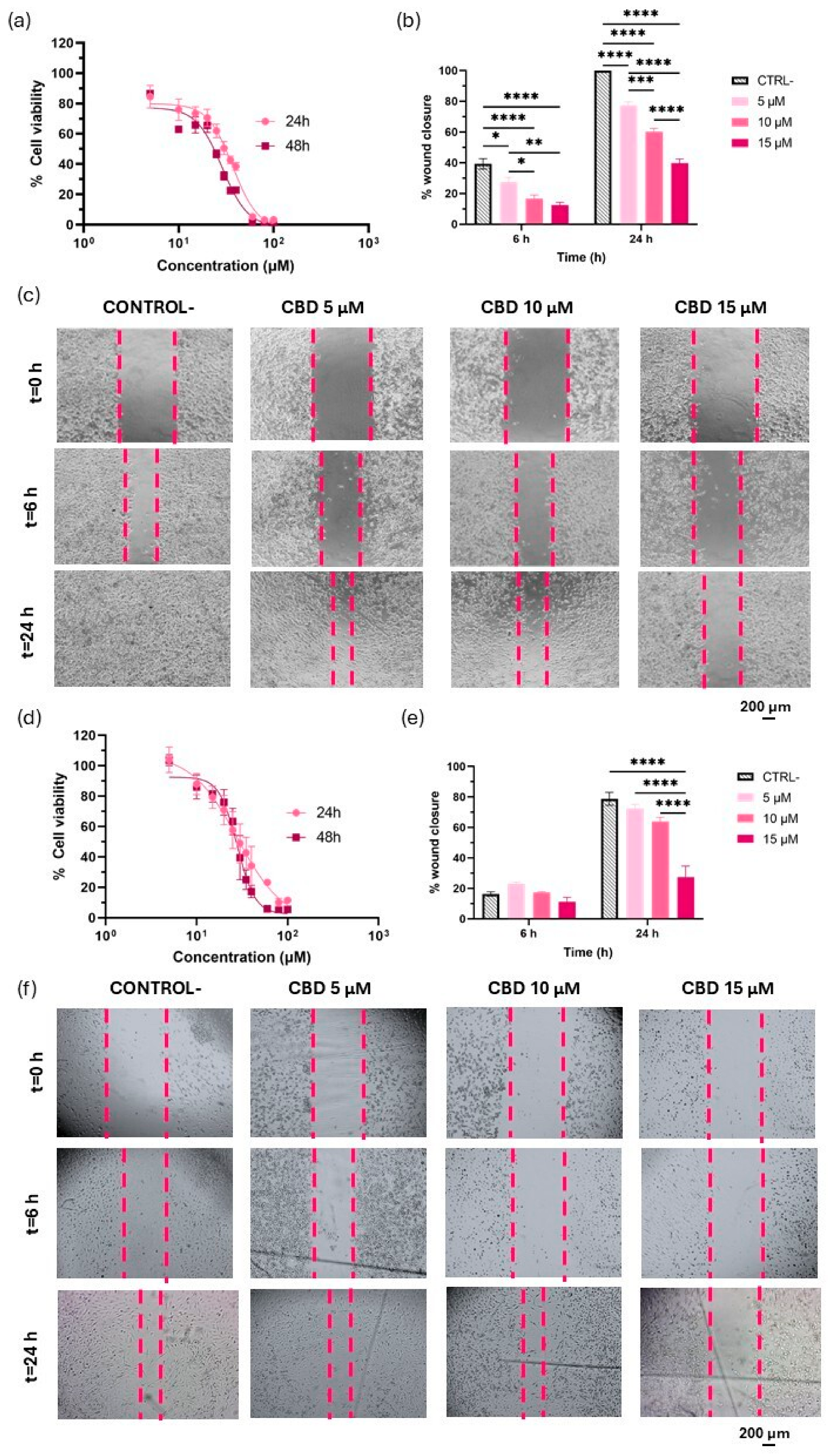

3.1. Evaluation of CBD as a Modulator of Proliferation and Migration in GBM

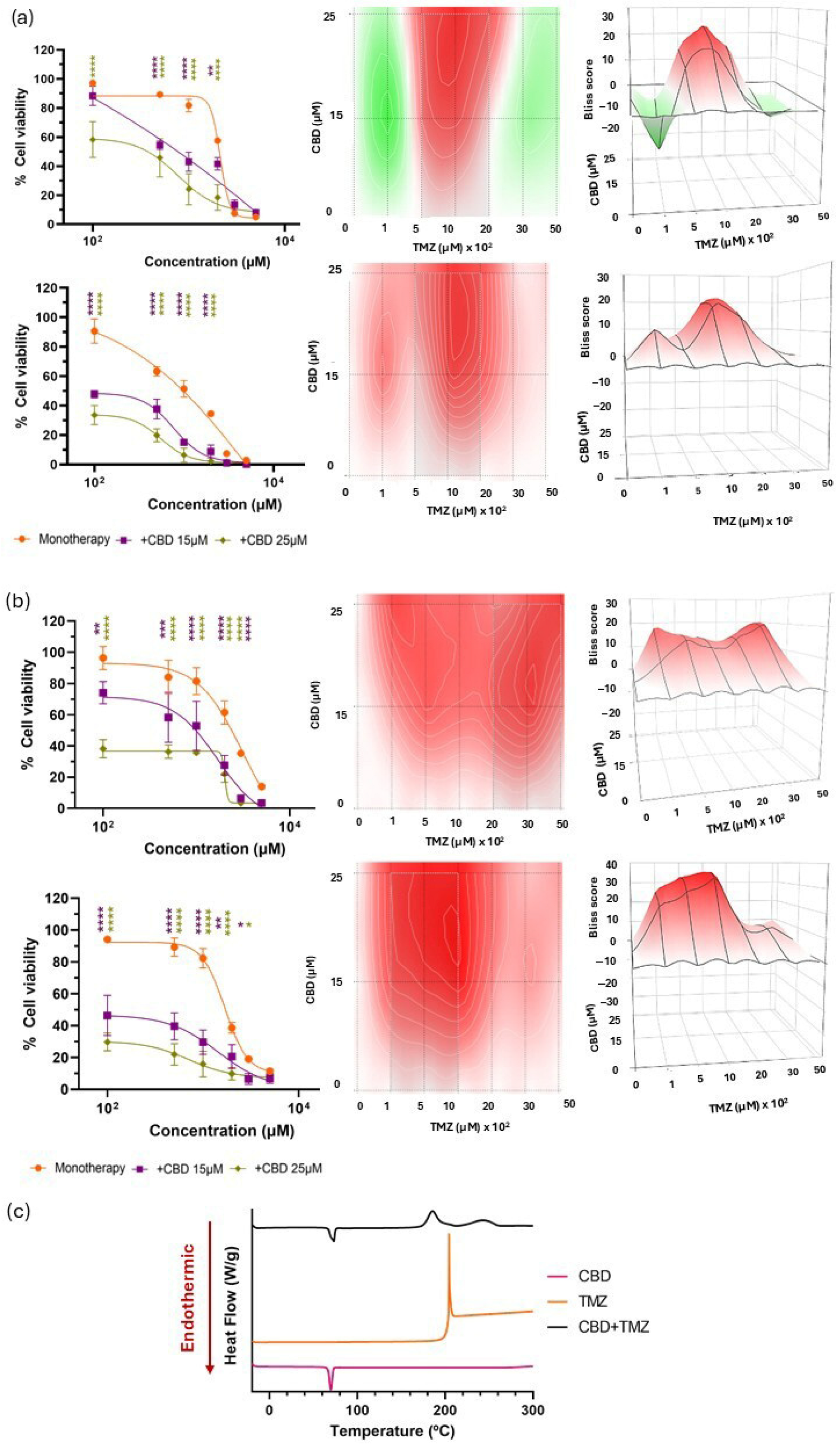

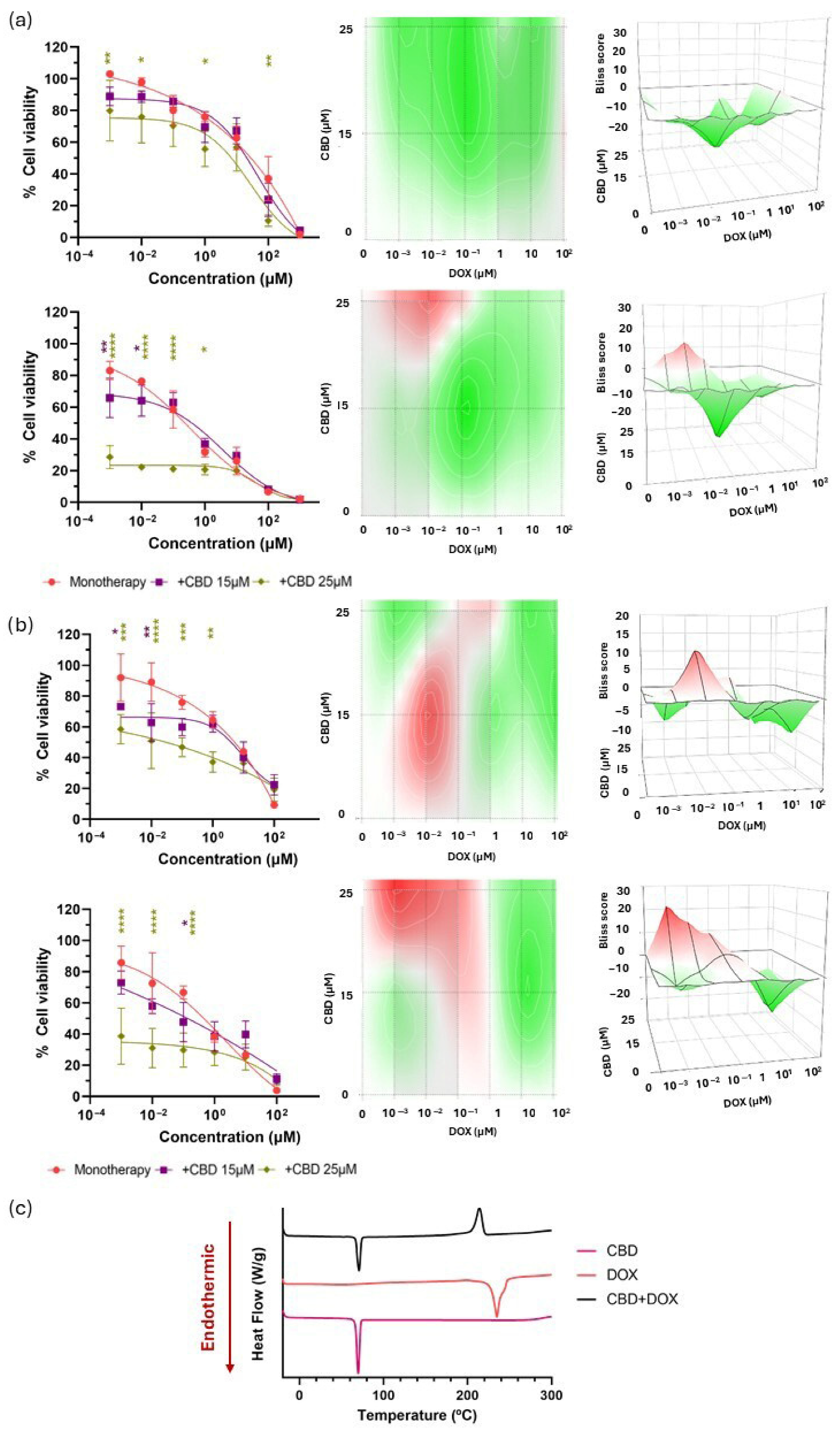

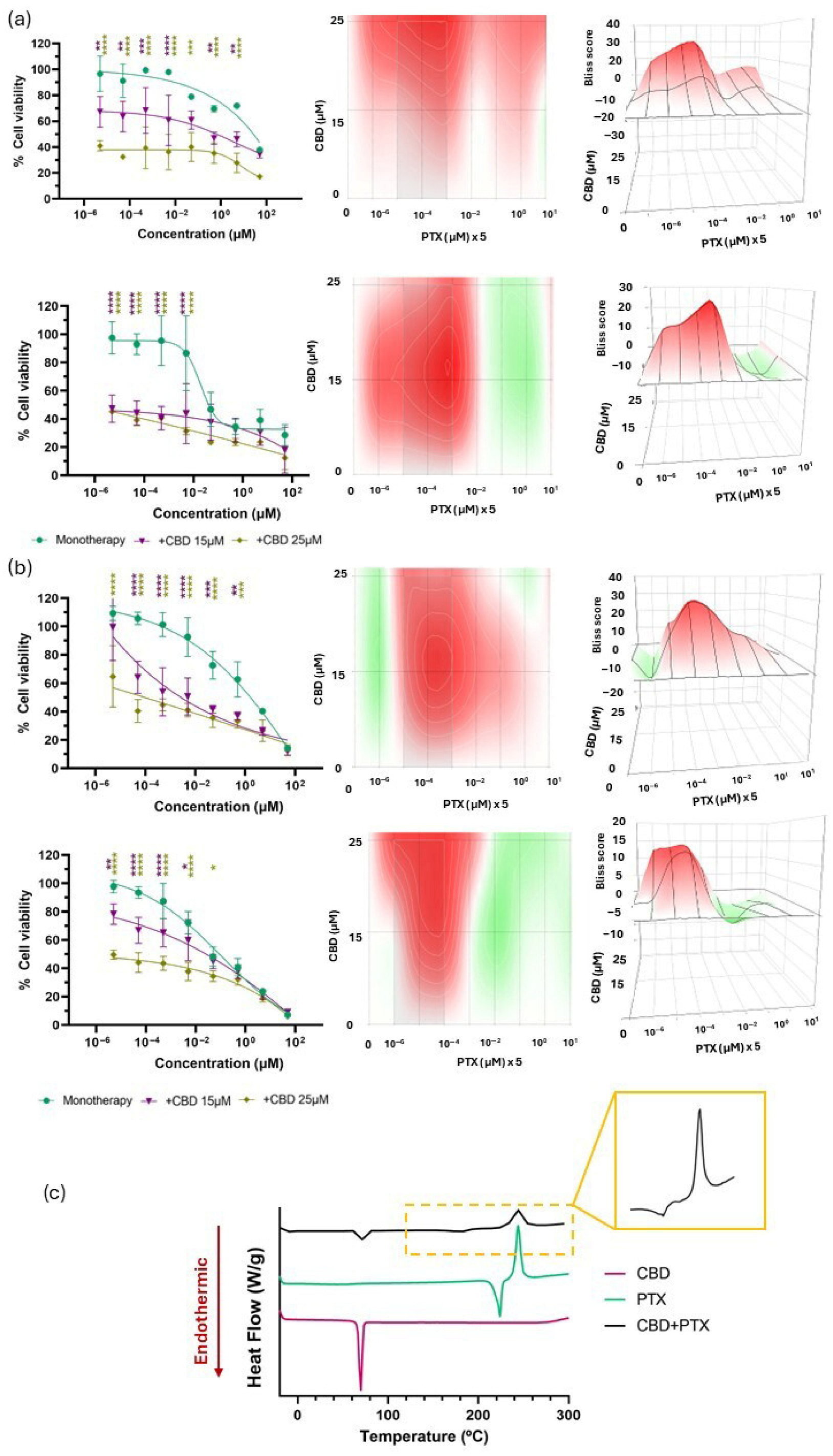

3.2. Biological and Chemical Screening of CBD and Chemotherapy Combinations

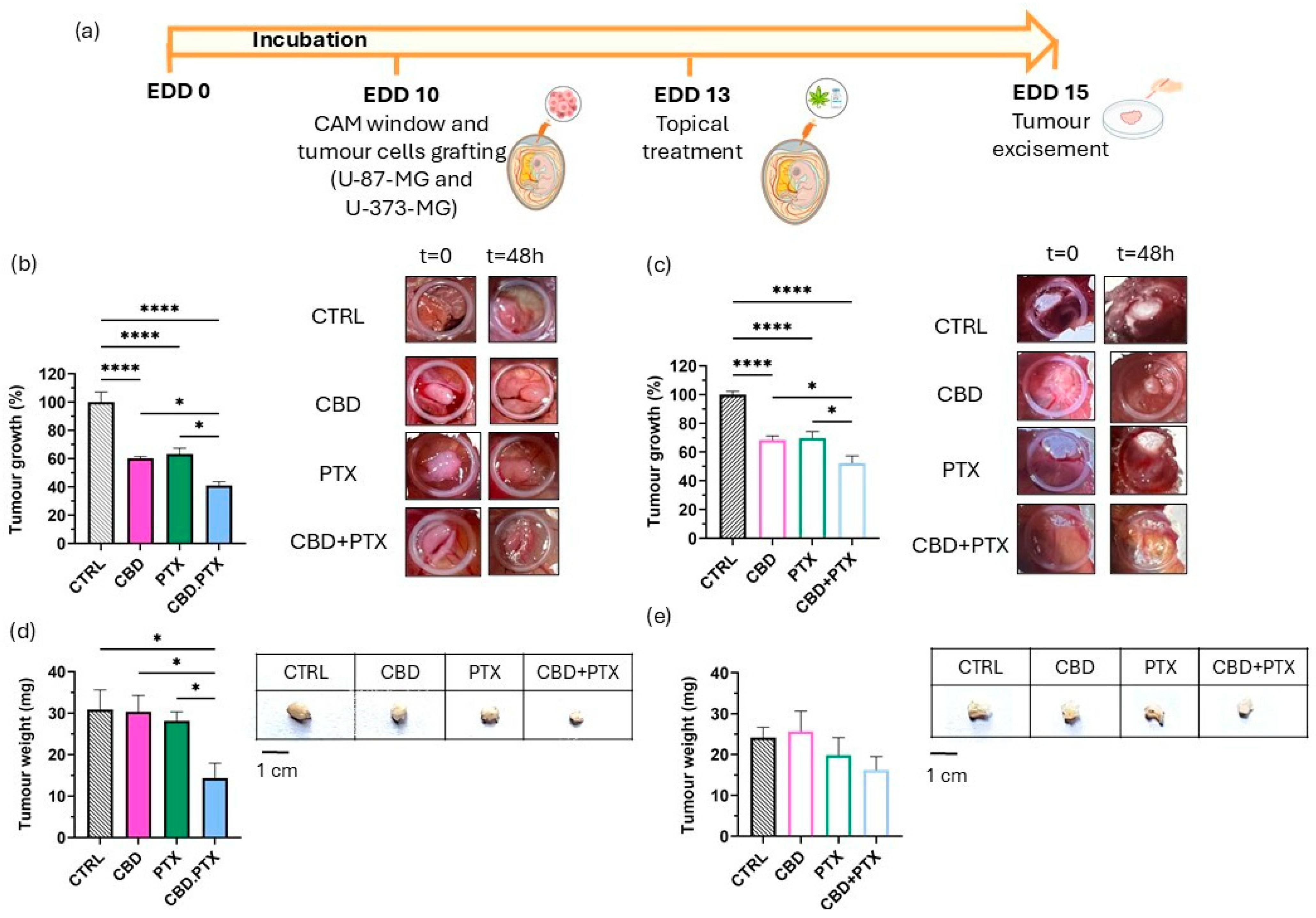

3.3. In Ovo Evaluation of Antitumour Efficacy in the HET-CAM Model Using U-87 MG and U-373 MG Glioblastoma Xenografts

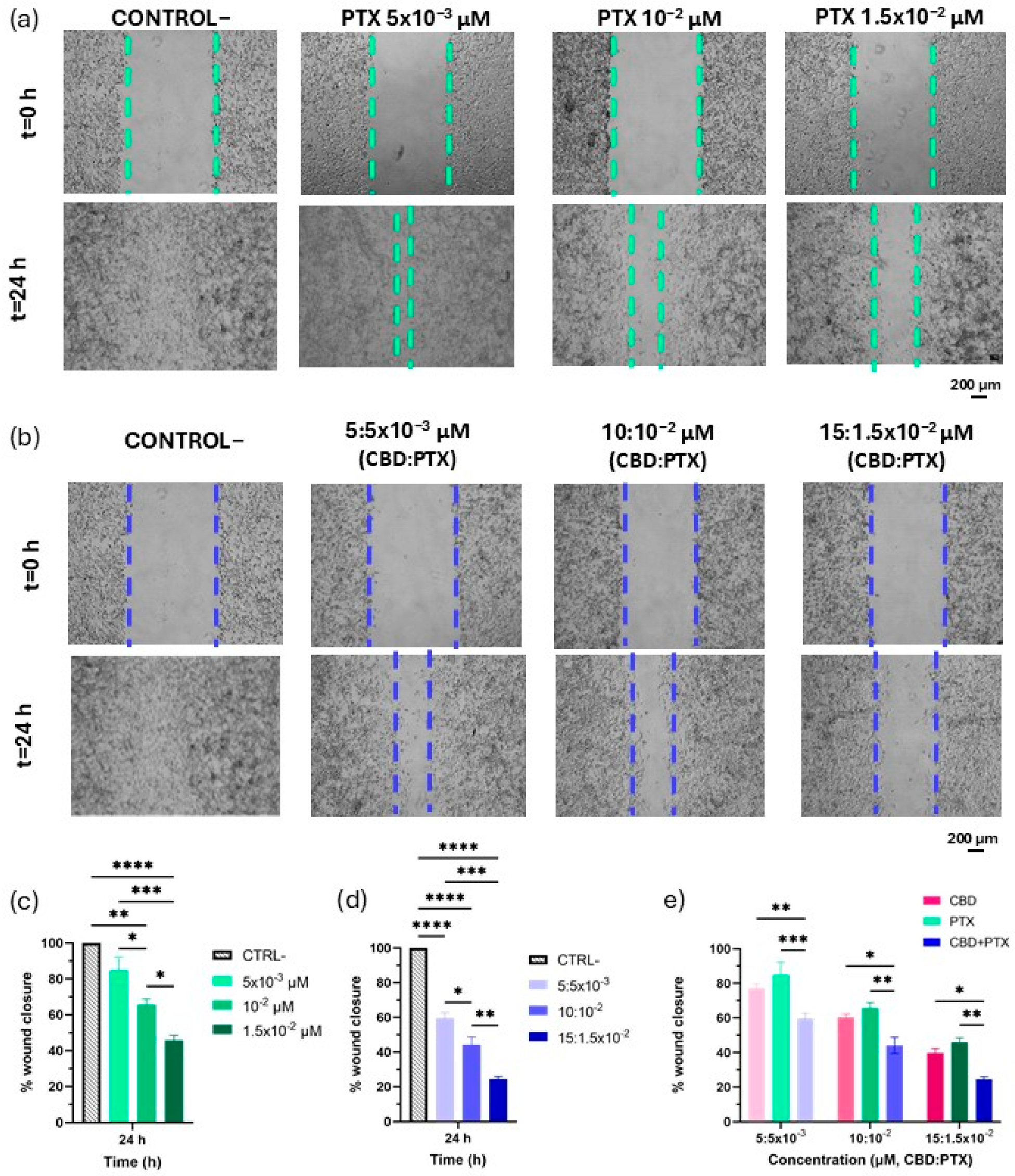

3.4. PTX and CBD + PTX Anti-Migratory Activity

3.5. LNCs Formulation and Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cherkasova, V.; Ilnytskyy, Y.; Kovalchuk, O.; Kovalchuk, I. Transcriptome Analysis of Cisplatin, Cannabidiol, and Intermittent Serum Starvation Alone and in Various Combinations on Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.S.; Marie, M.A.; Sheweita, S.A. Novel mechanism of cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines. Breast 2018, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, E.; Khalifa, K.; Cosgrave, J.; Azam, H.; Prencipe, M.; Simpson, J.C.; Gallagher, W.M.; Perry, A.S. Cannabidiol Inhibits the Proliferation and Invasiveness of Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofano, F.; Sharma, A.; Abken, H.; Gonzalez-Carmona, M.A.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.H. A Low Dose of Pure Cannabidiol Is Sufficient to Stimulate the Cytotoxic Function of CIK Cells without Exerting the Downstream Mediators in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, F.; Zhou, H.; Ma, N.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; Jin, G.; Wu, S.; Hong, W.; Zhuang, W.; Xia, H.; et al. A Novel Mechanism of Cannabidiol in Suppressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inducing GSDME Dependent Pyroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 697832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Tamia, G.; Song, H.J.; Amarakoon, D.; Wei, C.I.; Lee, S.H. Cannabidiol exerts anti-proliferative activity via a cannabinoid receptor 2-dependent mechanism in human colorectal cancer cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabissi, M.; Morelli, M.B.; Offidani, M.; Amantini, C.; Gentili, S.; Soriani, A.; Cardinali, C.; Leoni, P.; Santoni, G. Cannabinoids synergize with carfilzomib, reducing multiple myeloma cells viability and migration. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77543–77557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surapaneni, S.K.; Patel, N.; Sun, L.; Kommineni, N.; Kalvala, A.K.; Gebeyehu, A.; Arthur, P.; Duke, L.C.; Nimma, R.; Meckes, D.G., Jr.; et al. Anticancer and chemosensitization effects of cannabidiol in 2D and 3D cultures of TNBC: Involvement of GADD45α, integrin-α5,-β5,-β1, and autophagy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 2762–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luís, Â.; Marcelino, H.; Rosa, C.; Domingues, F.; Pereira, L.; Cascalheira, J.F. The effects of cannabinoids on glioblastoma growth: A systematic review with meta-analysis of animal model studies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 876, 173055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Insights into the effects of the endocannabinoid system in cancer: A review. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2566–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alifieris, C.; Trafalis, D.T. Glioblastoma multiforme: Pathogenesis and treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 152, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; Fisher, B.; Belanger, K.; et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, M.; Duarte, M.J.; Blázquez, C.; Ravina, J.; Rosa, M.C.; Galve-Roperh, I.; Sánchez, C.; Velasco, G.; González-Feria, L. A pilot clinical study of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.; Renard, J.; Norris, C.; Rushlow, W.J.; Laviolette, S.R. Cannabidiol counteracts the psychotropic side-effects of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the ventral hippocampus through bidirectional control of erk1-2 phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8762–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twelves, C.; Sabel, M.; Checketts, D.; Miller, S.; Tayo, B.; Jove, M.; Brazil, L.; Short, S.C. A phase 1b randomised, placebo-controlled trial of nabiximols cannabinoid oromucosal spray with temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, J.M.; Alonso, M.; Velilla, G.; Grove, C.G.; Martínez-García, M.; Foro, P.; Garcia Gonzalez, C.; Muriel Lopez, C.; Luque, R.; Luque, N.; et al. 454P Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)/cannabidiol (CBD) oral solution in combination with temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy (RT) in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: Phase Ib GEINO-1601 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, D.; Savage, J.; Patel, A.; Collinson, F.; Mant, R.; Boele, F.; Brazil, L.; Meade, S.; Buckle, P.; Lax, S.; et al. A randomised phase II trial of temozolomide with or without cannabinoids in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (ARISTOCRAT): Protocol for a multi-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izgelov, D.; Davidson, E.; Barasch, D.; Regev, A.; Domb, A.J.; Hoffman, A. Pharmacokinetic investigation of synthetic cannabidiol oral formulations in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 154, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, B.; Baratta, F.; Della Pepa, C.; Arpicco, S.; Gastaldi, D.; Dosio, F. Cannabinoid Formulations and Delivery Systems: Current and Future Options to Treat Pain. Drugs 2021, 18, 1513–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, C.G.; White, L.; Wright, S.; Wilbraham, D.; Guy, G.W. A phase I study to assess the single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of THC/CBD oromucosal spray. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.B.; Duarte, J.L.; Di Filippo, L.D.; Chorilli, M. Improving the Biopharmaceutical Properties of Cannabinoids in Glioblastoma Multiforme Therapy With Nanotechnology: A Drug Delivery Perspective. Drug Dev. Res. 2024, 85, 70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Sebastián, V.; Rodríguez-Amaro, M.; García-Díaz, H.C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Size-tailored design of highly monodisperse lipid nanocapsules for drug delivery. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2019, 16, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Lipid nanocapsules: Latest advances and applications. In Fundamentals of Pharmaceutical Nanoscience; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Sebastián, V.; Benoit, J.P.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Lipid nanocapsules decorated and loaded with cannabidiol as targeted prolonged release carriers for glioma therapy: In vitro screening of critical parameters. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 134, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; He, L.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J. SynergyFinder: A web application for analyzing drug combination dose-response matrix data. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2413–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Wennerberg, K.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J. Searching for Drug Synergy in Complex Dose–Response Landscapes Using an Interaction Potency Model. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Giri, A.K.; Aittokallio, T. SynergyFinder 2.0: Visual analytics of multi-drug combination synergies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 48, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grada, A.; Otero-Vinas, M.; Prieto-Castrillo, F.; Obagi, Z.; Falanga, V. Research Techniques Made Simple: Analysis of Collective Cell Migration Using the Wound Healing Assay. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, E.; Weaver, E.; Meziane, A.; Lamprou, D.A. Microfluidic paclitaxel-loaded lipid nanoparticle formulations for chemotherapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 628, 122320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Schiano Moriello, A.; Iappelli, M.; Verde, R.; Stott, C.G.; Cristino, L.; Orlando, P.; Di Marzo, V. Non-THC cannabinoids inhibit prostate carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo: Pro-apoptotic effects and underlying mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Starowicz, K.; Matias, I.; Pisanti, S.; De Petrocellis, L.; Laezza, C.; Portella, G.; Bifulco, M.; Di Marzo, V. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramer, R.; Bublitz, K.; Freimuth, N.; Merkord, J.; Rohde, H.; Haustein, M.; Borchert, P.; Schmuhl, E.; Linnebacher, M.; Hinz, B. Cannabidiol inhibits lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis via intercellular adhesion molecule-1. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, J.L.; Park, S.H.; Na, Y.J.; Jo, M.J.; Yun, H.K.; Jeong, Y.A.; et al. Cannabidiol overcomes oxaliplatin resistance by enhancing NOS3- and SOD2-Induced autophagy in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, N.Q.; Meesiripan, N.; Sanggrajang, S.; Suwanpidokkul, N.; Prayakprom, P.; Bodhibukkana, C.; Khaowroongrueng, V.; Suriyachan, K.; Thanasitthichai, S.; Srisubat, A.; et al. Anti-proliferative and apoptotic effect of cannabinoids on human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma xenograft in BALB/c nude mice model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, C.G.; Itenberg, S.A.; Rao, J.; Ma, H.; Wu, X. Mechanisms of Cannabidiol (CBD) in Cancer Treatment: A Review. Biology 2022, 11, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabissi, M.; Morelli, M.B.; Santoni, G. Triggering of the TRPV2 channel by cannabidiol sensitizes glioblastoma cells to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, P.; Vaccani, A.; Ceruti, S.; Colombo, A.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Parolaro, D. Antitumor Effects of Cannabidiol, a Nonpsychoactive Cannabinoid, on Human Glioma Cell Lines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Ng, L.; Ozawa, T.; Stella, N. Quantitative analyses of synergistic responses between cannabidiol and DNA-damaging agents on the proliferation and viability of glioblastoma and neural progenitor cells in culture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 360, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Lorente, M.; Rodríguez-Fornés, F.; Hernández-Tiedra, S.; Salazar, M.; García-Taboada, E.; Barcia, J.; Guzmán, M.; Velasco, G. A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, J.P.; Christian, R.T.; Lau, D.; Zielinski, A.J.; Horowitz, M.P.; Lee, J.; Pakdel, A.; Allison, J.; Limbad, C.; Moore, D.H.; et al. Cannabidiol enhances the inhibitory effects of Δ9tetrahydrocannabinol on human glioblastoma cell proliferation and survival. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 9, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.A.; Dalgleish, A.G.; Liu, W.M. The Combination of Cannabidiol and D9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Enhances the Anticancer Effects of Radiation in an Orthotopic Murine Glioma Model. Small Mol. Ther. 2014, 13, 2955–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lozano, D.C.; Velázquez-Vázquez, D.E.; Del Moral-Morales, A.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Dihydrotestosterone induces proliferation, migration, and invasion of human glioblastoma cell lines. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 8813–8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seker-Polat, F.; Degirmenci, N.P.; Solaroglu, I.; Bagci-Onder, T. Tumor Cell Infiltration into the Brain in Glioblastoma: From Mechanisms to Clinical Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, E.; Yoon, H. Modeling and Predicting the Cell Migration Properties from Scratch Wound Healing Assay on Cisplatin-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines Using Artificial Neural Network. Healthcare 2021, 19, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, M.; Hage MEl Shebaby, W.; Al Toufaily, S.; Ismail, J.; Naim, H.Y.; Mroueh, M.; Rizk, S. The molecular anti-metastatic potential of CBD and THC from Lebanese Cannabis via apoptosis induction and alterations in autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, K.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, P. Chemoresistance caused by the microenvironment of glioblastoma and the corresponding solutions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, A.; Shakeel, F.; Raish, M.; Ahmad, A.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Al-Jenoobi, F.I.; Al-Mohizea, A.M. Thermodynamic Solubility Profile of Temozolomide in Different Commonly Used Pharmaceutical Solvents. Molecules 2022, 27, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, S.L.; Chang, T.R.; You, Y.; Wang, X.D.; Wang, L.W.; Yuan, X.F.; Tan, M.H.; Wang, P.D.; Xu, P.W.; et al. Inclusion complexes of cannabidiol with b -cyclodextrin and its derivative: Physicochemical properties, water solubility, and antioxidant activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.A.; Antonoaea, P.; Todoran, N.; Muntean, D.L.; Rédai, E.M.; Silasi, O.A.; Tătaru, A.; Bîrsan, M.; Imre, S.; Ciurba, A. Pharmacotechnical and analytical preformulation studies for cannabidiol orodispersible tablets. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, M.; Hilt, D.C.; Bortey, E.; Delavault, P.; Olivares, R.; Warnke, P.C.; Whittle, I.R.; Jääskeläinen, J.; Ram, Z. A phase 3 trial of local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) wafers (Gliadel wafers) in patients with primary malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2004, 5, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painbeni, T.; Benoit, J.P. Internal morphology of poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) BCNU-loaded microspheres. Influence on drug stability. J. Microencapsul. 1998, 45, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujwar, S.; Kołat, D.; Kciuk, M.; Gieleci, A.; Kałuzi, Z. Doxorubicin—An Agent with Multiple Mechanisms of Anticancer Activity. Cells 2023, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riganti, C.; Voena, C.; Kopecka, J.; Corsetto, P.A.; Montorfano, G.; Enrico, E.; Costamagna, C.; Rizzo, A.M.; Ghigo, D.; Bosia, A. Liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin reverses drug resistance by inhibiting P-glycoprotein in human cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2011, 8, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani, M.; Azizi, Y.; Shayan, M.; Nezamoleslami, S.; Eslami, F. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An Overview on Pre-clinical Therapeutic Approaches. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, E.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Cao, Z.; Erdélyi, K.; Holovac, E.; Liaudet, L.; Lee, W.S.; Haskó, G.; Mechoulam, R.; Pacher, P. Cannabidiol Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy by Modulating Mitochondrial Function and Biogenesis. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, C.; Tai, G.; Ruan, B. Local penetration of doxorubicin via intrahepatic implantation of PLGA based doxorubicin-loaded implants. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.T.; Goh, B.H.; Lee, W.L. Taxol: Mechanisms of Action Against Cancer, an Update with Current Research; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Guideline: Biopharmaceutics Classification System-Based Biowaivers M9; M9 Guideline; The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa, Y.; Ogawara, K.I.; Kimura, T.; Higaki, K. A novel approach to overcome multidrug resistance: Utilization of P-gp mediated efflux of paclitaxel to attack neighboring vascular endothelial cells in tumors. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 62, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huehnchen, P.; Boehmerle, W.; Endres, M. Assessment of Paclitaxel Induced Sensory Polyneuropathy with “Catwalk” Automated Gait Analysis in Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 76772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinov, I.; Shahul, S.; Tung, A.; Minhaj, M.; Nizamuddin, J.; Wenger, J.; Mahmood, E.; Mueller, A.; Shaefi, S.; Scavone, B.; et al. Pathogenesis of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: A current review of in vitro and in vivo findings using rodent and human model systems. Physiol Behav. 2017, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Creanga-Murariu, I.; Filipiuc, L.E.; Gogu, M.R.; Ciorpac, M.; Cumpat, C.M.; Tamba, B.I.; Alexa-Strătulat, T. The potential neuroprotective effects of cannabinoids against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: In vitro study on neurite outgrowth. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1395951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.J.; McAllister, S.D.; Kawamura, R.; Murase, R.; Neelakantan, H.; Walker, E.A. Cannabidiol inhibits paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain through 5-HT 1A receptors without diminishing nervous system function or chemotherapy efficacy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.F.; Larsen, B.S.; Nielsen, R.B.; Pijpers, I.; Versweyveld, D.; Holm, R.; Tho, I.; Snoeys, J.; Nielsen, C.U. Co-release of paclitaxel and encequidar from amorphous solid dispersions increase oral paclitaxel bioavailability in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 654, 123965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Berner, J.; Bekeschus, S. In ovo model in cancer research and tumor immunology. Front. Inmunol. 2022, 13, 1006064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Zeisser-Labouèbe, M.; Lange, N.; Gurny, R.; Delie, F. The chick embryo and its chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) for the in vivo evaluation of drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Cohen, M.; Delie, F.; Bastida-Ruiz, D.; Yart, L.; Martin-Sabroso, C.; Fernández-Carballido, A. PLGA Nanoparticles for the Intraperitoneal Administration of CBD in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: In Vitro and In Ovo Assessment. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Fernández-Carballido, A.; Simancas-Herbada, R.; Martin-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. CBD loaded microparticles as a potential formulation to improve paclitaxel and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 574, 118916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutzke, L.; Allmendinger, E.; Hirt, K.; Kochanek, S. Chorioallantoic Membrane Tumor Model for Evaluating Oncolytic Viruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 1100–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privat-Maldonado, A.; Verloy, R.; Delahoz, E.C.; Lin, A.; Vanlanduit, S.; Smits, E.; Bogaerts, A. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Does Not Affect Stellate Cells Phenotype in Pancreatic Cancer Tissue in Ovo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Model: A Research Approach for Ex Vivo and In Vivo Experiments. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 1702–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Badana, A.K.; Mohan, G.M.; Naik, G.S.; Malla, R.R. Synergistic effects of coralyne and paclitaxel on cell migration and proliferation of breast cancer cell lines. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Decker, C.C.; Zechner, L.; Krstin, S.; Wink, M. In vitro wound healing of tumor cells: Inhibition of cell migration by selected cytotoxic alkaloids. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Wu, T.; Yin, Q.; Gu, X.; Li, G.; Zhou, C.; Ma, M.; Su, L.; Tang, S.; Tian, Y.; et al. Combination of Paclitaxel and PXR Antagonist SPA70 Reverses Paclitaxel-Resistant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. Taxol-induced polymerization of purified tubulin: Mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 10435–10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foland, T.B.; Dentler, W.L.; Suprenant, K.A.; Gupta MLJr Himes, R.H. Paclitaxel-induced microtubule stabilization causes mitotic block and apoptotic-like cell death in a paclitaxel-sensitive strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2005, 22, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.A.; Kamath, K. How do microtubule targeted drugs work? An overview. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2007, 7, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.S.; Asevedo, E.A.; Duarte-Almeida, J.M.; Nurkolis, F.; Syahputra, R.A.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B.; Couto, R.O.; Ribeiro, R.I. Mechanisms of Cell Death Induced by Cannabidiol Against Tumor Cells: A Review of Preclinical Studies. Plants 2025, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śledziński, P.; Zeyland, J.; Słomski, R.; Nowak, A. The current state and future perspectives of cannabinoids in cancer biology. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viudez-Martínez, A.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrón, C.M.; Morales-Calero, M.I.; Navarrete, F.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Manzanares, J. Cannabidiol reduces ethanol consumption, motivation and relapse in mice. Addict. Biol. 2017, 23, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Shu, P.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, T.; Fan, W.; Lu, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Preclinical Development and Phase I Study of ZSYY001, a Polymeric Micellar Paclitaxel for Advanced Solid Tumor. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, 71039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwema, A.; Gratpain, V.; Ucakar, B.; Vanvarenberg, K.; Perdaens, O.; van Pesch, V.; Muccioli, G.G.; des Rieux, A. Impact of calcitriol and PGD2-G-loaded lipid nanocapsules on oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation and remyelination. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 3128–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrak, Y.; Alhouayek, M.; Mwema, A.; D’Auria, L.; Ucakar, B.; van Pesch, V.; Muccioli, G.G.; des Rieux, A. The combined administration of LNC-encapsulated retinoic acid and calcitriol stimulates oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation in vitro and in vivo after intranasal administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 659, 124237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, N.; Fauvet, F.; Ruby, S.; Puisieux, A.; Paquot, A.; Muccioli, G.G.; Vigneron, A.M.; Préat, V. Combined nanomedicines targeting colorectal cancer stem cells and cancer cells. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Du, B.; Ning, X.; Tang, S.; Bachoo, R.M.; Yu, M.; Ge, W.-P.; Zheng, J. Targeting orthotopic gliomas with renal-clearable luminescent gold nanoparticles. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, E.; Zhang, C.; Shih, T.-Y.; Schister, B.S.; Hanes, J. Brain-Penetrating Nanoparticles Improve Paclitaxel Efficacy in Malignant Glioma Following Local Administration. ACS Nano 2014, 10, 10655–10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, O.; Lagarce, F. Lipid nanocapsules: A nanocarrier suitable for scale up process. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2013, 23, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, B.; Shi, H.; Li, Z.; Ran, G. Targeted reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages for overcoming glioblastoma resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2024, 311, 122708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, J.R.; Boraie, N.A.; Ismail, F.A.; Bakr, B.A.; Allam, E.A.; El-Moslemany, R.M. Brain targeted lactoferrin coated lipid nanocapsules for the combined effects of apocynin and lavender essential oil in PTZ induced seizures. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 15, 534–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrua, E.C.; Hartwig, O.; Loretz, B.; Murgia, X.; Ho, D.-K.; Bastiat, G.; Lehr, C.-M.; Salomon, C.J. Formulation of benznidazole-lipid nanocapsules: Drug release, permeability, biocompatibility, and stability studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 642, 123120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Li, P.; Fu, D.; Yang, F.; Sui, X.; Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Chi, J. CBD-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Optimization, Characterization, and Stability. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 40632–40643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, I.E.; ElSohly, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; Elkanayati, R.M.; Wanas, A.; Joshi, P.H.; Ashour, E.A. Enhancement of cannabidiol oral bioavailability through the development of nanostructured lipid carriers: In vitro and in vivo evaluation studies. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 2722–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, F.V.; Geronimo, G.; de Moura, L.D.; Mendonça, T.C.; Breitkreitz, M.C.; de Paula, E.; Rodrigues da Silva, G.H. Codelivery of Paclitaxel and Cannabidiol in Lipid Nanoparticles Enhances Cytotoxicity against Melanoma Cells. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 21568–21580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapmanee, S.; Bhubhanil, S.; Charoenphon, N.; Inchan, A.; Bunwatcharaphansakun, P.; Khongkow, M.; Namdee, K. Cannabidiol-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles Incorporated in Polyvinyl Alcohol and Sodium Alginate Hydrogel Scaffold for Enhancing Cell Migration and Accelerating Wound Healing. Gels 2024, 10, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybarczyk, A.; Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Piwowarczyk, L.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V. The anti-glioblastoma effects of novel liposomal formulations loaded with cannabidiol, celecoxib, and 2,5 dimethylcelecoxib. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Ravasjani, S.; Zeinali, M.; Asadollahi, L.; Safavi, M.; Mahoutforoush, A.; Talebi, M.; Hamishehkar, H. Hyaluronic Acid-Functionalized Liposomes for Co-delivery of 5-Fluorouracil and Cannabidiol Against Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2025, 15, 43401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Development and Evaluation of Cannabidiol-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Enhanced Oral Bioavailability. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 554. [Google Scholar]

| U-87 MG | U-373 MG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| CBD | 3.7 × 101 (3.4 × 101–4.1 × 101) | 2.8 × 101 (2.6 × 101–3.1 × 101) | 2.8 × 101 (2.2 × 101–3.6 × 101) | 2.7 × 101 (2.6 × 101–2.9 × 101) |

| TMZ | 2.1 × 103 (2 × 103–2.2 × 103) | 1.3 × 103 (8.8 × 102–1.9 × 103) | 1.7 × 103 (7.1 × 102–4.1 × 103) | 8.2 × 102 (7.5 × 102–9.0 × 102) |

| BCNU | 2.1 × 102 (1.6 × 102–4.5 × 102) | 1.7 × 102 (1.5 × 102–2.1 × 102) | 3.1 × 102 (2.6 × 102–3.8 × 102) | 2.7 × 102 (2.2 × 102–3.4 × 102) |

| DOX | 6.1 × 101 (6.1–6.1 × 102) | 3.5 × 10−1 (4.2 × 10−2–1.1) | 6.64 (1.5–2.9 × 101) | 8.9 × 10−1 (2.2 × 10−2–3.5) |

| PTX | 1.5 × 101 (3.1–1.4 × 102) | 5.9 × 10−2 (1.4 × 10−3–9.3 × 10−1) | 2.0 (8.5 × 10−2–4.9 × 102) | 5.2 × 10−2 (1.3 × 10−2–2 × 10−1) |

| Biological Screening | DSC Compatibility | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-87 MG | U-373 MG | |||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |||

| CBD + TMZ | 3.98 ± 3.72 | 9.66 ± 2.46 | 13.76 ± 4.78 | 20.20 ± 3.74 | – | Biologically synergistic Chemically incompatible |

| CBD + BCNU | −2.25 ± 5.42 | −19.10 ± 5.07 | −24.37 ± 4.02 | −9.89 ± 4.23 | – | Biologically antagonistic Chemically incompatible |

| CBD + DOX | −17.03 ± 6.03 | −5.12 ± 3.63 | −3.29 ± 5.53 | −0.21 ± 5.88 | – | Biologically antagonistic Chemically incompatible |

| CBD + PTX | 11.58 ± 5.49 | 6.62 ± 5.49 | 8.08 ± 6.03 | 3.15 ± 3.43 | + | Biologically synergistic No chemical incompatibility detected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez-Lázaro, L.; Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Montejo-Rubio, M.C.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. From Screening to a Nanotechnological Platform: Cannabidiol–Chemotherapy Co-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Glioblastoma Multiforme Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121537

Gómez-Lázaro L, Aparicio-Blanco J, Fraguas-Sánchez AI, Montejo-Rubio MC, Martín-Sabroso C, Torres-Suárez AI. From Screening to a Nanotechnological Platform: Cannabidiol–Chemotherapy Co-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Glioblastoma Multiforme Treatment. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121537

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-Lázaro, Laura, Juan Aparicio-Blanco, Ana Isabel Fraguas-Sánchez, María Consuelo Montejo-Rubio, Cristina Martín-Sabroso, and Ana Isabel Torres-Suárez. 2025. "From Screening to a Nanotechnological Platform: Cannabidiol–Chemotherapy Co-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Glioblastoma Multiforme Treatment" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121537

APA StyleGómez-Lázaro, L., Aparicio-Blanco, J., Fraguas-Sánchez, A. I., Montejo-Rubio, M. C., Martín-Sabroso, C., & Torres-Suárez, A. I. (2025). From Screening to a Nanotechnological Platform: Cannabidiol–Chemotherapy Co-Loaded Lipid Nanocapsules for Glioblastoma Multiforme Treatment. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121537