Design of Polycation-Functionalized Resveratrol Nanocrystals for Intranasal Administration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Preparation of Naked Nanocrystals by Sonoprecipitation Technique

2.4. Particle Size, Polydispersity, and Zeta Potential Analysis

2.5. Naked Nanocrystal Optimization

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Optimized RSV NC

2.7. Polycation–Functionalization of Optimized RSV NC

2.8. Physico-Chemical and Technological Characterization of Naked and Polycation-Functionalized RSV NC

2.8.1. Lyophilization

2.8.2. Drug Content

2.8.3. Saturation Solubility

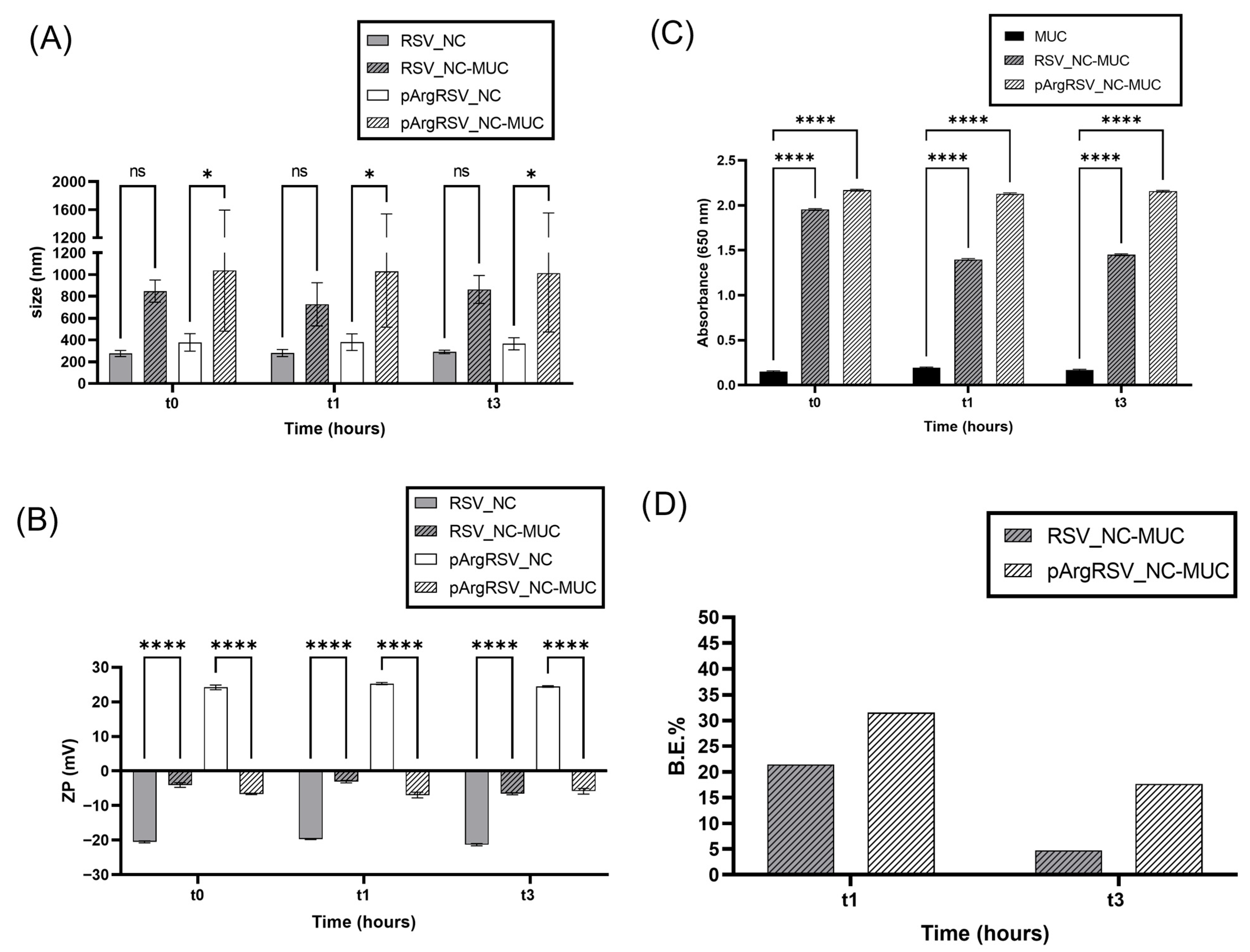

2.8.4. Stability and Interaction of Naked and Surface-Modified Nanosuspensions in the Presence of Nasal Mucus Component

2.8.5. Mucoadhesive Binding

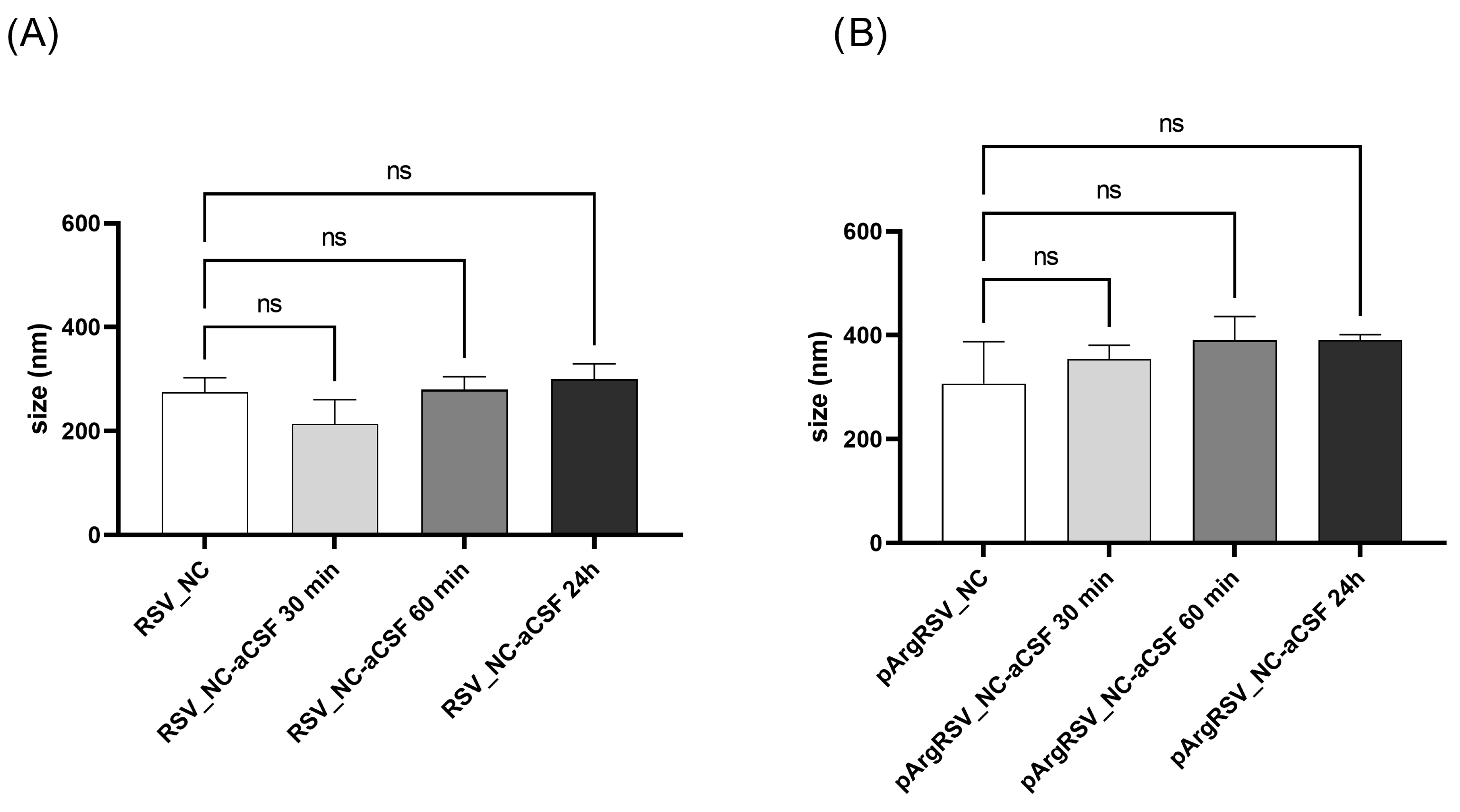

2.8.6. Naked and Polycation-Functionalized RSV NC Behavior in Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid

2.8.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.8.8. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

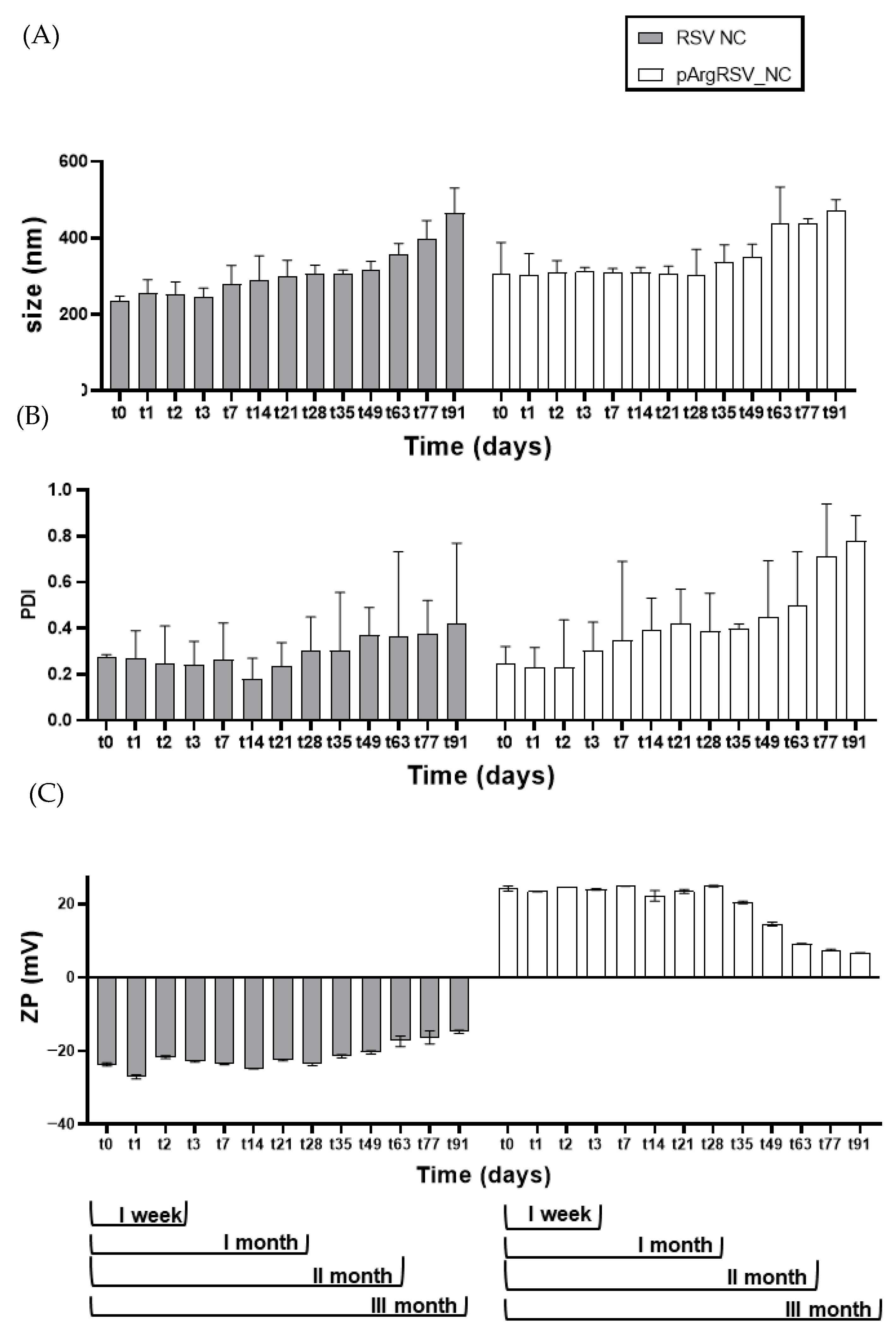

2.8.9. Stability Study

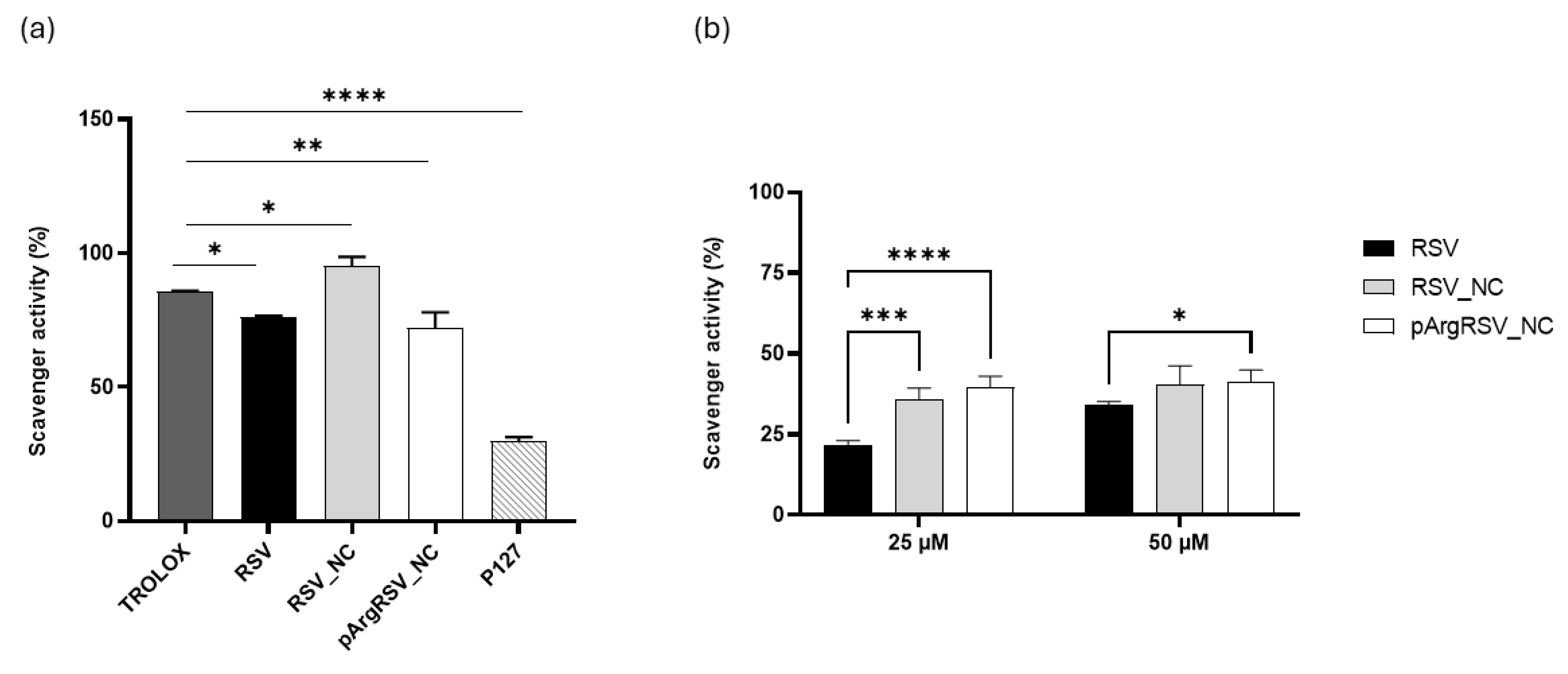

2.8.10. DPPH Assay

2.9. Propagation, Maintenance, and Analysis of Human Microglia (HMC3) Cell Viability

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Knowledge Space and Experimental Domain Construction

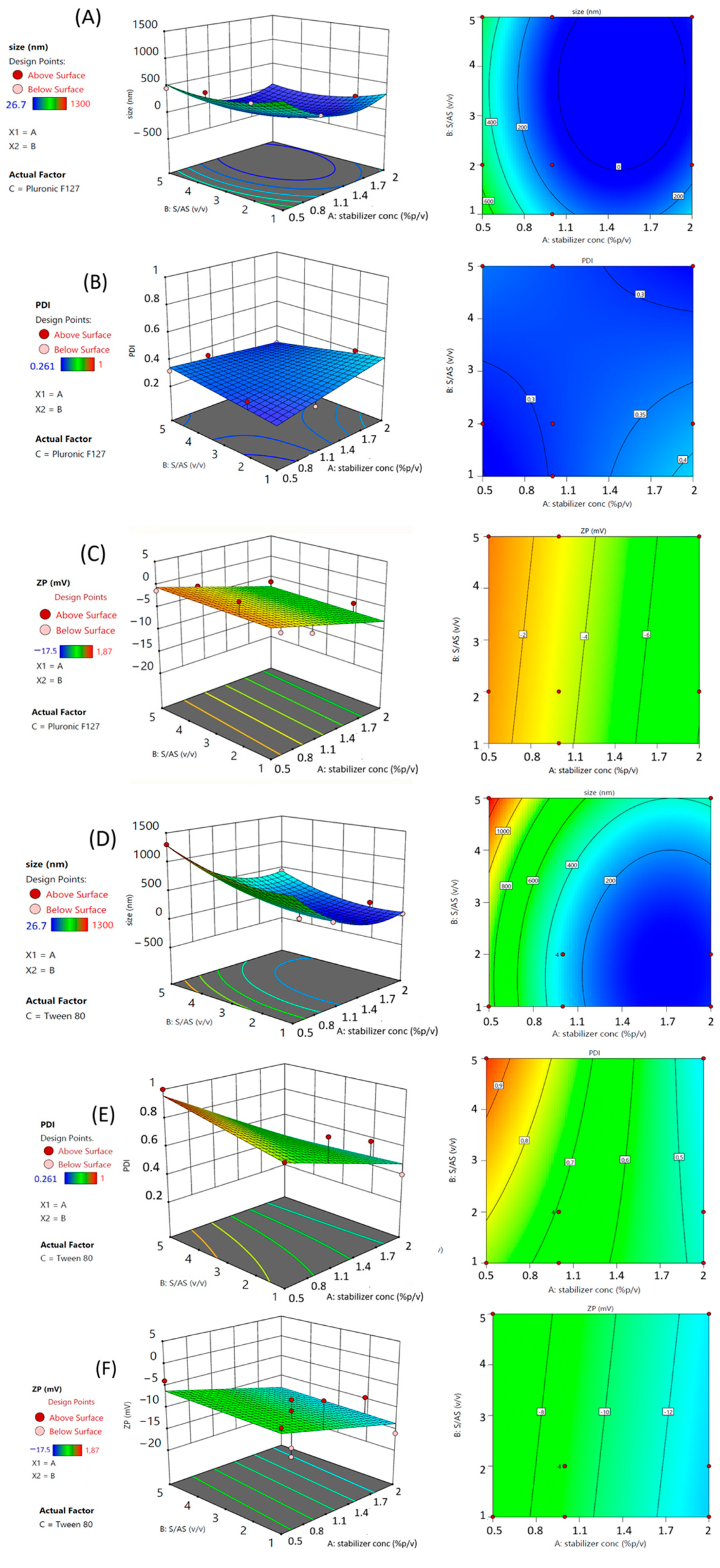

3.1.1. Outcome of Independent Variables for RSV NC Mean Size

3.1.2. Outcome of Independent Variables on RSV NC Polydispersity

3.1.3. Outcome of Independent Variables on RSV NC Zeta Potential

3.2. Preliminary Characterization of Optimized RSV NC

3.3. Technological Characterization of Naked and Surface-Modified RSV Nanosuspensions

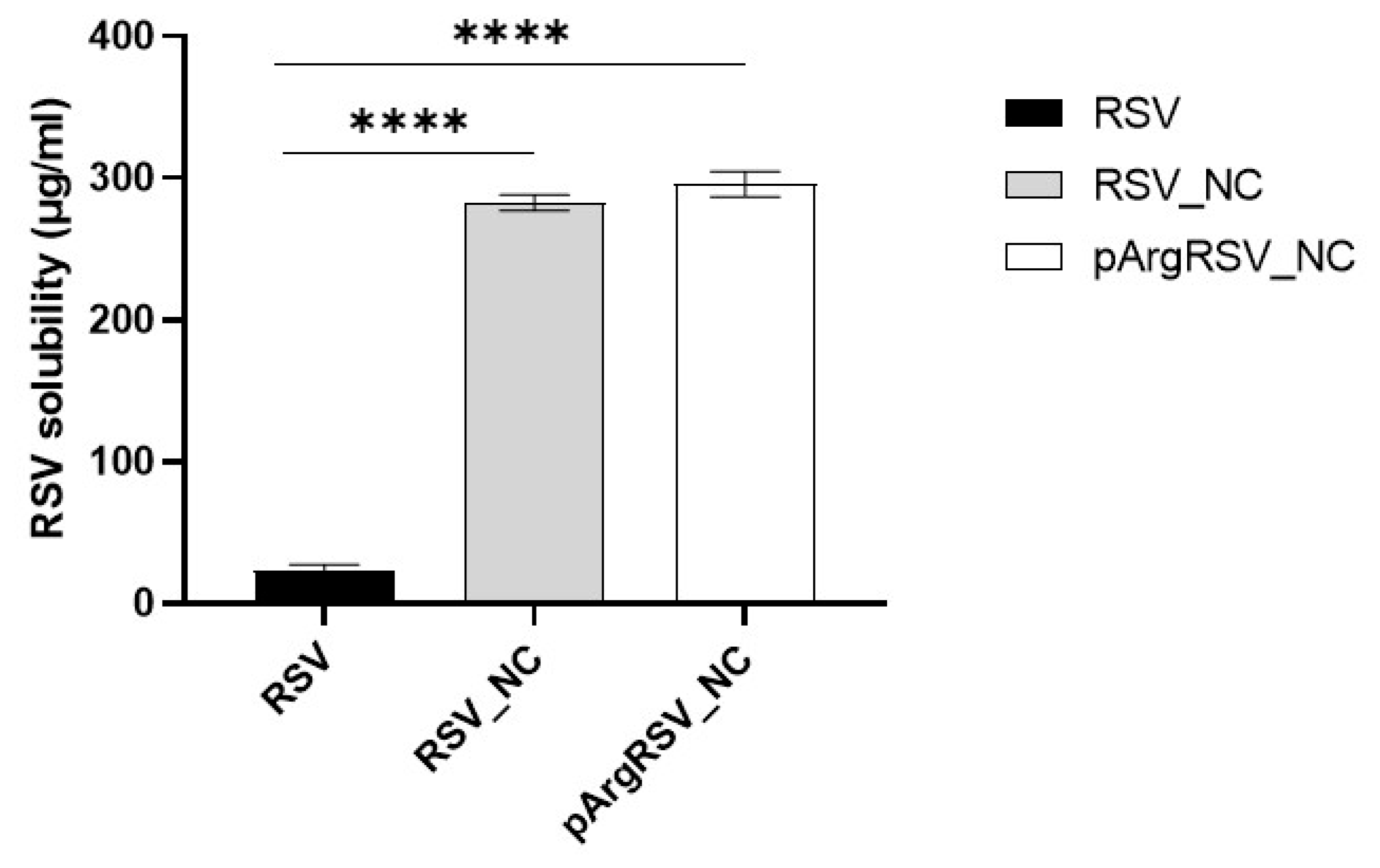

3.3.1. Saturated Solubility and Preliminary Evaluation of Nanosuspension Stability

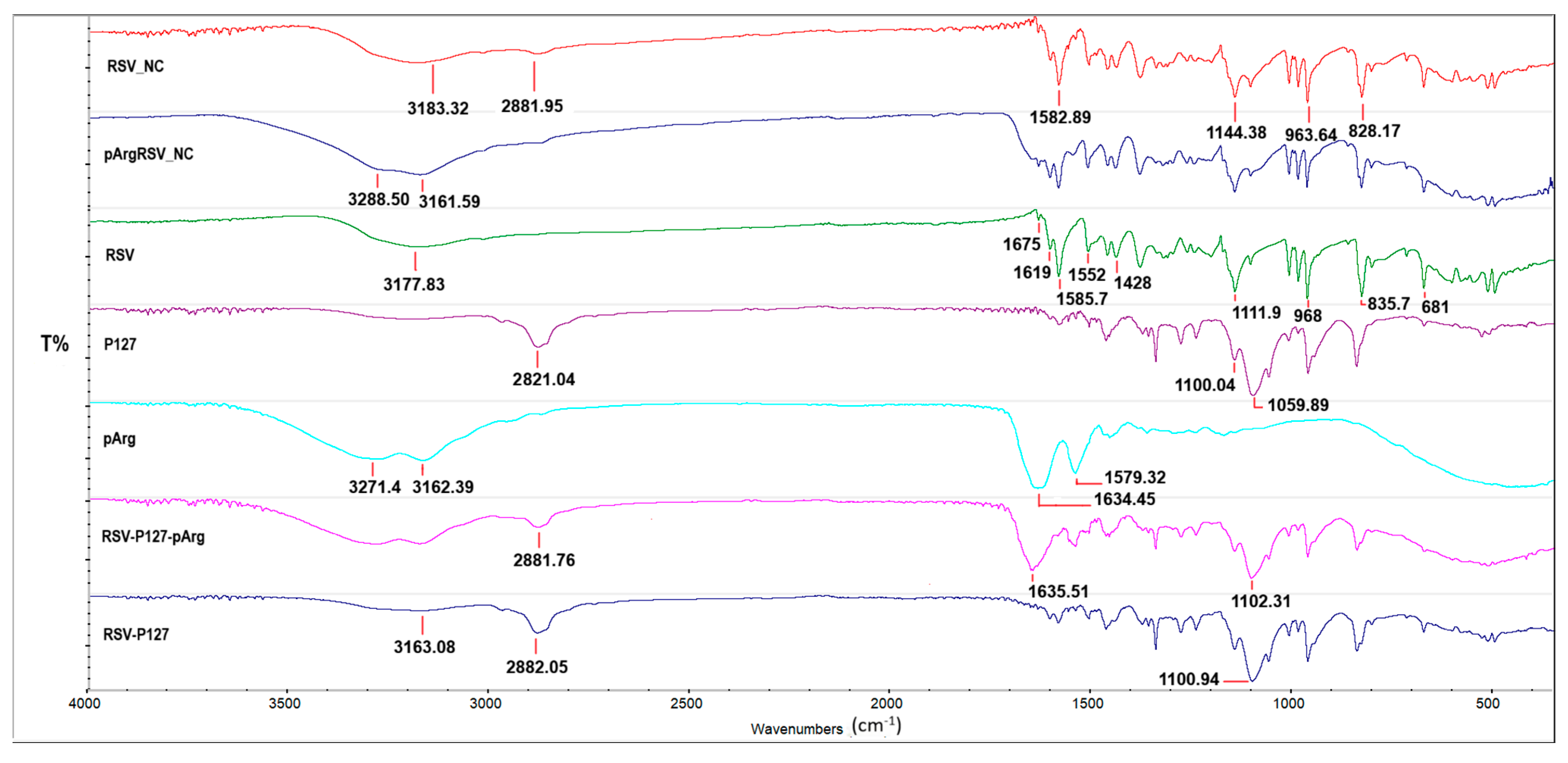

3.3.2. DSC and FTIR Analyses

3.3.3. Mucoadhesive Evaluation

3.3.4. RSV Nanosuspension Behavior in Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid

3.3.5. Radical Scavenging Activity

3.4. Cell Viability Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossier, B.; Jordan, O.; Allémann, E.; Rodríguez-Nogales, C. Nanocrystals and Nanosuspensions: An Exploration from Classic Formulations to Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 3438–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingale, E.; Bonaccorso, A.; Carbone, C.; Musumeci, T.; Pignatello, R. Drug Nanocrystals: Focus on Brain Delivery from Therapeutic to Diagnostic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.; Krishnan, V.; Mitragotri, S. Nanocrystals: A Perspective on Translational Research and Clinical Studies. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Pellitteri, R.; Santonocito, D.; Carbone, C.; Di Martino, P.; Puglisi, G.; Musumeci, T. Optimization of Curcumin Nanocrystals as Promising Strategy for Nose-to-Brain Delivery Application. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Lombardo, R.; Pellitteri, R.; Di Martino, P.; Mancuso, A.; Musumeci, T. Nanonized Carbamazepine for Nose-to-Brain Delivery: Pharmaceutical Formulation Development. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2023, 28, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, T.; Di Benedetto, G.; Carbone, C.; Bonaccorso, A.; Amato, G.; Lo Faro, M.J.; Burgaletto, C.; Puglisi, G.; Bernardini, R.; Cantarella, G. Intranasal Administration of a TRAIL Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody Adsorbed in PLGA Nanoparticles and NLC Nanosystems: An In Vivo Study on a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Musumeci, T.; Serapide, M.F.; Pellitteri, R.; Uchegbu, I.F.; Puglisi, G. Nose to Brain Delivery in Rats: Effect of Surface Charge of Rhodamine B Labeled Nanocarriers on Brain Subregion Localization. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 154, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, T.; Serapide, M.F.; Pellitteri, R.; Dalpiaz, A.; Ferraro, L.; Dal Magro, R.; Bonaccorso, A.; Carbone, C.; Veiga, F.; Sancini, G.; et al. Oxcarbazepine Free or Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles as Effective Intranasal Approach to Control Epileptic Seizures in Rodents. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 133, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, M.; Gupta, V.; Awasthi, R.; Singh, A.; Kulkarni, G.T. Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery: Challenges and Progress towards Brain Targeting in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 86, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drath, I.; Richter, F.; Feja, M. Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery: From Bench to Bedside. Transl. Neurodegener. 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Nagaya, Y.; Hanada, T. Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Interactions of Perampanel and Other Antiepileptic Drugs in a Rat Amygdala Kindling Model. Seizure 2014, 23, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, R.S.; Shriem, L.A.; Al-Nemrawi, N.K. Intranasal Nanocrystals of Tadalafil: In Vitro Characterisation and in Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhaglham, P.; Jiramonai, L.; Jia, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.J.; Zhu, M. Drug Nanocrystals: Surface Engineering and Its Applications in Targeted Delivery. iScience 2024, 27, 111185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiciński, M.; Domanowska, A.; Wódkiewicz, E.; Malinowski, B. Neuroprotective Properties of Resveratrol and Its Derivatives—Influence on Potential Mechanisms Leading to the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Nafady, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Saha, S.; Rashid, S.; Akter, A.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Akhtar, M.F.; Perveen, A.; Ashraf, G.M.; et al. Resveratrol and Neuroprotection: An Insight into Prospective Therapeutic Approaches against Alzheimer’s Disease from Bench to Bedside. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 4384–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.D.; Armas, G.V.; Fernández, M.A.; Grijalvo, S.; Díaz Díaz, D. Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol in Ischemic Brain Injury. NeuroSci 2021, 2, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, V.; Petralia, S.; Vanella, L.; Gulisano, M.; Maugeri, L.; Satriano, C.; Montenegro, L.; Castellano, A.; Sorrenti, V. Innovative Snail-Mucus-Extract (SME)-Coated Nanoparticles Exhibit Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Proliferative Effects for Potential Skin Cancer Prevention and Treatment. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 7655–7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Privitera, A.; Saab, M.W.; Musso, N.; Maugeri, S.; Fidilio, A.; Privitera, A.P.; Pittalà, A.; Jolivet, R.B.; Lanzanò, L.; et al. Characterization of Carnosine Effect on Human Microglial Cells under Basal Conditions. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, S.A.; Anderson, N.G. Design of Experiments (DoE) and Process Optimization. A Review of Recent Publications. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1605–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadžiabdić, J.; Brekalo, S.; Rahić, O.; Tucak, A.; Sirbubalo, M.; Vranić, E. Importance of Stabilizers of Nanocrystals of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Maced. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 66, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, L.C.; Silva-Abreu, M.; Clares, B.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Halbaut, L.; Cañas, M.A.; Calpena, A.C. Formulation Strategies to Improve Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Donepezil. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Mei, D.; Huo, Y.; Mao, S. Effect of Polysorbate 80 on the Intranasal Absorption and Brain Distribution of Tetramethylpyrazine Phosphate in Rats. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Wall, T.; Khoury, G. Optimal Design Generation and Power Evaluation in R: The Skpr Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2021, 99, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Ahmad, S.; Tarabokija, J.; Bilgili, E. Roles of Surfactant and Polymer in Drug Release from Spray-Dried Hybrid Nanocrystal-Amorphous Solid Dispersions (HyNASDs). Powder Technol. 2020, 361, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajera, B.Y.; Shah, D.A.; Dave, R.H. Development of an Amorphous Nanosuspension by Sonoprecipitation-Formulation and Process Optimization Using Design of Experiment Methodology. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 559, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Huang, L.; Liu, F. Understanding the Structure and Stability of Paclitaxel Nanocrystals. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 390, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Carbone, C.; Tomasello, B.; Italiani, P.; Musumeci, T.; Puglisi, G.; Pignatello, R. Optimization of Dextran Sulfate/Poly-L-Lysine Based Nanogels Polyelectrolyte Complex for Intranasal Ovalbumin Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 65, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Zheng, A. Progress in the Development of Stabilization Strategies for Nanocrystal Preparations. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Ghosh, I. Identifying the Correlation between Drug/Stabilizer Properties and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of Nanosuspension Formulation Prepared by Wet Media Milling Technology. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoo, J.Y.; Ahn, C.H. Amphiphilic Amino Acid Copolymers as Stabilizers for the Preparation of Nanocrystal Dispersion. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 24, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque de Castro, M.D.; Priego-Capote, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Crystallization (Sonocrystallization). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007, 14, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenziano, M.; Ansari, I.A.; Muntoni, E.; Spagnolo, R.; Scomparin, A.; Cavalli, R. Lipid-Coated Nanocrystals as a Tool for Improving the Antioxidant Activity of Resveratrol. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Vaidya, Y.; Gulati, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Garg, V.; Pandey, N.K. Nanosuspension: Principles, Perspectives and Practices. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 1222–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Kim, D.T.; Steinman, L.; Fathman, C.G.; Rothbard, J.B.; Rothbard, C.G.; Polyarginine, J.B. Polyarginine Enters Cells More Efficiently than Other Polycationic Homopolymers. J. Pept. Res. 2000, 56, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollo, G.; Gonzalez-Paredes, A.; Garcia-Fuentes, M.; Calvo, P.; Torres, D.; Alonso, M.J. Polyarginine Nanocapsules as a Potential Oral Peptide Delivery Carrier. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, M.; Ling, D.; Hyeon, T.; Talapin, D.V. The Surface Science of Nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.H.; Biriukov, D.; Tempra, C.; Baxova, K.; Martinez-Seara, H.; Evci, H.; Singh, V.; Šachl, R.; Hof, M.; Jungwirth, P.; et al. Ionic Strength and Solution Composition Dictate the Adsorption of Cell-Penetrating Peptides onto Phosphatidylcholine Membranes. Langmuir 2022, 38, 11284–11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingale, E.; Bonaccorso, A.; D’Amico, A.G.; Lombardo, R.; D’Agata, V.; Rautio, J.; Pignatello, R. Formulating Resveratrol and Melatonin Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SNEDDS) for Ocular Administration Using Design of Experiments. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano-Mendez, J.R.; Fabbrocini, G.; De Stefano, D.; Mazzella, C.; Mayol, L.; Scognamiglio, I.; Carnuccio, R.; Ayala, F.; La Rotonda, M.I.; De Rosa, G. Enhanced Antioxidant Effect of Trans-Resveratrol: Potential of Binary Systems with Polyethylene Glycol and Cyclodextrin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2014, 40, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonvico, F.; Clementino, A.; Buttini, F.; Colombo, G.; Pescina, S.; Guterres, S.S.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Nicoli, S. Surface-Modified Nanocarriers for Nose-to-Brain Delivery: From Bioadhesion to Targeting. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwoke, M.I.; Agu, R.U.; Verbeke, N.; Kinget, R. Nasal Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery: Background, Applications, Trends and Future Perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 1640–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.K.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hanes, J. Mucus-Penetrating Nanoparticles for Drug and Gene Delivery to Mucosal Tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnik, A.; Das Neves, J.; Sarmento, B. Mucoadhesive Polymers in the Design of Nano-Drug Delivery Systems for Administration by Non-Parenteral Routes: A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 2030–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, S.; Jones, N.S.; Davis, S.S.; Illum, L. Distribution and Clearance of Bioadhesive Formulations from the Olfactory Region in Man: Effect of Polymer Type and Nasal Delivery Device. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 30, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvát, S.; Fehér, A.; Wolburg, H.; Sipos, P.; Veszelka, S.; Tóth, A.; Kis, L.; Kurunczi, A.; Balogh, G.; Kürti, L.; et al. Sodium Hyaluronate as a Mucoadhesive Component in Nasal Formulation Enhances Delivery of Molecules to Brain Tissue. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 72, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ye, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Xia, X.; Liu, Y. Comparative Study of Mucoadhesive and Mucus-Penetrative Nanoparticles Based on Phospholipid Complex to Overcome the Mucus Barrier for Inhaled Delivery of Baicalein. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sharma, R.K.; Sharma, N.; Gabrani, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Ali, J.; Dang, S. Nose-To-Brain Delivery of PLGA-Diazepam Nanoparticles. AAPS PharmSciTech 2015, 16, 1108–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sharma, R.K.; Bhatnagar, A.; Nishad, D.K.; Singh, T.; Gabrani, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Ali, J.; Dang, S. Nose to Brain Delivery of Midazolam Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles: In Vitro and In Vivo Investigations. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirimer, L.; Zhang, Q.; Kuang, S.; Cheung, C.W.J.; Chu, K.A.; He, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhao, X. Engineering Three-Dimensional Microenvironments towards in Vitro Disease Models of the Central Nervous System. Biofabrication 2019, 11, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, C.; Toghani, D.; Wong, B.; Nance, E. Colloidal Stability as a Determinant of Nanoparticle Behavior in the Brain. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubori, A.; Sulaiman, G.; Tawfeeq, A. Antioxidant Activities of Resveratrol Loaded Poloxamer 407: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. J. Appl. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2021, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasowska, A.; Lukaszewicz, M. Antioxidant Activity of BHT and New Phenolic Compounds PYA, PPA Measured by Chemiluminescence Method. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2001, 6, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsson, B. Stability-Indicating Changes in Poloxamers: The Degradation of Ethylene Oxide-Propylene Oxide Block Copolymers at 25 and 40 °C. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 78, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádasi, A.; Maruniaková, N.; Štochmaľová, A.; Bauer, M.; Grossmann, R.; Harrath, A.H.; Kolesárová, A.; Sirotkin, A.V. Direct Effect of Curcumin on Porcine Ovarian Cell Functions. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 182, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Wang, J.J.; Cai, Z.N.; Xu, C.J. The Effect of Curcumin on the Differentiation, Apoptosis and Cell Cycle of Neural Stem Cells Is Mediated through Inhibiting Autophagy by the Modulation of Atg7 and P62. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2481–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol Ameliorates Aging-Related Metabolic Phenotypes by Inhibiting CAMP Phosphodiesterases. Cell 2012, 148, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybakova, Y.S.; Boldyrev, A.A. Effect of Carnosine and Related Compounds on Proliferation of Cultured Rat Pheochromocytoma PC-12 Cells. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012, 154, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnyakova, K.S.; Babizhayev, M.A.; Aliper, A.M.; Buzdin, A.A.; Kudryavzeva, A.V.; Yegorov, Y.E. Stimulation of Cell Proliferation by Carnosine: Cell and Transcriptome Approaches. Mol. Biol. 2014, 48, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, W.; Liu, T.; Mosenthin, R.; Bao, Y.; Chen, P.; Hao, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Ji, C.; et al. Improved Satellite Cell Proliferation Induced by L-Carnosine Benefits Muscle Growth of Pigs in Part through Activation of the Akt/MTOR/S6K Signaling Pathway. Agriculture 2022, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Francis, N.L.; Calvelli, H.R.; Moghe, P.V. Microglia-Targeting Nanotherapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. APL Bioeng. 2020, 4, 030902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.S.; Zheng, W.H.; Bastianetto, S.; Chabot, J.G.; Quirion, R. Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol against β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rat Hippocampal Neurons: Involvement of Protein Kinase C. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 141, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Independent Variables | Type | Coded Factors | Polynomial Term | Levels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Stabilizer conc. (%w/v) | numeric | X1 | A | 0.5 | 2 |

| S/AS ratio (v/v) | numeric | X2 | B | 1:1 | 1:5 |

| Stabilizer type | categoric | X3 | C | Pluronic® F127 Tween® 80 | |

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Mean size (nm) | Y1 | ||||

| PDI | Y2 | ||||

| ZP (mV) | Y3 | ||||

| RSV NC Composition | Optimized RSV NC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabilizer | S/AS Ratio (v/v) | Mean Size (nm ± SD) | PDI ± SD | ZP (mV ± SD) | |

| Conc. (% w/v) | Type | ||||

| 0.7 | P127 | 1:2 | 245.2 ± 27.6 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | −23.7 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonaccorso, A.; Zingale, E.; Caruso, G.; Privitera, A.; Carbone, C.; Lo Faro, M.J.; Caraci, F.; Musumeci, T.; Pignatello, R. Design of Polycation-Functionalized Resveratrol Nanocrystals for Intranasal Administration. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101346

Bonaccorso A, Zingale E, Caruso G, Privitera A, Carbone C, Lo Faro MJ, Caraci F, Musumeci T, Pignatello R. Design of Polycation-Functionalized Resveratrol Nanocrystals for Intranasal Administration. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(10):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101346

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonaccorso, Angela, Elide Zingale, Giuseppe Caruso, Anna Privitera, Claudia Carbone, Maria Josè Lo Faro, Filippo Caraci, Teresa Musumeci, and Rosario Pignatello. 2025. "Design of Polycation-Functionalized Resveratrol Nanocrystals for Intranasal Administration" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 10: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101346

APA StyleBonaccorso, A., Zingale, E., Caruso, G., Privitera, A., Carbone, C., Lo Faro, M. J., Caraci, F., Musumeci, T., & Pignatello, R. (2025). Design of Polycation-Functionalized Resveratrol Nanocrystals for Intranasal Administration. Pharmaceutics, 17(10), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101346