Targeting Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) for Cancer Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

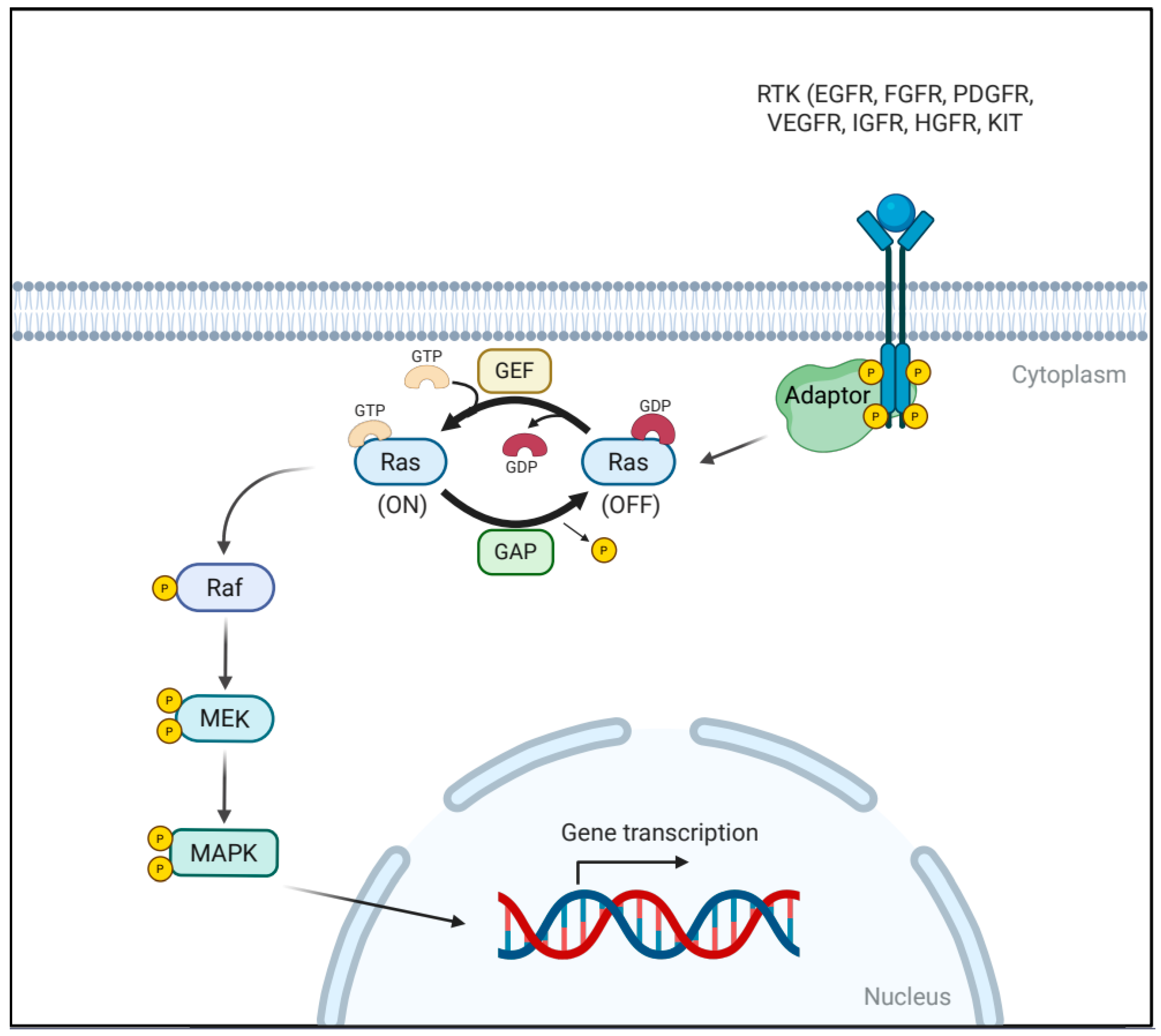

2. The RAS/MAPK Signaling Pathway

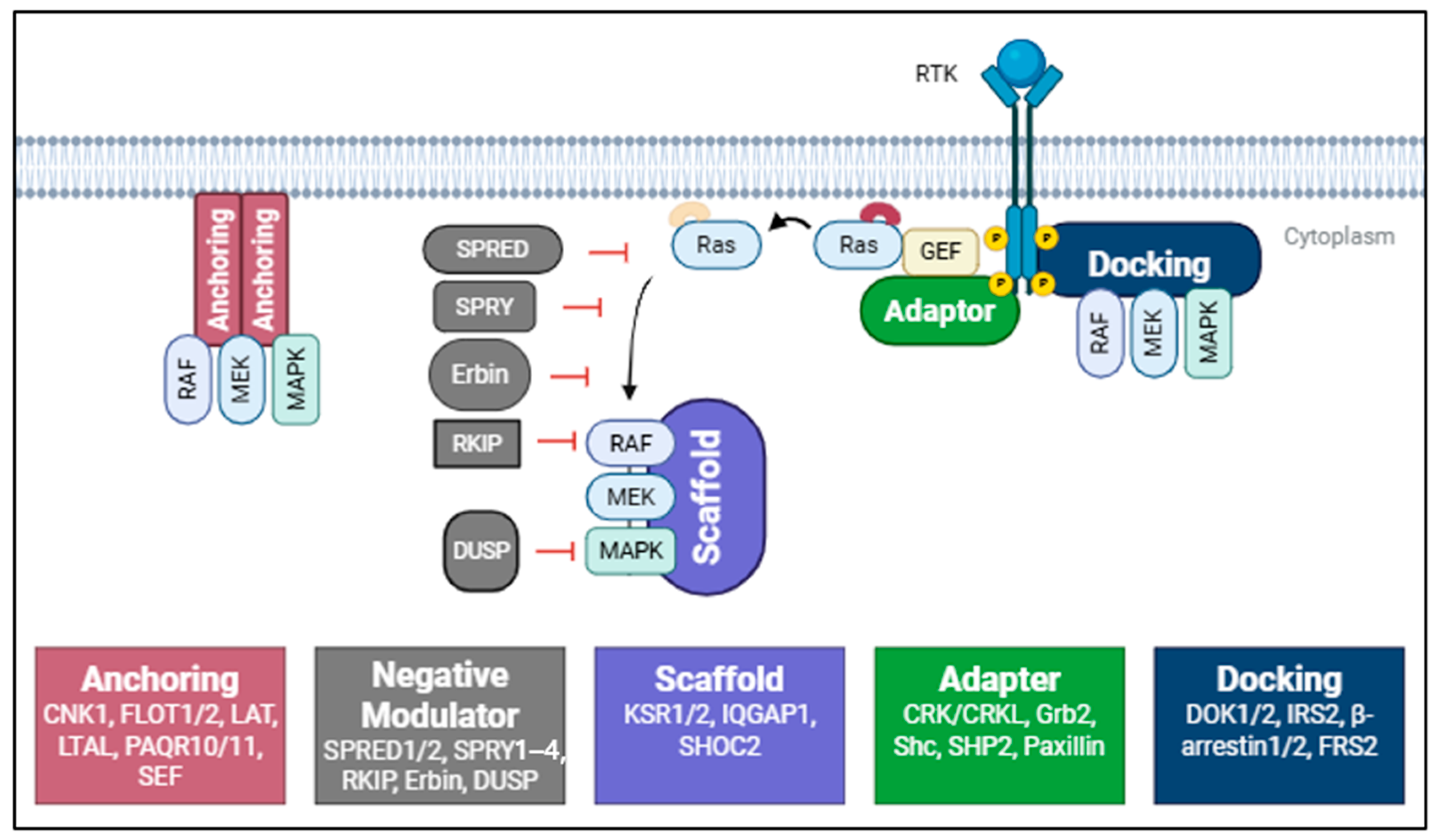

3. Accessory and Scaffold Proteins in the RAS/MAPK Signaling Pathway

3.1. Anchoring Proteins: Spatial Regulation of Kinase Activity

3.2. Docking Proteins: Bridging Receptors and Signaling Modules

3.3. Adaptor Proteins: Signal Integration and Branching

3.4. Scaffold Proteins: Assembling and Modulating the MAPK Module

3.5. Negative Modulators of RAS/MAPK Signaling

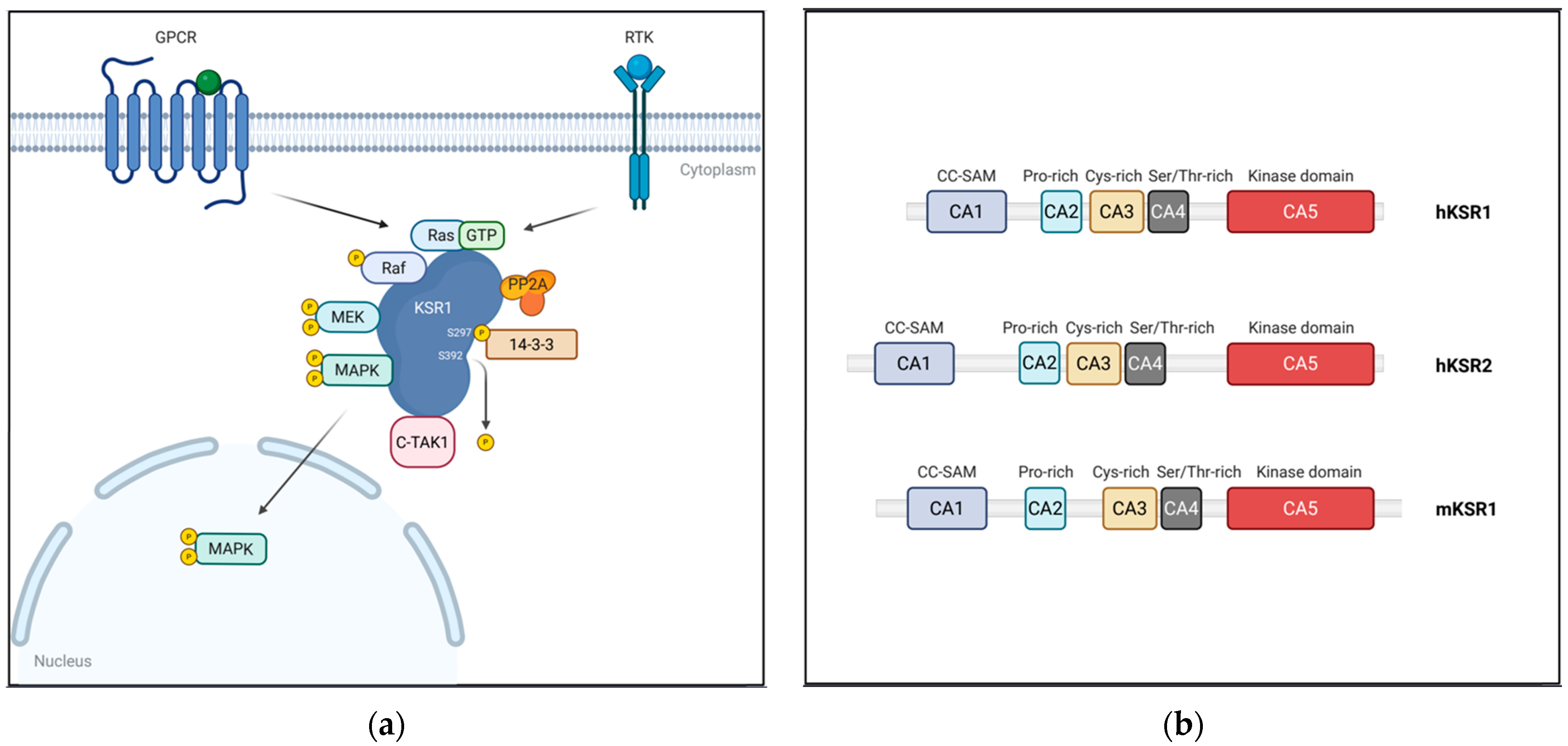

4. KSR: A Central Scaffold in RAS/MAPK Signaling

4.1. Structure of KSR Proteins

4.1.1. CA1 (Coiled-Coil/SAM Domain)

4.1.2. CA2 (Proline-Rich Domain)

4.1.3. CA3 (Atypical C1 Domain)

4.1.4. CA4 (Serine/Threonine-Rich Domain)

4.1.5. CA5 (Kinase/Pseudokinase Domain)

4.2. Dynamic Regulation of KSR1 Localization

4.3. Beyond Scaffolding: Alternative Functions of KSR1 in RAS/MAPK Signaling

5. Roles of KSR1 in Cancer

5.1. KSR1 as a Tumor-Promoter

5.2. KSR as a Tumor-Suppressor

6. Targeting KSR1

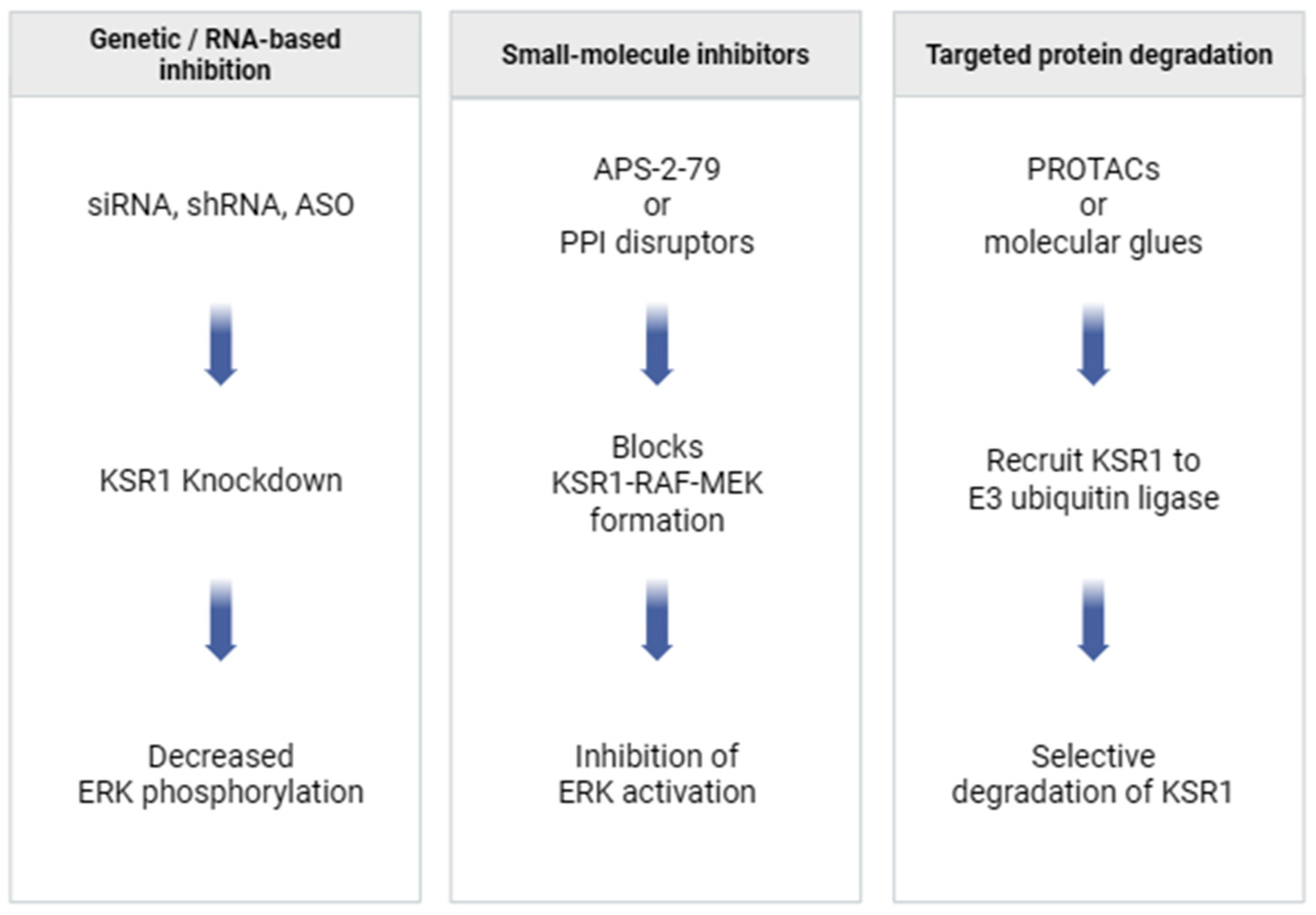

6.1. Preclinical Studies Targeting KSR1

6.2. Potential Strategies for KSR1 Targeting

6.2.1. Small-Molecule Disruptors of KSR1–RAF/MEK Interactions

6.2.2. Targeted Protein Degradation Approaches

6.2.3. RNA-Based Silencing Methods

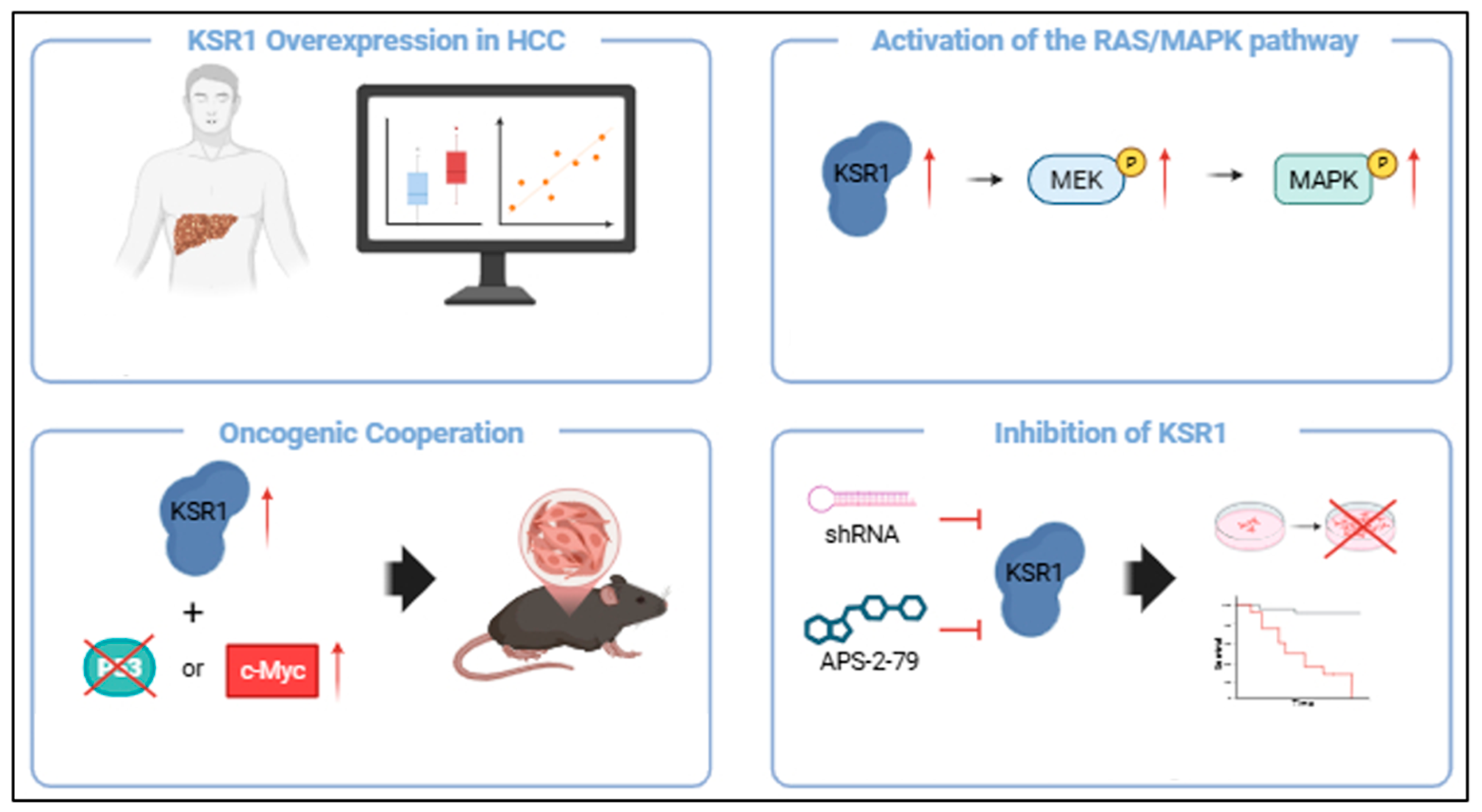

7. Targeting KSR1 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

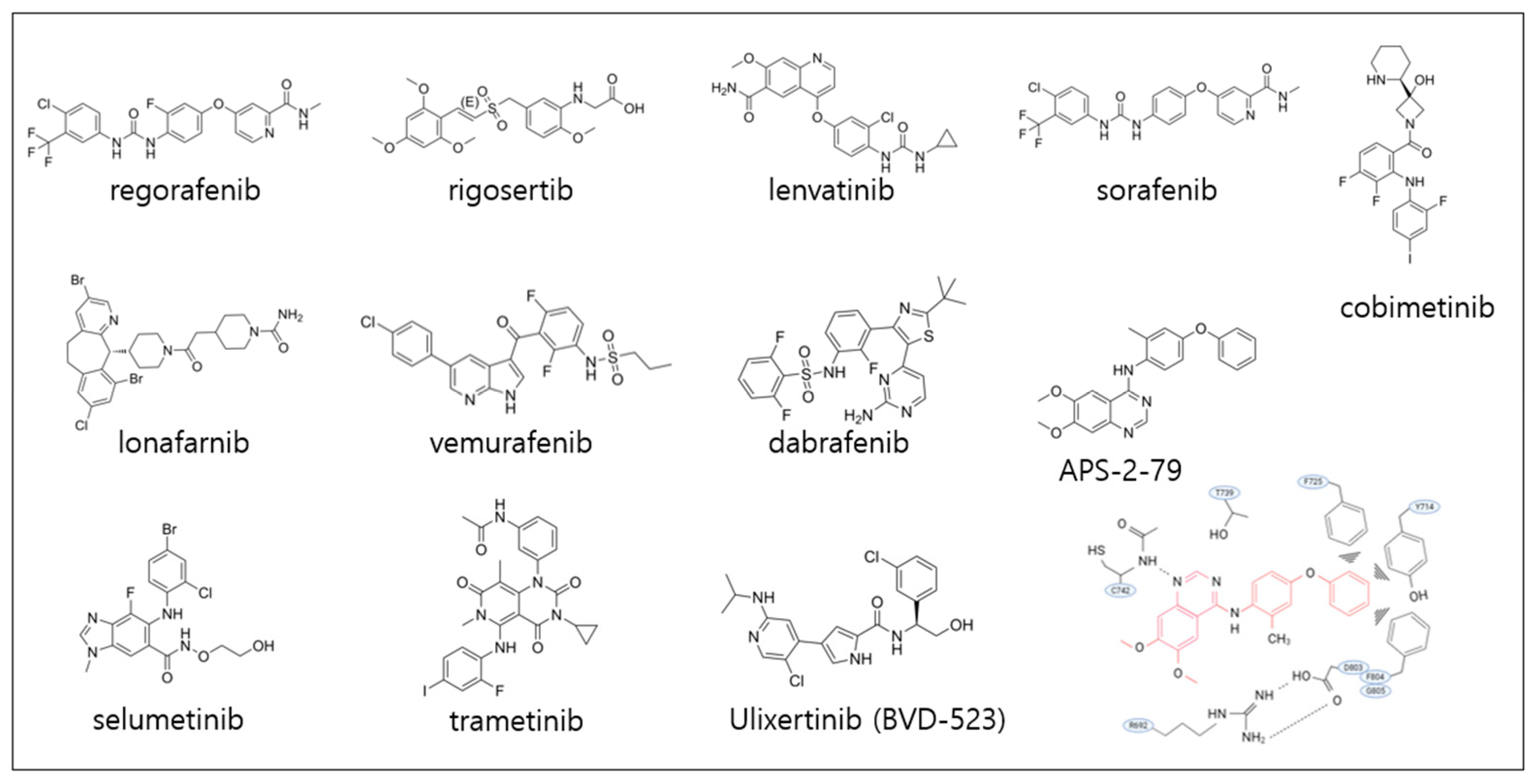

7.1. Preclinical Studies Targeting RAS/MAPK Signaling in HCC

7.2. Resistance to Drugs Targeting the RAS/MAPK Signaling Pathway in HCC

7.3. KSR as a Therapeutic Target in HCC

7.4. Clinical Studies Targeting Other Dysregulated Elements of the RAS/MAPK Pathway

8. Perspectives and Conclusions

8.1. Targeting KSR1 in HCC

8.2. Future Research Directions

8.3. Combination Therapies as Possible Therapeutic Strategies

8.3.1. Combination with MEK or ERK Inhibitors

8.3.2. Combination with Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) Inhibitors

8.3.3. Combination with Immunotherapies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, X.; Yi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Lin, D.; Wu, C. Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis: Molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; He, C.; Wang, M.; Ma, X.; Mo, F.; Yang, S.; Han, J.; Wei, X. Targeting epigenetic regulators for cancer therapy: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herceg, Z.; Hainaut, P. Genetic and epigenetic alterations as biomarkers for cancer detection, diagnosis and prognosis. Mol. Oncol. 2007, 1, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: From mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Perry, M.A.; Chou, J.F.; Nandakumar, S.; Muldoon, D.; Erakky, A.; Zucker, A.; Fong, C.; Mehine, M.; Nguyen, B.; et al. Clinicogenomic landscape of pancreatic adenocarcinoma identifies KRAS mutant dosage as prognostic of overall survival. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, Q.; Zou, C.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y. Application and recent advances in conventional biomarkers for the prognosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1598934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yang, X.; Geng, M.; Huang, M. Targeting ERK, an Achilles’ Heel of the MAPK pathway, in cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, M.; Barbacid, M. Targeting the MAPK Pathway in KRAS-Driven Tumors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, Y.A.; Bracho, R.P.; Chauhan, S.C.; Tripathi, M.K.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Small Molecule B-RAF Inhibitors as Anti-Cancer Therapeutics: Advances in Discovery, Development, and Mechanistic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubatka, P.; Bojkova, B.; Nosalova, N.; Huniadi, M.; Samuel, S.M.; Sreenesh, B.; Hrklova, G.; Kajo, K.; Hornak, S.; Cizkova, D.; et al. Targeting the MAPK signaling pathway: Implications and prospects of flavonoids in 3P medicine as modulators of cancer cell plasticity and therapeutic resistance in breast cancer patients. Epma J. 2025, 16, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Horimoto, M.; Wada, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Kasahara, A.; Ueki, T.; Hirano, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Fujimoto, J.; et al. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1998, 27, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delire, B.; Stärkel, P. The Ras/MAPK pathway and hepatocarcinoma: Pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 45, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardin, P.; Camonis, J.H.; Gale, N.W.; van Aelst, L.; Schlessinger, J.; Wigler, M.H.; Bar-Sagi, D. Human Sos1: A guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras that binds to GRB2. Science 1993, 260, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, C.; Stainthorp, A.K.; Ketchen, S.; Jones, C.M.; Marks, K.; Quirke, P.; Ladbury, J.E. The Grb2 splice variant, Grb3-3, is a negative regulator of RAS activation. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, M.; Satyanarayana, A. Molecular Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targets in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cseh, B.; Doma, E.; Baccarini, M. “RAF” neighborhood: Protein-protein interaction in the Raf/Mek/Erk pathway. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.S.; Hagan, S.; Rath, O.; Kolch, W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3279–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maik-Rachline, G.; Hacohen-Lev-Ran, A.; Seger, R. Nuclear ERK: Mechanism of Translocation, Substrates, and Role in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudewell, S.; Wittich, C.; Kazemein Jasemi, N.S.; Bazgir, F.; Ahmadian, M.R. Accessory proteins of the RAS-MAPK pathway: Moving from the side line to the front line. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Vega, A.; Cobb, M.H. Navigating the ERK1/2 MAPK Cascade. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Mühlhäuser, W.W.D.; Warscheid, B.; Radziwill, G. Membrane localization of acetylated CNK1 mediates a positive feedback on RAF/ERK signaling. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Ye, M.; Jin, X. The roles of FLOT1 in human diseases (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña-Villa, A.K.; Lara-Lemus, R. The Structural Proteins of Membrane Rafts, Caveolins and Flotillins, in Lung Cancer: More Than Just Scaffold Elements. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomé, C.H.; Ferreira, G.A.; Pereira-Martins, D.A.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Ortiz, C.A.; de Souza, L.E.B.; Sobral, L.M.; Silva, C.L.A.; Scheucher, P.S.; Gil, C.D.; et al. NTAL is associated with treatment outcome, cell proliferation and differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Ding, Q.; Huang, H.; Xu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; He, J.; Liu, W.; et al. PAQR10 and PAQR11 mediate Ras signaling in the Golgi apparatus. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.D.; Sacks, D.B. Protein scaffolds in MAP kinase signalling. Cell. Signal. 2009, 21, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, M.R. Sef: A MEK/ERK catcher on the Golgi. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M. A new role for Dok. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R. Insulin signaling in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e142241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Neto, C.M.; Parreiras, E.S.L.T. Deciphering complexity of GPCR signaling and modulation: Implications and perspectives for drug discovery. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsai, A.W.; Shah, K.S.; Shim, P.J.; Lee, M.A.; Shreiber, B.N.; Schwalb, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Kwon, H.Y.; Huang, L.Y.; Soderblom, E.J.; et al. Signal transduction at GPCRs: Allosteric activation of the ERK MAPK by β-arrestin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303794120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Su, N.; Yang, J.; Tan, Q.; Huang, S.; Jin, M.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Luo, F.; et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, T. Dynamic control of signaling by modular adaptor proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeno-Nakazawa, Y.; Kasai, T.; Ki, S.; Kostyanovskaya, E.; Pawlak, J.; Yamagishi, J.; Okimoto, N.; Taiji, M.; Okada, M.; Westbrook, J.; et al. A pre-metazoan origin of the CRK gene family and co-opted signaling network. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagrinò, F.; Puglisi, E.; Pagano, L.; Travaglini-Allocatelli, C.; Toto, A. GRB2: A dynamic adaptor protein orchestrating cellular signaling in health and disease. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemein Jasemi, N.S.; Herrmann, C.; Magdalena Estirado, E.; Gremer, L.; Willbold, D.; Brunsveld, L.; Dvorsky, R.; Ahmadian, M.R. The intramolecular allostery of GRB2 governing its interaction with SOS1 is modulated by phosphotyrosine ligands. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 2793–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemein Jasemi, N.S.; Ahmadian, M.R. Allosteric regulation of GRB2 modulates RAS activation. Small GTPases 2022, 13, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.B.M.; Prigent, S.A. Insights into the Shc Family of Adaptor Proteins. J. Mol. Signal 2017, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Libring, S.; Ruddraraju, K.V.; Miao, J.; Solorio, L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wendt, M.K. SHP2 is a multifunctional therapeutic target in drug resistant metastatic breast cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 7166–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.D. Paxillin: A focal adhesion-associated adaptor protein. Oncogene 2001, 20, 6459–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, F.; Laberge, G.; Douziech, M.; Ferland-McCollough, D.; Therrien, M. KSR is a scaffold required for activation of the ERK/MAPK module. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frodyma, D.; Neilsen, B.; Costanzo-Garvey, D.; Fisher, K.; Lewis, R. Coordinating ERK signaling via the molecular scaffold Kinase Suppressor of Ras. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, S.; Zhou, M.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Morrison, D.K. Protein phosphatase 2A positively regulates Ras signaling by dephosphorylating KSR1 and Raf-1 on critical 14-3-3 binding sites. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thines, L.; Roushar, F.J.; Hedman, A.C.; Sacks, D.B. The IQGAP scaffolds: Critical nodes bridging receptor activation to cellular signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202205062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Stevens, P.; Gao, T.; Galperin, E. The leucine-rich repeat signaling scaffolds Shoc2 and Erbin: Cellular mechanism and role in disease. Febs J. 2021, 288, 721–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, F.; Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Sun, W.; Liang, S.; Zhai, Z.; Jiang, Z. PCBP2 mediates degradation of the adaptor MAVS via the HECT ubiquitin ligase AIP4. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, C.; McCormick, F. SPRED proteins and their roles in signal transduction, development, and malignancy. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawazoe, T.; Taniguchi, K. The Sprouty/Spred family as tumor suppressors: Coming of age. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, N.; Jung, H.; Song, M. SPROUTY2, a Negative Feedback Regulator of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling, Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touboul, R.; Baritaki, S.; Zaravinos, A.; Bonavida, B. RKIP Pleiotropic Activities in Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases: Role in Immunity. Cancers 2021, 13, 6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, K.; Lohse, M.J.; Quitterer, U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature 2003, 426, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Peela, S.; Bramhachari, P.V.; Mallikarjuna, K.; Nagaraju, G.P.; Srilatha, M. Raf-kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP): A therapeutic target in colon cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.H.; Ahmed, M.; Hwang, J.S.; Bahar, M.E.; Pham, T.M.; Yang, J.; Kim, W.; Maulidi, R.F.; Lee, D.K.; Kim, D.H.; et al. Manipulating RKIP reverses the metastatic potential of breast cancer cells. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1189350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cessna, H.; Baritaki, S.; Zaravinos, A.; Bonavida, B. The Role of RKIP in the Regulation of EMT in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2022, 14, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figy, C.; Guo, A.; Fernando, V.R.; Furuta, S.; Al-Mulla, F.; Yeung, K.C. Changes in Expression of Tumor Suppressor Gene RKIP Impact How Cancers Interact with Their Complex Environment. Cancers 2023, 15, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Zang, M.; Xiong, W.C.; Luo, Z.; Mei, L. Erbin suppresses the MAP kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoubai, F.Z.; Grosset, C.F. DUSP9, a Dual-Specificity Phosphatase with a Key Role in Cell Biology and Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Chuang, H.C.; Tan, T.H. Regulation of Dual-Specificity Phosphatase (DUSP) Ubiquitination and Protein Stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.K.; Abdollah, N.A.; Shafie, N.H.; Yusof, N.M.; Razak, S.R.A. Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6): A review of its molecular characteristics and clinical relevance in cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2018, 15, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Song, M.; Jiao, R.; Li, W.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, M.; Jin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, H. DUSP7 inhibits cervical cancer progression by inactivating the RAS pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 9306–9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melillo, R.M.; Santoro, M.; Ong, S.H.; Billaud, M.; Fusco, A.; Hadari, Y.R.; Schlessinger, J.; Lax, I. Docking protein FRS2 links the protein tyrosine kinase RET and its oncogenic forms with the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 4177–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornfeld, K.; Hom, D.B.; Horvitz, H.R. The ksr-1 gene encodes a novel protein kinase involved in Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans. Cell 1995, 83, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, M.; Han, M. The C. elegans ksr-1 gene encodes a novel Raf-related kinase involved in Ras-mediated signal transduction. Cell 1995, 83, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.C.; Hartig, N.; Boned Del Río, I.; Sari, S.; Ringham-Terry, B.; Wainwright, J.R.; Jones, G.G.; McCormick, F.; Rodriguez-Viciana, P. SHOC2-MRAS-PP1 complex positively regulates RAF activity and contributes to Noonan syndrome pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10576–E10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauseman, Z.J.; Fodor, M.; Dhembi, A.; Viscomi, J.; Egli, D.; Bleu, M.; Katz, S.; Park, E.; Jang, D.M.; Porter, K.A.; et al. Structure of the MRAS-SHOC2-PP1C phosphatase complex. Nature 2022, 609, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boned Del Río, I.; Young, L.C.; Sari, S.; Jones, G.G.; Ringham-Terry, B.; Hartig, N.; Rejnowicz, E.; Lei, W.; Bhamra, A.; Surinova, S.; et al. SHOC2 complex-driven RAF dimerization selectively contributes to ERK pathway dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13330–13339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilsen, B.K.; Frodyma, D.E.; Lewis, R.E.; Fisher, K.W. KSR as a therapeutic target for Ras-dependent cancers. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koveal, D.; Schuh-Nuhfer, N.; Ritt, D.; Page, R.; Morrison, D.K.; Peti, W. A CC-SAM, for coiled coil-sterile α motif, domain targets the scaffold KSR-1 to specific sites in the plasma membrane. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolch, W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo-Garvey, D.L.; Pfluger, P.T.; Dougherty, M.K.; Stock, J.L.; Boehm, M.; Chaika, O.; Fernandez, M.R.; Fisher, K.; Kortum, R.L.; Hong, E.G.; et al. KSR2 is an essential regulator of AMP kinase, energy expenditure, and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Horita, D.A.; Waugh, D.S.; Byrd, R.A.; Morrison, D.K. Solution structure and functional analysis of the cysteine-rich C1 domain of kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR). J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 315, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, A.M.; Michaud, N.R.; Therrien, M.; Mathes, K.; Copeland, T.; Rubin, G.M.; Morrison, D.K. Identification of constitutive and ras-inducible phosphorylation sites of KSR: Implications for 14-3-3 binding, mitogen-activated protein kinase binding, and KSR overexpression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavoie, H.; Sahmi, M.; Maisonneuve, P.; Marullo, S.A.; Thevakumaran, N.; Jin, T.; Kurinov, I.; Sicheri, F.; Therrien, M. MEK drives BRAF activation through allosteric control of KSR proteins. Nature 2018, 554, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortum, R.L.; Lewis, R.E. The molecular scaffold KSR1 regulates the proliferative and oncogenic potential of cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 4407–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Koo, C.Y.; Stebbing, J.; Giamas, G. The dual function of KSR1: A pseudokinase and beyond. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razidlo, G.L.; Kortum, R.L.; Haferbier, J.L.; Lewis, R.E. Phosphorylation regulates KSR1 stability, ERK activation, and cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47808–47814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniagua, G.; Jacob, H.K.C.; Brehey, O.; García-Alonso, S.; Lechuga, C.G.; Pons, T.; Musteanu, M.; Guerra, C.; Drosten, M.; Barbacid, M. KSR induces RAS-independent MAPK pathway activation and modulates the efficacy of KRAS inhibitors. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 3066–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.W.; Das, B.; Kim, H.S.; Clymer, B.K.; Gehring, D.; Smith, D.R.; Costanzo-Garvey, D.L.; Fernandez, M.R.; Brattain, M.G.; Kelly, D.L.; et al. AMPK Promotes Aberrant PGC1β Expression to Support Human Colon Tumor Cell Survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 3866–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germino, E.A.; Miller, J.P.; Diehl, L.; Swanson, C.J.; Durinck, S.; Modrusan, Z.; Miner, J.H.; Shaw, A.S. Homozygous KSR1 deletion attenuates morbidity but does not prevent tumor development in a mouse model of RAS-driven pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramling, M.W.; Eischen, C.M. Suppression of Ras/Mapk pathway signaling inhibits Myc-induced lymphomagenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Krstic, A.; Neve, A.; Casalou, C.; Rauch, N.; Wynne, K.; Cassidy, H.; McCann, A.; Kavanagh, E.; McCann, B.; et al. Kinase Suppressor of RAS 1 (KSR1) Maintains the Transformed Phenotype of BRAFV600E Mutant Human Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, J.; Xing, R.; Cai, Z.; Jensen, H.L.; Trempus, C.; Mark, W.; Cannon, R.; Kolesnick, R. Deficiency of kinase suppressor of Ras1 prevents oncogenic ras signaling in mice. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 4232–4238. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.; Burack, W.R.; Stock, J.L.; Kortum, R.; Chaika, O.V.; Afkarian, M.; Muller, W.J.; Murphy, K.M.; Morrison, D.K.; Lewis, R.E.; et al. Kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR) is a scaffold which facilitates mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 3035–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denouel-Galy, A.; Douville, E.M.; Warne, P.H.; Papin, C.; Laugier, D.; Calothy, G.; Downward, J.; Eychène, A. Murine Ksr interacts with MEK and inhibits Ras-induced transformation. Curr. Biol. 1998, 8, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joneson, T.; Fulton, J.A.; Volle, D.J.; Chaika, O.V.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Lewis, R.E. Kinase suppressor of Ras inhibits the activation of extracellular ligand-regulated (ERK) mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase by growth factors, activated Ras, and Ras effectors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 7743–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.; Michaud, N.R.; Rubin, G.M.; Morrison, D.K. KSR modulates signal propagation within the MAPK cascade. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 2684–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Angelopoulos, N.; Xu, Y.; Grothey, A.; Nunes, J.; Stebbing, J.; Giamas, G. Proteomic profile of KSR1-regulated signalling in response to genotoxic agents in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 151, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Park, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Jun, M.; Lee, J.; Baek, J.; Park, H.; Bang, J.; Ro, S.W. Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) Promotes Liver Carcinogenesis via Activation of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK Signaling Pathway. JHEP Rep 2025, 7, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drizyte-Miller, K.; Talabi, T.; Somasundaram, A.; Cox, A.D.; Der, C.J. KRAS: The Achilles’ heel of pancreas cancer biology. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e191939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liao, X.; Tsai, H.I. KRAS mutation: The booster of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma transformation and progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1147676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbrook, C.J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Pasca di Magliano, M.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer: Advances and challenges. Cell 2023, 186, 1729–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G.C.; Candido, S.; Carbone, M.; Raiti, F.; Colaianni, V.; Garozzo, S.; Cinà, D.; McCubrey, J.A.; Libra, M. BRAF mutations in papillary thyroid carcinoma and emerging targeted therapies (review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2012, 6, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.P.; Feng, T.; Sigoillot, F.D.; Geyer, F.C.; Shirley, M.D.; Ruddy, D.A.; Rakiec, D.P.; Freeman, A.K.; Engelman, J.A.; Jaskelioff, M.; et al. Hyperactivation of MAPK Signaling Is Deleterious to RAS/RAF-mutant Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.H.; Friskes, A.; Wang, S.; Fernandes Neto, J.M.; van Gemert, F.; Mourragui, S.; Papagianni, C.; Kuiken, H.J.; Mainardi, S.; Alvarez-Villanueva, D.; et al. Paradoxical Activation of Oncogenic Signaling as a Cancer Treatment Strategy. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1276–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet, D.; Eritja, N.; Domingo, M.; Bergada, L.; Mirantes, C.; Santacana, M.; Pallares, J.; Macià, A.; Yeramian, A.; Encinas, M.; et al. KSR1 is overexpressed in endometrial carcinoma and regulates proliferation and TRAIL-induced apoptosis by modulating FLIP levels. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 1529–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, N.S.; Scopton, A.P.; Dar, A.C. Small molecule stabilization of the KSR inactive state antagonizes oncogenic Ras signalling. Nature 2016, 537, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Huang, Z.; Pei, H.; Jia, Z.; Zheng, J. Molecular glue-mediated targeted protein degradation: A novel strategy in small-molecule drug development. iScience 2024, 27, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, S.B.; Crews, C.M. Major advances in targeted protein degradation: PROTACs, LYTACs, and MADTACs. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, K.; Tong, A.; Jia, D. Targeted protein degradation: Mechanisms, strategies and application. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.H.; Sun, H.; Nichols, J.G.; Crooke, S.T. RNase H1-Dependent Antisense Oligonucleotides Are Robustly Active in Directing RNA Cleavage in Both the Cytoplasm and the Nucleus. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, R.; Krainer, A.R.; Altman, S. RNA therapeutics: Beyond RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbia, D.; De Martin, S. Insights into Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Pathophysiology to Novel Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, E.; Sarkar, D. Emerging Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers 2022, 14, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevola, R.; Tortorella, G.; Rosato, V.; Rinaldi, L.; Imbriani, S.; Perillo, P.; Mastrocinque, D.; La Montagna, M.; Russo, A.; Di Lorenzo, G.; et al. Gender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Risk Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology 2023, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyn, P.; Ahmed, A.; Kim, D. Current epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampimukhi, M.; Qassim, T.; Venu, R.; Pakhala, N.; Mylavarapu, S.; Perera, T.; Sathar, B.S.; Nair, A. A Review of Incidence and Related Risk Factors in the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cureus 2023, 15, e49429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, M.; Lopez, A.; Lin, E.; Sales, D.; Perets, R.; Jain, P. Progress on Ras/MAPK Signaling Research and Targeting in Blood and Solid Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Ro, S.W. MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athuluri-Divakar, S.K.; Vasquez-Del Carpio, R.; Dutta, K.; Baker, S.J.; Cosenza, S.C.; Basu, I.; Gupta, Y.K.; Reddy, M.V.; Ueno, L.; Hart, J.R.; et al. A Small Molecule RAS-Mimetic Disrupts RAS Association with Effector Proteins to Block Signaling. Cell 2016, 165, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, P.; Freese, K.; Mahli, A.; Thasler, W.E.; Hellerbrand, C.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Combined effects of PLK1 and RAS in hepatocellular carcinoma reveal rigosertib as promising novel therapeutic “dual-hit” option. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 3605–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghousein, A.; Mosca, N.; Cartier, F.; Charpentier, J.; Dupuy, J.W.; Raymond, A.A.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Grosset, C.F. miR-4510 blocks hepatocellular carcinoma development through RAF1 targeting and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signalling inactivation. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D.; Bao, L.; Yin, T.; Chen, H. MEK inhibition by cobimetinib suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessard, A.; Frémin, C.; Ezan, F.; Fautrel, A.; Gailhouste, L.; Baffet, G. RNAi-mediated ERK2 knockdown inhibits growth of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5315–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozakis-Adcock, M.; Fernley, R.; Wade, J.; Pawson, T.; Bowtell, D. The SH2 and SH3 domains of mammalian Grb2 couple the EGF receptor to the Ras activator mSos1. Nature 1993, 363, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tu, D.; Peng, R.; Tang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Su, B.; Wang, S.; Tang, H.; Jin, S.; Jiang, G.; et al. RNF173 suppresses RAF/MEK/ERK signaling to regulate invasion and metastasis via GRB2 ubiquitination in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadari, Y.R.; Kouhara, H.; Lax, I.; Schlessinger, J. Binding of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase to FRS2 is essential for fibroblast growth factor-induced PC12 cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 3966–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnick, J.M.; Meng, S.; Ren, Y.; Desponts, C.; Wang, H.G.; Djeu, J.Y.; Wu, J. Regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway by SHP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9498–9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, R.; Zhao, X.; Qu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, H.; Jin, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Shp2 SUMOylation promotes ERK activation and hepatocellular carcinoma development. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 9355–9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; Hisamoto, T.; Akiba, J.; Koga, H.; Nakamura, K.; Tokunaga, Y.; Hanada, S.; Kumemura, H.; Maeyama, M.; Harada, M.; et al. Spreds, inhibitors of the Ras/ERK signal transduction, are dysregulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma and linked to the malignant phenotype of tumors. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6056–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Wei, Y.; Huo, L.; Chen, Y.; Shang, C. miR-126-3p contributes to sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma via downregulating SPRED1. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.N.; Liu, X.Y.; Yang, Y.F.; Xiao, F.J.; Li, Q.F.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Q.W.; Wang, L.S.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, H. Regulation of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by Spred2 and correlative studies on its mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 410, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Gao, T.; Fujisawa, M.; Ohara, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Matsukawa, A. SPRED2 Is a Novel Regulator of Autophagy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells and Normal Hepatocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, K.; Seitz, T.; Li, S.; Janosch, P.; McFerran, B.; Kaiser, C.; Fee, F.; Katsanakis, K.D.; Rose, D.W.; Mischak, H.; et al. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature 1999, 401, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Tian, B.; Sedivy, J.M.; Wands, J.R.; Kim, M. Loss of Raf kinase inhibitor protein promotes cell proliferation and migration of human hepatoma cells. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma drug resistance models. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, S.; Xia, L.; Sun, Z.; Chan, K.M.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Chen, J.; Xia, Q.; Jin, H. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Signaling pathways and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.R.; He, X.L.; Li, J.; Mo, C.F. Drug Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Theoretical Basis and Therapeutic Aspects. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2024, 29, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Sun, J.; Guo, Q. Combating drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: No awareness today, no action tomorrow. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, A.D.; Duarte, S.; Sahin, I.; Zarrinpar, A. Mechanisms of drug resistance in HCC. Hepatology 2024, 79, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chan, S.W.; Liu, F.; Liu, J.; Chow, P.K.H.; Toh, H.C.; Hong, W. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Drug Therapeutic Status, Advances and Challenges. Cancers 2024, 16, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhan, M.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y. Drug resistance mechanism of kinase inhibitors in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1097277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Shi, Y.; Lv, Y.; Yuan, S.; Ramirez, C.F.A.; Lieftink, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Dias, M.H.; et al. EGFR activation limits the response of liver cancer to lenvatinib. Nature 2021, 595, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Shen, H.; Huang, W.; He, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Y. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in hepatocellular carcinoma with lenvatinib resistance. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Huang, S.; Hu, C.A.; Teng, Y. FGF19/FGFR4 signaling contributes to the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Su, W.; Song, N. Advances of Fibroblast Growth Factor/Receptor Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and its Pharmacotherapeutic Targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 650388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; Zheng, B.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, L. New knowledge of the mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, G.G.; Lai, P.B.S. Targeting hepatocyte growth factor/c-mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor axis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Rationale and therapeutic strategies. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blivet-Van Eggelpoël, M.J.; Chettouh, H.; Fartoux, L.; Aoudjehane, L.; Barbu, V.; Rey, C.; Priam, S.; Housset, C.; Rosmorduc, O.; Desbois-Mouthon, C. Epidermal growth factor receptor and HER-3 restrict cell response to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.W.; Ambe, C.M.; Hari, D.M.; Wiegand, G.W.; Miller, T.C.; Chen, J.Q.; Anderson, A.J.; Ray, S.; Mullinax, J.E.; Koizumi, T.; et al. Label-retaining liver cancer cells are relatively resistant to sorafenib. Gut 2013, 62, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezayatmand, H.; Razmkhah, M.; Razeghian-Jahromi, I. Drug resistance in cancer therapy: The Pandora’s Box of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.F.; Chen, H.L.; Tai, W.T.; Feng, W.C.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, P.J.; Cheng, A.L. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway mediates acquired resistance to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 337, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.P.; Xiong, B.H.; Zhang, Y.X.; Wang, S.L.; Zuo, Q.; Li, J. FXYD5 promotes sorafenib resistance through the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 931, 175186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, P.; Kudo, M.; Krotneva, S.; Ozgurdal, K.; Su, Y.; Proskorovsky, I. Regorafenib versus Cabozantinib as a Second-Line Treatment for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Anchored Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison of Efficacy and Safety. Liver Cancer 2023, 12, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Zhao, K.; Ye, M.; Xing, G.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Ran, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, W.; Hu, S. Efficacy and safety of second-line therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Bai, Y. Effectiveness of regorafenib in second-line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2025, 104, e41356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Bai, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cheng, C.; Ladekarl, M.; Cheng, K.C.; Chan, K.S.; Yarmohammadi, H.; Mauriz, J.L.; Zhang, Y. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib as a first-line agent alone or in combination with an immune checkpoint inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 15, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Leng, Z. Regorafenib plus programmed death-1 inhibitors vs. regorafenib monotherapy in second-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 28, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabicici, M.; Azbazdar, Y.; Ozhan, G.; Senturk, S.; Firtina Karagonlar, Z.; Erdal, E. Changes in Wnt and TGF-β Signaling Mediate the Development of Regorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line HuH7. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 639779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D.; Yan, D.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, C. Targeting SphK2 Reverses Acquired Resistance of Regorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R.; Leli, N.M.; Onorati, A.; Piao, S.; Verginadis, I.I.; Tameire, F.; Rebecca, V.W.; Chude, C.I.; Murugan, S.; Fennelly, C.; et al. ER Translocation of the MAPK Pathway Drives Therapy Resistance in BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, S.W.; Lu, J.C.; Chai, X.Q.; Li, Y.C.; Zhang, P.F.; Huang, X.Y.; Cai, J.B.; Zheng, Y.M.; Guo, X.J.; et al. KSR2-14-3-3ζ complex serves as a biomarker and potential therapeutic target in sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, M.; Buday, L.; Hegedűs, B. K-Ras prenylation as a potential anticancer target. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalnecker, C.A.; Der, C.J. RAS, wanted dead or alive: Advances in targeting RAS mutant cancers. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaay6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay, J.Y.; Cropet, C.; Mansard, S.; Loriot, Y.; De La Fouchardière, C.; Haroche, J.; Topart, D.; Tougeron, D.; You, B.; Italiano, A.; et al. Long term activity of vemurafenib in cancers with BRAF mutations: The ACSE basket study for advanced cancers other than BRAF(V600)-mutated melanoma. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Cohen, M.S. The discovery of vemurafenib for the treatment of BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauschild, A.; Grob, J.J.; Demidov, L.V.; Jouary, T.; Gutzmer, R.; Millward, M.; Rutkowski, P.; Blank, C.U.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Kaempgen, E.; et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, J.; Brady, W.E.; Vathipadiekal, V.; Lankes, H.A.; Coleman, R.; Morgan, M.A.; Mannel, R.; Yamada, S.D.; Mutch, D.; Rodgers, W.H.; et al. Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.M.; Wolters, P.L.; Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Bornhorst, M.; Shah, A.C.; et al. Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershenson, D.M.; Miller, A.; Brady, W.E.; Paul, J.; Carty, K.; Rodgers, W.; Millan, D.; Coleman, R.L.; Moore, K.N.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Trametinib versus standard of care in patients with recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer (GOG 281/LOGS): An international, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, E.L.; Durham, B.H.; Ulaner, G.A.; Drill, E.; Buthorn, J.; Ki, M.; Bitner, L.; Cho, H.; Young, R.J.; Francis, J.H.; et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature 2019, 567, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Cohen, J.V.; Tarantino, G.; Lian, C.G.; Liu, D.; Haq, R.; Hodi, F.S.; Lawrence, D.P.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Knoerzer, D.; et al. A Phase II Study of ERK Inhibition by Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozohanics, O.; Ambrus, A. Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry: A Novel Structural Biology Approach to Structure, Dynamics and Interactions of Proteins and Their Complexes. Life 2020, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, B.R.; Vieira, H.M.; Rao, C.; Hughes, J.M.; Beckley, Z.M.; Huisman, D.H.; Chatterjee, D.; Sealover, N.E.; Cox, K.; Askew, J.W.; et al. SOS1 and KSR1 modulate MEK inhibitor responsiveness to target resistant cell populations based on PI3K and KRAS mutation status. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2313137120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atefi, M.; Avramis, E.; Lassen, A.; Wong, D.J.; Robert, L.; Foulad, D.; Cerniglia, M.; Titz, B.; Chodon, T.; Graeber, T.G.; et al. Effects of MAPK and PI3K pathways on PD-L1 expression in melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3446–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedognetti, D.; Roelands, J.; Decock, J.; Wang, E.; Hendrickx, W. The MAPK hypothesis: Immune-regulatory effects of MAPK-pathway genetic dysregulations and implications for breast cancer immunotherapy. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2017, 1, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Protein | Binding Partner | Functional Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchoring | CNK1 (CNKSR1) | RAF-1, Src, KSR | Upon RAS activation, promotes RAF relocalization/oligomerization → enhances RAF/MEK/ERK activation | [4,21] |

| FLOT1/2 (Flotillins) | CRAF, MEK1/2, ERK1/2 | Support EGFR clustering/activation; upon stimulation enhance CRAF/MEK/ERK signaling | [4,21] | |

| LAT, NTAL | Grb2, Gads, PLCγ1, Sos1 | Nucleate membrane-proximal signalosomes | [4,21] | |

| PAQR10/11 | H-, N-, KRAS4A, RasGRP1 | Anchor RAS to the Golgi → spatial control of signaling | [27] | |

| SEF (IL17RD) | p-MEK, p-ERK | Binds p-MEK at Golgi; potentiates RAF/MEK/ERK signaling | [21] | |

| Docking | DOK1/2 | Activated RTKs (EGFR, RET) via PTB | Docking adaptors that assemble signaling complexes | [21] |

| IRS2 | Insulin receptor (RTKs) | Couples RTKs to downstream effectors | [21] | |

| β-arrestin1/2 | GPCRs; RAF/MEK/ERK | Scaffolds RAF/MEK/ERK at plasma membrane and endosomes | [21] | |

| FRS2 | RTKs, SHP2, GRB2 | Central docking adaptor linking RTKs to Ras/ERK | [63] | |

| Adapter | CRK/CRKL | Multiple pTyr ligands | Promotes ERK signaling by coupling pTyr scaffolds to C3G → Rap1 → B-Raf → MEK → ERK | [36] |

| Grb2 | pTyr proteins (SH2); SOS1 (N-SH3); Gab1 (C-SH3) | Core adaptor coupling RTKs to RAS via SOS | [37] | |

| Shc (ShcA/SHC1) | RTKs/integrins → Grb2 | RTK-induced phosphorylation enables Grb2 binding to activate RAS | [40] | |

| SHP2 (PTPN11) | Gab1 (EGFR and other RTKs), FRS2 (FGFRs) | Tyr phosphorylation (e.g., Y542) relieves autoinhibition → supports RAS pathway | [41] | |

| Paxillin | ERK/MAPK module components | Recruits/organizes ERK module at adhesions | [42] | |

| Scaffold | KSR1 and 2 | RAF (BRAF, CRAF), MEK1/2, ERK1/2 | Scaffold RAF–MEK–ERK at the membrane to boost efficient and precise RAS signaling | [64,65] |

| IQGAP1 | EGFR (direct/via ShcA), HER2 heterodimers | Bridges EGFR/HER2 to MAPK; tunes receptor trafficking and signal amplitude | [46] | |

| SHOC2 | MRAS, PP1, RAF-1 | Dephosphorylates inhibitory RAF-1 Ser259 site → enables RAF activation | [46,66,67,68] | |

| Negative Modulator | SPRED family (SPRED1 and 2) | NF1 | Negative regulation of RTK→RAS–MAPK by modulating RasGAPs | [49] |

| Sprouty family (SPRY 1–4) | GRB2 (SH2) | Sequesters GRB2 away from SOS → suppresses RAS activation | [51] | |

| RKIP (PEBP1) | Raf-1, MEK | Blocks Raf-1/MEK interaction or binds Raf-1 N-region to inhibit MEK phosphorylation | [52] | |

| Erbin | ERBB2, Shoc2 | Modulates Shoc2–ERK signal strength | [47] | |

| DUSP | ERK1/2 | Acts as negative feedback regulators → directly dephosphorylates MAPKs (especially ERK) | [59,60] |

| Agent | Target | Model | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rigosertib | RAS | in vitro (I) | Reduced HCC cell proliferation | [112] |

| miR-4510 | RAF | in vitro (I) | Suppressed HCC cell proliferation | [113] |

| in vivo (I) | Decreased tumor size and proliferation | |||

| cobimetinib | MEK | in vitro (I) | Reduced HCC cell proliferation | [114] |

| in vivo (I) | Decreased tumor development | |||

| siRNA | ERK | in vitro (I) | Decreased HCC cell proliferation | [115] |

| RNF173 | GRB2 | in vitro (I) | Inhibited RAS/MAPK signaling | [117] |

| shRNA SUMO1 | SHP2 | in vitro (I) in vivo (A) | Inhibited RAS/MAPK signaling Increased tumor growth | [120] |

| miR-126 miR-126 inhibitor | SPRED1 | in vitro (I) in vivo (A) | Increased proliferation and ERK phosphorylation Reduced tumor growth | [122] |

| SPRED2 siRNA | SPRED2 | in vitro (A) in vivo (I) | Reduced proliferation and ERK phosphorylation Increased tumor growth | [123] |

| siRNA RKIP | RKIP | in vitro (I) in vitro (A) | Increased MEK phosphorylation Reduced HCC cell proliferation and migration | [126] |

| Drug | Target | Resistance Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib | VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR | EGFR–PAK2–ERK5 signaling activation | [134] |

| Loss of NF1 and DUSP9 | [135] | ||

| Sorafenib | VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR, RAF | Overexpression of FGF | [136] |

| Activation of HGF/c-Met axis | [139] | ||

| Activation of EGFR and HER3 | [140] | ||

| Enrichment of cancer stem cells | [141] | ||

| Compensatory activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway | [143] | ||

| Regorafenib | VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR | Activation of TGF-β signaling | [150] |

| NF-κB and STAT3 activation (SphK2 overexpression) | [151] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, H.; Park, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Ro, S.W. Targeting Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101348

Moon H, Park H, Lee S, Lee S, Ro SW. Targeting Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(10):1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101348

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Hyuk, Hyunjung Park, Soyun Lee, Sangjik Lee, and Simon Weonsang Ro. 2025. "Targeting Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) for Cancer Therapy" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 10: 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101348

APA StyleMoon, H., Park, H., Lee, S., Lee, S., & Ro, S. W. (2025). Targeting Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics, 17(10), 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101348