Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and S.Z.-N.; Data curation, S.M., H.S. and N.M.; Funding acquisition, S.Z.-N.; Investigation, N.S., V.R., N.M. and S.M.; Resources, S.Z.-N.; Supervision, S.Z.-N.; Validation, H.S.; Visualization, N.S., V.R., S.M. and S.Z.-N.; Writing—original draft, N.S., V.R. and S.Z.-N.; Writing—review and editing, E.F. and S.Z.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Concentrations in plasma (dark blue line) and lung tissue (bright blue line) of (

a) RIF, (

b) ETH, and (

c) MOX, taken from [

22], [

23], and [

24], respectively.

Figure 1.

Concentrations in plasma (dark blue line) and lung tissue (bright blue line) of (

a) RIF, (

b) ETH, and (

c) MOX, taken from [

22], [

23], and [

24], respectively.

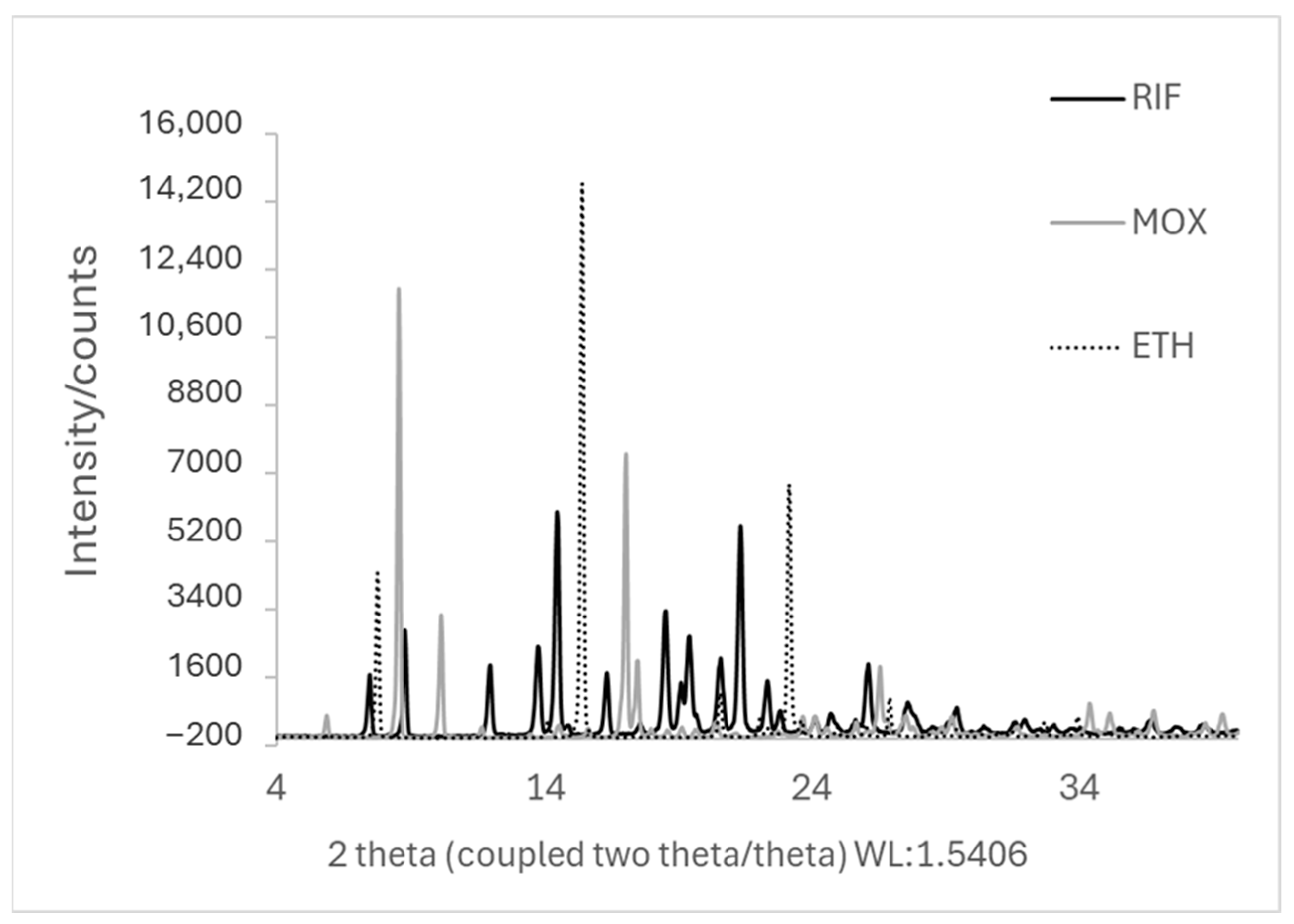

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of the starting materials (jet-milled RIF, ETH, and MOX).

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of the starting materials (jet-milled RIF, ETH, and MOX).

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the different RIF-ETH formulations: (A) spray-dried (SD) and ball-milled (BM) in a molar ratio of 1:1; (B) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:6; (C) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:45.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the different RIF-ETH formulations: (A) spray-dried (SD) and ball-milled (BM) in a molar ratio of 1:1; (B) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:6; (C) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:45.

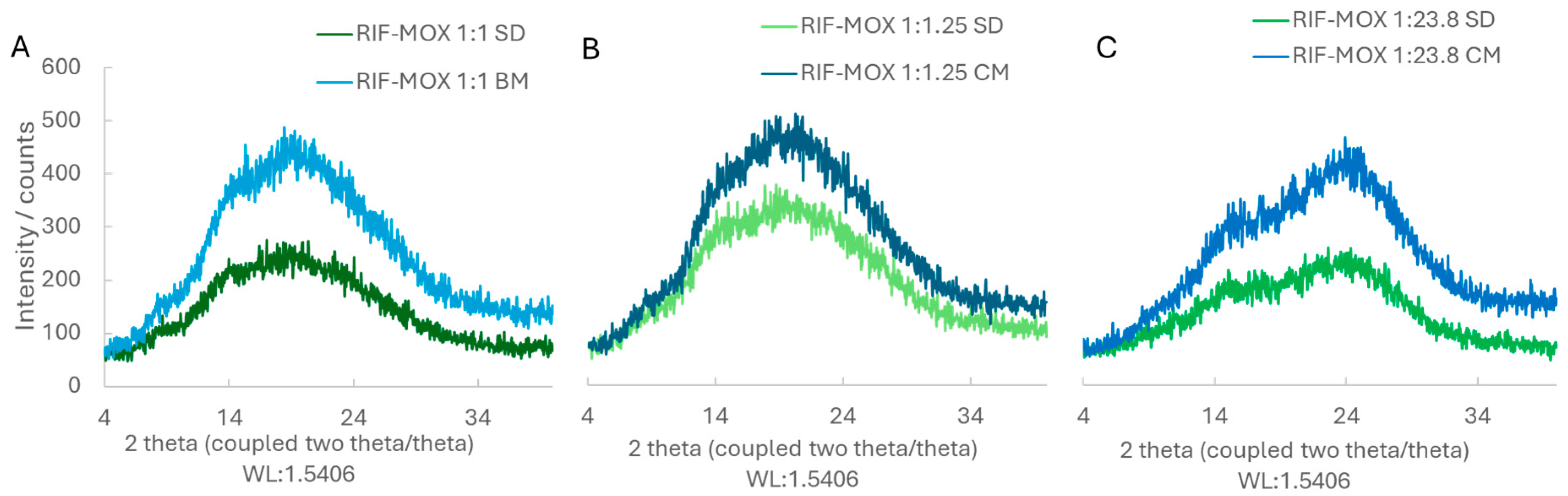

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the different RIF-MOX formulations: (A) spray-dried (SD) and ball-milled (BM) in a molar ratio of 1:1; (B) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:1.25; (C) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:23.8.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the different RIF-MOX formulations: (A) spray-dried (SD) and ball-milled (BM) in a molar ratio of 1:1; (B) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:1.25; (C) SD and BM in a molar ratio of 1:23.8.

Figure 5.

SEM images of RIF-ETH formulations in different molar ratios and prepared via milling (BM) or spray drying (SD): (A1) RIF-ETH 1:1 BM, (B1) RIF-ETH 1:1 SD, (A2) RIF-ETH 1:6 BM, (B2) RIF-ETH 1:6 SD, (A3) RIF-ETH 1:45 BM, and (B3) RIF-ETH 1:45 SD (image width 22.87 µm).

Figure 5.

SEM images of RIF-ETH formulations in different molar ratios and prepared via milling (BM) or spray drying (SD): (A1) RIF-ETH 1:1 BM, (B1) RIF-ETH 1:1 SD, (A2) RIF-ETH 1:6 BM, (B2) RIF-ETH 1:6 SD, (A3) RIF-ETH 1:45 BM, and (B3) RIF-ETH 1:45 SD (image width 22.87 µm).

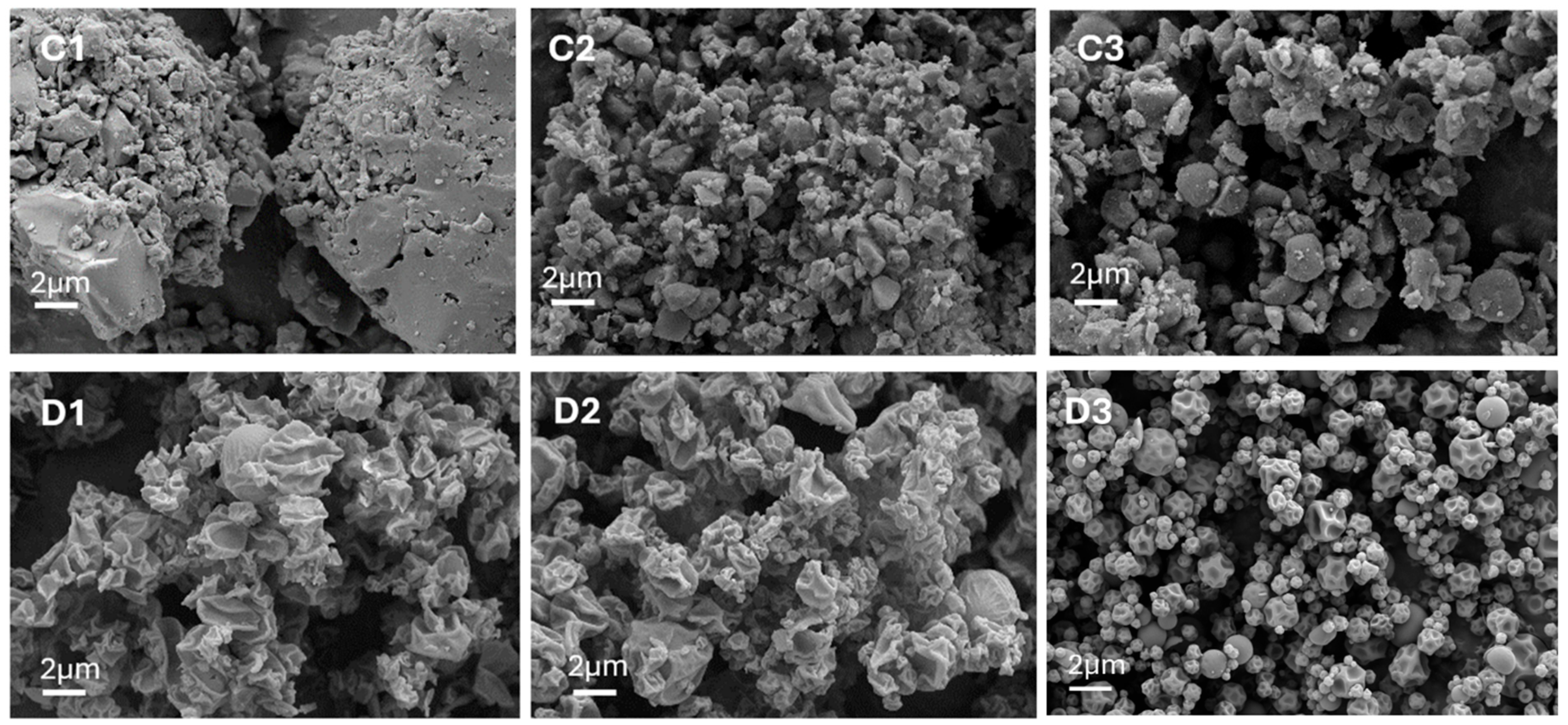

Figure 6.

SEM images of RIF-MOX formulations in different molar ratios and prepared via ball milling (BM), co-milling (CM), or spray drying (SD): (C1) RIF-MOX 1:1 BM, (D1) RIF-MOX 1:1 SD, (C2) RIF-MOX 1:1.25 CM, (D2) RIF-MOX 1:1.25 SD, (C3) RIF-MOX 1:23.8 CM, and (D3) RIF-MOX 1:23.8 SD (image width 22.87 µm).

Figure 6.

SEM images of RIF-MOX formulations in different molar ratios and prepared via ball milling (BM), co-milling (CM), or spray drying (SD): (C1) RIF-MOX 1:1 BM, (D1) RIF-MOX 1:1 SD, (C2) RIF-MOX 1:1.25 CM, (D2) RIF-MOX 1:1.25 SD, (C3) RIF-MOX 1:23.8 CM, and (D3) RIF-MOX 1:23.8 SD (image width 22.87 µm).

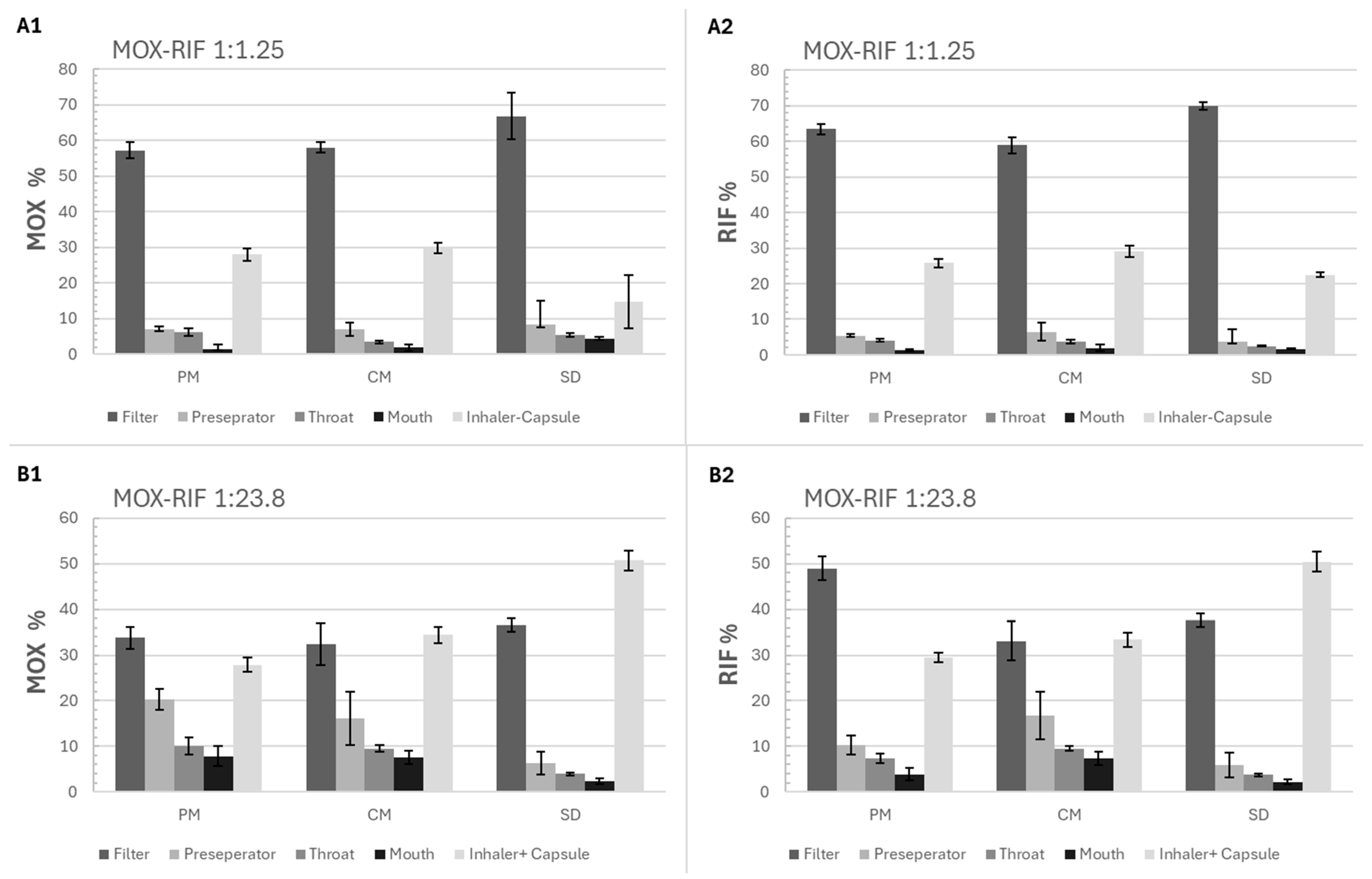

Figure 7.

Percentage of RIF and MOX depositions in each stage of FSI (filter, preparator, throat, mouth, and inhaler + capsule) for the physical mixture (PM), spray-drying (SD), and co-milling (CM) formulations of 2 molar ratios (1:1.25 and 1:23.8), (A1) MOX percentage for the 1:1.25 formulations, (A2) RIF percentage for the 1:1.25 formulations, (B1) MOX percentage for the 1:23.8 formulations, (B2) RIF percentage for the 1:23.8 formulations, mean ± SD, n = 3.

Figure 7.

Percentage of RIF and MOX depositions in each stage of FSI (filter, preparator, throat, mouth, and inhaler + capsule) for the physical mixture (PM), spray-drying (SD), and co-milling (CM) formulations of 2 molar ratios (1:1.25 and 1:23.8), (A1) MOX percentage for the 1:1.25 formulations, (A2) RIF percentage for the 1:1.25 formulations, (B1) MOX percentage for the 1:23.8 formulations, (B2) RIF percentage for the 1:23.8 formulations, mean ± SD, n = 3.

Figure 8.

Emitted fraction (EF) and fine particle fraction (FPF) of MOX and RIF for the physical mixture (PM), spray-drying (SD), and co-milling (CM) formulations of 2 molar ratios (1:1.25 and 1:23.8), (A1) EF and FPF of MOX for the 1:1.25 formulations, (A2) EF and FPF of RIF for the 1:1.25 formulations, (B1) EF and FPF of MOX for the 1:23.8 formulations, (B2) EF and FPF of RIF for the 1:23.8 formulations, mean ± SD, n = 3, significant at * p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 8.

Emitted fraction (EF) and fine particle fraction (FPF) of MOX and RIF for the physical mixture (PM), spray-drying (SD), and co-milling (CM) formulations of 2 molar ratios (1:1.25 and 1:23.8), (A1) EF and FPF of MOX for the 1:1.25 formulations, (A2) EF and FPF of RIF for the 1:1.25 formulations, (B1) EF and FPF of MOX for the 1:23.8 formulations, (B2) EF and FPF of RIF for the 1:23.8 formulations, mean ± SD, n = 3, significant at * p ≤ 0.05.

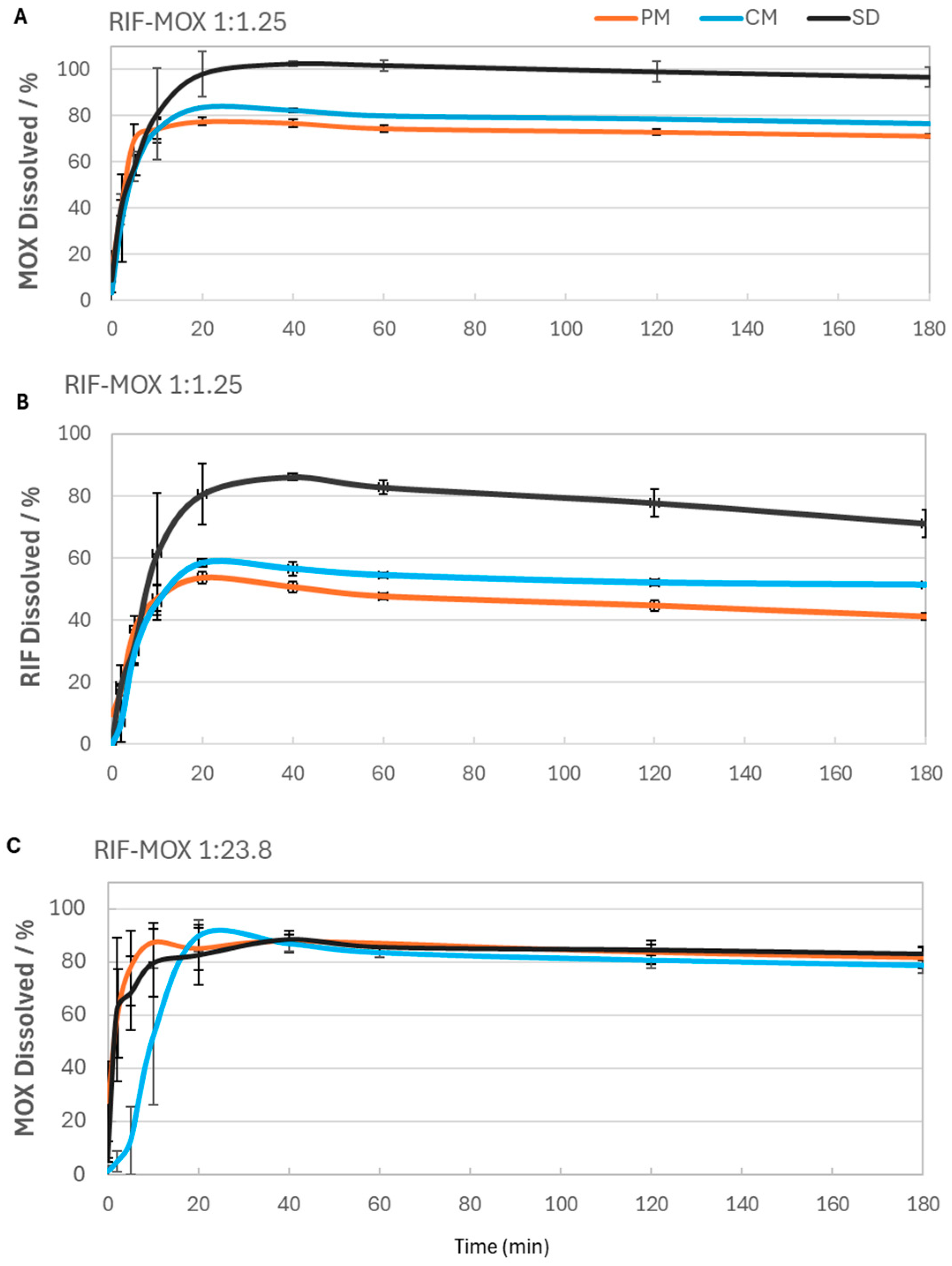

Figure 9.

RIF-MOX formulation dissolution profiles over time for both RIF and MOX: (A) MOX dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:1.25, (B) RIF dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:1.25, and (C) MOX dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:23.8; mean ± SD, n = 3.

Figure 9.

RIF-MOX formulation dissolution profiles over time for both RIF and MOX: (A) MOX dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:1.25, (B) RIF dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:1.25, and (C) MOX dissolved for RIF-MOX 1:23.8; mean ± SD, n = 3.

Table 1.

Tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients (Kp values) of the different compartments used in the simulation.

Table 1.

Tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients (Kp values) of the different compartments used in the simulation.

| Compartment | Kp Value—RIF | Kp Value—ETH | Kp Value—MOX |

|---|

| Lung | 0.14 | 7.92 | 4.9 |

| Adipose | 0.28 | 1.22 | 0.52 |

| Muscle | 0.15 | 9.14 | 2 |

| Liver | 0.29 | 8.65 | 5.69 |

| Spleen | 0.19 | 8.75 | 4.01 |

| Heart | 0.14 | 7.48 | 2.88 |

| Brain | 0.16 | 8.9 | 0.64 |

| Kidney | 0.24 | 8.07 | 6.26 |

| Skin | 0.19 | 6.26 | 1.74 |

| ReproOrg | 0.24 | 8.07 | 6.33 |

| RedMarrow | 0.3 | 3.15 | 0.75 |

| YellowMarrow | 0.3 | 3.15 | 0.75 |

| RestOfBody | 5 | 46 | 17.55 |

Table 2.

Input parameter GP. bp ratio: blood-to-plasma ratio, fu: fraction unbound, Vd

ss: volume of distribution at steady state, P

eff: effective permeability, CL

iv: intravenous clearance (systemic clearance), CL

R: renal clearance [

22].

Table 2.

Input parameter GP. bp ratio: blood-to-plasma ratio, fu: fraction unbound, Vd

ss: volume of distribution at steady state, P

eff: effective permeability, CL

iv: intravenous clearance (systemic clearance), CL

R: renal clearance [

22].

| Parameter (Unit) | Value—RIF | Value—ETH | Value—MOX | Reference |

|---|

| Dose (mg) | 300 | 1974.6 | 200 | [22,23,24] |

| MW (g/mol) | 822.94 | 204.31 | 401.44 | GP |

| bp ratio | 0.67 | 0.94 | 1.14 | Refs. [22,25], GP |

| fu | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.52 | Ref. [22], GP, ref. [24] |

| Vdss (L/kg) | 0.42 | 6.1 | 1.9 | Refs. [22,23,26] |

| Peff (×10−4 cm/s) | 1.3 | 0.67 | 1.45 | Optimized GP |

| CLiv (L/h) | 8.307 | 41.9 | 13.15 | Refs. [22,26,27] |

| CLR (L/h) | 1.5 | 32.4 | 2.54 | Refs. [22,26,27] |

Table 3.

Mean anthropometric parameters of the study population.

Table 3.

Mean anthropometric parameters of the study population.

| Parameter (Unit) | Value—RIF | Value—ETH | Value—MOX |

|---|

| Age (years) | 30 | 39.1 | 33.6 |

| Body weight (kg) | 85.5 | 79.3 | 81.5 |

| Body height (cm) | 176.4 | 172.6 (estimated) | 182.2 |

| Percentage male | 100 | 57 | 100 |

| Race/Sex | 1 Caucasian | 6 white female, 3 black males, 5 while males | 45 Caucasian |

Table 4.

The different API-API combinations, molar ratios, and formulations for analysis.

Table 4.

The different API-API combinations, molar ratios, and formulations for analysis.

| API-API Combination | Formulation | Molar Ratio | Comment |

|---|

| RIF-ETH | BM, CM, SD * | 1:1 | ML-predicted |

| RIF-ETH | BM, SD | 1:6 | The literature |

| RIF-ETH | BM, SD | 1:45 | PBPK modeling |

| RIF-MOX | BM, SD | 1:1 | ML-predicted |

| RIF-MOX | PM, CM, SD | 1:1.25 | The literature |

| RIF-MOX | PM, CM, SD | 1:23.81 | PBPK modeling |

Table 5.

Chromatographic conditions for HPLC analysis of RIF and MOX.

Table 5.

Chromatographic conditions for HPLC analysis of RIF and MOX.

| Parameter | Condition |

|---|

| Column | Waters Acquity UPLC HSS Cyano (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm particle size), 25 °C |

| Mobile phase | A: 10 mM ammonium formate buffer (0.630 g/L), pH 4.0 (adjusted with diluted formic acid solution)

B: 0.1% formic acid in methanol |

| Gradient program | 0.0–1.5 min: 95% A

2.0 min: 50% A

6.0–7.0 min: 10% A

8.0 min: Return to 95% A

Total run time ≈ 12 min |

| Flow rate | 0.35 mL/min |

| Injection volume | 1 µL |

| Sample manager temp. | 10 °C |

| Detection wavelengths | 295 nm (MOX); 335 nm (RIF) |

Table 6.

PK-parameters, maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC), of the clinical trials (Obs.) compared to the ones from the simulation (Sim.) with the percentage prediction error (%PE).

Table 6.

PK-parameters, maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC), of the clinical trials (Obs.) compared to the ones from the simulation (Sim.) with the percentage prediction error (%PE).

| | RIF | ETH | MOX |

|---|

| | Obs. | Sim. | %PE | Obs. | Sim. | %PE | Obs. | Sim. | %PE |

|---|

| Cmax (µg/mL) | 5.81 | 6.01 | 3.44 | 3.54 | 3.56 | 0.68 | 1.16 | 1.20 | 3.48 |

| AUC0-t (µg-h/mL) | 31.02 | 33.67 | 8.54 | 27.80 | 28.52 | 2.57 | 11.88 | 11.25 | 5.27 |

| AUC0-inf (µg-h/mL) | 31.02 | 34.23 | 10.35 | 30.76 | 30.06 | 2.27 | 14.57 | 13.58 | 6.75 |

Table 7.

PBPK-model-estimated lung exposure for RIF, ETH, and MOX.

Table 7.

PBPK-model-estimated lung exposure for RIF, ETH, and MOX.

| API | Estimated Lung Exposure (%) |

|---|

| RIF | 1.7 |

| ETH | 13 |

| MOX | 32.5 |

Table 8.

Inhalation doses of RIF, ETH, and MOX based on predicted estimated lung exposure and 40% FPF.

Table 8.

Inhalation doses of RIF, ETH, and MOX based on predicted estimated lung exposure and 40% FPF.

| API | Inhalation Dose [mg] (Model) | Inhalation Dose [mg] (Literature) |

|---|

| RIF | 25.65 | 150 |

| ETH | 390 | 300 |

| MOX | 325 | 100 |

Table 9.

Molar ratio of RIF-ETH and RIF-MOX inhalation doses.

Table 9.

Molar ratio of RIF-ETH and RIF-MOX inhalation doses.

| API-API | Molar Ratio (Model) | Molar Ratio (Literature) |

|---|

| RIF-ETH | 1:45 | 1:6 |

| RIF-MOX | 1:23.8 | 1:1.25 |

Table 10.

Particle size distribution of RIF–ETH formulations.

Table 10.

Particle size distribution of RIF–ETH formulations.

| Formulation | X10 µm | X50 µm | X90 µm | SPAN | SMD µm |

|---|

| RIF-ETH 1-1 SD | 1.59 ± 0.50 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 15.34 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 2.17 ± 0.09 |

| RIF-ETH 1-1 BM | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 3.85 ± 0.51 | 10.16 ± 1.71 | 64.23 ± 6.87 | 2.38 ± 0.36 |

| RIF-ETH 1:6 SD | 1.40 ± 0.05 | 6.68 ± 0.22 | 22.77 ± 1.82 | 3.20 ± 0.19 | 3.28 ± 0.11 |

| RIF-ETH 1:6 BM | 2.31 ± 0.40 | 23.06 ± 5.94 | 114.85 ± 32.8 | 4.93 ± 0.75 | 6.13 ± 0.94 |

| RIF-ETH 1:45 SD | 1.30 ± 0.04 | 3.77 ± 0.23 | 7.23 ± 0.28 | 1.57 ± 0.04 | 2.63 ± 0.09 |

| RIF-ETH 1:45 BM | 1.69 ± 0.12 | 9.84 ± 2.12 | 53.13 ± 1.10 | 5.50 ± 1.27 | 4.44 ± 0.42 |

Table 11.

Particle size distribution of RIF–MOX formulations.

Table 11.

Particle size distribution of RIF–MOX formulations.

| Formulation | X10 µm | X50 µm | X90 µm | SPAN | SMD µm |

|---|

| RIF-MOX 1:1 SD | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 2.82 ± 0.07 | 4.94 ± 0.14 | 1.39 ± 0.01 | 1.88 ± 0.04 |

| RIF-MOX 1:1 BM | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 4.31 ± 0.18 | 20.00 ± 2.44 | 4.40 ± 0.39 | 2.35 ± 0.06 |

| RIF-MOX 1:1.25 PM | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 3.96 ± 0.16 | 7.30 ± 0.26 | 1.61 ± 0.03 | 2.14 ± 0.06 |

| RIF-MOX 1:1.25 SD | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 2.99 ± 0.18 | 5.38 ± 0.32 | 1.45 ± 0.02 | 1.96 ± 0.08 |

| RIF-MOX 11.25 CM | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 3.84 ± 0.25 | 7.27 ± 0.28 | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 2.24 ± 0.10 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 PM | 1.32 ± 0.01 | 5.94 ± 0.15 | 11.14 ± 0.24 | 1.65 ± 0.02 | 2.90 ± 0.04 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 SD | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 3.18 ± 0.33 | 6.91 ± 0.70 | 1.93 ± 0.04 | 1.82 ± 0.13 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 CM | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 4.92 ± 0.87 | 12.05 ± 0.83 | 2.29 ± 0.27 | 2.43 ± 0.23 |

Table 12.

Mean drug content (%) and mixing homogeneity (deviation in mean drug content, relative standard deviation, (%)) for RIF and MOX within the 3 formulations RIF-MOX PM, RIF-MOX SD, and RIF-MOX CM (n = 10).

Table 12.

Mean drug content (%) and mixing homogeneity (deviation in mean drug content, relative standard deviation, (%)) for RIF and MOX within the 3 formulations RIF-MOX PM, RIF-MOX SD, and RIF-MOX CM (n = 10).

| | Mean Drug Content RIF/% | Mixing Homogeneity RIF/% | Mean Drug Content MOX/% | Mixing Homogeneity MOX/% |

|---|

| RIF + MOX PM 1:1.25 | 92.8 ± 10.9 | 11.8 | 86.8 ± 9.7 | 11.2 |

| RIF + MOX SD 1:1.25 | 95.7 ± 2.5 | 2.6 | 89.0 ± 3.0 | 3.3 |

| RIF + MOX CM 1:1.25 | 90.3 ± 2.5 | 2.7 | 89.2 ± 3.0 | 3.4 |

| RIF + MOX PM 1:23.8 | 91.5 ± 3.2 | 3.5 | 93.6 ± 2.4 | 2.5 |

| RIF + MOX SD 1:23.8 | 97.1 ± 4.8 | 4.9 | 103.2 ± 5.3 | 5.0 |

| RIF + MOX CM 1:23.8 | 87.4 ± 3.4 | 3.9 | 95.1 ± 3.0 | 3.1 |

Table 13.

EF, FPM, and FPF RIF-MOX for both RIF and MOX.

Table 13.

EF, FPM, and FPF RIF-MOX for both RIF and MOX.

| Formulation | MOX | RIF |

|---|

| EF % | FPM mg | FPF% | EF % | FPM mg | FPF % |

|---|

| RIF-MOX 1:1.25 PM | 71.9 ± 1.7 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 79.5 ± 1.4 | 74.2 ± 1.2 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 85.4 ± 1.1 |

| RIF-MOX 1:1.25 CM | 70.3 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 82.6 ± 3.9 | 71.0 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 83.0 ± 4.8 |

| RIF-MOX 1:1.25 SD | 85.2 ± 7.6 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 78.3 ± 1.5 | 77.5 ± 0.7 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 90.0 ± 0.6 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 PM | 72.1 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 47.0 ± 4.2 | 70.6 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.05 | 69.4 ± 4.5 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 CM | 65.6 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 49.5 ± 8.3 | 66.6 ± 1.6 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 49.8 ± 7.6 |

| RIF-MOX 1:23.8 SD | 49.2 ± 2.2 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 74.6 ± 5.3 | 49.5 ± 2.1 | 0.6 ± 0.01 | 76.2 ± 5.5 |