Accessing HIV Care to Irregular Migrants in Israel, 2019–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort and Data Collection

2.2. Diagnosis, Monitoring and ART Under the PPP

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Sequencing, DRM Analysis and Genotyping

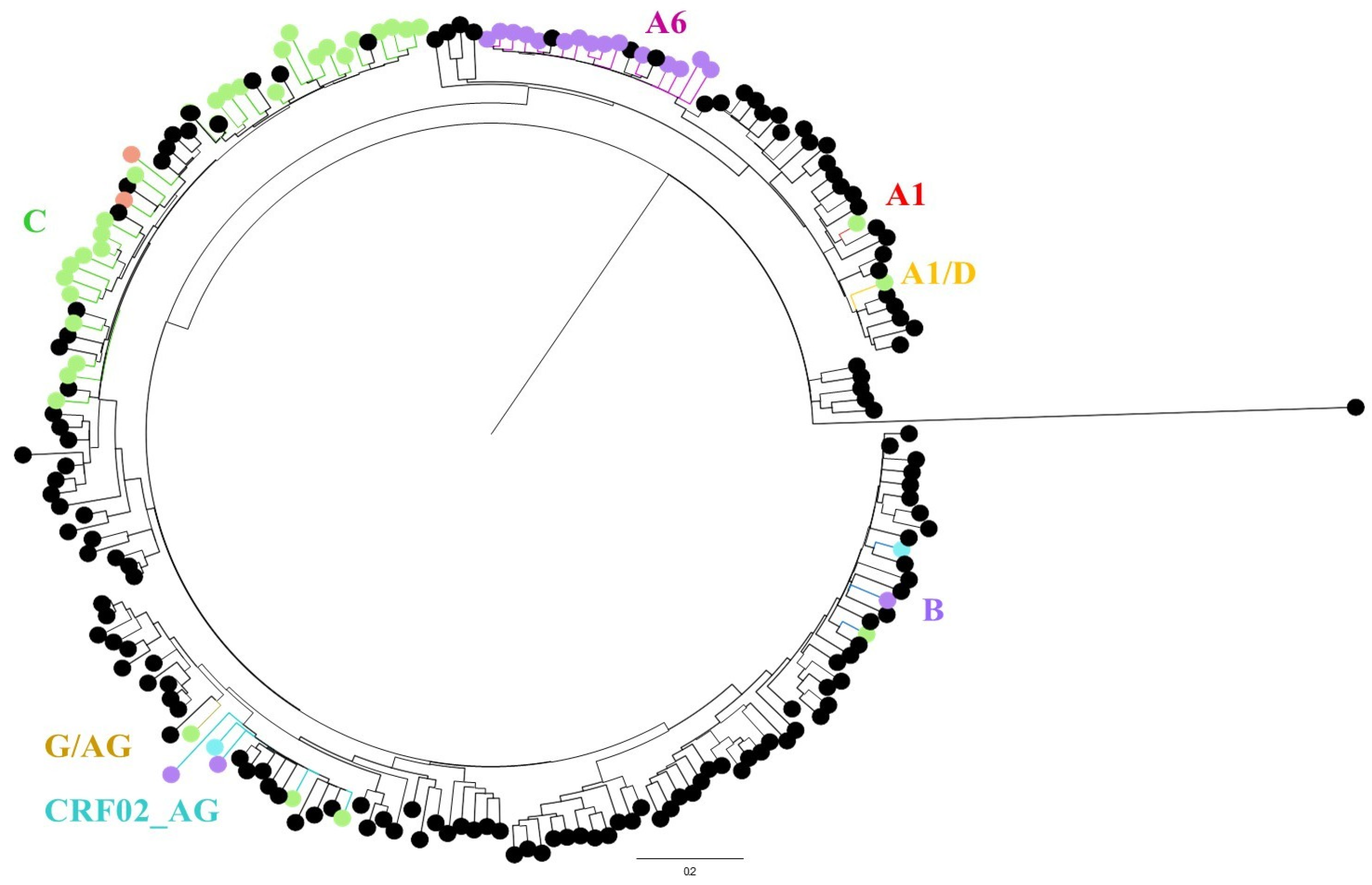

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Ethical Approval

3. Results

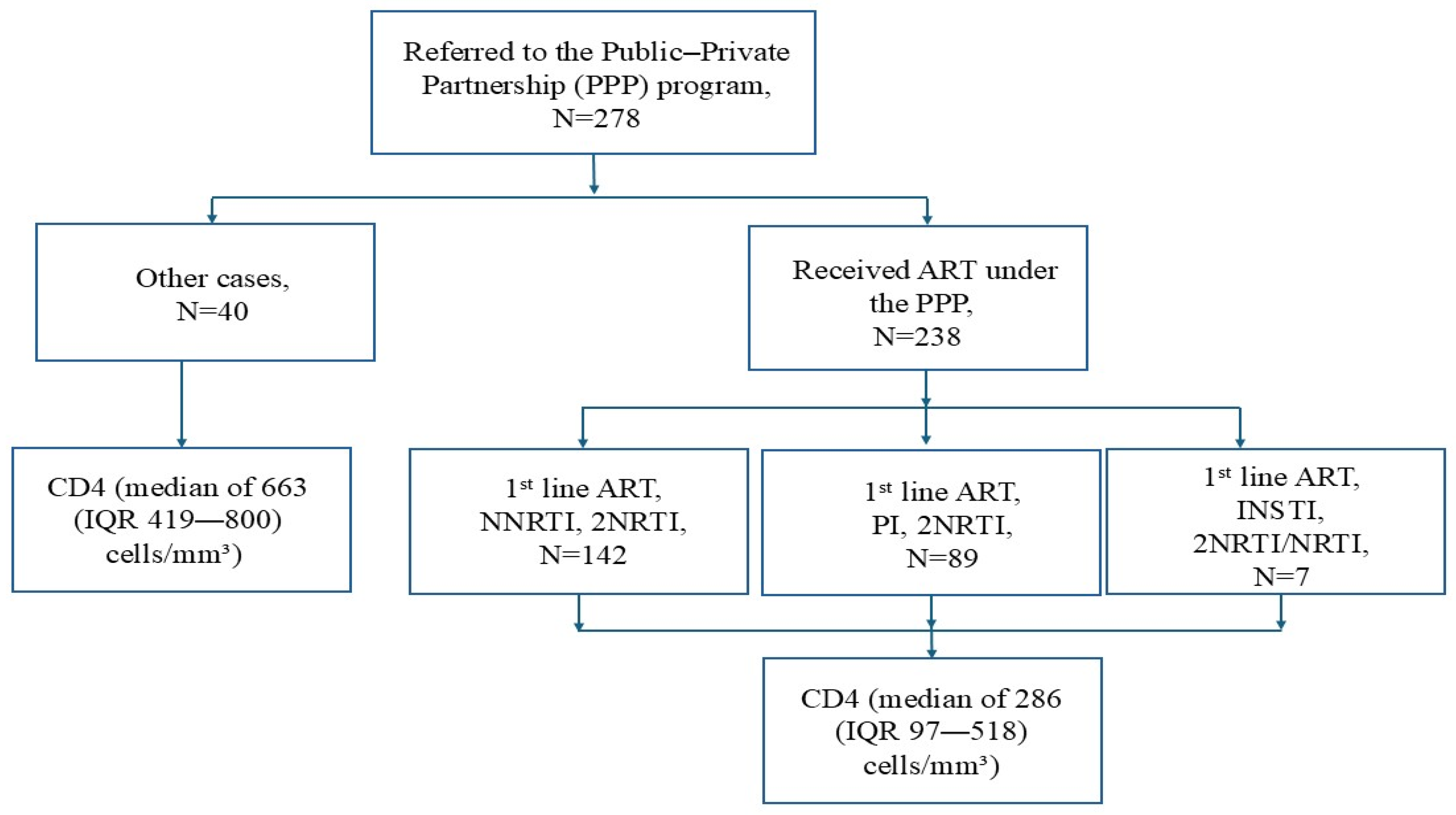

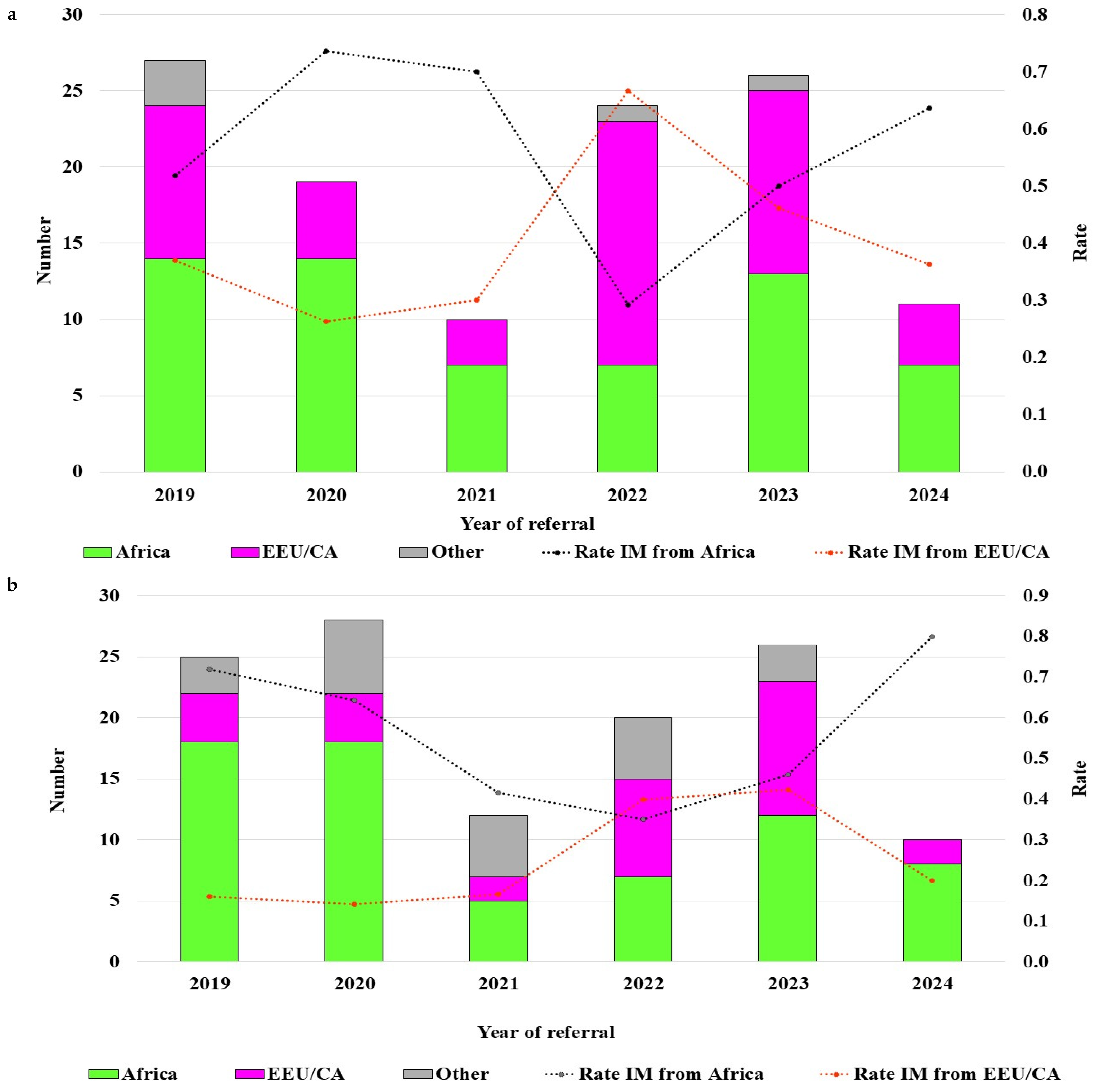

3.1. Epidemiology

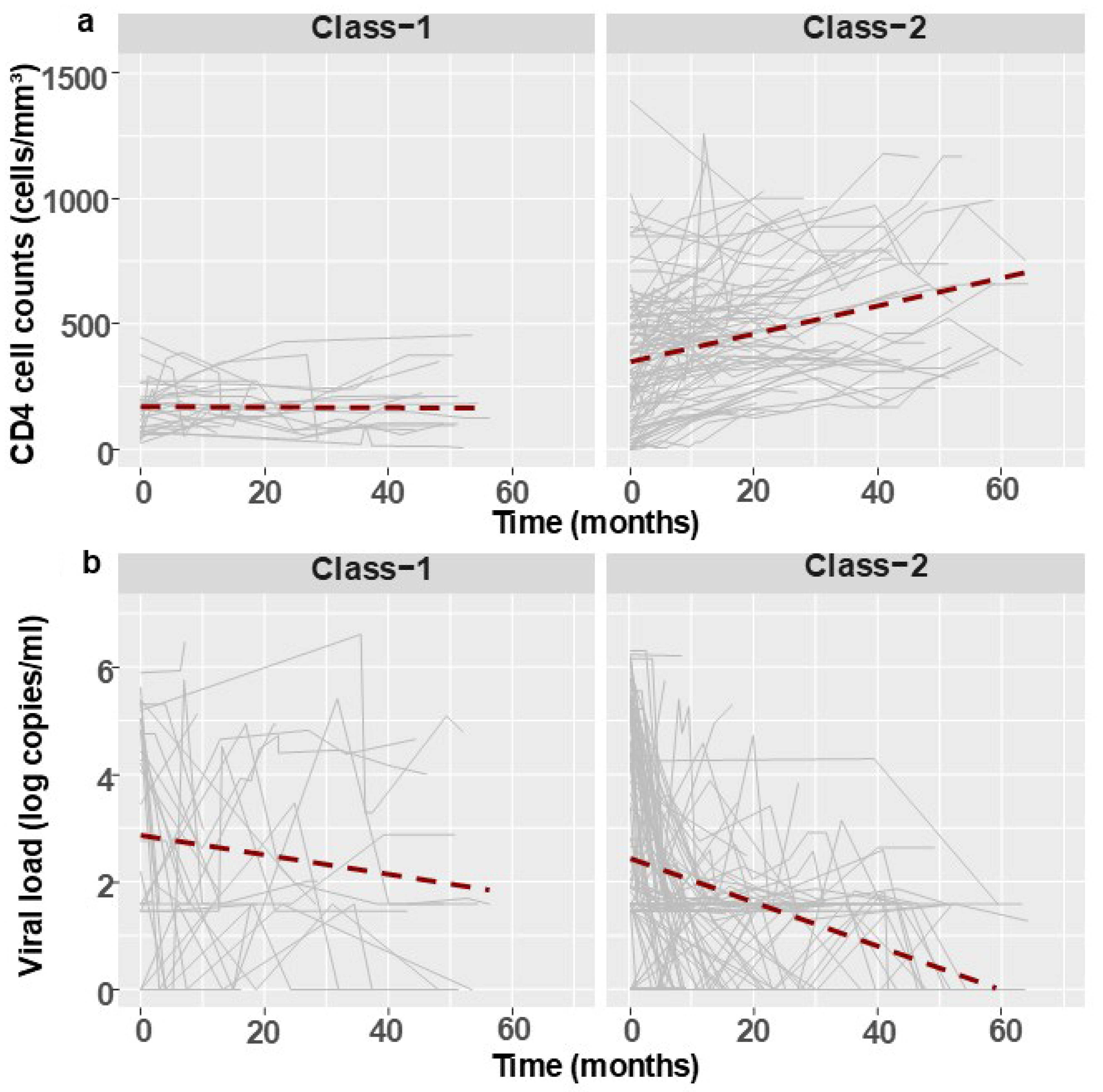

3.2. Follow-Up Analysis

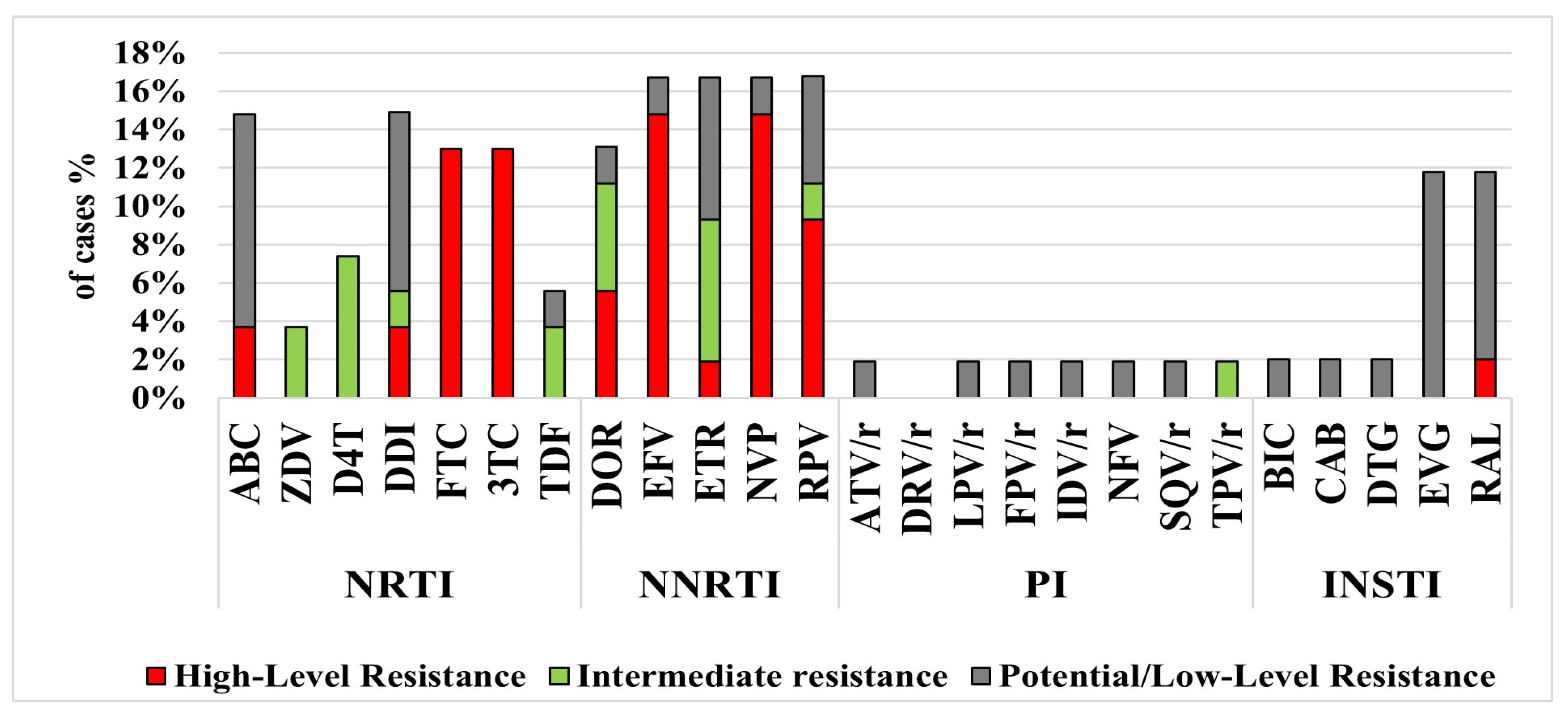

3.3. Resistance Mutations, Subtyping and Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMs | irregular migrants |

| HIV-1, HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| PPP | public–private partnership |

| VL | viral load |

| ART | antiretroviral treatment |

| NRTIs | nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| NNRTIs | non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| PIs | non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| RTs | non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| PLHIV | people living with HIV-1 |

| MoH | people living with HIV-1 |

| NHRL | National HIV Reference Laboratory |

| DRM | drug resistance mutation |

| VF | viral failure |

| Hetero | heterosexual |

| MSM | men who have sex with men |

| IVDUs | intravenous drug users |

| ATV | atazanavir |

| RTV | ritonavir |

| LPV | lopinavir |

| TDF | tenofovir disoproxil fumarate |

| 3TC | lamivudine |

| FTC | emtricitabine |

| ZDV | zidovudine |

| EFV | efavirenz |

| NVP | nevirapine |

| STR | single tablet regimen |

| INSTIs | integrase inhibitors |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PR | protease |

| RT | reverse transcriptase |

| IN | integrase |

| RIP | Recombinant Identification Program |

| CRFs | circulating recombinant forms |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| EEU/CA | Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| GTs | genotyping tests |

| US | United States |

| DTG | dolutegravir |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

References

- Migrants Being Left Behind by the HIV Response in Europe. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/news/jan-2024/migrants-being-left-behind-hiv-response-europe (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Krankowska, D.C.; Lourida, P.; Quirke, S.M.; Woode Owusu, M.; Weis, N.; EACS/WAVE Migrant Women Working Group. Barriers to HIV testing and possible interventions to improve access to HIV healthcare among migrants, with a focus on migrant women: Results from a European survey. HIV Med. 2024, 25, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bil, J.P.; Zuure, F.R.; Alvarez-Del Arco, D.; Prins, J.M.; Brinkman, K.; Leyten, E.; van Sighem, A.; Burns, F.; Prins, M. Disparities in access to and use of HIV-related health services in the Netherlands by migrant status and sexual orientation: A cross-sectional study among people recently diagnosed with HIV infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Migrants in an Irregular Situation: Access to Health Care in 10 European Union Member States; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC. HIV and Migrants. Monitoring the Implementation of the Dublin Declaration on Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia: 2022 Progress Report; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McNairy, M.L.; El-Sadr, W.M. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV transmission: What will it take? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Meyers, K.; Oh, D.-Y.; Hou, J.; Xia, W.; Su, B.; Wang, N.; Lu, X.; et al. From CD4-Based Initiation to Treating All HIV-Infected Adults Immediately: An Evidence-Based Meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Population of Israel on the Eve of 2024; Central Bureau of Statistics: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023.

- Population & Immigration Authority. Statistics of Foreigners in Israel-2023 Summary; Population & Immigration Authority: Jerusalem, Israel, 2024.

- Chemtob, D.; Levy, I.; Kaufman, S.; Averick, N.; Krauss, A.; Turner, D. Drop-out of medical follow-up among people living with HIV in Tel-Aviv area. AIDS Care 2022, 34, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemtob, D.; Rich, R.; Harel, N.; Averick, N.; Schwartzberg, E.; Yust, I.; Maayan, S.; Grotto, I.; Gamzu, R. Ensuring HIV care to undocumented migrants in Israel: A public-private partnership case study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2019, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selik, R.; Mokotoff, E.; Branson, B.; Owen, S.; Whitmore, S.; Hall, H. Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection-United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014, 63, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mor, O.; Gozlan, Y.; Wax, M.; Mileguir, F.; Rakovsky, A.; Noy, B.; Mendelson, E.; Levy, I. Evaluation of the RealTime HIV-1, Xpert HIV-1, and Aptima HIV-1 Quant Dx Assays in Comparison to the NucliSens EasyQ HIV-1 v2.0 Assay for Quantification of HIV-1 Viral Load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 3458–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European AIDS Clinical Society. Available online: https://eacs.sanfordguide.com/en/eacs-hiv/art/eacs-virological-failure (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-arv/virologic-failure-and-antiretroviral (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Cutrell, J.; Bedimo, R. Single-Tablet Regimens in the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. Fed. Pract. 2016, 33, 24S–30S. [Google Scholar]

- Moscona, R.; Ram, D.; Wax, M.; Bucris, E.; Levy, I.; Mendelson, E.; Mor, O. Comparison between next-generation and Sanger-based sequencing for the detection of transmitted drug-resistance mutations among recently infected HIV-1 patients in Israel, 2000–2014. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HIVDB HIV Drug Resistance Database. Available online: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/ (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Tang, M.W.; Liu, T.F.; Shafer, R.W. The HIVdb system for HIV-1 genotypic resistance interpretation. Intervirology 2012, 55, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust-Lima, C.; Philipps, V.; Liquet, B. Estimation of extended mixed models using latent classes and latent processes: The R. package lcmm. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 78, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitlmann, N.; Gunsenheimer-Bartmeyer, B.; Santos-Hövener, C.; Kollan, C.; An der Heiden, M.; ClinSurv Study Group. CD4-cell counts and presence of AIDS in HIV-positive patients entering specialized care-a comparison of migrant groups in the German ClinSurv HIV Cohort Study, 1999–2013. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, G.R.; Furrer, H.; Ledergerber, B.; Perrin, L.; Opravil, M.; Vernazza, P.; Cavassini, M.; Bernasconi, E.; Rickenbach, M.; Hirschel, B.; et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.; Levy, I.; Elbirt, D.; Shahar, E.; Olshtain-Pops, K.; Elinav, H.; Chowers, M.; Istomin, V.; Riesenberg, K.; Geva, D.; et al. Factors Associated with Virological Failure in First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy in Patients Diagnosed with HIV-1 between 2010 and 2018 in Israel. Viruses 2023, 15, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Price List. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/dynamiccollectors/moh-price-list?skip=0 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Wagner, T.; Zuckerman, N.S.; Halperin, T.; Chemtob, D.; Levy, I.; Elbirt, D.; Shachar, E.; Olshtain-Pops, K.; Elinav, H.; Chowers, M.; et al. Epidemiology and Transmitted HIV-1 Drug Resistance among Treatment-Naïve Individuals in Israel, 2010–2018. Viruses 2021, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, R.; Lessells, R.; Hauser, A.; Kouyos, R.; Davies, M.-A.; Egger, M.; Wandeler, G. HIV drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: Public health questions and the potential role of real-world data and mathematical modelling. J. Virus Erad. 2018, 4, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesham, I.; Parikh, U.M.; Mellors, J.W.; Joseph Davey, D.L.; Heffron, R.; Palanee-Phillips, T.; Bosman, S.L.; Beksinska, M.; Smit, J.; Ahmed, K.; et al. High Levels of Pretreatment HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations Among South African Women Who Acquired HIV During a Prospective Study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 91, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosli, T.; Hossmann, S.; Ingle, S.M.; Okhai, H.; Kusejko, K.; Mouton, J.; Bellecave, P.; van Sighem, A.; Stecher, M.; d Arminio Monforte, A.; et al. HIV-1 drug resistance in people on dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy: A collaborative cohort analysis. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e733–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, A. Israel’s Demography 2023: Declining Fertility, Migration, and Mortality. Taub Center For Social Policy Studies in Israel. Jerusalem, December 2023. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Demography-ENG-2023-2.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Migration Data Relevant for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/migration-data-relevant-covid-19-pandemic#key-migration-trends (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- ECDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2023; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. An Updated Protocol of HIV Early Detection in Pregnant Women. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/pages/06092022-02 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Grossman, Z.; Avidor, B.; Mor, Z.; Chowers, M.; Levy, I.; Shahar, E.; Riesenberg, K.; Sthoeger, Z.; Maayan, S.; Shao, W.; et al. A Population-Structured HIV Epidemic in Israel: Roles of Risk and Ethnicity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrell, A.G.; Schapiro, J.M.; Perno, C.F.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Quercia, R.; Patel, P.; Polli, J.W.; Dorey, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Exploring predictors of HIV-1 virologic failure to long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine: A multivariable analysis. AIDS 2021, 35, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.; Zhao, X.Z.; Burke, T.R.; Hughes, S.H. Efficacies of Cabotegravir and Bictegravir against drug-resistant HIV-1 integrase mutants. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkheir, N.; Dominic, C.; Price, A.; Carter, J.; Ahmed, N.; Moore, D.A.J. HIV in Latin American migrants in the UK: A neglected population in the 95-95-95 targets. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Get Tested for HIV. Available online: https://www.gov.il/en/service/hiv-testing-centers (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Baggaley, R.F.; Zenner, D.; Bird, P.; Hargreaves, S.; Griffiths, C.; Noori, T.; Friedland, J.S.; Nellums, L.B.; Pareek, M. Prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in migrants in Europe in the era of universal health coverage. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e876–e884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV and Migrants. Monitoring Implementation of the Dublin Declaration on Partnership to Fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia: 2018 Progress Report; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.A. Displacement and disease: HIV risks and healthcare gaps among refugee populations. Venereology 2025, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 Observatory Report. Unheard, Unseen, and Untreated: Health Inequalities in Europe Today; Médecins du Monde: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2021-Observatory-Report.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Nöstlinger, C.; Cosaert, T.; Landeghem, E.V.; Vanhamel, J.; Jones, G.; Zenner, D.; Jacobi, J.; Noori, T.; Pharris, A.; Smith, A.; et al. HIV among migrants in precarious circumstances in the EU and European Economic Area. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e428–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Overall, N = 238 |

|---|---|

| Age at referral, median (IQR), years | 40 (35–49) |

| HIV-1 status | |

| Previously known with HIV-1, n (%) | 143 (60) |

| Previously known abroad | 23 (23/143) |

| Previously known and treated abroad | 81 (81/143) |

| Previously treated in Israel | 39 (39/143) |

| Newly identified in Israel, n (%) | 51 (21) |

| Previous status unknown, n (%) | 44 (19) |

| Time from diagnosis to PPP referral, median (IQR), months | 6 (6–12) |

| Sex | |

| Female, n (%) | 117 (49) |

| Male, n (%) | 121 (51) |

| Birthplace | |

| Africa, n (%) | 130 (55) |

| EEU/CA, n (%) | 81 (34) |

| Other, n (%) | 27 (11) |

| Transmission | |

| Hetero from Africa, n (%) | 128 (54) |

| Hetero from EEU/CA, n (%) | 44 (18) |

| Hetero from other regions *, n (%) | 8 (3.4) |

| MSM, n (%) | 27 (11) |

| IVDU, n (%) | 13 (5.5) |

| MTCT, n (%) | 1 (0.4) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 17 (7.1) |

| CD4 at referral, median (IQR), cells/mm3 | 286 (97–518) |

| CD4 by groups | |

| <200, n (%) | 95 (40) |

| 200–350, n (%) | 42 (18) |

| ≥350, n (%) | 101 (42) |

| VL, (N = 190) at referral, median (IQR), log copies/mL | 2.80 (1.51–5.09) |

| Pregnancy, (N = 117), n (%) | 15 (13) |

| AIDS defining disease upon referral, n (%) | 52 (22) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wagner, T.; Mor, Z.; Dickstein, Y.; Turner, D.; Kedem, E.; Levy, I.; Wieder-Finesod, A.; Elinav, H.; Eddin, I.N.; Olshtain-Pops, K.; et al. Accessing HIV Care to Irregular Migrants in Israel, 2019–2024. Viruses 2025, 17, 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121566

Wagner T, Mor Z, Dickstein Y, Turner D, Kedem E, Levy I, Wieder-Finesod A, Elinav H, Eddin IN, Olshtain-Pops K, et al. Accessing HIV Care to Irregular Migrants in Israel, 2019–2024. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121566

Chicago/Turabian StyleWagner, Tali, Zohar Mor, Yaakov Dickstein, Dan Turner, Eynat Kedem, Itzchak Levy, Anat Wieder-Finesod, Hila Elinav, Ibrahim Nasser Eddin, Karen Olshtain-Pops, and et al. 2025. "Accessing HIV Care to Irregular Migrants in Israel, 2019–2024" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121566

APA StyleWagner, T., Mor, Z., Dickstein, Y., Turner, D., Kedem, E., Levy, I., Wieder-Finesod, A., Elinav, H., Eddin, I. N., Olshtain-Pops, K., Elbirt, D., Smolyakov, R., Istomin, V., Wax, M., Gozlan, Y., & Mor, O. (2025). Accessing HIV Care to Irregular Migrants in Israel, 2019–2024. Viruses, 17(12), 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121566