Pericarditis in a Child with COVID-19 Complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae Sepsis: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

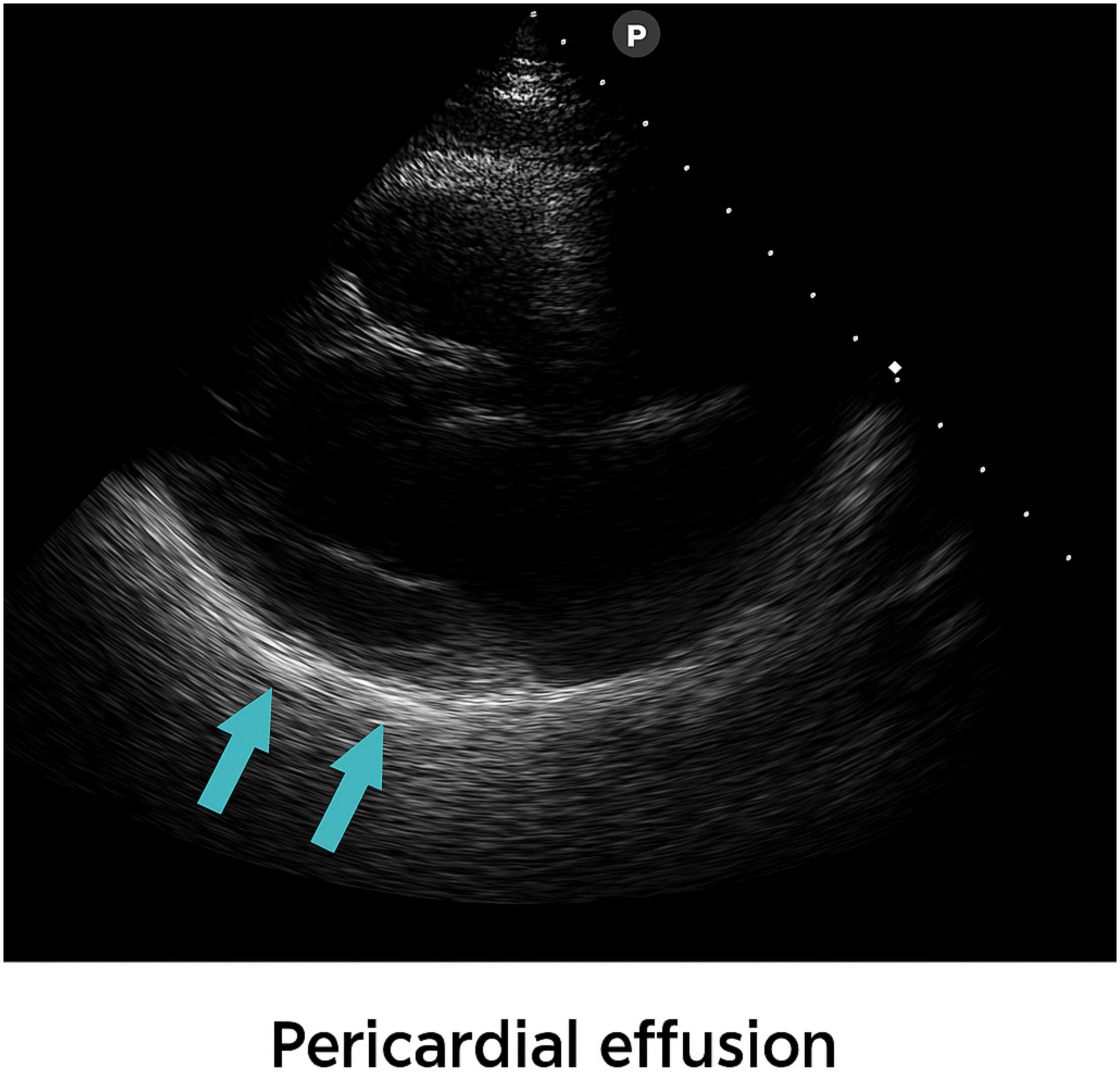

2. Case Presentation

3. Treatment and Outcome

4. Discussion

- The pathogenetic relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and secondary pneumococcal infection

- Integrated Management of Co-infections

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of COVID-19: Interim Guidance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://iris.who.int/items/66694555-22f6-49c4-be18-f740fc15abb5 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Goldstein, B.; Giroir, B.; Randolph, A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: Definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 6, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazio, M.; Adler, Y. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Y.; Charron, P.; Imazio, M.; Badano, L.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Bogaert, J.; Brucato, A.; Gueret, P.; Klingel, K.; Lionis, C.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2921–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, K.C.; Heresi, G.P.; Chang, M.L. SARS-CoV-2 and Streptococcus pneumoniae Coinfection in a Previously Healthy Child. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2021, 2021, 8907944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katfy, M.; Kettani, A.E.; Katfy, K.; Diawara, I.; Nzoyikorera, N.; Boussetta, S.; Abdallaoui, M.S.; Bousfiha, A.A. Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 among patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae in Casablanca. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 755. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12879-025-10953-z (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, D.; De Groot, R.; Hermans, P.W. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: The key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simell, B.; Auranen, K.; Käyhty, H.; Goldblatt, D.; Dagan, R.; O’brien, K.L.; Pneumococcal Carriage Group (PneumoCarr). The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkwah, S.; Somda, N.S.; Mahazu, S.; Donkor, E.S. Pneumococcal serotypes and their association with death risk in invasive pneumococcal disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1566502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.Y.; Nahm, M.H.; Moseley, M.A. Clinical implications of pneumococcal serotypes. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, A.I.; Rafila, A.; Dorobăț, O.M.; Mihai, A.; Popescu, G.A. invasive pneumococcal disease–prevalent serotypes and antimicrobial resistance with its impact on the antimicrobial therapy. A 2011-2017 retrospective study at the national institute for infectious diseases (niid) ‘prof. Dr. Matei Balş’. Comunicări Orale Tineri Med. 2017, 62, 3–4. Available online: https://www.srm.ro/media/2018/07/volum62.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Lixandru, R.I.; Falup-Pecurariu, C.; Bleotu, L.; Mercas, A.; Leibovitz, E.; Dagan, R.; Greenberg, D.; Falup-Pecurariu, O. Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotypes and Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns Middle Ear Fluid Isolates During Acute Otitis Media and Nasopharyngeal Isolates During Community-acquired Alveolar Pneumonia in Central Romania. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugulete, G.; Merișescu, M.M.; Pavelescu, C.; Luminos, M.L. Rare fatal case of purpura fulminans due to pneumococcal sepsis. Germs 2024, 14, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoicescu, S.M.; Mohora, R.; Luminos, M.; Merisescu, M.M.; Jugulete, G.; Nastase, L. Presepsin—New marker of sepsis: Romanian NICU experience. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 3008–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.I.; Hsueh, P.R. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, O.V.; Holden, K.A.; Turtle, L.; Pollock, L.; Fairfield, C.J.; Drake, T.M.; Seth, S.; Egan, C.; Hardwick, H.E.; Halpin, S.; et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: Prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ 2020, 370, m3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matic, K.M. SARS-CoV-2 and MIS-C. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2021, 51, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, Y.; Lichter, Y.; Taieb, P.; Banai, A.; Hochstadt, A.; Merdler, I.; Oz, A.G.; Rothschild, E.; Baruch, G.; Peri, Y.; et al. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in COVID-19. Circulation 2020, 142, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Nassif, T.H.; Daou, K.N.; Tannoury, T.; Majdalani, M. Cardiac involvement in a child post COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e242084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugulete, G.; Merișescu, M.M.; Bastian, A.E.; Zurac, S.; Stoicescu, S.M.; Luminos, M.L. Severe Form of A1H1 Influenza in a Child—Case Presentation. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 26, 387–391. Available online: https://www.rjlm.ro/system/revista/48/387-391.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, N.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Luo, X.; Fukuoka, T.; et al. Effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin for children with severe COVID-19. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugulete, G.; Pacurar, D.; Pavelescu, M.L.; Safta, M.; Gheorghe, E.; Borcoș, B.; Pavelescu, C.; Oros, M.; Merișescu, M. Clinical and evolutionary features of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Children 2022, 9, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, S.; Faramarzi, S.; Zandi, M.; Shahbahrami, R.; Jafarpour, A.; Rezayat, S.A.; Pakzad, I.; Abdi, F.; Malekifar, P.; Pakzad, R. Bacterial coinfection among COVID-19 patient groups. New Microbes New Infect. 2021, 43, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; McGarvey, J.; Montgomery, V.; Gharpure, V.P.; Kashyap, R.; Walkey, A.; Bansal, V.; Boman, K.; Kumar, V.K.; Kissoon, N. Prevalence of sepsis as defined by phoenix sepsis definition among children with COVID-19. Hosp. Pediatr. 2025, 15, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhou, G. Progress on diagnosis and treatment of MIS-C. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1551122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merișescu, M.M.; Luminos, M.L.; Pavelescu, C.; Jugulete, G. Clinical Features and Outcomes of the Association of Co-Infections in Children with Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza during the 2022-2023 Season: A Romanian Perspective. Viruses 2023, 15, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, P.; Sedighian, H.; Behzadi, E.; Kachuei, R.; Fooladi, A.A.I. Interaction Between SARS-CoV-2 and Pathogenic Bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, T.; Chonmaitree, T. Importance of respiratory viruses in acute otitis media. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, B.; Ding, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Y.; Zeng, D.; Su, R. Clinical observation of otitis media secretory during COVID-19. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadraga, A.; Korniychuk, O.; Nadraga, M.I. Viral–bacterial interactions: Mechanisms and significance during COVID-19. Galician Med. J. 2025, 32, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Weng, R.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Tie, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Dual threat: Susceptibility mechanisms and treatment strategies for COVID-19 and bacterial coinfections. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarczak, D.; Kluge, S.; Nierhaus, A. Use of Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Sepsis Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hospital Day | 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (/mm3) | 7500 | 7700 | 10,430 | 17,900 | 6000–17,000 |

| Neutrophils (/mm3) | 2100 | 2150 | 3160 | 4200 | 1800–8000 |

| Lymphocytes (/mm3) | 4000 | 4300 | 6290 | 12,100 | 3000–9500 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.7 | 9.9 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 12–15 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 319 | 85 | 23 | 2 | 0–5 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 890 | 630 | 366 | 254 | 200–400 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 2.12 | 1.62 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0–0.5 |

| Troponin (ng/mL) | – | 0.03 | 0.03 | – | 0–0.04 |

| Hospital Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever (>38 °C) |  | |||||||||

| Chest pain |  | |||||||||

| PCR Biofire | S.pneumoniae Serotype 19 F | |||||||||

| Otic secretion | Sampling | S.pneumoniae | ||||||||

| Pericardial fluid | 0.5 cm | 0.3 cm | ||||||||

| Remdesivir |  | |||||||||

| Antibiotics | Ceftriaxone | Meropenem + Linezolid | ||||||||

| Corticosteroid Dexamethasone | - | - | 6 mg/zi | 6 mg/zi | 4 mg/zi | 4 mg/zi | 2 mg/zi | 2 mg/zi | - | - |

| IVIG |  | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merișescu, M.M.; Oroș, M.; Jugulete, G.; Borcoș, B.; Răduț, L.M.; Totoianu, A.; Dragomirescu, A.O. Pericarditis in a Child with COVID-19 Complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae Sepsis: A Case Report. Viruses 2025, 17, 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121567

Merișescu MM, Oroș M, Jugulete G, Borcoș B, Răduț LM, Totoianu A, Dragomirescu AO. Pericarditis in a Child with COVID-19 Complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae Sepsis: A Case Report. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121567

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerișescu, Mădălina Maria, Mihaela Oroș, Gheorghiță Jugulete, Bianca Borcoș, Larisa Mirela Răduț, Alexandra Totoianu, and Anca Oana Dragomirescu. 2025. "Pericarditis in a Child with COVID-19 Complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae Sepsis: A Case Report" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121567

APA StyleMerișescu, M. M., Oroș, M., Jugulete, G., Borcoș, B., Răduț, L. M., Totoianu, A., & Dragomirescu, A. O. (2025). Pericarditis in a Child with COVID-19 Complicated by Streptococcus pneumoniae Sepsis: A Case Report. Viruses, 17(12), 1567. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121567