Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Eurasian Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus with MGF505-2R Gene Deletion in Piglets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Virus and Cells

2.3. Evaluation of Pathogenicity of ASFV-ΔMGF505-2R

2.4. Anesthesia Procedure

2.5. Immune Response Analysis

2.6. The Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (q-PCR) Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pathogenicity of ASFV-ΔMGF505-2R in Piglets

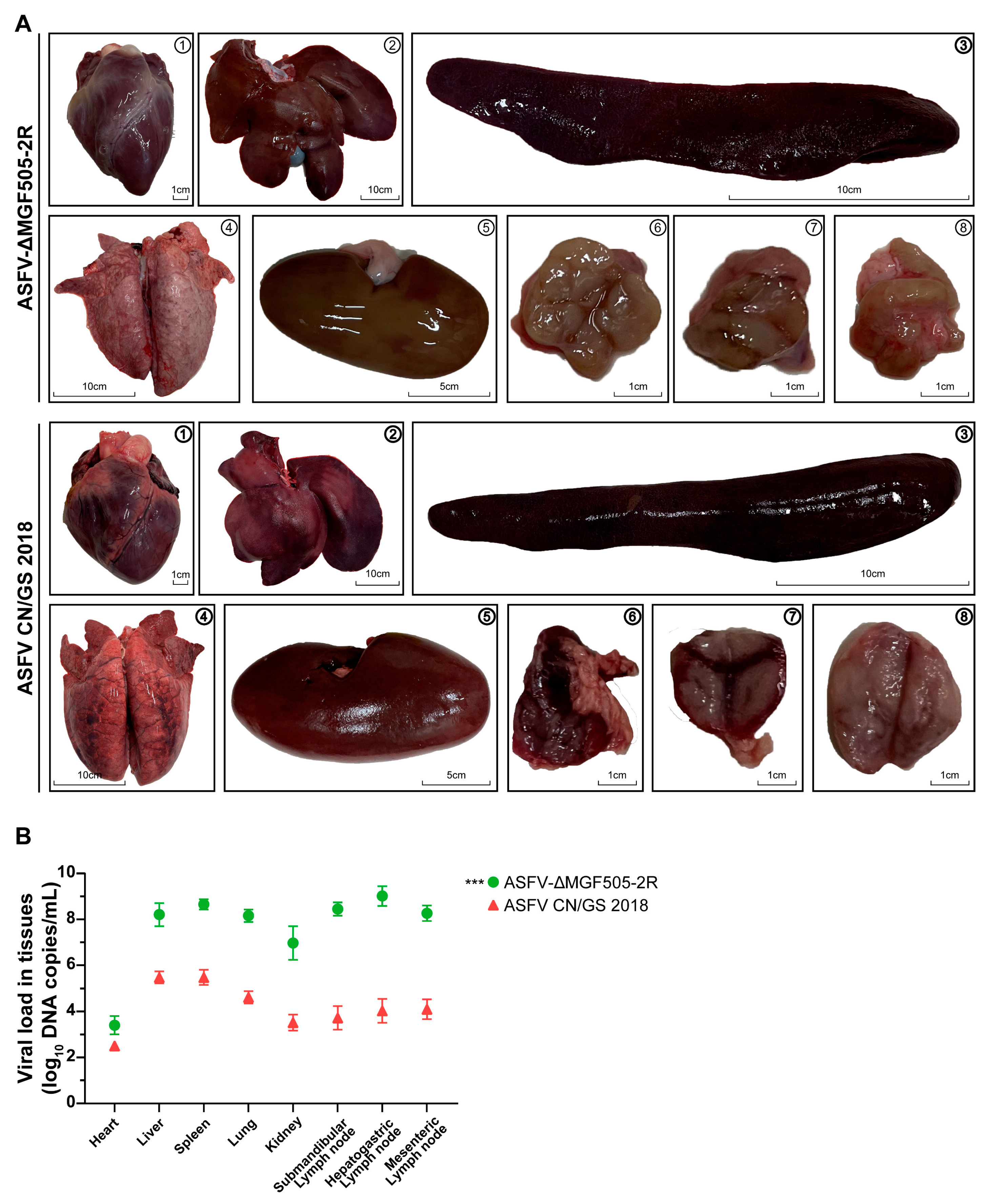

3.2. ASFV-ΔMGF505-2R Induced Slight Pathological Damage in Organs

3.3. ASFV-ΔMGF505-2R Group Showed Only Mild to Moderate Histological Changes

3.4. Immune Response Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Progress in Live Attenuated Vaccine Development

4.2. ASFV-ΔMGF505-2R Was Largely Attenuated in Piglets

4.3. Correlation Between Antibody Levels and Survival Rates

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASFV | African swine fever virus |

| LAVs | Live attenuated vaccines |

| MGF | multigene family |

| dpi | days post-inoculation |

References

- Spinard, E.; O’Donnell, V.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Davis, C.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Espinoza, N.; Valladares, A.; Borca, M.V.; Gladue, D.P. Full genome sequence for the African swine fever virus outbreak in the Dominican Republic in 1980. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubálek, Z.; Rudolf, I. Tick-borne viruses in Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajko-Nenow, P.; Batten, C. Genotyping of African Swine Fever Virus. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2503, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, I.; Alonso, C. African Swine Fever Virus: A Review. Viruses 2017, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter-Louis, C.; Conraths, F.J.; Probst, C.; Blohm, U.; Schulz, K.; Sehl, J.; Fischer, M.; Forth, J.H.; Zani, L.; Depner, K.; et al. African Swine Fever in Wild Boar in Europe—A Review. Viruses 2021, 13, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zheng, H. Insights and progress on epidemic characteristics, pathogenesis, and preventive measures of African swine fever virus: A review. Virulence 2025, 16, 2457949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, N.T.A.; Vu, X.D.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, K.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Bui, T.T.N.; et al. Molecular profile of African swine fever virus (ASFV) circulating in Vietnam during 2019–2020 outbreaks. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathuranga, K.; Lee, J.S. African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV): Immunity and Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Xu, W.; Xie, T.; Wang, D.; Peng, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Interactome between ASFV and host immune pathway proteins. mSystems 2023, 8, e0047123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, N.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fang, Z.; An, H.; Liu, S.; Weng, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, G. From hemorrhage to apoptosis: Understanding the devastating impact of ASFV on piglets. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0290224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, E.; Huang, L.; Ding, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, T.; et al. Highly lethal genotype I and II recombinant African swine fever viruses detected in pigs. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, H.L.X.; McVey, D.S. Recent progress on gene-deleted live-attenuated African swine fever virus vaccines. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, D.; He, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Shan, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. A seven-gene-deleted African swine fever virus is safe and effective as a live attenuated vaccine in pigs. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borca, M.V.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Pruitt, S.; Espinoza, N.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Gay, C.G.; Gladue, D.P. ASFV-G-∆I177L as an Effective Oral Nasal Vaccine against the Eurasia Strain of Africa Swine Fever. Viruses 2021, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Born, E.; Olasz, F.; Mészáros, I.; Göltl, E.; Oláh, B.; Joshi, J.; van Kilsdonk, E.; Segers, R.; Zádori, Z. African swine fever virus vaccine strain Asfv-G-∆I177l reverts to virulence and negatively affects reproductive performance. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, N.V.; Duc, N.V.; Ngoc, N.T.; Dang, V.X.; Tiep, T.N.; Nguyen, V.D.; Than, T.T.; Maydaniuk, D.; Goonewardene, K.; Ambagala, A.; et al. Genotype II Live-Attenuated ASFV Vaccine Strains Unable to Completely Protect Pigs against the Emerging Recombinant ASFV Genotype I/II Strain in Vietnam. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, V.; Holinka, L.G.; Gladue, D.P.; Sanford, B.; Krug, P.W.; Lu, X.Q.; Arzt, J.; Reese, B.; Carrillo, C.; Risatti, G.R.; et al. African Swine Fever Virus Georgia Isolate Harboring Deletions of MGF360 and MGF505 Genes Is Attenuated in Swine and Confers Protection against Challenge with Virulent Parental Virus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6048–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borca, M.V.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Pruitt, S.; Holinka, L.G.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Zhu, J.; Gladue, D.P. Development of a Highly Effective African Swine Fever Virus Vaccine by Deletion of the I177L Gene Results in Sterile Immunity against the Current Epidemic Eurasia Strain. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e02017-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, V.; Risatti, G.R.; Holinka, L.G.; Krug, P.W.; Carlson, J.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Azzinaro, P.A.; Gladue, D.P.; Borca, M.V. Simultaneous Deletion of the 9GL and UK Genes from the African Swine Fever Virus Georgia 2007 Isolate Offers Increased Safety and Protection against Homologous Challenge. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01760-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunwoo, S.Y.; García-Belmonte, R.; Walczak, M.; Vigara-Astillero, G.; Kim, D.M.; Szymankiewicz, K.; Kochanowski, M.; Liu, L.; Tark, D.; Podgórska, K.; et al. Deletion of MGF505-2R Gene Activates the cGAS-STING Pathway Leading to Attenuation and Protection against Virulent African Swine Fever Virus. Vaccines 2024, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.G.; Dang, W.; Shi, Z.W.; Ding, M.Y.; Xu, F.; Li, T.; Feng, T.; Zheng, H.X.; Xiao, S.Q. Identification of African swine fever virus MGF505-2R as a potent inhibitor of innate immunity. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.Y.; Scheenstra, M.R.; van Dijk, A.; Veldhuizen, E.J.A.; Haagsman, H.P. A new and efficient culture method for porcine bone marrow-derived M1-and M2-polarized macrophages. Vet. Immunol. Immunop 2018, 200, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weesendorp, E.; Stegeman, A.; Loeffen, W. Dynamics of virus excretion via different routes in pigs experimentally infected with classical swine fever virus strains of high, moderate or low virulence. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 133, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, R.; Ene, I.; Pavel, R. Pig Sedation and Anesthesia for Medical Research. Animal 2023, 13, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Cao, Y.; Jiao, P.; Yu, P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Zhou, X.; Qi, Y.; Sun, L.; Liu, D.; et al. Synergistic effect of the responses of different tissues against African swine fever virus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e204–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl-Ewert, J.; Friedrichs, V.; Carrau, T.; Deutschmann, P.; Blome, S. Pathology of African Swine Fever in Reproductive Organs of Mature Breeding Boars. Viruses 2023, 15, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.; Chapman, D.; Argilaguet, J.M.; Fishbourne, E.; Hutet, E.; Cariolet, R.; Hutchings, G.; Oura, C.A.; Netherton, C.L.; Moffat, K.; et al. Protection of European domestic pigs from virulent African isolates of African swine fever virus by experimental immunisation. Vaccine 2011, 29, 4593–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakobyan, S.; Bayramyan, N.; Karalyan, Z.; Izmailyan, R.; Avetisyan, A.; Poghosyan, A.; Arakelova, E.; Vardanyan, T.; Avagyan, H. The Involvement of MGF505 Genes in the Long-Term Persistence of the African Swine Fever Virus in Gastropods. Viruses 2025, 17, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koltsov, A.; Sukher, M.; Krutko, S.; Belov, S.; Korotin, A.; Rudakova, S.; Morgunov, S.; Koltsova, G. Construction of the First Russian Recombinant Live Attenuated Vaccine Strain and Evaluation of Its Protection Efficacy Against Two African Swine Fever Virus Heterologous Strains of Serotype 8. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yan, Z.; Qi, X.; Ren, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Pei, J.; Xiao, S.; et al. The Deletion of the MGF360-10L/505-7R Genes of African Swine Fever Virus Results in High Attenuation but No Protection Against Homologous Challenge in Pigs. Viruses 2025, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Yang, W.P.; Li, L.L.; Li, P.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qi, X.L.; Ren, J.J.; Ru, Y.; Niu, Q.L.; et al. African Swine Fever Virus MGF-505-7R Negatively Regulates cGAS-STING-Mediated Signaling Pathway. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 1844–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Li, D.; Weng, C. Multifunctional pMGF505-7R Is a Key Virulence-Related Factor of African Swine Fever Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 852431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, J.; Kang, L.; Huang, L.; Zhou, S.; Hu, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; He, X.; et al. pMGF505-7R determines pathogenicity of African swine fever virus infection by inhibiting IL-1β and type I IFN production. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Jiang, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Yue, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, R.; Miao, F. Deletion of the African swine fever virus E120R gene completely attenuates its virulence by enhancing host innate immunity and impairing virus release. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2555722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Chapman, D.; Jabbar, T.; Reis, A.L.; Goatley, L.; Netherton, C.L.; Taylor, G.; Montoya, M.; Dixon, L. Different routes and doses influence protection in pigs immunised with the naturally attenuated African swine fever virus isolate OURT88/3. Antivir. Res. 2017, 138, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, F.; Huang, H.; Dang, W.; Du, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Shi, Z.; Tian, H.; He, J.; Zheng, H. Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Eurasian Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus with MGF505-2R Gene Deletion in Piglets. Viruses 2025, 17, 1565. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121565

Xu F, Huang H, Dang W, Du Y, Li T, Liu H, Shi Z, Tian H, He J, Zheng H. Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Eurasian Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus with MGF505-2R Gene Deletion in Piglets. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1565. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121565

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Fan, Huaguo Huang, Wen Dang, Yu Du, Tao Li, Huanan Liu, Zhengwang Shi, Hong Tian, Jijun He, and Haixue Zheng. 2025. "Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Eurasian Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus with MGF505-2R Gene Deletion in Piglets" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1565. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121565

APA StyleXu, F., Huang, H., Dang, W., Du, Y., Li, T., Liu, H., Shi, Z., Tian, H., He, J., & Zheng, H. (2025). Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Eurasian Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus with MGF505-2R Gene Deletion in Piglets. Viruses, 17(12), 1565. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121565