Immunization of Cats against Fel d 1 Results in Reduced Allergic Symptoms of Owners

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

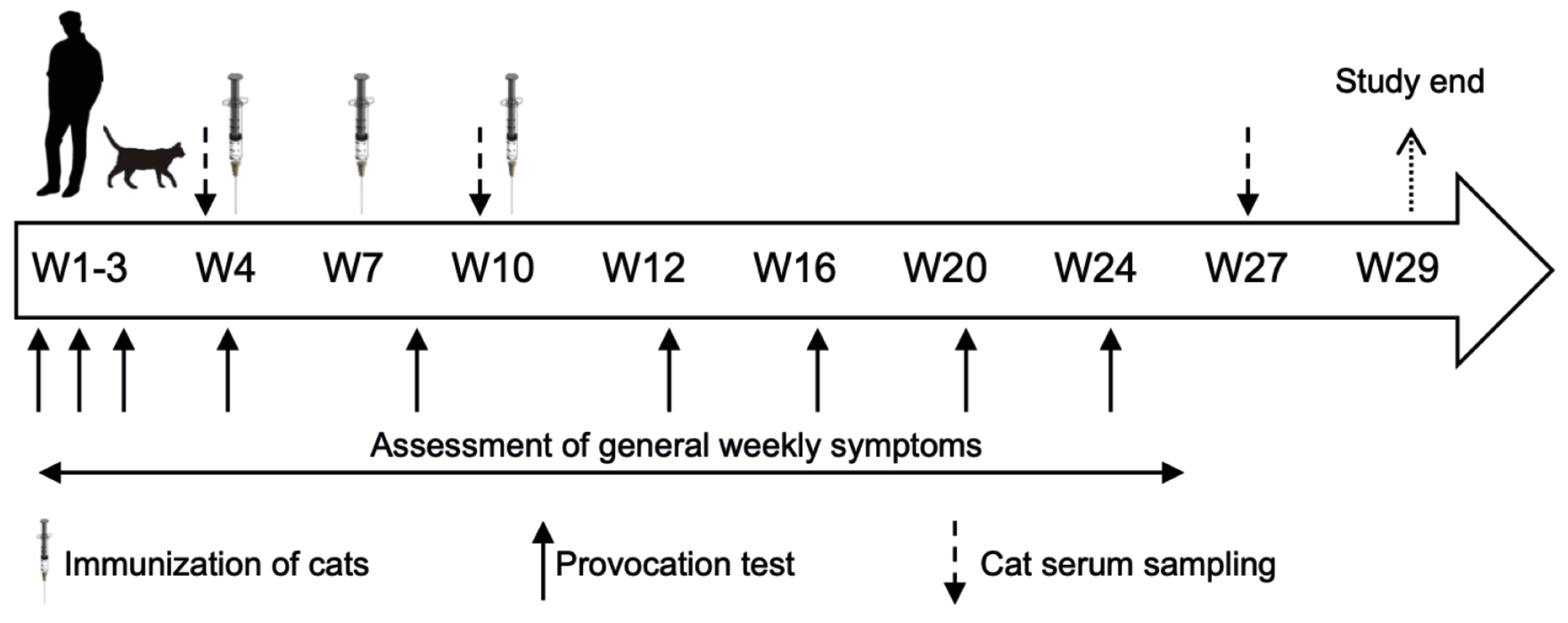

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Ethics Approvals

2.4. Study Objective

2.5. Provocation Test

2.6. General Weekly or Monthly Specific Symptoms (GWSS or GSS)

2.7. Cat Population

2.8. Vaccination of Cats

2.9. Antibody Responses in Cats

2.10. Data and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

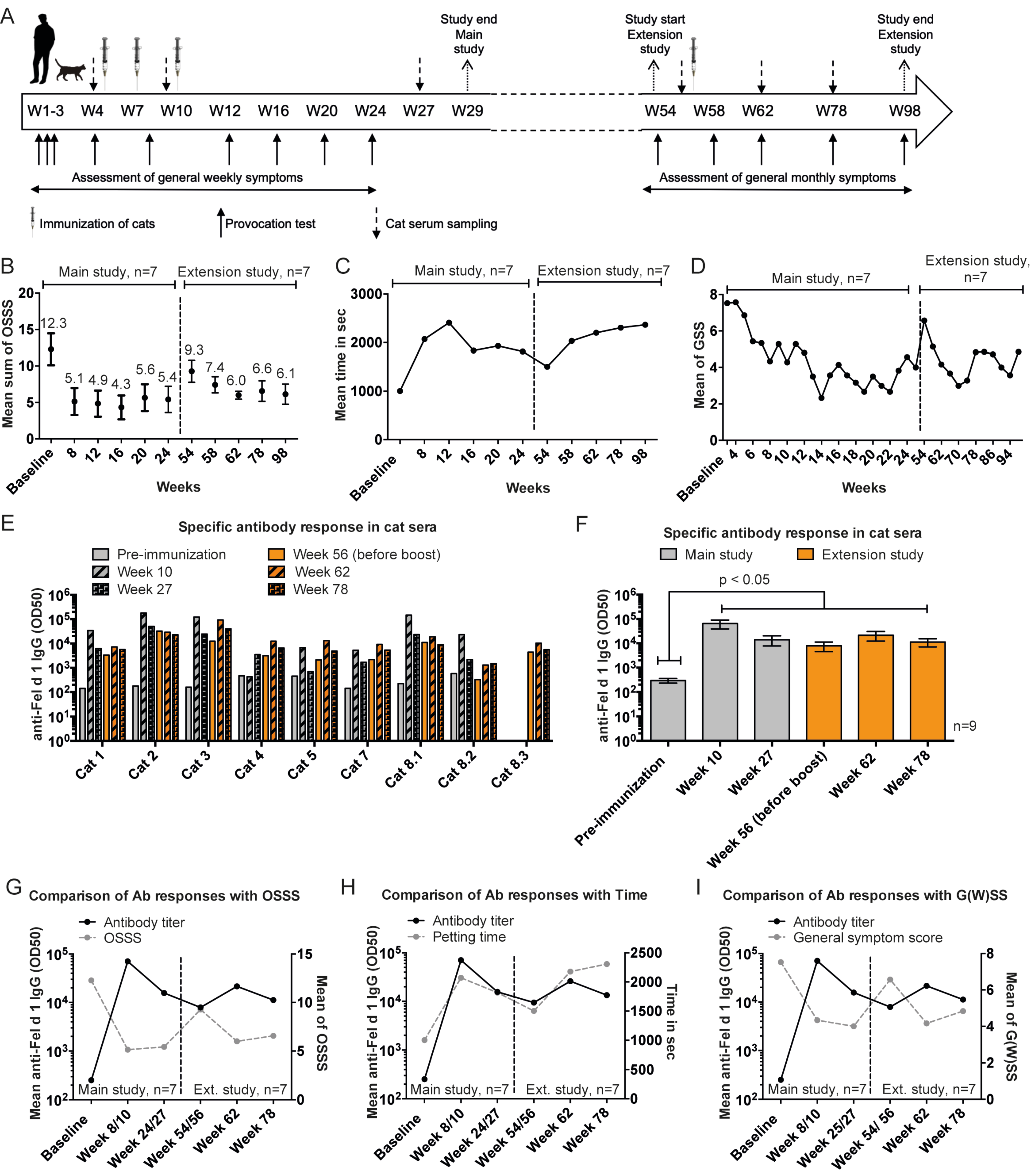

3.1. Study Design and Population

3.2. Adverse Events

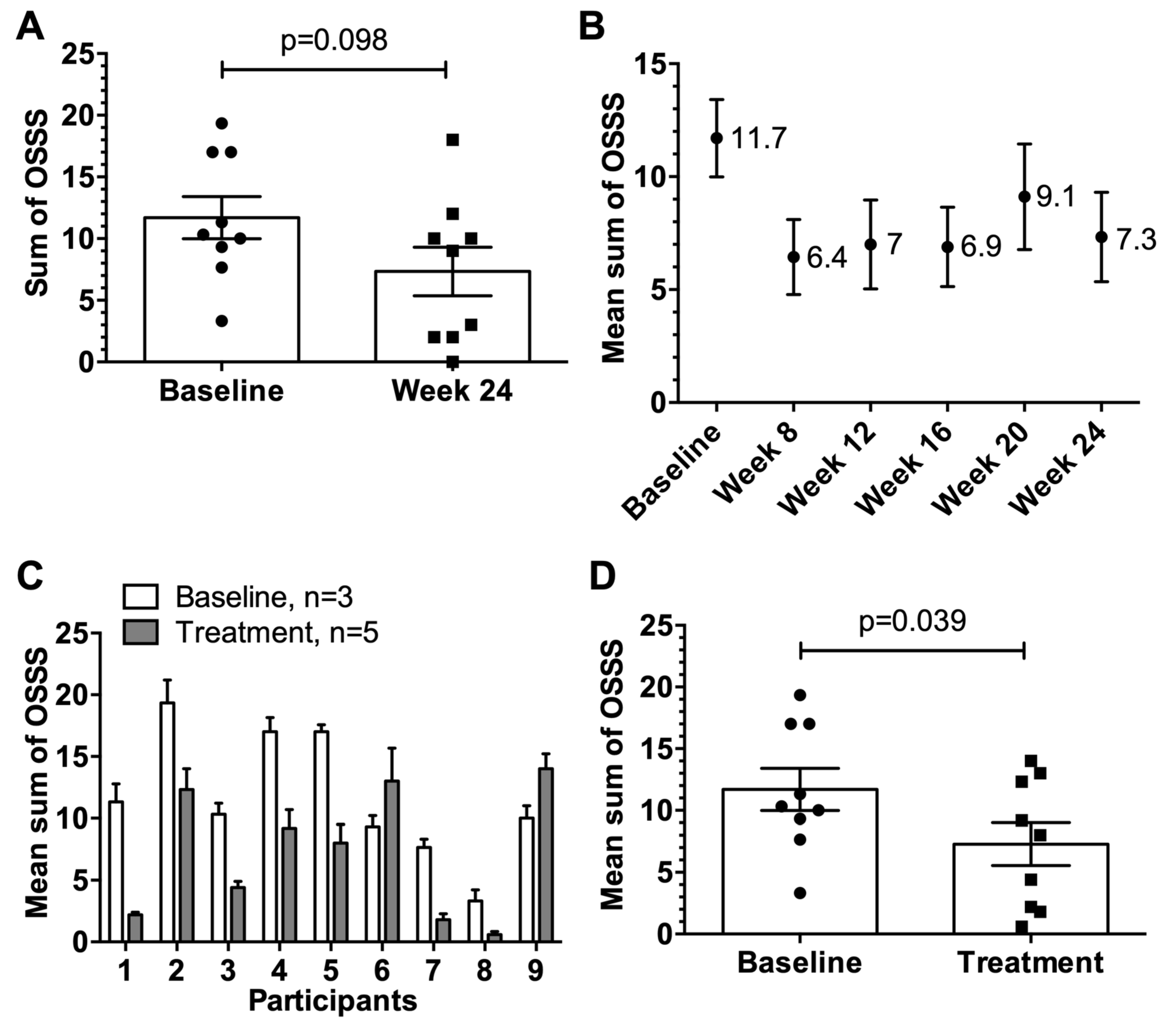

3.3. Assessment of the OSSS after Provocation

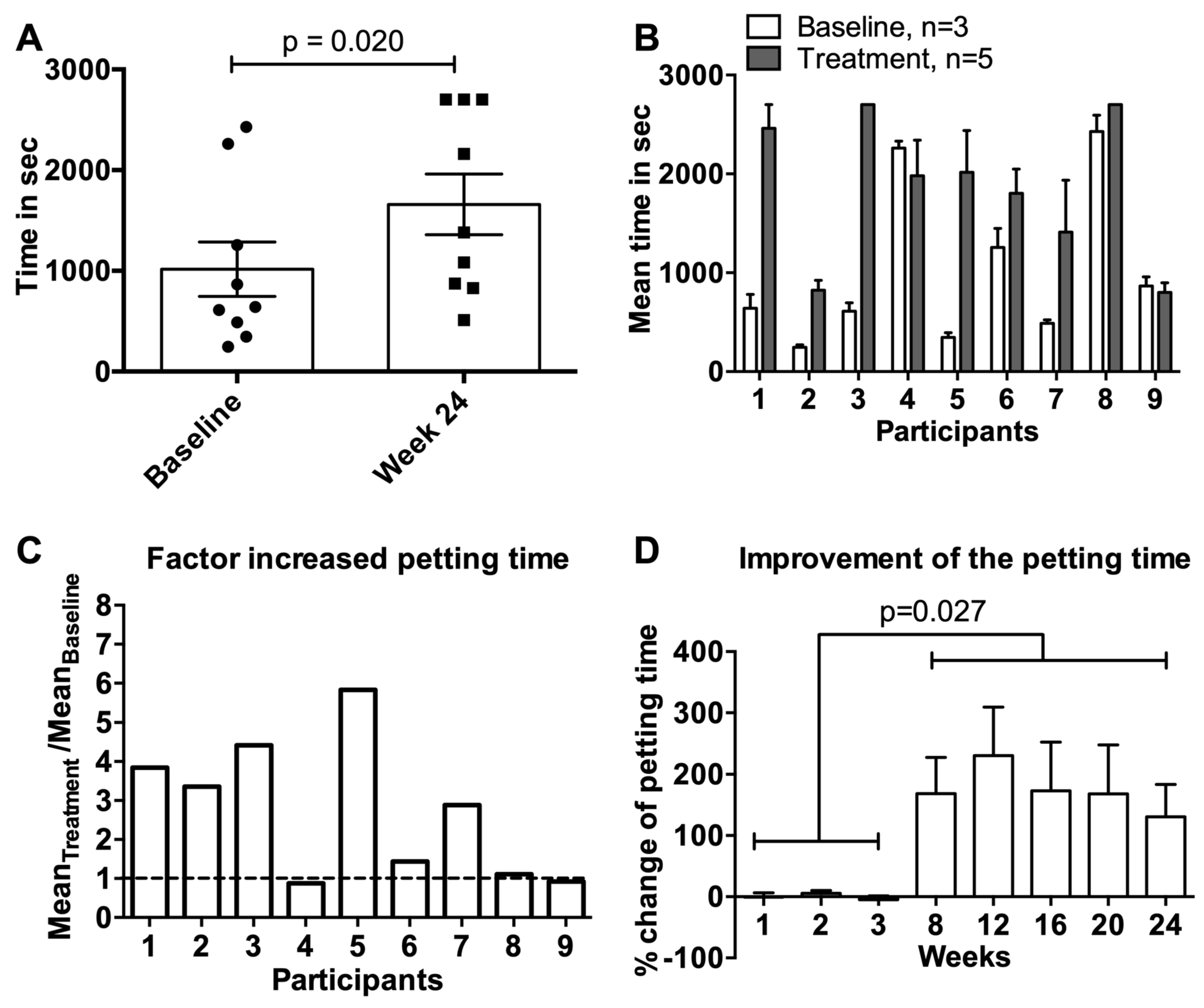

3.4. Petting Time

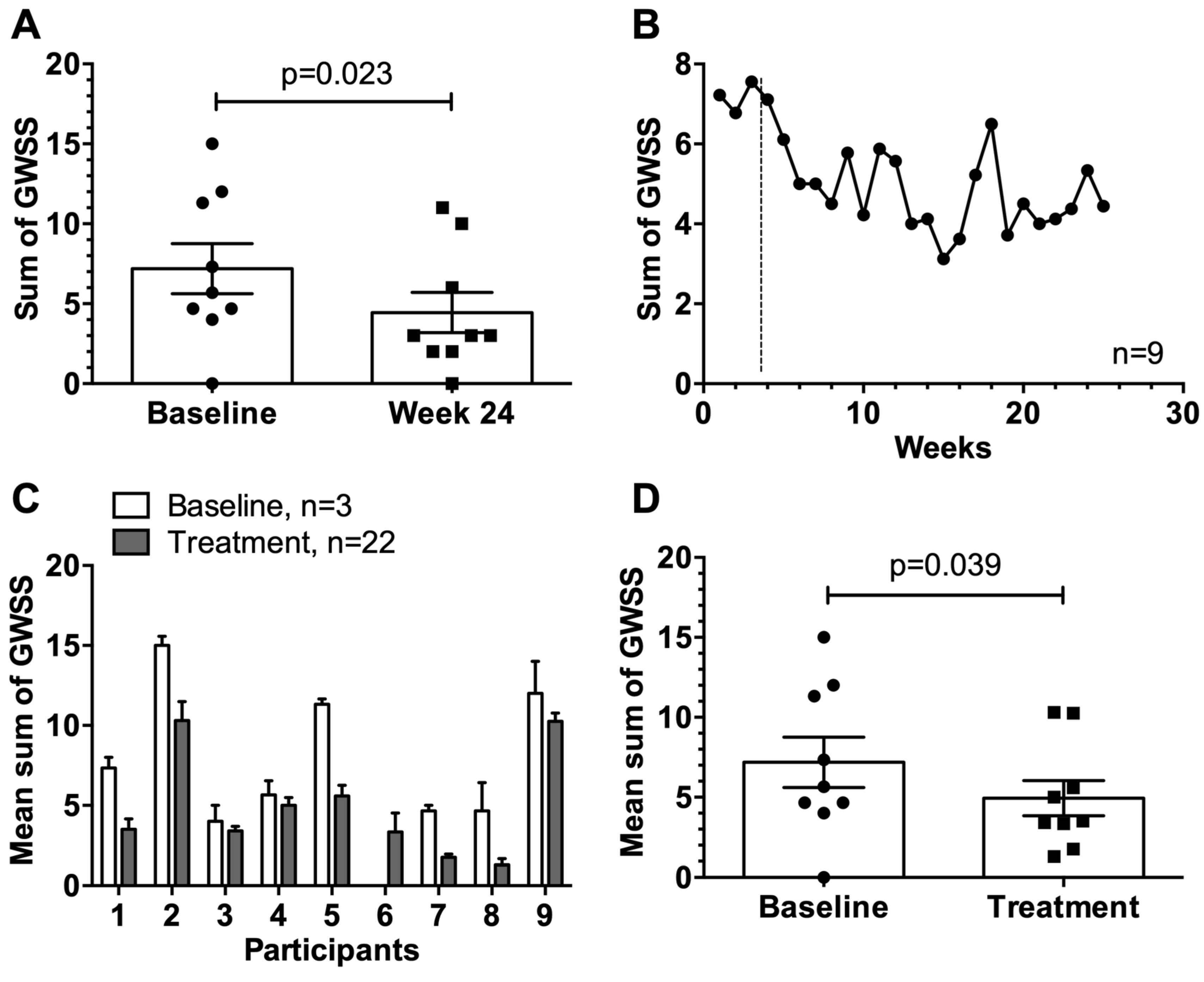

3.5. General Weekly Symptom Score

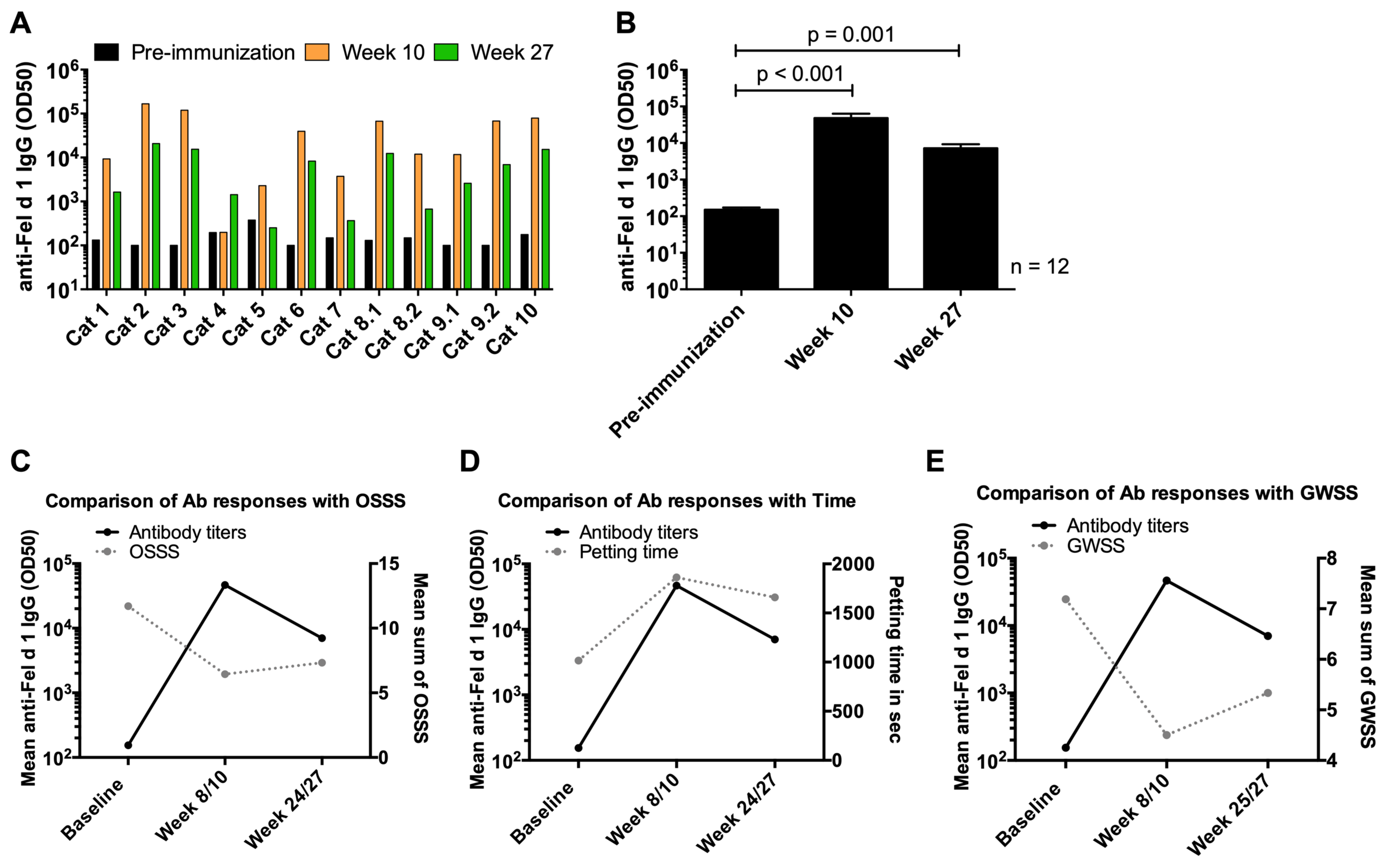

3.6. Induction of Anti-Fel d 1 IgG Antibody Responses in Cats upon Vaccination with Fel-CuMV

3.7. Data of the Extension Study

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ab | Antibody |

| AE | Adverse Event |

| CSR | Clinical Study Report |

| eCRF | Electronic Case Report Form |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Fel d 1 | Felis domesticus 1 allergen |

| Fel-CuMV | Fel d 1 - Cucumber mosaic virus-like particle conjugate vaccine |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| GSS | General montly Symptom Score |

| GWSS | General Weekly Symptom Score |

| ICH | International Conference on Harmonization |

| IEC | Independent Ethics Committee |

| ITT | Intention to Treat |

| KEK | Cantonal Ethics Committee Zürich |

| LOCF | Last Observation Carried Forward |

| LPLV | Last Patient Last Visit |

| OSSS | Organ Specific Symptom Score |

| PP | Per Protocol |

| SAE | Serious Adverse Event |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Platts-Mills, T.A.; Carter, M.C. Asthma and indoor exposure to allergens. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rance, F. Animal dander allergy in children. Arch. Pediatr. 2006, 13, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.C.; Baer, H. Allergenically active components of cat allergen extracts. J. Immunol. 1981, 127, 972–975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lowenstein, H.; Lind, P.; Weeke, B. Identification and clinical significance of allergenic molecules of cat origin. Part of the DAS 76 Study. Allergy 1985, 40, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.; O’Neil, S.E.; Hales, B.J.; Chai, T.L.; Hazell, L.A.; Tanyaratsrisakul, S.; Piboonpocanum, S.; Thomas, W.R. Two newly identified cat allergens: The von Ebner gland protein Fel d 7 and the latherin-like protein Fel d 8. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 156, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Butler, A.J.; Hazell, L.A.; Chapman, M.D.; Pomes, A.; Nickels, D.G.; Thomas, W.R. Fel d 4, a cat lipocalin allergen. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2004, 34, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsen, J.R.; Fujisawa, T.; van Hage, M.; Hedlin, G.; Hilger, C.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Matsui, E.C.; Roberts, G.; Ronmark, E.; Platts-Mills, T.A. Allergy to furry animals: New insights, diagnostic approaches, and challenges. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, J.L.; Lowell, F.C.; Bloch, K.J. Allergens of mammalian origin: Characterization of allergen extracted from cat pelts. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1973, 52, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, B.; Messaoudi, K.; Jacomet, F.; Michaud, E.; Fauquert, J.L.; Caillaud, D.; Evrard, B. An update on molecular cat allergens: Fel d 1 and what else? Chapter 1: Fel d 1, the major cat allergen. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukleja-Sokolowska, N.; Gawronska-Ukleja, E.; Zbikowska-Gotz, M.; Socha, E.; Lis, K.; Sokolowski, L.; Kuzminski, A.; Bartuzi, Z. Analysis of feline and canine allergen components in patients sensitized to pets. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2016, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, L.; Gronlund, H.; Sandalova, T.; Ljunggren, H.G.; van Hage-Hamsten, M.; Achour, A.; Schneider, G. The crystal structure of the major cat allergen Fel d 1, a member of the secretoglobin family. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37730–37735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karn, R.C. The mouse salivary androgen-binding protein (ABP) alpha subunit closely resembles chain 1 of the cat allergen Fel dI. Biochem. Genet. 1994, 32, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpin, C.; Mata, P.; Charpin, D.; Lavaut, M.N.; Allasia, C.; Vervloet, D. Fel d I allergen distribution in cat fur and skin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1991, 88, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, A.J.; Van der Brempt, X.; Soler, M.; Seguret, N.; Lucciani, P.; Charpin, D.; Vervloet, D. Cat skin as an important source of Fel d I allergen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1990, 86, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, A.D.; Birnbaum, J.; Magalon, C.; Magnol, J.P.; Lanteaume, A.; Charpin, D.; Vervloet, D. Fel d I levels in cat anal glands. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1996, 26, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Milligen, F.J.; Vroom, T.M.; Aalberse, R.C. Presence of Felis domesticus allergen I in the cat’s salivary and lacrimal glands. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1990, 92, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custovic, A.; Simpson, B.M.; Simpson, A.; Hallam, C.L.; Marolia, H.; Walsh, D.; Campbell, J.; Woodcock, A.; National Asthma Campaign Manchester Asthma and Allergy Study Group. Current mite, cat, and dog allergen exposure, pet ownership, and sensitization to inhalant allergens in adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts-Mills, T.A. The role of immunoglobulin E in allergy and asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts-Mills, T.; Vaughan, J.; Squillace, S.; Woodfolk, J.; Sporik, R. Sensitisation, asthma, and a modified Th2 response in children exposed to cat allergen: A population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet 2001, 357, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.P.; Coyle, A.J. TH2 and ’TH2-like’ cells in allergy and asthma: Pharmacological perspectives. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994, 15, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawankar, R.; Canonica, G.W.; Holgate, S.T.; Lockey, R.F.; Blaiss, M.S. WAO The White Book on Allergy; World Allergy Organization: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.C. A review of over three decades of research on cat-human and human-cat interactions and relationships. Behav. Processes 2017, 141, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuthard, D.S.; Duda, A.; Freiberger, S.N.; Weiss, S.; Dommann, I.; Fenini, G.; Contassot, E.; Kramer, M.F.; Skinner, M.A.; Kundig, T.M.; et al. Microcrystalline Tyrosine and Aluminum as Adjuvants in Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy Protect from IgE-Mediated Reactivity in Mouse Models and Act Independently of Inflammasome and TLR Signaling. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 3151–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeldia, J.M.; Ferrer, M.; Davila, I.; Justicia, J.L. Adjuvants in Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy: Modulating and Enhancing the Immune Response. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 29, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, L.; Willers, J.; Hammann-Haenni, A.; Pfaar, O.; Stocker, H.; Mueller, P.; Renner, W.A.; Bachmann, M.F. Assessment of clinical efficacy of CYT003-QbG10 in patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: A phase IIb study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senti, G.; Crameri, R.; Kuster, D.; Johansen, P.; Martinez-Gomez, J.M.; Graf, N.; Steiner, M.; Hothorn, L.A.; Gronlund, H.; Tivig, C.; et al. Intralymphatic immunotherapy for cat allergy induces tolerance after only 3 injections. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senti, G.; Graf, N.; Haug, S.; Ruedi, N.; von Moos, S.; Sonderegger, T.; Johansen, P.; Kundig, T.M. Epicutaneous allergen administration as a novel method of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senti, G.; Johansen, P.; Haug, S.; Bull, C.; Gottschaller, C.; Muller, P.; Pfister, T.; Maurer, P.; Bachmann, M.F.; Graf, N.; et al. Use of A-type CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant in allergen-specific immunotherapy in humans: A phase I/IIa clinical trial. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senti, G.; von Moos, S.; Tay, F.; Graf, N.; Sonderegger, T.; Johansen, P.; Kundig, T.M. Epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy ameliorates grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled dose escalation study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basomba, A.; Tabar, A.I.; de Rojas, D.H.; Garcia, B.E.; Alamar, R.; Olaguibel, J.M.; del Prado, J.M.; Martin, S.; Rico, P. Allergen vaccination with a liposome-encapsulated extract of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 109, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.E.; Kline, J.N. Use of CpG oligonucleotides in treatment of asthma and allergic disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Couroux, P.; Hickey, P.; Salapatek, A.M.; Laidler, P.; Larche, M.; Hafner, R.P. Fel d 1-derived peptide antigen desensitization shows a persistent treatment effect 1 year after the start of dosing: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 103–109.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orengo, J.M.; Radin, A.R.; Kamat, V.; Badithe, A.; Ben, L.H.; Bennett, B.L.; Zhong, S.; Birchard, D.; Limnander, A.; Rafique, A.; et al. Treating cat allergy with monoclonal IgG antibodies that bind allergen and prevent IgE engagement. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyaraj, E.; Li, Q.; Sun, P.; Sherrill, S. Anti-Fel d1 immunoglobulin Y antibody-containing egg ingredient lowers allergen levels in cat saliva. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 1098612X19861218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyaraj, E.; Gardner, C.; Filipi, I.; Cramer, K.; Sherrill, S. Reduction of active Fel d1 from cats using an antiFel d1 egg IgY antibody. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2019, 7, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoms, F.; Jennings, G.T.; Maudrich, M.; Vogel, M.; Haas, S.; Zeltins, A.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Riond, B.; Grossmann, J.; Hunziker, P.; et al. Immunization of cats to induce neutralizing antibodies against Fel d 1, the major feline allergen in human subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeltins, A.; West, J.; Zabel, F.; El Turabi, A.; Balke, I.; Haas, S.; Maudrich, M.; Storni, F.; Engeroff, P.; Jennings, G.T.; et al. Incorporation of tetanus-epitope into virus-like particles achieves vaccine responses even in older recipients in models of psoriasis, Alzheimer’s and cat allergy. NPJ Vaccines 2017, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F.; Rohrer, U.H.; Kundig, T.M.; Burki, K.; Hengartner, H.; Zinkernagel, R.M. The influence of antigen organization on B cell responsiveness. Science 1993, 262, 1448–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F.; Jennings, G.T. Vaccine delivery: A matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawankar, R. Allergic diseases and asthma: A global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.K.; Leung, D.Y.M. Dog and Cat Allergies: Current State of Diagnostic Approaches and Challenges. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaar, O.; Demoly, P.; Gerth van Wijk, R.; Bonini, S.; Bousquet, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Durham, S.R.; Jacobsen, L.; Malling, H.J.; Mosges, R.; et al. Recommendations for the standardization of clinical outcomes used in allergen immunotherapy trials for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: An EAACI Position Paper. Allergy 2014, 69, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Guideline on the Clinical Development of Products for Specific Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Allergic Diseases; European Medecine Agency: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaar, O.; Alvaro, M.; Cardona, V.; Hamelmann, E.; Mosges, R.; Kleine-Tebbe, J. Clinical trials in allergen immunotherapy: Current concepts and future needs. Allergy 2018, 73, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchia, D.; Melioli, G.; Pravettoni, V.; Nucera, E.; Piantanida, M.; Caminati, M.; Campochiaro, C.; Yacoub, M.-R.; Schiavino, D.; Paganelli, R.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of diagnostic methods in adult food allergy. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2015, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant# | Age | Sex | Age When Allergy Was Observed the First Time | Affected Organs | Baseline VAS Score (0–10) Without Direct Interaction with Cat | Maximal VAS score (0 –10) After direct interaction with cat | Continued in Follow up Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes | Nose | Lungs/Bronchia | Palate | |||||||

| 1 | 50 | female | 10 | x | x | 2.5 | 8.8 | x | ||

| 2 | 29 | female | 8 | x | x | x | 3.5 | 9.2 | x | |

| 3 | 21 | male | 21 | x | x | x | 3.9 | 7.2 | x | |

| 4 | 43 | female | 28 | x | x | 1.1 | 7 | x | ||

| 5 | 24 | female | 22 | x | x | x | 3.7 | 7.2 | x | |

| 6 | 45 | male | 23 | x | x | 4.2 | 9 | - | ||

| 7 | 40 | female | 10 | x | x | 1.3 | 5.6 | x | ||

| 8 | 28 | female | 12 | x | x | 0.3 | 7.7 | x | ||

| 9 | 51 | female | 41 | x | x | x | 1.4 | 8.5 | - | |

| 10 | 37 | female | 23 | x | x | 1.9 | 4.9 | - | ||

| Mean/Aver. | 36.8 ±10.8 | 8 ♀; 2 ♂ | 19.0 ± 11.3 | 9/10 | 7/10 | 6/10 | 2/10 | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 7/10 |

| Adverse Event | Severity | Participant # | Total Number | Percentage of All AEs | Related to Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema and pruritus | mild | 9 | 3 | 17.6% | Possible |

| Tooth infection | moderate | 9 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Common cold | mild | 2, 4, 6, 8 | 6 | 35.2% | No |

| Nausea with vomiting | moderate | 10 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Nettle rash | moderate | 10 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Cat allergy reactions | mild | 24 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Swollen lips | mild | 10 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Gastroenteritis | moderate | 8 | 1 | 5.9% | No |

| Cat bite (hand) | severe | 2 | 1 | 5.9% | Possible |

| Chronic urticaria (strong pruritus and wheal formation) | moderate | 10 | 1 | 5.9% | Possible |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thoms, F.; Haas, S.; Erhart, A.; Nett, C.S.; Rüfenacht, S.; Graf, N.; Strods, A.; Patil, G.; Leenadevi, T.; Fontaine, M.C.; et al. Immunization of Cats against Fel d 1 Results in Reduced Allergic Symptoms of Owners. Viruses 2020, 12, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12030288

Thoms F, Haas S, Erhart A, Nett CS, Rüfenacht S, Graf N, Strods A, Patil G, Leenadevi T, Fontaine MC, et al. Immunization of Cats against Fel d 1 Results in Reduced Allergic Symptoms of Owners. Viruses. 2020; 12(3):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12030288

Chicago/Turabian StyleThoms, Franziska, Stefanie Haas, Aline Erhart, Claudia S. Nett, Silvia Rüfenacht, Nicole Graf, Arnis Strods, Gauravraj Patil, Thonur Leenadevi, Michael C. Fontaine, and et al. 2020. "Immunization of Cats against Fel d 1 Results in Reduced Allergic Symptoms of Owners" Viruses 12, no. 3: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12030288

APA StyleThoms, F., Haas, S., Erhart, A., Nett, C. S., Rüfenacht, S., Graf, N., Strods, A., Patil, G., Leenadevi, T., Fontaine, M. C., Toon, L. A., Jennings, G. T., Senti, G., Kündig, T. M., & Bachmann, M. F. (2020). Immunization of Cats against Fel d 1 Results in Reduced Allergic Symptoms of Owners. Viruses, 12(3), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12030288