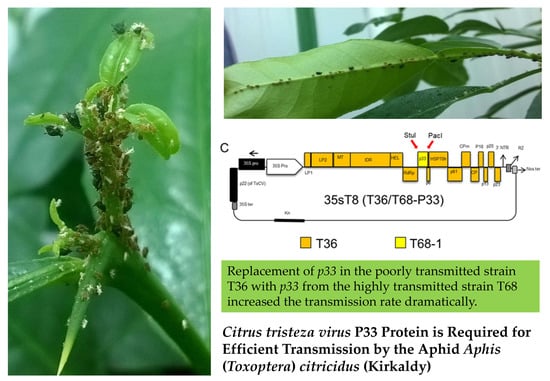

Citrus tristeza virus P33 Protein Is Required for Efficient Transmission by the Aphid Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus (Kirkaldy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Citrus Plants, CTV Isolates, and Aphid Colonies

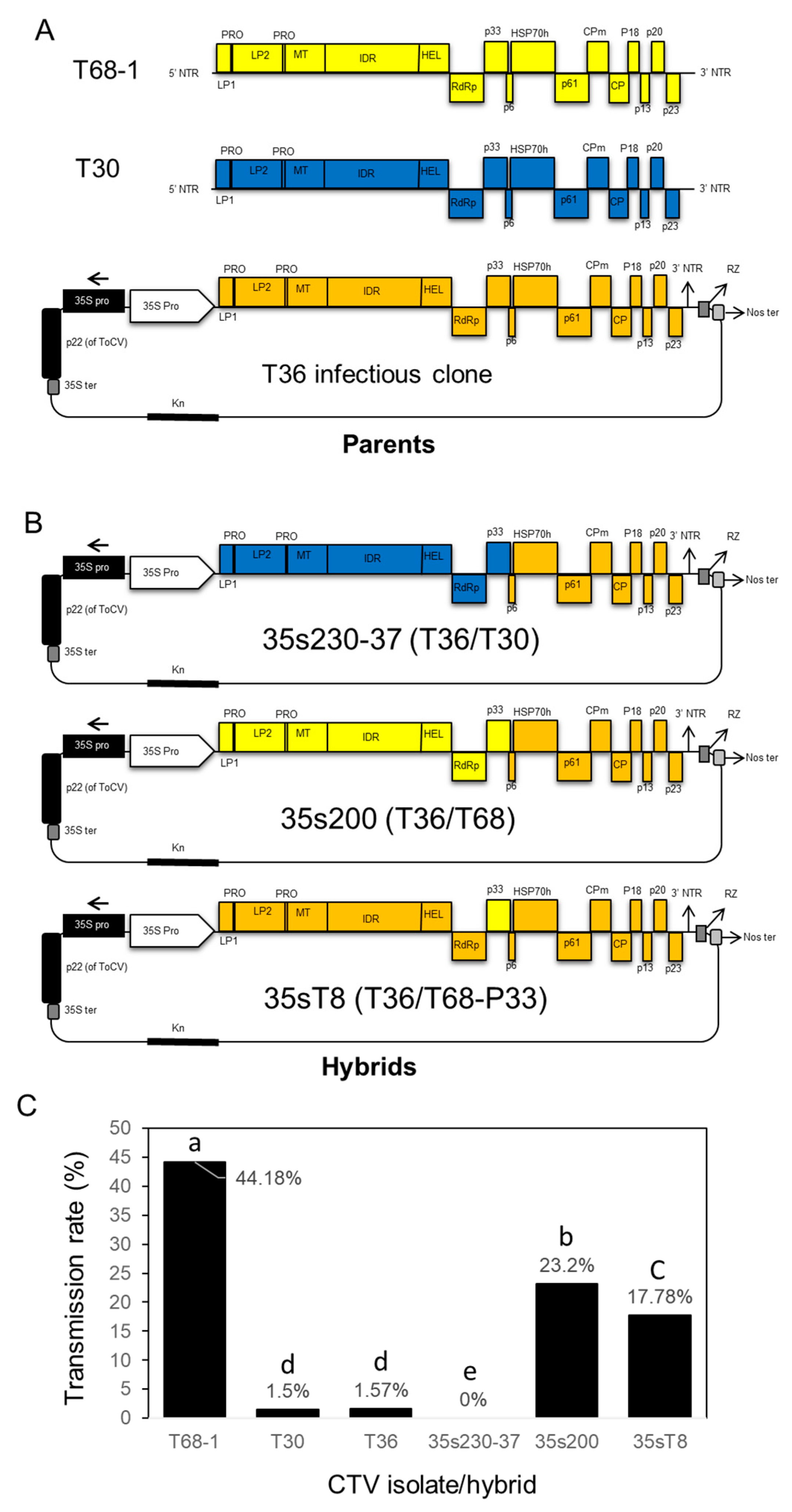

2.2. Construction of CTV Hybrids

2.3. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

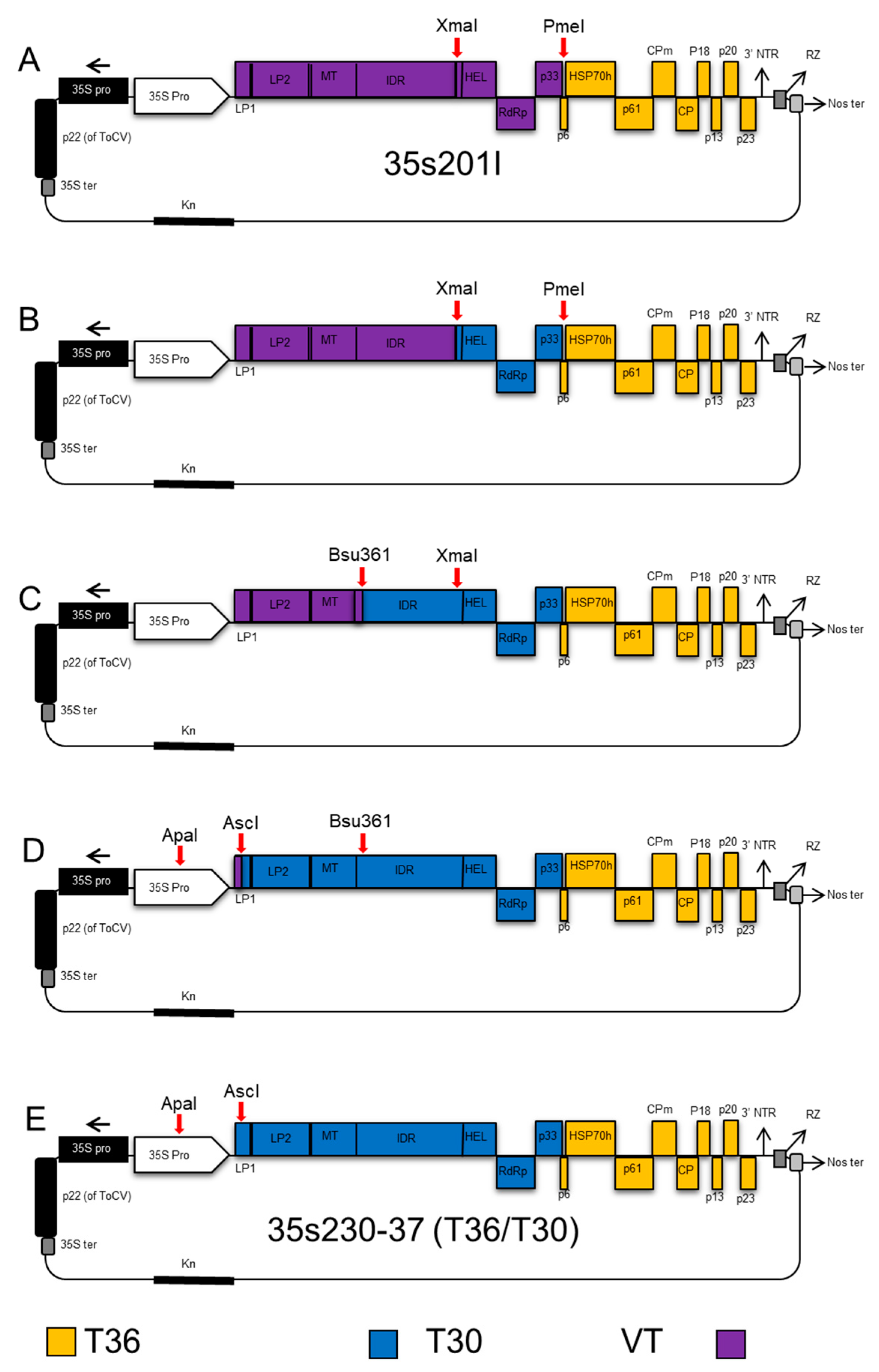

2.4. CTV T36/T30 Infectious Hybrid Clone (35s230-37)

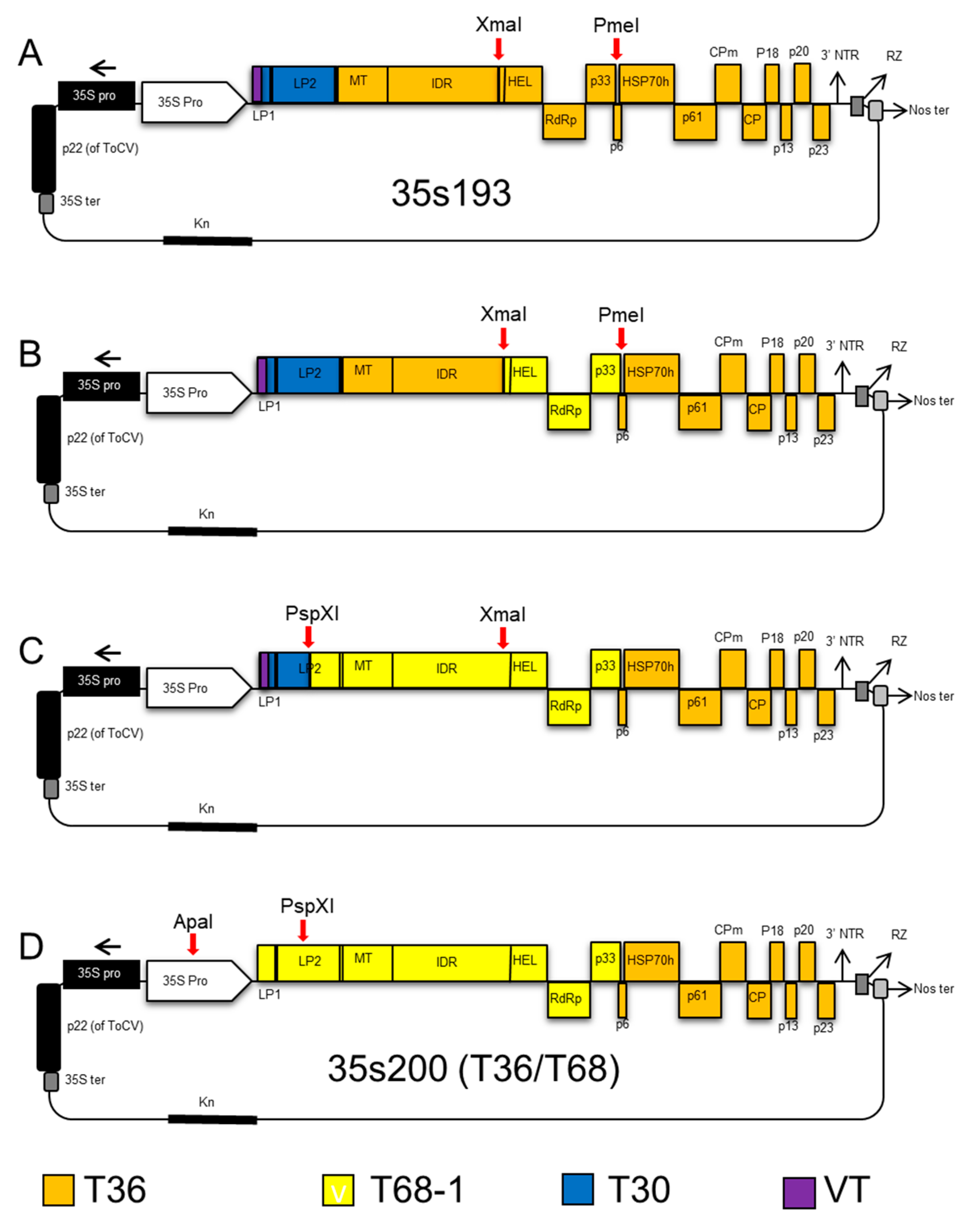

2.5. CTV T36/T68 Infectious Hybrid Clone (35s200)

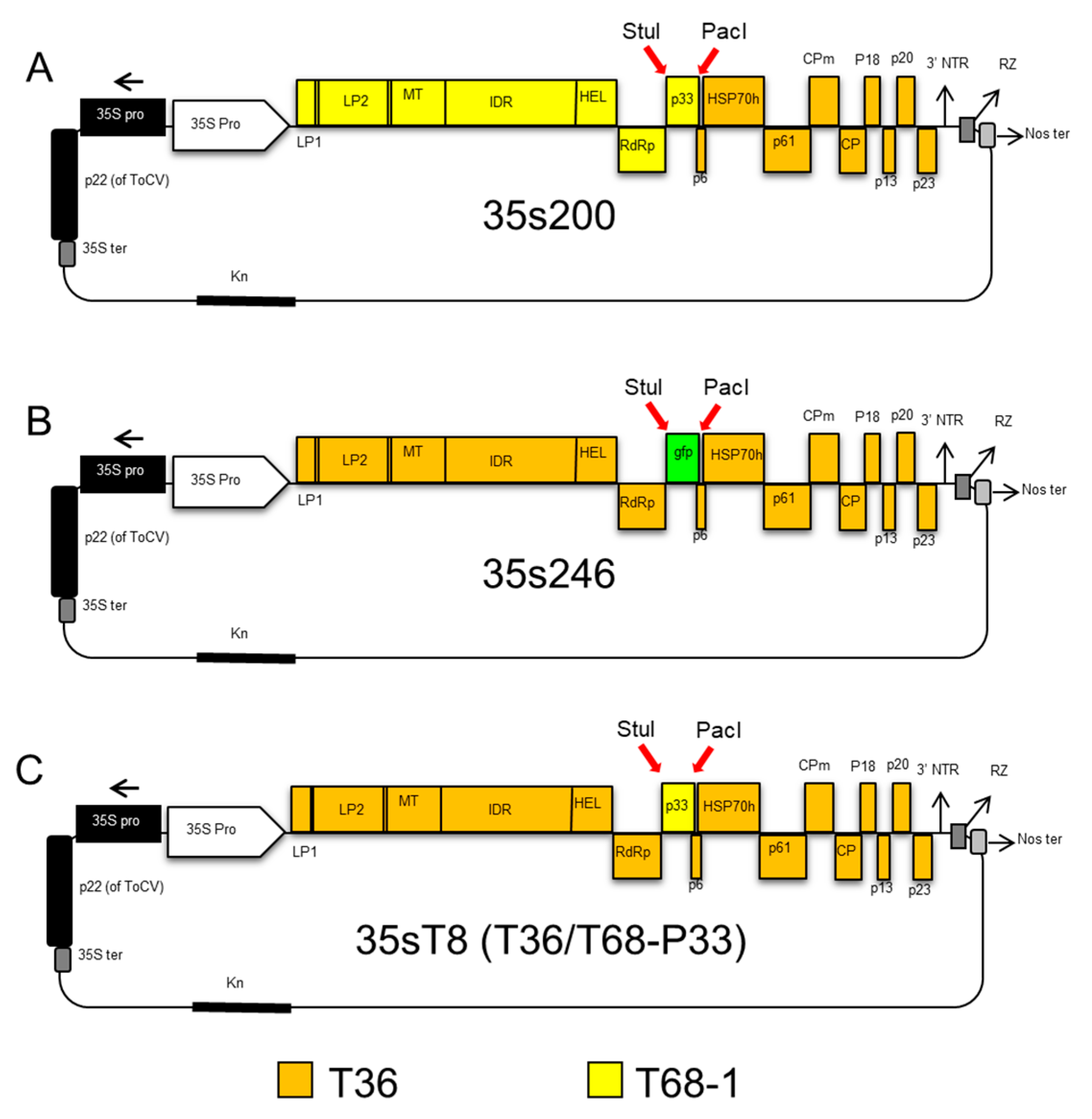

2.6. CTV T36 Containing P33 from the T68 Infectious Hybrid Clone (35sT8; T36/T68-P33)

2.7. Agrobacterium Infiltration of CTV Constructs into Nicotiana Benthamiana

2.8. CTV Virion Isolation and Bark Flap Inoculation into Citrus

2.9. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.10. Aphid Transmission Assays

3. Results

3.1. The Constructed Infectious Hybrid Clones Replicate Normally in C. macrophylla

3.2. Replacement of 5′-End Terminus Genes (lp1 to p33) of the Poorly Transmitted Isolate T36 with those from the Highly Transmissible Isolate T68-1 Significantly Increases the Transmission Rate by A. citricidus

3.3. Replacement of p33 from CTV-T36 with p33 from CTV-T68-1 Significantly Increased the Transmission Rate by A. citricidus

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hull, R. Comparative Plant Virology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki, E.P. A Top Ten List for Economically Important Plant Viruses. Arch. Virol. 2014, 160, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S.J.; Killiny, N.; Tatineni, S.; Gowda, S.; Cowell, S.J.; Shilts, T.; Dawson, W.O. Sequence Variation in Two Genes Determines the Efficacy of Transmission of Citrus Tristeza Virus by the Brown Citrus Aphid. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 3555–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rocha-Pena, M.A. Citrus Tristeza Virus and Its Aphid Vector Toxoptera Citmicida: Threats to Citrus Production in the Caribbean and Central and North America. Plant Dis. 1995, 79, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerni, S.; Ruščić, J.; Nolasco, G.; Gatin, Ž.; Krajačić, M.; Škorić, D. Stem Pitting and Seedling Yellows Symptoms of Citrus Tristeza Virus Infection May Be Determined by Minor Sequence Variants. Virus Genes 2007, 36, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.; Ambrós, S.; Albiach-Martí, M.R.; Guerri, J.; Peña, L. Citrus Tristeza Virus: A Pathogen That Changed the Course of the Citrus Industry. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomi, R.K.; Lastra, R.; Stoetzel, M.B.; Damsteegt, V.D.; Lee, R.F.; Garnsey, S.M.; Gottwald, T.R.; Niblett, C.L.; Rocha-Pena, M.A. Establishment of the Brown Citrus Aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Central America and the Caribbean Basin and Transmission of Citrus Tristeza Virus. J. Econ. Èntomol. 1994, 87, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Joseph, M.; Marcus, R.; Lee, R.F. The Continuous Challenge of Citrus Tristeza Virus Control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1989, 27, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Cowell, S.J.; Dawson, W.O. Bottlenecks and Complementation in the Aphid Transmission of Citrus Tristeza Virus Populations. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 3373–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.J. Citrus Tristeza Virus: Evolution of Complex and Varied Genotypic Groups. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawassi, M.; Mietkiewska, E.; Gofman, R.; Yang, G.; Bar-Joseph, M. Unusual Sequence Relationships Between Two Isolates of Citrus Tristeza Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1996, 77, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brlansky, R.H.; Damsteegt, V.D.; Howd, D.S.; Roy, A. Molecular Analyses of Citrus Tristeza Virus Subisolates Separated by Aphid Transmission. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S.J.; Dawson, T.E.; Pearson, M.N. Complete Genome Sequences of Two Distinct and Diverse Citrus Tristeza Virus Isolates from New Zealand. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.C.K.; Falk, B.W. Virus-Vector Interactions Mediating Nonpersistent and Semipersistent Transmission of Plant Viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, C.; Mirkov, T.; Da Graça, J.; Lee, R. Citrus Tristeza Virus Transmission by the Toxoptera Citricida Vector: In Vitro Acquisition and Transmission and Infectivity Immunoneutralization Experiments. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 134, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatineni, S.; Robertson, C.J.; Garnsey, S.M.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Gowda, S.; Dawson, W.O. Three Genes of Citrus Tristeza Virus Are Dispensable for Infection and Movement Throughout Some Varieties of Citrus Trees. Virology 2008, 376, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, T.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Mawassi, M.; Albiach-Martí, M.; Ayllón, M.; Gowda, S.; Hilf, M.; Moreno, P.; Garnsey, S.; Dawson, W. Amplification of Citrus Tristeza Virus from a cDNA Clone and Infection of Citrus Trees. Virology 2001, 280, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasev, A.V.; Boyko, V.; Gowda, S.; Nikolaeva, O.; Hilf, M.; Koonin, E.; Niblett, C.; Cline, K.; Gumpf, D.; Lee, R.; et al. Complete Sequence of the Citrus Tristeza Virus RNA Genome. Virology 1995, 208, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, T.; Gowda, S.; Mawassi, M.; Albiach-Marti, M.R.; Ayllón, M.A.; Robertson, C.; Garnsey, S.M.; Dawson, W.O. Closterovirus Encoded HSP70 Homolog and p61 in Addition to Both Coat Proteins Function in Efficient Virion Assembly. Virology 2000, 278, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolja, V.V.; Kreuze, J.F.; Valkonen, J.P.T. Comparative and Functional Genomics of Closteroviruses. Virus Res. 2006, 117, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Folimonov, A.; Shintaku, M.; Li, W.-X.; Falk, B.W.; Dawson, W.O.; Ding, S.-W. Three Distinct Suppressors of RNA Silencing Encoded by a 20-kb Viral RNA Genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15742–15747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; Robertson, C.J.; Garnsey, S.M.; Dawson, W.O. A Plant Virus Evolved by Acquiring Multiple Nonconserved Genes to Extend Its Host Range. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17366–17371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killiny, N.; Harper, S.J.; Alfaress, S.; El Mohtar, C.; Dawson, D.W. Minor Coat and Heat Shock Proteins Are Involved in the Binding of Citrus Tristeza Virus to the Foregut of Its Aphid Vector, Toxoptera Citricida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6294–6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, T.; Gowda, S.; Boyko, V.P.; Albiach-Marti, M.R.; Mawassi, M.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Karasev, A.V.; Dolja, V.; Hilf, M.E.; Lewandowski, D.J.; et al. An Engineered Closterovirus RNA Replicon and Analysis of Heterologous Terminal Sequences for Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7433–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyanarayana, T.; Gowda, S.; Ayllón, M.A.; Dawson, W.O. Frameshift Mutations in Infectious cDNA Clones of Citrus Tristeza Virus: A Strategy to Minimize the Toxicity of Viral Sequences to Escherichia coli. Virology 2003, 313, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiach-Martí, M.R.; Mawassi, M.; Gowda, S.; Satyanarayana, T.; Hilf, M.E.; Shanker, S.; Almira, E.C.; Vives, M.C.; López, C.; Guerri, J.; et al. Sequences of Citrus Tristeza VirusSeparated in Time and Space Are Essentially Identical. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6856–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, S.; Satyanarayana, T.; Robertson, C.J.; Garnsey, S.M.; Dawson, W.O. Infection of Citrus Plants with Virions Generated in Nicotiana Benthamiana Plants Agroinfiltrated with a Binary Vector Based Citrus Tristeza Virus. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the International Organization of Citrus Virologists, IOCV, Riverside, CA, USA, 2005; Hilf, M.E., Duran-Vila, N., Rocha-Peña, M.A., Eds.; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Cañizares, M.C.; Navas-Castillo, J.; Moriones, E. Multiple Suppressors of RNA Silencing Encoded by Both Genomic RNAs of the Crinivirus, Tomato Chlorosis Virus. Virology 2008, 379, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Reed, J.C.; Prokhnevsky, A.I.; Chapman, E.J.; Mawassi, M.; Koonin, E.V.; Carrington, J.C.; Dolja, V.V. Diverse Suppressors of RNA Silencing Enhance Agroinfection by a Viral Replicon. Virology 2006, 346, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasschau, K.D.; Xie, Z.; Allen, E.; Llave, C.; Chapman, E.J.; Krizan, K.A.; Carrington, J.C. P1/HC-Pro, a Viral Suppressor of RNA Silencing, Interferes with Arabidopsis Development and miRNA Function. Dev. Cell 2003, 4, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mohtar, C.; Dawson, W.O. Exploring the Limits of Vector Construction Based on Citrus Tristeza Virus. Virology 2014, 448, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrós, S.; El-Mohtar, C.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Peña, L.; Guerri, J.; Dawson, W.O.; Moreno, P. Agroinoculation of Citrus Tristeza Virus Causes Systemic Infection and Symptoms in the Presumed Nonhost Nicotiana Benthamiana. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsey, S.M.; Cambra, M. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Citrus Pathogens. In Graft-Transmissible Diseases. Citrus-Handbook for Detection and Diagnosis; Roistacher, C.N., Ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1991; pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Folimonova, S.Y.; Robertson, C.J.; Shilts, T.; Folimonov, A.S.; Hilf, M.E.; Garnsey, S.M.; Dawson, W.O. Infection with Strains of Citrus Tristeza Virus Does Not Exclude Superinfection by Other Strains of the Virus. J. Virol. 2009, 84, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, C.J.; Garnsey, S.M.; Satyanarayana, T.; Folimonova, S.; Dawson, W.O. Efficient Infection of Citrus Plants with Different Cloned Constructs of Citrus Tristeza Virus Amplified in Nicotiana Benthamiana Protoplasts. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the International Organization of Citrus Virologists. IOCV, Riverside, CA, USA, 2005; Hilf, M.E., Duran-Vila, N., Rocha-Peña, M.A., Eds.; pp. 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Uzest, M.; Gargani, D.; Dombrovsky, A.; Cazevieille, C.; Cot, D.; Blanc, S. The “Acrostyle”: A Newly Described Anatomical Structure in Aphid Stylets. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2010, 39, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Calvino, L.; Goytia, E.; López-Abella, D.; Giner, A.; Urizarna, M.; Vilaplana, L.; López-Moya, J.-J. The Helper-Component Protease Transmission Factor of Tobacco Etch Potyvirus Binds Specifically to an Aphid Ribosomal Protein Homologous to the Laminin Receptor Precursor. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 2862–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, A.; Folimonova, S.Y. The Conundrum of a Unique Protein Encoded by Citrus Tristeza Virus That Is Dispensable for Infection of Most Hosts Yet Shows Characteristics of a Viral Movement Protein. Virology 2015, 485, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Folimonova, S.Y. The p33 Protein of Citrus Tristeza Virus Affects Viral Pathogenicity by Modulating a Host Immune Response. New Phytol. 2018, 221, 2039–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, T.N.M.; Kang, S.H.; Bak, A.; Folimonova, S.Y. A Non-Conserved p33 Protein of Citrus Tristeza Virus Interacts with Multiple Viral Partners. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer | Orientation | Restriction Enzyme | Sequence 5′—3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1882 | Reverse | CCCGCACTTGCGGGGAGAAACCGTACG | |

| C2267 | Forward | * ApaI | GTTGGGCCCGATCTCCTTTGCCCCAGAGATCACAATGGACGACTT |

| C2268 | Forward | - | AATTTCGATTCAAATTCACCCGTATCTCCGGAGCTCGAT |

| C2275 | Forward | - | CTGAACGTGGGAAGATTGGGGATTTCAGTTTTCCGAGT |

| C2276 | Reverse | - | ACTCGGAAAACTGAAATCCCCAATCTTCCCACGTTCAG |

| C2277 | Forward | - | TCCTAGTCATCACTCGAGTGCCGCTCGTGGGCAACGTT |

| C2278 | Forward | - | TCAGTTTTTCGCGATTTTTGTACGATTCGCGTTA |

| C2279 | Forward | - | CCCGTCGCACGTGACATAACGTACAAGAAGATGACCAA |

| C2280 | Reverse | - | AGACTATGCTCCGAATTAGTGAACGTCAAATCTTT |

| C2281 | Reverse | - | ATAGCCACCGTCGAAAACGTGGTACCAAAGTCTA |

| C2296 | Forward | - | AAGGTATAATTCGAGGAAGTCCTTCTATACGCG T |

| C2298 | Reverse | - | ACTCGGAGGGCCAGCCGAACGACGACTAACACCG |

| C2299 | Forward | - | GTT GAA GGC TGT GGG TTT CGA CAG GAA GTT AAC C |

| C2300 | Reverse | - | ACAGGATACTTTAGTACAGTAGTCGGAAAAGTACTTC |

| C2302 | Reverse | - | ACCAAAGTCTAGACCCAGAAGCACCATACCGCT |

| C2331 | Reverse | Bsu36I | AGTTCCTGAGGTACGATTTCACGTATCTCTCTACG |

| C2332 | Forward | Bsu36I | GTACCTCAGGAACTCGTTTAATATAAGTTTCGC |

| C2348 | Forward | - | TGAATGCTAAGACTTTTGAATGGACTTGGAA |

| C2352 | Forward | - | ACGTAGGTGGTTGCCCATTATTTCATTTACGTAAGTTTCTGCTTCTACCTTTGA |

| C2353 | Reverse | - | TCAAAGGTAGAAGCAGAAACTTACGTAAATGAAATAATGGGCAACCACCTACGT |

| C2354 | Forward | - | ATATATGACCAAAATTTGTTGATGTGCAGGTGCGGGTCATACAGGAGTTCACGTTTGCA |

| C2355 | Reverse | - | TGCAAACGTGAACTCCTGTATGACCCGCACCTGCACATCAACAAATTTTGGTCATATAT |

| C2356 | Forward | Bsu36I | CATACCTCAGGAACTCGTTTAATATGAGTTTCGTAGACT |

| C2357 | Reverse | Bsu36I | GTTCCTGAGGTATGATCTCACGCACCTCTCCACA |

| C-2358 C2459 | Reverse Forward | XmaI XmaI | GGACCCGGGCAAAG CACCAAACCGTCGTCGCAAAACATGAACT TTGCGACGACGGTTTGGTGCTTTGCCCGGGTCCGAAAAAACGCGATTCGCT |

| C2470 | Reverse | PacI | ACCTTAATTAATCATATAAATATGATGGCTATCAAACCGCTCATT |

| C2475 | Forward | StuI | AATAGGCCTTGTTTGCCTTCGCGAGTGAAAACCAAGATATTAGAAG |

| Isolates/Hybrids | O.D. @ 405 nm * |

|---|---|

| Control | 0.25 ± 0.10 a |

| T36 | 3.41 ± 0.05 b |

| WT-T68 | 3.50 ± 0.04 b |

| WT-T30 | 3.02 ± 0.20 b |

| 35s230-37 (CTV T36/T30) | 3.19 ± 0.20 b |

| 35s200 (CTV T36/T68) | 3.40 ± 0.10 b |

| 35sT8 (CTV T36/T68-P33) | 3.36 ± 0.02 b |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shilts, T.; El-Mohtar, C.; Dawson, W.O.; Killiny, N. Citrus tristeza virus P33 Protein Is Required for Efficient Transmission by the Aphid Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus (Kirkaldy). Viruses 2020, 12, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12101131

Shilts T, El-Mohtar C, Dawson WO, Killiny N. Citrus tristeza virus P33 Protein Is Required for Efficient Transmission by the Aphid Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus (Kirkaldy). Viruses. 2020; 12(10):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12101131

Chicago/Turabian StyleShilts, Turksen, Choaa El-Mohtar, William O. Dawson, and Nabil Killiny. 2020. "Citrus tristeza virus P33 Protein Is Required for Efficient Transmission by the Aphid Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus (Kirkaldy)" Viruses 12, no. 10: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12101131

APA StyleShilts, T., El-Mohtar, C., Dawson, W. O., & Killiny, N. (2020). Citrus tristeza virus P33 Protein Is Required for Efficient Transmission by the Aphid Aphis (Toxoptera) citricidus (Kirkaldy). Viruses, 12(10), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12101131