Detection of a Novel Phlebovirus (Drin Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania

Abstract

1. Introduction

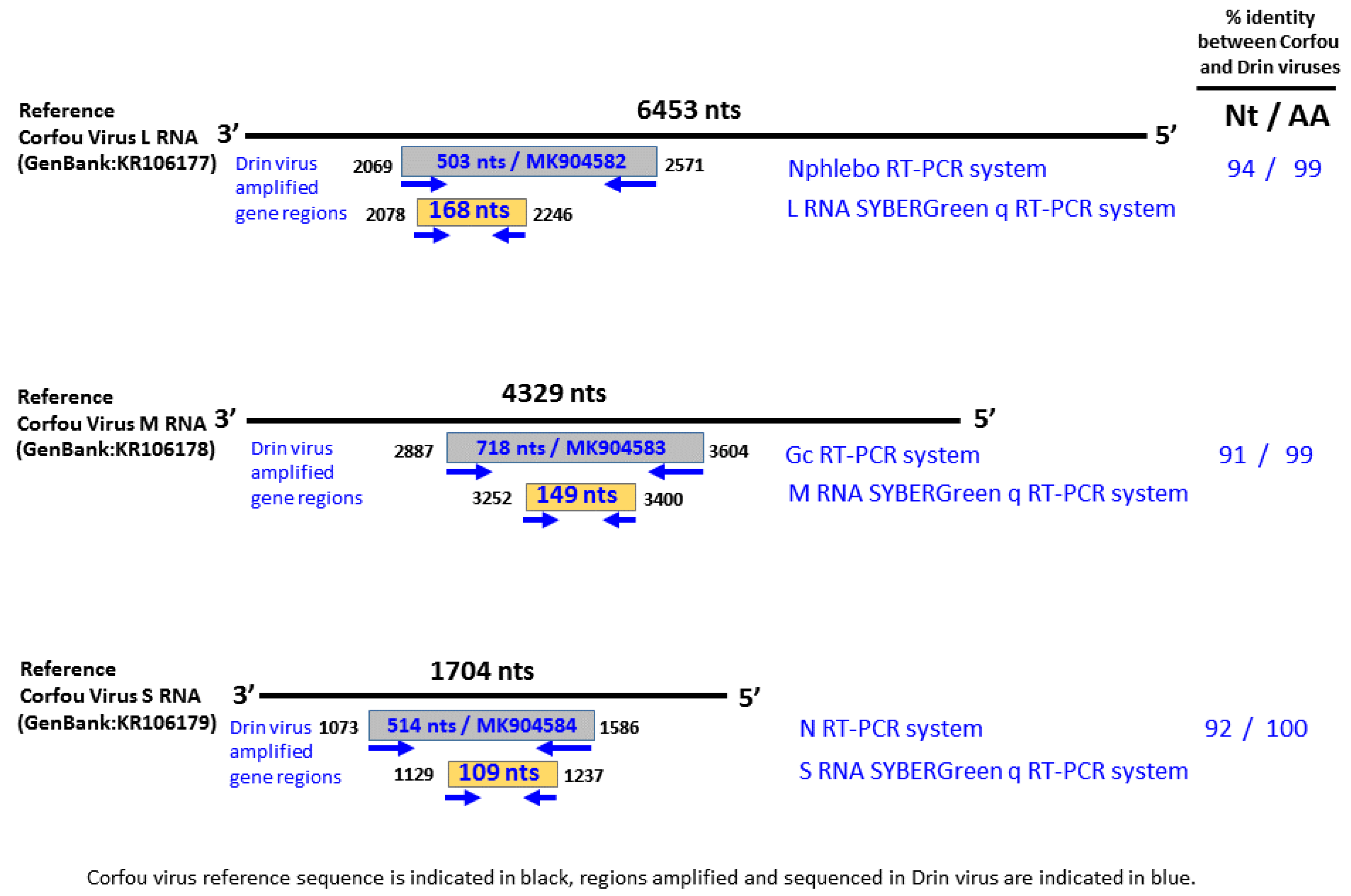

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sand Fly Trapping

2.2. Sand Fly Homogenization, Tentative Isolation in Ncell Lines and Baby Mice

2.3. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Molecular Assays

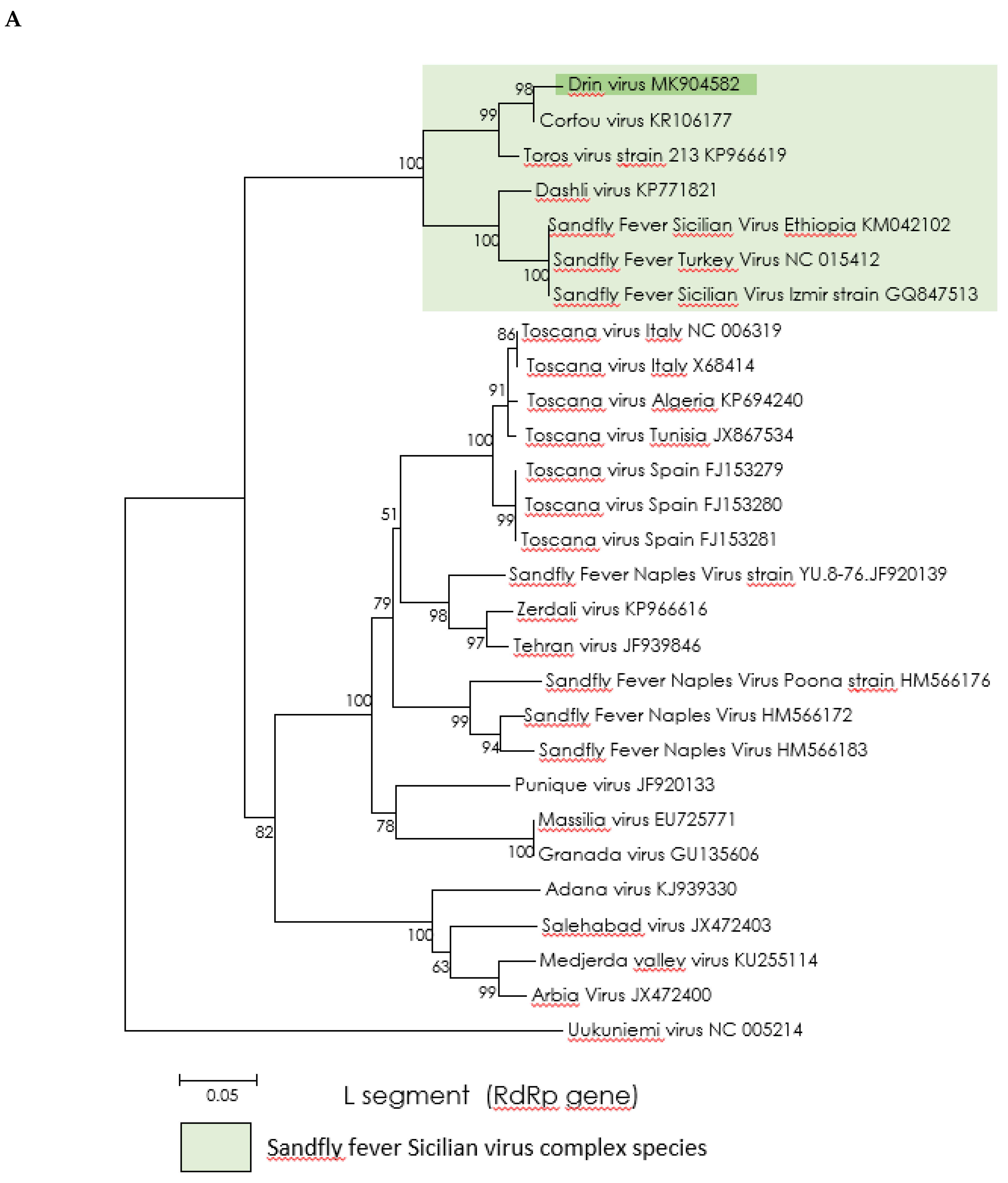

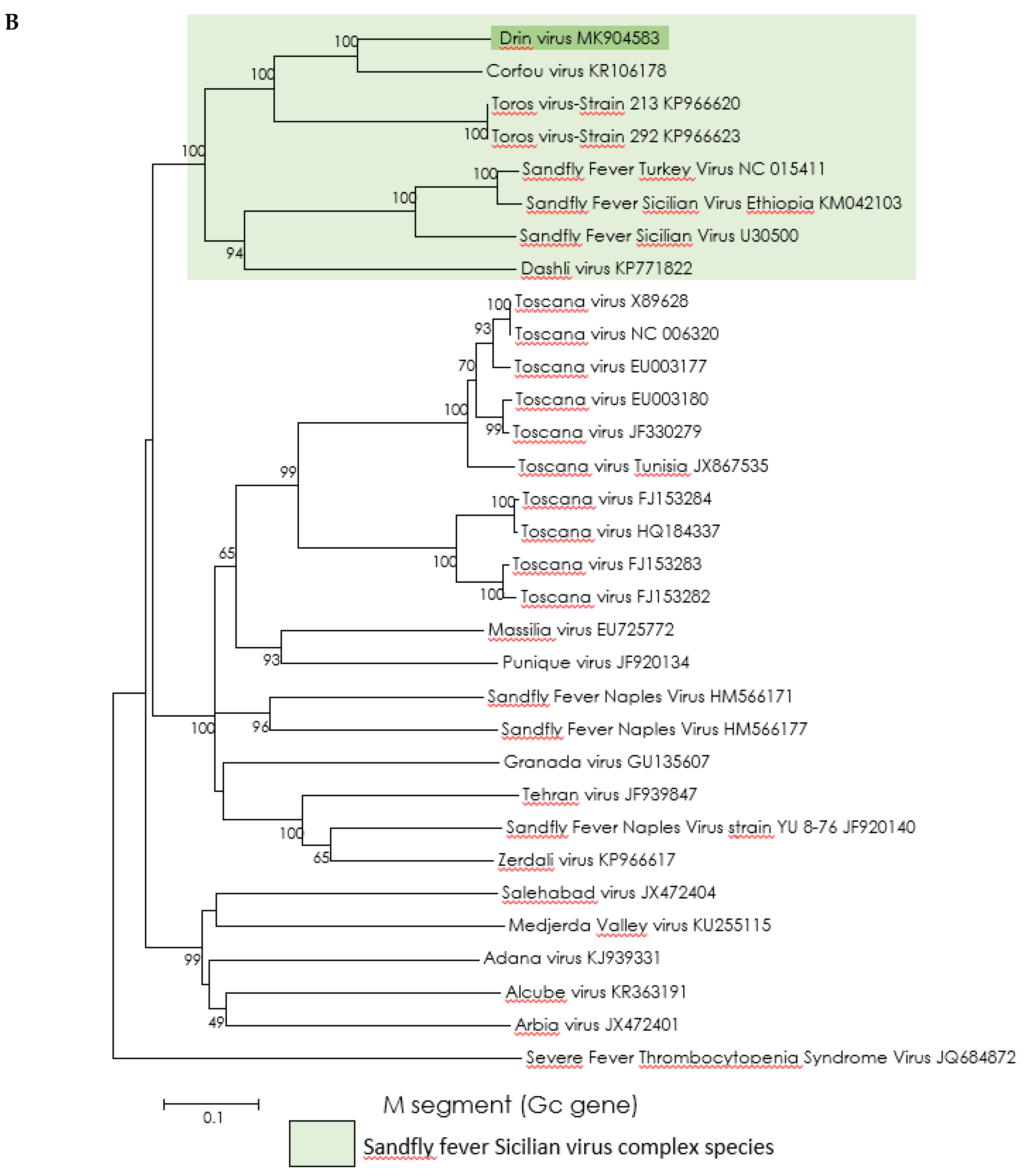

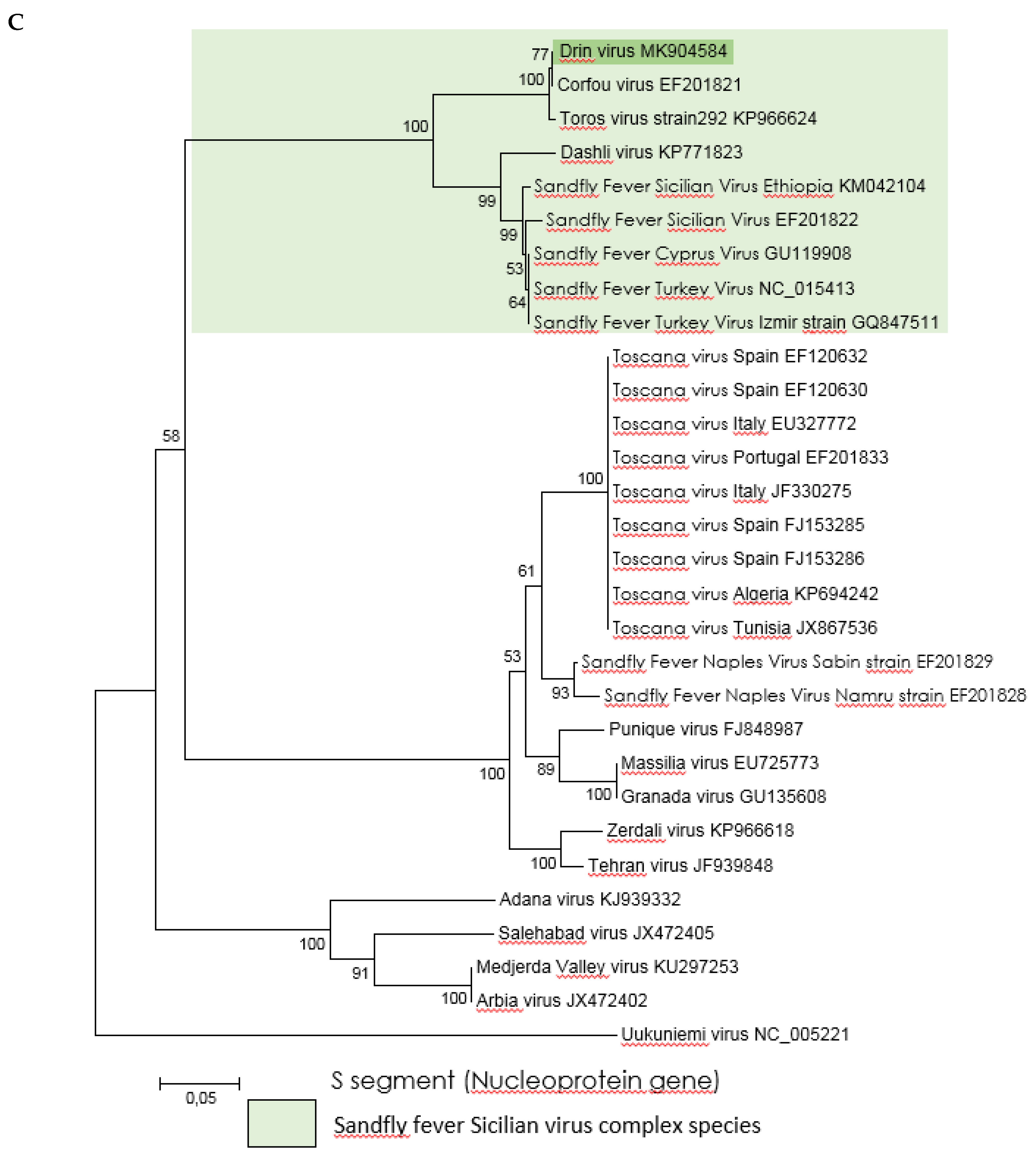

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Genotyping the Sand Flies of Virus-Positive Pool

3. Results

3.1. Sand Fly Collection and Virus Testing

3.2. Attempts of Virus Isolation

3.3. Genetic Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Drin Virus

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodhain, F.; Madulo-Leblond, G.; Hannoun, C.; Tesh, R.B. Le virus Corfou. Un nouveau Phlebovirus virus isole de Phlebotomes en Grece. Ann. De L’institut Pasteur/Virol. 1985, 136, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, A.B. Experimental studies on Phlebotomus (pappataci, sandfly) fever during World War II. Arch. Gesamte Virusforsch 1951, 4, 367–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, C.; Moin, V.V.; Ayhan, N.; Badakhshan, M.; Bichaud, L.; Rahbarian, N.; Javadian, E.A.; Alten, B.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. Isolation and sequencing of Dashli virus, a novel Sicilian-like virus in sandflies from Iran; genetic and phylogenetic evidence for the creation of one novel species within the Phlebovirus genus in the Bunyaviridae family. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.M.; Brennan, B. Emerging phleboviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 5, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killick-Kendrick, R. The biology and control of Phlebotomine sand flies. Clin. Dermatol. 1999, 17, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, D.; Esperti, F.; Vivarelli, A.; Valassina, M. Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory aspects of sandfly fever. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003, 16, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrel, R.N.; Gallian, P.; Navarro-Marí, J.M.; Nicoletti, L.; Papa, A.; Sánchez-Seco, M.P.; Tenorio, A.; de Lamballerie, X. Emergence of Toscana virus in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwassouf, S.; Maia, C.; Ayhan, N.; Coimbra, M.; Cristovao, J.M.; Richet, H.; Bichaud, L.; Campino, L.; Charrel, R.N. Neutralization-based seroprevalence of toscana virus and sandfly fever sicilian virus in dogs and cats from Portugal. J. Gen. Virol 2016, 97, 2816–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Velo, E.; Bino, S. A novel phlebovirus in Albanian sandflies. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Eur. Soc. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostou, V.; Pardalos, G.; Athanasiou-Metaxa, M.; Papa, A. Novel phlebovirus in febrile child, Greece. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velo, E.; Paparisto, A.; Bongiorno, G.; Di Muccio, T.; Khoury, C.; Bino, S.; Gramiccia, M.; Gradoni, L.; Maroli, M. Entomological and parasitological study on phlebotomine sandflies in central and northern Albania. Parasite 2005, 12, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velo, E.; Bongiorno, G.; Kadriaj, P.; Myrseli, T.; Crilly, J.; Lika, A.; Mersini, K.; Di Muccio, T.; Bino, S.; Gramiccia, M.; et al. The current status of phlebotomine sand flies in Albania and incrimination of Phlebotomus neglectus (Diptera, Psychodidae) as the main vector of Leishmania infantum. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, N.; Velo, E.; de Lamballerie, X.; Kota, M.; Kadriaj, P.; Ozbel, Y.; Charrel, R.N.; Bino, S. Detection of Leishmania infantum and a Novel Phlebovirus (Balkan Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, N.; Baklouti, A.; Prudhomme, J.; Walder, G.; Amaro, F.; Alten, B.; Moutailler, S.; Ergunay, K.; Charrel, R.N.; Huemer, H. Practical Guidelines for Studies on Sandfly-Borne Phleboviruses: Part I: Important Points to Consider Ante Field Work. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, H.; Prudhomme, J.; Amaro, F.; Baklouti, A.; Walder, G.; Alten, B.; Moutailler, S.; Ergunay, K.; Charrel, R.N.; Ayhan, N. Practical Guidelines for Studies on Sandfly-Borne Phleboviruses: Part II: Important Points to Consider for Fieldwork and Subsequent Virological Screening. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Seco, M.P.; Echevarría, J.M.; Hernández, L.; Estévez, D.; Navarro-Marí, J.M.; Tenorio, A. Detection and identification of Toscana and other phleboviruses by RT-nested-PCR assays with degenerated primers. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 71, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, A.J.; Lanciotti, R.S. Consensus amplification and novel multiplex sequencing method for S segment species identification of 47 viruses of the Orthobunyavirus, Phlebovirus, and Nairovirus genera of the family Bunyaviridae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 2398–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, M.; Sanchez-Seco, M.P.; Sall, A.A.; Ly, P.O.; Thiongane, Y.; Lô, M.M.; Schley, H.; Hufert, F.T. Rapid detection of important human pathogenic Phleboviruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, C.; Alwassouf, S.; Piorkowski, G.; Bichaud, L.; Tezcan, S.; Dincer, E.; Ergunay, K.; Ozbel, Y.; Alten, B.; de Lamballerie, X.; et al. Isolation, Genetic Characterization, and Seroprevalence of Adana Virus, a Novel Phlebovirus Belonging to the Salehabad Virus Complex, in Turkey. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4080–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esseghir, S.; Ready, P.D.; Ben-Ismail, R. Speciation of Phlebotomus sandflies of the subgenus Larroussius coincided with the late Miocene–Pliocene aridification of the Mediterranean subregion. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2000, 70, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çarhan, A.; Uyar, Y.; Özkaya, E.; Ertek, M.; Dobler, G.; Dilcher, M.; Wang, Y.; Spiegel, M.; Hufert, F.; Weidmann, M. Characterization of a sandfly fever Sicilian virus isolated during a sandfly fever epidemic in Turkey. J. Clin. Virol. 2010, 48, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.; Tempera, G.; Guglielmino, S. Incidence of arbovirus antibodies in bovine, ovine and human sera collected in Eastern Sicily. Acta. Virol. 1976, 20, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eitrem, R.; Stylianou, M.; Niklasson, B. High prevalence rates of antibody to three sandfly fever viruses (Sicilian, Naples and Toscana) among Cypriots. Epidemiol. Infect.. 1991, 107, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woyessa, A.B.; Omballa, V.; Wang, D.; Lambert, A.; Waiboci, L.; Ayele, W.; Ahmed, A.; Abera, N.A.; Cao, S.; Ochieng, M.; et al. An outbreak of acute febrile illness caused by Sandfly Fever Sicilian Virus in the Afar region of Ethiopia, 2011. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 91, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, N.; Charrel, R.N. Of phlebotomines (sandflies) and viruses: a comprehensive perspective on a complex situation. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2017, 22, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrefitte, C.N.; Grandadam, M.; Bessaud, M.; Andry, P.E.; Fouque, F.; Caro, V.; Diancourt, L.; Schuffenecker, I.; Pagès, F.; Tolou, H.; et al. Diversity of Phlebotomus perniciosus in Provence, southeastern France: Detection of two putative new phlebovirus sequences. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remoli, M.E.; Fortuna, C.; Marchi, A.; Bucci, P.; Argentini, C.; Bongiorno, G.; Maroli, M.; Gradoni, L.; Gramiccia, M.; Ciufolini, M.G. Viral isolates of a novel putative phlebovirus in the Marche Region of Italy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhioua, E.; Moureau, G.; Chelbi, I.; Ninove, L.; Bichaud, L.; Derbali, M.; Champs, M.; Cherni, S.; Salez, N.; Cook, S.; et al. Punique virus, a novel phlebovirus, related to sandfly fever Naples virus, isolated from sandflies collected in Tunisia. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesh, R.B. The genus Phlebovirus and its vectors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1988, 33, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, C.; Erisoz, K.O.; Alten, B.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. Sandfly-Borne Phlebovirus Isolations from Turkey: New Insight into the Sandfly fever Sicilian and Sandfly fever Naples Species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, N.; Alten, B.; Ivovic, V.; Martinkovic, F.; Kasap, O.E.; Ozbel, Y.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. Cocirculation of two Lineages of toscana Virus in Croatia. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichaud, L.; Piarroux, R.P.; Izri, A.; Ninove, L.; Mary, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. Low seroprevalence of sandfly fever Sicilian virus antibodies in humans, Marseille, France. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 1189–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddle, M.S.; Althoff, J.M.; Earhart, K.; Monteville, M.R.; Yingst, S.L.; Mohareb, E.W.; Putnam, S.D.; Sanders, J.W. Serological evidence of arboviral infection and self-reported febrile illness among US troops deployed to Al Asad, Iraq. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008, 136, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | Assay | Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L segment (RdRp gene) | real-time RT-qPCR | L-Corfou-Albania—Forward | AGCCACATAAGATGTGCAAG | 168 |

| L-Corfou-Albania—Reverse | CCTGTGAAGGGATTGAACAT | |||

| M segment (Gc gene) | RT-PCR | Gc—Forward | GAAGGACAACTGCTTAGCATG | 718 |

| Gc—Reverse | CATTACAGGAATAACAGCCTG | |||

| Nested PCR | Gc-Nested—Forward | ATGCGGATGCTTCAATGTT | 428 | |

| Gc-Nested—Reverse | CATTCTATGATGTCAGTCAT | |||

| real-time RT-qPCR | Gc-RealTime—Forward | TTAGGTCTTCATCTGGAGC | 149 | |

| Gc-RealTime—Reverse | CATTCTATGATGTCAGTCAT | |||

| S segment (N gene) | RT-PCR | N—Forward | TAGATGAGACCGTGGTCCA | 514 |

| N—Reverse | GTTGATGGCGGCAGACAT | |||

| Nested PCR | N-Nested—Forward | ATGCCAAGAAGATGATTATTC | 352 | |

| N-Nested—Reverse | GTGAGCATCAACAATGGCAT | |||

| real-time RT-qPCR | N-RealTime—Forward | ATGGATAGAATCAGTGGTCAG | 109 | |

| N-RealTime—Reverse | GCTCCTCTGAGTCCAACAT |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bino, S.; Velo, E.; Kadriaj, P.; Kota, M.; Moureau, G.; Lamballerie, X.d.; Bagramian, A.; Charrel, R.N.; Ayhan, N. Detection of a Novel Phlebovirus (Drin Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania. Viruses 2019, 11, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050469

Bino S, Velo E, Kadriaj P, Kota M, Moureau G, Lamballerie Xd, Bagramian A, Charrel RN, Ayhan N. Detection of a Novel Phlebovirus (Drin Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania. Viruses. 2019; 11(5):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050469

Chicago/Turabian StyleBino, Silvia, Enkelejda Velo, Përparim Kadriaj, Majlinda Kota, Gregory Moureau, Xavier de Lamballerie, Ani Bagramian, Remi N. Charrel, and Nazli Ayhan. 2019. "Detection of a Novel Phlebovirus (Drin Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania" Viruses 11, no. 5: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050469

APA StyleBino, S., Velo, E., Kadriaj, P., Kota, M., Moureau, G., Lamballerie, X. d., Bagramian, A., Charrel, R. N., & Ayhan, N. (2019). Detection of a Novel Phlebovirus (Drin Virus) from Sand Flies in Albania. Viruses, 11(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050469