Abstract

Symbiosis with ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi can be important for regeneration success. In a context of increasing regeneration failures in the coastal forest of maritime pine in Southwest France, we tried to identity whether differences in ECM communities could partly explain the variation of regeneration success and how they are influenced by forest practices and stand characteristics. In particular, we focused on the effects of harvesting methods (comparing mature forest with seed-tree regeneration and clear-cuts) and topography (bottom-, mid-, and top positions). Five field trials (two in regeneration failure areas and three in successful areas) were used to sample 450 one-year-old seedlings. Assessments of ECM of seedling nutrient concentrations and of seedling growth based on exploration types were made. ECM root colonisation was similar in all harvesting treatments, suggesting that enough inoculum remained alive after logging. Harvesting-induced effects modifying soil properties and light availability respectively impacted ECM composition and seedling growth. Topography-induced variations in water and nutrient availability led to changes in ECM composition, but had little impact on seedling growth. Contact, short-distance, and long-distance exploration types improved the nutritional status of seedlings (Ca, K, and N), showing that mycorrhization could play an important role in seedling vitality. However, neither ECM root colonisation nor exploration types could be related to regeneration failures.

1. Introduction

Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aït in Soland) is the dominant forestry tree species in south-western France, covering almost one million ha [1]. Most of the forest range in the interior land plains is renewed by planting, whereas natural regeneration is used in the coastal area, which represents 10% of this forest [1]. In addition to wood production, these coastal forests have a multifunctional role, including soil erosion protection, preservation of biodiversity, and tourism/public usage [2]. To accommodate these multiple objectives, the use of natural regeneration to renew forest stands limits soil disturbance (no soil ploughing, such as before plantations) and improves the conservation of genetic diversity and the capacity of forests to adapt to global change. However, in recent years, regeneration failures have increased in some areas, leading to significant economic losses [2,3]. The regeneration status is estimated by counting the number of seedlings two to three years after clearcutting: regeneration is considered successful if the number of seedlings per hectare is higher than 3000; failed if there are less than 1500 seedlings/ha; and semi-successful (i.e., it could be sufficient, but the stand should remain under surveillance) if the number of seedlings is between these two thresholds [2].

The period between germination and seedling establishment is often a crucial step in the process of natural regeneration [4,5], and is well-known to depend on soil, climate, and biotic factors [6,7,8]. This is particularly the case for forests that have soil seed banks with a short life lifespan (such as maritime pine) where regeneration occurs from the soil seed bank after clear-cutting. In areas where regeneration failures are observed, “security sowing” is generally applied to ensure regeneration [2]. One of the most important biotic factors involved in natural regeneration, but which is often overlooked, is the association between plants and ectomycorrhizae (ECM) fungi [9,10,11]. Throughout their extramatrical mycelial network, ECM fungi can represent up to 75% of the absorptive area and over 99% of the absorptive length [12]. This symbiotic relationship, obligatory for almost all conifer species, provides water and nutrients to the seedling in exchange for carbohydrates, thus improving seedling growth, nutrient concentrations, and the success of seedling recruitment [13,14]. It also improves seedling resistance against drought, pathogens, and heavy metals [15,16,17]. Considering the importance of ECM for plant nutrition and water acquisition in oligotrophic and dry systems [17,18,19], like the sandy-soil system of the coastal dune forest, this particular biotic interaction could be involved in the differences of natural regeneration observed in the region.

Hence, this study examined the ectomycorrhizal composition of pine seedlings one year after logging by using five field trials with contrasting natural regeneration success which are located throughout this region. It corresponds to an initial examination of the subject to determine whether this biotic interaction should be studied in more depth. ECM fungi were classified according to the typology of Agerer [20], which classified ECM into different exploration types (i.e., their ability to explore the soil) based on the extent of mycelium and the presence and differentiation of rhizomorphs. Shorter exploration types represent a lower carbon cost to the plant and are more prevalent in wet and/or nutrient-rich areas, whereas longer exploration types (i.e., fungi with rhizomorphs) are more prevalent in dry and/or nutrient-poor areas where seedlings need to increase their absorptive area [21,22,23].

ECM communities can be influenced by a large number of factors including soil properties such as pH, soil temperature, nutrient availability, soil moisture, and climatic factors [24,25,26]. Soil moisture is an important driver of fungal composition. In dry soils, a decrease of ECM colonisation can occur [27], as well as a shift in ECM species, leading to the appearance of ECM which are well-adapted to dry soils and less expensive in carbon for the host plant or which develop highly differentiated rhizomorphs [22,28]. Studies at regional scales have shown that ECM fungal composition could vary with precipitation and temperature [25,29,30].

ECM communities are also highly sensitive to forestry practices in relation to tree harvesting, which can strongly affect the development of new seedlings during the next forest rotation. Briefly, tree harvesting practices could: (i) represent a potential disturbance of topsoil layers where ECM fungi are abundant [31]; (ii) improve the colonisation of seedling roots by ECM fungi in the case of seed-tree cuts relative to clear-cut systems; and (iii) modify the overall aforementioned soil properties. More precisely, the effects of clear-cutting, reviewed by Jones et al. [32], are closely associated with the level of soil disturbance. When the forest floor is little disturbed during harvesting, clear cutting results in a decrease in ECM species richness and a change in species composition rather than a reduction in root colonization. Mycorrhizal inoculum can remain active in the soil for one to two years after harvesting [9] and does not appear to be limiting for seedling colonisation [32]. When soil is heavily disturbed (forest floor removal and/or soil compaction), harvesting also impacts ECM colonisation, reducing the available inoculum by breaking mycelial networks and modifying soil properties [11,33,34,35]. Secondly, the preservation of seed-trees in the stand after harvest, either by leaving individual trees [36] or by leaving patches of trees [37], can improve the fungal root colonization of seedlings and could enhance natural regeneration, especially under drought conditions [38,39]. Indeed, the pre-existing mycelial network established by the roots of surrounding adult trees permits the seedlings to connect to this network at a low carbon cost and this can improve seedling regeneration [14,40,41]. Partial cutting can promote the maintenance of active root tips, and seed-tree cuts can maintain an intermediate level of ECM colonisation between clear-cuts and forests [36,42]. Thirdly, the impacts of clear-cuts or seed-tree cuts on ECM communities are also due to the associated modifications of soil properties relative to hydric conditions, soil temperature, or nutrient availability [32].

In the face of observed regeneration failure, the more specific context of coastal dune forests was considered and regeneration practice other than standard clearcutting is currently being tested by preserving seed-trees in the stand. In addition, the topography induced by the dune ecosystem is a major characteristic of these coastal forests, and strongly impacts the distance to the water table which varies from 1–3 m at the bottom to 17 m at the top of the dunes [43]. Consequently, harvest practices (clear-cuts and seed-tree cuts vs mature stands) and topographical positions (bottom-, mid-, and top positions) were tested in this experiment as factors potentially affecting ECM communities and their relationship with seedling nutrition.

More precisely, we examined the variations in ECM colonization between sites in relation to regeneration status, harvesting practices, and environmental conditions (i.e., topography, meteorological conditions, and soil properties). We hypothesized that: (i) seedlings from the sites with regeneration failures could have a lower ectomycorrhizal colonisation and a lower diversity of ectomycorrhizal exploration types; (ii) ectomycorrhizal colonisation could be lower in clear-cuts than forests due to the loss of inoculum; and (iii) ECM fungi could modify root development, and could lead to better needle nutrient concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

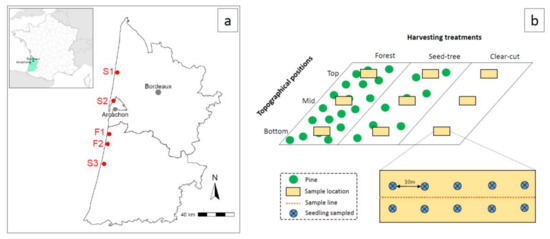

To test our hypotheses, we established trials in five forests along the coast in SW France (Figure 1a). Two of the sites are within the area of chronic stand regeneration failure (hereafter referenced to as sites F1 and F2), while the three other sites are in areas with high values of regeneration success (S1, S2, and S3). Since regeneration failures are very heterogeneous within the same forest, germination and survival were monitored during the three years following the clear-cut to confirm the regeneration status of the sites (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the five study sites (a) and the seedling sampling design (b).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the five study sites.

The climate in the region is temperate oceanic. Annual average precipitations varied from 840 mm to 1007 mm and annual average temperature was around 14 °C for all sites (2006−2016, Météo-France data; Table 1). The year of germination and early growth of seedlings (i.e., 2015) was the driest year of the decade, with precipitations between 608 mm and 880 mm, and average annual temperatures around 14 °C (Météo-France data; Table 1). All sites are near a monospecific forest of Pinus pinaster (Aït in Soland), with some small individuals of oak (Quercus robur L., Q. ilex L., and Q. suber L.) within the stands or in the margins. Understorey was mainly composed of Arbutus unedo L., as well as small amounts of other shrubs (Ulex Europaeus L., Cytisus scoparius (L.) Link), grasses (Holcus lanatus L., Deschampsia flexuosa (L.) Trin.), and ericaceous plants (Erica cinerea L., Erica scoparia L.). All sites were chosen on westerly facing slopes at about 2.5 km from the ocean, with an average slope of 10°. Soils were young sandy soils (WRB (World Reference Base) classification: arenosols; USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) classification: entisols), developed from Aeolian deposits that occurred during the Holocene period [44]. These soils are mainly composed of coarse sands (96−97%), are slightly acidic (topsoil values of pH = 4.5–5.0; base saturation = 32−54%), have a low water holding capacity, and are extremely poor in nutrients [44]. Forest floor organic layer thickness varies between 0.5 and 4 cm (unpublished data [44]).

2.2. Tree Harvesting and Stand Regeneration Management Methods

Because tree harvesting and regeneration methods may impact ECM communities, the three following treatments were tested at each site: (1) control (i.e., no tree harvest and stand disturbance; hereafter referred to as “Forest” treatment); (2) seed-tree regeneration method (i.e., natural regeneration with seed-trees (70 trees ha−1; “Seed-tree” treatment); and (3) clear-cut, which corresponds to the dominant harvesting and regeneration method in coastal dune forest (“Clear-cut” treatment). Logging was carried out mechanically between December 2014 and March 2015 in the seed-tree and clear-cut treatments. Other current practices were carried out before logging in these two treatments: understorey vegetation was mechanically removed to limit post-logging competition, and was combined with mechanical tillage to increase soil aeration and the availability of nutrients. This tillage mixed the forest floor organic layers with the mineral topsoil layer.

Light availability for each harvesting treatment was calculated from the diameter, age, and density of the trees, following equations of Porté et al. [45] and Berbigier and Bonnefond [46]. It was significantly different between harvesting treatments (Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, p = 0.002), with the lowest values in forests (mean: 80 ± 2.2%), intermediate values in seed-trees (mean: 92 ± 0.7%), and maximal values in clear-cuts (mean: 100%) (Tukey test: a, b, and c, respectively).

2.3. Sampling of Seedlings

In this study, we chose to sample seedlings that had regenerated naturally rather than planting nursery grown seedlings, in order to remain as close as possible to natural regeneration conditions. Indeed, ECM communities between seedlings planted under nursery conditions and those that had regenerated naturally in the stand are different [14]. The nursery fungi suppress the initial colonization by native fungi, and do not reflect a difference in local inoculum [32]. Seedlings were selected and sampled from all five sites between the end of November 2015 and early February 2016. Seedlings almost only germinate in spring (between the end of March and the beginning of June), and were eight to 10 months old when sampled. At each site, for each harvesting treatment and for each topographical position, a central area of about 50 m × 8 m was identified for seedling sampling (=9 areas per site; Figure 1b). Within each area, two seedlings were selected every 10 m as close as possible to the line splitting the area in half, with one on each side of the line (Figure 1b). Non-browsed seedlings were selected (between 5 and 20 cm in height). Areas too close to other tree species (especially oaks) were avoided. Seedlings with their entire root system and a small amount of soil were gently removed using a shovel and then stored in plastic bags at 4 °C. In total, 450 seedlings were sampled (450 = 5 sites × 3 harvest treatments × 3 topographical positions × 10 seedlings).

2.4. Assessment of Seedling Dimensions and Ectomycorrhizal Status

Seedlings were cut at the root collar. Shoot stem diameter and total height were measured. Roots were then washed carefully over a plastic tray to remove soil adhering to the roots without disrupting the ECM material. Tap root length was recorded. Then, roots were divided into coarse roots (CR, diameter > 2 mm) and fine roots (FR, diameter < 2 mm). CR Lengths were measured with a caliper. For FR, we calculated mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal root length based on the line intersect method [47]. Root tips were observed using a binocular microscope, and ECM fungi were classified into the four main morphotypes reported by Agerer [20], depending on the exploration type of fungi. Contact exploration types have a smooth mantle, sometimes with a few hyphae. Short-distance exploration types correspond to ECM with many hyphae and no rhizomorphs. Medium-distance exploration types are represented by fungae with hyphae and rhizomorphs, which ramify and interconnect repeatedly. Long-distance exploration types include smooth ECM with few but highly differentiated rhizomorphs [20]. Non-mycorrhizal root tips were also counted. Shoots, CR, and FR samples were dried at 60 °C to obtain biomass values. ECM root colonization (%), specific root length (SRL, m g−1), total seedling biomass (g), root:shoot (R:S, g g−1), and height:diameter (H:D, mm mm−1) ratios were calculated from these measurements. Measurements from the ten seedlings from each sample location (same harvest treatment and same topographical position) were averaged for statistical analyses.

2.5. Needle Nutrient Concentrations

Needles from the ten seedlings of each sample location were grouped into a composite sample (n = 45 composite samples) for mineral analysis (N, P, K, Mg, Ca). Nutrient concentrations were analysed after digestion in sulphuric acid and hydrogen peroxide. Nitrogen and phosphorus were determined colorimetrically with a Technicon auto analyser II. Potassium, calcium, and magnesium were determined with a Varian SpectrAA-20 flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Varian, Mulgrave, Australia).

Nutrient concentration values were compared to two sufficiency thresholds (i.e., where growth is medium to good) from a literature compilation by van den Burg [48]. These thresholds correspond to the mean values of several pine species, discerning values obtained from studies in sand culture from those in pot trials (Supplementary Materials, Table S1).

2.6. Data Treatments and Statistics

All statistical analyses were realised with R software version 3.4.1. [49].

2.6.1. ECM Status

ECM root colonization, expressed as a percentage, was logit-transformed following Warton and Hui [50] and total ECM root tips and number of root tips for each exploration type were expressed as number per meter of fine root length.

First, we scrutinized potential differences of ECM status between sites and according to meteorological differences between the sites. Analysis of variance was used to compare ECM status between sites, using data for all seedlings from all treatments within each site. Correlations between ECM variables and site characteristics (pH, OM, and precipitation variables) were prospected with Bravais-Pearson correlation tests.

To investigate variations of ECM status within the different sites according to harvesting treatments and topography, we used linear mixed modelling with harvesting treatment and topography as fixed effects, and the site as a random effect. Posthoc Tukey pairwise multiple comparisons were performed for significant treatments.

2.6.2. Seedling Growth and Nutrient Concentrations

To analyse how seedling growth and nutrient concentrations were affected by harvesting treatment and topography, we carried out linear mixed models with harvesting treatment and topography as fixed effects, and the site as a random effect. Biomass values and fine root length were log-transformed to reach linear modelling assumptions. The date of emergence of the seedlings, which may have varied by a few weeks, could lead to differences in terms of seedling size and the allocation of carbon and nutrients are both known to vary with plant size and ontogeny [51]. Thus many seedling characteristics (root:shoot, height:diameter, specific root length, and plant nutrient concentrations) were expected to vary with seedling size [52,53,54]. Consequently, to take this effect due to seedling size into account when performing our analyses, we first carried out linear regressions between aboveground biomass and these variables. In a second step, when regressions were significant (p < 0.001 for R:S, H:D, N, P, K and Ca, p = 0.97 for Mg, p = 0.72 for SRL), the effects of harvesting treatment and topography were prospected on regression residuals and residual variance. Posthoc Tukey pairwise multiple comparisons were performed for significant factors.

2.6.3. Relationship between ECM and Seedling Response after Filtering out Effects of Harvesting Treatments and Topographical Positions

As ECM can improve access to soil resources for seedlings, analyses were only performed for the following variables related to soil resource availability and plant nutrition: root:shoot ratio (R:S), specific root length (SRL), and nutrient concentrations. The investigation of relationships between ECM and seedling characteristics cannot be carried out directly because seedling response can be influenced either as the result of mycorrhizal colonisation, or the impact of environmental variations on both seedlings and mycorrhizae. Our previous statistical models performed in 2.6.2 had taken the effects related to seedling size and local environment (harvest treatments and topography) into account. Therefore, using the residual variance of these models enabled us to focus on the potential remaining relationship between ECM and seedling properties alone, having filtered out the other aforementioned effects.

3. Results

3.1. Sites

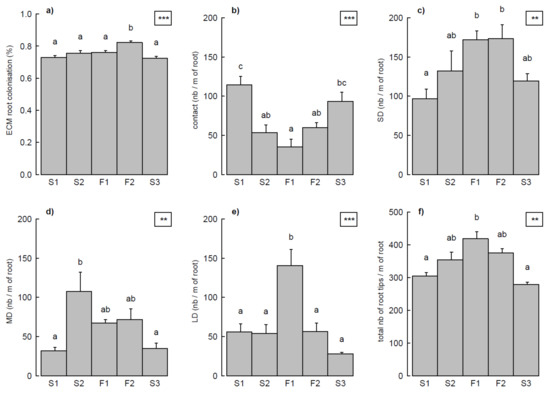

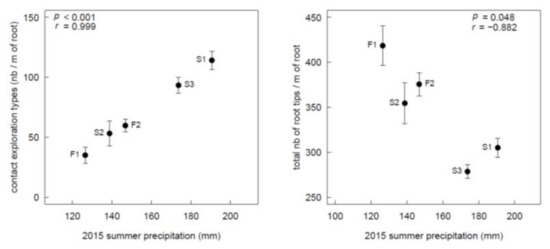

The four exploration types were observed at all sites, and throughout most of the individual root systems examined; 73% and 25% of the seedlings had respectively four and three exploration types on their root system. ECM root colonization (%), number of root tips of each exploration type (nb m−1), and total root tips differed in the five study sites (Figure 2; all p-values < 0.01). Root colonization was higher in F2. Contact exploration type was higher in S1 and S3, whereas short-distance exploration types were more prevalent in F1 and F2. The largest numbers of medium- and long-distance exploration types were found respectively in S2 and F1. The greatest number of root tips occurred in F1, followed by F2/S2 and S1/S3 (decreasing order; Figure 2f). Contact exploration types and total number of root tips were respectively positively and negatively linked to summer 2015 precipitations (Figure 3), but no effects of annual or decennial rainfall were observed. Medium-distance exploration types were positively correlated with soil pH (r = 0.978, p = 0.004).

Figure 2.

Differences in ectomycorrhizal (ECM) root colonization (a), the four ECM exploration types (b–e; expressed as the number of root tips per meter of root length), and total root tips (f) in the five study sites. Each bar represents mean ± SE (standard error) of nine values per site (harvesting treatments and topographical positions combined). Statistical significance is shown in the top right corner of each plot (***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences between sites (p < 0.05, Tukey test). SD, MD, and LD stand for short-distance, medium-distance, and long-distance exploration types, respectively.

Figure 3.

Significant (p < 0.05) Pearson correlations between ECM variables and summer precipitation (precipitation from July to September).

3.2. ECM Status Related to Harvesting Treatments and Topographical Positions

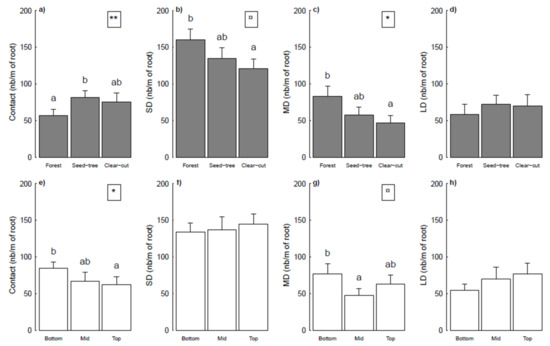

ECM root colonization ranged from 64.8% to 87.3% (mean 75.8 ± 0.7%) and was not impacted by harvesting treatment (p = 0.288) or by topography (p = 0.619). No significant relationship was observed between total number of root tips and harvesting treatments (p = 0.131) or topography (p = 0.514) either. Harvesting treatment (Figure 4a) and topography (Figure 4b) had a significant effect on ECM status. Contact (p = 0.008), short-distance (p = 0.052), and medium-distance (p = 0.011) exploration types were significantly affected by harvesting treatment (Figure 4a), but not long-distance exploration types (p = 0.506). Numbers of short- and medium-distance root tips were higher on seedlings in forests and smaller on those in clear-cuts. Seedlings in seed-trees had a greater number of contact exploration than those in forests. Topography significantly affected the number of contact (p = 0.021) and medium-distance (p = 0.063) exploration types (Figure 4b). Contact exploration decreased from bottom positions to top positions, whereas medium-distance exploration was higher in the bottom position than in the mid position.

Figure 4.

Number of root tips per meter of root length for the four ectomycorrhizal exploration types, under (a) three harvesting treatments and (b) three topographical positions. Each bar represents an average of 15 ± SE values. Significance of harvesting treatments or topographical positions is shown in the top right corner of each plot (**, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ¤, p < 0.1). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences for the same ECM exploration type between harvesting treatments (a–d) or topographical positions (e–h) at p < 0.05, Tukey test. SD, MD, and LD stand for short-distance, medium-distance, and long-distance exploration types, respectively.

3.3. Seedling Growth and Needle Nutrient Concentrations

All parameters except specific root length (SRL) and Mg-needle concentration were significantly affected by harvesting treatment (p = 0.430 for SRL, p = 0.712 for Mg, p < 0.001 for all others; Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of harvesting treatments and topographical positions on growth variables and needle nutrient concentrations.

Total seedling biomass and shoot biomass, stem diameter, and tap root length increased with a decreasing intensity of harvesting, from the forest to the clear-cut. Root biomass and fine root length were the lowest in forests, but no differences were found between seed-trees and clear-cuts. Seedling height was greater for seedlings growing in forests. Regarding needle nutrient concentrations, N and P were higher in seedlings in clear-cuts than in seed-trees, which were in turn higher than those in forests. K concentration was lower in forests than in seed-trees and clear-cuts. Ca concentration was higher in needles from seed-tree seedlings than in clear-cuts and forests. Topography only affected SRL (p = 0.017), seedling height (p = 0.038), and height:diameter ratio (p = 0.007), which were all greater at the mid position than the top position (Table 2). Regarding thresholds of sand culture studies, N and P concentrations in forest seedlings were under the threshold, while none of the other nutrients were considered as deficient in seed-trees or clear-cuts regardless of their topographical positions (Table 2). Using threshold values derived from pot trial studies, K and Ca concentrations were also deficient in the forest, whereas Ca was below the threshold for both seed-cuts and clear-cuts for all topographical positions.

3.4. Effects of ECM on Seedling Root Properties and Nutrient Concentrations

SRL was highly affected by ECM composition but not root:shoot ratio (Table 3). The contact exploration type showed a positive effect on SRL, whereas other exploration types (short-, medium-, and long-distances) and total number of root tips were related to a decrease in SRL values. With regards to plant nutrient concentrations, several relationships were significant (Table 3), most of them showing an improvement in nutritive status of seedlings. Ca, K, and N needle concentrations significantly increased respectively with number of contacts, and short- and long-distance exploration types, whereas a higher number of the medium-distance exploration type corresponded to a decrease in Ca concentration. Total number of root tips was positively linked to higher N, K, and Mg concentrations.

Table 3.

Results of linear regression between ECM colonization, root properties, and needle nutrient concentrations after removing effects due to harvesting treatments, topographical positions, and seedling size.

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Abiotic Factors in ECM Composition

Two results confirmed the influence of soil moisture and hence water availability on ECM composition: (i) the influence of summer rainfall at the site and (ii) the influence of topography.

Significant differences in all ECM characteristics were observed among sites, suggesting that the local environment plays an important role in shaping ECM communities. Correlation between site environmental variables and ECM exploration types showed the positive influence of the summer rainfall during the first growing year on the number of contact exploration types and a negative effect on the total number of root tips (Figure 3). These results suggest that meteorological conditions during the first months of establishment are more important than the historical climatic conditions at the sites. Contact exploration types, which are less carbon costly for the seedling, take up water more efficiently during rainfall events thanks to their hydrophilic mantle [20]. Conversely, seedlings develop more root tips in drier areas [55], which may increase mycorrhizal associations. Rainfall and soil water availability have been shown to be an important factor governing fungal communities [25,56,57,58], but mainly by studying ECM species composition instead of exploration types. Jarvis et al. [29], who looked at both species and exploration types in Pinus sylvestris across Scotland, found that soil moisture and precipitation were the main drivers of ECM species composition, while temperature had an influence on exploration types. In our study, we could not test a link with temperature because of the small variation between our sites (less than 0.7 °C differences for all temperature variables). Conversely, we found that summer precipitation had a strong influence on ECM composition with higher contact exploration types at the wettest sites.

Regarding topography, a greater number of contact exploration types were shown at the bottom position than the top position. These results could be explained by higher water [43] and nutrient availabilities in the lower topographical positions [59], where the contact exploration types are more suitable because of their hydrophilic mantle, which allows them to be in closer contact with resources [20]. We expected the opposite pattern for long-distance exploration types which develop over a larger area and have greater mycelial expansion [20]. They are more likely to develop in stressful areas, but in our case, even though they tend to be more abundant at the top positions, the relationship was not significant. These results can be related to those observed by Bakker et al. [22] from two mature stands of maritime pines varying in distance from the water table and nutrient availability. They found a greater proportion of contact exploration types at the wet nutrient rich site and a higher proportion of long-distance types at the dry nutrient poor site.

Another positive significant correlation was found between pH and medium-distance explorations. A shift in ECM composition, from species developing high extramatrical mycelium instead of smooth types when pH increased, has already been reported in field survey studies (e.g., [60]) or liming experiments (e.g., [61]).

4.2. Impact of Forest Management on ECM Composition

In contradiction with our second hypothesis, we did not find any decrease of fungal root colonization with harvesting treatment, suggesting that the amount of fungal inoculum is still sufficient for the establishment of new seedlings the year after logging. It has been shown that forest practices similar to those used in our study may have a positive influence on ECM colonisation, and this may explain our results. More precisely: (i) mechanical soil disturbance leaving organic matter in the topsoil layers may have less impact than those that remove or bury the organic layer [33]; (ii) letting stumps in the forest stand during harvesting can have a positive impact on the maintenance of higher levels of fungal inoculum [34]; and (iii) tree harvesting occurring in late autumn or winter also allows mycorrhizae to remain active longer in the soil [32].

We expected a potential gradient of soil moisture which decreases from forests to clear-cuts due to the microenvironment created by the canopies of the trees, and that this soil moisture could impact ECM composition (leading to a greater number of contact exploration types in forests and long-distance exploration types in clear-cuts). Instead, differences found between forests and seed-trees/clear-cuts in ECM composition indicated that logging and site preparation influenced ECM composition in a different way. During our binocular observations, we often found patches of contact exploration types encrusted in small pieces of decaying wood. Contact exploration types are known to develop more in soil with high organic matter content, being able to degrade lignin directly from dead wood or rotting leaves to increase access to nutrients [20]. The mechanical tillage used in the study sites probably incorporated a supply of dead wood into the topsoil layers, which could explain the greater number of contact exploration types in seed-trees and clear-cuts. Another explanation for this increase in contact exploration is the higher resilience of these exploration types to disturbance, because they can easily regenerate their reduced system of extramatrical hyphae [62]. Conversely, short- and medium-distance exploration types with a lot of hyphae and some rhizomorphs decreased, due to the increasing harvesting intensity. In addition to the lower resilience of these ECM, the growth of nearby mature trees could influence ECM colonization for new seedlings. Trees may maintain greater mycelial networks from which fungi could vegetatively colonize new hosts due to the close vicinity of their roots [14,41,63]. This could be potentially more effective for exploration types with emanating hyphae. It has also been shown that ECM fungal propagules decreased sharply when isolated from a potential source, leading to a decrease in fungal colonization and diversity [64].

4.3. Impact of Forest Management on Seedling Characteristics

Morphological traits of seedlings were strongly impacted by harvesting treatment (15 out of the 17 variables studied showed significant differences; Table 2). As we had assumed, our results confirmed the light demanding characteristics of Pinus pinaster seedlings, which had higher above and below ground tissues, a greater stem diameter, and higher needle nutrient concentrations in clear-cuts than in forests. As shown by Robakowski et al. [65], seedlings growing under a higher level of light show greater net CO2 assimilation rates and higher daily maximal photosynthetic rates, leading to a higher shoot biomass when light increases [66,67,68,69,70]. The observed increase of stem height and stem height:diameter ratio can also be interpreted as a shade avoidance response and are in agreement with previous results regarding these seedling traits [66,68,71,72].

Root biomass is also known to be improved in high light environments, but results regarding root:shoot ratio variations were heterogeneous, especially in the early stages. In Pinus pinaster seedlings, Rodríguez-García and Bravo [68] showed a higher allocation to roots when light increased in a garden experiment, whereas Ruano et al. [69] found no variations in root:shoot ratios in a field study with four harvesting intensities. These discrepancies may be due to differences in seedling size which affect root:shoot ratios [51]. The increase of tap root length from forests to clear-cuts is probably due to soil moisture differences between harvesting treatments; seedlings in dry areas improve their water foraging capacity by having long and deep roots [73,74].

Seedlings growing in forests had lower needle nutrient concentrations. Higher N and P concentrations in clear-cuts than in seed-trees could also be related to better nitrogen and phosphorus efficiency use in full light than in low light, as reported by Elliott and White [67]. In addition, the mechanical effect of logging and soil preparation carried out in clear-cuts and seed-trees could explain our results, as these can lead to an increase of mineralisation, thus causing a substantial release of mineral elements into the soil.

Overall, the sufficient level of nutrients observed in needles of our seedlings suggests that mycorrhizae may enable seedlings to overcome the nutritional stress of the local environment (Table S1).

4.4. Effects of ECM on Seedling Root Development and Nutritive Status

ECM colonisation is associated with a modification in fine root morphology according to the different exploration types rather than a greater investment to the roots (Table 3). Mycorrhizal colonisation usually increases both shoot and root biomass, but the root:shoot ratios could be lower or higher in conifer seedlings depending on the amount of fungal tissue present [13,75]. Indeed, the ECM fungal identity is the main factor determining fine root morphology [76] and aboveground biomass variations [77]. ECM colonisation increased fine root diameter and decreased SRL, especially due to the mycelial mantle surrounding fine roots [12,13]. High SRL values suggest fast growth and intensive soil exploration. Thus, seedlings with lower SRL values will need more root tips and exploration types with a lot of hyphae or rhizomorphs to compensate for the lower soil exploration area.

Plant nutrient concentration is greater with more root tips, and each exploration type is significantly associated with a single nutrient (Table 3). These results are consistent with our third hypothesis, and suggest that different functional types appear to be complementary for access to different nutrient sources. Several studies looking at functional diversity showed relationships with soil properties and nutrient availability, especially N [21,23,29,30]. Long-distance exploration types are able to prevent resources from leaching during transport with their hydrophobic rhizomorphs and would have a strong ability to acquire organic N [23]. However, this strategy is expensive in energy for the plant and thus such a strategy is competitively dominant only in lower nutrient environments where resources are rare and patchy, as in our sites. Our findings can be related to those of de Witte et al. [30], who investigated ECM exploration types in several beech forests and found many correlations between exploration types and foliar concentrations or soil properties. Similar to our results, they showed a positive relationship between contact exploration types and soil Ca (soil and foliar Ca were positively correlated in the study), together with a negative relationship between medium-distance exploration types and soil Ca. Furthermore, they found that a higher abundance of medium- and long-distance types was negatively associated with foliar N, and suggested that this might be due to the non N-limited environment in their study.

4.5. Can ECM Explain Failures of Forest Regeneration?

In the case where mycorrhization could be a factor involved in regeneration failures, we would expect that sites in failure areas (F1 and F2) would have insufficient mycorrhization (in terms of root colonization or number of root tips), or would have a clearly different composition of ECM communities. However, failure sites have higher numbers of root tips and higher or equivalent root colonization, which is contrary to our first hypothesis. The four exploration types were found on seedlings at all sites and only the short-distance ones discriminated failure areas from successful areas in terms of exploration type composition (Figure 2c). However, this exploration type was not specific of failure sites because it corresponded to the more prevalent exploration type at four of the five sites (and the second highest in S1). The prevalence of the short-distance exploration type could be explained by the fungal identity which is the most representative of this exploration type, Cenococcum geophilum, and by the summer drought conditions occurring in our region. This species is known to be drought-tolerant and extremely resilient after drought [78], allowing an early uptake of water and nutrients in the post-drought period [79]. In addition, fast colonization of new seedlings could also be the result of frequent disturbances within these forests (fires, storms), which has been shown to lead to an early-seral ECM community (of which Cenococcum is a part) necessary to promote seedling establishment [35].

A high diversity of exploration types was observed at all sites and throughout most of the individual root systems. This diversity may promote a higher resilience of ECM communities to environmental changes, and suggests that fungal association is essential for the survival of young seedlings in the region even though it does not explain the failure of regeneration in some specific areas. However, we should consider that by harvesting the seedlings during their first winter, we only have seedlings that have survived the dry summer conditions, which is probably the main cause of mortality in the early establishment of maritime pine seedlings [38]. Seedlings with lower mycorrhizal associations in both quantity and/or exploration type diversity (and Cenococum geophilum in particular) may have died during the summer season and are thus missing from our sample, and this may be the main limit of our study.

5. Conclusions

Our results showed that ECM composition was affected by both harvesting and topography. In turn, mycorrhization appeared to be essential for early seedling establishment by improving the nutritive status of seedlings. However, in our context, ECM colonisation one year after logging does not seem to be linked to regeneration failures that occur in some specific areas. Other kinds of biotic interactions such as facilitation/competition with other plants or herbivory should also be explored to understand such regeneration failures.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/9/5/245/s1. Table S1: nutrient threshold for pine seedlings (A) in sand culture or (B) in pot trial, from van der Burg [48].

Author Contributions

A.G. and M.R.B. designed and performed the experiments; A.G. and F.D. analyzed the data; A.G., F.D., M.G., L.A., and M.R.B. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathalie Gallegos and Cathy Lambrot for soil and nutrient concentration analyses, Météo-France and Benoît Persyn for meteorological data acquisition, Aldyth Nys for revising the English, and three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on the manuscript. We are very grateful to the “Office National des Forêts” (ONF), in particular Didier Canteloup, Francis Maugard, and all staff working on the management of the study sites for the valuable help provided. The ONF staff were in charge of the implementation of seed-tree and clear-cut harvesting treatments. A. Guignabert was funded by a PhD grant by the Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine and Bordeaux Sciences Agro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IFN Inventaire Forestier National. Available online: https://inventaire-forestier.ign.fr/ (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- Sardin, T. Guide des Sylvicultures Forêts Littorales Atlantiques Dunaires, ONF ed.; Office National des Forêts: Paris, France, 2009; p. 175. ISBN 9782842073374. [Google Scholar]

- Ouallet, P. Quels Peuvent-être les Facteurs Écologiques Responsables des Échecs de Régénération Naturelle du pin Maritime sur les Dunes Littorales des Forêts Domaniales de Biscarrosse et de Sainte-Eulalie? Master’s Thesis, Bordeaux Sciences Agro et ONF, Gradignan, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.S.; Macklin, E.; Wood, L. Stages and Spatial Scales of Recruitment Limitation in Southern Apalachians forests. Ecol. Monogr. 1998, 68, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, K.; Fenner, M. Ecology of seedling regeneration. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 331–359. ISBN 0851994326. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A.E.; Jurgensen, M.F.; Larsen, M.J.; Graham, R.T. Relationships among soil microsite, ectomycorrhizae, and natural conifer regeneration of old-growth forests in western Montana. Can. J. For. Res. 1987, 17, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, R. The effect of plant competition and simulated summer browsing by deer on tree regeneration. J. Appl. Ecol. 2001, 38, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, E.; Gratzer, G.; Bravo, F. Climatic variability and other site factor influences on natural regeneration of Pinus pinaster Ait. in Mediterranean forests. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.A.; Molina, R.; Amaranthus, M.P. Mycorrhizae, mycorrhizospheres, and reforestation: Current knowledge and research needs. Can. J. For. Res. 1987, 17, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.L.; McClean, T.M.; Stanton, N.L.; Williams, S.E. Mycorrhization, physiognomy, and first-year survivability of conifer seedlings following natural fire in Grand Teton National Park. Can. J. For. Res. 1998, 28, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.S.; Simard, S.W.; Jones, M.D.; Durall, D.M. Ectomycorrhizal fungal community assembly on regenerating Douglas-fir after wildfire and clearcut harvesting. Oecologia 2013, 172, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, J.V.D.; Sylvia, D.M.; Fox, A.J. Contribution of ectomycorrhiza to the potential nutrient-absorbing surface of pine. New Phytol. 1994, 128, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780123705266. [Google Scholar]

- Teste, F.P.; Simard, S.W.; Durall, D.M.; Guy, R.D.; Jones, M.D.; Schoonmaker, A.L. Access to mycorrhizal networks and roots of trees: Importance for seedling survival and resource transfer. Ecology 2009, 90, 2808–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, R.; Garbaye, J. Influence of ectomycorrhizae on infectivity of Pythium-infested soils and substrates. Plant Soil 1983, 71, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tichelen, K.K.; Colpaert, J.V.; Vangronsveld, J. Ectomycorrhizal protection of Pinus sylvestris against copper toxicity. New Phytol. 2001, 150, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, T.; Zwiazek, J.J. Ectomycorrhizas and water relations of trees: A review. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousain, D. Effets de deux facteurs edaphiques (teneur en phosphore et qualite de la matiere organique des sols) sur l’etablissement de la symbiose ectomycorhizienne du pin maritime (Pinus pinaster Soland. in Ait.). Rev. Ecol. Biol. Sol 1975, 12, 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- Read, D.J.; Leake, J.R.; Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizal fungi as drivers of ecosystem processes in heathland and boreal forest biomes. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R. Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae: A proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance. Mycorrhiza 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleskov, E.A.; Hobbie, E.A.; Horton, T.R. Conservation of ectomycorrhizal fungi: Exploring the linkages between functional and taxonomic responses to anthropogenic N deposition. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.R.; Augusto, L.; Achat, D.L. Fine root distribution of trees and understory in mature stands of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) on dry and humid sites. Plant Soil 2006, 286, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Agerer, R. Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slankis, V. Soil Factors Influencing Formation of Mycorrhizae. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1974, 12, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Sakai, A.; Hattori, M.; Nara, K. Strong effect of climate on ectomycorrhizal fungal composition: Evidence from range overlap between two mountains. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, F.; Barsoum, N.; Lilleskov, E.A.; Bidartondo, M.I. Nitrogen availability is a primary determinant of conifer mycorrhizas across complex environmental gradients. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpeläinen, J.; Barbero-López, A.; Vestberg, M.; Heiskanen, J.; Lehto, T. Does severe soil drought have after-effects on arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal root colonisation and plant nutrition? Plant Soil 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Nguyen, N.H.; Stefanski, A.; Han, Y.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A.; Reich, P.B.; Kennedy, P.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal response to warming is linked to poor host performance at the boreal-temperate ecotone. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, S.; Woodward, S.; Alexander, I.J.; Taylor, A.F.S. Regional scale gradients of climate and nitrogen deposition drive variation in ectomycorrhizal fungal communities associated with native Scots pine. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 1688–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witte, L.C.; Rosenstock, N.P.; van der Linde, S.; Braun, S. Nitrogen deposition changes ectomycorrhizal communities in Swiss beech forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.E.; Jurgensen, M.F.; Larsen, M.J.; Schlieter, J.A. Distribution of Active Ectomycorrhizal Short Roots of the Inland Northwest: Effects of Site and Disturbance; INT-374; Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1986; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.D.; Durall, D.M.; Cairney, J.W.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in young forest stands regenerating after clearcut logging. New Phytol. 2003, 157, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaruk, L.W.; Macdonald, S.E.; Kernaghan, G. The effect of mechanical site preparation on ectomycorrhizae of planted white spruce seedlings in conifer-dominated boreal mixedwood forest. Can. J. For. Res. 2008, 38, 2072–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-Dumroese, D.S.; Harvey, A.E.; Jurgensen, M.F.; Amaranthus, M.P. Impacts of soil compaction and tree stump removal on soil properties and outplanted seedlings in northern Idaho, USA. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1998, 78, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranabetter, J.M.; Haeussler, S.; Wood, C. Vulnerability of boreal indicators (ground-dwelling beetles, understory plants and ectomycorrhizal fungi) to severe forest soil disturbance. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 402, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaruk, L.W.; Kernaghan, G.; Macdonald, S.E.; Khasa, D. Effects of partial cutting on the ectomycorrhizae of Picea glauca forests in northwestern Alberta. Can. J. For. Res. 2005, 35, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Twieg, B.D.; Durall, D.M.; Berch, S.M. Location relative to a retention patch affects the ECM fungal community more than patch size in the first season after timber harvesting on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, E.; Bravo, F.; Spies, T.A. Effects of overstorey canopy, plant–plant interactions and soil properties on Mediterranean maritime pine seedling dynamics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, M.A.; Simard, S. Ectomycorrhizal Networks of Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca Trees Facilitate Establishment of Conspecific Seedlings under Drought. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.M.; Brooks, J.R.; Meinzer, F.C.; Eberhart, J.L. Hydraulic redistribution of water from Pinus ponderosa trees to seedlings: Evidence for an ectomycorrhizal pathway. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, L.; Dahlberg, A.; Nilsson, M.C.; Kårén, O.; Zackrisson, O. Continuity of ectomycorrhizal fungi in self-regenerating boreal Pinus sylvestris forests studied by comparing mycobiont diversity on seedlings and mature trees. New Phytol. 1999, 142, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, A.; Schimmel, J.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Johannesson, H. Post-fire legacy of ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in the Swedish boreal forest in relation to fire severity and logging intensity. Biol. Conserv. 2001, 100, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitaud, G. L’hydrogéologie et la Végétation dans les Dunes du Littoral Aquitain. Ph.D. Thesis, University Bordeaux, Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Augusto, L.; Bakker, M.R.; Morel, C.; Meredieu, C.; Trichet, P.; Badeau, V.; Arrouays, D.; Plassard, C.; Achat, D.L.; Gallet-Budynek, A.; et al. Is “grey literature” a reliable source of data to characterize soils at the scale of a region? A case study in a maritime pine forest in southwestern France. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2010, 61, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porté, A.; Bosc, A.; Champion, I.; Loustau, D. Estimating the foliage area of Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aït.) branches and crowns with application to modelling the foliage area distribution in the crown. Ann. For. Sci. 2000, 57, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbigier, P.; Bonnefond, J. Measurement and modelling of radiation transmission within a stand of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait). Ann. Sci. For. 1995, 52, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, D. A test of a modified line intersect method of estimating root length. J. Ecol. 1975, 63, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Burg, J. Foliar Analysis for Determination of Tree Nutrient Status: A Compilation of Literature Data; Rijksinstituut voor Onderzoek in de Bos-en Landschapsbouw de Dorschkamp: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2017).

- Warton, D.I.; Hui, F.K.C. The arcsine is asinine: The analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 2011, 92, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnaughay, K.D.M.; Coleman, J.S. Biomass Allocation in Plants: Ontogeny or Optimality? A Test along Three Resource Gradients. Ecology 1999, 80, 2581–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, D.L.; Deleuze, C.; Landmann, G.; Pousse, N.; Ranger, J.; Augusto, L. Quantifying consequences of removing harvesting residues on forest soils and tree growth—A meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 348, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, L.; Ranger, J.; Ponette, Q.; Rapp, M. Relationships between forest tree species, stand production and stand nutrient amount. Ann. For. Sci. 2000, 57, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritson, P.; Sochacki, S. Measurement and prediction of biomass and carbon content of Pinus pinaster trees in farm forestry plantations, south-western Australia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 175, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, R.; Simon, J.; Rennenberg, H.; Polle, A. Ectomycorrhiza affect architecture and nitrogen partitioning of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) seedlings under shade and drought. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 87, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Toots, M.; Diédhiou, A.G.; Henkel, T.W.; Kjøller, R.; Morris, M.H.; Nara, K.; Nouhra, E.; Peay, K.G.; et al. Towards global patterns in the diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 4160–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Zarre, S.; Tedersoo, L. Regional and local patterns of ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity and community structure along an altitudinal gradient in the Hyrcanian forests of northern Iran. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Guttenberger, M.; Kottke, I.; Hampp, R. The effect of drought on mycorrhizas of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.): Changes in community structure, and the content of carbohydrates and nitrogen storage bodies of the fungi. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewerniak, P.; Jankowski, M. Topographically-controlled site conditions drive vegetation pattern on inland dunes in Poland. Acta Oecol. 2017, 82, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, A.; Ellström, M.; Akselsson, C.; Ekblad, A.; Mikusinska, A.; Wallander, H. Growth of ectomycorrhizal fungal mycelium along a Norway spruce forest nitrogen deposition gradient and its effect on nitrogen leakage. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 59, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.; Garbaye, J.; Nys, C. Effect of liming on the ectomycorrhizal status of oak. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 126, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Smith, M.E. Lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi revisited: Foraging strategies and novel lineages revealed by sequences from belowground. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2013, 27, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, E.T.; Ammirati, J.F.; Edmonds, R.L. Does proximity to mature trees influence ectomycorrhizal fungus communities of Douglas-fir seedlings? New Phytol. 2005, 166, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peay, K.G.; Schubert, M.G.; Nguyen, N.H.; Bruns, T.D. Measuring ectomycorrhizal fungal dispersal: Macroecological patterns driven by microscopic propagules. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 4122–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robakowski, P.; Wyka, T.; Samardakiewicz, S.; Kierzkowski, D. Growth, photosynthesis, and needle structure of silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) seedlings under different canopies. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 201, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Klinka, K. Survival, growth, and allometry of planted Larix occidentalis seedlings in relation to light availability. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 106, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.J.; White, A.S. Effects of light, nitrogen, and phosphorus on red pine seedling growth and nutrient use efficiency. For. Sci. 1994, 40, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, E.; Bravo, F. Plasticity in Pinus pinaster populations of diverse origins: Comparative seedling responses to light and Nitrogen availability. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 307, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, I.; Pando, V.; Bravo, F. How do light and water influence Pinus pinaster Ait. germination and early seedling development? For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 2647–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingleby, K.; Munro, R.C.; Noor, M.; Mason, P.A.; Clearwater, M.J. Ectomycorrhizal populations and growth of Shorea parvifolia (Dipterocarpaceae) seedlings regenerating under three different forest canopies following logging. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 111, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, M.A.; Espelta, J.M.; Caspersen, J.; Retana, J. Interspecific differences in sapling performance with respect to light and aridity gradients in Mediterranean pine–oak forests: Implications for species coexistence. Can. J. For. Res. 2011, 41, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.G.; Qian, H.; Klinka, K. Growth of Thuja plicata seedlings along a light gradient. Can. J. Bot. 1994, 72, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markesteijn, L.; Poorter, L. Seedling root morphology and biomass allocation of 62 tropical tree species in relation to drought- and shade-tolerance. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, I.; Herzog, C.; Dawes, M.A.; Arend, M.; Sperisen, C. How tree roots respond to drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, I.J. The Picea sitchensis + Lactarius rufus mycorrhizal association and its effects on seedling growth and development. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1981, 76, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostonen, I.; Tedersoo, L.; Suvi, T.; Lõhmus, K. Does a fungal species drive ectomycorrhizal root traits in Alnus spp.? Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, K. Ectomycorrhizal networks and seedling establishment during early primary succession. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigott, C.D. Survival of mycorrhiza formed by Cenococcum geophilum Fr. in dry soils. New Phytol. 1982, 92, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Gessler, A. Global climate change and tree nutrition: Influence of water availability. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).