Leaf–Litter–Soil C:N:P Coupling Indicates Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Across Subtropical Forest Types

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Plot Selection

2.2. Sampling of Leaves, Litter, and Soils

2.3. Chemical Analyses

2.4. Derived Indices and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. C, N, and P Concentrations and Ratios by Compartment and Forest Type

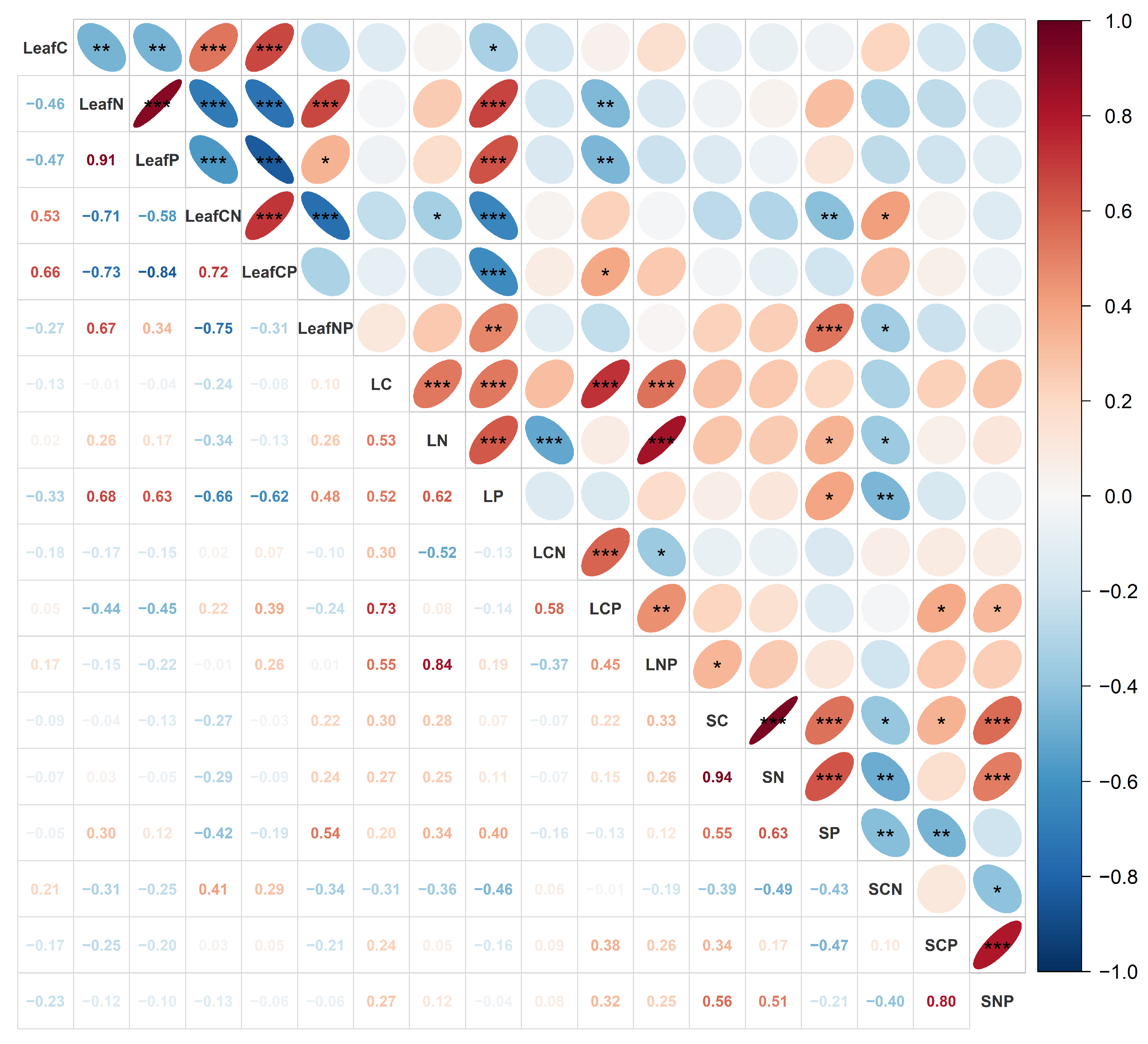

3.2. Cross-Compartment Correlations and Multivariate Patterns

3.3. Leaf–Litter Nutrient Shift and Leaf–Soil Homeostasis

4. Discussion

4.1. Forest-Type Signatures in Leaves and Soils

4.2. Cross-Compartment Coupling and Nutrient Limitation

4.3. Management Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mori, T. The newly proposed threshold for enzymatic stoichiometry: A reliable solution? Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2025, 209, 109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Liu, S.; Schindlbacher, A.; Prescott, C.; Stokes, A.; Whalen, J. Plant-soil interactions in forests: Effects of management, disturbance and climate. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2022, 168, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, D.; Cui, Y.; Sinsabaugh, R.; Schimel, J. Interpreting patterns of ecoenzymatic stoichiometry. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2023, 180, 108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, L.; Cai, Q. Linkages of plant and soil C:N:P stoichiometry and their relationships to forest growth in subtropical plantations. Plant Soil. 2015, 392, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Xu, D.; He, Z. C:N:P stoichiometry of plant, litter and soil along an elevational gradient in subtropical forests of China. Forests 2022, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Z.; Liu, D.; Li, G.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Soil C, N, and P contents and their stoichiometry as impacted by main forest vegetation types in Xinglongshan, China. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Xie, Z. Leaf litter carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus stoichiometric patterns as related to climatic factors and leaf habits across Chinese broad-leaved tree species. Plant Ecol. 2017, 218, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, L.; Ge, X.; Cao, Y.; Shi, J. Leaf litter carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) across China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Weng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Pei, J. Plant–soil–microbial carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus ecological stoichiometry in Mongolian pine-planted forests under different environmental conditions in Liaoning Province, China. Forests 2025, 16, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Bai, S.H.; Chen, J.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Yue, C.; Deng, L.; Zheng, Y.; Bell, S.M.; Hu, Z. Tree species identity drives the vertical distribution of soil carbon and nutrient concentrations in the Loess Plateau, China. Plant Soil. 2024, 501, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, C.; Cui, Y.; Fan, R.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, S. Tree–litter–soil system C:N:P stoichiometry and tree organ homeostasis in mixed and pure Chinese fir stands in south subtropical China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1293439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Yang, B.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X. The carbon and nitrogen stoichiometry in litter-soil-microbe continuum rather than plant diversity primarily shapes the changes in bacterial communities along a tropical forest restoration chronosequence. Catena 2022, 213, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyildiz, T.; Anderson, J.M. Interactions between litter quality, decomposition and soil fertility: A laboratory study. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, S.E. Effects of plant species on nutrient cycling. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1992, 7, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Q.; Gao, D.; Zuo, H.; Ren, R.; Diao, K.; Chen, Z. Enhanced carbon storage in mixed coniferous and broadleaf forest compared to pure forest in the north subtropical–warm temperate transition zone of China. Forests 2024, 15, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Hui, D.; Xing, S.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Deng, Q. Mixed plantations with N-fixing tree species maintain ecosystem C:N:P stoichiometry: Implication for sustainable production. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerselman, W.; Arthur, F.M.M. The vegetation N:P ratio: A new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güsewell, S. N:P ratios in terrestrial plants: Variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, L.; Flynn, D.F.B.; Wang, X.; Ma, W.; Fang, J. Leaf nitrogen:phosphorus stoichiometry across Chinese grassland biomes. Oecologia 2008, 155, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, M.; Wanek, W.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Richter, A.A. Stoichiometric imbalances between terrestrial decomposer communities and their resources: Mechanisms and implications of microbial adaptations to their resources. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R. Nutrient resorption from senescing leaves of perennials: Are there general patterns? J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingbeck, K.T. Nutrients in senesced leaves: Keys to the search for potential resorption and resorption proficiency. Ecology 1996, 77, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.W.; Elser, J.J. Ecological Stoichiometry: The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yan, P.; Arif, M. Examining the stoichiometry of C:N:P:K in the dynamics of foliar-litter-soil within dominant tree species across different altitudes in southern China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 51, e02885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Dong, Q.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, K.; Xu, N.; Yuan, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Response of thinning to C:N:P stoichiometric characteristics and seasonal dynamics of leaf-litter-soil system in Cupressus funebris Endl. artificial forests in southwest, China. Forests 2024, 15, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Ubach, A.; Sardans, J.; Pérez-Trujillo, M.; Estiarte, M.; Peñuelas, J. Strong relationship between elemental stoichiometry and metabolome in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4181–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Taylor, P.; Richter, A.; Porporato, A.; Ågren, G.I. Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Ortiz, P.; Larsen, J.; Olmedo-Alvarez, G.; García-Oliva, F. Control of inorganic and organic phosphorus molecules on microbial activity, and the stoichiometry of nutrient cycling in soils in an arid, agricultural ecosystem. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hai, X.; Shangguan, Z.; Deng, L. Dynamics of soil microbial C:N:P stoichiometry and its driving mechanisms following natural vegetation restoration after farmland abandonment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C.; Melillo, J.M.; Hall, C.A.S. Pattern and variation of C:N:P ratios in China’s soils: A synthesis of observational data. Biogeochemistry 2010, 98, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.; Huang, X.; Xu, H.; Xie, H.; Cheng, X. Patterns and driving mechanism of C, N, P ecological stoichiometry in plant-litter-soil systems of monoculture and mixed coastal forests in southern Zhejiang Province of China. Forests 2023, 14, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y. Leaf–Litter–Soil C:N:P Coupling Indicates Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Across Subtropical Forest Types. Forests 2026, 17, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010068

Wang B, Yu Y, Jiang N, Wang J, Ma Y. Leaf–Litter–Soil C:N:P Coupling Indicates Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Across Subtropical Forest Types. Forests. 2026; 17(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bin, Yongjun Yu, Nianchun Jiang, Jianwu Wang, and Yuandan Ma. 2026. "Leaf–Litter–Soil C:N:P Coupling Indicates Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Across Subtropical Forest Types" Forests 17, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010068

APA StyleWang, B., Yu, Y., Jiang, N., Wang, J., & Ma, Y. (2026). Leaf–Litter–Soil C:N:P Coupling Indicates Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation Across Subtropical Forest Types. Forests, 17(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010068