1. Introduction

Hericium erinaceus (Bull.) Pers. is a fungus belonging to the phylum

Basidiomycota, family

Hericiaceae. It is distinguished by the formation of a characteristic white, fleshy fruiting body covered with basidiomata, i.e., delicate, thorn-like projections [

1]. This species is a saprotroph that develops on the wood of weakened or dead deciduous trees, including oaks, maples, and elms. At the same time,

H. erinaceus can develop and grow on living trees as a weak parasite [

2]. Throughout Europe,

H. erinaceus is very rarely found in forests. For this reason, this species has been placed on the red list of strictly protected species in countries such as Austria, Great Britain, Poland, and Slovakia [

3,

4]. In countries such as Japan and China,

H. erinaceus is common in forest environments. This has led to the edible fruiting bodies of

H. erinaceus being collected and used in traditional Asian cuisine for years due to their unique flavor. At the same time,

H. erinaceus has been recognized as an important health-promoting fungus with the ability to produce bioactive compounds that have beneficial effects on human health. For these reasons, the fruiting bodies are used to prepare various preparations in the form of dietary supplements and alternative medicines used in cases of gastrointestinal diseases (stomach ulcers), nervous system diseases (Parkinson’s disease), and autoimmune diseases (diabetes) [

5,

6,

7].

Recent research findings indicate that it is now possible to isolate compounds from the fruiting bodies and mycelium of

H. erinaceus, including polysaccharides, laccase, and hericenones, which possess high bioactive efficacy. Interestingly, determining the interactions between the bioactive molecules synthesized by the fungus phenols, terpenoids, and lactin is still a challenge. It should be emphasized that the full health-promoting properties of the terpenoids and phenols produced by Lion’s Mane Mushroom are not fully understood and are still being researched [

7]. However, it was found that biological compounds, i.e., fatty acids and polysaccharides produced by fungi, i.e.,

H. erinaceus and

Lentinula edodes (Berk.) (Pegler), have biocidal properties, including nematicidal and antibacterial properties [

8,

9]. Therefore, due to the ability of

H. erinaceus to synthesize valuable biological compounds with antimicrobial properties, it is desirable to use them in the protection of forest nurseries, which is a novelty [

10,

11,

12,

13]. This issue is very important and relevant, especially in relation to the direct threat to forest tree seedlings from the pathogenic fungi of

Fusarium spp. and the oomycete pathogens of

Phytophthora spp. Both pathogens can cause plant diseases in forest nurseries and in naturally regenerated seedlings [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, it is desirable to develop innovative plant protection products based on biological substances produced by fungi, including those of the genus

Hericium (Pers). The basis for undertaking work concerning the use of secondary metabolites produced by

H. erinaceus is the increasingly common use of biocidal compounds isolated from fungi in plant protection. A prime example is the use of secondary metabolites with strong fungicidal activity, which were isolated from the saprotrophic fungi

Clonostachys sp. Compounds isolated from

Clonostachys sp. have been used to protect vegetables and fruits against the fungal pathogen

Botrytis cinerea (Pers.), which contributes to their rapid rotting. The compounds produced by

Clonostachys sp. inhibit the germination of conidia and the activity of the

B. cinerea sclerotia and mycelium, contributing to its control. Also, compounds produced by

H. erinaceus, i.e., cerevisterol, may contribute to the inhibition of the growth of fungal pathogens, i.e.,

Glomerella cingulata (Stonem.) Spauld. & Schrenk [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

However, developing methods for culturing

H. erinaceus mycelium strains (vegetative mycelium occurring in the initial stages of growth) and extracting bioactive compounds from them, including those terpenoids, pyrones, flavonoids, and diterpenoids on an industrial scale, remains problematic. This makes it impossible to obtain sufficient quantities of bioactive substances used to develop new biocidal preparations [

3,

11,

12,

13,

14,

23].

The scientific examples cited above suggest the need to introduce a new strategy for cultivating

H. erinaceus mycelium to extract biologically active substances from it in laboratory conditions. To achieve this goal, it is beneficial to establish mycelial cultures of the fungus using various solidified substrates and a processed wood substrate in the form of oak sawdust prepared from individual wood layers (bark, sapwood, heartwood, and mixtures of individual wood layers [

24]. However, for fungal cultures to be characterized by high-quality mycelium, it is essential to select optimal factors that determine the initiation and stabilization of culture growth.

The first factor that plays a key role in the mycelial growth and survival of the fungus is the culture medium (culture medium). The main purpose of the medium is to meet the nutritional needs of the specific fungal species. Therefore, the composition of the nutritional medium must contain adequate amounts of carbohydrates (disaccharides), macronutrients, micronutrients, and water [

25,

26]. Therefore, selecting the appropriate medium composition primarily determines the development and appearance of the mycelium. The trophic mode and nutritional characteristics of the fungus, i.e., saprotroph or pathogen, and the specific purpose of establishing mycelial cultures, i.e., the production or the cultivation of new fungal varieties, also determine the use of particular types of solidified media. Among the vast number of known nutrient media used in laboratory cultures, the following solidified media are suitable: Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), Malt Extract Agar (MEA), and wort medium. PDA is commonly used in laboratory research for culturing mycelial cultures. Its basic composition includes potato extract, dextrose, and agar, a natural gelling agent obtained from marine algae [

27]. Another prominent synthetic medium used for fungal cultures is Malt Extract Agar (MEA). This medium has been used in laboratory research, among other things, for the sporulation process, i.e., the production of fungal spores. The distinguishing feature of MEA medium is the use of malt extract, maltose, peptone, and agar [

28]. The final medium used for establishing fungal cultures is wort agar medium. The main and basic component of wort medium is wort, i.e., an aqueous solution of substances including fermentable sugars (maltose 40.0%, maltotriose up to 20.0%, and glucose 15.0%), polyphenols, and minerals extracted from highly nutritious barley malt during the brewing process [

29,

30].

For the growth, intensification, and productivity of mycelial cultures to proceed properly, appropriate physical conditions must be established, including ambient temperature and the pH of the nutrient medium. These assumptions are crucial because different fungi have specific requirements regarding temperature and substrate acidity [

31,

32]. Establishing and maintaining the optimal temperature range directly influences the proper rate of mycelial growth, gas exchange, assimilation, and transport of nutrients, including simple sugars and biogenic elements, such as nitrogen, and their biosynthesis. Determining the appropriate range of cardinal temperatures for the tested species, i.e., minimum (initial), optimal (best fungal growth), and maximum (fungal growth inhibition), constitutes the basis for the possibility of establishing efficient and high-quality mycelial cultures [

33,

34].

At the same time, selecting the appropriate pH for the fungal species is crucial for, among other things, the growth potential of fungal cultures, changes in hyphal morphology through cell differentiation, and increased mycelium capacity to synthesize secondary metabolites. Most fungi prefer to grow in a medium with a pH ranging from acidic to neutral. However, selecting a nutrient medium within a specific pH range depends primarily on the fungal species’ ability to dynamically eliminate H+ ions, which are harmful to the growing mycelium, as well as the rate of nutrient assimilation [

25,

35,

36,

37].

In addition to establishing traditional mycelial cultures on artificial nutrient substrates prepared under sterile conditions, it can also be expanded to include culturing on a wood substrate in the form of sawdust, e.g., sessile oak (Quercus petraea Matt.) Liebl.

One of the main characteristics of trees belonging to the genus

Quercus is the evolution of a thick bark. The basic substances that form the bark’s structure include cellulose, pentosans and lignin. The chemical composition of bark also includes water-soluble substances, such as simple sugars, dyes, and water-insoluble substances, including sterols and fats. A distinctive feature of bark is its higher content of water-soluble minerals and lignin, and lower content of cellulose, compared to wood [

38]. Bark covers the top layer of wood, which is composed of organic substances, such as cellulose (approx. 40%), hemicellulose (approx. 25%) and lignin (approx. 20%) [

39]. The chemical compounds mentioned above are components of oak sapwood and heartwood. Sapwood consists of well-hydrated cells that form the outermost part of a woody trunk or branch. Due to its conductive function, the cells that make up sapwood are well hydrated. A characteristic feature of sapwood is its light color, resulting from the absence of chemical compound deposits that give it a darker color. The inner, woody part of an oak trunk is called sclerophyll, which strengthens the trunks and branches of trees. Heartwood is formed as a result of the natural aging process of sapwood cells, their death, and impregnation with substances such as gums. Oak heartwood is characterized by its dark color, which is due to the presence of chemical compounds within its cells, including phenolic compounds, flavonoids, tannins, oxycinnamic acids, and catechins. The most important function of phenolic compounds is to protect plant cells from infection and colonization by fungal pathogens. Polyphenols also have an ideal chemical structure for neutralizing oxygen radicals. This ability significantly reduces the risk of damage and death of the cells that form the wood structure. Oak species, in particular, are capable of synthesizing significant amounts of phenolic compounds in their heartwood and leaves to provide the trees with resistance to fungal attack [

40].

The individual oak wood components characterized above constitute an excellent nutrient substrate for many species of

Basidiomycota [

41]. Therefore, this study attempted to establish micellar cultures on oak wood. However, the use of solid oak wood fragments is difficult to implement in practice due to difficulties associated with the sterilization of the solid material, which often contains undesirable cultures of rot fungi, including

Daedalea quercina (L.) Pers.,

Fistulina hepatica (Schaeff.) With., and

Laetiporus sulphureus (Bull.) Murrill [

33,

42,

43,

44,

45]. For this reason, processed wood substrate in the form of sawdust was used in the conducted studies. The structure of sawdust facilitates its sterilization and the uptake of nutrients by fungi. As a result, it is possible to reliably assess the potential growth and intensification of the growth process of fungal cultures on the processed wood substrate [

46,

47].

The primary objective of the research presented in this paper was to determine the most favorable conditions for growing H. erinaceus mycelium under controlled conditions. The conducted research allowed for a detailed assessment of the type and acidity of the solidified substrate used and the influence of selected ambient temperatures. The research also included the selection of the most suitable wood substrate in the form of oak sawdust, made from sapwood, heartwood, bark, and a mixture of individual sawdust types.

The laboratory studies conducted provide a basis for improving the cultivation technique for H. erinaceus mycelium, which produces valuable biocidal compounds. This methodology may be used to develop more sophisticated techniques for producing biofungicides.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Research Material

This study used a fruiting body of the H. erinaceus from the fungal collection of the Department of Forest Ecosystem Protection at the University of Agriculture in Krakow (Poland). The fruiting body was grown on beech chips. H. erinaceus was stored in a growth chamber at a temperature of +/−20 °C. Humidity was approximately 50.0%, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, Mycomed-Medicinal Mushrooms Biosystems, Poland. The mushroom strain originates from Japan (Nagano Prefecture). The fruiting body was cultivated for 4 months.

Samples were collected from the cultivated fruiting body in the form of 10 mm mycelium discs. A total of 20 isolates were obtained and used for mycelium propagation. Each isolate was placed in a Petri dish with PDA+T medium (potato dextrose agar, Biocop, 200 mg/L tetracycline) prepared according to the recommendations of TZF Polfa, Krakow, Poland. Samples were incubated in a Heraeus incubator (model BK600, Burladingen, Germany) in the dark at 22 °C, with approximately 90.0% for 1 week. All isolates reached a diameter ranging from 20.0 to 35.0 mm. Ten isolates were then selected and subjected to genetic analysis using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method of the ITS region of rDNA, including ITS4 and ITS5 [

48,

49]. The extracted DNA sequences were processed using ChromasPro 1.6 software (Technelysium, Vienna, Australia) and verified against the NCBI GenBank database using the BLAST tool (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, BLAST + 2.17.0) to find the most similar gene sequences (

H. erinaceus: Taxonomy ID 91752).

2.2. Preparation of Substrates

We prepared 1.0 L of each of the three media. PDA (potato dextrose agar) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions, Biocorp (Poland). The wort medium consisted of 0.25 L of 9.0% beer wort, 0.75 L of distilled water, and 15.0 g of Lab-Lamco agar (Argenta Bestlab, Poznań, Poland). In the case of the preparation of maltose medium (MEA), 0.8 L of distilled water, 15 g of Lab-Lamco agar (Argenta Bestlab, Poznań, Poland), and 20 g of maltose dissolved in 0.2 L of warm distilled water were used.

Also prepared 2 L modified PDA medium without agar. The PDA medium was poured into 7 flasks of 0.29 L each. Then, to each flask with the medium, 0.030 mg/L to 0.086 mg/L of the selected acid or base solution was added to obtain the appropriate pH. The following chemicals were used to achieve the appropriate degree of acidity of the mediums: acids 1.8% HCl—4.0 pH (0.030 mg/L) and 4.5 pH (0.039 mg/L), 3.6% HCl—5 pH (0.048 mg/L), and bases: 0.5% NaOH—5.5 pH (0.057 mg/L), 1.0% NaOH—6.0 pH (0.066 mg/L), 2.4% NaOH—6.5 pH (0.075 mg/L), and 5.0% NaOH—7.0 pH (0.086 mg/L). The pH was measured using a portable electric pH meter, Mettler Toledo Seven2Go™ Pro DO meter S9, MT30207970-1KIT (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Next, 15.34 g/dm-3 of agar was added to the PDA media with pH 4.0, 4.5, and 5.0, respectively. For the PDA media with pH 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, and 7.0, 19.48 g/L of agar was added, respectively.

All prepared media were then sterilized in a Model MLS-830L-PE autoclave (PHC Europe BV, Breda, The Netherlands) for 30 min. The number of replicates (Petri dishes) for each of the three types of media (PDA, MEA and wort medium) was 12. The number of replicates (Petri dishes) for each of the seven types of media with a different pH (from 4.0 to 7.0) was 10.

2.3. Preparing the Wood Substrate

A fragment of a sessile oak trunk (1.0 m long) was used to prepare the processed food substrate in the form of sawdust. A fragment of an oak trunk came from forests located in the Spała Forest District (Mazovian-Podlasian Forest-Nature Region). The sampled trunk fragment was approximately 20–25 years old. Wood moisture was measured using a Trotec moisture meter (model MB12, Heinsberg, Germany). The moisture content of oak wood was 20.0%. In order to make sawdust, a single wooden disc was taken from the central part of the trunk. In order to make sawdust, a single wooden disc was taken from the central part of the trunk using a Husqvarna chainsaw (Model 365 X-Torq, Warsaw, Poland). The resulting oak disc had a total diameter of 185.0 mm. The radius of the wooden disc was measured using a measuring tape from the clearly visible core. The individual wood components had the following dimensions: heartwood—96.2 mm, sapwood—69.4 mm, and bark—19.4 mm. The disc was then cut in half using a Dedra 2000 circular saw (Dedra Exim, Pruszków, Poland) equipped with a Verto blade (ndiUnimet, Rzeszów, Poland) to facilitate the collection of bark and both types of wood. In the next step, sawdust was obtained from half of the wooden disc by filing away the bark and wood using a precision double-tooth saw from Neo Tools (GTX Group, Warsaw, Poland). The resulting sawdust was divided into three separate batches: bark sawdust, sapwood sawdust, and heartwood sawdust. Each type of sawdust was sieved through a 15 mm sieve. The weight of each type of sawdust was 4.0 g. Additionally, a sawdust mixture was prepared, consisting of sawdust from bark and the two types of wood. The sawdust mixture consisted of 0.42 g of bark sawdust, 1.5 g of sapwood sawdust, and 2.08 g of heartwood sawdust. Each type of sawdust was portioned into individual 0.4 g test samples, which were placed in individual aluminum foil sachets. All test samples were sterilized in a Model MLS-830L-PE autoclave (PHC Europe BV, Breda, The Netherlands) at 105 °C for 20 min.

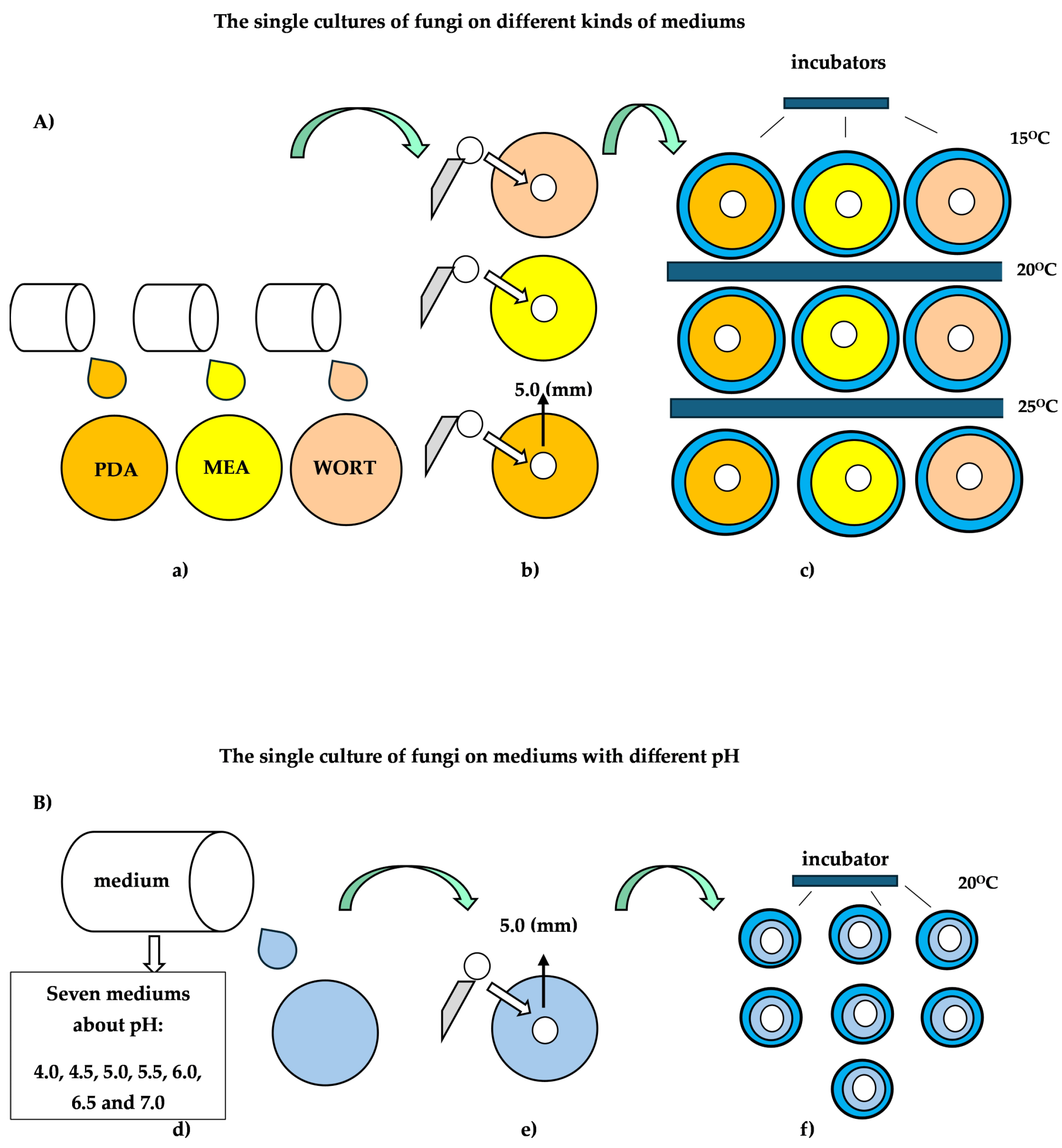

2.4. Mycelium Growth on Different Media and Ambient Temperatures

Individual 5.0 mm H. erinaceus isolates were excised from the actively growing margin of the colony and placed in the center of individual plates containing PDA, MEA, and wort medium. Each batch of inoculum-laden test media was grouped into three groups. Each of the three test groups contained fungal isolates placed on a different type of medium. The prepared groups with fungal isolates were placed in Heraeus incubators (Model BK600, Burladingen, Germany), with ambient temperatures set at 15 °C, 20 °C, and 25 °C, respectively.

Fungal cultures were placed in incubators for three weeks. The fungal growth of each strain was determined by analyzing the radial growth (two measurements perpendicular to each other per plate). Four replicate plates for each strain were incubated, and the radial growth, calculated in mm, was determined 5, 10, 15, and 20 d after inoculation.

A detailed diagram of the individual stages of the experiment using different substrates and temperatures is shown in

Figure 1A. The method of measuring the size of individual fungal cultures is shown in

Figure 2.

2.5. Mycelium Growth on Media with Different pH Values

The procedure for collecting fungal isolates and placing them on selected media with pH values of 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, and 7.0 was identical to that used to examine the effect of media type and temperature on the growth and development of

H. erinaceus cultures. All test samples were placed in a Heraeus incubator (Model BK600, Burladingen, Germany) maintained at 20 °C. The temperature of 20 °C was used to determine the effect of a specific medium on fungal culture growth without significantly affecting the ambient temperature. Growth characteristics were determined by analyzing radial growth (two culture size measurements per plate) of individual test samples. Fungal culture sizes were determined 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after inoculation. Size measurements of individual fungal samples are presented in mm. A detailed diagram of the individual experiments using media with different pH values is shown in

Figure 1B.

2.6. The Influence of Mycelium Development on Reducing the Mass of the Wood Substrate

A circular disk with a diameter of 30.0 mm was cut from individual Petri dishes containing an agar medium prepared from 15 g/L Lab-Lamco agar (Argenta Bestlab, Poznań, Poland) and 1 L of distilled water. The resulting gel disk was removed, leaving a circular hole. Sterile sawdust of each type was placed in each hole. Individual samples of sapwood sawdust, heartwood sawdust, and the resulting mixture of all sawdust types were moistened with 500 µL of distilled water each. All received batches of bark sawdust were moistened with 600 µL of distilled water each. Moisture content of individual test samples of sawdust was measured using a sterile moisture meter (Benetech Polska model GM620, Kalisz, Poland). The moisture content of the oak sawdust was +/−13.0%. The number of replicates of Petri dishes for each of the four types of prepared sawdust was 10.

Then, a single H. erinaceus isolate (a 5.0 mm diameter plug) was placed in individual dishes containing sawdust made from bark, sapwood, heartwood, and a mixture of sawdust made from individual kinds of wood parts. The fungal isolates were gently pressed onto the wood substrate. All test samples were placed in a Heraeus incubator (Model BK600, Burladingen, Germany) at ±20 °C. After the study was completed, all sawdust types, along with the fungal cultures growing on them, were transferred to aluminum bags and placed in an autoclave model MLS-830L-PE (PHC Europe BV, Breda, The Netherlands). All sawdust samples were dried to remove mycelium. The drying process was carried out at 105 °C for 20 min.

After thoroughly drying the test samples, the actual mass of the four types of sawdust was obtained. The resulting sawdust mass was reduced due to the growth of the fungal cultures on the wood substrate. All test sawdust samples were then weighed on a digital analytical balance (Explorer Analytical OHAUS Europe, Nänikon, Switzerland). The mass loss of the wood substrate was determined as the difference in the sawdust mass at the beginning of the test and the resulting sawdust mass at the end of the test. The fungal cultures grew on the sawdust for 30 days. A detailed flowchart of the individual stages of the experiment using a substrate made of oak sawdust is presented in

Figure 3.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

To verify the assumption that the type of medium, including PDA, MEA, and wort medium, and the selection of temperature ranging from 15 °C to 25 °C, determined the growth and expansion rate of H. erinaceus cultures, a one-way ANOVA test was performed with a significance level of p < 0.05. The one-way ANOVA test was performed separately for selected media types and selected temperatures.

The validity of the previous statistical analysis was verified by analyzing the resulting 95.0% confidence intervals for the obtained mean values of the fungal cultures. The analyses were presented separately for selected media types and temperatures.

A statistical study of the effect of medium pH and the duration of fungal culture incubation on their growth rate was also conducted, as well as an analysis of the joint effect of specific medium pH and the growth rate of fungal isolates using multivariate ANOVA.

The significance of the effect of specific substrate pH and incubation time on the growth of cultures was examined using a one-way ANOVA. The mean growth of mycelium cultures was also analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. The obtained results were verified by considering the obtained confidence intervals at the 0.95% level.

The significance of the effect of fungal cultures on the mass loss of the wood substrate was then analyzed using the Student’s t-test. A significance level of p = 0.05 was adopted.

All statistical analyses were performed using DELL STATISTICA version 13.1 (Dell Inc., Grove St., Newton, MA, USA).

4. Discussion

Fungicides, as plant protection products, are widely used for effective control of phytopathogens. Unfortunately, many currently produced fungicides contain synthetic substances, such as triazoles and carboxamides, which, when used in excess, can have a detrimental impact on the environment and human health. Therefore, the development of biodegradable fungicides is desirable [

50,

51]. This fact has led to many scientific disciplines and specialties, such as forestry, agriculture, and biotechnology, paying special attention to the possibility of using active substances synthesized by fungi to develop innovative biopesticides [

52]. In order to isolate and obtain fungicidal substances, it is advisable to use mycelium

H. erinaceus, taken from the fruiting bodies of the species grown under commercial conditions. Current methods of cultivating fruit bodies involve growing them on a nutrient substrate consisting of a mixture of sawdust from deciduous trees, such as beech, or shredded corn or rice straw. Commercial cultivation requires a humidity level of about 65.0% [

53,

54,

55,

56]. This prevents drying out of both the nutrient substrate and the growing hyphae. However, obtaining a fruiting body is a lengthy process, taking several months, which reduces the likelihood of isolating fungicidal substances from the fruit body. Therefore, the focus has been on developing optimized laboratory techniques for culturing mycelium

H. erinaceus.

To isolate bioactive compounds, including secondary metabolites, special attention should be paid to ensuring optimized culture conditions, which directly impact the quantity and quality of the cultivated mycelium. The experiments described in this article enable the modernization of current fungi cultivation techniques in laboratory conditions, which in practice translates into increased mycelium production and the isolation of valuable bioactive substances from it. The conducted research and analysis included multifactorial culture conditions, including various ambient temperature ranges, solidified media pH, and nutrient substrate types (nutrient media and wood substrate), on the achievement of high-quality H. erinaceus cultures within a short incubation period.

Experiments examining the effects of temperature and substrate type demonstrated a significant impact of their selection and use in cultivating mycelium characterized by large surface culture sizes and a compact hyphal structure. Studies using

H. erinaceus cultures demonstrated a significant correlation between the effects of substrate type and temperature selection (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). It should be emphasized that determining the fungus’s thermal preferences is crucial for achieving the required culture size. The preferred growth conditions for

H. erinaceus at various temperatures observed in the conducted experiments are likely genetically determined and directly related to the location and climatic zone in which the species occurs in its natural environment. This assumption is confirmed by the research on various strains of the health-promoting fungus species

Ganoderma chalceum (Cooke) Steyaert. The studies showed that two different strains of

G. chalceum, collected from different ecosystems, have different thermal preferences necessary for their intensification of the growth process. The analyses carried out showed that the

G. chalceum strain collected from the areas of volcanic hills poor in vegetation had higher thermal preferences (ca. 30 °C) compared to the strain of the same species collected from the habitats of evergreen equatorial forest (ca. 25 °C) [

57,

58].

However, it should be emphasized that determining the optimal temperature range can be directly correlated with the selection of an appropriate nutrient substrate. The effect of these two factors results in the rapid growth of mycelium cultures in a short period of time. This assumption is confirmed by the results of studies using cultures of the fungi

Grifola gargal Singer and

Grifola sordulenta (Mont.) Singer. Tests conducted by Postemsky and Curvetto (2014) showed that the selection of the optimal fungal incubation temperature depended on the type of medium used to inoculate the mycelium [

59]. The relationships presented above were also observed in experiments conducted by Zervakis et al. (2001) [

25], in which it was observed that the growth rate of fungal cultures, i.e.,

Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler and

Pleurotus pulmonarius (Fr.) Quel. in the range of preferred temperatures (from 15 °C to 40 °C) and substrates (PDA medium and cellulose substrate) depend on the selection of the appropriate food substrate used [

25].

Selecting the appropriate pH also plays a crucial role in selecting the most favorable nutrient medium for the growth of a specific fungal species. The results of studies using

H. erinaceus cultures demonstrated the significant impact of optimal pH on the growth rate of the tested fungus during the initial incubation period of each culture. The experiment showed that

H. erinaceus cultures achieved the fastest growth rate at an acidic pH. Interestingly, however, later in the incubation period for all the test samples, the growth sizes of the individual cultures became equal regardless of the medium pH (

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). These results are likely due to the broad adaptability of the fungal cultures to growth in a variety of media of the specific strain studied. This assumption is supported by studies of strains of

Lentinus squarrosulus Mont. growing on media with a range of pH values from 5.0 to 8.0. Observations revealed that two strains of this fungus (labelled as 1 and 2) had different preferences for appropriate nectar acidity. The experiment showed that

L. squarrosulus strain 1 grew best in a medium with an acidity ranging from 5.0 to 7.0 pH, in contrast to

L. squarrosulus strain 2, whose optimal culture growth rate was observed in a narrower acidity range of 5.0 to 5.5 pH [

60]. The assumptions presented above demonstrate that the type of medium, temperature, and pH have a significant impact on maximizing the growth rate of fungal cultures. Therefore, it is desirable to continue further research aimed at optimizing the growth processes of fungal cultures. This is crucial because the selection of optimized culture conditions allows fungal cultures to achieve maximum metabolic expression. Consequently, it is possible to increase the production of a selected biochemical compound, which can be used in the production of modern drugs [

61,

62].

However, for controlled cultivation, it is also possible to use mechanically processed wood substrate in the form of various types of sawdust. The research results presented in this paper demonstrated a significant effect of growing

H. erinaceus cultures on the greatest reduction in sapwood sawdust mass. However, in the case of the other types of sawdust used in the experiment, i.e., those made from bark, heartwood, and a mixture of both types of wood and bark, no significantly lower reduction in wood mass was observed by the fungal cultures (

Table 8,

Figure 9). The reason for the large reduction in sapwood sawdust mass is the lower saturation of sapwood cells with compounds, such as phenols, which are harmful to fungal organisms [

63]. However, the cells of heartwood and bark contain large amounts of compounds from the group of hydrolyzed tannins, including castalagin, vescalagin, and salicarinins A–C. The hydrolysis of the aforementioned tannins leads directly to the formation of gallic acid and ellagic acid. These compounds are characterized by high toxicity towards fungal pathogens. The mechanism of action of gallic acid and ellagic acid involves inhibiting the germination of spores and mycelium growth, as well as damaging the cell membrane structure of the fungal pathogen [

64]. At the same time, oak bark contains large amounts of tannins, i.e., ellagitannins and gallotannins, which can slow down enzymatic reactions carried out by fungi [

65,

66,

67]. For this reason, the above-mentioned plant compounds, which primarily act as biocidal agents for fungal organisms, also reduce the colonization rate of heartwood sawdust. Furthermore, the presence of tannins in oak heartwood is directly related to the durability of the wood to damage. This fact suggests that mechanically processed wood substrate is saturated with sufficient amounts of tannins to hinder the growth of fungal hyphae into the wood. As a result, the ability to absorb nutrients from the wood substrate is significantly hindered, and the size of mycelium cultures is smaller compared to cultures growing in sapwood sawdust [

68,

69].

The presented research results demonstrate that they can be used to determine the best solidified substrate and thermal conditions that favorably influence the escalation of fungal cultures, as well as to determine the colonization potential of individual fractions of oak sawdust as a food substrate. Based on the experiments, optimal culture conditions for the expansion of H. erinaceus cultures were characterized, which synthesize valuable chemical compounds that can become the basis for the elaboration of both environmentally friendly plant protection products and innovative pharmaceuticals.

5. Conclusions

The present study has led to the development of a modernized H. erinaceus culture technique, which will be used in the future to increase the production rate of high-quality mycelium, which has the ability to produce natural biocidal substances.

Fungicidal substances extracted from the mycelium, including polyphenols and flavonoids, will be used to develop environmentally friendly plant protection products.

The results indicate that the selection of an appropriate nutrient substrate and temperature significantly influenced the intensification of the growth of mycelium. The selection of PDA substrate and the highest temperature proved to be the most effective combination in controlled conditions, promoting the growth of cultures. This translates into increased efficiency, isolation, and production of valuable fungicidal compounds from the cultivated mycelium of the species.

It was also found that the selection of nutrient media characterized by a very acidic pH significantly influenced the intensification of the growth process of mycelium with desirable morphological characteristics (a well-grown, compact mycelium structure capable of synthesizing valuable secondary metabolites).

The results of the conducted research constitute the basis for the development of innovative mixtures of laboratory substrates consisting of processed wood substrate, i.e., sawdust made from sapwood of deciduous trees.

The use of substrate in the form of sapwood sawdust is an excellent source of nutrients, which is rapidly utilized by H. erinaceus, guaranteeing the production of large amounts of high-quality mycelium, which will be used to isolate fungicidal substances, secondary metabolites, and health-promoting substances.

The presented research has significant practical value in breeding of H. erinaceus. It was observed that the presented breeding methods allowed for a significant reduction in the time required to obtain mycelium (from several months to several days), in contrast to the common method of cultivating fruiting bodies on a substrate in the form of mixtures of wood chips and cultivated plants.

The conducted research also provides a scientific basis for further research into the properties of yet unknown health-promoting substances produced by H. erinaceus mycelium, which are used to treat and prevent lifestyle diseases such as cancer and diabetes.