Abstract

The Common European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) is one of the main species constituting the field protection forest belts in Northeastern Bulgaria. Studies conducted in shelterbelts in Dobrich and Balchik in July 2020 and in Tutrakan and Dulovo in June–July 2022 revealed severe dieback of ash. The observed symptoms included density thinning of the crowns, dieback of branches, presence of sunken necrotic cankers, and light green to yellow foliage and premature defoliation. Parts of the shelterbelts were completely destroyed with 100% tree mortality. To determine whether the invasive Hymenoscyphus fraxineus or other pathogens are present in the ash field protective forest belts in Northeastern Bulgaria, fungal isolation was undertaken. Samples were collected from four locations: Dobrich and Balchik in June 2020, and Tutrakan and Dulovo in June–July 2022. The morphology, temperature–growth rate relationships, and pathogenicity of the two pathogenic fungal species isolated in this study—Diplodia fraxini and Diplodia seriata—were examined. Morphological and physiological studies confirm the molecular identification of the obtained plant pathogens. The Diplodia fraxini isolates (Dobrich 3, Tutrakan 2, and Dulovo 4) showed mycelial growth between 5 °C and 35 °C, with minimal growth at 5 °C (0.20–0.27 mm/day) and an optimum growth rate of 3.9–4.5 mm/day at 20–25 °C. Growth declined sharply above 30 °C, ceasing entirely at 35 °C. In contrast, D. seriata (Dulovo 5) exhibited higher growth rates, showing limited growth above 5 °C (~1 mm/day), and maximum growth of approximately 8 mm/day at 25 °C. Growth in D. seriata remained moderate up to 35 °C and ceased near 40 °C, indicating a broader temperature tolerance and higher upper thermal limit than D. fraxini. The results from the pathogenicity tests show that D. fraxini can cause necrosis on ash—both on leaves and twigs—and is likely involved in the investigated ash decline cases. Further studies of the spread and epidemiology of D. fraxini are needed in order to establish its occurrence on the territory of Bulgaria.

1. Introduction

The Common (European) ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) is an important tree species, naturally distributed across the European temperate zone [1]. The species is very flexible and can be found over a wide range of growing conditions [2]. Ash thrives in the zone between the softwood and hardwood communities in floodplain forests, and has been dominating it until very recently, before the appearance of ash dieback disease. Two decades after the first observation of ash dieback, the disease was predicted to alter the forest structure and species composition of vital forest communities on moist soils in the future [3].

Bulgaria is located in the lower part of the distribution range of the common ash [1], and F. excelsior can be found in the riparian floodplain forests of the lowlands and in the mountainous areas of the country. Both habitats are important sources of biological and genetic diversity for rare and endangered species [4]. Additionally, F. excelsior is one of the main species constituting the field protection forest belts in Dobrudja. These linear plantations were established in the mid-20th century to mitigate the negative impact of the year-round strong winds on the agricultural crops. An in-depth examination of the health status of the field protective forest belts in Bulgaria was carried out in 2022 [5]. Results from this monitoring show that since 2014, the area of the protective forest belts in poor condition has increased 2.6 times. Both Fraxinus excelsior (66% of all trees in the belt stands) and Fraxinus americana L. (10%) were in the poorest condition. A process of crown dieback, premature defoliation, and dieback of whole trees was observed in the ash belts. In some individual plantations, dieback has affected up to 80% of tree crowns, regardless of their age and origin. The dieback was attributed to insect pests and fungal pathogens [5,6]. Similarly to other multifunctional protective forests in Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe, the ash shelterbelts in Northeastern Bulgaria play a key ecological role in mitigating wind erosion, regulating microclimate, and maintaining soil fertility in intensively cultivated areas. Their degradation may therefore have cascading effects on local environmental stability [7].

The European ash dieback phenomenon became prominent in the early 1990s, when intensive dieback of ash was observed to spread over Poland. The causative agent described was Chalara fraxinea T. Kowalski sp. nov. [8]. A teleomorph of the pathogen was later discovered [9], and following the abandonment of the dual naming system, the nomenclatural correct name for the fungus causing ash dieback was determined to be Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (T. Kowalski) Baral, Queloz, Hosoya [10]. In the Balkans, H. fraxineus was found to be responsible for severe ash dieback, both on Fraxinus excelsior and F. angustifolia Vahl in Romania [11]. The symptoms of ash dieback disease were observed in 2015 in Serbia, and the presence of the H. fraxineus pathogen has been reported for two years [12].

The aim of our study was to determine whether the invasive H. fraxineus or other pathogens are present in the ash field protective forest belts in Northeastern Bulgaria. Isolations of fungi were undertaken from diseased ash twigs. The morphology, temperature–growth rate relationships, and pathogenicity of the two pathogenic fungal species obtained in this study—Diplodia fraxini and Diplodia seriata were examined. In this paper we present the results from our investigation and discuss the role of the identified fungal pathogens in the instances of European ash decline in Bulgaria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Sample Collection

In June 2020 we investigated declining Fraxinus excelsior linear plantations, aged between 35 and 70 years, located on the territory of State Hunting Enterprises Balchik and State Forest Enterprises Dobrich, Bulgaria. During the survey we collected samples consisting of branches with cankers. We carefully investigated the leaf debris of the previous year for the presence of ash petioles with pseudosclerotia of H. fraxineus. For the isolation of oomycete species, rhizosphere soil samples consisting of soil and fine roots taken from the four sides of the tree trunks were collected. All samples were transported to the laboratory in a cool box, and stored at 4 °C for several hours.

In June–July 2022, we analyzed Fraxinus excelsior twigs exhibiting cankers, collected from forest protection belts in Tutrakan and a wood production plantation in Dulovo. All of the samples were from ash plantations affected by severe dieback.

At each site, four trees with a relatively uniform height were examined (undergrowth or seedlings were excluded). From each selected tree, five branches approximately 35 cm long were collected for analysis, including both current-year (terminal) and previous-year branches bearing visible cankers. Tree age and branch height were not recorded, as the trees were of similar size and height across the stands.

Detailed information of the locations and samples collected in 2020 and 2022 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Bulgaria with sample sites of the ash plantations investigated showing dieback (red dots).

2.2. Isolation of Fungi from Ash Twigs and Baiting of Oomycetes from Rhizosphere Soil

The samples collected in Dobrich and Balchik were analyzed in 2020, and those collected in Dulovo and Tutrakan in 2022. Tissues with necrotic lesions were cut into 3–4 cm segments and thoroughly rinsed under running water to remove surface debris and spores, then dried with sterile filter paper. Under laminar flow, samples were disinfected by immersion in 70% ethanol for 1 min, followed by treatment with a 1:1 solution of Ace Bleach Classic (containing 1%–5% sodium hypochlorite, 1%–3% sodium carbonate, and 0%–1% sodium hydroxide) and sterile distilled water for 30 s. The segments were then rinsed twice in sterile distilled water for 2 min and dried with sterile filter paper. Small plant tissue parts from the margin of the necrotic lesions were placed on BD DIFCO™ Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and on PDA amended with 10 mg/L rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany) and 200 mg/L Ampicillin sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH) in 9 cm Petri dishes. They were incubated in a thermostatic chamber at 20 °C in the dark. Systematically, the appearing fungal colonies were re-cultured on new agar plates without antibiotics. For isolation of oomycete species present in soil, a soil baiting technique was used [13]. Portions of 300–400 cm3 from each soil sample were placed on the bottom of a plastic box to form a layer with height about 4–5 cm. Sterile distilled water was added to the boxes, until reaching 2–3 cm above the soil. Young ash leaflets were placed on the water surface in order to attract oomycete zoospores. Oomycetes in the soil are indicated by the formation of distinct small necrotic spots on the ash leaflets.

2.3. DNA Isolation, Amplification, Sequencing, and Analysis

Single cultures of all isolates selected for molecular identification were obtained by the hyphal tip technique [14] and transferred on half strength PDA. After 5–6 days the aerial mycelium of each isolate was scraped with a sterile scalpel, frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground for subsequent DNA isolation. Total DNA was isolated by using DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions. Next, DNA amplification of the ITS region with Primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) [15] was performed by using Illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR kit. The following thermal program was applied: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 120 s and 35 cycles of the following: denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 50 s, with final elongation at 72 °C for 30 s and cooling at 4 °C for ∞. The amplified target DNA was purified with PCR/DNA clean up Purification kit (EURx Poland, Banino, Poland) and sent for Sanger sequencing at the Eurofins Genomics, Germany (https://eurofinsgenomics.eu, accessed on 1 November 2025). The obtained sequences were quality-checked, and low-quality reads were removed prior to submission. The processed sequences were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database. Sequence similarity searches with the deposited sequences in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Bank database for the identification of the species were conducted using the basic length alignment search tool (BLAST) with an Expect threshold of 0.05. Sequences of the isolates Dobrich 3, Dulovo 4, and Tutrakan 2 were compared with reference sequences from ex-type cultures of Diplodia fraxini [16] by pairwise sequence alignment using the NCBI BLAST ’Align two or more sequences’ tool. Additionally, all sequences were benchmarked to the UNITE fungal ITS database (version 10.0; Last updated: 17 June 2025) [17] using BLASTN 2.15.0+ with default parameters and an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5.

2.4. Morphology, Growth Rates, and Pathogenicity of Diplodia fraxini and D. serata Isolates

2.4.1. Morphology

All isolates were maintained on PDA. For the formation and observation of conidiomata and conidiospores, isolates were grown on Duchefa Plant agar (https://www.duchefa-biochemie.com, accessed on 1 November 2025), amended with autoclaved ash plant tissue. Three autoclaved F. excelsior leaflets per Petri dish were semi-submerged on the surface of the previously poured plant agar media. The Diplodia isolates Dobrich 3, Dulovo 4, Tutrakan 2, and Dulovo 5 were grown on prepared media in daylight and at room temperature until the formation of the pycnidia. After 10 days, parts of the leaflets (1 cm2) covered with pycnidia were cut out from the agar and transferred to a moisture camera for 48 h for the release of the conidiospores. For the morphology studies, a stereo microscope Nikon SMZ745T and a compound microscope ZEISS Axio Imager A2 with a digital camera (AxioCamERs 5S) and a biometric software (Labscope Version 3.3.) were used. The lengths and the widths of 25 conidiospores per isolate chosen at random were determined at ×400 magnification.

2.4.2. Growth Rates and Cardinal Temperatures

Growth rates and cardinal temperatures were determined by incubation of the isolates at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 °C (±0.5 °C). For each temperature, sets of three replicate PDA plates (90 mm) per isolate were prepared by placing an agar piece (approx. 4 × 4 × 3 mm) with mycelium in the center of a Petri dish. The Petri dishes were incubated overnight for initiation of the mycelial growth on the PDA. Two perpendicular lines, intersecting the forming mycelial colony, were drawn on each Petri dish and the periphery of the colony was marked, indicating the starting point of the measurements. Thereby, prepared cultures were incubated in the growing chamber at the corresponding temperatures in the dark. After 3–9 days of incubation, the linear mycelial growth along the four radial lines of each Petri was measured. The average radial growth rate per day (mm/day) was calculated based on the obtained data [18].

2.4.3. Pathogenicity Tests

An assessment of the pathogenicity of the D. fraxini isolates (Dobrich 3, Dulovo 4, and Tutrakan 2) and the D. seriata isolate Dulovo 5 was carried out using detached ash leaves and cuttings in two experimental trials. Well-developed leaves of F. excelsior were collected at the beginning of the tree’s vegetation period. Ten leaflets per isolate were inoculated by placing agar plugs (approx. 4 × 4 × 3 mm) from fresh fungal colony grown on PDA on the leaflets, facing their adaxial sides. The leaf surface under the agar plugs was slightly punctured with a sterile needle. For the control, a clean PDA plug was used. A small droplet of sterile water was added with a pipette between each leaflet and agar plug to ensure contact between the plant and the mycelium. Inoculated leaves were kept in sterilized 120 mm glass Petri dishes on wet filter paper in daylight and at room temperature for ten days. Additionally, around 10 cm long cuttings from green twigs of F. excelsior were collected in the middle of the vegetation period. Five cuttings were inoculated with agar plugs of each one of the four isolates. A piece of bark, about 1 cm, of each cutting was removed and an agar plug taken from a well-developed culture of each isolate was placed on it. Inoculated cuttings were kept in Petri dishes on wet filter paper and incubated in daylight and at room temperature for 10 days. To prove the pathogenicity of the D. fraxini isolates, according to Koch’s postulates, their re-isolation from the necrotic lesions formed on the inoculated leaves and cuttings was performed as described in Section 2.2. The obtained fungal isolates were identified based on colony morphology.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The measurements of lengths and the widths of 25 conidiospores were compiled in Excel. Descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation (SD), were calculated using the AVERAGE and STDEV functions, respectively. The daily radial growth (mm) of fungal colonies was recorded over the incubation period, and the radial growth rate (mm/day) was calculated by dividing the total radial growth by the number of incubation days. The mean and standard error of the mean (SE) were calculated to represent the precision of mean estimates in replicate growth rate experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Field Studies

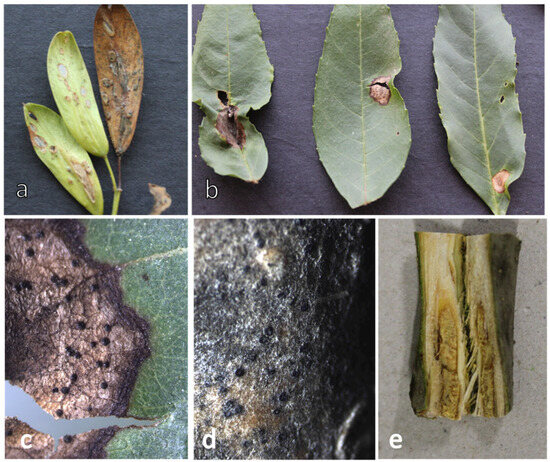

The field study conducted in shelterbelts in Dobrich and Balchik in July 2020 revealed severe dieback of ash. The observed symptoms included crown density thinning, dieback of branches, the presence of sunken necrotic cankers, light green-to-yellow foliage, and premature defoliation (Figure 2a–d). Parts of the shelterbelts in Dobrich and Balchik were completely destroyed with 100% tree mortality (Figure 2b). On the leaves and winged fruits of the lower branches, light-brown necrotic spots with dark-brown periphery were noticeable. Leaf petioles exhibiting characteristic black pseudosclerotia of H. fraxineus were not observed during the litter investigation of the stands. In 2022, similar symptoms were observed in the shelterbelts in Tutrakan, as well as in a forest production plantation in Dulovo (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Symptoms of decline observed in ash shelterbelts: (a) distant view of declining linear plantations in Dobrich, (b) dead ash trees in Balchik shelterbelts, (c) abnormally small leaves and thin crowns in Balchik, (d) brown spots on the foliage and winged seeds in Balchik, and (e) severe crown dieback with clumps of foliage at the base of branches in Dulovo.

3.2. Fungal Isolates Obtained from Ash Twigs

The examination of the samples from Tutrakan showed that the necrotic spots on the leaves and bark were covered with numerous globose pycnidia (Figure 3a–d). An abundance of characteristic septate conidia of Diplodia spp. was observed in the affected plant tissues under the microscope. Cross sections of twigs with cankers revealed oval-shaped wood necrosis (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Symptoms of infection observed on different plant parts sampled from Tutrakan: (a) necrotic lesions on winged seeds, (b) necrotic lesions on leaves, (c) pycnidia on leaves, (d) pycnidia on bark, and (e) cross section of a diseased ash twig showing necrosis.

Twenty-two fungal isolates were obtained from the samples collected in 2020, and ten from the samples collected in 2022. Based on morphology, the isolates were assigned to nine morphotypes. One representative from each group was processed for molecular identification. No oomycetes were isolated during baiting of rhizosphere soil samples.

3.3. Molecular Identification

The taxonomic identification of the fungal isolates obtained in this study was based on highly similar ITS sequences in NCBI with 99.2 to 100% identity, as well as on exact matches (100% identity, zero mismatches, E-value 0.0) to multiple reference sequences in the UNITE database.

The species identification and the assigned GenBank accession numbers for the deposited nucleotide sequences are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and molecular identification of fungal isolates obtained from symptomatic ash samples collected in the current study. The table presents isolate names, collection dates, sampling locations, and species identification results based on highly similar ITS sequences in NCBI GenBank and UNITE database matches. Letters following isolate names (e.g., a, b) indicate separate isolates obtained from the same sample.

The blast search in NCBI GenBank database revealed that the sequences of the isolates Dobrich 3, Tutrakan 2, and Dulovo 4 exhibited the highest homology (100% identity) with Diplodia fraxini and Diplodia mutila. The matching D. fraxini sequences were more recently deposited, compared to those of D. mutila, which dated prior to the end of 2017. Pairwise alignment with sequences of ex-type isolates published by ref. [16] demonstrated 98.80% sequence identity with 100% query coverage (isolate Tutrakan 2) and 100% sequence identity with 96% query cover (isolates Dobrich 3 and Dulovo 4) with the referent D. fraxini type isolate CBS 136010 (KF307700). Pairwise alignment against D. mutila CBS 136014 (KJ361837) showed 99.04% sequence identity with 90% query coverage for isolate Dobrich 3. Isolates Tutrakan 2 and Dulovo 4 showed 98.16% and 98.88% sequence identity, respectively, both with 93% query coverage. The sequence of isolate Dulovo 5 had the highest similarity with D. seriata isolates Bot-2018-DS51 (MW560096.1), Bot-2018-DS113 (MW560100.1), and several others, all showing ≥99.8% sequence identity. Based on these results, isolate Dulovo 5 was identified as Diplodia seriata.

3.4. Characterization of Diplodia fraxini and D. seriata Isolates

3.4.1. Morphology

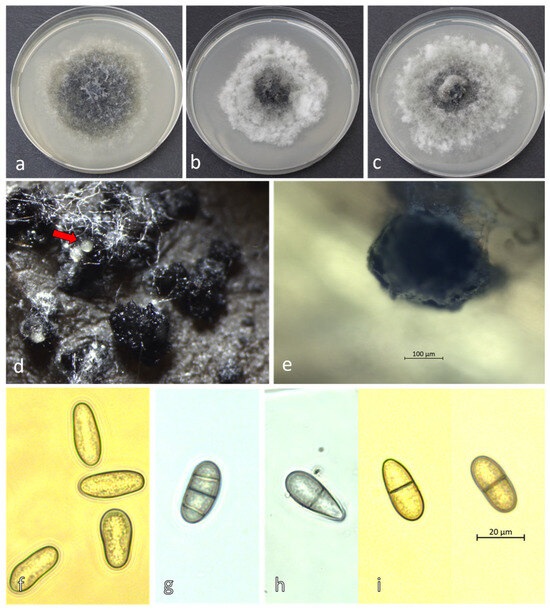

Diplodia fraxini

The D. fraxini isolates (Dobrich 3, Dulovo 4, and Tutrakan 2) developed fluffy white colonies that darkened to pale gray or black on PDA (Figure 4a–c). After 10–15 days the pycnidia of the isolates formed on the surface of the ash leaves agar media (Figure 4d,e). Pycnidia formed within 10–15 days on ash leaf agar, releasing conidia that were initially hyaline and aseptate, later becoming brown and septate (Figure 4d–i). Their average size was 27.01 μm ± 1.68 × 11.6 μm ± 1.28 for Dobrich 3, 25.28 μm ± 1.88 × 12.14 μm ± 1.16 for Dulovo 4, and 24.50 μm ± 2.65 × 11.12 μm ± 1.62 for Tutrakan 2.

Figure 4.

Morphology of Diplodia fraxini: colonies on PDA at 25°C: (a) Dobrich 3, (b) Tutrakan 2, (c) Dulovo 4; (d) in vitro pycnidia with oozing conidiospores (red arrow); (e) a single pycnidium of isolate Dulovo 4 in culture at 400× magnification; (f) immature, aseptate hyaline conidiospores of Dobrich 3; (g–i) mature, septate pigmented conidiospores on ash leaf in culture after 2 days in a moist chamber: (g) Dulovo 4, (h) Dobrich 3, and (i) Tutrakan 2.

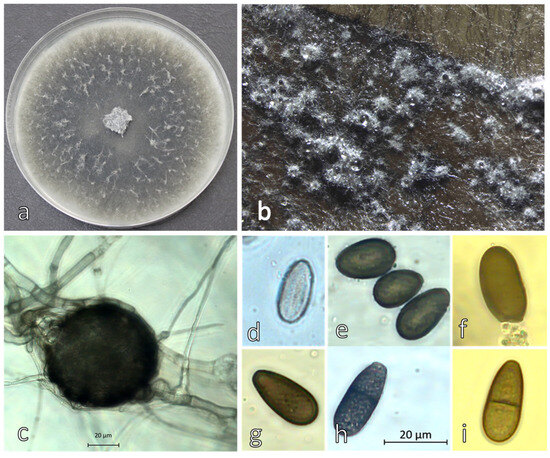

Diplodia seriata

The mycelium of D. seriata Dulovo 5 isolate grew faster and formed darker colonies with reduced aerial mycelium compared to D. fraxini isolates (Figure 5a). After 10–15 days the pycnidia were formed on the surface of the ash leaves agar media (Figure 5b). They were smaller in size (Figure 5b,c) and more abundant compared to D. fraxini (Figure 4a–c). The conidia were dark brown, more often aseptate and less abundant (Figure 5d) compared to D. fraxini, with average size 21.45 μm ± 3.25 × 11.11 μm ± 1.34.

Figure 5.

Morphology of Diplodia seriata Dulovo 5 (a) colony on PDA after 6 days at 25 °C, (b,c) pycnidia on ash leaf in vitro; (d) immature aseptate hyaline conidiospore and (e–i) mature septate pigmentated conidiospores.

After incubation for 48 h in a moist chamber at room temperature and daylight, the conidiospores (Figure 4d–i) were released from pycnidia.

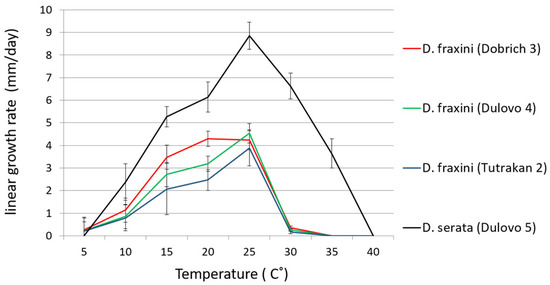

3.4.2. Growth Rate and Temperature Response

The Diplodia fraxini isolates (Dobrich 3, Tutrakan 2, and Dulovo 4) exhibited mycelial growth over a temperature range extending from below 5 °C to 35 °C.

Growth was minimal at 5 °C (between 0.20 and 0.27 mm/day−1) increased steadily with temperature, and reached its optimum between 20 °C and 25 °C (mean growth rate 3.9 to 4.5 mm/day−1). Above 30 °C, growth declined markedly, and no growth was observed at 35 °C.

In contrast, D. seriata (Dulovo 5) demonstrated a higher growth rate, with limited growth above 5 °C (~1 mm day−1) and maximum growth at 25 °C (around 8 mm/day−1). Growth remained moderate up to 35 °C and ceased near 40 °C. Overall, D. seriata displayed a broader temperature range and higher upper thermal limit compared with D. fraxini (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Growth rates of D. fraxini isolates Dobrich 3, Tutrakan 2, Dulovo 4, and D. serata Dulovo 5 at various temperatures (°C). Bars represent standard errors.

3.4.3. Assessment of Phytopathogenicity

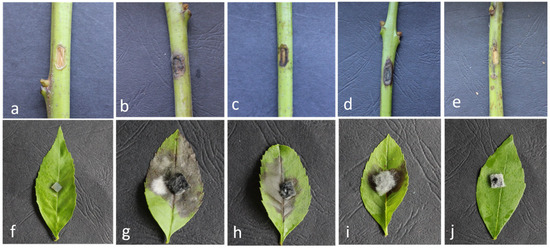

After 11 days, the leaflets inoculated with D. fraxini developed necrotic spots covered with aerial mycelium of the fungal pathogen (Figure 7g–i). On the cuttings inoculated with D fraxini, after 10 days, the plant tissue around the wounds became black and necrotic (Figure 7b–d). On the leaflets (Figure 7e) and cuttings (Figure 7j) inoculated with D. seriata, invasion of the fungus in the plant tissue was not observed, which was the same for the controls (Figure 7a,f).

Figure 7.

Artificially inoculated F. excelsior leaflets and cuttings with agar plugs of D. fraxini and D. seriata isolates: (a,f) controls, (b,g) Dobrich 3, (c,h) Tutrakan 2, (d,i) Dulovo 4, and (e,j) Dulovo 5 after 10 days.

The isolates obtained from the re-isolations from the necrotic lesions on the leaves and cuttings were identified as D. fraxini based on colony morphology.

4. Discussion

Since the early and mid-1990s, when the European ash dieback phenomenon became prominent, considerable efforts have been made for the clarification of its etiology and understanding of the disease [2,19,20,21,22,23]. One of the first studies of ash dieback in Poland carried out in 2002 indicated the involvement of Diplodia mutila (Fr.) Fr 1849. The pathogen’s role in the formation of stem bark necrosis on F. excelsior was demonstrated through stem inoculations [24]. After 2006 ash dieback was associated with the invasive pathogen H. fraxineus [8,11,12,19].

However, Diplodia mutila was among the frequently isolated species, together with H. fraxineus in a F. excelsior dieback study in Poland [25]. The appearance of D. mutilia as one of the most consistently detected species on declining ash and the lack of an ex-type isolate inspired an extensive research into Diplodia species associated with Fraxinus spp. [16]. Within this research, a large collection of Diplodia strains, obtained from ash and other woody hosts with cankers and branch dieback, was subjected to morphological assessment and phylogenetic analysis. Consequently, D. fraxini was reinstated and placed as a distinct species within Diplodia clade 1 together with Diplodia mutila and Diplodia subglobosa sp. nov. Since D. mutila was found to be a species complex, some species associated with various hosts may have been incorrectly identified as D. mutila in the past. This could also explain the results from our BLAST search in NCBI, which generated both D. mutila and D. fraxini sequences with high similarity scores to our isolates.

Here we report for the first time the isolation of Diplodia fraxini from declining F. excelsior plantations in Bulgaria. The combined morphological, molecular, and physiological evidence confirmed the isolates as Diplodia fraxini and D. seriata. The established cardinal temperatures for D. fraxini isolates are in compliance with those reported for the type species [16]. Based on the observed growth rates of D. seriata isolate Dulovo 5, which thrives at temperatures between 25 and 30 °C, we infer that the pathogen is well suited to higher temperatures (Figure 6). The results from the pathogenicity tests clearly show that Diplodia fraxini can cause necrosis on ash—both on leaves and twigs (Figure 7)—and is involved in the investigated ash decline cases, although the limited sampling scope of this study should be acknowledged. The fraxitoxin, a secondary metabolite produced by D. fraxini which causes ash specific necrosis, most likely plays a key role in the pathogenicity of the fungus [26]. As far as we know, the association of Diplodia fraxini with F. excelsior dieback has been reported from Spain, [27] Italy [28], Slovenia [29], Germany [22], and Croatia [30].

In a recent study two distinct groups of major pathogens were found to play a prominent role in the ash dieback etiology observed in the forests of Central-Northern Italy, rather than H. fraxineus [31]. Evidently, these were prominent members of the Botryosphaeriaceae family and aggressive and emerging species of the Phytophthora genus, with the most commonly detected species being Phytophthora plurivora and Diplodia fraxini. The disease impact was higher on sites where ash trees grew under environmental stress (i.e., areas characterized by mild dry winters and hot summers with intense and prolonged drought) and exhibited reduced vigor, also as a consequence of anthropogenic interference (i.e., silvicultural management and fires). The identified causative agents are emerging pathogens that thrive under warmer conditions, with their impact in the investigated areas being prevalent compared to H. fraxineus, which appears to be restricted on the Italian peninsula to the cooler and wetter valleys of the Alps and Central-Northern Apennines. Although H. fraxineus was present, its impact appeared less significant than that of Botryosphaeriaceae and Phytophthora pathogens. A study investigating the weakening and decline of European ash and other ash species at different locations in the suburbs of Saint Petersburg, Russia, was carried out during the summer of 2019 and spring of 2020 [32]. It was found that Diplodia spp., pathogenic to ash branches, were consistently isolated throughout the study period. H. fraxineus was only found on fallen leaf petioles in the spring, not on samples from tree crowns. The study suggests that Diplodia spp. may be a primary cause of ash decline in the surveyed areas, potentially facilitated by H. fraxineus creating entry points for infection. The authors propose further research to understand the low pathogenicity of H. fraxineus in the region and the specific role of Diplodia spp. in ash dieback [32]. A recent study analyzed multilocus genotypes of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and its interactions with other fungi from stem collar necroses, providing insights into the fungal predominance in these lesions [33]. Diplodia fraxini and H. fraxineus were the most common morphotypes, occurring on all studied trees (100%), followed by Armillaria sp. (90%). It can be concluded that Diplodia fraxini undoubtedly contributes to a greater extent of damaged stem collars and therefore plays an important role in the development of this disease.

The role of Phytophthora spp. as a contributing factor in the decline of F. excelsior throughout Europe has been investigated by [34]. P. cactorum, P. plurivora, P. taxon salixsoil (currently Phytophthora lacustris Brasier, Cacciola, Nechwatal, Jung & Bakonyi), and P. gonapodyides were detected in the rhizosphere soil samples and necrotic bark lesions from declining ash trees in four stands in Poland and Denmark [34]. The conducted inoculation experiments with the obtained isolates confirmed their pathogenicity and provided evidence for the involvement of Phytophthora species as a contributing factor in ash decline. However, in our study we did not detect any Phytophthora species in the rhizosphere samples.

Diplodia seriata is reported as an important pathogen on grapevines [35]. The pathogen was also isolated from Fraxinus ornus and F. angustifolia in Europe [16]. Subsequently, ascomata of D. seriata were observed on F excelsior [28]. Our isolate did not produce necrotic lesions on the F. exelsior detached leaves and branch cuttings in the performed pathogenicity tests (Figure 7). In addition to D. fraxini and D. seriata, the fungi associated with ash twigs identified in this study (Table 1) are saprotrophs and weak pathogens, potentially contributing to the decline in overall tree health.

Diplodia spp. are endophytic fungi within the Botryosphaeriaceae family (Botryosphaeriales, Ascomycetes). Their latent phase and ability to rapidly cause disease when their hosts are under stress are well known [36]. In recent years there have been an increasing number of reports of severe damage to woody plants caused by Botryosphaeriaceae pathogens [37,38,39,40]. The number of disease reports attributed to members of this family has increased exponentially worldwide, from approximately 100 between 1960 and 2000 to over 1500 in the past two decades. It is drawing the attention of researchers, especially in the Mediterranean region, which is the second biodiversity hotspot on the planet [31]. The rise in the number of the described disease incidents caused by Botryosphaeriaceae members is largely due to the increased researcher interest, but also because of the predisposition of host plants by long-lasting droughts and other stresses, and such conditions are expected to become more common with climate change. Ash trees serve as keystone species in temperate forests, supporting diverse invertebrates, lichens, birds, and understory flora. Their decline leads to cascading effects on forest biodiversity, ecosystem structure, and nutrient cycling [41]. Recognizing D. fraxini as a primary contributing agent has direct implications for the forest-protective-belt management. The timely removal of infected material and avoidance of slash accumulation are essential to limit inoculum build-up. The observed susceptibility of ash highlights the need to reduce reliance on this genus in future plantings and to pursue diversification with drought- and disease-tolerant species. Adjustments to silvicultural practices, including targeted thinning to improve microclimatic conditions, minimization of mechanical injuries, and improved nursery hygiene, will further reduce host stress and pathogen spread. Finally, systematic monitoring supported by field diagnostics and remote sensing can improve early detection and support effective decision-making. This study provides the first evidence of Diplodia fraxini as a pathogenic species associated with Fraxinus excelsior decline in Bulgaria, confirming its ability to cause necrosis on ash tissues under certain environmental conditions. The findings underscore the significance of D. fraxini as an emerging pathogen in warmer climates, while D. seriata appeared non-pathogenic under the tested conditions. Nonetheless, the study’s conclusions are limited by the small sample size and the absence of long-term monitoring, which should be addressed in future investigations to strengthen understanding of these pathogens’ roles in ash decline.

5. Conclusions

Diplodia fraxini was the main fungal pathogen found to be associated with declining ash trees in the investigated ash stands. The invasive pathogen H. fraxineus was not found on the cankered branches, nor were its pseudosclerotia present on the ash petioles from the previous year. The decline of shelterbelt ash stands in Dobrudzha underscores the need for an integrated, climate-responsive forest management strategy. The confirmation of Diplodia fraxini as a principal pathogen emphasizes the importance of proactive phytosanitary measures and species diversification in ensuring the long-term functionality and resilience of shelterbelt systems. Establishing a standardized framework for integrated monitoring, reinforcing evidence-based silvicultural practices, and investing in adaptive restoration methodologies will be fundamental to ensuring the long-term conservation of biodiversity, the resilience of forest ecosystems, and the sustained provision of ecological and agroecosystem services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.L. and P.D.-M.; methodology: A.L. and P.D.-M.; software, validation, and formal analysis: A.L. and P.D.-M.; investigation: A.L. and P.D.-M.; resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation: A.L.; writing—review and editing: A.L. and P.D.-M.; visualization: A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Centre of Competence “Sustainable Utilization of Bio-resources and Waste of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants for Innovative Bioactive Products” (BIORESOURCES BG) project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0001, funded by the Program “Research, Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation” 2021–2027, co-funded by the EU.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Forest Protection station—Varna, the State Forest Enterprises in Dobrich, General Toshevo and Tutrakan and State Hunting Enterprises in Balchik and Karakuz-Dulovo, for the logistic support and the opportunity to collect the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beck, P.; Caudullo, G.; Tinner, W.; de Rigo, D. Fraxinus excelsior in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e0181c0+. [Google Scholar]

- Pautasso, M.; Aas, G.; Queloz, V.; Holdenrieder, O. European Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) Dieback—A Conservation Biology Challenge. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C.; Ellenberg, H. Ecology of Central European Forests: Vegetation Ecology of Central Europe, Volume I; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-43040-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, M.; Iliev, N.; Lissev, N.; Dermendzhiev, P.; Kamburov, I.; Burdarov, D.; Penchev, P. Guidelines for Restoration and Management of Riparian Forest Habitats in Bulgaria; WWF Bulgaria: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2018; Available online: https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/guidelines_for_restoration_and_management_of_riparian_forest_habitats.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dodev, Y.; Georgiev, G.; Georgieva, M.; Ivanov, V.; Belilov, S.; Madzhov, S.; Georgieva, L. Health Status of the Field Protective Forest Belts in Dobrudzha—Results from the Monitoring Carried out in 2022. Silva Balc. 2023, 24, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, M.; Gjonov, I.; Ivanov, V.; Belilov, S.; Dodev, Y.; Georgieva, L.; Mirchev, P.; Georgiev, G. Damage Caused by Singing Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) in the Field Protective Forest Belts in South Dobrudzha, Bulgaria. Hist. Nat. Bulg. 2024, 46, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastridis, A.; Stathis, D.; Sapountzis, M.; Theodosiou, G. Insect Outbreak and Long-Term Post-Fire Effects on Soil Erosion in Mediterranean Suburban Forest. Land 2022, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, T. Chalara fraxinea sp. nov. Associated with Dieback of Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Poland. For. Pathol. 2006, 36, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queloz, V.; Grünig, C.R.; Berndt, R.; Kowalski, T.; Sieber, T.N.; Holdenrieder, O. Cryptic Speciation in Hymenoscyphus albidus. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, H.-O.; Queloz, V.; Hosoya, T. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, the Correct Scientific Name for the Fungus Causing Ash Dieback in Europe. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovici, O.; Chira, D.; Kirisits, T. Ash Dieback New Agent—Hymenosyphus Fraxineus—In Suceava Plateau. Rev. Silvic. Cineg. 2014, 35, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Keča, N.; Kirisits, T.; Menkis, A. First Report of the Invasive Ash Dieback Pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus on Fraxinus excelsior and F. angustifolia in Serbia. Balt. For. 2017, 23, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sierra, A.; Jung, M.H.; Jung, T. Survey and Monitoring of Phytophthora Species in Natural Ecosystems: Methods for Sampling, Isolation, Purification, Storage, and Pathogenicity Tests. In Plant Pathology: Method and Protocols; Luchi, N., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 13–49. ISBN 978-1-07-162517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Werres, S. PROTOCOL 01-09.1: Preparation of Hyphal Tip Phytophthora Cultures. In Laboratory Protocols for Phytophthora Species; Sabine, W., Ed.; Protocols; The American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2015; pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-89054-496-9. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.; Innis, M.; Gelfand, D.; Sninsky, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 31, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Deidda, A.; Scanu, B.; Phillips, A.J.L. The Complex of Diplodia Species Associated with Fraxinus and Some Other Woody Hosts in Italy and Portugal. Fungal Divers. 2014, 67, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarenkov, K.; Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; May, T.W.; Frøslev, T.G.; Pawlowska, J.; Lindahl, B.; Põldmaa, K.; Truong, C.; et al. The UNITE Database for Molecular Identification and Taxonomic Communication of Fungi and Other Eukaryotes: Sequences, Taxa and Classifications Reconsidered. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D791–D797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. An Integrated Approach to the Analysis of Variation in Phytophthora Nicotianae and a Redescription of the Species. Mycol. Res. 1993, 97, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R.; Vasaitis, R.; Barklund, P.; Thomsen, I.M.; Stenlid, J. Occurrence and Pathogenicity of Fungi in Necrotic and Non-Symptomatic Shoots of Declining Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Sweden. Eur. J. For. Res. 2009, 128, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, V.; Børja, I.; Hietala, A.M.; Kirisits, T.; Solheim, H. Ash Dieback: Pathogen Spread and Diurnal Patterns of Ascospore Dispersal, with Special Emphasis on Norway. EPPO Bull. 2011, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacia, A.; Borowik, P.; Hsiang, T.; Marozau, A.; Matić, S.; Oszako, T. Ash Dieback in Forests and Rural Areas—History and Predictions. Forests 2023, 14, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Fuchs, S.; Bien, S.; Bußkamp, J.; Langer, G.J.; Langer, E.J. Fungi Associated with Stem Collar Necroses of Fraxinus excelsior Affected by Ash Dieback. Mycol. Prog. 2023, 22, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, M.; Webber, J.; Boddy, L. Current Understanding and Future Prospects for Ash Dieback Disease with a Focus on Britain. Forestry 2024, 97, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybył, K. Fungi Associated with Necrotic Apical Parts of Fraxinus excelsior Shoots. For. Pathol. 2002, 32, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, T.; Kraj, W.; Bednarz, B. Fungi on Stems and Twigs in Initial and Advanced Stages of Dieback of European Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Poland. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Maddau, L.; Masi, M.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Pescitelli, G.; Evidente, A. Fraxitoxin, a New Isochromanone Isolated from Diplodia Fraxini. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, G.; León, M.; Abad-Campos, P.; Armengol, J.; Mateu-Andrés, I.; Güemes-Heras, J. First Report of Diplodia Fraxini Causing Dieback of Fraxinus Angustifolia in Spain. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaldeddu, B.; Bottecchia, F.; Bregant, C.; Maddau, L.; Montecchio, L. Diplodia Fraxini and Diplodia Subglobosa: The Main Species Associated with Cankers and Dieback of Fraxinus excelsior in North-Eastern Italy. Forests 2020, 11, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaldeddu, B.T.; Bregant, C.; Montecchio, L.; Brglez, A.; Piškur, B.; Ogris, N. First Report of Diplodia Fraxini and Diplodia Subglobosa Causing Canker and Dieback of Fraxinus excelsior in Slovenia. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlović, J.K.; Bregant, C.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Montecchio, L.; Volenec, I.; Uidl, K.; Diminić, D. Diplodia Fraxini: The Main Pathogen Involved in the Ash Dieback of Fraxinus Angustifolia in Croatia. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, A.; Bregant, C.; Aglietti, C.; Rossetto, G.; Tolio, B.; Moricca, S.; Linaldeddu, B.T. Pathogenic Fungi and Oomycetes Causing Dieback on Fraxinus Species in the Mediterranean Climate Change Hotspot Region. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1253022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabunin, D.A.; Selikhovkin, A.V.; Varentsova, E.Y.; Musolin, D.L. Decline of Fraxinus excelsior L. in Parks of Saint Petersburg: Who Is to Blame—Hymenoscyphus fraxineus or Diplodia spp.? For. Stud. 2021, 73, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Gruschwitz, N.; Bien, S.; Fuchs, S.; Bubner, B.; Blunk, V.; Langer, G.J.; Langer, E.J. The Fungal Predominance in Stem Collar Necroses of Fraxinus excelsior: A Study on Hymenoscyphus fraxineus Multilocus Genotypes. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, L.B.; Ptaszek, M.; Rodziewicz, A.; Nechwatal, J.; Thinggaard, K.; Jung, T. Phytophthora Root and Collar Rot of Mature Fraxinus excelsior in Forest Stands in Poland and Denmark. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, A.; Cibelli, F.; Lops, F.; Raimondo, M.L. Characterization of Botryosphaeriaceae Species as Causal Agents of Trunk Diseases on Grapevines. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J. Botryosphaeriaceae as Endophytes and Latent Pathogens of Woody Plants: Diversity, Ecology and Impact. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchi, N.; Oliveira Longa, C.M.; Danti, R.; Capretti, P.; Maresi, G. Diplodia Sapinea: The Main Fungal Species Involved in the Colonization of Pine Shoots in Italy. For. Pathol. 2014, 44, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatković, M.; Keča, N.; Wingfield, M.J.; Jami, F.; Slippers, B. New and Unexpected Host Associations for Diplodia Sapinea in the Western Balkans. For. Pathol. 2017, 47, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.M.; Hantula, J.; Wingfield, M.; Drenkhan, R. Diplodia Sapinea Found on Scots Pine in Finland. For. Pathol. 2019, 49, e12483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. Special Issue on Botryosphaeriaceae. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łubek, A.; Kukwa, M.; Czortek, P.; Jaroszewicz, B. Impact of Fraxinus excelsior Dieback on Biota of Ash-Associated Lichen Epiphytes at the Landscape and Community Level. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).