Abstract

Understanding the social drivers of pro-environmental behavior in urban forests and green spaces is critical for addressing sustainability challenges. Subjective norms serve as a key pathway through which social expectations influence individuals’ behavioral intentions. Despite mixed findings in the literature regarding the impact of subjective norms on individuals’ intentions, there is a research gap about the determinants of this construct. This study was conducted to explore how social expectations shape perceived subjective norms among visitors of urban forests. A theoretical model was developed with subjective norms at its center, incorporating their predictors including social identity, media influence, interpersonal influence, and institutional trust, personal norms as a mediator, and behavioral intention as the outcome variable. Using structural equation modeling, data was collected and analyzed from a sample of visitors of urban forests in Tehran, Iran. The results revealed that subjective norms play a central mediating role in linking external social factors to behavioral intention. Social identity emerged as the strongest predictor of subjective norms, followed by media and interpersonal influence, while institutional trust had no significant effect. Subjective norms significantly influenced both personal norms and intentions, and personal norms also directly predicted intention. The model explained 50.9% of the variance in subjective norms and 39.0% in behavioral intention, highlighting its relatively high explanatory power. These findings underscore the importance of social context and internalized norms in shaping sustainable behavior. Policy and managerial implications suggest that strategies should prioritize community-based identity reinforcement, media engagement, and peer influence over top-down institutional messaging. This study contributes to environmental psychology and the behavior change literature by offering an integrated, empirically validated model. It also provides practical guidance for designing interventions that target both social and moral dimensions of environmental action.

1. Introduction

Urban forests and green spaces maintain a reciprocal and interdependent relationship with urban populations. These natural infrastructures offer a multitude of ecosystem services ranging from environmental regulation to social, cultural, and economic benefits that enhance the quality of life in urban settings [1,2]. Conversely, the effective conservation and sustainable management of these green assets are contingent upon the environmentally responsible behaviors and active engagement of citizens [3,4]. Understanding why individuals engage in behaviors, particularly those that benefit society, such as pro-environmental actions in urban green spaces has long been a central concern across the social and behavioral sciences [5,6]. Within this landscape, social influence has emerged as one of the most powerful and consistent predictors of human behavior [7]. From early psychological theories to contemporary behavioral models, the idea that individuals are not isolated decision-makers but are instead embedded within social contexts has gained widespread empirical support. Models such as the theory of reasoned action [8]), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [9], social cognitive theory [10], and the Norm Activation Model (NAM) [11] all incorporate social influence in various forms, recognizing that perceptions of what others think or do play a critical role in shaping people’s intentions and behaviors.

These theories consistently demonstrate that individuals frequently consider the attitudes, expectations, and actions of others when forming intentions, especially in domains where behavior has moral, social, or collective implications, such as environmental responsibility behaviors in urban green spaces [3,12]. The notion of being observed, judged, or expected to conform to social norms serves as a cognitive and emotional force that either facilitates or constrains behavior [13]. Among the theoretical models that integrate social influence, the TPB [14] has become one of the most widely applied and empirically tested frameworks in pro-environmental behavioral research [15,16]. TPB posits that intention, the most immediate predictor of behavior, is shaped by three core constructs: attitude toward the behavior, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms [14]. While attitude [17] and perceived behavioral control [18] have often received extensive scholarly attention, subjective norms have been relatively underexplored or inconsistently reported in empirical studies.

Despite its theoretical importance, the empirical findings on the effect of subjective norms have been mixed. In some studies, subjective norms significantly influence behavioral intentions [19,20], while in others, their effects on behaviors such as consumption-related actions, participation in environmental conservation, workplace-related environmental behaviors, and broader sustainable environmental practices were marginal or statistically insignificant [21,22]. These inconsistencies suggest that the functioning of subjective norms may be contingent upon deeper, context-specific, or unmeasured factors that influence how people perceive and internalize social expectations. Most studies applying the TPB tend to treat subjective norms as a static and exogenous construct [23,24], rather than exploring the dynamic social and psychological mechanisms that shape them. As a result, there remains a lack of clarity about why subjective norms significantly influence intention in some settings but not in others, and which specific sources of normative pressure matter most in motivating sustainable behavior. In this regard, there is a research gap. Research exploring the influence of social pressure or expectations on individuals’ subjective norms regarding pro-environmental behavior in forests and urban green spaces remains limited. These limitations not only weaken the predictive capacity of TPB-based models but also hinder the development of effective interventions aimed at promoting sustainable behavior through social influence.

In response to the identified gaps, the present study aims to investigate who and what shapes subjective norms in the context of pro-environmental behavior in urban forests and green spaces in Tehran, the capital city of Iran. Tehran serves as an appropriate case study for examining cities with similar environmental and socio-cultural characteristics. Situated in a semi-arid region and frequently exposed to heatwaves, air pollution from traffic and industry, and dust storms, the city relies heavily on its urban forests and green spaces to mitigate environmental stressors and promote a healthier urban environment [25]. However, the city’s vast scale and widespread distribution of green spaces present significant challenges for the management and conservation of these resources, challenges that cannot be addressed without environmentally responsible behavior and active public participation. Moreover, Tehran’s socio-cultural context, characterized by a strong orientation toward collective behavior and responsiveness to social expectations, makes it a suitable setting for investigating the role of subjective norms [26]. Insights gained from this study in Tehran can offer important implications for similar urban contexts, contributing to a deeper understanding of the determinants of subjective norms as key drivers of pro-environmental behavioral intention.

This study moves beyond traditional TPB applications by unpacking the complex mechanisms underlying social influence, offering a more nuanced understanding of behavioral intention formation. The findings of this study are expected to provide theoretical contributions by enriching the normative component of TPB and practical implications for designing more effective sustainability campaigns, social interventions, and policy messaging. In a world increasingly shaped by collective challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation, understanding the social roots of behavior is not only an academic necessity but also a societal imperative. This research introduces a conceptual model in which subjective norms are treated as a dependent construct, shaped by key antecedents

1.1. Theoretical Framework of Research

Theoretical models of human behavior have long recognized that individuals rarely act in isolation. Instead, their attitudes, decisions, and actions are embedded in a web of social relationships and contextual influences [27,28,29]. A consistent insight across multiple behavioral paradigms is the significance of social norms and perceived expectations in shaping behavioral outcomes. Within this context, social influence emerges as a central pillar across several foundational behavioral models including social cognitive theory, Value–Belief–Norm (VBN), and NAM [11,30], highlighting social norms and value activation as key drivers of pro-environmental action. These models, though differing in structure and emphasis, converge on a common insight that society, through institutions, media, communities, and interpersonal networks, plays a formative role in shaping individual behavioral choices. However, despite this broad recognition, many mainstream models such as the TPB have often operationalized social influence in narrow or static ways, limiting the explanatory power of key constructs like subjective norms. This variable represents the perceived social pressure an individual experiences to perform or refrain from a particular behavior. These social pressures originate from important referents such as family members, friends, colleagues, or society at large.

The NAM and VBN theory are both foundational models in the environmental psychology literature that emphasize the role of internal moral obligations in shaping behavior. NAM posits that individuals act pro-socially when they are aware of the consequences of their actions and feel a personal responsibility to act [11]. This leads to the activation of personal norms, which are internalized feelings of moral obligation. VBN theory, developed by [30], expands NAM by linking values, ecological worldviews, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms into a causal chain that predicts pro-environmental behavior. While NAM and VBN focus on internalized moral motivation, the TPB [31] provides a broader social–psychological framework by identifying three primary antecedents of intention, including subjective norms. In this study, we draw on all three theories. TPB is used as the primary framework to explain behavioral intention, with subjective norms positioned as a central variable. However, acknowledging the influence of deeper moral values and obligations, we integrate concepts from NAM and VBN to examine how subjective norms may give rise to personal norms, which then influence pro-environmental intentions. Thus, our model bridges external social influence (TPB) with internal moral motivation (NAM and VBN), offering a more comprehensive account of how both societal expectations and moral beliefs shape environmentally responsible behavior.

A central premise of this extended framework is that subjective norms emerge from a complex interplay of interpersonal influences, media exposure, institutional trust, moral norms, and social identity. Each of these factors contributes uniquely to how individuals perceive social expectations about environmental behavior: These variables were selected based on their theoretical relevance and empirical support in the literature, and together, they offer a multidimensional understanding of how normative beliefs are formed and activated. Within the TPB, subjective norms are defined as an individual’s perception of social pressure from important others to perform or not perform a given behavior [32]. They reflect how much a person believes that key referents expect them to act in a certain way. In contrast, personal norms, a concept often drawn from the NAM, refer to an individual’s internalized moral obligations or feelings of responsibility to engage in a behavior, independent of external social expectations [11]. Social norms are a broader term that encompasses both descriptive norms (perceptions of what others typically do) and injunctive norms (perceptions of what others think one should do), and they may influence behavior through both interpersonal and societal-level processes [33]. In the context of TPB, subjective norms represent a specific operationalization of social norms, limited to perceived expectations from salient referents. While social norms form the structural context of behavioral influence, subjective norms capture how individuals internalize these influences, and personal norms reflect the internal moral transformation of such social cues. Understanding the conceptual boundaries and interconnections among these constructs is critical for accurately modeling the motivational pathways underlying pro-environmental behaviors.

Interpersonal influence refers to the ways in which the actions, attitudes, or communications of others shape an individual’s intentions and subsequent behaviors [34]. This process is central to social psychology, communication studies, and behavioral research [35]. Interpersonal influence reflects the role of immediate social networks of family, friends, and colleagues, who communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations through direct interaction and social approval [36]. Given the strong emotional and social ties within these networks, their influence is often immediate and tangible. Research has confirmed the positive influence of this variable on subjective norms of intention in public transportation [37], green marketing [38], purchase intention [35]. Accordingly, this research hypothesized that interaction with the peer group, family, and other important people can shape a portion of perceived social expectations.

Media influence captures the growing importance of environmental communication disseminated through traditional and social media channels [39]. These sources serve as conduits for normative messages, shaping perceptions of what behaviors are socially desirable and widely accepted [40]. Media, particularly social media, plays a pivotal role in shaping subjective norms by providing social cues, peer feedback, and influencer endorsements that create perceived social expectations [41]. These norms then strongly influence individual intentions and behaviors across various domains. In fact, subjective norms can function as a mediating mechanism for the influence of media [40] In this context, when individuals receive messages from others and society about a specific behavior, they come to understand the societal expectations regarding that behavior. This study assumes that media can act as one of the key antecedents of subjective norms, shaping individuals’ perceptions of social expectations concerning pro-environmental behavior in forests and urban green spaces, and thereby influencing their behavioral intentions.

Institutional trust represents confidence in the legitimacy and credibility of organizations and authorities that advocate for environmental norms [42]. When individuals trust these institutions, they are more likely to accept their messages and incorporate them into their normative beliefs [43]. Governmental institutions and public organizations can be regarded as integral parts of society that expect citizens to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, particularly in the protection of urban forests [44]. Public trust in these institutions, specifically those responsible for managing urban forests, can play a crucial role in strengthening individuals’ behavioral intentions toward conservation [45]. This study aims to explore the pathway through which such institutional trust influences behavioral intention, focusing on the mediating role of subjective norms.

Social identity emphasizes the extent to which individuals see themselves as part of a group that values environmental sustainability. Strong identification with pro-environmental communities heightens sensitivity to group norms and expectations.

Environmental moral norms or personal norms reflect internalized moral obligations arising from one’s values and beliefs about right and wrong environmental conduct [46]. These norms interact with external social pressures to strengthen or weaken subjective norms [47]. Subjective norms often originate from external social expectations, while moral norms are internal standards of right and wrong [48]. Research suggests that subjective norms can influence the development of moral norms [49]. Specifically, the beliefs and expectations of reference groups may be internalized over time and become part of an individual’s moral framework. Moral norms can act as a bridge between subjective norms and behavioral intentions [50]. This means that social pressures may first shape a person’s moral beliefs, which then influence their intentions and actions. In this study, it is hypothesized that subjective norms not only have a direct effect on behavioral intention but also influence it indirectly through the formation of personal norms. This pathway is conceptualized as follows: subjective norms first shape personal norms, which in turn affect individuals’ behavioral intentions.

Social identity is the part of an individual’s self-concept that derives from their perceived membership in social groups, such as ethnicity, nationality, religion, occupation, or political affiliation [51]. It reflects how people define themselves based on group memberships rather than solely on personal traits [52]. Social identity plays a crucial role in shaping subjective norms and, consequently, environmental intentions. When individuals strongly identify with a social group such as environmentalists, community members, or peers with pro-environmental values, they are more likely to internalize the group’s normative expectations [53]. This sense of belonging fosters conformity to the group’s environmental standards, thereby strengthening subjective norms that favor sustainable behavior [54]. As these norms become more salient, they significantly enhance individuals’ intentions to engage in environmentally responsible actions, reflecting the influence of collective identity on personal decision-making.

By integrating these antecedents, the framework provides a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of subjective norms, enabling researchers to explain variations in normative influence across individuals and contexts. This approach moves TPB closer to capturing the complex social realities that shape pro-environmental intentions and behaviors. Practically, understanding the distinct drivers of subjective norms equips policymakers, communicators, and environmental advocates with actionable insights. For instance, interventions can be tailored to leverage interpersonal networks by engaging key influencers within families or peer groups to amplify normative messages. Likewise, strategic use of media channels—both traditional and social—can enhance public awareness and shape perceptions of widespread social approval for sustainable practices. The importance of institutional trust highlights the need for transparent, consistent, and credible communication from environmental organizations and authorities to build normative legitimacy. Recognizing the role of moral norms and social identity suggests that fostering a sense of ethical obligation and belonging to environmentally conscious communities can deepen commitment and adherence to pro-environmental behaviors. Furthermore, this framework is highly relevant in the contemporary global context, where environmental challenges such as climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss demand collective action. The social dimension of behavior—how individuals perceive and internalize societal expectations—plays a crucial role in mobilizing such action. By offering a comprehensive model of the social roots of subjective norms, this research contributes to designing more effective, socially grounded interventions that harness normative influence as a catalyst for sustainable change.

1.2. Hypothesis Definition

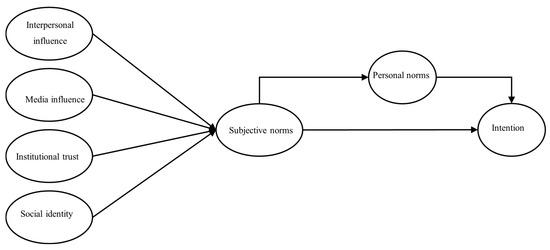

Drawing on the theoretical foundations presented in the previous section, such as the TPB, the NAM, and the VBN, this study formulated a series of hypotheses to empirically test the pathways through which normative influences shape pro-environmental behavioral intention. The proposed conceptual model integrates both social and personal normative constructs to explain the formation of behavioral intentions in the environmental context. At the core of the model lies the construct of subjective norms. These subjective norms are hypothesized to be influenced by key antecedents, including interpersonal influence, media influence, institutional trust, and social identity, reflecting a combination of personal and interpersonal motivational sources. The model further posits that subjective norms do not operate in isolation but may lead to the activation of personal norms, which represent individuals’ internalized moral obligations to act in environmentally responsible ways. This assumption draws from NAM and VBN theory, which emphasize that moral norms are central predictors of behavior [11,30]. Finally, the model proposes that personal norms serve as a proximal predictor of behavioral intention, reflecting the internal motivational force that transforms social influence into deliberate commitment. In this framework, subjective norms function as both a direct antecedent to behavioral intention and an indirect one through personal norms, thereby bridging external social pressures and internal moral drivers. The following hypotheses are developed to examine these proposed relationships and validate the integrative theoretical framework guiding this research. These hypotheses are also illustrated in the graphical model of the research, presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of research.

H1.

Interpersonal influence has a positive impact on individuals’ perceived subjective norms about pro-environmental behaviors in urban forests.

H2.

Media has a positive impact on individuals’ perceived subjective norms about pro-environmental behaviors in urban forests.

H3.

Institutional trust has a positive impact on individuals’ perceived subjective norms about pro-environmental behaviors in urban forests.

H4.

Social identity has a positive impact on individuals’ perceived subjective norms about pro-environmental behaviors in urban forests.

H5.

Subjective norms positively influence personal norms.

H6.

Subjective norms influence pro-environmental intention.

H7.

Personal norms have positive influence on pro-environmental intention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location of Research

This study was conducted in the megacity of Tehran, which has a population of nearly nine million people. Tehran is located in an arid and semi-arid region and has an average per-capita green space of only 6 square meters [55], unevenly distributed across the city. The vast urban area, the diverse nature of urban green spaces in terms of scale and function, and the high maintenance costs for the government have rendered the effective management of these resources highly dependent on citizens’ cooperation, particularly through their pro-environmental behaviors and commitment to conservation.

2.2. Statistic Population and Sampling

The target population for this study comprised visitors to urban forests and green spaces in Tehran. Given that the aim of this research was to examine pro-environmental behavior during the use of these urban green resources, visitors—being the most engaged group in this context—were identified as the appropriate population for investigation. Based on the sample size determination table in [56], a minimum of 384 participants was deemed necessary. However, to enhance the precision and coverage of this study, a larger sample was collected, and ultimately, data from 421 participants were included in the final analysis. A multi-stage cluster sampling method was employed to select participants. In the first stage, all 22 municipal districts of Tehran were considered, from which 10 districts were selected to ensure geographic diversity across the city. In the next stage, within each selected district, two to three urban forests or green spaces were identified. At these locations, participants were selected randomly for data collection.

2.3. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out using a two-part questionnaire. The first section gathered socio-economic information about the participants. The second section included items related to the constructs of the research model. This part consisted of 31 items designed to measure the latent variables in the model, all of which were assessed using a five-point Likert scale. The Likert scale is widely accepted in social science research for its ability to capture the degree of agreement or disagreement with various statements, making it especially useful for modeling latent psychological constructs within structured frameworks [57], such as the model of this study. Prior to the main data collection phase, the questionnaire underwent a two-stage validation process. First, it was reviewed by a panel of five experts in the field to assess content validity. Following that, a pilot test was conducted with 30 participants, and the instrument was refined accordingly. The questionnaire was approved in both stages and subsequently used for the full-scale data collection. As described in the previous section, the target population of this study consisted of visitors to urban forests, and respondents were selected from among these individuals. At each sampling location, participants were chosen using a random sampling approach. Initially, participants were informed about the purpose of this study and the data collection procedure. They were then asked whether they were willing to participate. Those who agreed were provided with a questionnaire, along with instructions on how to complete it. Participants were then given the opportunity to complete the questionnaire in a private setting. As noted earlier, all questionnaires were administered and completed in person through face-to-face interviews. All participants provided informed written consent before participating in this study. They were also assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. Data were collected during March and April 2025.

2.4. Data Analysis

To evaluate the conceptual model and examine the hypothesized relationships among latent variables, structural equation modeling using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach was employed. PLS-SEM is especially suitable for theory development and prediction-oriented research, particularly when the model includes multiple constructs and complex pathways, and when the primary objective is to assess the relationships among latent variables rather than to confirm a well-established theory [58]. This method also provides greater flexibility with respect to the sample size and data normality, making it appropriate for this study’s empirical context. The analytical procedure followed a two-step modeling approach. In the first step, the measurement model was assessed to establish the reliability and validity of the constructs, including evaluations of indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Once these conditions were satisfied, the structural model was examined to test the hypothesized relationships among constructs.

2.4.1. Test of Reliability and Validity

To ensure the robustness and precision of the structural equation modeling results, the reliability and validity of the measurement model were evaluated through multiple indicators. These assessments were essential for confirming that the latent constructs in this study were measured accurately and consistently. Internal consistency reliability was first assessed through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal consistency reliability, which assesses how closely related a set of items are as a group. It indicates the extent to which the items of a construct measure the same underlying concept. A Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.70 is generally considered acceptable, indicating satisfactory reliability of the construct [59]. Similarly, CR offers a more refined measure by accounting for the actual factor loadings of the items, with a threshold of 0.70 considered acceptable [58]. Convergent validity was evaluated using the average variance extracted (AVE) as well as the factor loadings of the individual indicators. AVE measures the extent to which a construct explains the variance in its indicators, with a value of 0.50 or higher indicating that the construct accounts for the majority of the variance in its observed variables.

To confirm that the constructs were empirically distinct from each other, discriminant validity was assessed using both the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). The Fornell and Larcker criterion is a widely used method for assessing discriminant validity in structural equation modeling. It works by comparing the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlations between that construct and all others in the model [60]. If the square root of a construct’s AVE is higher than its correlation with any other construct, it suggests that the construct shares more variance with its own indicators than with other constructs. This provides evidence that the construct is empirically distinct, supporting discriminant validity. The HTMT ratio is a modern technique used to evaluate discriminant validity in structural equation modeling. It assesses whether two constructs that are supposed to be distinct are actually different in practice. The HTMT value is calculated by comparing the average correlations across different constructs (heterotrait) with the average correlations within the same construct (monotrait). If the HTMT value is too high, it suggests that the constructs may not be truly separate. As a general rule, an HTMT value below 0.85 indicates good discriminant validity, meaning the constructs are likely measuring different concepts [61]. Finally, to examine the potential issue of multicollinearity among the indicators, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated. VIF values above 5 typically indicate problematic levels of collinearity, which can distort regression coefficients and compromise the integrity of the model. In this study, all VIF values were found to be comfortably below the recommended cutoff, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern. This confirms that the constructs in the model do not exhibit overlapping explanatory power to a degree that would undermine the analysis.

In addition to evaluating the reliability and validity of the measurement model, the potential for common method bias was examined using Harman’s single-factor test [62]. This approach involves conducting an exploratory factor analysis on all items in the dataset using principal component analysis without rotation. The rationale behind this test is that if a substantial portion of the variance is explained by a single factor, common method variance (CMV) may be a concern.

2.4.2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Test

To estimate the path coefficients and evaluate their statistical significance, the bootstrapping method was applied with 5000 subsamples. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric resampling technique that generates standard errors and confidence intervals for parameter estimates, allowing for robust significance testing without assuming a normal distribution of the data. For each hypothesized path, standardized regression coefficients (β), t-values, and p-values were calculated, and a path was considered significant if the associated t-value exceeded the critical threshold based on a 95% confidence level (typically, t > 1.96 for p < 0.05 in a two-tailed test). Additionally, the model’s explanatory power was assessed by calculating the coefficient of determination (R2) for each endogenous latent variable. R2 values reflect the proportion of variance in the dependent variables explained by the predictors in the model, serving as an indicator of the model’s overall predictive relevance.

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Participants

The demographic profile of the 421 participants is presented in Table 1. In terms of gender distribution, 53% of the respondents were male, while 47% were female, indicating a relatively balanced representation. Regarding age, participants under the age of 30 comprised 24% of the sample, those aged between 30 and 40 accounted for 25%, individuals in the 40–50 age group made up the largest portion at 30%, and those over 50 represented 22% of the sample. That distribution suggests that this study captured responses across a broad age spectrum, with a slight concentration in the middle-aged cohort. Marital status showed that 54% of participants were single, while 46% were married, reflecting a modest predominance of single individuals in the sample. In terms of educational attainment, 43% of respondents held a high school diploma or lower, 38% had obtained a bachelor’s degree, and 19% reported having a postgraduate degree. This distribution illustrates a diverse educational background among the participants, with a substantial portion possessing higher education qualifications.

Table 1.

Profile of participants.

3.2. The Results of Reliability and Validity Test

The results of reliability and convergent validity of the latent constructs are discussed in this section. As shown in the Table 2, all constructs demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.73 to 0.84, all of which exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating acceptable reliability [59]. The highest reliability was observed for media influence (α = 0.84), followed closely by institutional trust (α = 0.84) and subjective norms (α = 0.81). The lowest but still acceptable value was found for interpersonal influence (α = 0.73). In addition to alpha, CR scores for all constructs exceeded the 0.70 benchmark, suggesting that the measurement model yields consistent results across items measuring each construct. Convergent validity was assessed through AVE values. All constructs surpassed the minimum recommended value of 0.50 [61], with AVE scores ranging from 0.55 (interpersonal influence) to 0.67 (institutional trust). These results indicate that a substantial proportion of variance in the indicators is captured by the latent constructs, supporting convergent validity. The findings provide strong evidence for the reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model. All constructs meet or exceed conventional criteria, confirming that the measures used in this study are both consistent and valid representations of their respective theoretical concepts.

Table 2.

The results of reliability and validity.

The results of the Fornell and Larcker test (Table 3) demonstrate satisfactory discriminant validity across all constructs. The square root of the AVE for institutional trust was 0.819, which is greater than its correlations with other variables, including media influence (0.444), intention (0.273), and subjective norms (0.174). Similarly, intention displayed a square root of AVE of 0.806, exceeding its correlations with subjective norms (0.590) and social identity (0.578). The construct interpersonal influence had a square root of AVE of 0.740, which was greater than its highest correlation with personal norms (0.510). Likewise, the square roots of AVEs for media influence (0.782), personal norms (0.739), social identity (0.795), and subjective norms (0.765) were all higher than their respective inter-construct correlations. These findings confirm that each construct shares more variance with its own measurement items than with other constructs in the model, thereby supporting the discriminant validity of the measurement model [60]. The results of Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 24.9% of the total variance, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%. Therefore, CMV does not appear to pose a significant threat to the validity of the findings in this study [62].

Table 3.

The results of Fornell and Larcker test.

The results of the HTMT analysis (Table 4) indicated that all inter-construct HTMT ratios fell below the critical threshold of 0.85. For example, the HTMT value between intention and subjective norms was 0.711, and between social identity and intention was 0.672, both well below the cutoff. Similarly, the HTMT ratio between personal norms and interpersonal influence was 0.651, and between social identity and personal norms was 0.630. The lowest HTMT value was observed between institutional trust and interpersonal influence (0.139), indicating a strong distinction between these constructs. Overall, these findings provide robust evidence for discriminant validity based on the HTMT approach. Each construct is empirically distinct from the others, reinforcing the integrity of the measurement model and supporting the assumption that the constructs measure unique conceptual domains.

Table 4.

The results of HTMT test.

3.3. The Results of Structural Model and Hypotheses Test

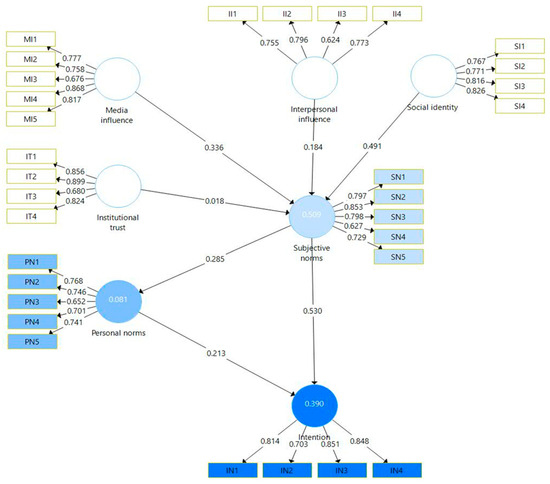

The evaluation of the structural model (Figure 2) provided critical insights into the relationships among the key latent constructs and the hypothesized pathways (Table 5) proposed in this study. Path coefficients, t-statistics, and corresponding p-values were examined to assess the strength and significance of these relationships. Among the predictors of subjective norms, social identity (H4) demonstrated the strongest and most significant influence (β = 0.491, t = 18.185, p < 0.001). This finding underscores the central role of social group affiliation in shaping individuals’ perceptions of expected environmental behavior. It confirms that individuals who identify more strongly with a social group are more likely to internalize the group’s environmental expectations. Media influence (H2) also exhibited a significant positive effect on subjective norms (β = 0.336, t = 8.269, p < 0.001), reflecting the pervasive impact of media in shaping public discourse and perceived societal norms regarding environmental responsibility. Similarly, interpersonal influence (H1) significantly predicted subjective norms (β = 0.184, t = 4.916, p < 0.001), suggesting that direct interactions with peers, friends, and family members contribute meaningfully to an individual’s perception of what behaviors are socially expected or appropriate.

Figure 2.

The structural model of research.

Table 5.

The results of hypothesis testing.

In contrast, institutional trust (H3) did not have a significant impact on subjective norms (β = 0.018, t = 0.463, p = 0.64). This result implies that trust in governmental or formal institutions does not substantially shape individuals’ perceptions of normative expectations concerning environmental behaviors in the studied context. Turning to the downstream effects, subjective norms were found to be a strong and significant predictor of both personal norms (H5) (β = 0.285, t = 7.398, p < 0.001) and behavioral intention (H6) (β = 0.530, t = 14.797, p < 0.001). These findings validate the theoretical proposition that subjective norms not only reflect perceived social pressures but also serve as a mechanism for the internalization of these expectations into personal moral obligations. Furthermore, personal norms significantly influenced behavioral intention (H7) (β = 0.213, t = 5.663, p < 0.001), indicating that internalized moral obligations play an essential role in motivating individuals to engage in environmentally responsible behavior. The explanatory power of the model was further substantiated by the R2 values. The model accounted for 50.9% of the variance in subjective norms and 39.0% of the variance in behavioral intention. These values indicate a moderate to substantial explanatory capacity and confirm that the model captures a significant portion of the variance in the key dependent variables. The structural model findings provide compelling evidence for the importance of social identity, media, and interpersonal communication in shaping normative beliefs, which in turn strongly influence both moral responsibility and behavioral intentions.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the determinants of subjective norms among visitors to urban forests. The structural model proposed in this study significantly enhances current understanding of the social underpinnings of pro-environmental behavioral intention in urban green spaces. Unlike conventional frameworks that treat subjective norms as exogenous and often static [32,63], this model reconceptualizes subjective norms as a dependent construct, shaped by multiple antecedents. Empirical results support the robustness of the structural model. The model explains 50.9% of the variance in subjective norms and 39.0% of the variance in behavioral intention, values that indicate moderate to substantial explanatory power within behavioral research. The results of the study showed that subjective norms explained more than one-third of the variance in behavioral intention, which is consistent with findings from previous research employing the TPB [64,65]. The model also confirms the mediating role of subjective norms between external influences and behavioral intention, aligning with the notion that social pressure must first be internalized as moral obligation before guiding behavior. The positive indirect pathway from subjective norms to intention via personal norms further substantiates the model’s theoretical sophistication.

The findings provide robust support for Hypothesis 1, which posited that interpersonal influence significantly shapes individuals’ perceived subjective norms concerning pro-environmental behaviors in urban forests. This result aligns with core assumptions in social psychology that interpersonal relationships serve as primary conduits for normative influence, particularly through mechanisms such as social approval, conformity, and relational obligations [66]. Family members, close friends, and peers are often the most salient reference groups in individuals’ daily lives [67]. Their expressed attitudes and behavioral expectations create an immediate and emotionally resonant normative environment, which in turn influences what people perceive as socially acceptable or desirable actions. This finding reinforces earlier research in environmental behavior and communication that underscores the persuasive power of interpersonal networks in shaping sustainability-related subjective norms and choices [68] In the context of urban green space engagement, where behaviors are often visible and socially situated, interpersonal signals carry additional weight [3]. However, by treating interpersonal influence as an exogenous antecedent of subjective norms rather than conflating the two, this study offers greater conceptual clarity and empirical precision. Furthermore, the strength of this relationship, though smaller in magnitude than that of media or social identity, suggests that interpersonal influence operates as a foundational yet context-sensitive driver of norm formation.

The empirical support for Hypothesis 2 is strong and statistically significant, confirming that media influence positively shapes individuals’ subjective norms regarding pro-environmental behavior in urban forests. This finding highlights the increasingly pivotal role of media in the normative construction of environmental behavior. By continuously exposing individuals to environmental messages, value-laden narratives, public endorsements, and peer behaviors, media establishes behavioral referents that shape what is perceived as normal or approved within a society [69,70]. The strength of this relationship suggests that media does more than raise environmental awareness; it actively participates in shaping the perceived social expectations that underlie subjective norms. This is consistent with previous findings in environmental communication and behavioral science, where media exposure has been shown to mediate or amplify pro-environmental intentions [71]. Practically, this finding underscores the importance of media campaigns that go beyond information dissemination to actively leverage normative messaging highlighting what others are doing, approving, or expecting in the realm of sustainable behavior.

Contrary to expectations, Hypothesis 3 was not supported by the empirical data. This null finding is theoretically notable and empirically revealing. It suggests that, in the context of Tehran, normative perceptions regarding environmentally responsible behavior are not significantly shaped by trust in governmental bodies, environmental agencies, or other formal institutions. While institutional actors are often assumed to possess the authority and legitimacy to set social expectations [44,72], this study indicates a disconnect between institutional credibility and normative influence. One potential interpretation is that institutional trust may be insufficiently internalized to affect perceived social expectations. Unlike interpersonal or media influence, which individuals encounter frequently and relationally, institutional messaging may appear distant, abstract, or politically neutral—thus failing to activate the kind of socially embedded pressure that forms subjective norms. This is particularly relevant in contexts where public skepticism toward institutions is high or where institutional communication lacks transparency, frequency, or emotional resonance. In practical terms, this implies that efforts by environmental institutions to foster pro-environmental behavior through normative appeals may fall short if not supported by more relational, culturally resonant, and trust-building communication strategies. Rather than relying solely on formal messaging, institutions could collaborate with local community leaders, civil society groups, or media influencers to bridge the gap between formal authority and perceived social expectation.

The results provide compelling evidence in support of Hypothesis 4, indicating that social identity has a strong and statistically significant positive effect on subjective norms. Among all the predictors examined, social identity emerged as the most influential determinant of perceived social pressure, highlighting the centrality of group-based self-conceptions in shaping environmental expectations. This finding aligns with foundational theories in social psychology, particularly social identity theory, which posits that individuals derive meaning, attitudes, and normative standards from the groups with which they identify [52,73]. In the environmental domain, group affiliation plays a dual role; it not only establishes behavioral norms but also instills a sense of obligation and belonging that strengthens compliance with those norms. Individuals who see themselves as part of a pro-environmental community are more likely to internalize the expectations of that group as personal obligations, which manifest as heightened subjective norms [53,74]. This process is especially potent in contexts where sustainability is framed as a shared group value or moral identity, reinforcing the emotional and social salience of normative cues. From a practical perspective, this insight underscores the strategic importance of fostering collective environmental identities. Campaigns that frame sustainability as a marker of group membership can enhance the effectiveness of normative messaging. Social identity also offers scalability; once a pro-environmental identity is activated, individuals are likely to seek consistency with group values across multiple behavioral domains.

The findings robustly confirm Hypothesis 5, demonstrating that subjective norms significantly influence personal norms. This relationship underscores an important psychological mechanism. Social expectations, when consistently perceived and salient, are often internalized as personal moral obligations [75,76]. In other words, what individuals believe others expect of them can gradually become what they expect of themselves [4]. The strength and significance of this path suggest that subjective norms function not only as direct predictors of behavior but also as catalysts for internal moral development. Individuals exposed to persistent normative pressures, whether through peers, media, or social groups, may experience cognitive dissonance if their behaviors or attitudes are misaligned with those expectations. To resolve this dissonance, they may adopt those external standards as intrinsic values [4], thus transforming perceived social obligations into personal ethical commitments. This psychological pathway enhances behavioral consistency and may explain why socially influenced intentions often persist even in the absence of external monitoring. Campaigns that aim to encourage sustainable behavior through social norms should also consider the long-term goal of internalization. Repeated exposure to normative messages in socially meaningful contexts can foster the moral internalization of environmental values. This, in turn, can create behavior, where individuals continue to act sustainably even in the absence of social prompts or incentives.

The result confirmed Hypothesis 6, indicating that subjective norms exert a significant and positive effect on pro-environmental behavioral intention. The magnitude of this effect reinforces the theoretical proposition that subjective norms are not peripheral or secondary factors but rather core motivational drivers within socially embedded behavioral processes. This finding is consistent with the foundational claims of the TPB [9], which identifies subjective norms as one of the three principal antecedents of intention. However, the model unpacks its antecedents, thereby enhancing explanatory precision. The significant direct path from subjective norms to intention, even after accounting for personal norms and other exogenous influences, suggests that social expectations retain independent motivational force, beyond what is internalized or morally endorsed. Importantly, the predictive strength of subjective norms in this context suggests that interventions leveraging social norms may yield significant behavioral shifts, particularly when targeting individuals embedded in dense social networks or communities with strong normative expectations [77,78]. This includes messaging strategies that emphasize peer behavior, public approval, or reputational outcomes, which are known to amplify normative salience. However, it also highlights the potential vulnerability of behavioral intentions to normative reversals; when social expectations change, intentions may follow suit unless they have been internalized as personal or moral imperatives. This positions subjective norms not only as a reactive force but also as an active, constructible resource in efforts to promote sustainable urban lifestyles.

The confirmation of Hypothesis 7 demonstrates that personal norms significantly and positively influence pro-environmental behavioral intention. This result affirms the psychological importance of internalized moral obligations in guiding environmentally responsible behavior [46,76]. Personal norms serve as powerful motivational anchors, especially when external pressures are absent or ambiguous. This finding also validates the model’s hypothesized mediated pathway, in which subjective norms indirectly influence behavioral intention through the formation of personal norms [75]. This transformation of external social cues into internalized ethical standards is a critical process in long-term behavioral change and resilience. Beyond their direct influence, the findings of this study also highlight the important mediating role of personal norms in the relationship between subjective norms and behavioral intention. The structural model confirmed that subjective norms significantly predict personal norms, which in turn exert a direct effect on pro-environmental intention. This suggests a partial mediation effect, wherein perceived social expectations not only influence behavior directly but also indirectly through the internalization of these expectations as personal moral obligations. This mediating pathway offers a more nuanced understanding of how social influence is transformed into enduring behavioral commitment. In practical terms, it implies that efforts to strengthen subjective norms may have amplified effects when they succeed in fostering moral reflection and personal ethical endorsement of pro-environmental actions. This internalization process may also explain the long-term persistence of behavior, even in the absence of external pressures. Thus, personal norms serve as a critical psychological mechanism that bridges external social cues and internal motivation, reinforcing the integrative power of the model and supporting its alignment with both the TPB and the NAM. From an applied standpoint, the significant contribution of personal norms to behavioral intention suggests that normative internalization should be a strategic goal of environmental interventions. Programs that merely induce compliance through social pressure or rule enforcement may achieve short-term outcomes but risk behavioral backsliding once the pressure subsides. In contrast, interventions that foster personal reflection, ethical engagement, and identity-based appeals are more likely to cultivate sustainable behaviors that persist over time.

4.1. Implications

4.1.1. Theoretical Implications

This study offers several important theoretical contributions to the literature on pro-environmental behavior, particularly in the context of urban green space engagement. First and foremost, it re-conceptualized subjective norms not as a static and exogenous variable, but as a socially constructed and dynamic outcome shaped by multiple antecedents. This reframing addresses long-standing critiques of behavioral models that emphasize the limited explanatory depth regarding how social norms are formed and why their effects vary across contexts. By integrating distinct sources of normative influence, the model enhances theoretical precision and captures the multidimensional origins of perceived social pressure. Second, this study introduces a critical mediational pathway by demonstrating that subjective norms significantly influence personal norms, which in turn affect behavioral intentions. The proposed mechanism bridges the TPB with the NAM and the VBN theory, both of which emphasize the role of internalized moral obligation in driving environmentally responsible behavior. According to NAM, personal norms and feelings of moral responsibility are activated when individuals are aware of the consequences of their actions and feel responsible for those consequences. The VBN theory extends this by linking environmental values, beliefs, and personal norms in a causal chain leading to pro-environmental action. While TPB focuses on rational, intention-based predictors of behavior such as attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms, it often underrepresents internal moral motivations. By proposing that subjective norms can be internalized and transformed into personal norms, this study highlights a key psychological process where perceived social pressure (a TPB component) may activate personal norms (as conceptualized in NAM and VBN). Thus, this study offers a theoretical bridge that connects external social influences with internal moral drivers of behavior, enriching our understanding of the motivational underpinnings of pro-environmental actions. The confirmation of this pathway supports a developmental understanding of motivation, in which external social expectations gradually transform into internalized ethical standards.

Third, the strong predictive role of social identity in shaping subjective norms represents a theoretically novel contribution. While identity constructs are emphasized in some models, few empirical studies have demonstrated that identity operates upstream of subjective norms. This finding implies that belonging to environmentally oriented groups amplifies individuals’ sensitivity to collective expectations, thereby strengthening perceived social norms. As such, this study highlights the structural role of identity processes in normative cognition. Fourth, the lack of a significant relationship between institutional trust and subjective norms challenges some of the assumptions embedded in environmental governance literature. While trust in institutions is often theorized as a facilitator of norm adoption and behavior change, the present study reveals that in certain socio-political contexts, institutional credibility may not translate into normative influence. This finding encourages future theoretical models to treat institutional trust as a context-dependent moderator rather than a universal antecedent of norm formation. Finally, the model’s explanatory power validates the utility of a socially enriched TPB framework for understanding pro-environmental behavior in urban ecosystems. This not only reinforces the value of expanding canonical theories with social–contextual variables but also supports the argument that normative processes are critical levers of intentional change, especially when they are conceptualized as emerging from diverse sources of social influence.

4.1.2. Policy and Managerial Implications

The findings of this study offer actionable insights for policymakers, urban planners, and managers of green infrastructure, especially within densely populated and environmentally stressed urban contexts such as Tehran. First, the strong influence of social identity on media influence suggests that interventions should go beyond information provision by fostering community-level environmental identities through media engagement. This can be achieved through initiatives such as neighborhood-based greening projects, co-managed community gardens, or local green citizen campaigns. These programs should be framed to emphasize collective belonging and shared environmental values, reinforcing pro-environmental behavior as a marker of local identity. In Tehran, where collectivist values and group affiliation are culturally salient, such efforts are likely to be particularly effective in mobilizing behavioral change. Second, the significant role of media influence indicates that communication strategies should leverage both mainstream and social media platforms to amplify environmental norms. Targeted media campaigns could use local influencers, neighborhood stories, and culturally relevant narratives to frame sustainable behaviors as both socially desirable and normative. This is especially important in Tehran, where access to green spaces varies by neighborhood, and digital communication plays an increasingly central role in shaping public discourse.

Third, interpersonal influence, including family, peers, and community members, remains a crucial channel for norm transmission. Urban managers and environmental NGOs should design peer-to-peer environmental education programs, youth ambassador networks, and family-inclusive events (such as eco-picnics or green competitions) in parks and forests. Such relational strategies may prove more impactful than impersonal institutional messaging, particularly in Tehran, where informal networks often carry greater trust and immediacy. Fourth, this study found that institutional trust did not significantly shape subjective norms. This calls into question the reliance on top-down public messaging as a standalone strategy. For addressing this issue, public authorities should build credibility by partnering with trusted intermediaries such as community leaders, local NGOs, or mosque networks to co-deliver environmental messages. Transparent, consistent engagement with local communities is needed to enhance the legitimacy of environmental governance and bridge the gap between policy and public perception. Finally, the demonstrated pathway from subjective norms to personal norms and behavioral intention highlights the importance of cultivating long-term internalization of pro-environmental values. Policymakers and educators should move beyond temporary awareness campaigns and invest in sustainability education embedded within formal school curricula, mosque-based environmental teachings, and public storytelling initiatives that evoke ethical responsibility. By combining external reinforcement (media, peer, group identity) with internal motivation (personal moral obligation), environmental policies in Tehran can generate deeper, more resilient behavioral change among urban residents. In sum, a one-size-fits-all or institution-centered approach is unlikely to succeed.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Trends

While the present study offers valuable insights into the normative and social predictors of pro-environmental intention, several limitations should be acknowledged to inform the interpretation of the results and guide future research efforts. One of the primary limitations of this study lies in its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to infer causal relationships between constructs. Future research should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to examine the stability and causality of the observed relationships and to capture potential shifts in norms and intentions across different time frames or in response to specific interventions. This study was conducted in a single metropolitan context, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or cultural settings. Social identity, media influence, and trust in institutions may function differently across countries, cultures, and governance systems. Comparative studies across diverse urban and rural contexts, or cross-cultural analyses, would offer a broader understanding of how contextual variables shape the formation of environmental norms and intentions.

All constructs in this study were measured using self-reported survey items, which are subject to common method bias, social desirability bias, and recall errors. Although efforts were made to ensure anonymity and reduce response bias, future studies could incorporate behavioral measures, observational data, or multi-informant approaches to triangulate findings and enhance the robustness of the results. While the model included key constructs, other potentially relevant factors were not examined. These may include emotional drivers, contextual constraints, economic variables, and digital engagement. Expanding the model to include such factors could provide a more holistic view of the mechanisms driving pro-environmental behavior. In light of this study’s findings and limitations, several future research directions are suggested. Scholars should explore how emerging forms of media impact normative perceptions and environmental behavior. Additionally, given the increasing urgency of climate change, future studies could investigate how crisis framing, risk perception, and ecological emotions interact with social and personal norms to shape behavior. There is also growing interest in integrating behavioral science with digital technologies to promote sustainable lifestyles. Finally, interdisciplinary approaches that combine insights from psychology, communication, urban planning, and environmental policy are essential to developing more effective and scalable interventions for environmental behavior change.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the social determinants of pro-environmental intentions, with a particular focus on the mediating role of subjective norms. Drawing on constructs such as social identity, media influence, interpersonal influence, personal norms, and institutional trust, the structural model provided a comprehensive understanding of how both external and internal drivers shape individuals’ behavioral intentions in the environmental domain. The findings revealed that subjective norms serve as a critical pathway through which social factors influence personal norms and behavioral intentions. Social identity emerged as the most influential predictor of subjective norms, followed by media and interpersonal influence. These results underscore the significance of social context in the formation of normative beliefs and highlight the importance of community belonging, media exposure, and peer interaction in shaping environmental attitudes. In contrast, institutional trust did not significantly affect subjective norms, suggesting that formal institutions may play a more indirect role in shaping behavior through other mechanisms such as policy design or service delivery. This study confirmed that both subjective and personal norms are essential determinants of pro-environmental intention, reaffirming the relevance of value-based and normative approaches in environmental behavior research. The model demonstrated strong explanatory power, accounting for substantial variance in both subjective norms and behavioral intentions. Despite its contributions, this study has limitations, including its cross-sectional design, single-city focus, and reliance on self-reported data. These limitations suggest the need for longitudinal, cross-cultural, and mixed-methods research to validate and extend the model. Future studies could also further examine the mediating role of personal norms and explore additional factors such as emotions or digital engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., K.M. and A.-F.H.; methodology, R.M.; software, R.M.; validation, K.M. and A.-F.H.; formal analysis, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M. and A.-F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available based on request from first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hong, W.; Ren, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, F.; Zhang, P.; Hong, S.; Ma, Z. Spatiotemporal Changes in Urban Forest Carbon Sequestration Capacity and Its Potential Drivers in an Urban Agglomeration: Implications for Urban CO2 Emission Mitigation under China’s Rapid Urbanization. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshyari, Z.; Maleknia, R.; Naghavi, H.; Barazmand, S. Studying Spatial Distribution of Urban Parks of Khoramabad City Using Network Analysis and Buffering Analysis. J. Wood For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 27, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, S.; Maleknia, R.; Azizi, R. Environmental Responsibility in Urban Forests: A Cognitive Analysis of Visitors’ Behavior. Forests 2024, 15, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Ren, J.; Cui, C.; Hou, Y.; Wen, Y. Do Value Orientations and Beliefs Play a Positive Role in Shaping Personal Norms for Urban Green Space Conservation? Land 2022, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taflinger, S.; Sattler, S. A Situational Test of the Health Belief Model: How Perceived Susceptibility Mediates the Effects of the Environment on Behavioral Intentions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 346, 116715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X. Organ Donation Information Scanning, Seeking, and Discussing: Impacts on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Donation Intentions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 365, 117543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar, A.; Akbar, M.; Poulova, P. Understanding the Drivers of a Pro-Environmental Attitude in Higher Education Institutions: The Interplay between Knowledge, Consciousness, and Social Influence. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 1458698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781136874734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, Y. Residents’ Support Intentions and Behaviors Regarding Urban Trees Programs: A Structural Equation Modeling-Multi Group Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 10020377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczuka, J.M.; Meinert, J.; Krämer, N.C. Listen to the Scientists: Effects of Exposure to Scientists and General Media Consumption on Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Mechanisms during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 8826396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Thuy, P.T.; Hue, N.T.; Dat, L.Q. Households’ Willingness-to-Pay for Mangrove Environmental Services: Evidence from Phu Long, Northeast Vietnam. Trees For. People 2024, 15, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleknia, R.; Azadi, H.; Ghahramani, A.; Deljouei, A.; Sadeghi, S.M.M. Urban Flood Mitigation and Peri-Urban Forest Management: A Study on Citizen Participation Intention. Forests 2024, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulazeem, H.M.; Meckawy, R.; Schwarz, S.; Novillo-Ortiz, D.; Klug, S.J. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Primary Care Physicians toward Clinical AI-Assisted Digital Health Technologies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 201, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Abdullahi, M.S.; Tanveer, M.I. Influence of Green Human Resource Management on Employee Green Behavior: The Sequential Mediating Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control and Attitude toward Corporate Environmental Policy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2514–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Tuyet, T.; Do, M.P.; Nguyen, N. The Effect of Sensation Seeking on Intention to Consume Street Food: Utilizing the Theory of Planned Behavior. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2460716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleknia, R.; Namdari, S. Generation Z and Climate Mitigation Initiatives: Understanding Intention to Join National Tree-Planting Projects. Trees For. People 2025, 19, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleknia, R.; Heindorf, C.; Rahimian, M.; Saadatmanesh, R. Do Generational Differences Determine the Conservation Intention and Behavior towards Sacred Trees? Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, M.A.; Rodoni, A.; Al Arif, M.N.R.; Hidayah, N. Intention to Participate in Islamic Banking in Indonesia: Does Socio-Political Identity Matter? J. Islam. Mark. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taso, Y.; Ho, C.; Chen, R. The Impact of Problem Awareness and Biospheric Values on the Intention to Use a Smart Meter. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häyrinen, L.; Kaseva, J.; Pouta, E. Finnish Forest Owners’ Intentions to Participate in Cooperative Forest Management. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 172, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Morais, S. Air Quality in Tehran, Iran: Spatio-Temporal Characteristics, Human Health Effects, Economic Costs and Recommendations for Good Practice. Atmos. Environ. X 2023, 19, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabizadeh, M.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Zarean, M.; Ahrari, S.; Ahmadi, A.R. Narratives of Resilience: Understanding Iranian Breast Cancer Survivors through Health Belief Model and Stress-Coping Theory for Enhanced Interventions. BMC Womens. Health 2024, 24, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wen, H.; Zhang, D.Y.; Yang, L.; Hong, X.C.; Wen, C. How Social Media Data Mirror Spatio-Temporal Behavioral Patterns of Tourists in Urban Forests: A Case Study of Kushan Scenic Area in Fuzhou, China. Forests 2024, 15, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöbel, M.; Rieskamp, J.; Huber, R. Social Influences in Sequential Decision Making. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Meng, P.; Chen, C. The Effects of Power and Social Norms on Power Decision Making. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, Beliefs, and Proenvironmental Action: Attitude Formation Toward Emergent Attitude Objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining Proenvironmental Intention and Behavior by Personal Norms and the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P. Descriptive Norms as an Additional Predictor in the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyza, P.; Cabelkova, I.; Pierański, B.; Malec, K.; Borusiak, B.; Smutka, L.; Nagy, S.; Gawel, A.; Bernardo López Lluch, D.; Kis, K.; et al. The Predictive Power of Environmental Concern, Perceived Behavioral Control and Social Norms in Shaping Pro-Environmental Intentions: A multicountry Study. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1289139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.; Sprecher, S. Interpersonal Influence. In Encyclopedia of Human Relationships; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.; Zheng, C.; Cho, D.; Kim, Y.; Dong, Q. The Impact of Interpersonal Interaction on Purchase Intention in Livestreaming E-Commerce: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Interpersonal Interaction on Consumers’ Purchase Intention under e-Commerce Live Broadcasting Mode: The Moderating Role of Presence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1097768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.C.; Yang, L.H. Exploring Antecedents of Passengers’ Behavioral Intentions toward Autonomous Buses: A Decomposed Planning Behavior Approach. J. Public Transp. 2025, 27, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Qu, H. The Influence of Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Platforms’ Green Marketing on Consumers’ pro-Environmental Behavioural Intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.P.; Eko, R.; Ong, L.; Paskuj, B.; Godfrey, A.; Garg, A.; Rea, H. Changing Minds about Climate Change in Indonesia through a TV Drama. Front. Commun. 2024, 9, 1366289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Chaudhary, R. Do Attitude and Subjective Norm Mediate the Relationship Between Social Media E-WOM and Green Purchase Intention? An Empirical Investigation Using PLS-SEM. Vikalpa J. Decis. Makers 2025, 50, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock Baskin, M.E.; Hart, T.A.; Bajaj, A.; Gerlich, R.N.; Drumheller, K.D.; Kinsky, E.S. Subjective Norms and Social Media: Predicting Ethical Perception and Consumer Intentions during a Secondary Crisis. Ethics Behav. 2023, 33, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P. Physicians ’ Acceptance of Electronic Medical Records Exchange: An Extension of the Decomposed TPB Model with Institutional Trust and Perceived Risk. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 84, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, P.; Du, J.; Diakit, D.; Abban, O.J.; Kouakou, E. A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Wang, F.; Sakurai, J.; Kitagawa, H. Willing or Not? Rural Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Ecosystem Conservation in Economically Underdeveloped Regions: A Case Study in China’s Qinling National Park. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Lin, W. Could Trust Narrow the Intention-behavior Gap in Eco-friendly Food Consumption? Evidence from China. Agribusiness 2025, 41, 260–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, M.; Marino, V.; Resciniti, R. Exploring the Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention of Generation Z in the Tourism Context: The Role of Injunctive Social Norms and Personal Norms. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 33, 1100–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, S.K.; Jose, A. Attitude and Subjective Norm as Personal Moral Obligation Mediated Predictors of Intention to Build Eco-Friendly House. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2019, 30, 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, T. Moral Norm and the Two-Component Theory of Planned Behavior Model in Predicting Knowledge Sharing Intention: A Role of Mediator Desire. Psychology 2015, 6, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ambo Radde, H.; Rachman, I.; Matsumoto, T. Trying to Decrease Food-Wasting Behavior with Combined Theory Plan Behavior, Value Belief Norm, and Norm Activation Model: A Behavioral Approach for Sustainable Development. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 7, 2025149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sui, D. Investigating College Students’ Green Food Consumption Intentions in China: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1404465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Kyrychenko, Y.; Rathje, S.; Collier, N.; van der Linden, S.; Roozenbeek, J. Generative Language Models Exhibit Social Identity Biases. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, J.; Bandelow, N.C. Social Identities, Emotions and Policy Preferences. Policy Politics 2025, 53, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, M.; Guidetti, M.; Bianchi, M.; Cavazza, N.; Caso, D. Enhancing Intentions to Reduce Meat Consumption: An Experiment Comparing the Role of Self- and Social pro-Environmental Identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 101, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Diehl, Y.; Weber, T.; van Deuren, C.; Mues, A.W.; Schmidt, P. Testing the Cross-Cultural Invariance of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour in Predicting Biodiversity-Conserving Behavioural Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 89, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]