Assessing Collaborative Management Practices for Sustainable Forest Fire Governance in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

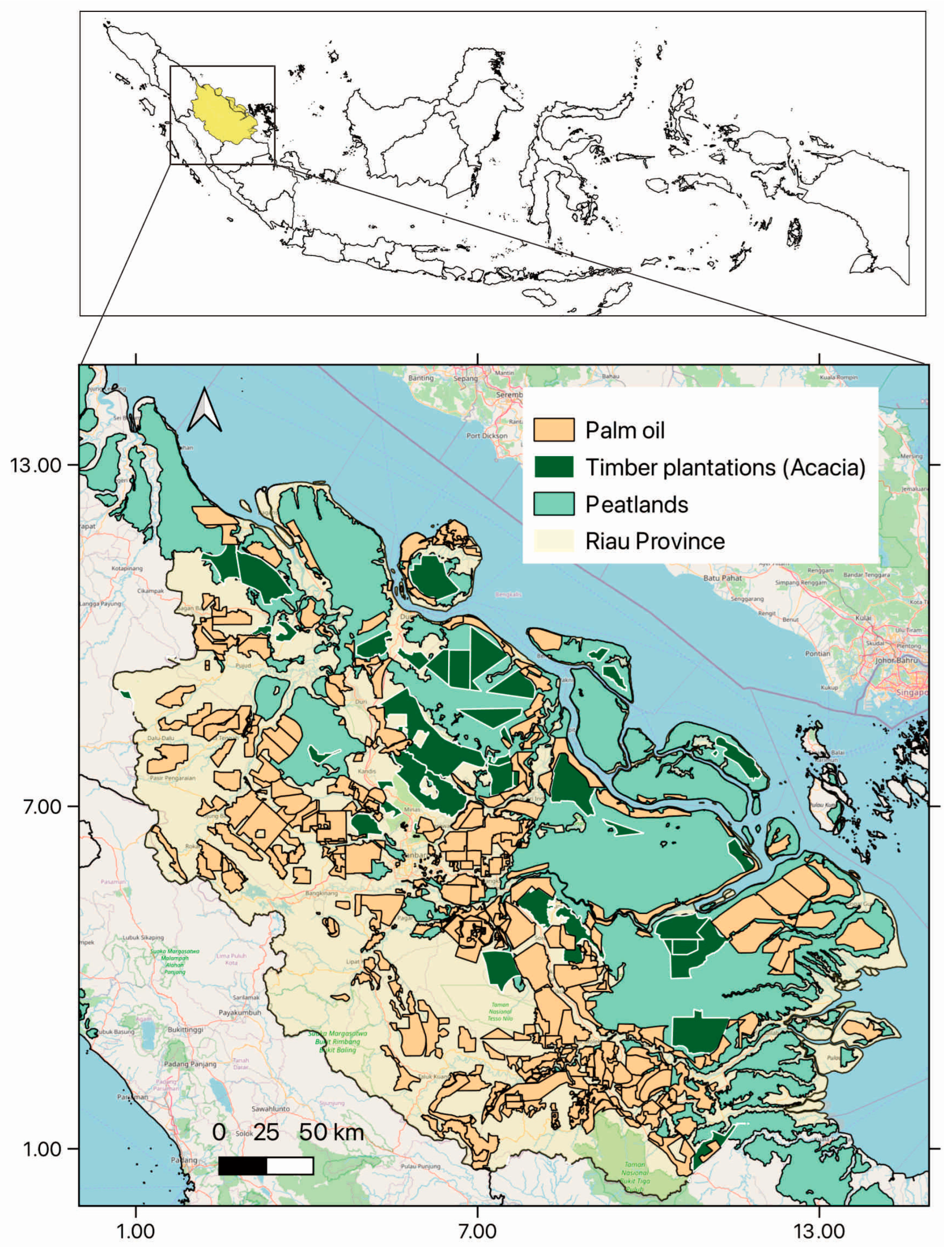

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

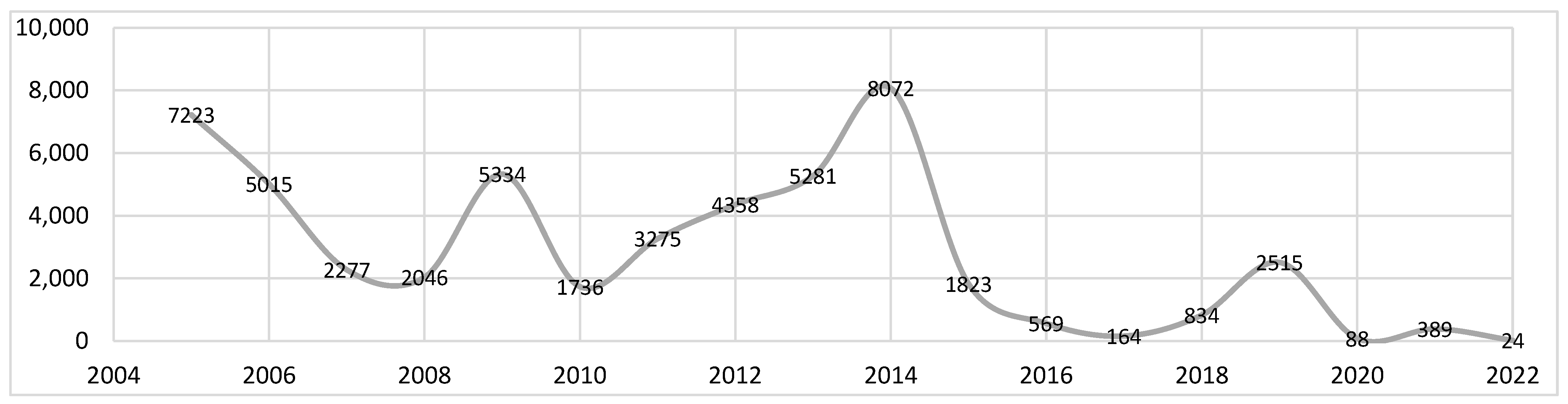

3.1. Forest Fire Management

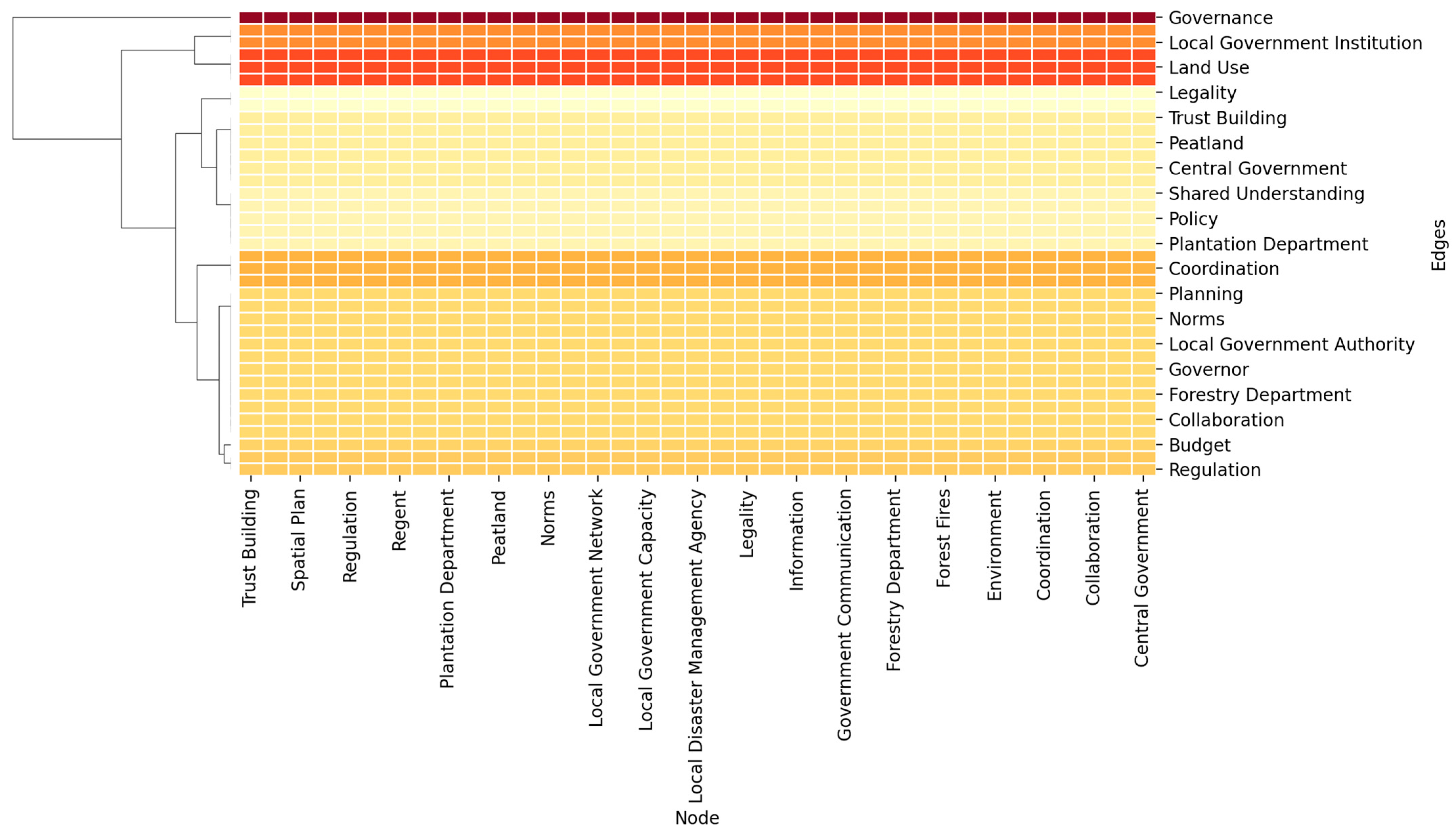

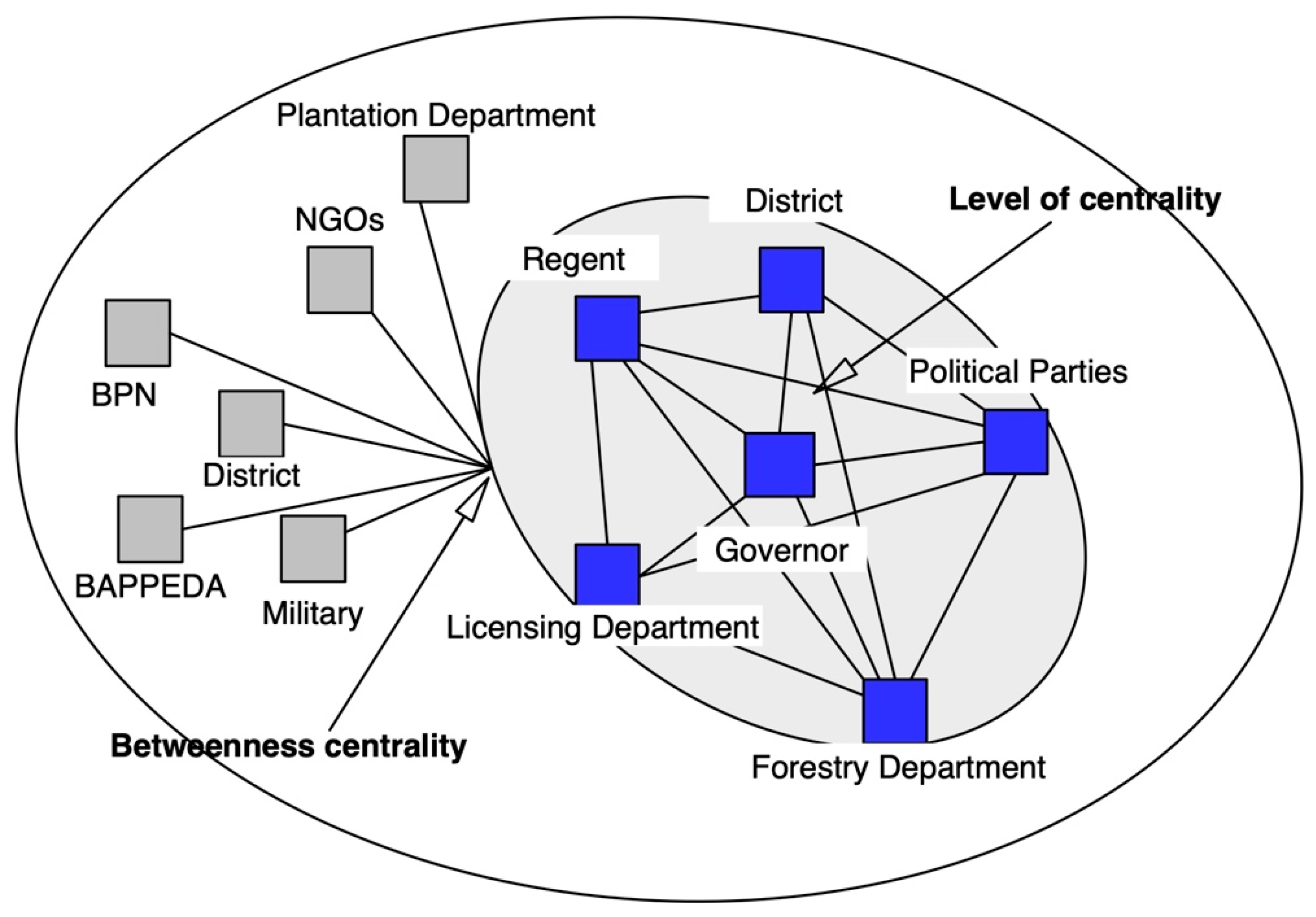

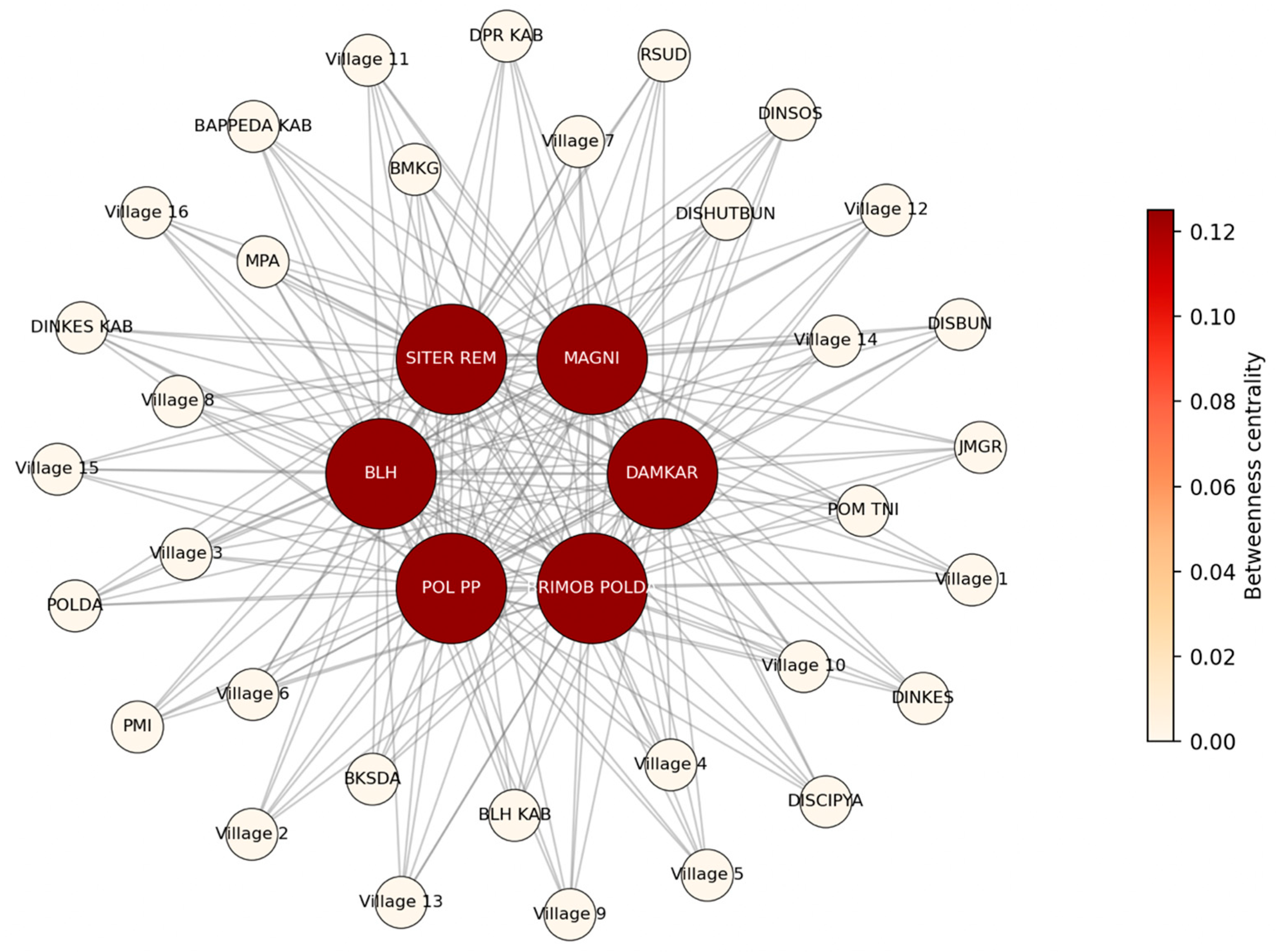

3.2. Collaboration and Social Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edwards, R.B.; Naylor, R.L.; Higgins, M.M.; Falcon, W.P. Causes of Indonesia’s Forest Fires. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhardi, E.F.; Handojo, H.N. Rehabilitation of Degraded Forests in Indonesia. World Bank Tech. Pap. 2016, 270, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.A.; Stephens, S.L. Fire and Sustainability: Considerations for California’s Altered Future Climate. Clim. Change 2008, 87, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Viegas, D.X.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Viegas, M.T.; Pita, L.P.; Rossa, C. Impacts of Fire on Society: Extreme Fire Propagation Issues. In Earth Observation of Wildland Fires in Mediterranean Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Hayes, D.J.; Fraver, S.; Chen, G. Global Pyrogenic Carbon Production During Recent Decades Has Created the Potential for a Large, Long–Term Sink of Atmospheric CO2. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 3682–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendana, M.; Idris, W.M.R.; Rahim, S.A.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Al Dughairi, A.A.; Albanai, J.A. Current and Future Land Fire Risk Mapping in the Southern Region of Sumatra, Indonesia, Using CMIP6 Data and GIS Analysis. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, C.C.; Chow, A.T.; Covino, T.P.; Fegel, T.S.; Pierson, D.N.; Rhea, A.E. The Legacy of a Severe Wildfire on Stream Nitrogen and Carbon in Headwater Catchments. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Prabhu, R.; McDougall, C. Adaptive Collaborative Management of Community Forests in Asia: Experiences from Nepal, Indonesia and the Philippines; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Bogor, Indonesia, 2007; ISBN 978-979-1412-37-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff, A.; Amacher, G.S.; Sills, E.O. Realistic REDD: Improving the Forest Impacts of Domestic Policies in Different Settings. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, E.P.; Ramdani, R.; Agustiyara; Nurmandi, A.; Trisnawati, D.W.; Fathani, A.T. Bureaucratic Inertia in Dealing with Annual Forest Fires in Indonesia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2021, 30, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.J.P.; Ford, R.M.; Keenan, R.J.; Larson, A.M. Learning through Practice? Learning from the REDD+ Demonstration Project, Kalimantan Forests and Climate Partnership (KFCP) in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulecka, J.; Obidzinski, K.; Dermawan, A. Corporate-Society Engagement in Plantation Forestry in Indonesia: Evolving Approaches and Their Implications. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwarno, A.; Nawir, A.A.; Julmansyah; Kurniawan. Participatory Modelling to Improve Partnership Schemes for Future Community-Based Forest Management in Sumbawa District, Indonesia. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A.S.; Achard, F.; Clayton, M.K.; Holmgren, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Tropical Forests Were the Primary Sources of New Agricultural Land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16732–16737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arfan, A. Managing the Impact of Smoke Haze Disaster: Response of Civil Society Groups Towards Jambi Provincial Government Performance. J. Bina Praja J. Home Aff. Gov. 2016, 8, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeliono, M.; Santoso, L.; Gallemore, C. REDD+ Policy Networks in Indonesia; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven, F.; Ehrenhard, M.; Kuhn, J. Open Government Objectives and Participation Motivations. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L. Collaboration Processes: Inside the Black Box. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternisko, A.; Cichocka, A.; Van Bavel, J.J. The Dark Side of Social Movements: Social Identity, Non-Conformity, and the Lure of Conspiracy Theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roengtam, S.; Agustiyara, A. Collaborative Governance for Forest Land Use Policy Implementation and Development. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2073670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigil, Z. Curbing Kurdish Ethno-Nationalism in Turkey: An Empirical Assessment of pro-Islamic and Socio-Economic Approaches. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2010, 33, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, L.J., Jr. Treating Networks Seriously: Practical and Research-Based Agendas in Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1997, 57, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainelli, R.; Toscano, P.; Gennaro, S.F.D.; Matese, A. Recent Advances in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Forest Remote Sensing—A Systematic Review. Part i: A General Framework. Forests 2021, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrianto, H.A.; Spracklen, D.V.; Arnold, S.R.; Sitanggang, I.S.; Syaufina, L. Forest and Land Fires Are Mainly Associated with Deforestation in Riau Province, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; ISBN 9781589010185. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, M. Visualizing Big Data: Social Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the Digital Research Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–12 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.C. The Development of Social Network Analysis; Empirical Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2004; Volume 27, ISBN 1594577145. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, R.; Toikka, A.; Primmer, E. Social Capital and Governance: A Social Network Analysis of Forest Biodiversity Collaboration in Central Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everton, S.F. Tracking, Destabilizing and Disrupting Dark Networks with Social Networks Analysis. Dark Networks Course Manual; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781107022591. [Google Scholar]

- Nagi, A.; Schroeder, M.; Kersten, W. Risk Management in Seaports: A Community Analysis at the Port of Hamburg. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, M.; Haikal, M.; Widyastuti, M.T.; Arif, C.; Santikayasa, I.P. The Impact of Rewetting Peatland on Fire Hazard in Riau, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossita, A.; Boer, R.; Hein, L.; Nurrochmat, D.; Riqqi, A. Peatland Fire Regime across Riau Peat Hydrological Unit, Indonesia. For. Soc. 2023, 7, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Forest Management: A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfatriani, F.; Darusman, D.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; Yustika, A.E.; Muttaqin, M.Z. Redesigning Indonesian Forest Fiscal Policy to Support Forest Conservation. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 61, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrici, A.M.; Hubacek, K. Challenges for REDD+ in Indonesia: A Case Study of Three Project Sites. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.; Vu, T.P.; Catacutan, D.; Nguyen, V.T. Governing Landscapes for Ecosystem Services: A Participatory Land-Use Scenario Development in the Northwest Montane Region of Vietnam. Environ. Manag. 2020, 68, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, H.R.; Yoshida, T.; Innes, J.L. A Collaborative Forest Management User Group’s Perceptions and Expectations on REDD + in Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, L.; Vayda, A.P. Slash and Burn and Fires in Indonesia: A Comment. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 56, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, F. Community Participation on Peat Restoration Policy for Forest Fire Rescue and Land in Sungai Tohor Village Meranti Island Riau Province Sumatra Indonesia. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2018, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, K.G.; Schwantes, A.; Gu, Y.; Kasibhatla, P.S. What Causes Deforestation in Indonesia? Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Ostrom, E. Collective Action, Property Rights, and Decentralization in Resource Use in India and Nepal. Polit. Soc. 2001, 14, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.G. Ethnonationalism as a Source of Stability in the Party Systems of Bulgaria and Romania: Minority Parties, Nationalism, and EU Membership. Natl. Ethn. Polit. 2016, 22, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbedomon, R.C.; Floquet, A.; Mongbo, R.; Salako, V.K.; Fandohan, A.B.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Kakaï, R.G. Socio-Economic and Ecological Outcomes of Community Based Forest Management: A Case Study from Tobé-Kpobidon Forest in Benin, Western Africa. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 64, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.J.; Wright, G.D.; Andersson, K.P. Local Politics of Forest Governance: Why NGO Support Can Reduce Local Government Responsiveness. World Dev. 2017, 92, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Cerciello, M.; Ferraro, A.; Garofalo, A. Spatial Analysis of Wildfire Incidence in the USA: The Role of Climatic Spillovers. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 6084–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathrin, B. Collaborative Governance in the Making: Implementation of a New Forest Management Regime in an Old-Growth Conflict Region of British Columbia, Canada. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Informant | List of Interviewees | Informants Number of Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Government organizations (provincial, regional, and district level) | Riau provincial environmental agency (BLH), regional planning agency (Bappeda), provincial legislative body (DPRD), forestry department, plantation department, provincial land agency and licensing/permitting department, district and sub-district leader. | 18 |

| Academics and local civil society representatives | Local universities, environmental forum (Majelis Lingkungan Hidup) linked to the Muhammadiyah organization. | 8 |

| NGOs | WWF Riau office, Jikalahari, Portal Hutan, and media and community environmental initiative. | 5 |

| Total | 31 |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Vertices | 47 |

| Unique edges | 296 |

| Diameter | 3 |

| Average distance | 1.68 |

| Graph density | 0.28 |

| SITER REM | Military command | BLH KAB | Environmental agency at regional level |

| DAMKAR | Firefighters | DISCIPYA | Spatial planning, human settlements |

| MAGNI | Fire control brigade under the Ministry of Forestry | DISHUTBUN | Forestry and plantation department |

| BRIMOB POLDA | Army special forces | DINKES | Health department |

| BLH | Environmental agency | DINSOS | Social service department |

| POL PP | The civil service police unit | RSUD | Regional public hospital |

| POM TNI | Military Police Command of Armed Force, Indonesia | NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| BMKG | Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysical Agency | BAPPEDA KAB | Regional development planning agency |

| BKSDA | Natural Resources Conservation Centre | MPA | Community fire awareness |

| JMGR | Riau Peatland Community Network | PMI | Indonesian Red Cross |

| KMPG | Community on peatland | DPR KAB | Regional people’s representative council |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roengtam, S.; Agustiyara, A. Assessing Collaborative Management Practices for Sustainable Forest Fire Governance in Indonesia. Forests 2025, 16, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071072

Roengtam S, Agustiyara A. Assessing Collaborative Management Practices for Sustainable Forest Fire Governance in Indonesia. Forests. 2025; 16(7):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071072

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoengtam, Sataporn, and Agustiyara Agustiyara. 2025. "Assessing Collaborative Management Practices for Sustainable Forest Fire Governance in Indonesia" Forests 16, no. 7: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071072

APA StyleRoengtam, S., & Agustiyara, A. (2025). Assessing Collaborative Management Practices for Sustainable Forest Fire Governance in Indonesia. Forests, 16(7), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071072