1. Introduction

The financial sector is the cornerstone of the modern economy. In China, the credit-based financial system—dominated by banks—has long occupied a central role. The banking sector accounts for approximately 90% of the financial sector’s total assets and profits [

1]. Consequently, the stable and sustainable development of the banking sector may nourish the real economy [

2]. Since the 1980s, developed economies have experienced a structural shift in capital accumulation from the real economy sectors to the financial sector [

3], accompanied by a substantial increase in the profit and wage shares of the financial sector [

4,

5]. In recent years, China’s economy has also encountered risks of de-industrialization and a shift towards a virtual economy [

6]. The profit distribution between the banking sector and real economy sectors exhibit asymmetrical characteristics. In China’s A-share market in 2024, the banking sector accounted for four of the top ten companies by market value and five of the top ten by net profit. Despite constituting less than 1% of all A-share listed companies, the banking sector accounts for over 40% of total net profits [

7]. In 2023, the return on equity of commercial banks stood at 8.93%, while that of industrial enterprises above designated size was only 4.82%. The vast majority of enterprises meet their operational funding needs through bank loans rather than the stock market or bond market. By using Chinese empirical data, an evaluation of the BSPs’ impacts on other sectors’ development offers valuable global insights for designing effective financial concession policies.

According to the concept of “production-finance profit-sharing” [

8], BSP ultimately originates from the value created in the real economy sectors. After the subprime mortgage crisis, the theory of monetary neutrality in classical economics has been challenged. Scholars began recognizing the asymmetric relationship between financial development and economic growth, leading to the “excessive financialization hypothesis” [

9,

10,

11]. As a financial intermediary, the banking sector does not directly create value. The excessive profits of the banking sector may reflect elevated financing costs for the real economy sectors, which potentially undermine their competitive advantage [

12]. In 2023, the profit margin on sales of enterprises above designated size in China’s wood processing, furniture manufacturing, and paper and paper products industries were 5.11%, 5.99%, and 3.91%, respectively. Rising interest burdens and financial expenses may significantly hinder these sectors’ development and export expansion. According to the new-new trade theory, firms that want to enter international markets should bear substantial fixed and startup costs, including establishing sales networks and advertising expenditures. It is assumed that a portion of firms’ fixed trade costs must be financed through credit [

13]. Inflation in regional BSPs may lead wood product manufacturing enterprises to face financing constraints characterized by limited access to credit and high borrowing costs, which hinder their ability to expand into new international markets or increase sales in existing ones. Additionally, financial pressure may restrict investment in product development and quality improvement, thereby constraining the export growth of wood products.

Changes in wood product exports of a country can result from variations in export volume or product variety. The ternary margins framework captures these dynamics through three components: the extensive margin (number of product types in established export markets), the quantity margin (export volume), and the price margin (export price). These margins reflect product innovation, the scale of existing exports, product quality, and shifts in competitive strategies [

14], which offers a comprehensive perspective on export growth patterns and underlying drivers on exporting. A growing body of empirical literature has examined the relationship between banking sector competition, financial development, and export margins, exploring the roles of financial development [

15], digital finance [

16], financial agglomeration [

17], banking fintech [

18], and green finance [

19]. Some studies have examined the sources of financial sector profits and the economic consequences of their excessive expansion [

20,

21]. However, there remains a paucity of research on the trade effects of regional variations in BSP, particularly their impacts on ternary margins of specific industries’ exports. As exports constitute a critical pillar of economic development worldwide, addressing this gap is essential. Insights from such research can provide valuable guidance for policymaking. Furthermore, factors such as the density of regional banking outlets, the development of digital finance, and other elements of financial infrastructure may moderate the relationship between BSPs and export performance. However, these moderating effects are seldom explored in the existing literature. In particular, the differential impacts of financial institution development in rural versus urban areas on export margins have received little scholarly attention. Notably, China implemented a large-scale “financial concession” policy between 2020 and 2022, including CNY 1.5 trillion in financial relief to the real economy in 2020, which is essentially a form of banking sector concession. However, empirical evaluations of trade effects from this policy remain scarce, which highlights the need for further investigation.

In conclusion, China’s economy is increasingly at risk of excessive financialization, while the WFP manufacturing industry has been always characterized by low profit margins and being highly sensitive to financial costs. This study utilizes a comprehensive dataset on the ternary margins of WFP exports from 31 Chinese provinces to 184 countries. It constructs provincial-level indicators of BSP to assess its impact on these export margins by using Stata (version 14.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). In addition, this study investigates the moderating roles of provincial financial infrastructure. The marginal contributions of this research are threefold. First, drawing on the theoretical framework of profit sharing between the banking sector and the real economy, this study reveals how profitability influences the extensive, quantity, and price margins of wood product exports. A large body of the literature studies the relationship between financial development, “difficult financing and expensive credit”, exports, and export margins. However, the literature on BSP and its trade effects is rare. This study fills the gap, which offers more precise and reliable empirical evidence for the “financial over-development hypothesis”. Second, it further explores the moderating effects of the number of bank institution outlets, the proportion of rural bank institution outlets, and the development of digital finance. It identifies the enabling effects of financial institution distribution, regional balance, and the synergy between traditional and new financial development. Compared with impacting path studies, this is more useful for improving financial policies to mitigate the negative effects of banking profit inflation on industry export expansion. Third, this study distinguishes between periods before and after China’s financial concession policy and finds that the policy can eliminate BSPs’ negative effects. The results provides micro-level evidence for countries worldwide to implement financial concession policies to support real economic development.

2. Literature Review

The extant literature on finance–economic development linkages has significantly advanced our understanding of financial factors in driving economic growth and trade. However, notable gaps persist. First, while prior studies highlight how financial development enhances exports, limited research has examined how regional variations in banking profitability distinctively influence export profit margins across individual industries. Second, scant attention has been given to the synergistic effects of traditional and emerging finance on export growth or the differing impacts of rural–urban financial institution development disparities on export profitability. Third, the trade-related implications of banking profits and their role in shaping export margins remain underexplored. This study bridges these gaps by analyzing China’s foreign-owned enterprise sector, offering deeper insights into financial-trade interactions and delivering empirical evidence on the trade effects of regional bank-specific profitability.

2.1. Regional Financial Development and Exports

The relationship between financial development and export trade has consistently drawn scholarly interest. Early research primarily investigated the impact of traditional finance on exports. For instance, Berman and Hericourt [

22] noted that enhanced financial development in a country effectively mitigates the disconnect between productivity and export decisions, thereby fostering the growth of exporting firms. Tie et al. [

15] highlighted that in scenarios of high corporate financial fragility, local financial development stabilizes export relationships and exerts a positive influence on the quantity and quality of exports [

17], thereby encouraging corporate participation in export activities [

23]. As the financial sector continues to evolve, academic attention has gradually shifted toward the effects of financial technology advancements and emerging finance on exports. Li et al. [

18] discovered that the development of fintech in the banking industry facilitates private enterprise exports and provides alternative funding sources for financially vulnerable industries, thereby supporting their export activities [

24]. Furthermore, Tao and Cai [

16], Li [

25], and others have demonstrated that the growth of digital inclusive finance significantly enhances the expansion of export comparative advantages and export scale. Additionally, the expansion of small and medium-sized banks markedly strengthens firms’ export propensity and scale [

26]. The increase in foreign banks from importing countries also promotes local firms’ entry into export markets, diversifies export product categories, and boosts initial sales [

27].

While prior studies have confirmed the positive impact of traditional and emerging finance on export trade from various perspectives, existing research still has certain limitations. First, few studies have explored whether there is a synergistic effect between traditional and emerging finance in promoting export growth. Second, macro-level measurements of regional financial development often fail to adequately distinguish the trade effects and differences in the development of various types of financial institutions. Additionally, although some research has focused on export trade and the urban–rural distribution differences based on financial institutions, most studies have concentrated on either rural or urban areas, neglecting the fact that the service efficiency of different types of financial institutions varies across specific industries.

2.2. Regional Financial Development and Export Margins

The influence of financial development on export trade is becoming increasingly evident across various fields and levels. At the industry level, some researchers have indicated that regional financial development significantly benefits industries with high external financing dependency and low asset collateral ratios, enhancing their export profit margins [

28,

29,

30]. This impact is also observed at the micro-enterprise level, suggesting that financial development universally boosts enterprises’ export profit margins [

31]. Chen and others discovered that commercial and bank credit considerably promote the extensive and intensive profit margins of enterprise exports [

32]. Jin and others [

19] confirms that improving financial scale, structure, and efficiency effectively drives the growth of China’s export binary margin. Moreover, green finance has demonstrated unique advantages by significantly increasing the intensity and wide margin of export trade [

19].

In the emerging financial sector, the emergence of digital and internet finance has positively affected export trade. They not only facilitate the expansion of the export binary margin [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] but also provide new financing channels and development models, which further optimizes enterprises’ export structure and efficiency [

38].

Conversely, external financing shocks, such as financial crises, have drawn significant attention for their impact on trade. Paravisini et al. found that during the 2008 financial crisis, reduced bank credit supply caused corporate financing difficulties, thereby decreasing the intensive margin of corporate exports [

39]. Similarly, Gong et al.’s research shows that banking crises reduce the number of companies entering the market, lower export market concentration, and slow down the dynamics of product and destination markets [

40]. Additionally, financial factors like interest rate shocks, P2P loan crises, and extension restrictions have been proven to negatively affect the intensive and extensive profit margins of enterprises [

41,

42,

43].

The above literature generally confirms the positive effects of traditional and emerging finance on regional, industry, and firm export margins. Similarly, little literature explores the synergistic effects of traditional and emerging finance or examines the impact and differences of financial institution development, focusing on rural or urban areas, on export margins. Additionally, the above literature rarely uses the growth in financial institution outlets to measure local financial development levels. It cannot test the trade effects of increased financial institution outlets.

2.3. Financial Sector Profits and Economic Effects

The relationship between financial development and economic growth has consistently drawn significant attention in academic and policy circles. Wen et al. [

6] innovatively integrated Marx’s theory of productive capital with Western economic growth theory, incorporating Marx’s classic notion of “surplus value originates from profit” into the modern economic growth framework. Through theoretical analysis and empirical research, they identified an inverted U-shaped nonlinear relationship between financial sector profits and economic growth. This indicates that financial sector profit growth initially promotes economic expansion but, once a critical threshold is exceeded, its positive impact on economic growth diminishes or even turns negative. This conclusion has garnered further support from other scholars. Khatiwada [

20], Luo, and Zu [

44] highlighted that excessive financial sector profit expansion reduces the share of industrial investment, thereby undermining the real economy [

45]. Wen et al. [

46] also uncovered a significant negative correlation between the financial sector’s profit ratio and economic growth rate in the Chinese context. Similarly, Smith et al. [

47] conducted an empirical study using European banks as a sample, revealing that excessive bank profits weaken the driving force of economic growth. Furthermore, the economic effects of financial sector profits exhibit significant nonlinear characteristics. Lin et al. [

1] observed a typical U-shaped relationship between the Financial Stability Plan and the development of the real economy, indicating that BSPs’ impact on the real economy differs in its early and later implementation stages. However, He et al. [

48] confirmed an inverted U-shaped relationship, further underscoring the complex nonlinear interplay between financial sector profits and economic growth. Additionally, Mou et al. [

49] demonstrated that urban financial sector profits have a nonlinear effect on total factor productivity, further elucidating the intricate mechanisms through which financial factors influence economic efficiency.

At the policy level, on 22 February 2019, the China Banking Association issued an initiative designed to reduce fees and provide financial incentives, thereby better supporting the development of the real economy. Subsequently, in 2020, the Chinese government introduced a series of financial preferential policies. The current literature predominantly examines the economic effects of these financial preferential policies. Markwei et al.’s simulation study shows that such policies have a significant investment promotion effect: they can increase the disposable income of institutional sectors and promote the expansion of consumer demand [

21].

However, existing research has largely overlooked the trade effects of financial preferential policies. In particular, studies on how these policies influence the export profit margins of regions, industries, and firms remain understudied. Considering that these policies aim to address enterprises’ financing difficulties and high financing costs, their impact on export profit margins merits further investigation. Although the effect of financial sector profits on economic growth is widely acknowledged, research on the trade effects of financial preferential policies and their potential impact on export profit margins remains relatively limited. This area thus presents crucial directions for future research and aids in achieving a more comprehensive understanding of financial policies’ role in promoting economic growth and trade development.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Analysis of BSPs’ Effects

Post-Keynesian economists, such as Robert Pollin and Till van Treeck, argue that financial profits are derived from the redistribution of current real national income flows—namely, profits and wages. In Marx’s theory of interest and profit sharing, money capitalists transfer control over loan capital to industrial capitalists and, in return, are entitled to a portion of the profits or surplus value generated by the latter [

6,

8]. Accordingly, BSP originates from industrial profits, reflecting the new value created by labor in the production process. Scholars such as Lapavitsas [

50] and Levina [

51] have advanced the theory of financial predation, which posits that the essence of financial profits lies in surplus value extraction and profit transfers. Meanwhile, researchers including Foley [

52], Norfield [

53], Fine [

54], and Mavroudeas [

55] uphold Marx’s labor theory of value, asserting that surplus value is the sole source of financial profits. In conclusion, the banking sector cannot directly create new value but has indirect value and the “quality” rationale of sharing industrial profits. However, excessive inflation of BSPs can hinder industrial development. This is why the theory of money neutrality was widely questioned after the subprime mortgage crisis, and the negative effects of financial sector profit inflation have been extensively studied [

56], such as the “financial over-development hypothesis” [

57,

58]. When financial capital allocated to the real economy achieves excessively high returns, it triggers the problem of “difficult financing and expensive credit” for the real economy. This implies high costs for real economy sectors, which may lead to the outflow of industrial capital and harm the development of real sectors.

Classical and new-new trade theories posit that a firm from country A can access export markets if it offers a lower export price than competitors, implying that low prices are rooted in low production costs. Many low-quality WFPs—such as particleboard and standard cardboard—exhibit characteristics similar to homogeneous goods. As a result, Chinese exporters often rely on low-price competition strategies in international markets. According to official data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the cost-to-income ratios—calculated as (operating costs + selling expenses + administrative expenses + financial expenses)/operating income × 100%—for large-scale industrial enterprises in the wood processing, furniture manufacturing, and paper and paper products industries in 2023 were 94.43%, 94.68%, and 96.73%, respectively. The above data indicate that manufacturing costs for WFP enterprises in China remain high, and the sensitivity of profits to changes in financial expenses is pronounced. When regional BSPs decline, a greater share of profits is redistributed to the real economy, reducing the likelihood that local wood product manufacturers will encounter financing difficulties or elevated borrowing costs. As a result, firms are more likely to access low-cost credit to support export market expansion (extensive margin), build international distribution channels to scale up existing exports (intensive margin), and invest in product quality improvement. Moreover, these enterprises are better positioned under favorable financing conditions to diversify their export portfolios within existing markets, leveraging cost advantages and product differentiation to enhance their extensive margins. Over 80% of wood processing enterprises in China are private enterprises. High BSPs may hinder private enterprises from obtaining the low-cost funds needed for export expansion. When BSPs exceed a reasonable level, limited credit resources in the real economy will concentrate on state-owned enterprises, crowding credit lines for private wood processing enterprises.

Moreover, most wood processing enterprises are located in remote areas, have limited industrial land ownership, and have low financial data transparency, making it difficult to obtain funds from the formal financial system. High regional BSPs may compel wood processing enterprises to seek financing through shadow banking and private lending channels, which often involve significantly higher borrowing costs. This shift increases financial burdens and reduces formal credit accessibility. Studies have found that the effective interest rates for small wood enterprises borrowing from banks range from 15% to 25%. In comparison, rates from shadow banking sources can reach 20% to 40% (research on coordination mechanisms of financial–real economy sector). Such “difficult and expensive financing” conditions, driven by elevated BSPs, may reduce firms’ willingness to engage in international market development and limit their capacity to export. In turn, this erodes the price competitiveness of existing export products, weakens firms’ international market positioning, and ultimately constrains the export expansion of wood processing enterprises. Furthermore, high BSPs reflect its dominant position in credit resource allocation, allowing it to freely direct resources to higher-profit industries. This leads to other production factors directed toward higher-profit industries, creating a spiral that mutually drives up BSPs. As mentioned, China’s wood processing enterprises are generally in low-profit industries. This intensifies the exit of more credit resources from this industry, creating a larger “crowding-out effect”, hindering export expansion through the extensive and intensive margin. In summary, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Hypothesis 1. The profit level of the banking sector hurts the export margins of regional wood processing industries.

3.2. Theoretical Analysis of Moderating Effects

The theory of the geographical structure of financial supply argues that the mobility of capital in geographical space is limited [

59]. Most wood processing enterprises are located in the main raw material production areas, far from banking and financial institutions. An increase in bank institution outlets and their geographic spread shortens the distance between banking institutions and wood processing enterprises. This helps resolve the “spatial price discrimination” of banking institutions and reduces transaction costs, thereby reducing enterprises’ capital costs. The “geographic pull-in effect” of an increase in county-level bank institution outlets reduces the cost for banking institutions to collect soft information, such as enterprises’ business capabilities and development prospects. When regional BSPs decline, in regions with a higher number and density of bank institution outlets, the cost-saving and geographic pull-in effects are more pronounced. At this point, banking institutions are more likely to maintain operational efficiency and effectiveness, continuing to provide high-quality credit services to wood processing enterprises for export expansion. Furthermore, since wood processing enterprises are mostly in non-urban areas, while banking institutions tend to be in urban districts, this asymmetry may limit the accessibility and cost of credit for wood processing enterprises. According to the theory of financial exclusion, the traditional financial system often overlooks economically underdeveloped rural areas to maximize shareholder profits. Therefore, the higher the proportion of rural bank institution outlets focused on rural areas, the more likely wood processing enterprises are to access credit services from formal financial institutions, and the more likely they are to meet the funding requirements for export expansion. In summary, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are proposed:

Hypothesis 2. An increase in the number of regional bank institution outlets can weaken the negative effects of BSP.

Hypothesis 3. An increase in the proportion of regional rural bank institution outlets can weaken the negative effects of BSP.

When regional BSP declines due to market demand and policy requirements, emerging digital finance may help banking institutions reduce transaction costs and overcome the geographic limitations of financial services. This could become a valuable supplement to traditional banking institutions, helping more high-quality wood processing enterprises secure funding to develop export products and build overseas sales networks. In other words, digital finance has the potential to alleviate the shortage of financial services after a decline in BSP. Digital credit is a key component or manifestation of digital finance, reshaping traditional banking institutions’ market orientation and internal service models [

60,

61], matching credit resources in a peer-to-peer manner, and alleviating the financing constraints faced by enterprises. The more mature the development of regional digital credit, the more likely it is to provide inclusive working capital for marginalized wood processing enterprises [

62], strengthening the price advantage of export products, helping firms overcome the fixed costs of initial exports, and continuing to develop new markets or expand the sales scale of existing products [

63]. In summary, Hypothesis 4 is proposed:

Hypothesis 4. Regional digital finance development can weaken the negative effects of BSP.

4. Research Design

4.1. Basic Econometric Model

To address the research questions posed in this study, we designed a comprehensive empirical analysis framework. First, we proposed four hypotheses based on the theoretical framework and literature review. Second, we designed a comprehensive research methodology, including the selection of variables, data sources, and econometric models, to test these hypotheses. Third, we conducted a series of empirical analyses, including baseline regression, robustness tests, heterogeneity tests, and moderating effect analyses, to verify the hypotheses from multiple perspectives.

This paper incorporates BSP into the analytical framework for the export margins of WFPs. However, the dataset covers both cross-sectional and time-series data from 31 provinces in mainland China for the years 2007–2022. However, this study examines the annual export margins of each province to 184 countries, and a three-dimensional panel dataset has been structured by year, province, and importing country. This leads to the issue that the province ID cannot satisfy uniqueness when using fixed and random effects panel models. Therefore, after stacking the data, ordinary least squares (OLS) are used for cross-sectional regression, a mixed model in panel data analysis. The regression econometric model is specified as follows:

In Equation (1), i, j, t represent the province, importing country, and year, respectively. The dependent variable Yijt represents the set of export margins of WFPs, which includes EMijt, IMijt, Qijt, and Pijt, denoting the extensive margin, intensive margin, quantity margin, and price margin of WFPs exported by province i to country j in year t. The core explanatory variable BSPit is the BSP of province i in year t. Xijt represents the collection of control variables. To mitigate internal correlation issues, fixed effects are applied to year (υt), province (μi), and importing country (ωj).

4.2. Selection and Description of Indicators

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

Export margins of WFPs (EMijt, IMijt, Qijt, and Pijt). This study integrates provincial-level WFP trade data into the global market framework. Firstly, bilateral 6-digit HS code data for WFP imports and exports are collected and organized from the United Nations trade database for all countries. Then, similar bilateral data at the provincial level for imports and exports from various countries are collected and organized from the China Customs database. Finally, the data from the United Nations trade database and the China Customs database are merged, excluding national-level data for China to prevent duplication. This process results in a comprehensive bilateral data source on WFPs with 6-digit codes for all Chinese provinces. This process seamlessly integrates the 6-digit HS code import and export data for WFPs from Chinese provinces into the global market, facilitating subsequent decomposition into ternary margins.

This paper adopts the ternary margin decomposition method and extends it from the national to the provincial level. Utilizing global bilateral 6-digit HS code data on WFPs, covering all Chinese provinces, this study decomposes the ternary margins of WFP exports from each province to its trading partner countries based on this data source.

The extensive margin is defined as follows:

The intensive margin is defined as follows:

In Equations (2) and (3), EMijt represents the overlap of the same product categories of WFPs exported from Chinese province i to importing country j in year t, which is known as the extensive margin. IMij denotes the proportionate share of exports from Chinese province i relative to the total world exports to importing country j among the same goods in year t, which is referred to as the intensive margin. Here, i, j, r represent the exporting country (Chinese provinces), importing country (trade partner countries), and reference country (world). Prtn and Xrtn denote the price and quantity of WFPs exported by the world to importing country j in product n in year t. Pijn and Xijn represent the price and quantity of WFPs exported from Chinese province i to importing country j in year t; Irjt represents the categories of WFPs exported by the world to importing country j in year t. Iijt represents the categories of WFPs exported from Chinese provinces i to importing country j in year t.

To further decompose the intensive margin, the specific formula is shown below:

In Equation (4),

Qijt represents the proportion of WFP categories that overlap in the same export market in year

t, where Chinese provinces i account for the world’s exports to import country

j in terms of quantity. A larger value indicates that the provinces of China export more WFPs than the global market, representing the quantity margin.

Pijt represents the proportion of WFPs categories that overlap in the same export market in year t, where Chinese provinces

i account for the world’s exports to import country

j in terms of price. A larger value indicates that the provinces of China command higher prices for their exported WFPs compared with the global market, representing the price margin. The calculation method for the weight w

ijtn is as shown in the formula:

In Equation (6), sijtn represents the share of the export value of the n type of product exported by Chinese province i to importing country j, relative to the total export value of WFPs from that province. srjn represents the share of the export value of the n type of product exported globally to importing country j, relative to the total export value of WFPs to that country.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

Currently, variables used to measure financial sector profits include the proportion of financial value-added to national income [

6], the proportion of financial value-added to the profits of industrial enterprises above a certain scale [

48], the ratio of total financial sector profits to the total profits of industrial enterprises [

49], and the return on total assets of the financial sector [

46]. Some scholars use BSPs as a representation of financial sector profits. The ratio of banking sector net profit to regional industrial value-added, return on equity in the banking sector [

1], and the return on total assets in the banking sector [

6] are commonly used. The income of Chinese banks includes net interest income, net fee and commission income, and other net income. The most relevant to the financing costs of wood processing enterprises are net interest income (interest income minus interest expenses) and net fee and commission income, which account for over 90% of total banking sector income [

64]. These are two key aspects of the China’s “financial concession” policy. The greater the two types of income, especially the larger the interest margin, the stronger the banking sector’s control over credit resources, resulting in higher financing costs for real economy sectors such as the wood processing industry. In summary, this study chooses the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) to total assets to measure the profitability of each bank within a provincial jurisdiction. It calculates the weighted average by multiplying the share of each bank’s operating income in the province’s total banking sector operating income by their respective profit levels. This average is considered the observation of the provincial BSP. The larger the value of this indicator, the higher the BSP level, and the higher the level of profit sharing with the real economy sectors.

It is worth noting that most commercial banks in China operate across regions. The profit statement of a commercial bank’s headquarters only summarizes and reports the total profit for the year without breaking it down by region. Therefore, reasonably allocating a commercial bank’s total profit to different provinces is the key to constructing the indicator. This paper assumes that the location selection of commercial bank outlets is rational after fully considering costs and benefits. Some studies suggest that commercial banks tend to establish outlets in areas where they can obtain high profits [

65]. The equilibrium eventually reached is that the profits of the commercial bank’s outlets in different provinces tend to converge. If the profits of outlets in different regions are not the same, the commercial bank will withdraw from low-profit areas and open new outlets in high-profit areas [

2]. In summary, the measurement variables designed in this paper are based on practical considerations and scientific reasoning.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Based on similar studies by Zhang and Liu [

66], Jin et al. [

19], Yang and Zhu [

67], and Tong et al. [

68], this paper selects the following control variables: (1) Exchange rate (

Exchange) represents the nominal exchange rate between the Chinese yuan and the currency of the export destination country

k in period

t. (2) The informatization level in a province (

IT) is measured by the ratio of the total value of postal and telecommunications services to the regional GDP. (3) The development level of the technology market in a province (

Tech) is measured by the ratio of the total transaction value of the technology market to the GDP. (4) Government intervention in a province (

Gov) is measured as the ratio of R&D fiscal expenditure to the GDP in each province. (5) The degree of openness in a province (

Open) is measured as the ratio of import and export trade volumes to the regional GDP. (6) The output of the province’s forestry industry (

Output) is measured as the logarithmic value of the sum of the total industrial output value of the wood processing industry, furniture manufacturing, and paper and paper products industries. (7) Geographical location (

Location) is assigned a value of 3 for eastern provinces, 2 for central provinces, and 1 for western provinces.

4.2.4. Sample Selection and Data Sources

As the most fundamental wood product, logs serve as the core raw material upstream of the forestry industry and are widely used in producing various forest-based processing products. Price fluctuations in logs affect the entire industry chain. Therefore, using log price fluctuations to reflect timber price volatility can provide a comprehensive measure of the cost pressures and market uncertainties affecting WFPs’ exports. Based on references such as the China Forestry Development Report and the China Customs Statistical Yearbook, HS4403 is the standard for logs, with imported log price fluctuations used to gauge timber price volatility. At the same time, due to constraints from natural forest conservation policies and ecological public welfare forest policies, the export proportion of China’s resource-based WFPs is extremely low. Thus, this paper primarily defines exported WFPs as wood products (HS4408-4421, HS940161, HS940169, HS940330, HS940340, HS940350, HS940360), paper products (HS48-49, HS4407), and wood pulp (HS4701-4706), excluding resource-based WFPs from the export category. This paper adopts a comprehensive approach to integrating the WFPs’ trade of China’s provinces with the global market, utilizing over 4 million trade data records from the Chinese Customs and United Nations Trade and Commerce databases.

This paper’s main data sources are shown as follows: (1) Export-related data from the United Nations trade database. (2) The interest income, interest expense, and beginning and ending values of interest-bearing capital for banking financial institutions of each province come from the Wind Information Terminal 2024. (3) Data on forestry industry output are sourced from the China Forestry and Grassland Statistics Yearbook. (4) Other data for Chinese provinces mainly come from the National Bureau of Statistics of China website. At the provincial level, 31 Chinese provinces are selected. At the importing country level, 184 countries are included, with the selection maximized except for some small countries with missing data. This study creates a three-dimensional panel dataset structured by year, province, and importing country, the period of which is set from 2007 to 2022.

In this study, bank sector profits (BSP) are proxied by the average EBIT-to-assets ratio of regional banks. However, the allocation of bank profits across provinces relies on assumptions regarding the distribution of bank branches, which may introduce potential biases if actual bank profits differ significantly from these assumptions. Given the lack of detailed provincial-level data on bank profits, we applied a simple allocation method based on branch distribution. However, this assumption may not fully reflect the true distribution of bank profits, especially in provinces with significant regional economic disparities. In future studies, we plan to refine this allocation method using more detailed, bank-level data that accounts for regional differences in profitability.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the variables in this study. The mean values for the

EMijt, IMijt, Qijt, and

Pijt are 0.239, 0.027, 0.022, and 3.405, respectively. The maximum and minimum values of each intensive and extensive margin differ widely, indicating the substantial differences in these WFPs’ export margins among different provinces. The mean value of BSP is 0.030, with a standard deviation of 0.008, which suggests that the difference in BSP among Chinese provinces is not too prominent.

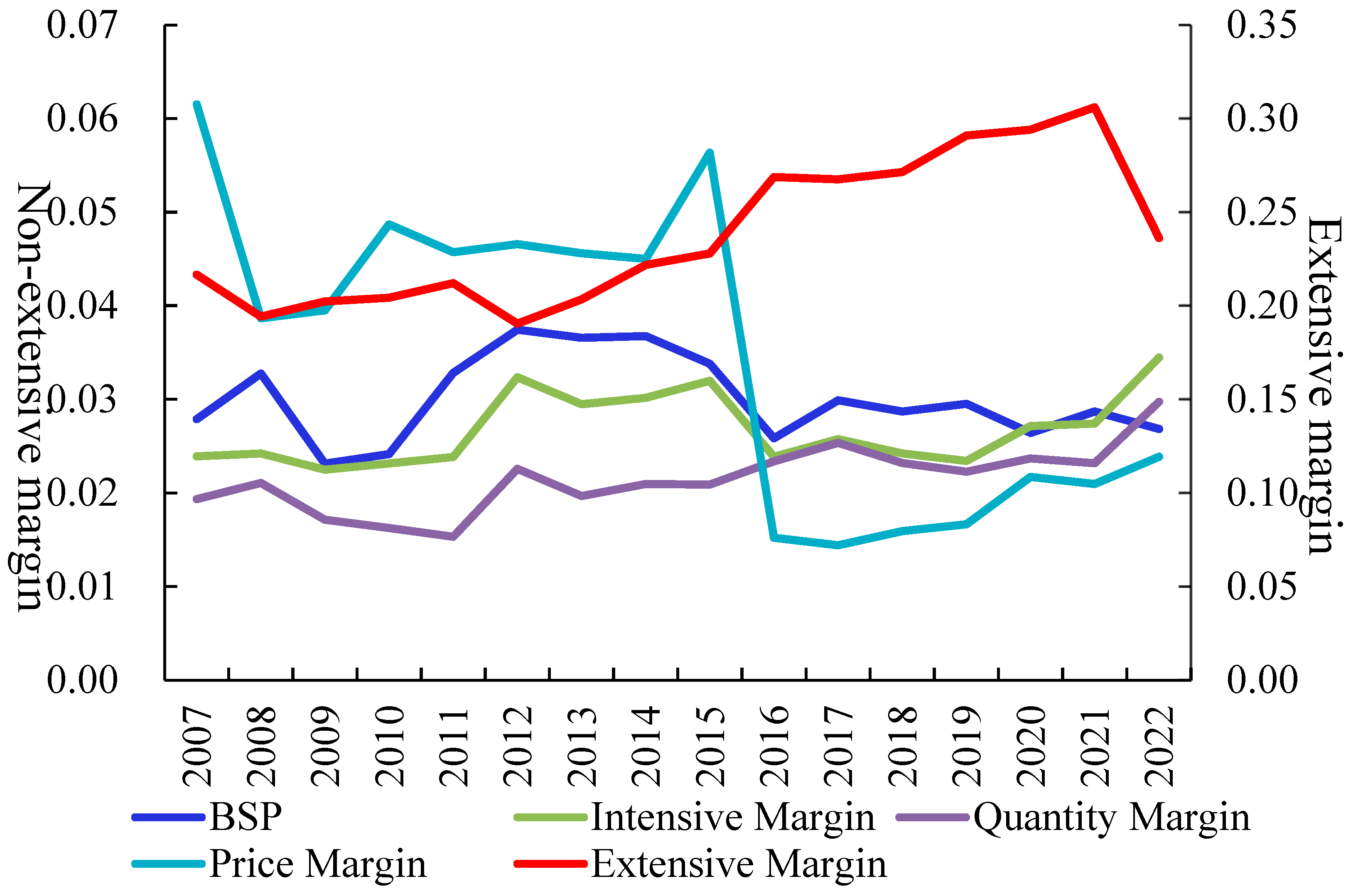

Figure 1 illustrates the annual average trends of regional BSPs and the export margins of WFPs across provinces. First, BSPs exhibit relatively frequent fluctuations: they increased rapidly from 2009 to 2012, declined sharply between 2012 and 2016, and have shown a generally declining trend with fluctuations since 2017. Second, the extensive margin of WFPs’ exports demonstrates an overall upward trend with fluctuations, except for a marked decline in 2022. The intensive margin of WFPs’ exports displays two relatively stable phases—at low and high levels—prior to 2016, followed by a fluctuating upward trend thereafter. From 2007 to 2022, the quantity margin also shows an overall increasing trend with fluctuations. The price margin experienced a sharp decline in 2016, after which it generally increased year by year. Third, a visual inspection of

Figure 1 suggests that the evolution of BSPs and the four export margins of WFPs often move in opposite directions across years, implying a potential negative correlation. However, this observation requires further confirmation through rigorous econometric analysis.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Baseline Regression Results

Table 2 reports the baseline regression results based on Equation (1). The estimated coefficients of BSPs for the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins are −0.584, −0.107, and −0.107, respectively, all statistically significant at the 1% level. These results indicate that regional BSPs significantly negatively affect the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins of WFPs’ exports. At the same time, they does not exert a statistically significant influence on the price margin. These findings strongly support Hypothesis 1 and align with the prior literature on the macroeconomic effects of financial sector profitability [

2,

6,

20,

44,

48]. The results also empirically validate several theoretical perspectives within the Chinese context, including Marx’s concept of profit sharing, the “financial over-development hypothesis”, the theory of financial predation, and the labor theory of value. These findings further challenge the classical theory of monetary neutrality. They suggest that profit-sharing between the banking sector and the real economy must consider the appropriate “quantity” of financial profits; excessive inflation of BSPs hinders the export development of the wood processing industry. Given the high-cost structure and persistently low profitability of wood product manufacturing enterprises in China, financial expenses substantially influence firm performance, making these firms particularly susceptible to the credit market’s “crowding-out effect”. Excessive regional BSPs may exacerbate the withdrawal of financial capital from the manufacturing sector, thereby impeding improvements in the extensive and intensive margins of WFPs’ export. Over time, this suppression of binary margins ultimately contributes to a contraction in the export volume of WFPs. These results contradict certain micro-level studies suggesting financing constraints may incentivize firms to enhance export margins [

69]. Our findings instead underscore the adverse effects of high BSPs on firms operating in cost-sensitive, low-margin industries, providing a more nuanced view of finance–trade dynamics in the context of developing economies.

In contrast, the coefficient for the price margin is not statistically significant. Theoretical frameworks from the trade literature suggest that in highly competitive markets, especially for homogeneous products like wood forest products, prices are often driven by global supply–demand dynamics rather than by the financing conditions of individual firms. Referring to the literature [

14], prices for standardized goods are set by market forces not by individual firm attributes, which may explain why BSP has limited influence on the price margin in such markets. Additionally, in the context of low-price competition, firms producing standard wood products may focus more on reducing production costs rather than adjusting their prices in response to changes in financing costs.

We believe that the research conclusions in this paper are more consistent with the actual development of the wood processing industry. Firms can alleviate internal and external financing constraints by shifting to “exports” or increasing exports [

70]. However, the high financial costs and the squeeze on low-profit industries caused by excessively high BSPs remains unsolved. The baseline regression results presented in

Table 2 address the primary research question by examining the relationship between BSPs and the export margins of WFPs. The negative and statistically significant coefficients for BSPs across the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins indicate that higher regional BSPs are associated with lower export margins. This result provides a direct answer to the research question and supports the hypothesis that BSPs negatively impact WFPs’ export margins.

5.2. Robustness Tests

This study conducts two robustness checks to validate the baseline regression results, whose results are reported in

Table 3. First, five provinces with substantial missing data and low export volumes—Gansu, Qinghai, Tibet, Ningxia, and Xinjiang—are excluded from the sample, and Equation (1) is re-estimated. The BSPs’ coefficients for the extensive, intensive, quantity, and price margins are −0.313, −0.191, −0.167, 0.005, respectively. The first three coefficients remain statistically significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient for the price margin is not significant. These findings are consistent with the baseline results, confirming the robustness of the negative relationship between BSPs and the key export margins of WFPs. Second, We use a

Poisson model to refit Equation (1). The results show that the BSP’s coefficients for intensive and quantity margins are −3.280 and −3.440, respectively, which are significant at the 1% level. The coefficient is negative for extensive margin but being positive for price margin, the direction is consistent with baseline regression.

5.3. Heterogeneity Test

Considering that the effects of BSPs may vary across different scenarios, heterogeneity tests are conducted based on two dimensions. China’s WFPs encompass various categories, generally divided into resource-intensive, labor-intensive, and capital- and technology-intensive WFPs. It is significant to explore whether the BSPs have differential effects on the export margins of WFPs with varying characteristics. We define plywood (HS4408-4413), wooden products (HS4414-4421), and wooden furniture (HS940161, HS940169, HS940330, HS940340, HS940350, HS940360) as labor-intensive WFPs, and pulp (HS4701-4706), paper, and paperboard (HS4707, HS48, HS49) as capital- and technology-intensive WFPs. Due to the minimal export volume of resource-intensive WFPs from China, they are excluded from this analysis. The results of distinguishing sample observations and refitting Equation (1) are shown in

Table 4. The BSPs’ impact coefficients on intensive margin, intensive margin, and quantity margin for labor-intensive WFPs are −0.120, −0.396, and −0.450, respectively. The impact coefficient on the extensive margin of capital-intensive products is −0.033. These results indicate that BSPs have a greater negative impact on the export margins of labor-intensive WFPs. The main reason is that labor-intensive enterprises are smaller in scale, have fewer tangible assets, are often located near raw material sources rather than consumer markets (urban areas), and are farther from banking financial institutions. At this point, the higher the local BSP level, the greater the probability that labor-intensive enterprises will face credit rationing and be “crowded out” by banking financial institutions. This ultimately makes it harder for enterprises to secure sufficient low-cost funding to open new export markets and deepen existing ones.

Second, the negative effects of BSPs on export margins disappeared following the implementation of China’s “financial concession” policy. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the Chinese government adopted this policy as a central measure to support the real economy. From 2020 to 2022, the State Council convened annual meetings to promote the policy for three consecutive years. In 2020 alone, the financial system extended CNY 1.5 trillion in benefits to the real economy through three main channels: interest rate reductions, direct monetary policy instruments, and fee reductions. Several of these measures remained in effect through the end of 2021 [

48].

In 2022, the People’s Bank of China issued the “Notice on Providing Financial Services for Epidemic Prevention and Control and Economic and Social Development”, reiterating the goal of “promoting financial institutions to reasonably benefit the real economy”. Additionally, in early 2023, in response to issues like high salaries and massive corruption in the financial sector, the Chinese government implemented the first large-scale “salary cap order” for the financial industry [

64]. Whether the financial concession policy can change the negative effects of BSPs is worth investigating. Based on the policy implementation years, this study divides the sample period into 2007–2019 (pre-implementation) and 2020–2022 (post-implementation). After dividing the sub-sample, Equation (1) is re-estimated. The results show that the direction of BSPs’ coefficient is consistent with the baseline model before the financial concession policy (see as

Table 5). However, after the policy is implemented, the negative effects of BSPs on extensive, intensity, and quantity margins disappear. These results provide micro-level evidence of the positive economic effects of the policy. This suggests that implementing and optimizing the financial concession policy is realistically feasible.

5.4. Moderating Effects Analysis

Based on the theoretical analysis in

Section 3.2, this study examines the moderating effects of three variables on the relationship between BSP and the export margins of WFPs: the number of bank institution outlets in a province (

Outlet), the proportion of rural bank institution outlets in a province (

Routlet), and the development of digital finance in a province (

DF).

First, an increase of the number of bank institution outlets in a province can mitigate the negative effects of BSPs. By manually retrieving data from the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission’s financial license website (

https://xkz.nfra.gov.cn/jr/, accessed on 12 February 2025), detailed data on the entry, loss of control, and exit of financial institutions in each province of China were compiled. The number of financial institution outlets in a province is calculated by adding the previous year’s and newly approved outlets and subtracting the outlets that lost control or exited. The result is then logged. We only retain bank institution outlets, excluding money brokerage firms, financial leasing companies, consumer finance companies, automotive finance companies, and other financial institutions (such as micro-loan companies, third-party wealth management companies, and integrated financial service companies). An interaction term between

BSP and

Outlet is included and re-estimated in Equation (1). The results show that the interaction term

BSP ×

Outlet has a coefficient of 0.258 for the intensive margin, which is significant at the 1% level. The coefficient for the extensive margin and quantity margin is positive, though insignificant. These results suggest that Hypothesis 2 is largely validated. An increase in the number of bank institution outlets can somewhat mitigate the negative effects of BSPs on regional WFPs’ export margins. This conclusion supports the view of financial supply geography and the theory of monetary non-neutrality. It rejects the “death of geography” assertion, which claims that the development of information technology can replace the importance of geographic factors in banking [

71]. The easier timber processing enterprises can access convenient financial products (services), the more they can advance international market development and expansion projects.

Second, an increase in the proportion of rural bank institution outlets in a province can alleviate the negative effects of BSPs. Bank institution outlets can be classified into three types based on their urban–rural distribution: primarily urban, primarily rural, and mixed urban–rural banking institutions. Rural banking institutions include rural credit cooperatives, rural commercial banks, village and township banks, rural cooperative banks, postal savings institutions (located in towns), and mutual aid societies (rural cooperatives). The Routlet is measured by the ratio of the number of rural bank institution outlets to the total number of bank institution outlets in a province. The interaction term between BSP and Routlet is set and re-estimated in Equation (1). The results show that the interaction term BSP × Routlet has coefficients of 3.853, 1.278, and 1.450 for the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins, respectively, all significant at the 1% level, validating Hypothesis 3. These results suggest that increasing the proportion of rural bank institution outlets in a province can reverse the negative effects of BSP on local WFPs’ export margins. This conclusion supports the view of the financial exclusion theory. Focusing on the increase in the number and proportion of bank institution outlets in rural areas, timber processing enterprises find it easier to access credit services from formal financial institutions. When the BSPs are high, the likelihood of facing financing difficulties and high financing costs decreases, leading to adequate financial support for export expansion.

Third, regional digital financial development can mitigate the negative effects of BSPs. This paper obtains

DF indicators from the Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index database, which is based on the consumption data provided by Ant Financial and uses AHP to calculate and compile the digital finance development index at the provincial level in China [

36]. The interaction term between BSPs and

Routlet is set and re-estimated in Equation (1). The results show that the interaction term

BSP ×

DF has coefficients of 0.002, 0.001, and 0.001 for the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins, respectively. All coefficients are significant at the 10% level, validating Hypothesis 4. The above results suggest that an increase in the level of digital financial development in a province can reverse the negative effects of BSPs on local WFPs’ export margins. This supports the cost-saving effect of digital financial development and the geographic expansion effect of financial services. In the capital markets where the banking sector pursues high profits and capital returns, the more mature the digital financial development in a region, the more likely timber processing enterprises with less collateral, located farther from cities and financial institutions, are to obtain credit to support export expansion. The moderating effect analysis explores how the relationship between BSPs and WFPs’ export margins is influenced by regional financial infrastructure, including the number of banking financial institution outlets, the proportion of rural banking outlets, and the development of digital finance. Each moderating variable is incorporated into the analysis through the inclusion of interaction terms with BSPs in the econometric model. The results, detailed in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, demonstrate that all three aspects of financial infrastructure can weaken the negative effects of BSPs on WFPs’ export margins. These findings address the research question concerning the moderating effects of financial infrastructure and provide specific insights into how different elements of financial infrastructure interact with BSP to influence export margins.

In summary, the empirical analysis of this study systematically verifies the four hypotheses and draws the following conclusions. First, higher regional BSPs significantly and negatively affect the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins of WFPs’ exports, supporting Hypothesis 1. This finding highlights the potential crowding-out effect of excessive banking sector profits on the real economy. Second, the negative impact of BSPs is more pronounced for labor-intensive WFPs, which face greater financing constraints due to their smaller scale and fewer tangible assets, thereby validating Hypothesis 2. Third, the implementation of China’s “financial concession” policy effectively mitigates the adverse effects of BSPs, demonstrating the practical significance of financial concession measures in promoting real economic development and confirming Hypothesis 3. Fourth, increasing the number of regional banking outlets, the proportion of rural banking outlets, and the level of digital finance development can all weaken the negative effects of BSPs on WFPs’ export margins, supporting Hypothesis 4. These findings collectively emphasize the importance of financial infrastructure and policy interventions in addressing the financing challenges faced by WFP enterprises and enhancing their export performance.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study set out to investigate BSPs’ impacts on the export margins of WFPs and to examine whether a “financial concession” policy can mitigate or amplify this effect. Drawing on a comprehensive dataset of WFPs’ export margins from 31 Chinese provinces to 184 countries over the period 2007–2022, we proposed and tested four hypotheses related to the negative effects of BSP on WFPs’ export margins and the moderating effects of regional financial infrastructure and policy interventions. The key findings are as follows: First, our results confirm that regional BSPs have significant negative effects on the extensive, intensive, and quantity margins of WFPs’ exports. This finding provides a direct answer to the research question regarding the impact of BSP on WFPs’ export performance and supports the hypothesis that higher banking sector profits can hinder the export expansion of WFPs. Second, the analysis reveals that labor-intensive WFPs are more vulnerable to the negative effects of BSPs, likely due to their smaller scale, fewer tangible assets, and greater distance from banking institutions. This addresses the question of whether the impact of BSPs varies across different types of WFPs and highlights the differential effects of financial factors on export margins. Third, this study demonstrates that China’s “financial concession” policy effectively mitigates the adverse effects of BSPs on WFPs’ export margins, offering empirical evidence for the policy’s practical significance and answering the question of how policy interventions can influence the relationship between BSPs and export performance. Fourth, the moderating effect analysis shows that a larger number of bank institution outlets, a higher share of rural bank institution outlets, and the development of digital finance can all weaken the negative effects of BSPs. This provides insights into the role of financial infrastructure in alleviating negative BSP impacts.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on prior research, this study advances policy recommendations for enhancing the export performance of WFPs and bolstering support for the real economy. Firstly, policymakers should continue to implement and refine the “reasonable financial preferential” policy. The government, central bank, and banking association must enhance the evaluation of policy implementation effects, accurately identify bottlenecks, and explore improvement plans. Leveraging the economic spillover effects of profit-sharing, a tiered financial franchise system should be established. This involves delineating responsibility allocation, precisely identifying beneficiaries, and devising appropriate policy instruments. The state-owned bank-dominated financial system ought to proactively reduce fees, implement financial incentives, address the excessive fees stemming from monopolistic practices, and utilize more flexible financial welfare instruments, such as interest rate cuts, fee reductions, and improved credit accessibility, to alleviate the financing constraints of WFPs, thereby increasing their export profit margins.

Secondly, to enhance the regional credit resource supply system, the coverage of banking institutions must be extended to rural and remote areas to improve credit access for enterprises within wood processing clusters. The digital transformation and financial innovation of banks should be steadily advanced. The use of information technologies like big data and cloud computing should be encouraged to facilitate the “precise drip irrigation” of fund supply and provide comprehensive and efficient services for the development of the real economy. The development of digital finance should be promoted to enhance the accessibility and efficiency of financial services for WFPs, thereby aiding their export business expansion.

Thirdly, local governments should enhance support policies for wood processing enterprises, particularly labor-intensive WFPs. Incentives such as site and rental subsidies should be provided to attract clusters of financial institutions and private investments. Financial support policies, such as loan interest subsidies and rent reductions, should be implemented to help these enterprises overcome financial disadvantages and boost their international competitiveness. These measures would foster a favorable financial environment for WFPs, improve their export profit margins, bolster the industry’s international competitiveness, promote sustained growth in WFOE export performance, and strongly support the stable and sustainable development of the real economy.