The Impact of Sustainable Tourism of Forest Ecosystems on the Satisfaction of Tourists and Residents—An Example of a Protected Area, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Theoretical Framework

2.2. Study Area

- In 2004, the reserve was included in the group of PARs important for the Danube basin (ICPDR);

- The reserve is a member of the Danube Network Protected Areas (DNPA) as one of the five PARs in Serbia;

- The reserve belongs to the group of IBA areas;

- It is a member of the European Emerald network;

- On 15 September 2021, the “Bačko Podunavlje” biosphere reserve was included in the “Mura-Drava-Danube” Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, which is the largest protected water reserve in Europe, designated by UNESCO (Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, and Serbia). The European Amazon is a common name for this large biosphere reserve that encompasses the Mura, Drava, and Danube rivers, with a length of 700 km. The PAR covers about 930,000 ha. This area includes 13 separate PARs in the mentioned countries of Europe [30,31,32,33].

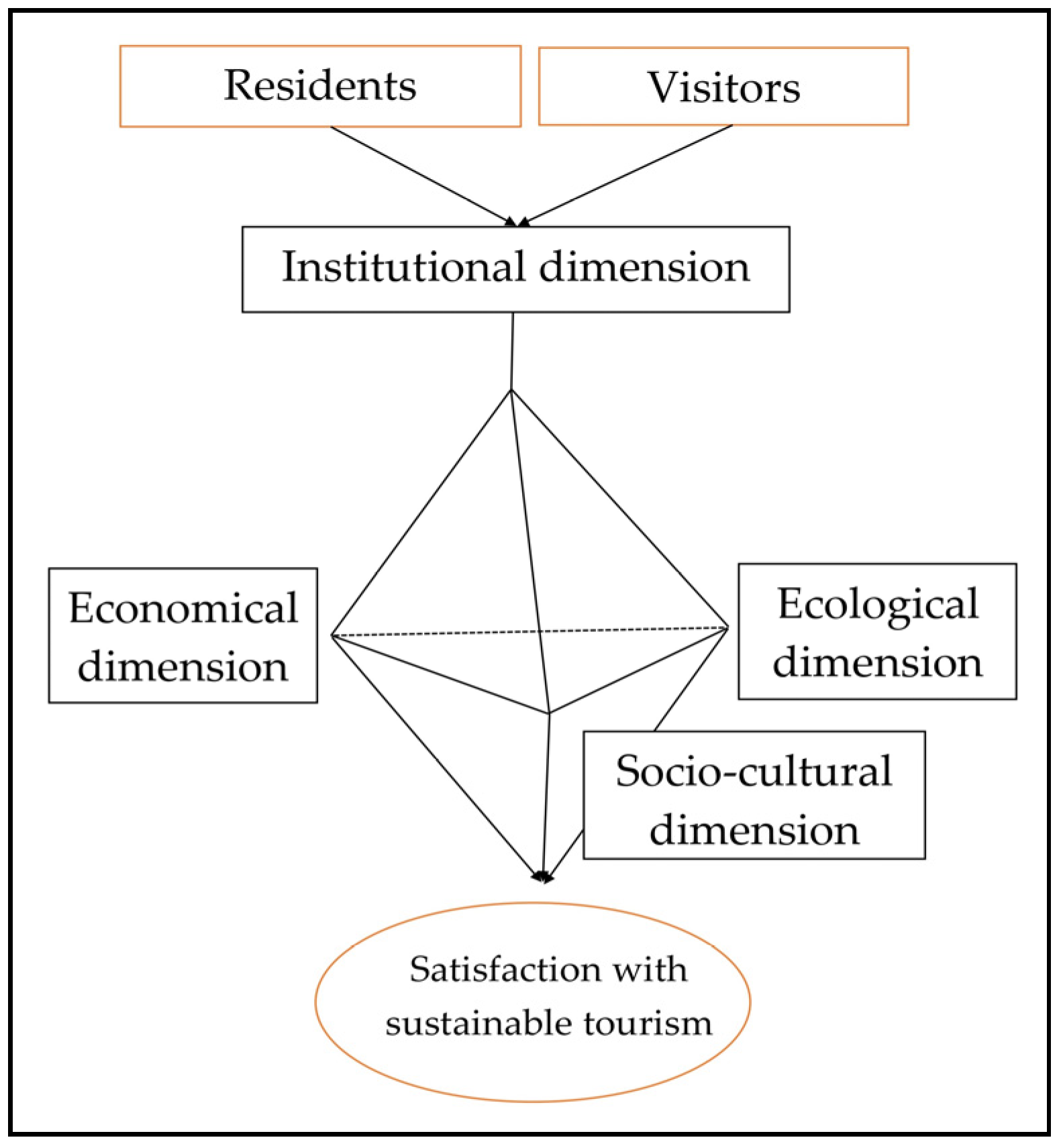

2.3. The Conceptual Model and Data Collection

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Providing the infrastructure required for easier access to the destination;

- Providing the locality’s spatial contents and equipment;

- Creating the conditions for an undisturbed stay in nature and the implementation of new types of tourism through the upgrading of the tourist range.

- The need of the local community for increased allocation of funds for equipping tourist sites;

- Greater financial support from the state for the planning and preservation of these areas;

- Further local participation through the business connections of all entities in the area;

- Empowerment of the management team.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Štetić, S.; Ristić, V.; Trišić, I.; Tomašević, V.; Skenderović, I.; Kurpejović, J. Nature Conservation and Tourism Sustainability: Tikvara Nature Park, a Part of the Bačko Podunavlje Biosphere Reserve Case Study. Forests 2025, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, T. Recreational potential as an indicator of accessibility control in protected mountain forest areas. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Peng, P.; Fan, S.; Liang, J.; Ye, J.; Ma, Y. Formation Mechanism of Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior in Wuyishan National Park, China, Based on Ecological Values. Forests 2024, 15, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Huang, S.S.; Dowling, R.K.; Smith, A.J. Effects of social and personal norms, and connectedness to nature, on pro-environmental behavior: A study of Western Australian protected area visitors. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 42, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonye, S.Z.; Yiridomoh, G.Y.; Nsiah, V. Multi-stakeholder actors in resource management in Ghana: Dynamics of community-state collaboration in resource use management of the Mole National Park, Larabanga. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.; Lee, J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, P.; Butchart, S.H.; Brooks, T.M.; Langhammer, P.F.; Marnewick, D.; Vergara, S.; Yanosky, A.; Watson, J.E. Protected area targets post-2020. Science 2019, 364, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičić, D. Turizam i Životna Sredina: Koncepcija Održivog Turizma (Tourism and the Environment: The Concept of Sustainable Tourism); Zadužbina Andrejević: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism Programme Planning; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Yoon, Y.S.; Hall, C.M. Tourism green growth through technological innovation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Abooali, G.; Henderson, J. Community capacity building for tourism in a heritage village: The case of Hawraman Takht in Iran. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G. Community participation in tourism planning at majete wildlife reserve, Malawi. Quaest. Geogr. 2021, 40, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.; Kondolf, G.M. How Eco is Eco-Tourism? A systematic assessment of resorts on the Red Sea, Egypt. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ao, C.; Liu, B.; Cai, Z. Ecotourism and sustainable development: A scientometric review of global research trends. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukolić, D.; Gajić, T.; Petrović, M.D.; Bugarčić, J.; Spasojević, A.; Veljović, S.; Vuksanović, N.; Bugarčić, M.; Zrnić, M.; Knežević, S.; et al. Development of the Concept of Sustainable Agro-Tourism Destinations—Exploring the Motivations of Serbian Gastro-Tourists. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.; Lawton, L. Tourism Management; John Wiley & Sons: Milton, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas, Guidelines for Planning and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Hughes, K.; Ding, P.; Liu, D. Chinese and international visitor perceptions of interpretation at Beijing built heritage sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Ecotourism behavior of nature-based tourists: An integrative framework. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Thapa, B.; Kim, H. International Tourists’ Perceived Sustainability of Jeju Island, South Korea. Sustainability 2017, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of personal benefits from, and support of, tourism development: The role of relational quality and quality-of-life. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzović, S.; Radovanović-Jovin, H. (Eds.) Životna Sredina u Autonomnoj Pokrajini Vojvodini: Stanje-Izazovi-Perspektive (Environment in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina: Status-Challenges-Perspectives); Pokrajinski Sekretarijat za Urbanizam, Graditeljstvo i Zaštitu Životne Sredine: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2011. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Lazić, L.; Pavić, D.; Stojanović, V.; Tomić, P.; Romelić, J.; Pivac, T.; Košić, K.; Besermenji, S.; Kicošev, S. Protected Natural Resources and Ecotourism in Vojvodina; Prirodno-Matematički Fakultet, Departman za Geografiju, Turizam i Hotelijerstvo, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2008. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, V.; Mijatov, M.; Dunjić, J.; Lazić, L.; Dragin, A.; Milić, D.; Obradović, S. Ecotourism impact assessment on environment in protected areas of Serbia: A case study of Gornje Podunavlje Special Nature Reserve. Geogr. Pannonica 2021, 25, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Privitera, D.; Štetić, S.; Petrović, M.; Radovanović, M.; Maksin, M.; Šimičević, D.; Stanić Jovanović, S.; Lukić, D. Sustainable tourism to the part of Transboundary UNESCO Biosphere Reserve “Mura-Drava-Danube”. A case of Serbia, Croatia and Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M. Heading forward to the “Mura–Drava–Danube Transboundary Biosphere Reserve”. Zbornik Matice Srpske za Društvene Nauk. 2014, 147, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csagoly, P.; Magnin, G.; Mohl, A. Danube, Drava, and Mura Rivers: The “Amazon of Europe”. In The Wetland Book; Finlayson, C.M., Milton, G.R., Prentice, R.C., Davidson, N.C., Eds.; Springer: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, V.; Mijatov Ladičorbić, M.; Dragin, A.S.; Cimbaljević, M.; Obradović, S.; Dolinaj, D.; Jovanović, T.; Ivkov-Džigurski, A.; Dunjić, J.; Nedeljković Knežević, M.; et al. Tourists’ motivation in wetland destinations: Gornje Podunavlje Special Nature Reserve case study (Mura-Drava-Danube Transboundary Biosphere Reserve). Sustainability 2023, 15, 9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidžić, L.; Krasulja, S.; Belij, S. (Eds.) Protected Natural Resources in Serbia; Ministry of Environmental Protection, Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Environmental space and the prism of sustainability: Frameworks for indicators measuring sustainable development. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Cutumisu, N. Sustainable tourism development strategy in WWF Pan Parks: Case of a Swedish and Romanian national park. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Shen, F.; Ritter, P. Resident perceptions of sustainable tourism in Chongdugou, China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Cottrell, S.P. A sustainable tourism framework for monitoring residents’ satisfaction with agritourism in Chongdugou Village, China. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2008, 1, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Vaske, J.J.; Roemer, J.M. Resident satisfaction with sustainable tourism: The case of Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 8, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. The structural relationship between tourist satisfaction and sustainable heritage tourism development in Tigrai, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2019, 5, E01335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.U.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, S. Residents’ satisfaction with sustainable tourism: The moderating role of environmental a wareness. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2022, 3, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Shapovalova, A.; Lan, W.; Knight, D.W. Resident support in China’s new national parks: An extension of the Prism of Sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 1731–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Environmental Space-Based Proactive Linkage Indicators: A Compass on the Road Towards Sustainability. In Sustainability Indicators, Report of the Project on Indicators of Sustainable Development; Moldan, B., Billharz, S., Eds.; Wiley: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Raadik, J. Socio-cultural benefits of PAN Parks at Bieszscady National Park, Poland. Matkailututkimus 2008, 1, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huayhuaca, C.; Cottrell, S.; Raadik, J.; Gradl, S. Resident perceptions of sustainable tourism development: Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2010, 3, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, J.; Dubois, G. Tourism and sustainable development indicators: The gap between theoretical demands and practical achievement. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, P.J.; Ormsby, A.A. A comparative study of local perceptions of ecotourism and conservation at Five Blues Lake National Park, Belize. J. Ecotourism 2011, 10, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samora-Arvela, A.; Ferreira, J.; Vaz, E.; Panagopoulos, T. Modeling nature-based and cultural recreation preferences in Mediterranean regions as opportunities for smart tourism and diversification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.B.; Shams, R. Economy and ecology: Encounters and interweaving. Sustainability 2020, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Štetić, S.; Candrea, A.N.; Nechita, F.; Apetrei, M.; Pavlović, M.; Stojanović, T.; Perić, M. The impact of sustainable tourism on resident and visitor satisfaction—The case of the Special Nature Reserve “Titelski Breg”, Vojvodina. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G.; Carr, N.; Lovelock, B. Community participation framework for protected area-based tourism planning. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 13, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, T.; Trišić, I.; Brđanin, E.; Štetić, S.; Nechita, F.; Candrea, A.N. Natural and sociocultural values of a tourism destination in the function of sustainable tourism development—An example of a protected area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sowinska-Świerkosz, B.; Chmielewski, T.J. Comparative assessment of public opinion on the landscape quality of two biosphere reserves in Europe. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Sanabria, R.; Skinner, E. Sustainable tourism and ecotourism certification: Raising standards and benefits. J. Ecotour. 2003, 2, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya, E.; Teye, V.; Sonmez, S. Understanding residents’ support for tourism development in the Central region of Ghana. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, L.; Hausner, V.; Brown, G.; Runge, C.; Fauchald, P. Identifying spatial overlap in the values of locals, domestic and international tourists to protected areas. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S. Transforming travel: Realising the potential of sustainable tourism. J. Ecotour. 2019, 18, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The evolution of sustainable development and sustainable tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C.M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, W.; Hall, C.M. Reinterpreting the creation myth: Yellowstone National Park. In Tourism and National Parks, International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change, 1st ed.; Frost, W., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, , 2009; pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- McCool, S.F.; Moisey, R.N.; Nickerson, N.P. What should tourism sustain? The disconnect with industry perceptions of useful indicators. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schianetz, K.; Kavanagh, L. Sustainability indicators for tourism destinations: A complex adaptive systems approach using systemic indicator systems. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A. Environment and Tourism, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C.A.; Polley, A. Defining indicators and standards for tourism impacts in protected areas: Cape Range National Park, Australia. Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying core indicators of sustainable tourism: A path forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.M. Sustainable ecotourism in Amazonia: Evaluation of six sites in Southeastern Peru. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J.C.; Humphreys, C. The Business of Tourism; Pearson education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Butzmann, E.; Job, H. Developing a typology of sustainable protected area tourism products. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1736–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Viljoen, A.; Saayman, M. Who visits the Kruger National Park and why? Identifying target markets. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; Romagosab, F.; Buteau-Duitschaeverc, W.C.; Havitza, M.; Glovera, T.D.; McCutcheona, B. Good governance in protected areas: An evaluation of stakeholders’ perceptions in British Columbia and Ontario Provincial Parks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A. Nature-based tourism and environmental sustainability in South Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 136–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.A.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism, Ecology, Impacts, and Management; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K. Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgadoa, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges de Lima, I.; Green, R.J. Wildlife Tourism, Environmental Learning and Ethical Encounters, Ecological and Conservation Aspects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nechita, F.; Lozo, I.; Candrea, A.N. National parks’ web-based communication with visitors. Evidence from Piatra Craiului National Park in Romania and Paklenica National Park in Croatia. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. 2014, 7, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.M.; Hall, C.M. Geographies of tourism development and planning. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, M.; Kruger, M.; Saayman, M. Determinants of visitor length of stay at three coastal national parks in South Africa. J. Ecotour. 2015, 14, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, S.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Jasrotia, A. Sustainable tourism and residents’ satisfaction: An empirical analysis of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Delhi (India). J. Hosp. Appl. Res. 2023, 18, 70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, K.; Ali, F.; Ragavan, N.A.; Manhas, P.S. Sustainable tourism and resulting resident satisfaction at Jammu and Kashmir, India. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2015, 7, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, I. The Development of a conceptual model to support sustainable tourism policy in north mediterranean destinations. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 710–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banos-Gonzales, I.; Martinez-Fernandez, J.; Esteve-Selma, M.A. Using dynamic sustainability indicators to assess environmental policy measures in Biosphere Reserves. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Miller, G. Transforming societies and transforming tourism: Sustainable tourism in times of change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The attitude of tourist destination residents towards the effects of overtourism—Kraków case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: A longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Ecological indicators of tourist impacts in parks. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschinis, C.; Swait, J.; Vij, A.; Thiene, M. Determinants of recreational activities choice in protected areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktymbayeva, A.; Nuruly, Y.; Artemyev, A.; Kaliyeva, A.; Sapiyeva, A.; Assipova, Z. Balancing nature and visitors for sustainable development: Assessing the tourism carrying capacities of Katon-Karagay National Park, Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.L.; Cabrera, A.T.; Gomez del Pulgar, M.L. The potential role of cultural ecosystem services in heritage research through a set of indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Exploring resident–tourist interaction and its impact on tourists’ destination image. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambura, G.; Maceci, N.; Jani, D. Residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism and satisfaction: Evidence from Zanzibar. J. Geogr. Assoc. Tanzan. 2022, 42, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D. Ecotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Štetić, S. Geografija Turizma (Geography of Tourism); LI: Belgarde, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Participants | Goals and Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Tourists | To make high-quality nature experiences available. |

| Tourism industry (including private and public sectors), tourism trade, and associations | Tourism growth; Maximizing profits for travel agencies and tour operators. |

| State services and organizations dealing with the promotion of forest tourism | Economic, social, and ecological growth of sustainable forest tourism; High-quality operators and experience. |

| Local community | Increasing profits for local communities; Reducing the tourism impacts; Reducing the forest resource use. |

| Environmental managers, especially government environmental agencies | Ecological sustainability of tourist activities; Satisfaction of recreation goals; Using tourism to support conservation goals. |

| Non-governmental organizations dealing with the protection and preservation of the endangered flora and fauna of the forests | Minimizing threats by protecting and/or providing benefits to forest nature; Using tourism to support conservation goals. |

| Forests, nature, and environment | In general, the interests of nature are assumed to be reflected in the goals of the latter two groups of participants. |

| Items | Residents (n = 705) | Visitors (n = 535) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of sustainable tourism | (α) | Mean | (α) | Mean |

| Institutional dimension | 0.789 | 3.45 | 0.811 | 3.53 |

| Residents work as trained guides in the forest-protected area | 2.14 | 2.78 | ||

| There are local brands | 4.11 | 4.14 | ||

| Instructions on forest protection are followed | 4.01 | 3.96 | ||

| Information is available about the protection of the forest reserve, the history, and the culture of the population | 3.54 | 3.21 | ||

| Ecological dimension | 0.809 | 3.63 | 0.781 | 3.70 |

| There are activities of nature protection | 3.09 | 3.11 | ||

| There are tourist facilities and services in the reserve | 4.12 | 4.21 | ||

| There are facilities for tourists that do not have a negative impact on the environment | 3.68 | 3.77 | ||

| Economic dimension | 0.804 | 3.08 | 0.859 | 3.46 |

| There are benefits to tourism for the locals | 3.22 | 3.15 | ||

| Tourism impacts the local economy | 2.84 | 3.03 | ||

| Tourism contributes to the employment of residents | 2.17 | 3.02 | ||

| Local products are part of the tourism offer | 4.03 | 4.02 | ||

| Prices of domestic products and tickets are acceptable | 3.12 | 4.09 | ||

| Sociocultural dimension | 0.811 | 3.77 | 0.869 | 3.87 |

| Visitors are interested in domestic crafts and products | 4.14 | 4.21 | ||

| Visitors make contact with residents | 4.09 | 3.89 | ||

| Visitors are interested in local traditions and customs | 4.15 | 4.33 | ||

| Visitors visit local cultural facilities and events | 3.25 | 3.28 | ||

| Tourists visit historical sites | 3.20 | 3.64 | ||

| Index | Residents (n = 705) | Visitors (n = 535) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (α) | Mean | (α) | Mean | |

| 0.814 | 3.65 | 0.821 | 3.39 | |

| Tourism creates benefits for the forest (nature) | 4.11 | 3.96 | ||

| Tourism creates benefits for residents and visitors | 3.52 | 3.28 | ||

| There are possibilities for the development of tourism | 3.87 | 4.03 | ||

| I am satisfied with the tourist attractions | 3.11 | 2.29 | ||

| Satisfaction | Residents | Visitors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1 | p-Value | β1 | p-Value | |

| Institutional | 0.109 | 0.054 | 0.211 | 0.021 |

| Ecological | 0.203 | 0.041 | 0.203 | 0.111 |

| Economic | 0.105 | 0.021 | 0.101 | 0.001 |

| Sociocultural | 0.211 | 0.009 | 0.202 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vukadinović, L.; Trišić, I.; Ristić, V.; Candrea, A.N.; Štetić, S.; Apetrei, M. The Impact of Sustainable Tourism of Forest Ecosystems on the Satisfaction of Tourists and Residents—An Example of a Protected Area, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Forests 2025, 16, 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060909

Vukadinović L, Trišić I, Ristić V, Candrea AN, Štetić S, Apetrei M. The Impact of Sustainable Tourism of Forest Ecosystems on the Satisfaction of Tourists and Residents—An Example of a Protected Area, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Forests. 2025; 16(6):909. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060909

Chicago/Turabian StyleVukadinović, Lazar, Igor Trišić, Vladica Ristić, Adina Nicoleta Candrea, Snežana Štetić, and Manuela Apetrei. 2025. "The Impact of Sustainable Tourism of Forest Ecosystems on the Satisfaction of Tourists and Residents—An Example of a Protected Area, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia)" Forests 16, no. 6: 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060909

APA StyleVukadinović, L., Trišić, I., Ristić, V., Candrea, A. N., Štetić, S., & Apetrei, M. (2025). The Impact of Sustainable Tourism of Forest Ecosystems on the Satisfaction of Tourists and Residents—An Example of a Protected Area, Vojvodina Province (Northern Serbia). Forests, 16(6), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060909