1. Introduction

Anthropogenic pressure is a major driver of ecosystem degradation, affecting its structure and functioning by modifying biological and physicochemical processes [

1,

2,

3]. Highly dependent on natural resources, in response to continued development and population growth, humanity is increasingly putting pressure on the biosphere and exploiting various ecosystem services [

4]. For centuries, humans have transformed natural landscapes into various land use activities, ranging from farmland production and forestry to urbanisation, to surpass their essential needs [

4]. Such a situation led to the intensification of land use and land cover changes (LULCC), the over-explorative and intensive conversion of one cover type to another and its consequent exploitation by human activities to acquire natural resources and fulfil human needs [

5,

6,

7].

Despite land use activities being essential for humanity, their harmful effects on ecosystems are well known, primarily causing ecosystem degradation and biodiversity decline. Since the 19th century, LULCC have been responsible for approximately 35% of CO

2 emissions into the atmosphere [

8], with impacts on climate from local to global scale [

4,

9,

10]. The transformation of natural ecosystems into agriculture or urban areas through deforestation is among the reasons for carbon cycle modification and emissions [

5,

8]. Another negative effect of LULCC includes, for example, the deterioration of water courses caused by urbanisation or nutrient and agrochemical pollution by agriculture intensification, infectious diseases propagation and soil degradation [

4,

11].

Riparian zones are transitional areas between the terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems of great ecological importance, balancing temperature and providing organic matter and nutrients for the great diversity they harbour [

12,

13]. They can act as buffer zones from the effect of habitat fragmentation and mitigate the harmful impacts of exotic woody species from the surroundings [

14,

15,

16]. Similarly, riparian forests are considered highly diverse, dynamic and complex biophysical habitats that function as interfaces between terrestrial and aquatic systems, encompassing sharp environmental gradients, ecological processes and communities [

17]. Because of this, they may contribute significantly to landscape connectivity, facilitating dispersal and migration of forest-dependent bird species [

18], acting as corridors. The structural complexity of riparian forests, including diverse vegetation layers and proximity to water, enhances habitat quality, making these areas key biodiversity hotspots [

19,

20]. However, riparian habitats are vulnerable to perturbation and are progressively threatened not only by water pollution but also by land use changes and occupation by invasive alien species [

21,

22,

23].

Recent studies highlight the essential role of riparian corridors in supporting biodiversity and avian communities across the globe, from tropical [

24] to temperate ecosystems, such as those found in Europe [

25,

26]. Riparian corridors provide critical resources, such as nesting sites, food and stopover habitats during migration, supporting diverse bird assemblages [

27]. In southern Europe, riparian forest systems act as vital refuges for forest-breeding birds, especially in fragmented agricultural areas, where they sustain higher species richness and abundance compared to surrounding habitats, favouring, for instance, species of conservation concern [

28,

29,

30]. Since birds are usually more responsive to disturbances to their habitats than other cohabitating organisms [

31], conservation and restoration of riparian habitats are thus critical strategies for maintaining avian diversity and ensuring the ecological integrity of European landscapes [

32,

33,

34]. Also, their ecology and connection with the vegetation and landscapes are, in general, well known [

35,

36]; they are often more conspicuous and easier to survey and study than other taxa [

37], thus being commonly used as bioindicators of disturbance in riparian corridors.

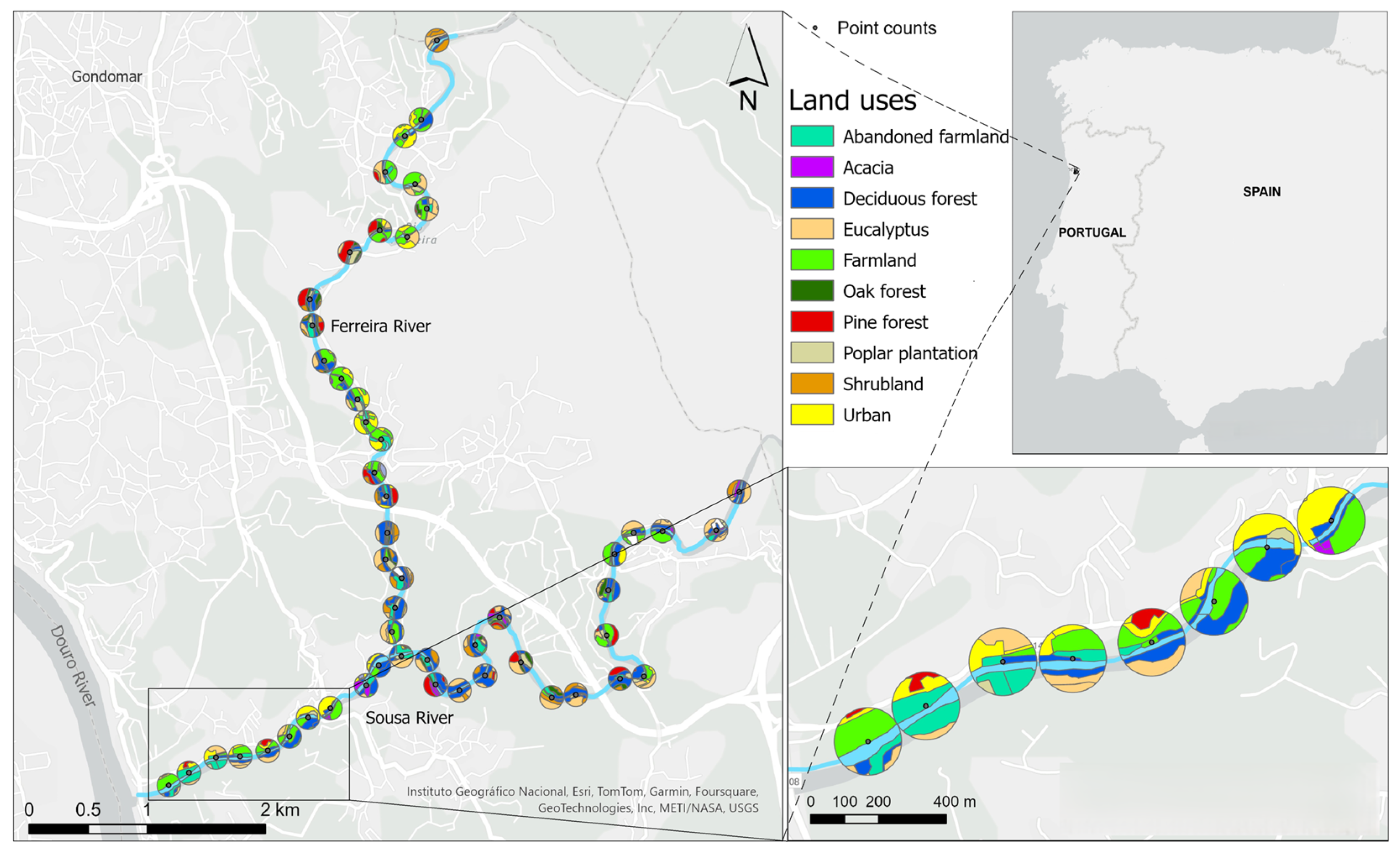

The objectives of the study are (i) to characterise the bird community in the riparian corridors along two very disturbed rivers in a largely urbanised area of northern Portugal throughout the year (wintering season, breeding season and post-breeding migration period); (ii) to understand the importance of riparian corridors as breeding, wintering and migratory stopover habitats for different bird assemblages; (iii) to determine the effects of land use on the composition and abundance of riparian bird community; (iv) to evaluate the usage of bird assemblages as indicators of riparian ecosystem health. Spatial and temporal variations in bird community were examined, and we also analysed the abundance of specific assemblages reflecting trophic, habitat preference, phenology and foraging substratum affinities to understand how they were affected by different land uses. We hypothesise that riparian corridors have a particular importance for migratory birds, that birds that feed on plant material are related to anthropogenic and perturbed landscapes and that invertivore (insectivores sensu lato, i.e., those that feed on invertebrates) abundance serves as a good ecological state indicator of riparian areas [

38,

39]; thus, it will likely increase in areas composed mostly of natural habitats (e.g., native deciduous riparian forests), whereas areas dominated predominantly by exotic plant species will negatively impact bird communities.

4. Discussion

This study underpins the seasonal importance of riparian forest corridors for avian communities. Results suggest that Iberian riverine habitats may play an important role as stopover sites for the autumnal Afro-Western Palearctic migrant flyway, with several long-distance migrants using this region’s riparian forest ecosystems. They are also considerably important for short-distance migrant species, which use the area as a wintering ground. Additionally, this study highlights the importance of different land uses for avian community composition, as the bird assemblages’ abundance varied greatly across the riparian landscape, suggesting an overall detrimental impact of invasive alien tree species on the avian community. Pine, oak and poplar tree planted forests had several positive associations with a range of bird assemblage abundances in different seasons, namely forest birds, omnivores, tree and understorey foragers and invertivores. Contrary to our expectations, we noticed that the deciduous riparian forest when associated with shrubland had no significantly positive relation with any bird assemblage. This study also consolidates the view that certain avian assemblage groups such as invertivores, granivores, ground foragers and both forest and farmland birds, can be used as bioindicators of deterioration in riparian landscapes. This was evidenced in our study by the negative associations of these bird assemblages with anthropogenic land uses and positive associations with natural land covers.

The bird community in our study area was typical of riverine habitats in the Atlantic region [

59] such as the common kingfisher (

Alcedo atthis) or the grey wagtail (

Motacilla cinerea), with the presence of species associated with other habitats, such as shrublands (e.g., the Dartford warbler (

Curruca undata) and the rock bunting (

Emberiza cia)) due to natural or human-induced habitat heterogeneity of land uses adjacent to the water course. However, species typical of this geographic region but scarcer and with stricter habitat requirements, such as the white-throated dipper (

Cinclus cinclus) [

59], were absent. The presence/absence of such species can serve as a bioindicator of water and habitat quality, since they occupy high trophic levels on aquatic food webs and are often highly sensitive to environmental changes [

60,

61,

62].

The bird community of the Ferreira and Sousa Rivers is predominantly dominated by resident species, while migrants constitute 27% of the overall community. Species richness was higher in the wintering and post-breeding migration seasons than in the breeding season, possibly suggesting a relatively impoverished breeding community, which may be linked with habitat disturbance. In fact, there are some studies associating the decrease in the number of species in the riparian corridors with the deterioration (or even absence) of riparian vegetation across the water lines [

63], particularly in breeding passerine populations [

64]. We found significant seasonal differences in the number of species for all bird assemblages, with the exception of granivores, forest birds, residents, ground foragers and understorey foragers, and in abundance, with the exception of invertivores, tree foragers and farmland birds. As nesting sites, both rivers host lower numbers of species compared to the other two seasons. The breeding community mostly comprised residents and common species, with a scarcity or even absence of breeding migrants, such as the common cuckoo (

Cuculus canorus) or the Iberian chiffchaff (

Phylloscopus ibericus). This is in line with other studies in other European riparian galleries [

25,

38,

65]. Forest birds (e.g., the firecrest, the great tit, the long-tailed tit and the song thrush) and understorey specialist bird species (e.g., the blackcap and the wren) dominated the breeding community. The verified seasonal pattern of the community reflects the dynamics of different bird assemblages and how they respond to the particularities of each season. Some of the species included as residents actually have short- and long-distance migratory individuals in their wintering and post-breeding migratory populations. In the winter, the European robin, the common chaffinch and the song thrush reached their peak abundance as a result of the migration of individuals from higher latitudes [

66], while exclusively wintering species, such as the chiffchaff and the siskin, were also frequent and abundant. This high influx of wintering birds occurs because such species find mild weather conditions and greater availability of resources to survive the winter in the Iberian Peninsula [

67,

68]. The humid and milder conditions of winter in this region under the influence of the Atlantic climate boost ecosystem productivity and as a result increase the availability of invertivores and seeds, which are crucial food resources for invertivore, granivore and omnivore species [

67,

68,

69]. Also, during the migratory passage, both species from northern Europe and species returning to their African wintering grounds cohabit the riparian corridors of both rivers. Moreover, the occurrence of more specific habitat species, such as the purple heron (

Ardea purpurea) or the common reed warbler (

Acrocephalus scirpaceus), typically associated with wetlands and dense reedbeds, respectively [

70], exemplifies the importance of riparian corridors as migratory stopover sites for birds that must fulfil the energy demands of migration [

71].

Our results are in line with other studies suggesting that invertivores and tree foragers are associated with undisturbed riparian areas, and birds feeding on plant material point to altered riparian habitats [

38,

39]. The obtained associations between bird assemblages and different land use gradients that can be equated with habitat disturbance, corroborate that particular bird assemblages can be considered as bioindicators of riparian integrity, and reflect the extent to which different land uses affect riparian bird communities. This was showed by the positive relation of the abundance of farmland, ground-foraging and granivore species with anthropogenic land uses (farmlands, urban areas, acacia stands) and the negative relation with more natural habitats (deciduous riparian forests, shrublands, pinewood and oakwood). Conversely, the abundance of invertivores and tree foragers were positively related with natural land uses and negatively related with altered uses, such as farmlands, urban areas or acacia stands.

The gradient of deciduous forest connected to shrubland over farmland, which represents open habitats and anthropogenic disturbance of riparian galleries, negatively and significantly affected bird assemblages all year round, with the exception of ground foragers during the wintering season. We noticed an absence of positive effects of this gradient on invertivores, known to be a good indicator of riparian integrity [

38]. We believe that an absence of a positive relation with this group can be justified by invertivores in riparian corridors being affected by the presence of crops in the surrounding areas, since farmlands were frequently connected to riparian galleries in our study area. This is supported by Martin et al. (2006) [

72], who stated that this habitat is sensitive to modification of adjacent landscapes. Also, in their study in a Mediterranean riparian gallery, Pereira et al. (2014) [

25] conclude that the surroundings have an influence on bird assemblages during the breeding season. On the other hand, our study not only suggests that these effects occur in breeding populations but that they also affect wintering and migratory populations. The lack of any significantly positive relations can indicate that the vertical connectivity between riparian deciduous forests and shrublands of

Erica spp.,

Ulex spp. and

Cytisus striatus does not benefit the forest-related and invertivores bird assemblages.

The abundance of forest birds and omnivores was favoured by the woody associations of pine, oak and poplar tree stands during migration. During winter, this gradient was particularly important for the increase in abundance of invertivores and tree-foraging birds. In the breeding season, the gradient continued to influence the abundance of invertivores and was also important for ground foragers. The positive relation with understorey birds during the breeding season indicates that this forest association, which integrates some production stands of (mainly) exotic poplar trees, still contains a well-developed understorey layer. Usually, forest production management removes the understorey and shrublands of these stands [

73]. When properly managed and without applying intensive control on the associated vegetation, native stands for production can provide good conditions for the establishment of native bird species [

74].

Our results reflected the harmful effects of forest stands dominated by invasive species on bird communities in riparian corridors. The eucalyptus stands over urban area gradient was negatively related with the abundance of granivores during all seasons, ground foragers during the breeding season, unspecialised foragers and non-breeding birds in winter, forest birds in winter and farmland birds in the breeding season. The eucalyptus spreads and overtakes native forests due to its high growth capacity [

75,

76]. Additionally, these species bloom during winter, which can cause the displacement of food availability and ideal habitat conditions for birds when replacing native species [

77]. A similar relation occurs with stands of

Acacia spp. The increase in these invasive species was the gradient of highest importance in explaining the negative effects on the abundance of forest birds during the migration period and the breeding season. It also negatively impacted generalists and other habitat specialists and ground foragers in the breeding season. Although the abundance of two bird assemblages—farmland birds and ground foragers—was positively related with this gradient in the migration season, since the acacia stands were generally on the edge of farmland, we believe this association is a result of edge effects [

78]. We also considered the positive effects on the abundance of farmland birds and ground foragers as an indicator of anthropogenic disturbance.

The process of ecological succession transforms these former croplands into low-shrubland areas [

79], with tall herbaceous plant associations and sparse younger stages of pioneer woody species. The abandonment of farmlands present in riparian corridors increases the abundance of invertivores and tree foragers in winter and in the breeding season, respectively, and it negatively affects carnivores in the migration period and the abundance of granivores, ground foragers and farmland birds in the breeding season. Soil moisture and the typical mild winter climate of the region likely contribute to the abundance of invertebrates, an important trophic resource for invertivore and omnivore species [

68]. In these habitats, we observed high densities of small arthropods, mostly arachnids, in the vegetation during the fall and winter campaigns (personal observations). Some species like Cetti’s warbler and the dunnock (

Prunella modularis) were frequently detected in these areas.

5. Conclusions

This study adds to our understanding of the dynamics of riparian bird communities in northwestern Iberian Peninsula and supports the use of functional bird assemblages to assess the effects of disturbed landscapes. It also corroborates other studies on riparian corridors, suggesting that these sensitive habitats are fundamental to maintaining a diversified and rich avian community in human-dominated landscapes [

80]. This study contributes to filling the gap in our knowledge of the Atlantic riparian bird communities in Portugal, as the only studies we are aware of have been conducted in Mediterranean riparian corridors [

25,

29]. Additionally, we provide information on the effect of invasive woody species, namely eucalyptus and acacias, and the possible effects of these land uses. To our knowledge, only one study has addressed the impact of invasive wattle acacia stands on local bird communities in the Iberian Peninsula [

81], making our findings relevant and a starting point to future research.

For further studies, we suggest the application of environmental data that reflect the structural and ecological features of riparian corridors, such as riparian width, the percentage of invasive plant species and coverage of canopy, understorey and herbaceous vegetation. We also consider that the determination of possible edge effects via proximal land uses in riparian corridors would be of extreme importance for riparian landscape ecology studies and conservation.

We also emphasise the priority of conservation of riparian corridors and their adjacent natural habitats through protection of these ecosystems or through rehabilitation of disturbed riparian areas. For this purpose, we reinforce the possibility raised by Larsen et al. (2010) [

38] of integrating riparian birds’ assemblages as indicators under the Water Framework Directive (WFD), since this programme uses biological measures to assess riverine ecosystems’ ecological status [

82].