Abstract

Due to the increase in recreational demands, the significance of protected areas and forests with recreational potential in forests increased with the demands of nature tourism, which in turn provided new income sources to the forestry industry. In the current study, the economic values of the Uzungöl Nature Park’s lake view, an international tourist destination, were estimated using the hedonic pricing method. In the study, 188 questionnaires were conducted with 89 businesses, and the hedonic price function (HPF) was determined based on the study data collected from the businesses in Uzungöl Nature Park. It was estimated that the mean lake view in-room accommodation price for the hotels in Uzungöl Nature Park was USD 207.38 and the lake causes an increase of $2.8 per square meter and $144.67 in total on the room price of the hotels. The study findings demonstrated that the lake view was a desirable quality for hotel rooms, which is reflected in the prices in Uzungöl. The significant contribution of the lake view to room prices would support the planning and management of protected areas that are usually rich in natural resources. Determining the economic value of the lake view will enable business owners operating in the region or those planning to establish new businesses to make more informed pricing strategies. It will also strengthen hotel owners’ marketing campaigns and enable them to think more rationally about new investments (such as adding rooms or services). Business owners will be able to optimize their rooms based on lake views in order to offer more lake-view rooms to customers. Determining the economic value of the lake view will raise awareness about the protection of natural areas. By investing in eco-friendly and sustainable practices, hotel owners will contribute to the conservation of natural resources. The value estimates determined in the present study would also contribute to the employment of total forest value calculations and resource accounting systems.

1. Introduction

The Industrial Revolution led to radical changes in the protection of nature. These developments established the foundations of the current protected approaches [1]. Although different approaches have been adopted by international and national organizations, laws, and regulations to describe protected areas, 10 protection categories were developed by IUCN in 1972 and implemented by several nations, and a “Red List” that included fauna and flora species under the danger of extinction was determined [2]. Based on the nature protection criteria determined in the 4th World Conference on Protected Areas and National Parks, IUCN classified the protected areas into six categories. The world’s protected area network is constantly changing, and the dynamics of this network are tracked using the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). This database evolved from a list of protected areas first mandated by the United Nations in 1959, and it now informs the key indicators that track progress toward area-based conservation targets. In this capacity, the WDPA illuminates the role of protected areas in advancing a range of international objectives and agreements, including the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Sustainable Development Goals [3]. According to WDPA, there are 269,568 protected areas on Earth, 251,922 of which are terrestrial areas. These lands cover an area of over 20 million km2 and correspond to 15.73% of the total lands on earth [4].

In parallel with the global developments, protected areas were classified for the first time by the National Parks Code No. 2873 in Turkey. The code determined four protected area categories. Among these categories, “National Parks, Nature Parks and Nature Monuments” are protection categories that allow recreational use. Based on code no: 2873, a total of 438 protected areas have been declared so far in Turkey, of which 247 are nature parks. Protected areas cover 1042.719 hectares and correspond to 1.3% of the surface area in Turkey [5].

The nature park landscapes in protected areas provide numerous social and psychological benefits such as low stress, emotional and spiritual motivation, and better human relations [6]. Furthermore, certain studies reported that allowing accommodation facilities (hostels, hotels, motels, etc.), picnicking, and safari tours in protected areas, in addition to activities such as trekking and camping significantly contribute to the national economy [7].

Most of the services available in protected areas due to their esthetic properties are environmental assets that provide external benefits to society; however, these do not have a net market price or a market in the traditional sense [8]. Goods and services without a market are considered a source of market failure due to their external benefits and public good or service properties [9]. Internalization of externalities is a preferred method for the solution of this problem in the public economy [10]. To internalize the externalities, goods, and services without a market could be priced. In recent years, an increasing body of scientific and economic research using and supporting ecosystem service valuation is consistent with the increasing efforts to determine the economic value of the non-market benefits of the forests [11].

Forests are among the world’s most productive, diverse, and functionally critical ecosystems [12]. Ecosystem services of forests, including recreational, carbon sequestration, hydrological, and erosion prevention functions, are called the indirect use values. Generally, these services are not accepted as market goods and have no monetary value. However, this does not mean that these functions of the forests are economically worthless [13]. Various economic valuation methods were developed to calculate the monetary value of natural resources, especially that of non-marketable goods and services. In a theoretical market, where environmental goods are traded, the benefits and costs associated with these goods and services are questioned. This approach accounts for personal preferences, individual market behavior, and preferences [14]. A commonly adopted method is the hedonic price method (HPM).

HPM is a valuation method based on disclosed preferences. This method was based on the indirect disclosure of preferences in representative markets for the value of each commodity [15]. HPM is derived from the qualitative value theory and it was demonstrated that a commodity with a market could be considered as a bundle of attributes at its core [16]. The hedonic price model analyzes the effect of a good or service on its price, and it aims to determine the effect of additional features of the goods or services based on the model [17]. HPM adopts a process that would reveal the environmental quality and economic significance associated with the externalities created by public spaces [18]. Thus, the effects of urban green areas, national parks, and forests on housing prices could be estimated with the HPM.

Tyrväinen and Miettinen [19] used the HPM to examine the impact of environmental characteristics on real estate prices. Along with variables such as age, size, number of floors, and presence of a kitchen in the buildings, environmental features like proximity to forests, recreational areas, and the city center were also considered. Their study found that the contribution of green spaces to real estate prices was 4.88% of the total value of the property. They obtained significant findings that demonstrate how such natural beauties affect the local economy and the real estate market. Butsic et al. [20] investigated the impact of recreational value on housing prices in ski resorts. The study calculated the impact based on variables such as the size of the properties, the age of the buildings, the distance to ski resorts, and the decorative condition of the properties. The results of the study found that the recreational value had an average positive impact of 5.32% on housing prices. Zhang et al. [21] used the hedonic pricing method to investigate the impact of public green spaces on real estate prices. The study found that properties located 850–1604 m away from parks saw an increase in sale prices ranging from 0.5% to 14.1%. Wu et al. [22] used the hedonic pricing method to investigate the average effect of green spaces on housing prices. The study found that proximity to green spaces contributed 0.041% to the increase in housing prices. Liebelt et al. [23] investigated the impact of urban green spaces on housing prices, using variables such as the size and age of the properties, the condition of kitchens and bathrooms, proximity to forests, and the distance to parks and the city center. The results of the study found that a 1% increase in green spaces led to an increase in €1.52 to €14 in the price per square meter of the apartments. Irvine et al. [24] used the hedonic pricing method to investigate urban water management, water-sensitive urban design, and enhanced community livability. The study found that properties located closer to areas with water-sensitive urban design had higher sale prices. Kovacs et al. [25] investigated the impact of tree canopy on home values using the hedonic pricing method. They selected variables such as forest presence, size, density, distance to forest, as well as the age, size, and type of properties from the 157 variables obtained from 21 studies. The study found that a 1% increase in tree canopy raised the total value by $557.083 or $277 per acre. Ben et al. [26] used a spatial hedonic pricing model to measure the value of access to green spaces in the housing market of Shanghai. The study found that a 1% increase in overall green space accessibility led to an average 0.17% increase in housing prices, while a 1% increase in the proportion of green space within a housing complex resulted in a 0.46% increase in property prices. Chen et al. [27] used the hedonic pricing method and concluded that in urban planning and landscape design processes, not only the size of green spaces but also their shape and arrangement should be considered. The study used variables such as age, size, bathroom condition, room types, distance to the city center, landscape area size, and landscape characteristics of the properties. They found that a one-unit increase in the landscape shape index could increase housing prices by 4% ($826). Gaižauskienė [28] in her study investigated the impact of urban green spaces on housing prices through research conducted worldwide. The study used the hedonic pricing method to estimate the monetary value of open green spaces on housing prices, focusing on noise and pollution in these areas. Kovacs and Rider [29] analyzed the economic value of groundwater levels (saturation thickness) on agricultural land in Arkansas using the hedonic pricing model. The study found that as groundwater thickness increases, agricultural land prices also increase. A 1-foot increase in saturation thickness raised the average land value by $8.96/foot. Additionally, as the groundwater quantity decreases, the value of the land decreases. They found that when the groundwater level of a property with 120 feet of groundwater drops to 100 feet, the land value decreases by an average of $148 per 0.4047 hectares. Kuroda and Sugasawa [30] examined the impact of scattered green spaces within the city (street trees and garden shrubs) on housing prices using the hedonic pricing method. The study found that a 10% increase in green space density within a 100 m radius resulted in a 2% to 2.5% increase in the prices of for-sale apartments. Peng et al. [31] investigated the impact of different types of urban blue spaces (lakes, large rivers, small rivers) on housing prices in eight major cities in China (Beijing, Chengdu, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Kunming, Shenyang, Suzhou, and Wuhan). The study found that housing prices near lakes were 2.07% to 7.96% higher, while properties near major rivers (large rivers flowing through the city) saw an increase in housing prices by 3.66% to 10.07%. Ke et al. [32] used the hedonic pricing model to investigate the impact of different ecological landscapes (lakes, rivers, mountains, and parks) on housing prices in Wuhan. The study found that if the distance to lakes exceeded 2 km, housing prices increased by 3.39%, while proximity to parks within 2 km resulted in a 43.12% increase in housing prices. Duan et al. [33] created a model using the hedonic pricing method to analyze the value increase in urban park green spaces on housing prices. The study found that park areas increased housing prices by 297,400 CNY/hm2·a ($4.10) per square meter. Mitsis [34] analyzed the impact of holiday subsidies implemented in Cyprus during the COVID-19 pandemic on hotel room prices using the hedonic pricing model. The study found that rooms with a sea view were 5.2% more expensive compared to rooms without a view. Mountain-view rooms were 2.7% more expensive, and garden-view rooms were 2.9% more expensive. Setiowati et al. [35] used the hedonic pricing model to measure the economic value of urban green open spaces in Jakarta and analyze their impact on land prices. The study found that city forests increased prices by 17.1% at a distance of 500–1000 m, and the price increase rose to 19.2% at a distance of 1000–2000 m. Liu et al. [36] analyzed the impact of urban green spaces on housing prices in Beijing using the hedonic pricing method. The study found that each additional hectare of green space within a 400–500 m radius increased housing prices by an average of $8.17/m2.

The articles mentioned above generally investigate the impact of natural resources on hotel or residential prices. The variables examined include the size, age, and floor level of the properties, room type, proximity to parks, lakes, and city centers, as well as the presence of amenities such as bathrooms and kitchens. Additionally, the degree of visibility of resource values (such as lakes, seas, oceans, forests, and recreational areas) has been considered.

In the present article, the economic value of the lake was calculated from the prices of rooms with and without a lake view in hotels located in this study area. In the study, the effect of the lake, the value source for the nature park, on accommodation prices was determined, and its economic value was estimated with HPM based on various landscape attributes of the lake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area and Field Data Collection

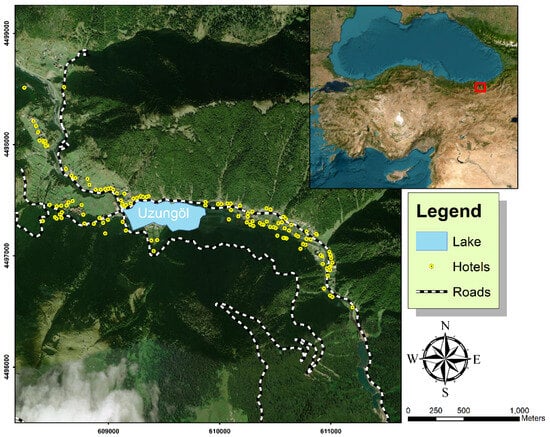

With the development of global ecotourism in the 19th century, new local and regional development opportunities emerged in Turkey, a country with natural and cultural potential. Uzungöl Nature Park, located in Trabzon province in the Eastern Black Sea Region, is 99 km from the urban center and one of the important tourism regions with natural and cultural assets (Figure 1). In Uzungöl, which is 1090 m above sea level, there are generally low-rise pensions and hotels with wooden structures. The area was declared a Nature Conservation Park in 1989, a “Tourism center” by the Ministry of Forestry in 1990, and a “Special Environmental Protection Area” by the Council of Ministers in 2004 [37]. Uzungöl Nature Park has rich flora and fauna that include forest plant species such as eastern spruce, Eastern Black Sea fir, and beech. Uzungöl tourism center is well known (52.8%) by domestic tourists and is visited by visitors at least a few times a year (72.8%) [38].

Figure 1.

Uzungöl Natural Park.

The number of domestic and foreign tourists who visited Trabzon was 1,766,094 in 2018, and 625,564 tourists visited the Uzungöl Natural Park [39]. This figure was 639,859 in 2019. With the political events in Saudi Arabia and the effect of COVID-19, there has been a decrease in the number of tourists until 2022. As a result of positive developments both in COVID and between Turkey and Saudi Arabia, 842,361 tourists visited Uzungöl Natural Park in 2022. According to the official records of the Governorship of Trabzon, a total of 2,852,574 people visited Uzungöl in 2023, and approximately 7 million tourists visited Uzungöl in 2024. In 2023, the number of tourism-certified accommodation establishments in Trabzon increased by 41.67%, and in 2024, it increased by 20%. It was determined that foreign tourists who visited the nature park were predominantly Arabs. The increase in the number of tourists visiting the nature park led to the number of hotels and other facilities in the region.

There are 115 active businesses in Uzungöl. However, in Uzungöl Tourism Center, which is quite short in accommodation facilities, the number of newly constructed homes significantly increased (91%) during the last 35 years, and these homes were used for the accommodation of tourists [40]. The prices of the hotel rooms are determined by the hotel owners, business managers, assistant managers, and marketing managers according to the demands of the tourists and the conditions of the tourism season. Therefore, a survey was developed to collect the HPM data in the study, and the study data were collected through face-to-face interviews with active business owners, business managers, assistant managers, and marketing managers in 2019 August–October. Tourism activities in Uzungöl Nature Park take place between June and October both before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The peak of the season is in August. In both the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods, tourists visiting the region primarily come from Middle Eastern and Arab countries. The most significant factor determining the five-month tourism season is the school schedules (holiday periods) of the tourists’ children visiting the region. Therefore, the data collection period from August to October reflects the peak of tourism activity. Tourism activities in the region are nearly nonexistent during the November–April period. The reasons for this situation are the insufficient number of tourists and challenging climatic conditions. Due to the aforementioned reasons, businesses in the region do not operate during the November–April period. However, during this period, businesses provide limited services to domestic tourists on a day-trip basis. The survey form, Google Earth images, photographs, and basic statistical data on the target market constituted the study material. In addition, the dollar rate in the study is 5.67 Turkish Lira (TL), which is the average for August–October 2019 (1 USD = 5.67 TL).

In the study, the number of active businesses in the region was requested from relevant public institutions. However, the number of registered enterprises in the public sector was considerably lower when compared to the number of active businesses in Uzungöl. For more accurate findings, the number of businesses registered in Çaykara Municipality, which includes Uzungöl, were employed. Çaykara Municipality data revealed that the number of active businesses in Uzungöl was 115. The sample size was calculated with Equation (1) based on 115 enterprises.

n = (N.p.q.Z2)/[(N − 1).d2 + p.q.Z2]

In the equation, n depicts the sample size, N is the population (115 active businesses), p is the probability of the existence of the measured variable in the population (50%), q is the probability of the non-existence of the measured variable in the population (50%), Z is the Z-test value (1.96) at 95% confidence level, and d represents the margin of error (0.05). In the study, a total of 188 individuals (due to different room types) completed the survey and about 1276 (26 different room types) rooms were available in 89 businesses (n = 89).

Within the scope of this study, an attempt was made to determine the economic value of the lake view by considering the lake’s impact on room prices. Two criteria were taken into account in the sample selection of the study, based on the literature review and our observations. The first of these is the distance of the hotels from the lake, and the second is whether the hotel rooms have a view of the lake. As part of this study, a total of 188 questionnaires were carried out across 89 businesses using a random sampling technique to minimize potential bias in the sample distribution. Business owners, managers, and operational staff have different perspectives on room pricing. While business owners consider overall strategies and long-term goals, managers determine operational decisions and pricing strategies. The sales and marketing team can observe price changes based on customer demands and market dynamics, while the finance team can evaluate pricing by focusing on costs and profitability. Collecting data from multiple sources within the same business provides a more reliable analysis than relying on the subjective assessment of a single individual. For these reasons, surveys were conducted with multiple individuals within the same business.

In the study, a survey was conducted with business owners, business managers, assistant managers, and marketing managers. Due to their continuous collection of feedback from customers, they have a broad perspective on the quality of room views. Business owners and managers are better able to assess factors such as the physical location, orientation of the rooms, and environmental obstacles (buildings, trees, etc.) compared to tourists. Room views play a critical role in hotel pricing, and business owners and managers integrate this factor into their pricing strategies. Business owners and managers have a long-term perspective on the hotel’s rooms and surrounding environment. Tourists, due to their short stays, may focus on immediate experiences and make subjective assessments based on their personal expectations For these reasons, business owners and managers can assess the quality of room views from a broader perspective, and these data can provide a more consistent foundation for pricing, marketing strategies, and customer satisfaction.

2.2. Method

The study was conducted with business owners and managers in Uzungöl, where questionnaires were administered to 2 chain hotels, 6 boutique hotels, 25 guesthouses, 44 apart hotels, and 12 bungalow businesses. A questionnaire form containing both open-ended and closed-ended questions was developed as a data collection instrument. This questionnaire form was designed to determine participant demographic information, room sales data, and model room characteristics. The questionnaire consisted of four sections and a total of 36 questions. The first section comprised four multiple-choice questions aimed at identifying the demographic characteristics of the participants. This section collected fundamental information such as the age, gender, educational background, and duration of business operation of the respondents. The second section included a total of 21 open-ended questions designed to determine the physical characteristics of both the interior and exterior of the rooms. Among these, 12 questions focused on the interior physical attributes of the rooms, covering aspects such as room size, flooring materials, furniture type, bed capacity, bathroom features, and heating and cooling systems. The remaining 9 questions aimed to assess the external physical attributes of the rooms, including the type of building in which the rooms were located, the material of the building’s exterior facade, the building’s age, the number of floors, the presence of balconies, and other exterior features. The third section consisted of 8 open-ended questions related to the geographical location of the rooms. This section examined factors such as the distance of the rooms from Uzungöl, their proximity to major transportation routes, and whether they had a direct view of the lake. The fourth section included 3 Likert-type questions designed to assess the view characteristics of the rooms. These questions evaluated whether the rooms had views of the lake, forest, or the general natural surroundings. Additionally, a six-point Likert scale (“none”, “very little”, “little”, “moderate”, “good”, and “very good”) was used to assess the quality of the forest and lake views. The questionnaire form was created based on the studies in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies and variables.

In order to increase the applicability of the study, the Likert scale was used in the visual appearance, similar to the literature. The study was conducted only with business owners (excluding tourists). The Likert scale was chosen as a powerful tool for evaluating the economic value of the lake view based on room prices, allowing businesses to assess the situation subjectively. This preference was due to several reasons:

- Business owners’ business-oriented focus and limited time made it easier for them to evaluate abstract concepts, such as the view, in a simple manner;

- Enabling the simple evaluation of more abstract concepts, such as the view, and allowing hotel owners to reflect their perceptions of such esthetic elements as specific landscapes (e.g., lake view, forest view, ocean view, etc.);

- Enabling the data collected through the Likert scale to be quantified and allowing for comparisons between groups;

- Allowing hotel owners to determine how elements such as the view influence their business strategies (e.g., increasing the number of lake-view rooms, etc.);

- Enabling us to collect a much wider range of opinions from hotel owners.

The focus of the study is the economic value of the lake view in Uzungöl Nature Park. The collection and analysis of data such as tourists’ demographic characteristics, backgrounds, cultures, and religious beliefs require ethical considerations and a high level of sensitivity (due to economic and political reasons). Instead of generalizing based on the aforementioned characteristics of tourists, the focus was placed on their preferences for the view. This way, cultural or religious prejudices were prevented from affecting the survey results.

The hedonic pricing method is an approach that determines the price of a good or service based on the benefits provided by its component characteristics. Hotel room prices are influenced by various factors, such as location, room size, service quality, and view. In this context, the impact of a lake view on room prices can indirectly help estimate the economic value of the lake. The hedonic pricing method has previously been used to measure the impact of environmental and esthetic elements on prices in the housing market (e.g., beachfront properties being priced higher). Similarly, this method can be used for hotel rooms to analyze the impact of a lake view on prices, which in turn contributes to determining the indirect economic value of the lake. Natural areas like Uzungöl are considered public goods and do not have a direct market price. However, the higher pricing of hotel rooms with lake views reflects the economic value that this natural area holds for individuals. Measuring the impact of a lake view on hotel room prices is considered a scientific and valid method for determining the indirect economic value of Uzungöl. This approach is in line with the fundamental principles of the hedonic pricing method, which enables the economic analysis of public goods through market data.

The resource value of the nature park is Uzungöl. All of the tourists visit the park for Uzungöl. Therefore, the economic value estimation of the nature park should be based on the economic value of Uzungöl. In the study, HPM, an indirect economic valuation method was employed to estimate the economic value of Uzungöl Nature Park. The qualitative property that was employed to determine the impact of the hedonic price method on the composite goods class ’hotel rooms’ and their prices to test the research problem was ’Uzungöl’. Since Uzungöl is a public property, it was not possible to measure the market price directly. However, the physical/social-cultural environmental characteristics of hotel rooms are one of the elements of the individual demand function, in which individuals make choices to maximize their utility. Therefore, room features are one of the elements of the determined price function. This allows the prediction of the visible prices. Due to the difficulty of defining the supply market and the lack of regular archive data, the visible prices in Uzungöl were determined with the HPM [51]. The method was based on the basic principle of the method. The consumer benefits offered by various attributes of a particular product determine the price of that product [52].

Rosen [52] classified each commodity as a coordinate vector based on its attributes in the hedonic price model and expressed it as a constant Zi. In the model, each commodity is depicted as i based on its properties (class = i). When Rosen determined the framework of the market equilibrium in the hedonic price model, he analyzed the short- and long-term equilibrium (where utility maximization is equal to profit maximization) for a heterogeneous commodity under perfectly competitive market conditions. He analyzed differentiated products in a perfectly competitive market model, where consumers maximize their benefits and producers maximize their profits. In Rosen’s market model, goods (Z) are expressed as the sum of their property n. Thus, the Rosen [52] model is expressed as follows:

Zi = (Z1, Z2, ……, Zn)

Consumers’ personal evaluations of alternative packages could differ. Thus, consumers are offered various property combinations. The presence of different products means several property vectors. Each product has a market price, and therefore, it is associated with the constant value of the Z vector. Thus, the demand function for the product in the market is

P(z) = p (z1, z1, ……, zn)

This function is equivalent to the hedonic price regression obtained by comparing the prices of commodities with different properties. This provides the minimum value of any property package. If sellers sell the same package at different prices, consumers will prefer the cheaper product independent of the seller. Thus, it is necessary to take the partial derivatives of Equation (3) to determine the effect of each property on the price. Therefore, the value associated with each property could be determined.

When this equation is applied to each variable, it would reflect the marginal implicit price of that property. The sum of implicit prices would give the hedonic price of the commodity [53].

Pzi = ∂P/∂Zİ

In the study, hotel/motel/pension rooms were accepted as composite commodities, and room prices that include the implicit prices of room properties were used as the composite commodity prices. In the hedonic price model, it was accepted that the room prices were a function of the property groups that included the internal and external structural room properties, the qualitative and quantitative accessibility criteria, and the lake–forest view alternative.

- Internal Properties: Room type, number of rooms, age, area, room sections such as kitchen, balcony, flooring, heating, and bathroom;

- External Properties: Availability of a laundry, parking lot, playground, security, pool, open green area in the building where the accommodation unit is located (apart-detached), the number of meals served, hotel season, hotel shuttle, agency agreements, advertisement type;

- Accessibility: Distance to the lake, the forest, the shopping center, restaurants, picnic areas, observation hill, the main road, and social activities;

- The View: Elements of the room view, the physical properties of the lake/forest and other green area views, the quality of the lake/forest view, and the most important landscape element.

The surveys and data collection were conducted in 89 businesses and hedonic analyses were based on 188 observations. SPSS 23.0 software was used in multiple regression analysis to process the survey data, digitize the qualitative data, and determine the variables and HP functions.

In the study, various hedonic price functions are derived with semi-logarithmic functions and variables for different lake–forest view attributes:

ln[P(z)] = α0 + ∑ βi STRUCTURALi +∑ βu ACCESSIBILITYu + ∑ βm VIEWMm+ ε

The implicit prices (marginal payment trends) for the lake–forest view attributes included in the above function, hence the economic value estimates, were calculated as follows:

∂P⁄∂Zİ = βM.P

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

In the study, 188 individuals were surveyed in 89 businesses. The demographics of these participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant demographics [54].

It was determined that 85.6% of the participants were male and 58% of the participants were married. The participant age varied between 17 and 69, and the mean age was 34. About 45.7% of the participants were high school or higher education graduates. Of the survey participants, 30 were business owners, 19 were business managers, 22 were assistant managers, and 18 were marketing managers. Business managers had held the same position for an average of 7.8 years, assistant managers for 3.4 years, and marketing managers for 4.6 years. In the study, surveys were conducted with one person in 36 businesses, two people in 40 businesses, and three people in 24 businesses.

3.2. Findings on the Hotels

The room price varied between USD 52.91 and 440.92 and the mean room price was USD 200.38. The total number of rooms in the participating businesses was 1276, and the mean number of rooms was 6.79. The rooms were 16–120 square meters, and the mean room size was 51.7 square meters. The age of the hotel buildings varied between 1 and 45 years and the mean hotel age was 6.64. The hotel season was about 8.52 months.

The review of the physical properties of the hotels revealed that 55.9% of the rooms had a kitchen, 83.5% had a balcony, and almost all had private security (98.4%) and parking (96.8%). Children’s playgrounds were available in 28.7% of the hotels, while 58.5% had green areas, and 86.7% worked with tourism agencies.

The findings revealed that there were 26 room types. The most common type was standard rooms for a maximum of two guests (17%), followed by four rooms (9.6%), two rooms (9%), and one room (7.4%). The rarest rooms were apart suites, apart doubles, junior apart suites, terrace suites, deluxe suites, king beds, honeymoon suites, and villa duplexes.

In the study, it was determined that only 62.8% of the 26 room types had bathrooms, 86.2% had parquet flooring, and 63.3% were heated with wood-coal stoves. Furthermore, only 4.8% of the hotels had pools or spas, and 67.6% of the hotels advertised only on the internet.

The distance of the hotels to the forest varied between 10 and 500 m and the mean distance was 37.23 m. The mean distance between the hotels and the observation hill was 475.53 m.

The criteria employed in 188 surveys conducted with 89 businesses included lake view, forest view, and forest + lake view. The analysis revealed that all 26 room types had forest views. Since all rooms had forest views, rooms with lake views also had forest views. Thus, 44.7% of the rooms (570 rooms) had both forest and lake views.

The owners of each business were asked whether the rooms could see the lake. A 5-point Likert scale was used to determine the lake visibility of the rooms. The analysis of the view quality of the rooms revealed that all room types with forest view had a very good view rating. In total, 44.7% of all rooms had lake views, and the same analysis revealed that 2.4% of these rooms had poor, 1.2% had low, 11.9% had moderate, 9.5% had good lake views, and 75% had very good lake views. The analysis of the rooms with forest + lake view revealed that since all rooms had forest view, rooms with lake view also had forest view.

3.3. Hedonic Price Functions

Three hedonic price functions (HPF) were derived based on different variables that reflected Uzungöl Natural Park properties. The HPF definitions, descriptive statistics, and hotel attribute codes are presented in Table 3. Although there were statistically significant correlations between several variables that were derived from the view and other hotel properties and the individual room prices, these were not reflected in the HPF significantly in multiple regression analyses due to autocorrelation.

Table 3.

Variables and descriptive statistics [54].

In the study, the main reason for distinguishing between rooms with a forest + lake view and those with a lake view is to analyze these two elements (forest and lake) separately and to understand each of their effects on the value of the view. Likewise, the economic value of a forest and lake view may differ from that of a lake view alone. Therefore, in order to clearly identify the advantages offered by such rooms and to contribute positively to the analyses, forest and lake views have been considered separately. However, although this aspect was taken into account in the study, the descriptive statistics of rooms with a forest + lake view and those with a lake view were found to be similar.

The average price of rooms without a lake view is $193.38. For rooms with a lake view, the room price is $207.38. All rooms in the establishments in Uzungöl Nature Park had a forest view. Thus, the HPF was not calculated for the rooms with a forest view. The HPF for the room lake view variable (RLKV) is presented in Table 4. Logarithmic transformation was performed for all variables.

Table 4.

Variations and descriptive statistics [54].

The HPF for the room lake view variable (RLKV) is

RLKV= 2.649 + 0.821 × (RSIZ) + 0.146 × (RTYP) + 0.255 × (LNDRY) + 0.196 × (HPRK) + 0.313 × (HGRSPC) + 0.275 × (HDISPCNC) + 0.154 × (QLKV)

In the study, the HPF was determined for the lake view variable of the enterprises that operate in Uzungöl Nature Park. This HPF was significant at the 95% level and reflected 84% of the room rates. The autocorrelations for all independent variables were as expected.

3.4. Economic Value Estimates

Multiplication of the coefficient of each independent variable in the semi-logarithmic model by the mean room price gave the marginal implicit price of a unit with the relevant attribute. The implicit prices calculated based on the average room price for each unit with RLKV are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Economic value estimation for lake view in Uzungöl Nature Park [54].

The economic value of the lake was estimated based on the effect of the lake view on the room price. Table 5 reflects the contribution of Uzungöl, the source value, to the room prices with a lake view in Uzungöl Nature Park. The mean room price in the table was based on Table 3, and the β value (QLKV) was based on Table 4. Thus, the marginal implicit price of the rooms (USD 31.94) with a lake view was calculated with the multiplication of the β value (0.154) by the mean room price (USD 207.38). The multiplication of the marginal implicit price of the rooms with lake view by the mean lake view degree coefficient (4.53) for the QLKV variable in Table 3 revealed the lake view value per room (USD 144.67). The total number of rooms in Uzungöl was 1620, and approximately 45% (729 rooms) had lake views. The calculation of the view value per room for all rooms overlooking the lake revealed that the total lake view value was USD 105,464.43.

4. Discussion

Since the benefits of public spaces such as protected areas are not an economic output but social benefits observed in living standards, it would be impossible to directly measure their economic values [55]. However, there are indirect measurement methods [56]. HPF is one of these methods, and it is a common method for the economic valuation of environmental commodities such as protected areas [57]. Calculation of the economic value of these assets and determination of their role in national income with the most accurate method with an approach that prioritizes the ecosystem with HPF is important to create an investment base in these areas [58].

The study area, Uzungöl, has high tourist value. Atasoy [40] reported that the number of domestic tourists who visited Uzungöl Tourism Center between 2005 and 2009 was 667,628 and the number of foreign tourists was 17,479. Künü et al. [59] reported that the number of foreign tourists in Trabzon was 450,935 in 2012 and all foreign tourists also visited Uzungöl, demonstrating the significant interest of domestic and foreign tourists in the region. The increase in the number of tourists who visited the Uzungöl region was due to the increase in the number of hotels. In the tourism sector, there is typically a strong correlation between the increase in accommodation capacity in a region and the rise in the number of visitors. The growth in the number of hotels in Uzungöl indicates the development of the region’s tourism infrastructure and its ability to accommodate more tourists. Some key observations that support this type of relationship are as follows: The increase in accommodation facilities in a region allows more tourists to visit the area. A region that was previously able to host a limited number of tourists due to inadequate accommodation can serve a larger visitor base with the opening of new hotels. In popular tourist areas, typically, the flow of tourists begins first, and accommodation capacity is increased based on this demand. However, in some cases, infrastructure investments (such as new hotels, transportation facilities, etc.) can also trigger an increase in the number of tourists.

Statistical methods (such as regression analysis, Granger causality test, etc.) may be required to definitively prove this type of relationship. However, the parallel increase observed in the annual hotel numbers and tourist figures in the region makes such an interpretation reasonable. The study observes that the number of hotels in Uzungöl has increased over the years, and a significant rise in the number of tourists has also been noted during the same period. In this case, it can be inferred that the increase in the number of hotels may have contributed to the rise in the number of tourists. Although this inference does not prove a direct causal relationship, it is consistent with general trends in the tourism sector. Studies in the literature on tourism economics and destination management typically show that the development of tourism infrastructure leads to an increase in the number of visitors. Crouch and Ritchie [60] in their destination competitiveness model, emphasize that accommodation capacity is one of the key factors that enhances the tourism appeal of a region. Studies have also found that the development of tourism infrastructure and the increase in accommodation capacity have positive effects on the number of tourists and economic performance [61,62,63,64]. The increase in the number of tourists had a positive impact on the increase in the number of businesses (115 hospitality businesses) and the diversification of these businesses (26 room types). It was determined that the number of rooms in active tourism facilities in Uzungöl corresponds to about 13% of the total rooms in the Eastern Black Sea Region. Kizilirmak et al. [65] concluded that the total number of hotels, motels, hostels, and camping facilities in Uzungöl was 105, and these businesses had 1135 rooms. Similar to the study, it was determined that the number of hospitality businesses in Uzungöl was 115 and these hosted 1620 rooms. This revealed that Uzungöl is a popular rural tourism region. Gülpınar et al. [38] reported that Uzungöl is the most well-known and visited area in Trabzon due to internet advertising, which is also determined as the most preferred form of advertising by local businesses in the region in our study. The mean room size with a lake view was more than twice the mean room size (25 m2) in chain hotels in Turkey [66].

HPF has been used to estimate the economic value of environmental commodities and services based on the impact of certain facilities such as forests, protected areas, urban forests, parks, botanical parks, and other environmental properties such as lake, sea, and ocean view on housing, rental, and room prices.

In HPF studies, various criteria such as ocean view Hamilton [67], Latinopoulos [68], Mendoza-González et al. [69], Scorse et al. [70], Pearson et al.’s [71], forest view Kaya and Özyürek [8], presence of trees Mei et al.’s [72], Siriwardena et al.’s [73], number of trees Melichar and Kaprová [74], Donovan and Butry [75], presence of green spaces Bottero et al.’s [76], Łaszkiewicz et al.’s [77], Czembrowski and Kronenberg [78] have been used, while in the present study, lake view was used, similar to Nelson [79].

In the study, the lake view variable, a property that determines the room price, was analyzed to measure its impact on the room prices in hotels, motels, and hostels in Uzungöl, and its impact on the price was determined. The HP functions derived with the quantitative and qualitative variables to determine the esthetic benefits of Uzungöl Lake’s view revealed that the value of the lake view was USD 144.67 per room and USD 2.80 per square meter. Petric and Mandić [80] calculated the impact of the location and nature-protected area properties on room prices with the hedonic price method and reported that the mean single room price was €37 (USD 43.7). In the present study, it was concluded that the mean room price in Uzungöl Nature Park was USD 207.38. The fact that Arab tourists have preferred the region in recent years led to the exorbitant price difference between the mean room prices. Kaya and Özyürek [8] reported that the forest view had an impact of 5.14%–7.3% on mean house price, and Pearson et al. [71] reported that the Noosa ocean view had a 76% positive effect on housing prices. Similarly, the impact of the lake view on room price was 69.7% in the current study.

Kaya and Özyürek [8] determined that the contribution of urban forest view to housing prices was about USD 7065.47. Latinopoulos [68] reported that sea view rooms had higher prices when compared to rooms without sea view, Hamilton [67] stated that the effect of sea view on room price was € 12.436 (USD 15.21), Laverne and Winson-Geideman [81] reported the approximate effect of view on rental prices as 7%. Since all rooms in Uzungöl Nature Park had a forest view, the HPF was not determined for the rooms with a forest view. However, the HPF determined for rooms with a lake view revealed that the presence of a lake view increased the room price by USD 144.67 (69.7%), and the total value of the lake view was USD 105,464.43.

In HPF studies, generally the distance to the urban forests, lakes, rivers, parks, and other green urban areas Wen et al.’s [82], Gibbons et al.’s [83], Scorse et al.’s [70], Tapsuwan et al.’s [84], Schläpfer et al.’s [85], Latinopoulos [68], Bottero et al.’s [76], A Samad et al.’s [86], Kim et al.’s [87], Panduro et al.’s [88], Łaszkiewicz et al.’s [89]), Loret de Mola et al.’s [90] and the size or the rate of the green areas in addition to the distance A. Samad et al.’s [86] were utilized. However, in the current study, the HPF was not calculated for the distances between the room, the lake, and the forest, since the distances between the hotels and the lake were minimal.

The significance of the lake view variable in the HP functions derived with HPF in the study and related value estimates demonstrated that Uzungöl Nature Park’s lake view was a desirable feature for the rooms and its esthetic benefits were reflected in room prices. The fact that the lake view contributed to room prices revealed the significance of the resource value in protected areas. The value estimates obtained in the current study were consistent with those reported in the literature.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study lead to three primary conclusions that have important legal, ecological, and economic implications.

Legal Implications:

The study found that businesses operating in the region often lack formal registration with the relevant public institutions. This situation results in lower tax revenues for public institutions, underemployment, and insufficient supervision. Theoretically, this finding underscores the need to revisit regulatory frameworks to better integrate informal sector activities. Practically, policymakers should design targeted registration and oversight strategies that could improve public revenue and ensure compliance.

Ecological Implications:

The observed increase in the number of visitors to the Uzungöl region, although reflecting its growing popularity, appears unplanned and unscheduled. This surge has led to the exceeding of the natural park’s carrying capacity, adversely affecting local wildlife and contributing to environmental pollution and vegetation destruction. Theoretically, these findings contribute to the literature on sustainable tourism by highlighting the ecological risks of rapid tourism growth. Practically, local and regional authorities are urged to implement sustainable tourism management practices, including visitor quotas and improved environmental monitoring, to protect the ecological integrity of the area.

Economic Implications:

Economically, the study reveals that the presence of Uzungöl contributes to an increase in.8 per square meter and a total of $144.67 on average in hotel room prices. Although such price increments are inevitable, an examination of the socio-demographic profiles of business owners indicates a generally low education level. Most businesses operate as family-run companies and primarily employ local individuals. While this may support local development, it also suggests that the region’s economic potential is not being harnessed effectively or efficiently. Moreover, the challenges in accurately accounting for these economic values represent a significant loss to both the regional and national economies. Theoretically, this highlights a gap in the literature on the economic valuation of protected areas, particularly in emerging markets. Practically, there is a need for enhanced capacity-building initiatives for local businesses and improved data collection methods to capture the true economic contributions of ecosystem services.

One of the primary limitations of this study is its cross-sectional nature, which restricts the ability to establish causality and observe long-term trends. The use of indirect methods, such as the hedonic pricing function (HPF), to estimate the economic value of ecosystem services introduces additional uncertainty. The challenges of data collection further constrain the comprehensiveness of the findings. Future research should employ longitudinal designs and more robust econometric techniques to confirm the causal relationships identified here. Moreover, there is a critical need for further studies that explore the economic valuation of protected areas, especially in regions where data are sparse, to inform both local and national policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.B.; Methodology, M.M.B.; Investigation, M.M.B. and C.D.; Data curation, E.K.; Writing—original draft, M.M.B. and E.K.; Writing—review & editing, Z.C. and C.D.; Supervision, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) (Project code: TOVAG-119O131).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Petrova, S. Communities in Transition: Protected Nature and Local People in Eastern and Central Europe; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-13-825130-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Grodzińska-Jurczak, M.; Brown, G. Conservation on private land: A review of global strategies with a proposed classification system. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, H.C.; Bignoli, D.J.; Lewis, E.; MacSharry, B.; Burgess, N.D.; Visconti, P.; Deguignet, M.; Misrachi, M.; Walpole, M.; Stewart, J.L.; et al. Sixty years of tracking conservation progress using the World Database on Protected Areas. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA); UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- DKMP. Protected Area Statistics. Ankara, Turkey, 2022. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/DKMP/Menu/18/Korunan-Alan-Istatistikleri (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Li, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Innes, J.L.; Ferretti-Gallon, K.; Wang, G. The contribution of national parks to human health and well-being: Visitors’ perceived benefits of Wuyishan National Park. Int. J. Geoheritage Park. 2021, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Brough, P.; Hague, L.; Chauvenet, A.; Fleming, C.; Roche, E.; Sofija, E.; Harris, N. Economic value of protected areas via visitor mental health. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, G.; Özyürek, E. Kent ormanı anlayışıyla ODTÜ Ormanı manzarası için ekonomik değerin tahmin edilmesi. Orm. Arş. Der. 2016, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cunningham, S. Understanding Market Failures in an Economic Development Context; Mesopartner Monograph 4; Mesopartner: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; p. 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, M.Y.; Firidin, E. Economıcal and Fıscal Instruments of Envıronmental Polıcy: A Theorıc Examınatıon on Envrınmental Taxes. J. Life Econ. 2017, 4, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovac, M. The economic value of tourism and recreation across a large protected area network. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Blair, D.; Keith, H.; Lindenmayer, D. Modelling water yields in response to logging and representative climate futures. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsalyamova, S.O.; Khuazhev, O.Z.; Khashir, B.O.; Tkhagapso, M.B.; Bgane, Y.K. The economic value of forest ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2015, 6, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L.O. Hedonics. In a Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Champ, P.A., Boyle, K.J., Brown, T.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 235–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, J.; Wicker, P. Monetary valuation of non-market goods and services: A review of conceptual approaches and empirical applications in sports. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M., III; Herriges, J.A.; Kling, C.L. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Sarantis, N. Price-quality relations and hedonic price indexes for cars in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 1999, 6, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Söderberg, B. Estimating market prices and assessed values for income properties. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Miettinen, A. Property prices and urban forest amenities. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2000, 39, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsic, V.; Hanak, E.; Valletta, R.G. Climate change and housing prices: Hedonic estimates for ski resorts in western North America. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xie, G.; Xia, B.; Zhang, C. The effects of public green spaces on residential property value in Beijing. J. Resour. Ecol. 2012, 3, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Li, W.; Peng, J.; Huang, L. Impact of urban green space on residential housing prices: Case study in Shenzhen. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, 05014023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebelt, V.; Bartke, S.; Schwarz, N. Hedonic pricing analysis of the influence of urban green spaces onto residential prices: The case of Leipzig, Germany. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Choy, B.H.; Chua, L.; Gaut, J.; Ho, H.L.; Tontisirin, N. A hedonic pricing approach to value ecosystem services provided by water-sensitive urban design: Comparison of Geelong, Australia and Singapore. Nakhara J. Environ. Des. Plan. 2020, 19, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K.; West, G.; Nowak, D.J.; Haight, R.G. Tree cover and property values in the United States: A national meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 197, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, S.; Zhu, H.; Lu, J.; Wang, R. Valuing the Accessibility of Green Spaces in the Housing Market: A Spatial Hedonic Analysis in Shanghai, China. Land 2023, 12, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jones, C.A.; Dunse, N.A.; Li, E.; Liu, Y. Housing Prices and the Characteristics of Nearby Green Space: Does Landscape Pattern Index Matter? Evidence from Metropolitan Area. Land 2023, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaižauskienė, A. Impact of green spaces on house prices. Moksl.—Liet. Ateitis/Sci.—Future Lith. 2023, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K.; Rider, S. Estimating the demand for groundwater: A second-stage hedonic land price analysis for the Lower Mississippi River Alluvial Plain, Arkansas. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2023, 55, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Sugasawa, T. The value of scattered greenery in urban areas: A hedonic analysis in Japan. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2023, 85, 523–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z. The Impact of the Type and Abundance of Urban Blue Space on House Prices: A Case Study of Eight Megacities in China. Land 2023, 12, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Yang, C.; Shi, W.; Mougharbel, A.; Guo, H.; Zheng, M. Impact of different ecological landscapes on housing prices: Empirical evidence from Wuhan through the hedonic pricing model appraisal. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2023, 38, 1289–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, B. The Urban Park Green Spaces Landscape Premium Functional Value Accounting System: Construction and Application. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsis, P. Effect of subsidies on hedonic price model: Case of hotel room rates in Cyprus during COVID-19. Acta Tur. 2024, 36, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiowati, R.; Koestoer, R.H.; Andajani, R.D. Valuation of urban green open space using the Hedonic price model. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2024, 10, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, H.; Siikamäki, J.; Xu, J. Area-based hedonic pricing of urban green amenities in Beijing: A spatial piecewise approach. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 1223–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, N. Avalanche susceptibility mapping with the use of frequency ratio, fuzzy and classical analytical hierarchy process for Uzungol area, Turkey. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 194, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülpınar Sekban, D.Ü.; Bekar, M.; Acar, C. Evaluatıon Of Trabzon’s Hıgh Plateau Tourısm Potentıal And Examınatıon From Awareness. J. Intl. Sci. Res. (IBAD) 2018, 3, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, E.; Ödemiş, M. Arap Turistlerin Doğu Karadeniz Bölgesi’ne Ekonomik Katkılarını Belirlemeye Yönelik Betimsel Bir Araştırma. Gaziantep Univ. J. of Soc. Sci. 2020, 19, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Atasoy, M. Monitoring land use changes in tourism centers with GIS: Uzungl case study. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 790–798. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli, A.A. Star Rating and Corporate Affiliation: Their Influence on Room Price and Performance of Hotels in Israel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 214, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Mulligan, G.F. Hedonic Estimates of Lodging Rates in the Four Corners Region. Prof. Geogr. 2002, 544, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinet, J.M.; Saez, M.; Coenders, G.; Fluvià, M. Effect on Prices of the Attributes of Holiday Hotels: A Hedonic Prices Approach. Tour. Econ. 2003, 92, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monty, B.; Skidmore, M. Hedonic Pricing and Willingness to Pay for Bed and Breakfast Amenities in Southeast Wisconsin. J. Travel Res. 2003, 422, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, C. Examining the Determinants of Room Rates for Hotels in Capital Cities: The Oslo Experience. J. Rev. Pricing Manag. 2007, 5, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M. A Hedonic Price Model for Ski Lift Tickets. Tour. Manag. 2008, 296, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Rothschild, R. An Application of Hedonic Pricing Analysis to the Case of Hotel Rooms in Taipei. Tour. Econ. 2010, 163, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ye, B.H.; Law, R. Determinants of Hotel Room Price: An Exploration of Travelers’ Hierarchy of Accommodation Needs. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 304, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigall-I-Torrent, R.; Fluvià, M. Managing Tourism Products and Destinations Embedding Public Good Components: A Hedonic Approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 322, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamel, G. Weekend vs. Midweek Stays: Modelling Hotel Room Rates in a Small Market. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 314, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutluer, D. The Compilation of House Prices Country Examples and an Application for Turkey. TISK Acad. 2008, 3, 240–278. [Google Scholar]

- TÜBİTAK. Economic Value Estimation of Uzungöl Nature Reserve with Hedonic Pricing Method. 2020, Project Code: TOGAV-119O131. Available online: https://trdizin.gov.tr/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Tiebout, C.M. A pure theory of local expenditures. J. Policy Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamwesigye, D. Expressed preference methods of environmental valuation: Non-market resource valuation tools. Preprints.org 2019, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamwesigye, D. Total economic valuation approach of nature: Forests. In Public Recreation and Landscape Protection-with Sense Hand in Hand; Mendelova Univerzita v Brně: Brno, Czech Republic, 2020; p. 524. ISBN 978-80-7509-779-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükbekir, E.; Bayramoğlu, M.M. Comparison of Resource Valuation Methods in Protected Areas. In Conservation of Natural Resources in the Context of Climate Change; Şen, G., Güngör, E., Eds.; Duvar Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Künü, S.; Hopoğlu, S.; Sökmen Gürçam, Ö.; Güneş, Ç. Turizm ve bölgesel kalkınma arasındaki ilişki: Doğu Karadeniz Bölgesi üzerine bir inceleme. Iğdır Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 7, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 443, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Chang, C.P. Tourism Development and Economic Growth: A Closer Look at Panels. Tour. Manag. 2008, 291, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Risso, W.A. Tourism as a Determinant of Long-Run Economic Growth. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 21, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B. Assessing the Dynamic Economic Impact of Tourism for Island Economies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 381, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.H. Impact of Investment in Tourism Infrastructure Development on Attracting International Visitors: A Nonlinear Panel ARDL Approach Using Vietnam’s Data. Economies 2021, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılırmak, İ.; Kaya, F.; Şişik, L. Kırsal turizm açısından Doğu Karadeniz Bölgesi’ndeki konaklama işletmelerinin incelenmesi. Intl. J. Soc. Econ. Sci. 2014, 4, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Üstündağ, H.; Işık, S. Antalya Bölgesinde Otel Oda Fiyatlarının Tahmini. Sey. Ot. İşlet. Derg. 2018, 15, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.M. Coastal landscape and the hedonic price of accommodation. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, D. Using a spatial hedonic analysis to evaluate the effect of sea view on hotel prices. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Gonzalez, G.; Martinez, M.; Guevara, R.; Perez-Maqueo, O.; Garza-Lagler, M.; Howard, A. Towards a sustainable sun, sea, and sand tourism: The value of ocean view and proximity to the coast. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorse, J.; Reynolds, F., III; Sackett, A. Impact of surf breaks on home prices in Santa Cruz, CA. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.J.; Tisdell, C.; Lisle, A.T. The Impact of Noosa National Park on Surrounding Property Values: An Application of the Hedonic Price Method. Econ. Anal. Policy 2002, 32, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Hite, D.; Sohngen, B. Demand for urban tree cover: A two-stage hedonic price analysis in California. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 83, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena, S.D.; Boyle, K.J.; Holmes, T.P.; Wisemand, P.E. The implicit value of tree cover in the U.S.: A meta-analysis of hedonic property value studies. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 128, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melichar, J.; Kaprová, K. Revealing preferences of Prague’ s homebuyers toward greenery amenities: The empirical evidence of distance—Size effect. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, G.H.; Butry, D.T. Trees in the city: Valuing street trees in Portland, Oregon. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Caprioli, C.; Foth, M.; Mitchell, P.; Rittenbruch, M.; Santangelo, M. Urban parks, value uplift and green gentrification: An application of the spatial hedonic model in the city of Brisbane. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, E.; Heyman, A.; Chen, X.; Cimburova, Z.; Nowell, M.; Barton, D.N. Valuing access to urban greenspace using non-linear distance decay in hedonic property pricing. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 53, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czembrowski, P.; Kronenberg, J. Hedonic pricing and different urban green space types and sizes: Insights into the discussion on valuing ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 146, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.P. Valuing rural recreation amenities: Hedonic prices for vacation rental houses at deep creek lake, Maryland. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2010, 39, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Petrić, L. The impacts of location and attributes of protected natural areas on hotel prices: Implications for sustainable tourism development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 833–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverne, R.J.; Winson-Geideman, K. The influence of trees and landscaping on rental rates at office buildings. J. Arboric. 2003, 29, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Assessing amenity effects of urban landscapes on housing price in Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, S.; Mourato, S.; Resende, G.M. The amenity value of english nature: A hedonic price approach. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2014, 57, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsuwan, S.; Polyakov, M.; Bark, R.; Nolan, M. Valuing the Barmah–Millewa Forest and in stream river flows: A spatial heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent (SHAC) approach. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 110, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schläpfer, F.; Waltert, F.; Segura, L.; Kienast, F. Valuation of landscape amenities: A hedonic pricing analysis of housing rents in urban, suburban and periurban Switzerland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 141, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Samad, N.S.; Abdul-Rahim, A.S.; Mohd Yusof, M.J.; Tanaka, K. Assessing the economic value of urban green spaces in Kuala Lumpur. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 10367–10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, G.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, G. Understanding the local impact of urban park plans and park typology on housing price: A case study of the Busan metropolitan region, Korea. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 184, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panduro, T.E.; Jensen, C.U.; Lundhede, T.H.; von Graevenitz, K.; Thorsen, B.J. Eliciting preferences for urban parks. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 73, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, E.; Czembrowski, P.; Kronenberg, J. Can proximity to urban green spaces be considered a luxury? Classifying a non-tradable good with the use of hedonic pricing method. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loret de Mola, U.; Ladd, B.; Duarte, S.; Borchard, N.; Anaya La Rosa, R.; Zutta, B. On the Use of Hedonic Price Indices to Understand Ecosystem Service Provision from Urban Green Space in Five Latin American Megacities. Forests 2017, 8, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).