Development of an Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects Through a Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

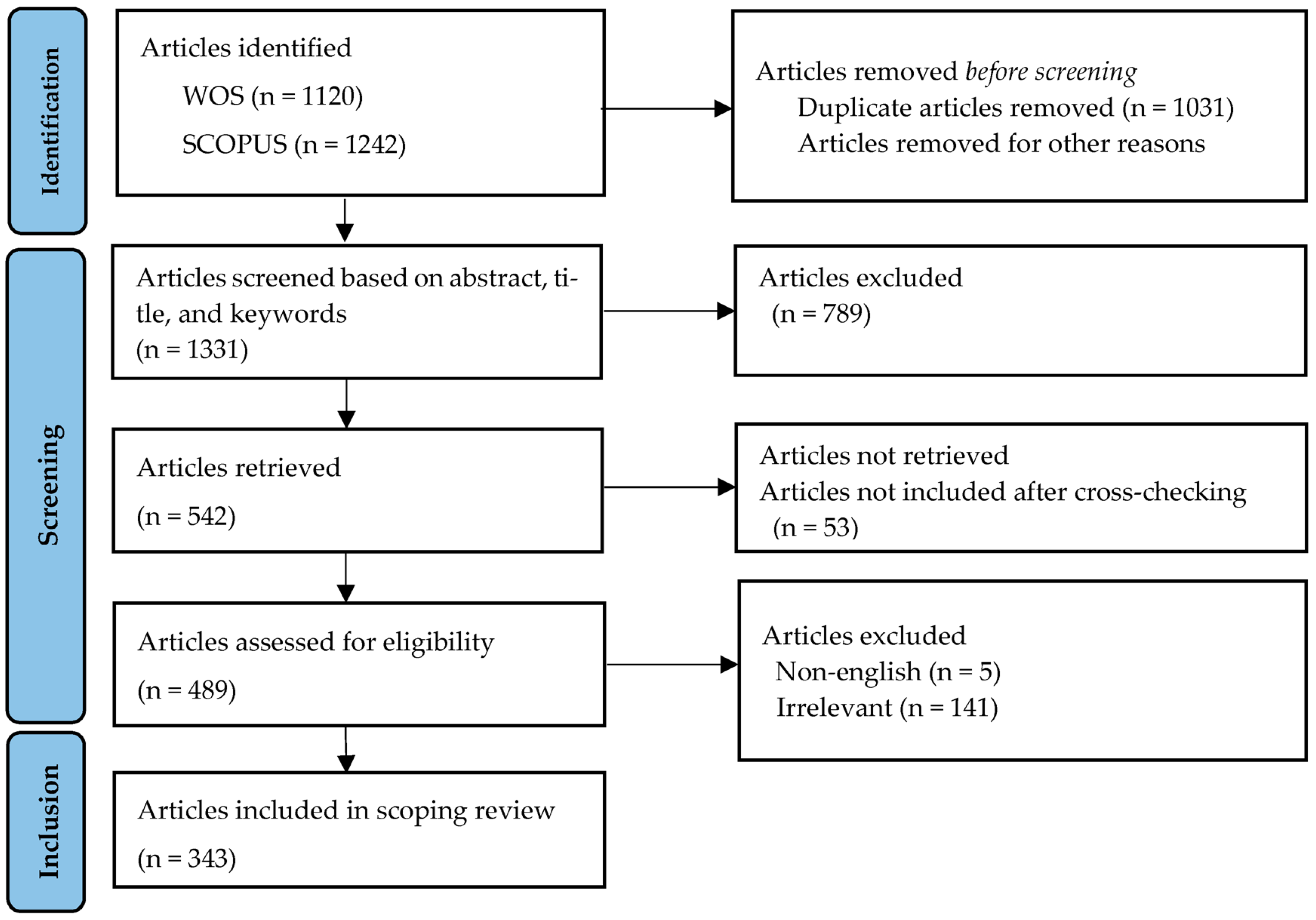

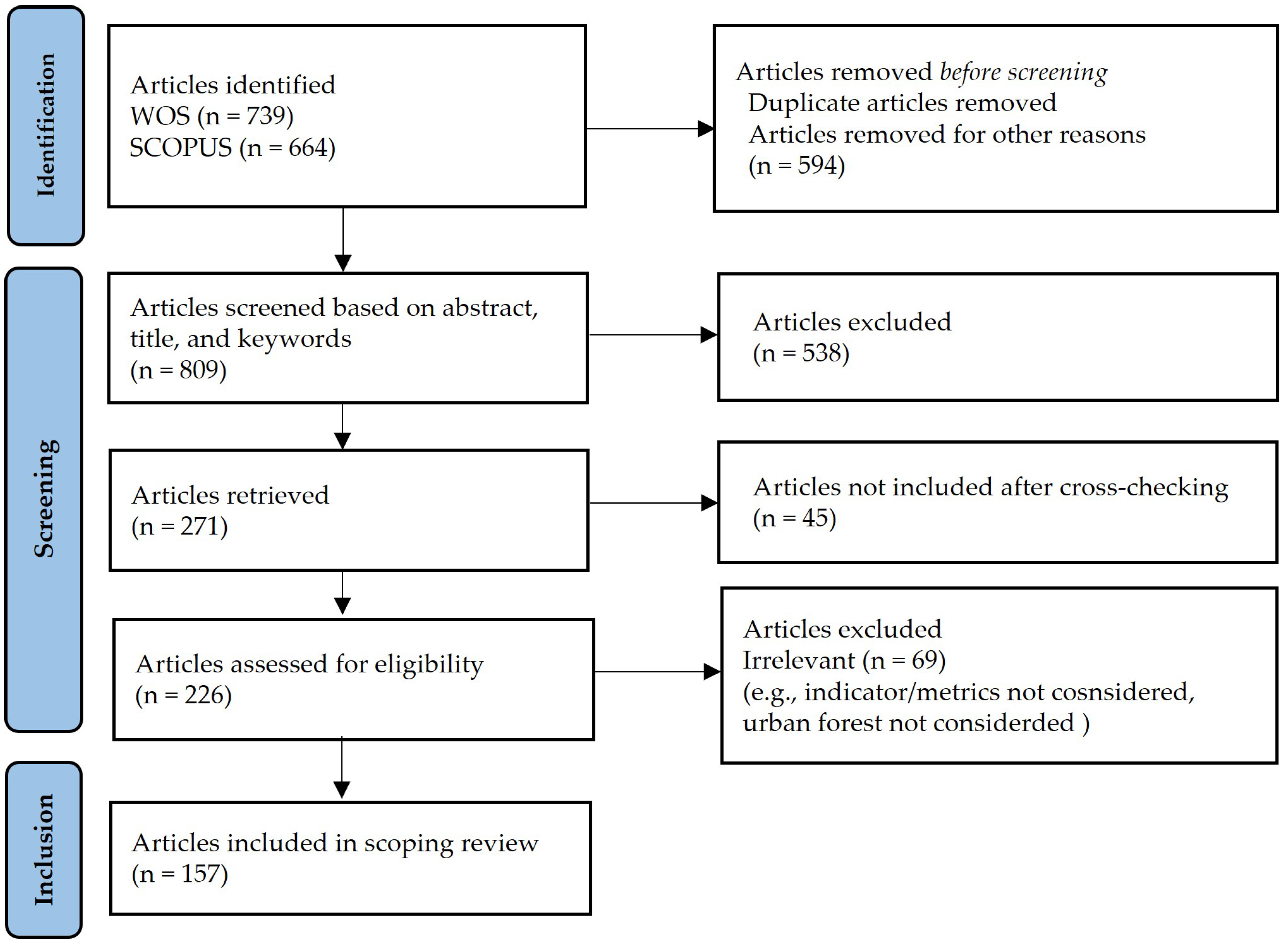

2.1. Scoping Review Process

2.2. Urban Forest Effect Classification and Indicator Identification

2.3. Indicator Assessment Framework

3. Results

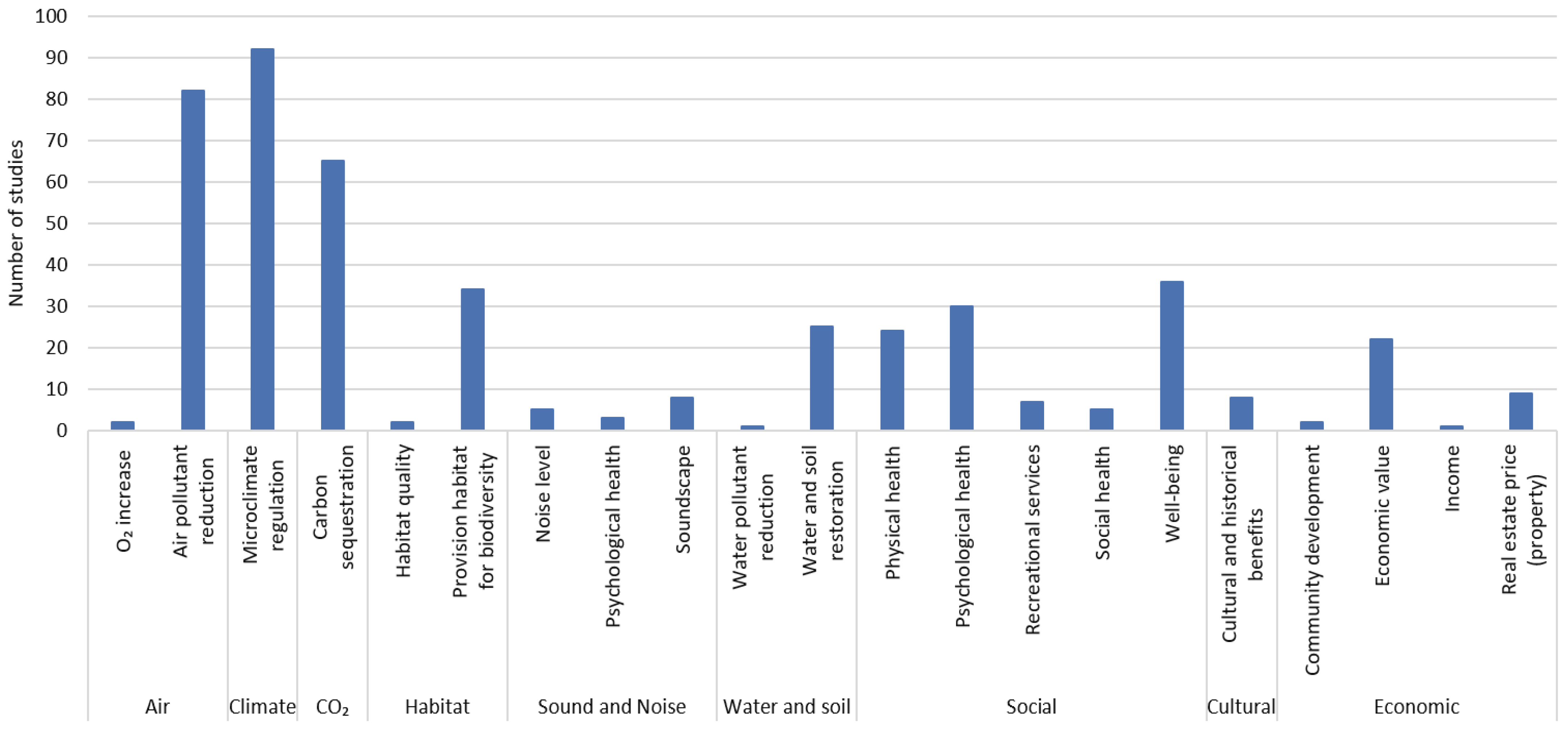

3.1. Distribution of the Measured Effects of Urban Forests

3.2. Methods and Metrics of Urban Forest Effects

3.3. Indicators Based on Ecosystem Service Cascade Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Imbalance Among Studies on Urban Forest Effects

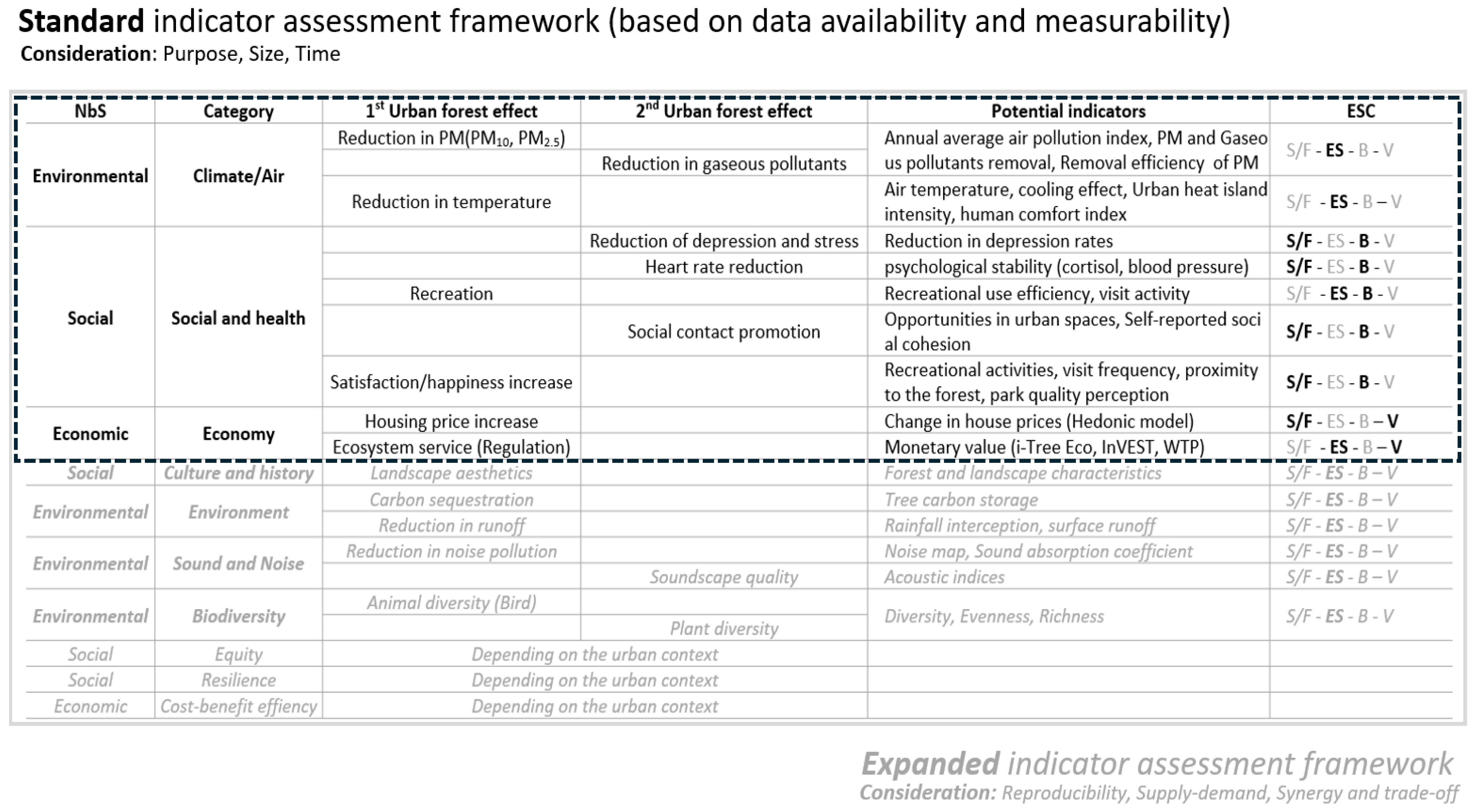

4.2. Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects

4.2.1. NbS Assessment Framework

4.2.2. Data Availability and Measurability for Practical Indicators

4.2.3. Spatiotemporal Scale and Geographical Characteristics

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Brien, L.E.; Urbanek, R.E.; Gregory, J.D. Ecological Functions and Human Benefits of Urban Forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 75, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Dwyer, J.F. Understanding the Benefits and Costs of Urban Forest Ecosystems. In Urban and Community Forestry in the Northeast; Kuser, J.E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-1-4020-4289-8. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, D.; Larondelle, N.; Andersson, E.; Artmann, M.; Borgström, S.; Breuste, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Gren, Å.; Hamstead, Z.; Hansen, R.; et al. A Quantitative Review of Urban Ecosystem Service Assessments: Concepts, Models, and Implementation. Ambio 2014, 43, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endreny, T.A. Strategically Growing the Urban Forest Will Improve Our World. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijnendijk, C.C.; Ricard, R.M.; Kenney, A.; Randrup, T.B. Defining Urban Forestry—A Comparative Perspective of North America and Europe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.G.E.; Devisscher, T. Strong Relationships between Urbanization, Landscape Structure, and Ecosystem Service Multifunctionality in Urban Forest Fragments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleyar, M.D.; Greve, A.I.; Withey, J.C.; Bjorn, A.M. An Integrated Approach to Evaluating Urban Forest Functionality. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. Assessing Nature’s Contributions to People. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Giannico, V.; Jim, C.Y.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Urban Forests, Ecosystem Services, Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions: Nexus or Evolving Metaphors? Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 37, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannico, V.; Spano, G.; Elia, M.; D’Este, M.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Green Spaces, Quality of Life, and Citizen Perception in European Cities. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban Greening to Cool Towns and Cities: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air Pollution Removal by Urban Forests in Canada and Its Effect on Air Quality and Human Health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; García, J. A New Evaluation Framework for Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) Projects Based on the Application of Performance Questions and Indicators Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Collier, M. Identifying Principles for the Design of Robust Impact Evaluation Frameworks for Nature-Based Solutions in Cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Andrade, A.; Dalton, J.; Dudley, N.; Jones, M.; Kumar, C.; Maginnis, S.; Maynard, S.; Nelson, C.R.; Renaud, F.G.; et al. Core Principles for Successfully Implementing and Upscaling Nature-Based Solutions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 98, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Urban Areas: Perspectives on Indicators, Knowledge Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities for Action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.; van der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.; Kronenberg, J.; de Groot, R. Benefits of Restoring Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S.J.; McPherson, E.G.; Calfapietra, C. The Urban Forest and Ecosystem Services: Impacts on Urban Water, Heat, and Pollution Cycles at the Tree, Street, and City Scale. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.R.; Geneletti, D.; Calfapietra, C. A Framework for Assessing and Implementing the Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Barrera, F.; Reyes-Paecke, S.; Banzhaf, E. Indicators for Green Spaces in Contrasting Urban Settings. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 62, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Pauleit, S.; Seeland, K.; de Vries, S. Benefits and Uses of Urban Forests and Trees. In Urban Forests and Trees: A Reference Book; Konijnendijk, C., Nilsson, K., Randrup, T., Schipperijn, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 81–114. ISBN 978-3-540-27684-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, M.; Fletcher, D.; Hagen-Zanker, A.; Jia, H.; Jones, L.; Li, H.; Loiselle, S.; Miller, J.; Reis, S.; Seifert-Dähnn, I.; et al. Why Scale Is Vital to Plan Optimal Nature-Based Solutions for Resilient Cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenkit, S.; Piyathamrongchai, K. A Review of Urban Green Spaces Multifunctionality Assessment: A Way Forward for a Standardized Assessment and Comparability. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson-Sköld, Y.; Klingberg, J.; Gunnarsson, B.; Cullinane, K.; Gustafsson, I.; Hedblom, M.; Knez, I.; Lindberg, F.; Ode Sang, Å.; Pleijel, H.; et al. A Framework for Assessing Urban Greenery’s Effects and Valuing Its Ecosystem Services. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 205, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbs, C.; Escobedo, F.J.; Zipperer, W.C. A Framework for Developing Urban Forest Ecosystem Services and Goods Indicators. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 99, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; da Cunha Pinto, J.P.; de Castro Medeiros, L.C. Countering the Effects of Urban Green Gentrification through Nature-Based Solutions: A Scoping Review. Nat.-Based Solut. 2024, 5, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening Cities—To Be Socially Inclusive? About the Alleged Paradox of Society and Ecology in Cities. Habitat. Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, S.; Moretti, M.; Amorim, J.H.; Branquinho, C.; Fares, S.; Morelli, F.; Niinemets, Ü.; Paoletti, E.; Pinho, P.; Sgrigna, G.; et al. Towards an Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Environmental Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Forest. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Assessment and Valuation of the Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Forests. In Ecology, Planning, and Management of Urban Forests: International Perspectives; Carreiro, M.M., Song, Y.-C., Wu, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 53–83. ISBN 978-0-387-71425-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pukowiec-Kurda, K. The Urban Ecosystem Services Index as a New Indicator for Sustainable Urban Planning and Human Well-Being in Cities. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, R.; Jacobs, S.; Leone, M.; Palliwoda, J.; Pinto, L.; Misiune, I.; Priess, J.A.; Pereira, P.; Wanner, S.; Ferreira, C.S.; et al. Keep It Real: Selecting Realistic Sets of Urban Green Space Indicators. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 095001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges. IUCN Gland. Switz. 2016, 97, 2036. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Davies, C.; Veal, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F. Review on the Application of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Forest Planning and Sustainable Management. Forests 2024, 15, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Hauer, R.J. Review on Urban Forests and Trees as Nature-Based Solutions over 5 Years. Forests 2021, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Carreiro, M.M.; Cherrier, J.; Grulke, N.E.; Jennings, V.; Pincetl, S.; Pouyat, R.V.; Whitlow, T.H.; Zipperer, W.C. Coupling Biogeochemical Cycles in Urban Environments: Ecosystem Services, Green Solutions, and Misconceptions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kwan, M.-P.; Wong, M.S.; Yu, C. Current Methods for Evaluating People’s Exposure to Green Space: A Scoping Review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 338, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Brillinger, M.; Guerrero, P.; Gottwald, S.; Henze, J.; Schmidt, S.; Ott, E.; Schröter, B. Planning Nature-Based Solutions: Principles, Steps, and Insights. Ambio 2021, 50, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Greener, Healthier, More Resilient Neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 Rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, L.; Giacco, G.; Moraca, M.; Pettenati, G.; Dansero, E.; Larcher, F. Spatializing Urban Forests as Nature-Based Solutions: A Methodological Proposal. Cities 2024, 144, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Byrne, J.; Pickering, C. A Systematic Quantitative Review of Urban Tree Benefits, Costs, and Assessment Methods across Cities in Different Climatic Zones. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundara Rajoo, K.; Karam, D.S.; Abdu, A.; Rosli, Z.; James Gerusu, G. Urban Forest Research in Malaysia: A Systematic Review. Forests 2021, 12, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potschin, M.B.; Haines-Young, R.H. Ecosystem Services: Exploring a Geographical Perspective. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2011, 35, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in Integrating the Concept of Ecosystem Services and Values in Landscape Planning, Management and Decision Making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.-J.; Su, C.-H.; Wei, Y.-P.; Willett, I.R.; Lü, Y.-H.; Liu, G.-H. Double Counting in Ecosystem Services Valuation: Causes and Countermeasures. Ecol. Res. 2011, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z. Ecosystem Service Cascade: Concept, Review, Application and Prospect. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Kumar, P.; Jones, L. Evaluating the Benefits of Urban Green Infrastructure: Methods, Indicators, and Gaps: Heliyon. Available online: https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(24)14477-5?uuid=uuid%3A6c523c92-e2b2-4f29-86b6-f6bbcaf5a259 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Vigevani, I.; Corsini, D.; Comin, S.; Fini, A.; Ferrini, F. Methods to Quantify Particle Air Pollution Removal by Urban Vegetation: A Review. Atmos. Environ. X 2024, 21, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. Cooling Benefits of Urban Tree Canopy: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, M.; Pintar, M.; Železnikar, Š.; Cvejić, R. Stakeholders’ Perceptions on the Role of Urban Green Infrastructure in Providing Ecosystem Services for Human Well-Being. Land 2022, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, R.; Gou, Z. Correlation between Vegetation Landscape and Subjective Human Perception: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Mihalko, C. A User-Feedback Indicator Framework to Understand Cultural Ecosystem Services of Urban Green Space. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvey, A.A. Promoting and Preserving Biodiversity in the Urban Forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewane, E.B.; Bajaj, S.; Velasquez-Camacho, L.; Srinivasan, S.; Maeng, J.; Singla, A.; Luber, A.; de-Miguel, S.; Richardson, G.; Broadbent, E.N.; et al. Influence of Urban Forests on Residential Property Values: A Systematic Review of Remote Sensing-Based Studies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilon, C.H.; Aronson, M.F.J.; Cilliers, S.S.; Dobbs, C.; Frazee, L.J.; Goddard, M.A.; O’Neill, K.M.; Roberts, D.; Stander, E.K.; Werner, P.; et al. Planning for the Future of Urban Biodiversity: A Global Review of City-Scale Initiatives. BioScience 2017, 67, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Moretti, M.; Bugalho, M.N.; Davies, Z.G.; Haase, D.; Hack, J.; Hof, A.; Melero, Y.; Pett, T.J.; Knapp, S. Understanding Biodiversity-Ecosystem Service Relationships in Urban Areas: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Chen, J.; van den Bosch, C.K.; Randrup, T.B. Nature-Based Solutions for Resilient Landscapes and Cities. Environ. Res. 2018, 165, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.; Kabisch, N.; de Bel, M.; Enzi, V.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Geneletti, G.; Lovinger, L.; Cardinaletti, M.; et al. An Impact Evaluation Framework to Support Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions Projects. Report Prepared by the EKLIPSE Expert Working Group on Nature-Based Solutions to Promote Climate Resilience in Urban Areas; Centre for Ecology and Hydrology: Wallingford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-906698-62-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, R.; Olafsson, A.S.; van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Rall, E.; Pauleit, S. Planning Multifunctional Green Infrastructure for Compact Cities: What Is the State of Practice? Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Zulian, G.; Maes, J.; Borg, M. Assessing Urban Ecosystem Services to Prioritise Nature-Based Solutions in a High-Density Urban Area. Nat.-Based Solut. 2021, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, A.; Palomo, I.; Codemo, A.; Rodeghiero, M.; Dubo, T.; Vallet, A.; Lavorel, S. Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions Exceed the Costs of Implementation. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2025, 2, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remme, R.P.; Meacham, M.; Pellowe, K.E.; Andersson, E.; Guerry, A.D.; Janke, B.; Liu, L.; Lonsdorf, E.; Li, M.; Mao, Y.; et al. Aligning Nature-Based Solutions with Ecosystem Services in the Urban Century. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 66, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.P.M.; Rodrigues, A.F.; Latawiec, A.E.; Dib, V.; Gomes, F.D.; Maioli, V.; Pena, I.; Tubenchlak, F.; Rebelo, A.J.; Esler, K.J.; et al. Framework for Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions for Water in Peri-Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, S.; Sheppard, S.R.J.; Condon, P.M. Urban Forest Indicators for Planning and Designing Future Forests. Forests 2016, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segnestam, L. Indicators of Environment and Sustainable Development Theories and Practical Experience; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Guenther, A.; Faiola, C. Effects of Anthropogenic and Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds on Los Angeles Air Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12191–12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category/Effect/Sub-Effect | Frequency | Category/Effect/Sub-Effect | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 84 | Social | 102 |

| O2 increase | 2 | Physical health | 24 |

| Oxygen production | 2 | Behavior change | 1 |

| Air pollutant reduction | 82 | Healthcare utilization | 3 |

| Reduction in air pollution | 3 | Physical activity promotion | 3 |

| Reduction in air pollution (haze) | 1 | Blood pressure reduction | 1 |

| Reduction in air pollution (smog) | 1 | Heart rate reduction | 14 |

| Reduction in gaseous pollutants | 26 | Mortality reduction | 2 |

| Reduction in PM | 48 | Psychological health | 30 |

| Reduction in SO42− | 1 | Mental health improvement | 2 |

| Reduction in toxic elements | 2 | Psychological restoration | 7 |

| Climate | 92 | Anxiety reduction | 1 |

| Microclimate regulation | 92 | Depression alleviation | 8 |

| Increase in relative humidity | 7 | Mental disorder reduction | 2 |

| Increase in winter temperature | 1 | Stress alleviation | 9 |

| Reduction in temperature | 82 | Sleep quality improvement | 1 |

| Reduction in wind speed | 2 | Recreational services | 7 |

| CO2 | 65 | Recreation increase | 7 |

| Carbon sequestration | 65 | Social health | 5 |

| Carbon sequestration | 65 | Learning improvement | 1 |

| Habitat | 36 | Social contact promotion | 4 |

| Habitat quality | 2 | Well-being | 36 |

| Habitat quality | 2 | Attention dynamics | 1 |

| Provision habitat for biodiversity | 34 | Comfort improvement | 2 |

| Animal diversity | 1 | Exercise satisfaction increase | 3 |

| Animal diversity (Arthropod) | 4 | Greater happiness | 9 |

| Animal diversity (Bird) | 13 | Satisfaction increase | 20 |

| Animal diversity (Mammal) | 3 | Safety perception improvement | 1 |

| Habitat quality | 3 | Cultural | 8 |

| Plant diversity | 9 | Cultural and historical benefits | 8 |

| Endangered species population sustainment | 1 | Landscape esthetics | 7 |

| Sound and Noise | 16 | Recreation and tourism | 1 |

| Noise level | 5 | Economic | 34 |

| Reduction in noise pollution | 5 | Community development | 2 |

| Psychological health | 3 | Community income | 1 |

| Psychological restoration | 1 | Job opportunities | 1 |

| Depression alleviation | 1 | Economic value | 22 |

| Stress alleviation | 1 | Ecosystem service (Culture) | |

| Soundscape | 8 | Ecosystem service (Regulation) | 16 |

| Increased satisfaction | 3 | Income | 1 |

| Soundscape quality | 5 | Monthly income | 1 |

| Water and soil | 26 | Real estate price (property) | 9 |

| Water pollutant reduction | 1 | Housing price increase | 8 |

| Reduction in total nitrogen and phosphorus | 1 | Land price increase | 1 |

| Water and soil restoration | 25 | Total | 463 |

| Evapotranspiration | 3 | ||

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) concentration | 1 | ||

| Rainfall erosivity | 1 | ||

| Rainfall interception | 1 | ||

| Reduction in runoff | 18 | ||

| Soil erosion mitigation | 1 |

| Effect | Methods * | Analysis Techniques | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | |||

| O2 increase | |||

| Oxygen production | Field measurement (2/5) | i-Tree Eco (urban forest effects model, UFORE) | Oxygen production |

| Reduction in air pollutants | |||

| Reduction in gaseous pollutants | Modeling/computer simulations (14/38), field measurement (12/38), open data usage (6/38) | i-Tree Eco (UFORE), i-Tree Canopy, structure from motion (SfM), unmanned aerial systems (UAS), WRF-Chem | Air quality, air pollutant removal efficiency |

| Reduction in PM (PM10, PM2.5) | Field measurement (19/72), modeling/computer simulations (18/72), field sampling and laboratory analysis (12/72), open data usage (9/72) | Eddy covariance tower, EddyPro software, ENVI-met, internet of things (IoT) technology, remote sensing imagery (Landsat, MODIS, Google satellite), Minitab 17, National stations and modeling (AERMOD), Wind tunnels, i-Tree Eco (UFORE), SfM, UAS | PM concentration, PM removal (efficiency) air quality |

| Climate | |||

| Microclimate regulation | |||

| Reduction in temperature | Field measurement (41/132), open data usage (30/132), spatial analysis (29/132), modeling/computer simulations (25/132) | Fixed/mobile measurements, GIS, (Geographically weighted regression (GWR)), ENVI-met, satellite images analysis (ECOSTRESS, LST, MODIS, landsat, sentinel, NDVI), unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), WRF-Chem, local data assimilation and prediction system (LDAPS) | LST intensity of urban heat island, cooling effect, air temperature reduction, shade effect |

| CO2 | |||

| Carbon sequestration | |||

| Carbon sequestration | Modeling/computer simulations (34/110) Field measurement (31/110) Open data usage (20/110) | i-Tree Eco, i-tree canopy, eddy covariance method, Plot-level carbon density models, life cycle assessment (LCA), regression analysis, integrated valuation of ecosystem services and trade-offs (InVEST), land change modeler (LCM), gis (Kriging interpolation) | Carbon sequestration/storage/stocks CO2 concentration/removal/uptake amount |

| Habitat Provision habitat for biodiversity | |||

| Animal diversity (Bird) | Field observation (8/21), open data usage (5/21) | Diversity, evenness, richness, structural equation modeling (SEM) | Species richness/abundance, species community composition |

| Sound and Noise Noise level | |||

| Reduction in noise pollution | Field measurement (4/8) | Measurement of microphone impedance tubes | Average noise reduction rate, noise intensity |

| Soundscape | |||

| Soundscape quality | Field measurement (5/7) | Raven sound analysis program, sound pressure level (SPL), soundscape (pleasantness, eventfulness) | Acoustic index, sound attribute |

| Water and soil Restoration of water and soil | |||

| Reduction in runoff | Modeling/computer simulations (11/28), field measurement (6/28) | Urban forest effects—hydrology model (UFORE-Hydro), i-Tree Eco (UFORE), IoT technology, LiDAR | Avoided runoff, rainfall interception |

| Social | |||

| Physical health | |||

| Heart rate reduction | Experiment (11/16) | Ovako Working Posture Assessment System (OWAS), Standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) | Blood pressure, heart rate |

| Psychological health | |||

| Depression alleviation | Experiment (8/12), survey/interviews (4/12) | Human emotions, Profile of Mood States (POMS) | Depression, anxiety, and sleep quality scores, rehabilitation from exhaustion disorder |

| Stress alleviation | Survey/interviews (7/13), experiment (6/13) | POMS, positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS), restorative outcome scale (ROS), subjective vitality scale (SVS) | Stress level, restoration and mood after nature experience |

| Recreational services | |||

| Recreation increase | Survey/interviews (3/9) | Questionnaire survey, SEM | Ecological and esthetic benefits, satisfaction |

| Social health | |||

| Social contact promotion | Survey/interviews (4/6) | Post-intervention surveys, face-to-face surveys, general health questionnaire | Social cohesion Social connection |

| Well-being | |||

| Greater happiness | Experiment (4/14), open data usage (3/14), survey/interviews (3/14) | Questionnaire survey, measurement of emotional states of forest visitors, facial expression analysis | Facial expressions scores Emotional perception Degree of satisfaction Happiness level Positive emotion index (PEI) Computer vision (Street view images) |

| Satisfaction increase | Survey/interviews (17/27) experiment (4/27), text analysis (2/27) | Questionnaire survey, high-frequency words analysis, social media data (text) | Life satisfaction, visitors’ perceptions of experience/park activities and recreational use, facial expression scores |

| Cultural Cultural and historical benefits | |||

| Landscape esthetics | Survey/interviews (4/10), spatial analysis (2/10), experiment (2/10) | Questionnaire survey, semantic differential method | Visual quality, cultural ecosystem services |

| Economic Real estate price (property) | |||

| Housing price increase | Open data usage (6/16), modeling/computer simulations (5/16) | Hedonic pricing model, SEM, willingness to pay | Housing prices, willingness to pay |

| Economic value of ecosystem service | |||

| Ecosystem service (Regulation) | Modeling/computer simulations (12/24) open data usage (8/24) | InVEST, i-Tree Eco, EPA Ben MAP model, return on investment | Ecological benefits ecosystem service values return on investment Social cost |

| Effect | Functional/Structural Indicators | → | Ecosystem Service Indicators | → | Human Benefit Indicators | → | Value Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | |||||||

| O2 increase | Production of O2 | ||||||

| Reduction in air pollutants | Normalized pigment chlorophyll ratio index (NPCI), species, diameter at breast height (DBH), leaf area index (LAI), landscape index | Dry deposition flux of PM, PM concentrations, Reduction in air pollutants | Respiratory mortality, green exposure | Monetary value of doctor visit | |||

| Climate | |||||||

| Microclimate regulation | NDVI, landscape index, green space area and ratio, tree canopy, green vegetation index | Change in temperature (ΔT), LST, Temperature reduction, cooling supply index, cooling capacity value, cooling efficiency (CE), cooling distance | Thermal comfort index, thermal stress index, physiologically equivalent temperature (PET) | ||||

| CO2 | |||||||

| Carbon sequestration | Carbon sequestration and storage amount | ||||||

| Habitat | |||||||

| Habitat quality | Green space range | ||||||

| Provision habitat for biodiversity | Green space area and canopy cover | Diversity and abundance index, species composition, forest functional diversity index | Perceived restorative properties and self-reported benefits | ||||

| Sound and Noise | |||||||

| Noise level | Noise exposure (noise map) | Self-reported perception of noise exposure | |||||

| Soundscape | Soundscape diversity index, acoustic indicators | Characteristics of public recreational behavior | |||||

| Water and soil | |||||||

| Restoration of water and soil | Landscape index | Reduction in runoff, indicator of run-off retention service, soil ecosystem service (e.g., nutrient retention and release, water storage) | |||||

| Social | |||||||

| Physical health | NDVI, quality of green space, green space exposure, nature Contact within UGS, Natural outdoor environments, canopy cover, green view index (GVI), visible green index (VGI), floor GVI, visits to green space, number of trees and tree traits, health-oriented index system (availability, accessibility, features), 3–30–300 green space indicators, park vitality | Physiological index, doctor visit | Sales of medication | ||||

| Psychological health | Mental health indicators (stress, general health), physiological indicators (heart rate), self-reported mental health | ||||||

| Recreational services | Recreational use efficiency, visit activity, spatial perception satisfaction preference, | ||||||

| Social health | Opportunities in urban spaces, self-reported social cohesion | ||||||

| Well-being | Positive emotional index (PEI), sentiment level, resilience assessment, community life satisfaction | ||||||

| Cultural | |||||||

| Cultural and historical benefits | GVI, landscape index, function of UGS, green canopy, VGI | Cultural landscape service, cultural ecosystem service indicator (sense of place, recreation, psychological value, esthetic value, social value) | Perceived sensory dimensions (PSD), perception level | ||||

| Economic | |||||||

| Economic value | Ecological ecosystem services | Replacement value, monetary value | |||||

| Real estate price (property) | Green space area and accessibility | Change in home price |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, J.; Joo, H.-R.; Sou, H.-D.; Choi, S.; Park, C.-R. Development of an Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects Through a Scoping Review. Forests 2025, 16, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121870

Jeong J, Joo H-R, Sou H-D, Choi S, Park C-R. Development of an Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects Through a Scoping Review. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121870

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Jinsuk, Hye-Rin Joo, Hong-Duck Sou, Sumin Choi, and Chan-Ryul Park. 2025. "Development of an Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects Through a Scoping Review" Forests 16, no. 12: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121870

APA StyleJeong, J., Joo, H.-R., Sou, H.-D., Choi, S., & Park, C.-R. (2025). Development of an Indicator Assessment Framework for Urban Forest Effects Through a Scoping Review. Forests, 16(12), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121870