From Ecological Functions to Green Space Management: Driving Factors and Planning Implications of Urban Ecosystem Service Bundles

Abstract

1. Introduction

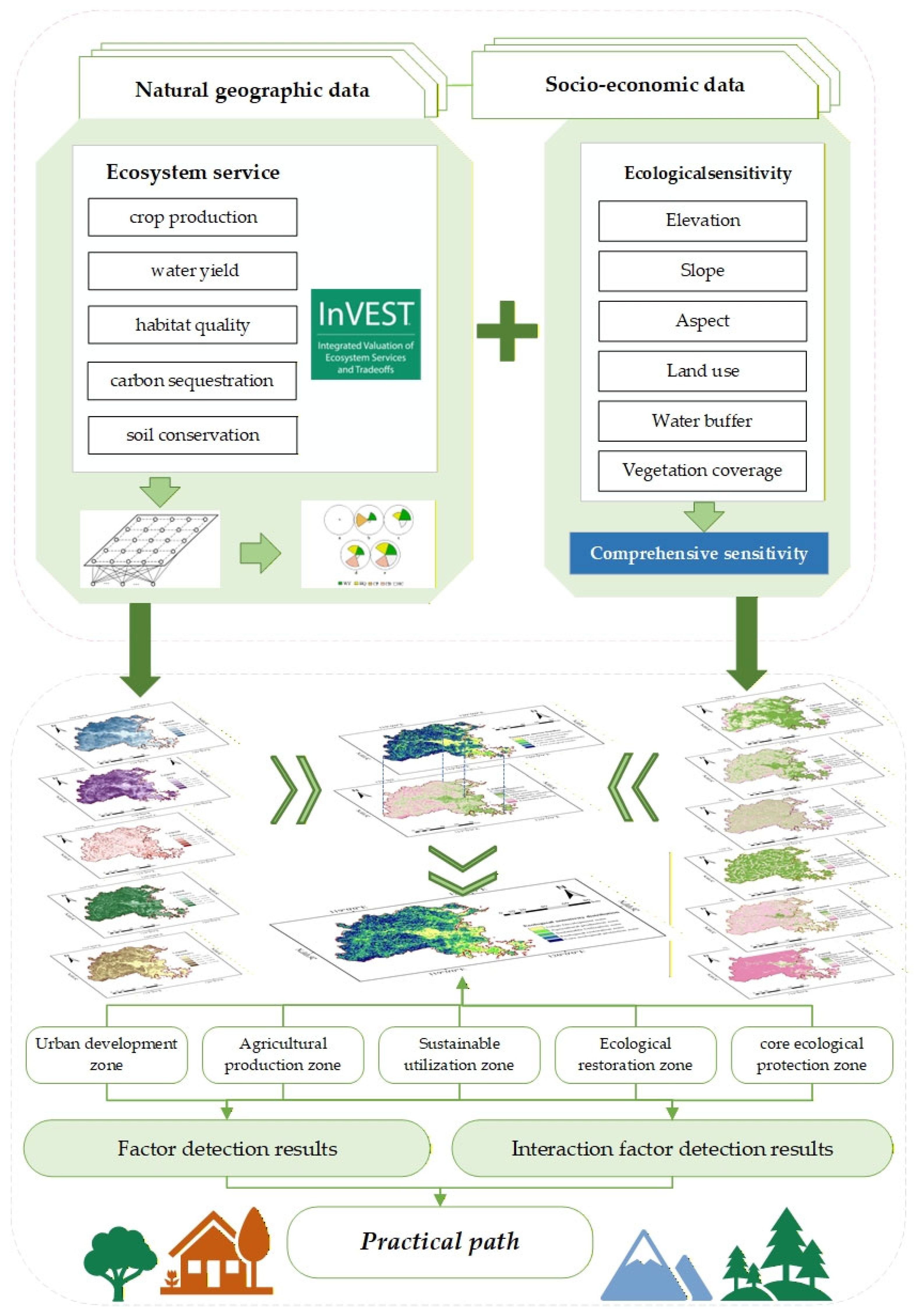

2. Materials and Methods

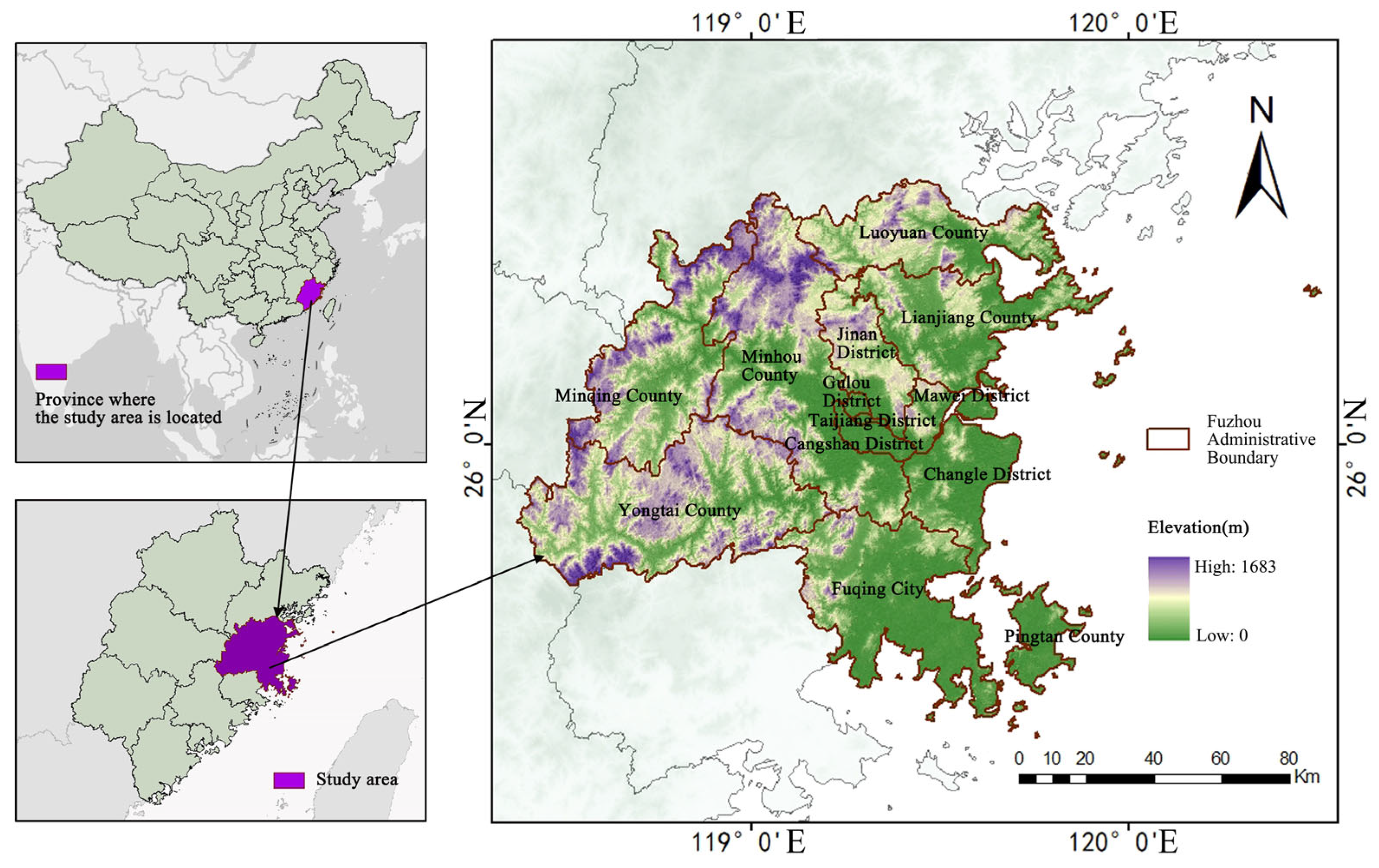

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

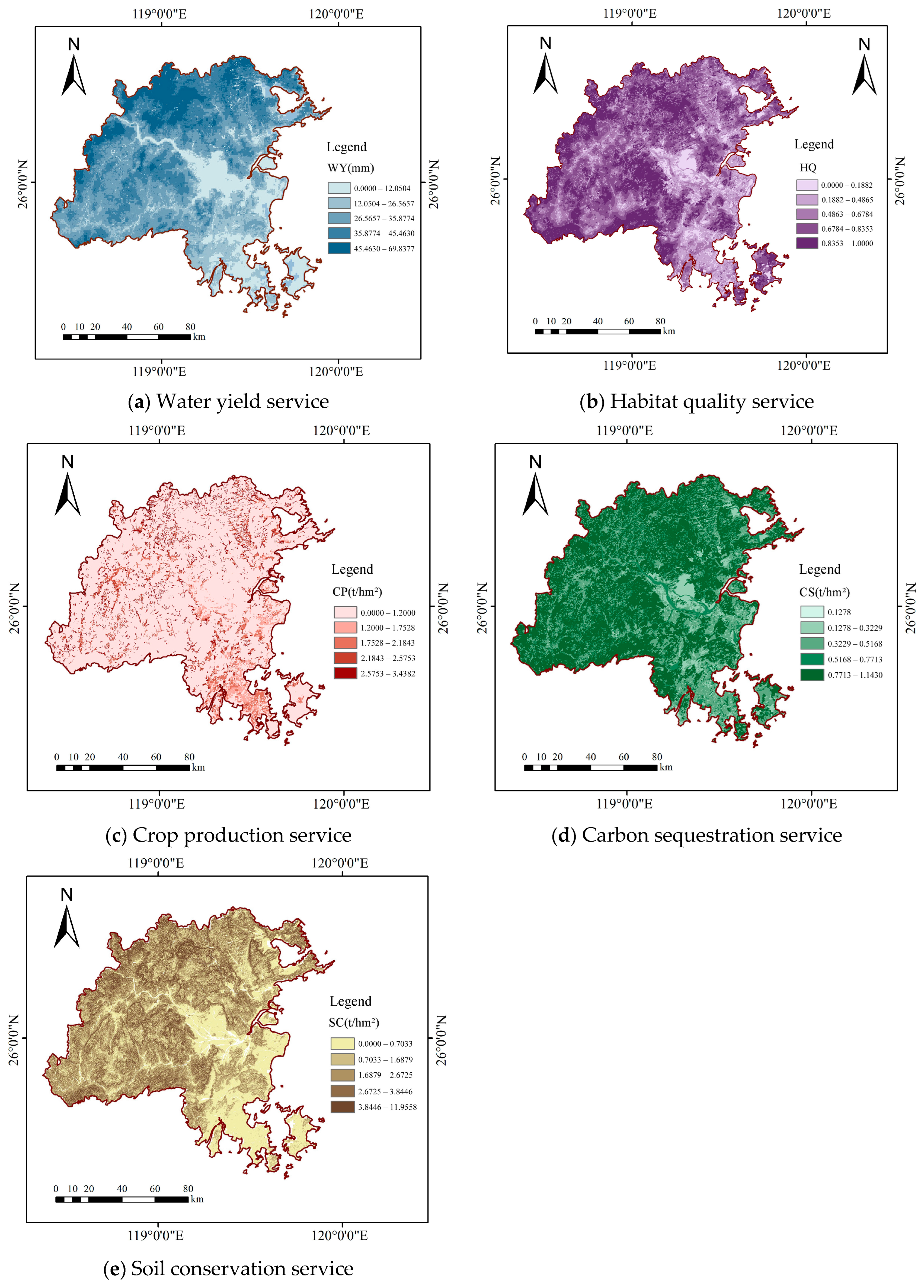

2.3. Quantitation of Ess

2.3.1. Crop Production (CP)

2.3.2. Water Yield (WY)

2.3.3. Habitat Quality (HQ)

2.3.4. Carbon Sequestration (CS)

2.3.5. Soil Conservation (SC)

2.3.6. Uncertainty Consideration

2.4. Ecosystem Service Bundles Identification

2.5. Ecological Function Partitioning

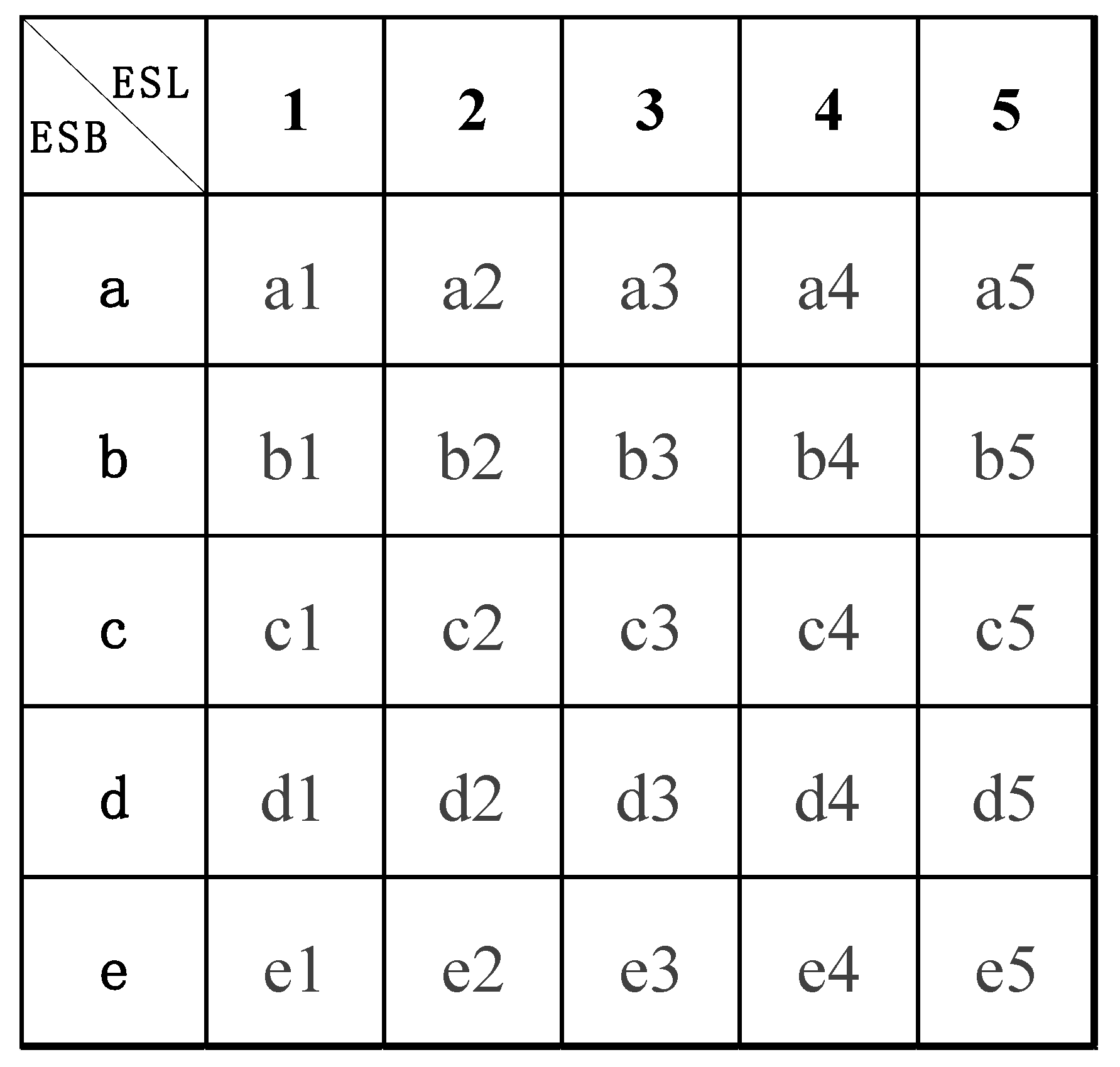

2.5.1. Ecological Sensitivity Evaluation Factors and Grading Standards

2.5.2. Ecological Function Partitioning Standards

- Core Ecological Protection Zone: Assigned to areas providing the most critical regulating services Bundles (d), (e), (c) exhibiting high habitat quality, carbon sequestration, and water yield) coupled with high to extreme ecological sensitivity (ESL ≥ 4). These areas are paramount for maintaining regional ecological security and require the strictest protection against development activities.

- Ecological Restoration Zone: Assigned to areas with important ecosystem services but showing signs of degradation risk or moderate sensitivity (typically ESL ≥ 3). This includes ESB types that are valuable but potentially fragile, necessitating restorative measures to enhance ecosystem stability and resilience.

- Sustainable Utilization Zone: Assigned to areas with relatively stable and moderate service bundles and lower sensitivity (ESL ≤ 2). These areas can support certain human activities but must be managed sustainably to prevent degradation, focusing on maintaining the existing service supply.

- Agricultural Production Zone: Dominated by the grain production bundle (b) and characterized by low sensitivity (ESL ≤ 2), this zone is prioritized for agricultural activities. Management should focus on optimizing production while minimizing ecological impacts through eco-agricultural practices.

- Urban Development Zone: Characterized by the low service potential bundle (a) and low sensitivity (ESL ≤ 2), this zone is deemed most suitable for accommodating urban expansion and socioeconomic activities. Ecological management here focuses on enhancing livability through greening and mitigating negative environmental impacts.

2.6. Driver Identification

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Ecosystem Services

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Ecosystem Service Bundles

3.3. Ecological Sensitivity Distribution

3.4. Ecological Functional Partitioning

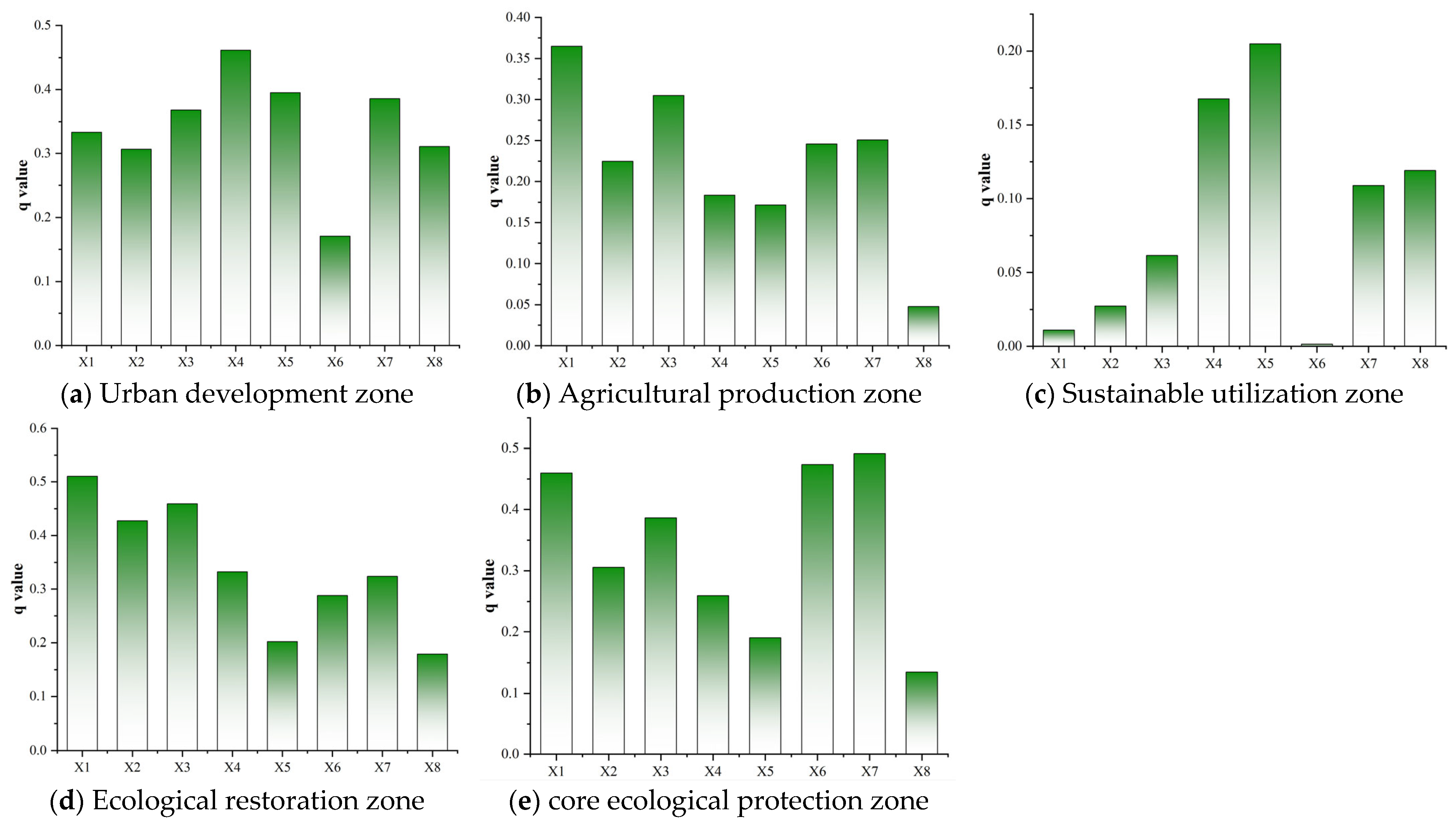

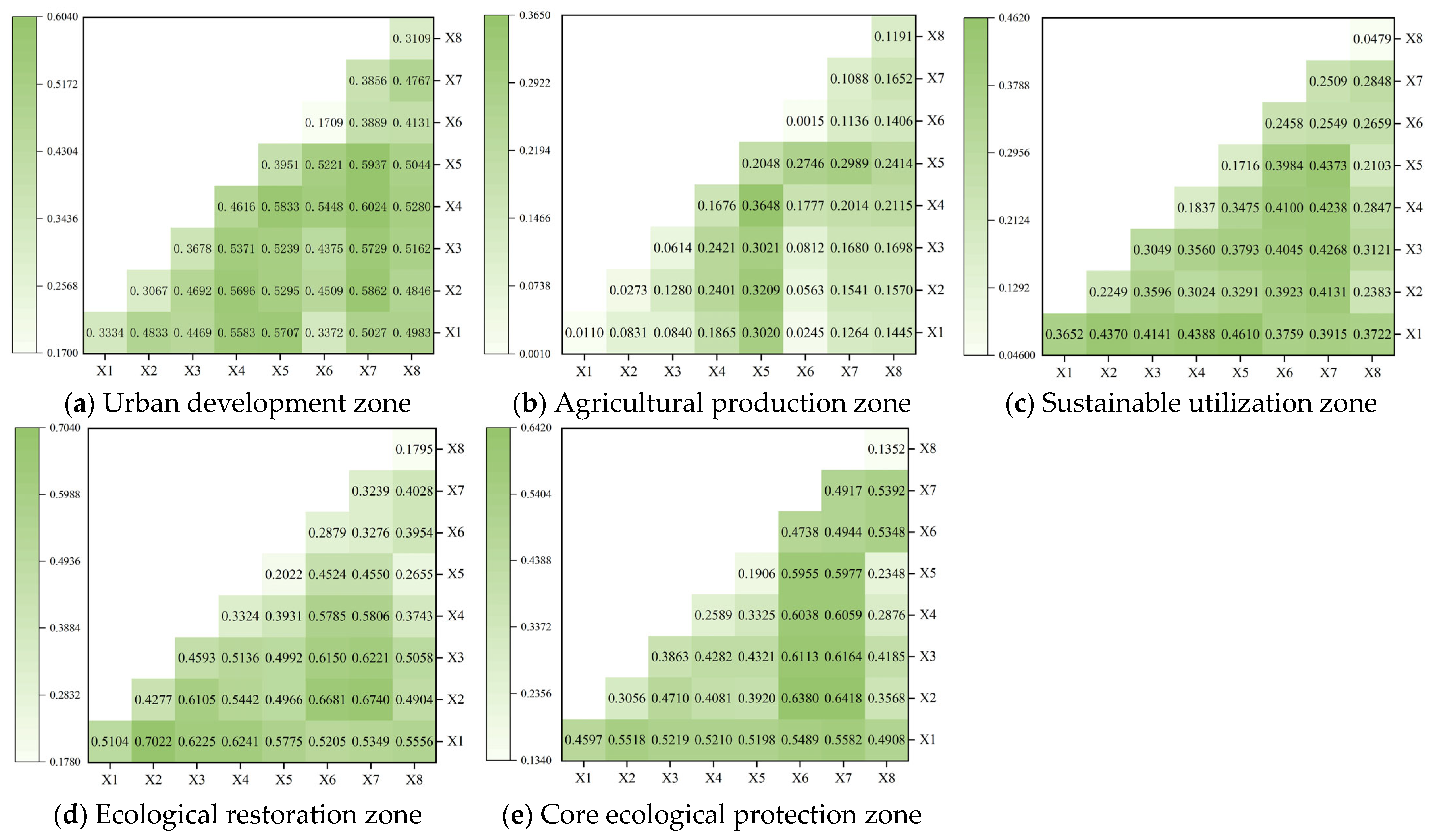

3.5. Identification of Ecological Functional Partition Driver Factors in Fuzhou City

4. Discussion

4.1. From Ecosystem Services to Ecological Functional Zoning

4.2. Unveiling the Driving Mechanisms: Nonlinear Interactions Between Natural and Socioeconomic Factors

4.3. Practical Path of Urban Green Space Management Based on Zoning Framework

4.4. Limitations and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, J. Urban Ecology and Sustainability: The State-of-the-Science and Future Directions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. Valuing Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services toward the Goals of Efficiency, Fairness, and Sustainability. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R. The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.Y.F. An Ecosystem-Based Analysis of Urban Sustainability by Integrating Ecosystem Service Bundles and Socio-Economic-Environmental Conditions in China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Xu, S.; He, X.; Yao, J. Analysis of Trade-Off and Synergy of Ecosystem Services and Driving Forces in Urban Agglomerations in Northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Liu, M. An Ecosystem Service Trade-Off Management Framework Based on Key Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J. Assessment of Supply–Demand Relationships Considering the Interregional Flow of Ecosystem Services. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 27710–27729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ying, L. Effects of Agricultural Land Consolidation on Ecosystem Services: Trade-Offs and Synergies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Fu, B. Landscape Functional Zoning at a County Level Based on Ecosystem Services Bundle: Methods Comparison and Management Indication. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 249, 109315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Peterson, G.D.; Bennett, E.M. Ecosystem Service Bundles for Analyzing Tradeoffs in Diverse Landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5242–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Larondelle, N.; Andersson, E.; Artmann, M.; Borgström, S.; Breuste, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E. A Quantitative Review of Urban Ecosystem Service Assessments: Concepts, Models, and Implementation. Ambio 2014, 43, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baró, F.; Palomo, I.; Zulian, G.; Vizcaino, P.; Haase, D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Mapping Ecosystem Service Capacity, Flow and Demand for Landscape and Urban Planning: A Case Study in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region. Land. Use Policy 2016, 57, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, J. Understanding the Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Social-Ecological Drivers of Ecosystem Service Supply-Demand Bundles in the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025; early access, advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, H.; Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qu, T.; et al. Construction and Optimization of Ecological Security Patterns in Dryland Watersheds Considering Ecosystem Services Flows. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, S.; Xia, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Exploring Watershed Ecological Risk Bundles Based on Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of Shanxi Province, China. Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 118040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Bao, G.; Xu, H. Spatial Variation in Ecosystem Service Relationships in Alpine Ecosystems: A Case Study of the Daxing’anling Forest Area, Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Hao, R.; Li, J.; Qiao, J. Identifying Ecosystem States with Patterns of Ecosystem Service Bundles. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.J.; Tang, H.P.; Xu, Y. Integrating Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being into Management Practices: Insights from a Mountain-Basin Area, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27 Pt A, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusens, J.; Barraclough, A.D.; Maren, I.E. Integration Matters: Combining Socio-Cultural and Biophysical Methods for Mapping Ecosystem Service Bundles. Ambio 2023, 52, 1004–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, G.; Tian, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, Y. Linking Ecosystem Services Trade-Offs, Bundles and Hotspot Identification with Cropland Management in the Coastal Hangzhou Bay Area of China. Land. Use Policy 2020, 97, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, M.; Drzejewski, W.O.; Borowik, T.; Drzejewska, B.; Nowak, S.; Ajek, R.W. Analyses of Least Cost Paths for Determining Effects of Habitat Types on Landscape Permeability: Wolves in Poland. Acta Theriol. 2011, 56, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, L.; Greene, S.; Scholefield, P.; Dunbar, M. The Importance of Scale in the Development of Ecosystem Service Indicators? Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Yuan, S.; Prishchepov, A.V. Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity of Ecosystem Service Interactions and Their Social-Ecological Drivers: Implications for Spatial Planning and Management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 189, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Yang, W.U.; Zhang, L.U.; Hull, V.; Wang, Z. Strengthening Protected Areas for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Yu, X.C.; Li, T.Y.; Chen, Z. The Construction of an Ecological Security Pattern Based on the Comprehensive Evaluation of the Importance of Ecosystem Service and Ecological Sensitivity: A Case of Yangxin County, Hubei Province. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1154166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Z. Identification of Harbin Ecological Function Degradation Areas Based on Ecological Importance Assessment and Ecological Sensitivity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, Q.; Dong, J.; Piao, L.; Cui, Z. Ecological Importance Evaluation and Ecological Function Zoning of Yanshan-Taihang Mountain Area of Hebei Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Li, T.; Wang, Q. Exploring the Ecosystem Services Bundles and Influencing Drivers at Different Scales in Southern Jiangxi, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.Y.; Sun, C.Z.; Hao, S. Spatial Heterogeneity and Driving Forces of Ecosystem Services: An Individual-Pair-Bundle Perspective. J. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 35, 2039–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Liu, X.T.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Z.H. Variations in Ecosystem Service Value and Its Driving Factors in the Nanjing Metropolitan Area of China. Forests 2023, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavitti, A.M.; Floris, A.; Serra, S. Urban Standards and Ecosystem Services: The Evolution of the Services Planning in Italy from Theory to Practice. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Fuzhou 2023 Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development. Fuzhou Municipal People’s Government Portal. Available online: https://tjj.fuzhou.gov.cn/zwgk/tjzl/ndbg/202404/t20240412_4807960.htm (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Tao, J.; Lu, Y.; Ge, D.; Dong, P.; Gong, X.; Ma, X. The Spatial Pattern of Agricultural Ecosystem Services from the Production-Living-Ecology Perspective: A Case Study of the Huaihai Economic Zone, China. Land. Use Policy 2022, 122, 106355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.; Tallis, H.T.; Ricketts, T.; Guerry, A.D.; Wood, S.A.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Nelson, E.; Ennaanay, D.; Wolny, S.; Olwero, N. InVEST User’s Guide; Natural Capital Project: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Fu, G.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Z. Spatial Heterogeneity of Ecosystem Service Bundles and the Driving Factors in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 479, 144006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nieto, A.P.; García-Llorente, M.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; Martín-López, B. Mapping Forest Ecosystem Services: From Providing Units to Beneficiaries. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 4, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motegi, R.; Seki, Y. SMLSOM: The Shrinking Maximum Likelihood Self-Organizing Map. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2023, 182, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Wang, C.M.; Lv, B.H. Comparative Analysis of Ecological Sensitivity Assessment Using the Coefficient of Variation Method and Machine Learning. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.D.; Zhang, X.G.; Nan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y. Ecological Sensitivity Assessment and Spatial Pattern Analysis of Land Resources in Tumen River Basin, China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F.C.; Zengin, M.; Tekin Cure, C. Determination of Ecologically Sensitive Areas in Denizli Province Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Ling, H.; Han, F.; Kong, Z.; Wang, W. Function Zoning Based on Spatial and Temporal Changes in Quantity and Quality of Ecosystem Services under Enhanced Management of Water Resources in Arid Basins. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.X.; Zuo, L.Y.; Gao, J.B. Exploring the Driving Factors of Trade-Offs and Synergies Among Ecological Functional Zones Based on Ecosystem Service Bundles. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jeppesen, E.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, C.; Sun, X. Assessment of the Effectiveness of China’s Protected Areas in Enhancing Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 65, 101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, M.P.; Villarino, S.; Levers, C.; Baumann, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Mastrangelo, M. Widespread and Major Losses in Multiple Ecosystem Services as a Result of Agricultural Expansion in the Argentine Chaco. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 2485–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Wang, S. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Services and Driving Factors in the Yellow River Basin of Henan Province, China. Forests 2024, 15, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, D. Detecting the Complex Relationships and Driving Mechanisms of Key Ecosystem Services in the Central Urban Area Chongqing Municipality, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hong, W.; Qiu, R.; Hong, T.; Chen, C.; Wu, C. Geographic Variations of Ecosystem Service Intensity in Fuzhou City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 512, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. Research Progress on Urban Forest Ecosystem Services and Multifunctionality. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11557–11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, K.; Xie, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Exploring Natural-Social Impacts on the Complex Interactions of Ecosystem Services in Ecosystem Service Bundles. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2024, 10, 0236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, X.; Gu, B.; Wang, K. Evaluation and Functional Zoning of the Ecological Environment in Urban Space—A Case Study of Taizhou, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Yang, Y. Identification of Ecological Improvement Zones in Different Ecological Functional Zones in Northwest Hubei, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 111032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huo, R.; Feng, Z. The Evaluation of Territorial Spatial Planning from the Perspective of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Meng, X.; Liu, B. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Factors of Ecosystem Services in the Upper Fenhe Watershed, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wei, S.; Wang, K.; Li, H. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Factors of Ecosystem Services Based on InVEST-OPGD Model: A Case Study in Kunming. Environ. Res. Commun. 2025, 7, 065029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhan, J.Y.; Zhao, F.; Yan, H.M.; Zhang, F.; Wei, X.Q. Impacts of Urbanization-Induced Land-Use Changes on Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of the Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, B. Evidence of Green Space Sparing to Ecosystem Service Improvement in Urban Regions: A Case Study of China’s Ecological Red Line Policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The Performance and Potential of Protected Areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Newton, A.C.; Diaz, A.; Bullock, J.M. Enhancement of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by Ecological Restoration: A Meta-Analysis. Science 2009, 325, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauman, K.A.; Daily, G.C.; Duarte, T.K.; Mooney, H.A. The Nature and Value of Ecosystem Services: An Overview Highlighting Hydrologic Services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Oddi, F.J.; Miguez, F.E.; Bartomeus, I.; Orr, M.C.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Kremen, C. Working Landscapes Need at Least 20% Native Habitat. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. Can the Ecological Protection Red Line Policy Promote Food Security?—Based on the Empirical Analysis of Land Protection in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1654217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, P.; Bai, X. Benefits and Co-Benefits of Urban Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Cities: Six Current and Emerging Themes. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1039–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Spatial Planning for Multifunctional Green Infrastructure: Growing Resilience in Detroit. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, J.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, T.; Cao, P. Defining Important Areas for Ecosystem Conservation in Qinghai Province under the Policy of Ecological Red Line. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural geographic data | DEM data | 30 m resolution DEM data | (http://www.gscloud.cn) (accessed on 15 March 2024) |

| soil data | These data were used to determine the soil parameters for the INVEST model, including soil depth and soil texture data | (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn) (accessed on 5 July 2024) | |

| precipitation and evaporation data | Extract raw data and calculate annual mean with a resolution of 1000 m for 2020 | (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn) (accessed on 14 July 2024) | |

| Plant Available Water Capacity | Used for INVEST model calculation with a resolution of 1000 m | (http://globalchange.bnu.edu.cn/research/cdtb.jsp) (accessed on 16 July 2024) | |

| Socio-economic data | Land use data | Land use type data for 2020 with a spatial resolution of 30 m | (http://www.resdc.cn) (accessed on 17 July 2024) |

| GDP | GDP data for 2020 | (www.fuzhou.gov.cn) (accessed on 18 July 2024) | |

| Urbanization | Urbanization rate data in 2020 | (www.fuzhou.gov.cn) | |

| Population density | Population density data for 2020 | (http://www.resdc.cn) (accessed on 20 July 2024) |

| Grading | Elevation | Slope | Slope | Water Buffer | Land Use Type | Vegetation Cover | Grading Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insensitive | <300 | <8 | South | <50 | Construction land | <0.2 | 1 |

| Mild sensitivity | 300~<600 | 8~<15 | Southeast, Southwest | 50~200 | Shrubs, grasslands | 0.2–0.4 | 2 |

| Moderately sensitive | 600~<900 | 15~<25 | The east, the west | 200~<500 | arable land | 0.4–0.6 | 3 |

| Highly sensitive | 900~<1200 | 25~<45 | Northeast, Northwest | 500~<800 | woodland | 0.6–0.8 | 4 |

| Extremely sensitive | ≥1200 | ≥45 | North | >800 | Waters, wetlands | >0.8 | 5 |

| Ecological Function Zone | Division Basis | Corresponding Encoding |

|---|---|---|

| Core ecological protection zone | ESL ≥ 4 + e/d/c bundle | e5, e4, d5, c5 |

| Ecological restoration zone | ESL ≥ 3 + Service function degradation area | e3, d4, c4, b5, b4, a5, a4, c4 |

| Sustainable Utilization zone | ESL ≤ 3 + Service function stability area | e2, e1, d3, d2, d1, c2, c3 |

| Agricultural production zone | ESL ≤ 2 + b bundle dominant | b1, b2, b3 |

| Urban Development zone | ESL ≤ 2 + a bundle dominant | a2, a1, c1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, N.; Rao, D.; Yao, X.; Zhu, Z. From Ecological Functions to Green Space Management: Driving Factors and Planning Implications of Urban Ecosystem Service Bundles. Forests 2025, 16, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121856

Wei J, Wu M, Liu N, Rao D, Yao X, Zhu Z. From Ecological Functions to Green Space Management: Driving Factors and Planning Implications of Urban Ecosystem Service Bundles. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121856

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Jingyi, Mengbo Wu, Na Liu, Daihui Rao, Xiong Yao, and Zhipeng Zhu. 2025. "From Ecological Functions to Green Space Management: Driving Factors and Planning Implications of Urban Ecosystem Service Bundles" Forests 16, no. 12: 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121856

APA StyleWei, J., Wu, M., Liu, N., Rao, D., Yao, X., & Zhu, Z. (2025). From Ecological Functions to Green Space Management: Driving Factors and Planning Implications of Urban Ecosystem Service Bundles. Forests, 16(12), 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121856