Extreme Climate Drivers and Their Interactions in Lightning-Ignited Fires: Insights from Machine Learning Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Lightning Fire Data

2.2.2. Extreme Climate Data

2.2.3. Meteorological, Vegetation, and Fire Weather Data

2.2.4. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Model Construction

2.3.1. Logistic Regression

2.3.2. Random Forest

2.3.3. XGBoost

2.3.4. Convolutional Neural Network

- (1)

- Input Layer: A 9 × 9 patch was used as the input window to capture local environmental context surrounding each sampled grid cell.

- (2)

- Feature Extraction: The feature extraction module consisted of two convolutional blocks. The first and second convolutional layers contained 32 and 64 filters, respectively, each with a kernel size of 3 × 3 and zero padding to preserve feature map dimensions. Each convolutional layer was followed by a 2 × 2 max-pooling layer to reduce feature dimensionality and a dropout rate of 0.25 to prevent overfitting. All convolutional layers used the ReLU activation function.

- (3)

- Classification Layer: The extracted spatial features were flattened and passed through two fully connected layers with 64 and 32 neurons, both using ReLU activation. The output layer consisted of a single neuron with a Sigmoid activation function, producing the predicted probability of lightning-ignited fire for each input patch.

- (4)

2.4. Model Performance Evaluation

2.5. Identification of Key Extreme Climate Factors

2.6. Interaction Among Extreme Climate Factors

3. Results

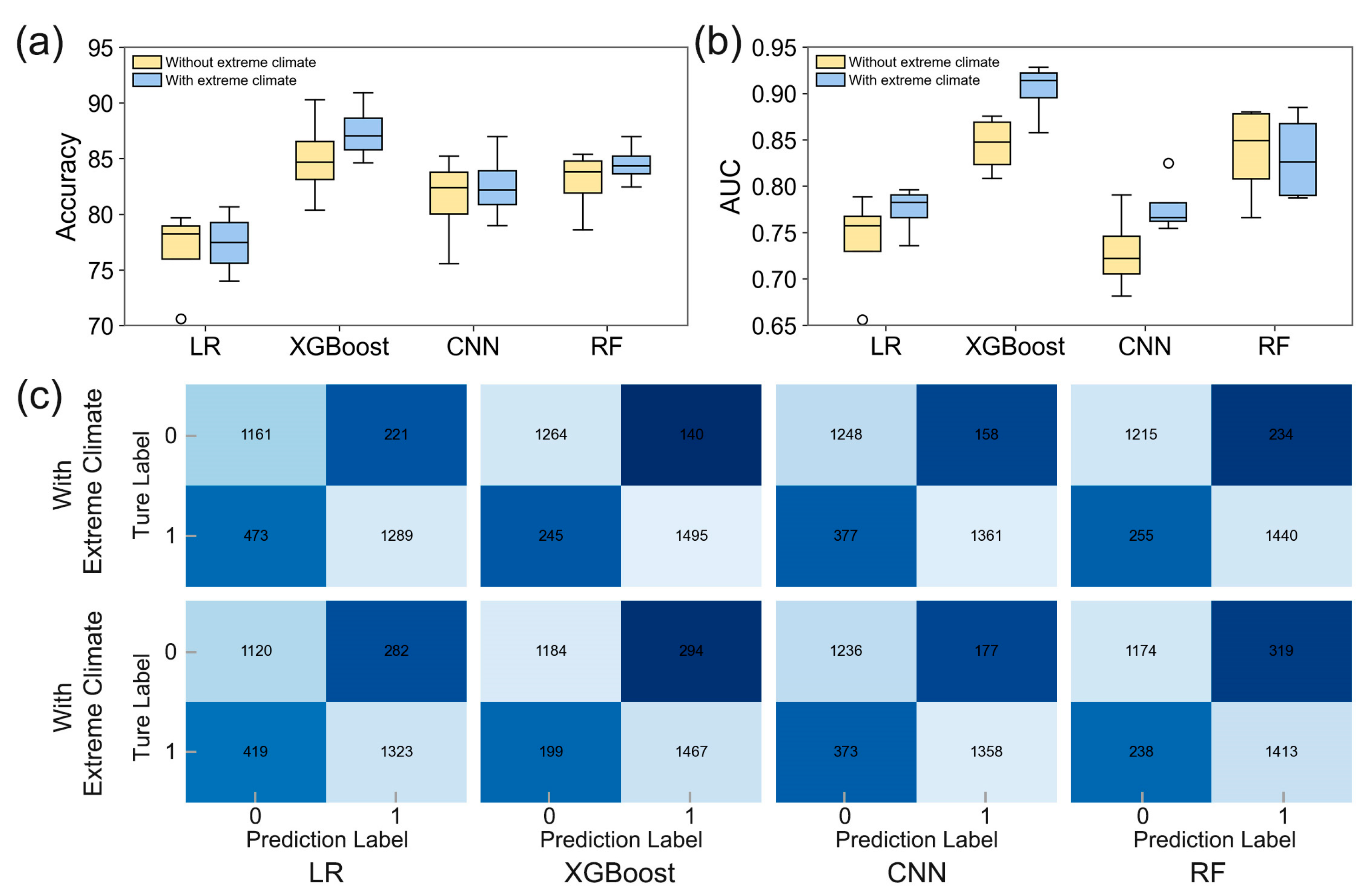

3.1. Model Performance

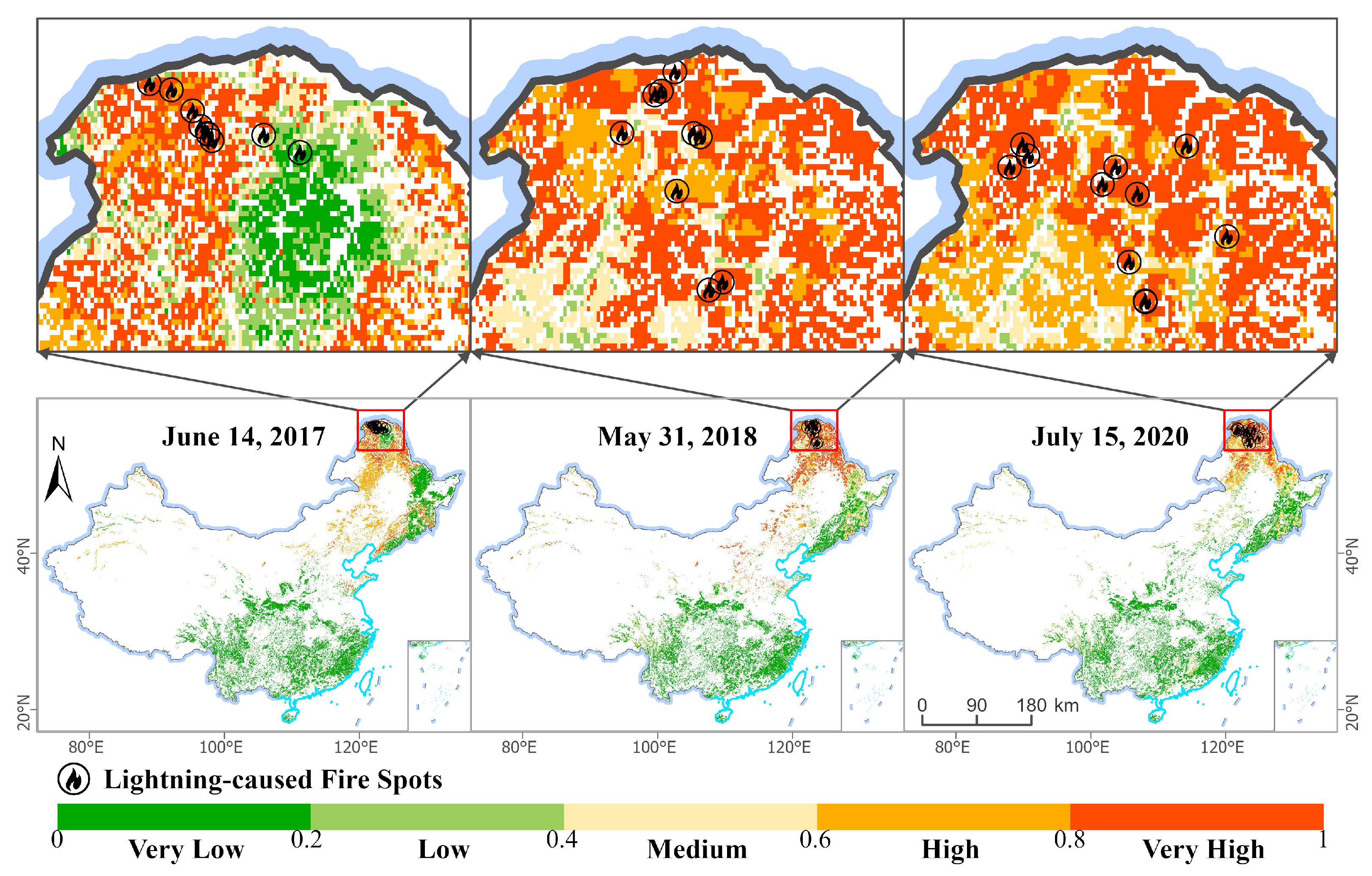

3.2. Validation of Lightning-Fire Prediction

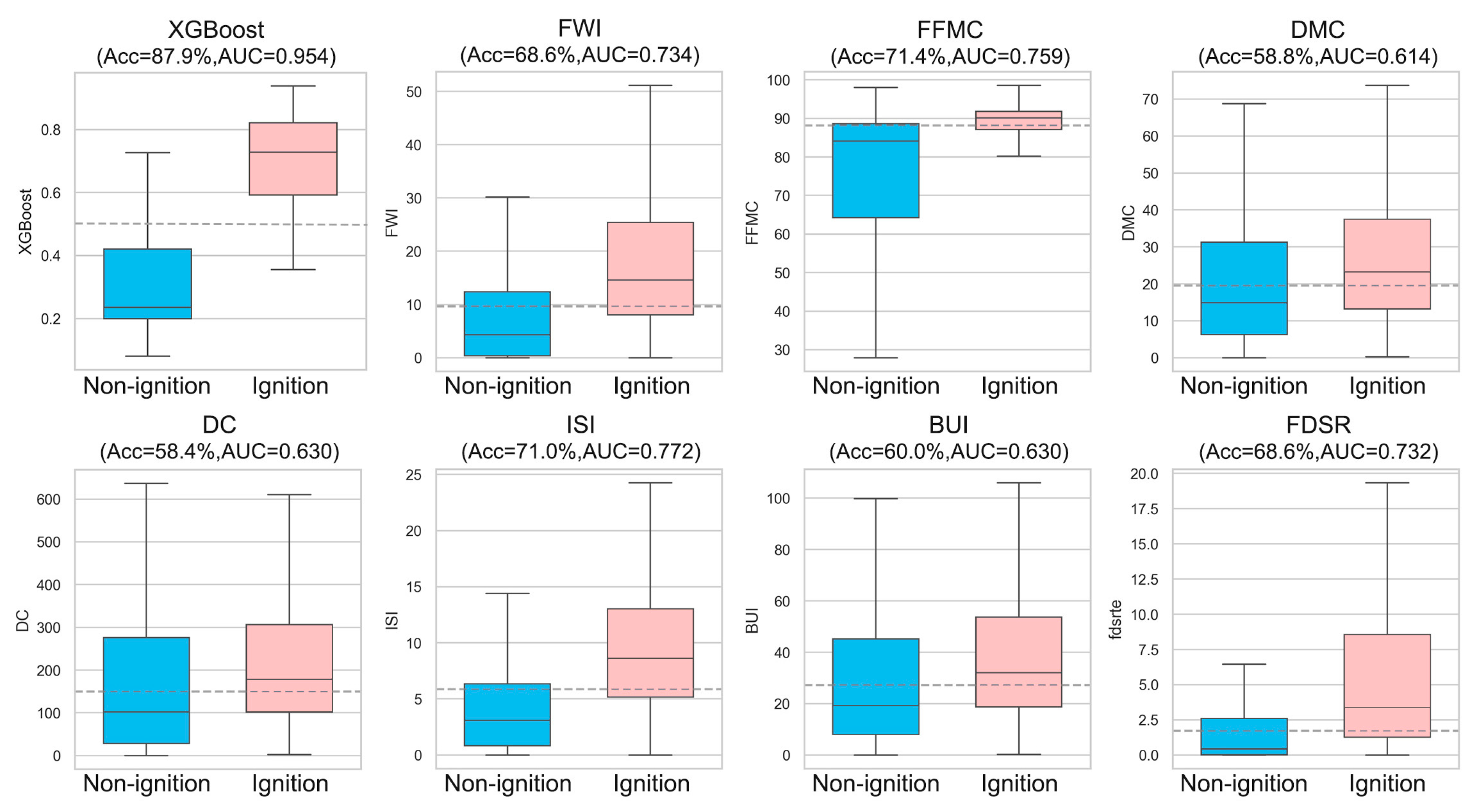

3.3. Identification of Key Extreme Climate Factors and Their Driving Effects

3.4. Interactions and Combined Effects of Extreme Climate Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Improvement of Lightning Fire Prediction Performance by Extreme Climate Factors

4.2. Effects of Key Extreme Climate Factors on Lightning Fire Ignition

4.3. Effects of Interactions Among Extreme Climate Factors on Lightning Fire Ignition

4.4. Limitations and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Invernón, F.J.; Gordillo-Vázquez, F.J.; Huntrieser, H.; Jöckel, P. Variation of Lightning-Ignited Wildfire Patterns under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntrieser, H.; Lichtenstern, M.; Scheibe, M.; Aufmhoff, H.; Schlager, H.; Pucik, T.; Minikin, A.; Weinzierl, B.; Heimerl, K.; Pollack, I.B.; et al. Injection of Lightning-Produced NOx, Water Vapor, Wildfire Emissions, and Stratospheric Air to the UT/LS as Observed from DC3 Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 6638–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.; Otto, F.; Stuart-Smith, R.; Harrington, L. Extreme Weather Impacts of Climate Change: An Attribution Perspective. Environ. Res. Clim. 2022, 1, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, N.J.; Henley, B.J.; Sen Gupta, A.; Lippmann, T.J.R.; Clarke, H.; Dowdy, A.J.; Sharples, J.J.; Nolan, R.H.; Zhang, T.; Wooster, M.J.; et al. Connections of Climate Change and Variability to Large and Extreme Forest Fires in Southeast Australia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.T.; Hanley, H.; Mahesh, A.; Reed, C.; Strenfel, S.J.; Davis, S.J.; Kochanski, A.K.; Clements, C.B. Climate Warming Increases Extreme Daily Wildfire Growth Risk in California. Nature 2023, 621, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Flannigan, M.D.; Guindon, L.; Swystun, T.; Castellanos-Acuna, D.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Canadian Forests Are More Conducive to High-Severity Fires in Recent Decades. Science 2025, 387, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, T.A.J.; Jones, M.W.; Finney, D.; van der Werf, G.R.; van Wees, D.; Xu, W.; Veraverbeke, S. Extratropical Forests Increasingly at Risk Due to Lightning Fires. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, S.C.P.; Cai, X.; Jain, P.; Flannigan, M.D. Seasonality and Trends in Human- and Lightning-Caused Wildfires ≥ 2 Ha in Canada, 1959–2018. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, B.; Bratoev, I.; Crowley, M.A.; Zhu, Y.; Senf, C. Distribution and Characteristics of Lightning-Ignited Wildfires in Boreal Forests—The BoLtFire Database. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 2249–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z. Effects of Forest Fire Prevention Policies on Probability and Drivers of Forest Fires in the Boreal Forests of China during Different Periods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Tian, X.; Liu, J. A Fire Regime Zoning System for China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 717499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Fang, K.; Yao, Q.; Zhou, F.; Ou, T.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Bai, M.; et al. Impacts of Changes in Climate Extremes on Wildfire Occurrences in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 157, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, J.K.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Joseph, M.B.; Koontz, M.J.; Mahood, A.L.; McGlinchy, J.; Cattau, M.E.; Williams, A.P. Warming Weakens the Night-Time Barrier to Global Fire. Nature 2022, 602, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Clarke, H.; Clarke, M.F.; McColl Gausden, S.C.; Nolan, R.H.; Penman, T.; Bradstock, R. Warmer and Drier Conditions Have Increased the Potential for Large and Severe Fire Seasons across South-Eastern Australia. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 1933–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Shi, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Shi, F.; Yang, J.; Bai, Y.; Liu, X. Lightning-Ignited Wildfire Prediction in the Boreal Forest of Northeast China. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 253, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Tian, Y.; Quan, Y.; Liu, J. Simulation of Forest Fire Spread Based on Artificial Intelligence. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Oppong, F. Lightning-Induced Wildfires: An Overview. Fire 2024, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhou, B.; Duan, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Climate Extremes Become Increasingly Fierce in China. Innovation 2023, 4, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artés Vivancos, T. Global Wildfire Database for GWIS (2021). Available online: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.943975 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Shmuel, A.; Lazebnik, T.; Glickman, O.; Heifetz, E.; Price, C. Global Lightning-Ignited Wildfires Prediction and Climate Change Projections Based on Explainable Machine Learning Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.K. Assessing the Predictive Capability of Ensemble Tree Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using XGBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine, and Random Forest. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Pan, X.; Tansey, K.; Abdulla, A.; Guluzade, R.; Yang, Z.; He, M.; Zhu, C.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y. Wildfire Probability Assessment and Analysis Based on Multi-Source Data in Guangxi Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Odom, W.E.; Shobe, C.M.; Doctor, D.H.; Bester, M.S.; Ore, T. Exploring the Influence of Input Feature Space on CNN-Based Geomorphic Feature Extraction From Digital Terrain Data. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2023EA002845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kang, W.; Jung, Y. Application of the Class-Balancing Strategies with Bootstrapping for Fitting Logistic Regression Models for Post-Fire Tree Mortality in South Korea. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2023, 30, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, M.; Santos, S.; Vieira, A.; Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Alvelos, F. Estimating Wildfire Ignition Probabilities with Geographic Weighted Logistic Regression. J. Appl. Stat. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, F. A Forest Fire Susceptibility Modeling Approach Based on Integration Machine Learning Algorithm. Forests 2023, 14, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lin, H.; Hu, H. Forest-Fire-Risk Prediction Based on Random Forest and Backpropagation Neural Network of Heihe Area in Heilongjiang Province, China. Forests 2023, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, A.C.; De Carli, M.M.; Shtein, A.; Dorman, M.; Lyapustin, A.; Kloog, I. Correcting Measurement Error in Satellite Aerosol Optical Depth with Machine Learning for Modeling PM2.5 in the Northeastern USA. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, Y.; Helman, D.; Glickman, O.; Gabay, D.; Brenner, S.; Lensky, I.M. Forecasting Fire Risk with Machine Learning and Dynamic Information Derived from Satellite Vegetation Index Time-Series. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojić, A.; Stanić, N.; Vuković, G.; Stanišić, S.; Perišić, M.; Šoštarić, A.; Lazić, L. Explainable Extreme Gradient Boosting Tree-Based Prediction of Toluene, Ethylbenzene and Xylene Wet Deposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaturu, A.; Vadrevu, K.P. Evaluation of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Fire Prediction in Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Han, B.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, W.; Yang, Z. Machine Learning Methods in Weather and Climate Applications: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; He, Z.; Wang, Z. Monthly Climate Prediction Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Long Short-Term Memory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, F. The Value of Probabilistic Prediction for Lightning Ignited Fires. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL099669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, F.; Liu, F. SHAP-Powered Insights into Short-Term Drought Dynamics Disturbed by Diurnal Temperature Range across China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 316, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Extracting Spatial Effects from Machine Learning Model Using Local Interpretation Method: An Example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Abu Salem, F.K.; Hayes, M.J.; Smith, K.H.; Tadesse, T.; Wardlow, B.D. Explainable Machine Learning for the Prediction and Assessment of Complex Drought Impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ling, Z.; Liu, L.; Sun, S. Revealing the Driving Factors of Urban Wetland Park Cooling Effects Using Random Forest Regression and SHAP Algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessilt, T.D.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Chen, Y.; Randerson, J.T.; Scholten, R.C.; van der Werf, G.; Veraverbeke, S. Future Increases in Lightning Ignition Efficiency and Wildfire Occurrence Expected from Drier Fuels in Boreal Forest Ecosystems of Western North America. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvar, Z.; Saeidi, S.; Mirkarimi, S. Integrating Meteorological and Geospatial Data for Forest Fire Risk Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Williams, A.P.; Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Yebra, M.; Bryant, C.; Konings, A.G. Dry Live Fuels Increase the Likelihood of Lightning-Caused Fires. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, S.; Liu, D.; Piao, S. Susceptibility of Vegetation Low-Growth to Climate Extremes on Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 331, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Z. Rapid Rises in the Magnitude and Risk of Extreme Regional Heat Wave Events in China. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 34, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhai, P. More Frequent and Widespread Persistent Compound Drought and Heat Event Observed in China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Ayala, J.J.; Mann, J.; Grosvenor, E. Antecedent Rainfall, Excessive Vegetation Growth and Its Relation to Wildfire Burned Areas in California. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotjahn, R. Weather Extremes That Affect Various Agricultural Commodities. In Extreme Events and Climate Change: A Multidisciplinary Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Tougeron, K.; Gols, R.; Heinen, R.; Abarca, M.; Abram, P.K.; Basset, Y.; Berg, M.; Boggs, C.; Brodeur, J.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Climate Change and Insects. Ecol. Monogr. 2023, 93, e1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Zuleta, K.; Pausas, J.G.; Paula, S. FLAMITS: A Global Database of Plant Flammability Traits. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2024, 33, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Magalhães, R.Q.; Schwilk, D.W. Moisture Absorption and Drying Alter Nonadditive Litter Flammability in a Mixed Conifer Forest. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depicker, A.; De Baets, B.; Baetens, J.M. Wildfire Ignition Probability in Belgium. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wei, C. Evaluation of Microwave Soil Moisture Data for Monitoring Live Fuel Moisture Content (LFMC) over the Coterminous United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.M.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Jain, P.; Flannigan, M.D.; Williamson, G.J. Global Increase in Wildfire Risk Due to Climate-driven Declines in Fuel Moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 1544–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, K.; Graham, L.J.; Flannigan, M.; Belcher, C.M.; Kettridge, N. Landscape Controls on Fuel Moisture Variability in Fire-Prone Heathland and Peatland Landscapes. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoteeshkumar Reddy, P.; Sharples, J.J.; Lewis, S.C.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E. Modulating Influence of Drought on the Synergy between Heatwaves and Dead Fine Fuel Moisture Content of Bushfire Fuels in the Southeast Australian Region. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2021, 31, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.; Black, A.S.; Irving, D.; Matear, R.J.; Monselesan, D.P.; Risbey, J.S.; Squire, D.T.; Tozer, C.R. Global Increase in Wildfire Potential from Compound Fire Weather and Drought. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Schwartz, M.W.; Thorne, J.H. Intensified Burn Severity in California’s Northern Coastal Mountains by Drier Climatic Condition. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, W.; Fu, J.; Wei, H. On the Extreme Precipitation Events With and Without Lightning over Eastern and Southern China. JGR Atmos. 2025, 130, e2025JD043509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikov, D.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Loikith, P.C.; Nauslar, N.J.; Bekris, Y.; Singh, D. Lightning-Ignited Wildfires in the Western United States: Ignition Precipitation and Associated Environmental Conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Q. Extreme Climate Drivers and Their Interactions in Lightning-Ignited Fires: Insights from Machine Learning Models. Forests 2025, 16, 1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121861

Wang Y, Wu Y, Cui H, Liu Y, Li M, Yang X, Zhao J, Yu Q. Extreme Climate Drivers and Their Interactions in Lightning-Ignited Fires: Insights from Machine Learning Models. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121861

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu, Yingda Wu, Huanjia Cui, Yilin Liu, Maolin Li, Xinyu Yang, Jikai Zhao, and Qiang Yu. 2025. "Extreme Climate Drivers and Their Interactions in Lightning-Ignited Fires: Insights from Machine Learning Models" Forests 16, no. 12: 1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121861

APA StyleWang, Y., Wu, Y., Cui, H., Liu, Y., Li, M., Yang, X., Zhao, J., & Yu, Q. (2025). Extreme Climate Drivers and Their Interactions in Lightning-Ignited Fires: Insights from Machine Learning Models. Forests, 16(12), 1861. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121861