Evaluating the Carbon Budget and Seeking Alternatives to Improve Carbon Absorption Capacity at Pinus rigida Plantations in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Ecological Background of P. rigida

2.3. Measurement of Stand Density and Analysis of Population Structure

2.4. Measurement of Net Primary Productivity (NPP)

2.5. Measurement of Soil Respiration

2.6. Calculation of Carbon Absorption Capacity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Diameter Class Distribution of Tree Species

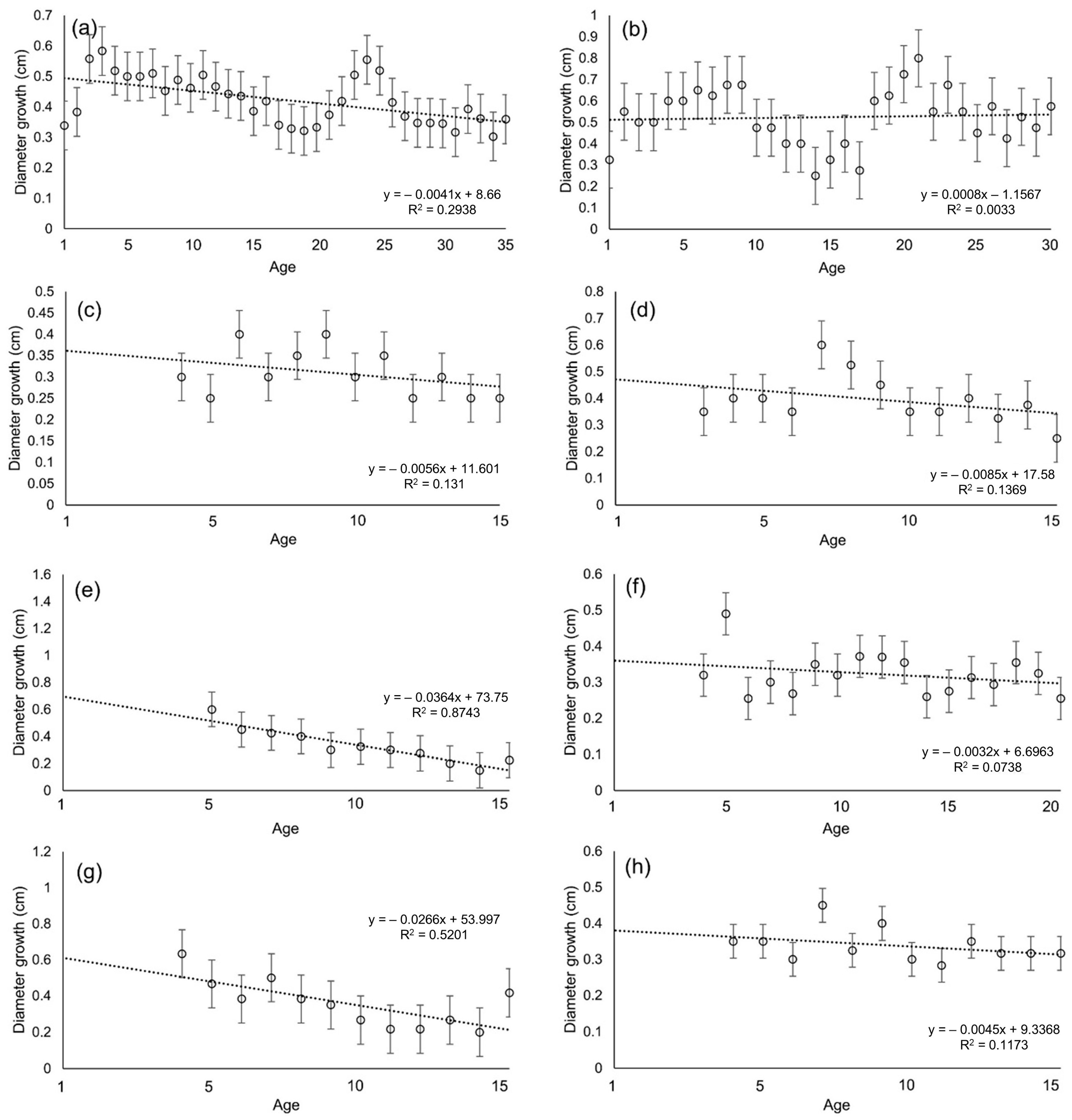

3.2. Diameter Growth

3.3. NPP of Individual Trees

3.4. NPP of P. rigida Stand

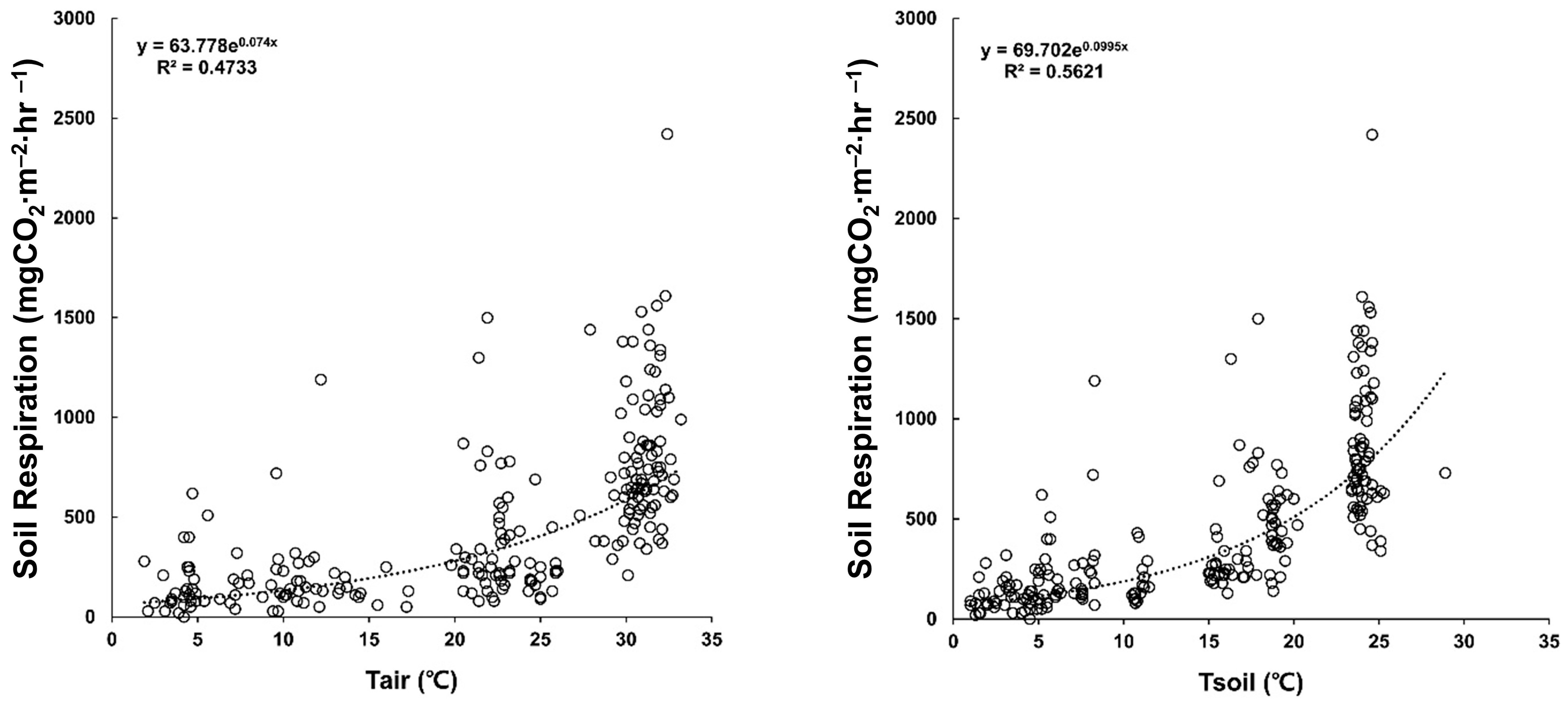

3.5. Seasonal Changes in Soil Respiration and Amount of Annual Soil Respiration

3.6. NEP of P. rigida Community

4. Discussion

4.1. Successional Dynamics in P. rigida Plantations

4.2. Changes in NPP with the Stand Age

4.3. Ecological Challenge to Achieve Carbon Neutrality

4.4. Measures to Enhance Carbon Absorption Capacity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geng, Q.; Arif, M.; Yin, F.; Chen, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; He, X.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J. Characteristics of Forest Understory Herbaceous Vegetation and Its Influencing Factors in Biodiversity Hotspots in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, Q.; Lei, T.; Cui, G. Coniferous and Broad-Leaved Mixed Forest Has the Optimal Forest Therapy Environment among Stand Types in Xinjiang. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Park, B.B. Comparison of Allometric Equation and Destructive Measurement of Carbon Storage of Naturally Regenerated Understory in a Pinus Rigida Plantation in South Korea. Forests 2020, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Tiwari, A.; Anjum, J.; Sharma, S. Dynamics of Carbon Storage and Status of Standing Vegetation in Temperate Coniferous Forest Ecosystem of North Western Himalaya India. Vegetos 2021, 34, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Forestry for a Low Carbon Future: Integrating Forests and Wood Products in Climate Change Strategies; FAO Forestry Paper. No. 177; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, D. Forests and Climate Change; United Nations Forum on Forests: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- KFS. Development of Greenhouse Gas Inventory System in forest sector of for Post-2012 Climate Regime; National Institute of Forest Science: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013.

- Gucker, C.L. Pinus rigida; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory: Missoula, MT, USA, 2007.

- Lee, H.; An, J.H.; Shin, H.C.; Lee, C.S. Assessment of Restoration Effects and Invasive Potential Based on Vegetation Dynamics of Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida Mill.) Plantation in Korea. Forests 2020, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, W.T.; Knoepp, J.D.; Vose, J.M.; Laseter, S.N.; Webster, J.R. Response and Recovery of Water Yield and Timing, Stream Sediment, Abiotic Parameters, and Stream Chemistry Following Logging. In Long-Term Response of a Forest Watershed Ecosystem: Clearcutting in the Southern Appalachians; Swank, W.T., Webster, J.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 36–56. ISBN 978-0-19-537015-7. [Google Scholar]

- Anyomi, K.A.; Neary, B.; Chen, J.; Mayor, S.J. A Critical Review of Successional Dynamics in Boreal Forests of North America. Environ. Rev. 2022, 30, 563–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Fang, S.; Fang, X.; Jin, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Lin, F.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Nie, Y.; Ouyang, S. Forest Understory Vegetation Study: Current Status and Future Trends. For. Res. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, C.; Ji, L.; Zuo, Z.; Beckline, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, X. Development of Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation, Its Problems and Future Solutions: A Review. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Phillips, R.P.; Rillig, M.C.; Angst, G.; Kiers, E.T.; Bonfante, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Liu, Z. Mycorrhizal Allies: Synergizing Forest Carbon and Multifunctional Restoration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Barclay, H.; Roitberg, B.; Lalonde, R. Forest Productivity Enhancement and Compensatory Growth: A Review and Synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 575211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desport, L. Implementation of Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage in Global Socio-Techno-Economic Models: Long-Term Optimization of the Energy System and Industry Decarbonization. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, N. Timber Production and Carbon Emission Reductions through Improved Forest Management and Substitution of Fossil Fuels with Wood Biomass. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Búrquez, A.; Chidumayo, E.; Colgan, M.S.; Delitti, W.B.; Duque, A.; Eid, T.; Fearnside, P.M.; Goodman, R.C. Improved Allometric Models to Estimate the Aboveground Biomass of Tropical Trees. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 3177–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Khan, W.R.; Ali, A.; Nazre, M. Assessment of Above-Ground Biomass in Pakistan Forest Ecosystem’s Carbon Pool: A Review. Forests 2021, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, F.S. The Ecological Significance of the Herbaceous Layer in Temperate Forest Ecosystems. BioScience 2007, 57, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, J.; Kangas, A.; Maltamo, M.; Kukkonen, M.; Packalen, P. Assessing Biodiversity Using Forest Structure Indicators Based on Airborne Laser Scanning Data. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 546, 121376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Davies, S.J.; Bennett, A.C.; Gonzalez-Akre, E.B.; Muller-Landau, H.C.; Joseph Wright, S.; Abu Salim, K.; Almeyda Zambrano, A.M.; Alonso, A.; Baltzer, J.L.; et al. CTFS-ForestGEO: A Worldwide Network Monitoring Forests in an Era of Global Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, P.; Lau, A.; Disney, M.; Calders, K.; Burt, A.; Gonzalez de Tanago, J.; Bartholomeus, H.; Brede, B.; Herold, M. Data Acquisition Considerations for Terrestrial Laser Scanning of Forest Plots. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 196, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Robinson, G.R.; Robinson, I.P.; Lee, H. Regeneration of Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida) Stands Inhibited by Fire Suppression in Albany Pine Bush Preserve, New York. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H.; An, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, C.S. Allogenic Succession of Korean Fir (Abies koreana Wils.) Forests in Different Climate Condition. Ecol. Res. 2018, 33, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Kim, R.; Lee, K.; Pyo, J.; Kim, S.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.; Park, H. Carbon Emission Factors and Biomass Allometric Equations by Species in Korea; Korea Forest Research Institute Report; National Institute of Forest Science: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2014; pp. 14–18.

- Kim, S.C. Effect of Vegetation on the Soil Erosion After Forest Fire, Korea. Master’s Thesis, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-S.; Choung, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-C.; Shin, S.-S.; Noh, C.-H.; Park, S.-D. Development of Vegetation Structure after Forest Fire in the East Coastal Region, Korea. Korean J. Ecol. 2004, 27, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raich, J.W.; Tufekciogul, A. Vegetation and Soil Respiration: Correlations and Controls. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S. Method for Assessing Forest Carbon Sinks by Ecological Process-Based Approach-a Case Study for Takayama Station, Japan. Korean J. Ecol. 2003, 26, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Zenner, E.K. Toward Managing Mixed-Species Stands: From Parametrization to Prescription. For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRue, E.A.; Knott, J.A.; Domke, G.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Guo, Q.; Hisano, M.; Oswalt, C.; Oswalt, S.; Kong, N.; Potter, K.M.; et al. Structural Diversity as a Reliable and Novel Predictor for Ecosystem Productivity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2023, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Will, R.E.; Zhang, B. Structural Diversity Is Better Associated with Forest Productivity than Species or Functional Diversity. Ecology 2024, 105, e4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Zhang, N.; Bongers, F.J.; Staab, M.; Schuldt, A.; Fornoff, F.; Lin, H.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Hipp, A.L.; Li, S. Tree Species and Genetic Diversity Increase Productivity via Functional Diversity and Trophic Feedbacks. eLife 2022, 11, e78703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Schmid, B.; Xu, W.; Bongers, F.J.; Chen, G.; Tang, T.; Wang, Z.; Svenning, J.; Ma, K.; Liu, X. The Functional Diversity–Productivity Relationship of Woody Plants Is Climatically Sensitive. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Reich, P.B.; Taylor, A.R.; An, Z.; Chang, S.X. Resource Availability Enhances Positive Tree Functional Diversity Effects on Carbon and Nitrogen Accrual in Natural Forests. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtsuka, T.; Yoshitake, S.; Yashiro, Y.; Shizu, Y.; Iimura, Y.; Yimatsa, N.; Kondo, M.; Adachi, M.; Chen, S.; Cao, R. Changes in Stand Biomass Accumulation and Wood NPP during Secondary Succession: Insights from a 23-Year Study of Forest Dynamics in a Cool-Temperate Secondary Deciduous Forest. Plant Ecol. 2025, 226, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.S.; Kim, A.R.; Lim, B.S.; Seol, J.; An, J.H.; Lim, C.H.; Joo, S.J.; Lee, C.S. Assessment of the Carbon Budget of Local Governments in South Korea. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomotsune, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Kato, Y.; Masuda, R.; Suminokura, N.; Koyama, Y.; Sakamaki, Y.; Koizumi, H. Comparison of Carbon Dynamics among Three Cool-Temperate Forests (Quercus Serrata, Larix Kaempferi and Pinus Densiflora) under the Same Climate Conditions in Japan. J. Environ. Prot. 2019, 10, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becknell, J.M.; Vargas G, G.; Pérez-Aviles, D.; Medvigy, D.; Powers, J.S. Above-ground Net Primary Productivity in Regenerating Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest: Contributions of Rainfall, Forest Age and Soil. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 3903–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Kwon, K.-C. Biomass and Annual Net Production of Quercus Mongolica Stands in Pyungchang and Jecheon Areas. J. Korean For. Soc. 2006, 95, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- The Paris Agreement|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- United Nations General Assembly, 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/united-nations-general-assembly-2015 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Schimel, D.S. Terrestrial Ecosystems and the Carbon Cycle. Glob. Change Biol. 1995, 1, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, A.A.; Zhoolideh, M.; Azadi, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Scheffran, J. Interactions of Land-Use Cover and Climate Change at Global Level: How to Mitigate the Environmental Risks and Warming Effects. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature Annual Report 2016; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP; FAO. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-S.; Kim, D.-U.; Lim, B.-S.; Seok, J.-E.; Kim, G.-S. Vegetation Succession for 12 Years in a Pond Created Restoratively. Biology 2024, 13, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-J.; Lee, C.-M.; Yang, S.-A.; Jung, H.-J.; Lee, J.-M.; Min, Y.-G.; Kim, J.-W.; Myung, H.-H.; Park, H.-C. Estimation of Soil Microbiological Respiration Volume in Forest Ecosystem in the Sobaeksan National Park of Korea. J. Korean Soc. Environ. Restor. Technol. 2023, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.P.; Best, M.J.; Betts, R.A. Climate Change in Cities Due to Global Warming and Urban Effects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.S.; Joo, S.J.; Lee, C.S. Seasonal Variation of Soil Respiration in the Mongolian Oak (Quercus mongolica Fisch. Ex Ledeb.) Forests at the Cool Temperate Zone in Korea. Forests 2020, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S. Disturbance Regime of the Pinus Densiflora Forest in Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 1995, 18, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S. Regeneration Process after Disturbance of the Pinus Densiflora Forest in Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 1995, 18, 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Chun, Y.M.; Lee, H.; Pi, J.H.; Lim, C.H. Establishment, Regeneration, and Succession of Korean Red Pine (Pinus densiflora S. et Z.) Forest in Korea; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1-78984-801-6. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tong, S. Emergence and Growth Performance of Bolboschoenus planiculmis Varied in Response to Water Level and Soil Planting Depth: Implications for Wetland Restoration Using Tuber Transplantation. Aquat. Bot. 2018, 148, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H.; Pi, J.H.; Kim, A.R.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, K.S.; You, Y.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, K.D.; Moon, J.S.; Lee, C.S. Diagnostic Evaluation and Preparation of the Reference Information for River Restoration in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Site | Stand Age (Years) | Aspect | Elevation (m) | Slope (°) | Mean Temperature (°C) | Mean Precipitation (mm) | Parent Rock | Soil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mt. Galmi | 35 | W | 150 | 20 | 12.5 | 1292.6 | Metamorphic | Brown forest |

| Mt. Sori | 43 | NE | 154 | 20 | 11.7 | 1383.6 | Metamorphic | Brown forest |

| Mt. Suri | 26 | S | 56 | 15 | 13.3 | 1327.6 | Metamorphic | Brown forest |

| Mt. Deogyu | 76 | S | 713 | 20 | 11.6 | 1105.3 | Granite | Brown forest |

| Species | Equation | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus rigida | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.22D2.116 | [26] |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.004D2.814 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.003D2.784 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.063D2.285 | ||

| Pinus densiflora | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.235D2.071 | |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.004D2.748 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.054D1.561 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.031D2.279 | ||

| Quercus serrata | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.177D2.195 | |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.003D3.265 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.002D2.713 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.4D1.676 | ||

| Quercus variabilis | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.186D2.184 | |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.035D2.293 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.61D2.456 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.077D2.199 | ||

| Quercus mongolica | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.595D1.766 | |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.007D2.970 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.052D3.262 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.691D1.526 | ||

| Castanea crenata | Stem | Y(kg) = 0.0003D4.217 | |

| Branch | Y(kg) = 0.010D3.006 | ||

| Leaf | Y(kg) = 0.261D1.199 | ||

| Root | Y(kg) = 0.130D2.159 | ||

| Prunus sargentii | Y(kg) = 0.3421D2.1813 | [27,28] | |

| Styrax obassia | Y(kg) = 0.1412D2.4976 | ||

| Site | NPP (tonC·ha−1·yr−1) | Heterotrophic Respiration (tonC·ha−1·yr−1) | NEP (tonC·ha−1·yr−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mt. Galmi | 4.88 | 0.50 | 4.39 |

| Community | Country | NPP | Heterotrophic Respiration | NEP | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. rigida | Korea | 4.27 (20 s) | 0.50 | 4.39 | Current study |

| 4.88 (30 s) | |||||

| 4.32 (40 s) | |||||

| 2.30 (70 s) | |||||

| P. rigida | Korea | 7.2 | 4.9 | 2.3 | [39] |

| 8.6 | 4.6 | 4.0 | |||

| P. densiflora | Korea | 6.4 | 4.1 | 2.3 | [39] |

| 9.4 | 6.7 | 2.7 | |||

| Japan | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 3.1 | 2.9 ± 3.2 | [38] | |

| 5.3 | 2.1 | 3.2 | [40] | ||

| Quercus spp. | Costa Rica | 7.8 | [41] | ||

| Q. acutissima | Korea | 12.4 | 4.8 | 7.6 | [39] |

| 9.6 | 4.4 | 5.2 | |||

| Q. mongolica | Korea | 6.9 | 4.7 | 2.2 | [39] |

| 8.7 | - | - | [42] | ||

| 7.1 | - | - | |||

| 10.6 | - | - | |||

| Q. serrata | Japan | 4.6 | 4.1 | 0.5 | [40] |

| Larix kaempferi | Korea | 7.1 | 3.1 | 4.0 | [39] |

| Japan | 3.2 | 2.3 | 0.9 | [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.S.; Seok, J.; Kang, G.T.; Lim, B.S.; Joo, S.J. Evaluating the Carbon Budget and Seeking Alternatives to Improve Carbon Absorption Capacity at Pinus rigida Plantations in South Korea. Forests 2025, 16, 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121860

Lee CS, Seok J, Kang GT, Lim BS, Joo SJ. Evaluating the Carbon Budget and Seeking Alternatives to Improve Carbon Absorption Capacity at Pinus rigida Plantations in South Korea. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121860

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Chang Seok, Jieun Seok, Gyu Tae Kang, Bong Soon Lim, and Seung Jin Joo. 2025. "Evaluating the Carbon Budget and Seeking Alternatives to Improve Carbon Absorption Capacity at Pinus rigida Plantations in South Korea" Forests 16, no. 12: 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121860

APA StyleLee, C. S., Seok, J., Kang, G. T., Lim, B. S., & Joo, S. J. (2025). Evaluating the Carbon Budget and Seeking Alternatives to Improve Carbon Absorption Capacity at Pinus rigida Plantations in South Korea. Forests, 16(12), 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121860