Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity and Community in Pinus sylvestris Progeny Trials and Its Heritability Among Plus Tree Families

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- analyze the diversity and structure of fungal communities on needles and shoots across Scots pine plus tree progeny trials, considering environmental factors and differences among plus tree genotypes;

- (2)

- evaluate the influence of fungal diversity on tree height growth and needle retention;

- (3)

- investigate the heritability of the fungal communities between the same plus tree families of Scots pine in progeny trials and seed orchards.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites, Sampling Trees and Samples Preparation

Progeny Trees and Sampling Sites

2.2. DNA Extraction and Molecular Analysis

2.3. Bioinformatics

2.3.1. Sequences and Taxonomic Identification

2.3.2. Functional Traits and Relative OTU Frequency

2.4. Statistical Analysis of Fungal Diversity

2.4.1. Alpha Diversity

2.4.2. Beta Diversity

2.4.3. Analyses of Fungal Diversity and Tree Height

2.5. Heritability

3. Results

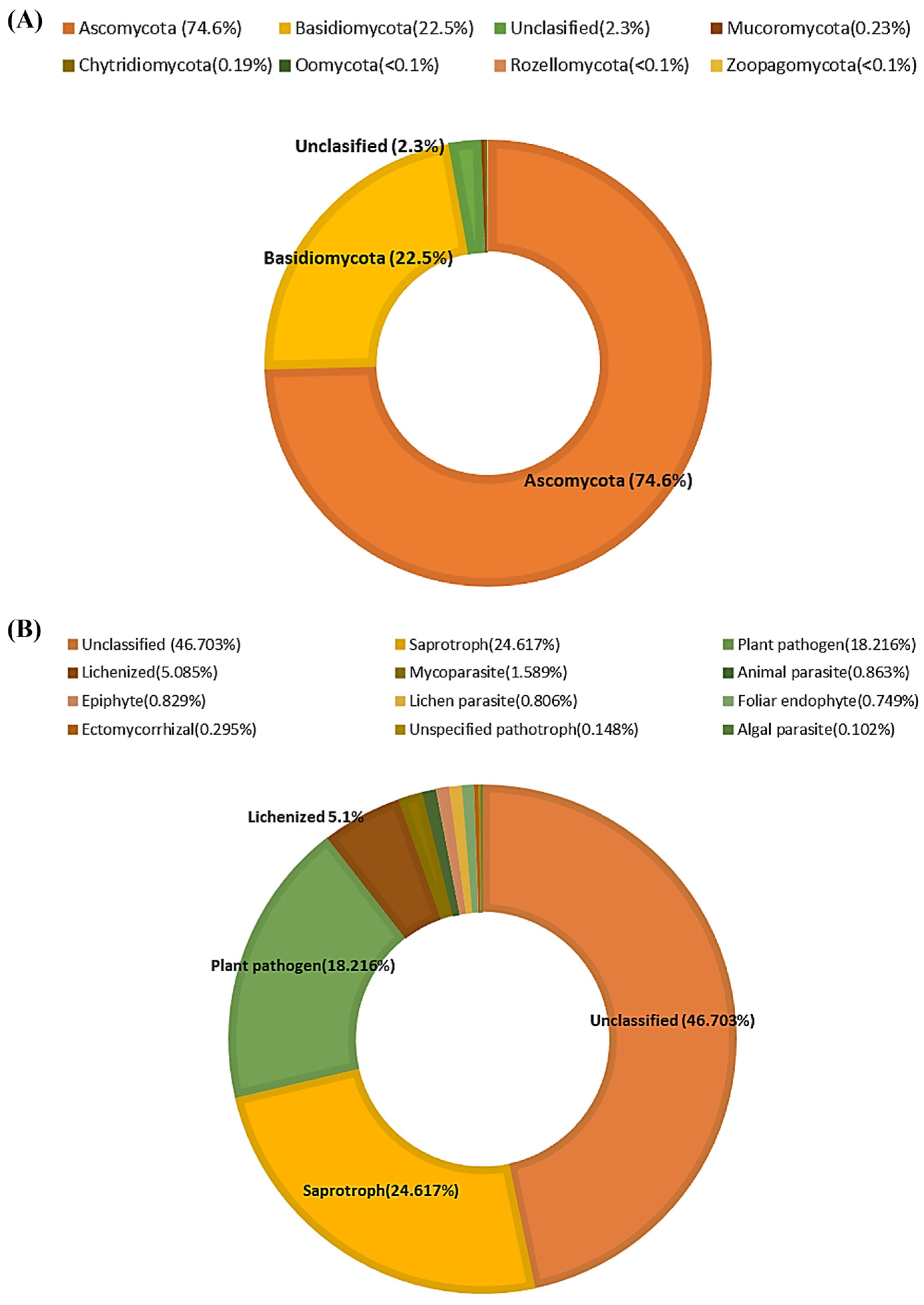

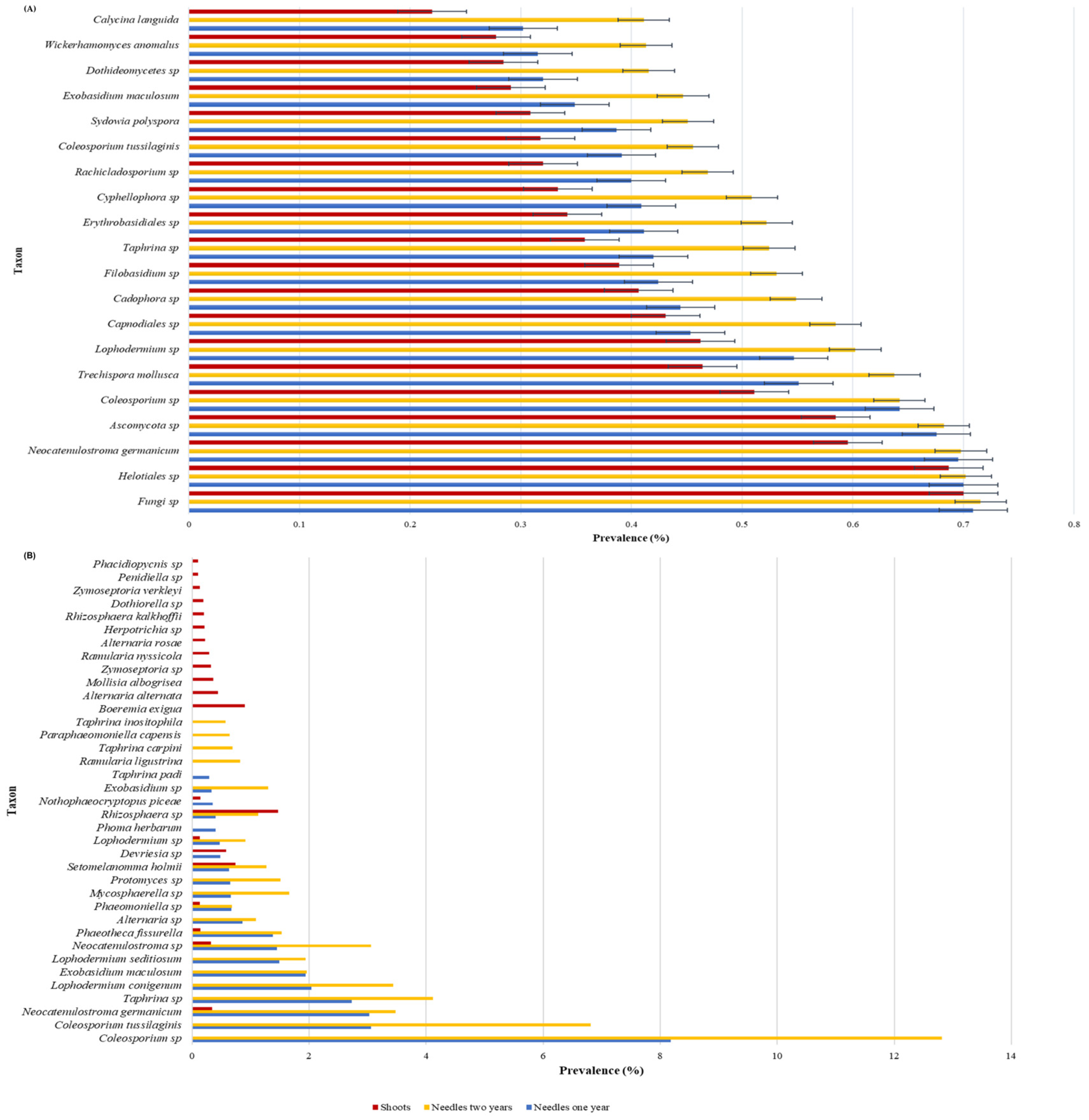

3.1. Taxonomic Classification of Fungi from Needles and Shoots of Scots Pine Progenies

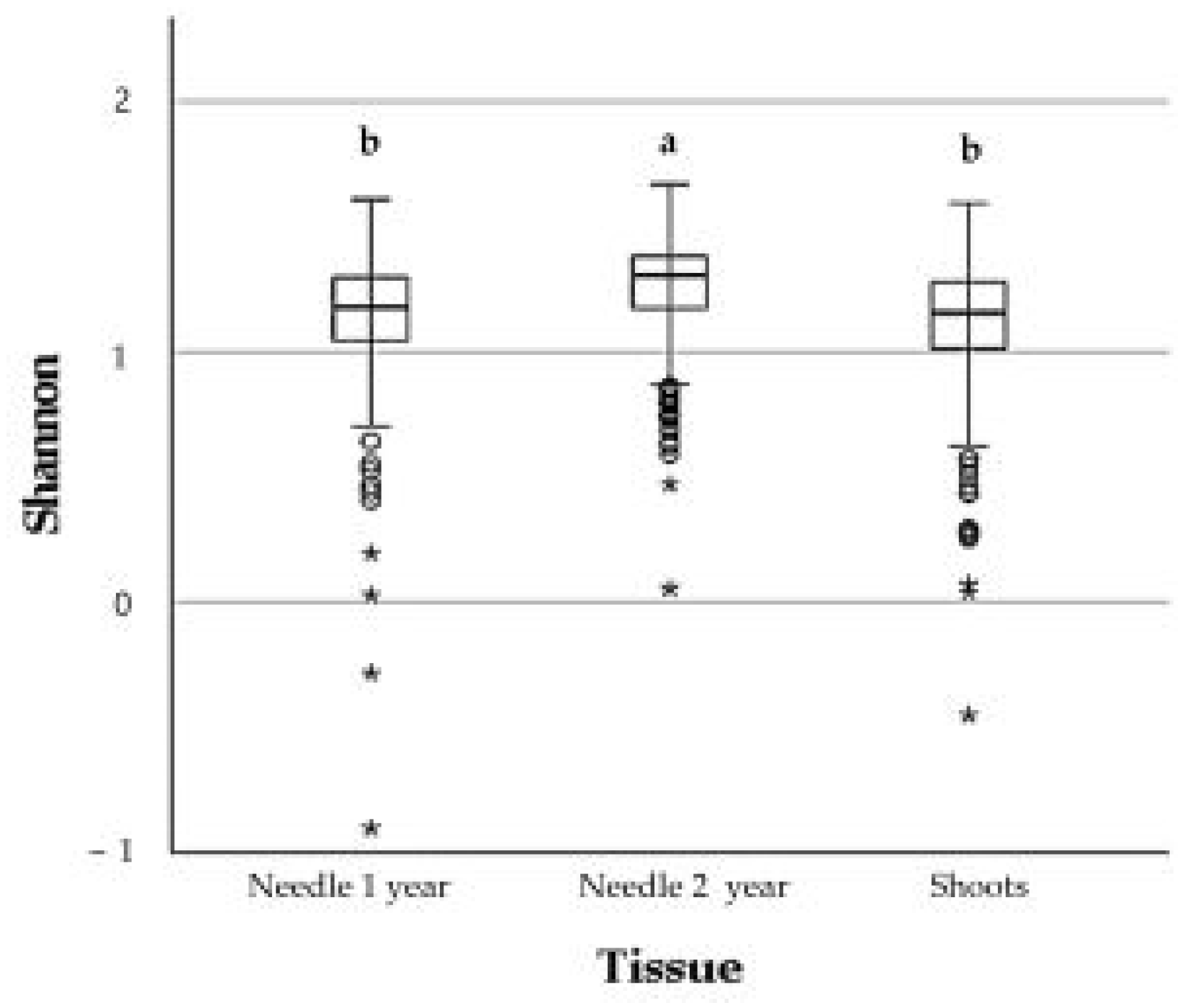

3.2. Overall Fungal Alpha Diversity on Progeny Trees

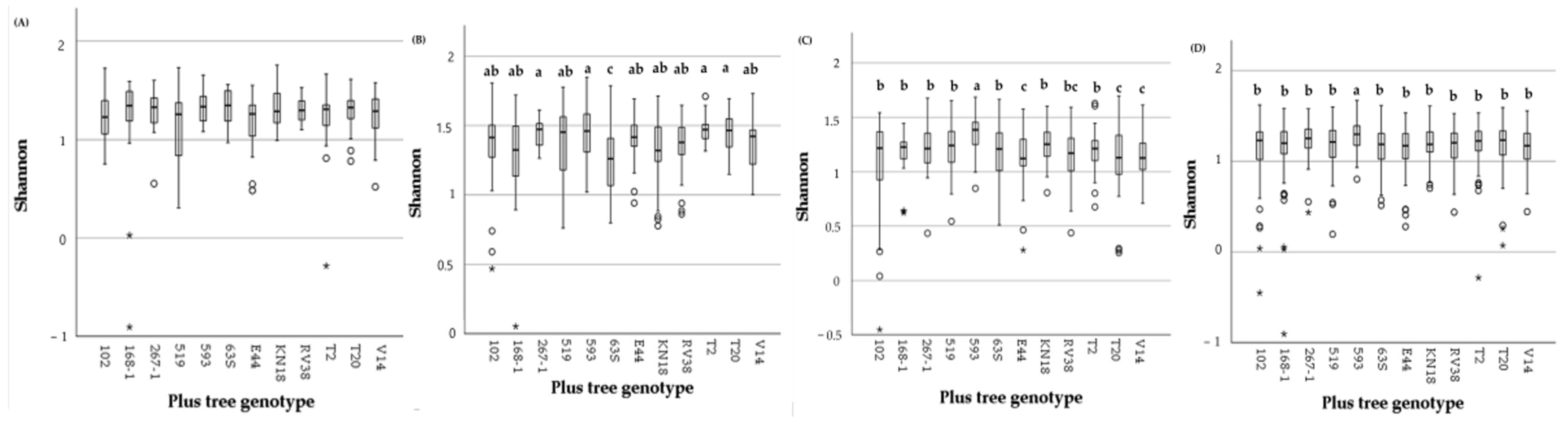

3.3. Fungal Overall Alpha Diversity on Pine Plus Tree Genotype and Environmental Variables in Needles and Shoots

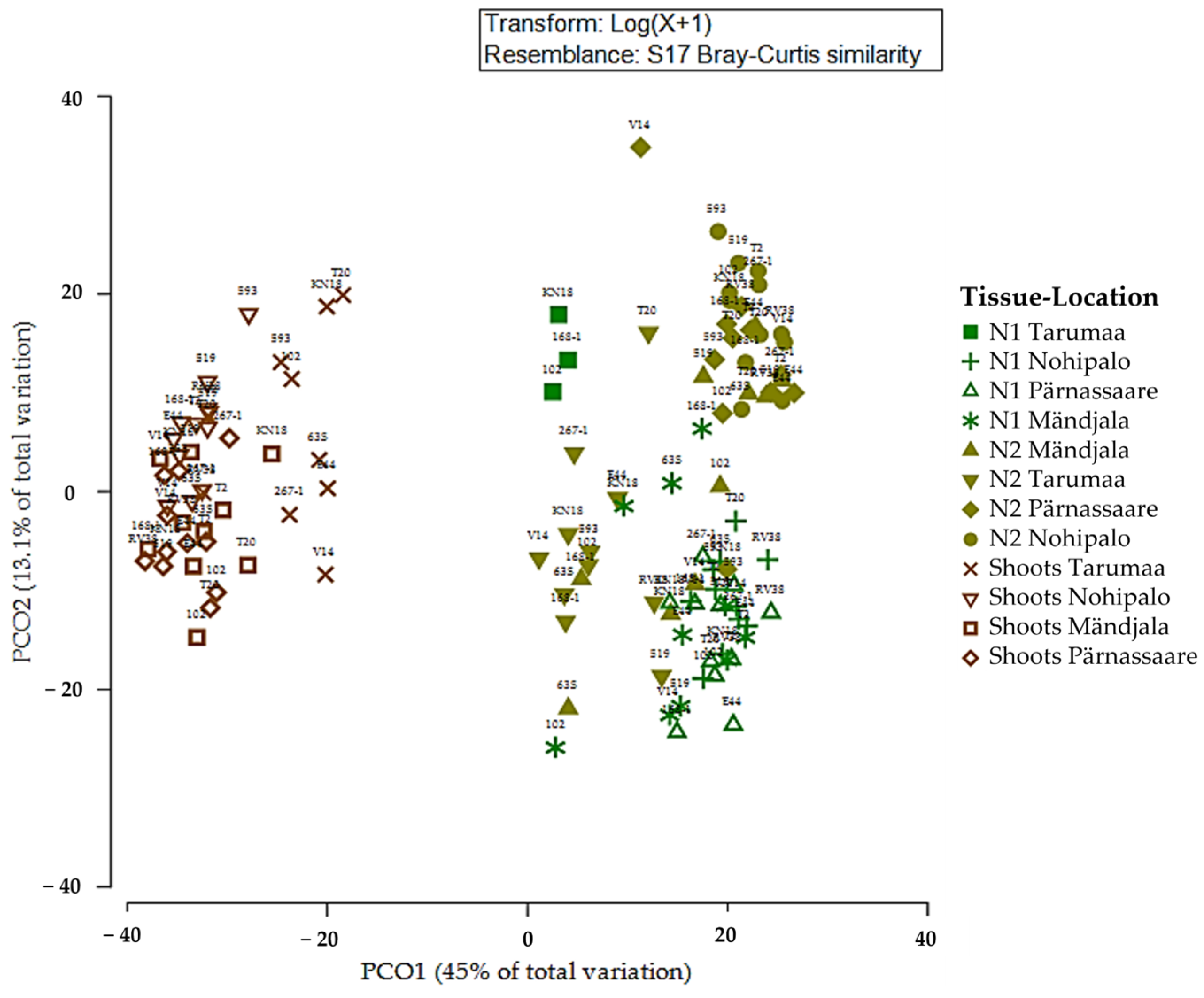

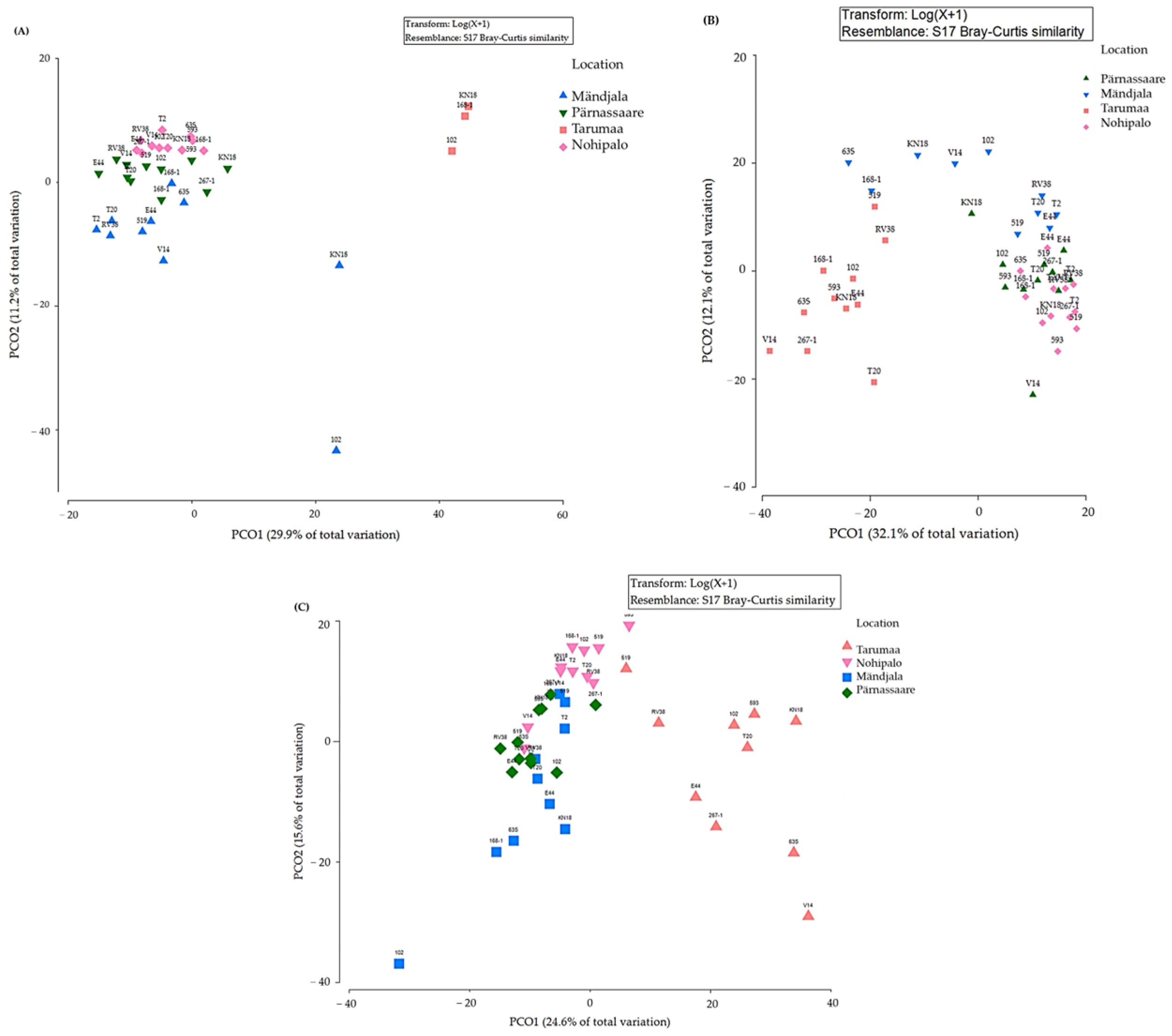

3.4. Fungal Community (Beta Diversity) of Pine Plus Tree Genotype and Tree Tissue Type

3.5. Fungal Community and Multivariate Tissue Analysis

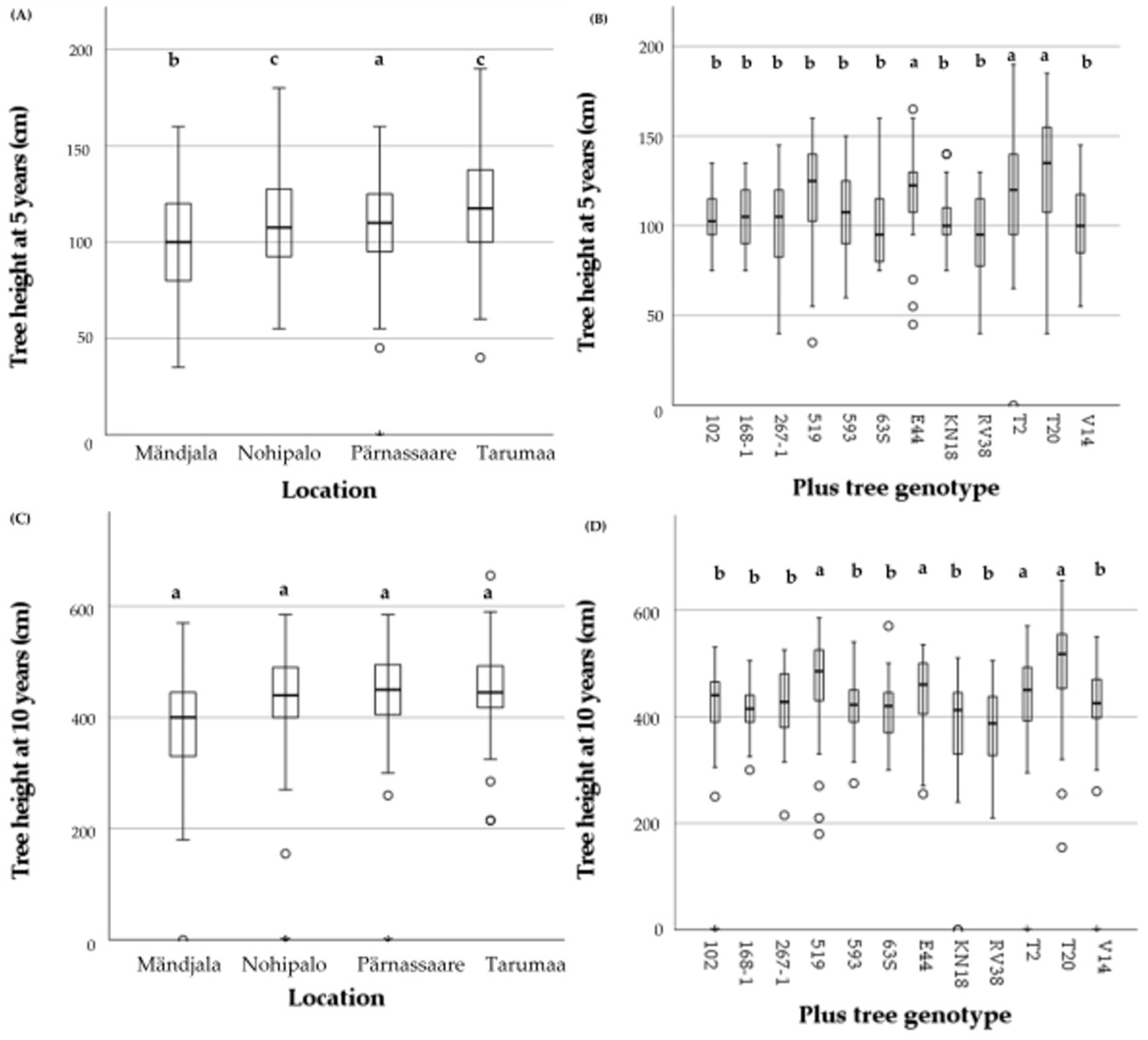

3.6. Scots Pine Plus Tree Height According to Age, Location, and Genotype

3.7. Correlation of Fungal Diversity with Tree Height and Needle Retention of Scots Pine Plus Tree Genotipes

3.8. Scots Pine Plus Tree Heritability

4. Discussion

4.1. Fungal Diversity and Composition of One- and Two-Year-Old Needles and Shoots

4.2. Environmental vs. Genetic Effects

4.3. Fungal Diversity Effect to Tree Growth (2022) and Needle Retention (2022) in Progenies of Scots Pine

4.4. Fungal Heritability Among Plus Tree Families

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldrian, P.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Kohout, P. Forest Microbiome and Global Change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.L.; Gibbs, D.A.; Baccini, A.; Birdsey, R.A.; de Bruin, S.; Farina, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.C.; Herold, M.; Houghton, R.A.; et al. Global Maps of Twenty-First Century Forest Carbon Fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichta, J.; Vacek, S.; Vacek, Z.; Cukor, J.; Mikeska, M.; Bílek, L.; Šimůnek, V.; Gallo, J.; Brabec, P. Importance and Potential of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in 21 St Century. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2023, 69, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksyn, J.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Reich, P.B. Adaptation to Changing Environment in Scots Pine Populations across a Latitudinal Gradient. Silva Fenn. 1998, 32, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, A.K.; Boratyńska, K.; Dering, M.; Sobierajska, K.I.; Ok, T.; Romo, A.; Boratyński, A. Distance between South-European and South-West Asiatic Refugial Areas Involved Morphological Differentiation: Pinus sylvestris Case Study. Plant Syst. Evol. 2014, 300, 1487–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowska, W.B.; Wójkiewicz, B.; Lewandowski, A.; László, R.; Wachowiak, W. Genetic Variation of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in Eurasia: Impact of Postglacial Recolonization and Human-Mediated Gene Transfer. Ann. For. Sci. 2023, 80, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.; Baker, S.C.; Bauhus, J.; Beese, W.J.; Brodie, A.; Kouki, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Lõhmus, A.; Pastur, G.M.; Messier, C.; et al. Retention Forestry to Maintain Multifunctional Forests: A World Perspective. Bioscience 2012, 62, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Zanuso, E.; Genisheva, Z.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A. Green and Sustainable Valorization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Pinus By-Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoai, N.; Duc, H.; Thao, D.; Orav, A.; Raal, A. Selectivity of Pinus sylvestris Extract and Essential Oil to Estrogen-Insensitive Breast Cancer Cells Pinus sylvestris against Cancer Cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Baldrian, P.; Tedersoo, L. Mycobiome Diversity: High-Throughput Sequencing and Identification of Fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terhonen, E.; Blumenstein, K.; Kovalchuk, A.; Asiegbu, F.O. Forest Tree Microbiomes and Associated Fungal Endophytes: Functional Roles and Impact on Forest Health. Forests 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Chen, Y.J.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Jiang, H.B.; Lin, C.G.; Norphanphoun, C.; Sysouphanthong, P.; Pem, D.; et al. The Numbers of Fungi: Is the Descriptive Curve Flattening? Fungal Divers. 2020, 103, 219–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Soytong, K. Understanding Microfungal Diversity-a Critique. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2007, 28, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Peay, K.G.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Elizabeth Arnold, A. Not Every Fungus Is Everywhere: Scaling to the Biogeography of Fungal–Plant Interactions across Roots, Shoots and Ecosystems. New Phytol. 2010, 185, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallad, G.E.; Goodman, R.M. Systemic Acquired Resistance and Induced Systemic Resistance in Conventional Agriculture. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1920–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, J.; Menkis, A. Fungal Diversity in the Phyllosphere of Pinus Heldreichii H. Christ-An Endemic and High-Altitude Pine of the Mediterranean Region. Diversity 2020, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčiulynienė, D.; Marčiulynas, A.; Mishcherikova, V.; Lynikienė, J.; Gedminas, A.; Franic, I.; Menkis, A. Principal Drivers of Fungal Communities Associated with Needles, Shoots, Roots and Adjacent Soil of Pinus sylvestris. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.R. Prioritizing Host Phenotype to Understand Microbiome Heritability in Plants. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, H.; et al. Plant Phenotypic Traits Eventually Shape Its Microbiota: A Common Garden Test. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterseher, M.; Siddique, A.B.; Brachmann, A.; Peršoh, D. Diversity and Composition of the Leaf Mycobiome of Beech (Fagus sylvatica) Are Affected by Local Habitat Conditions and Leaf Biochemistry. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber-Rosenberg, I.; Rosenberg, E. Role of Microorganisms in the Evolution of Animals and Plants: The Hologenome Theory of Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.P.; Bruijning, M.; Forsberg, S.K.G.; Ayroles, J.F. The Microbiome Extends Host Evolutionary Potential. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D. The Epidemiology and Evolution of Symbionts with Mixed-Mode Transmission. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.A.; Frederickson, M.E.; Stinchcombe, J.R. Genetic Architecture of Heritable Leaf Microbes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0061024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.A.; Oliva, J.; Elfstrand, M.; Boberg, J.; Capador-Barreto, H.D.; Karlsson, B.; Berlin, A. Host Genotype Interacts with Aerial Spore Communities and Influences the Needle Mycobiome of Norway Spruce. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 3640–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Ling, N.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Ning, H.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S.; Vandenkoornhuyse, P. Seed-Borne, Endospheric and Rhizospheric Core Microbiota as Predictors of Plant Functional Traits across Rice Cultivars Are Dominated by Deterministic Processes. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2047–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Singh, B.K.; He, J.-Z.; Han, Y.-L.; Li, P.-P.; Wan, L.-H.; Meng, G.-Z.; Liu, S.-Y.; Wang, J.-T.; Wu, C.-F.; et al. Plant Developmental Stage Drives the Differentiation in Ecological Role of the Maize Microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusemann, P.; Schnittler, M.; Nilsson, R.H.; Jumpponen, A.; Dahl, M.B.; Würth, D.G.; Buras, A.; Wilmking, M.; Unterseher, M. Habitat Conditions and Phenological Tree Traits Overrule the Influence of Tree Genotype in the Needle Mycobiome-Picea glauca System at an Arctic Treeline Ecotone. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazis, R.; Chaverri, P. Wild Trees in the Amazon Basin Harbor a Great Diversity of Beneficial Endosymbiotic Fungi: Is This Evidence of Protective Mutualism? Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-F.; Li, J.; Huang, J.-A.; Liu, Z.-H.; Xiong, L.-G. Review: Research Progress on Seasonal Succession of Phyllosphere Microorganisms. Plant Sci. 2023, 338, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudgers, J.A.; Afkhami, M.E.; Bell-Dereske, L.; Chung, Y.A.; Crawford, K.M.; Kivlin, S.N.; Mann, M.A.; Nuñez, M.A. Climate Disruption of Plant-Microbe Interactions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2020, 51, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, K.; Mullett, M.S.; Solheim, H.; Barnes, I.; Müller, M.M.; Hantula, J.; Vuorinen, M.; Kačergius, A.; Markovskaja, S.; Musolin, D.L.; et al. Looking for Relationships between the Populations of Dothistroma septosporum in Northern Europe and Asia. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018, 110, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.M.; Hamberg, L.; Morozova, T.; Sizykh, A.; Sieber, T.; Wingfield, B.D. Adaptation of Subpopulations of the Norway Spruce Needle Endophyte Lophodermium piceae to the Temperature Regime. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laas, M.; Adamson, K.; Barnes, I.; Janoušek, J.; Mullett, M.S.; Adamčíková, K.; Akiba, M.; Beenken, L.; Braganca, H.; Bulgakov, T.S.; et al. Diversity, Migration Routes, and Worldwide Population Genetic Structure of Lecanosticta acicola, the Causal Agent of Brown Spot Needle Blight. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1620–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubby, K.; Adamčikova, K.; Adamson, K.; Akiba, M.; Barnes, I.; Boroń, P.; Bragança, H.; Bulgakov, T.; Burgdorf, N.; Capretti, P.; et al. The Increasing Threat to European Forests from the Invasive Foliar Pine Pathogen, Lecanosticta acicola. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 536, 120847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeste, A.; Blanco, J.A.; Imbert, J.B.; Zozaya-Vela, H.; Elizalde-Arbilla, M. Pinus sylvestris L. and Fagus sylvatica L. Effects on Soil and Root Properties and Their Interactions in a Mixed Forest on the Southwestern Pyrenees. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 481, 118726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, A.V.; Pérez-Luque, A.J.; Fernández-López, M. Root-Associated Microbiota of Decline-Affected and Asymptomatic Pinus sylvestris Trees. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, A.V.; Fernández-González, A.J.; Villadas, P.J.; Mercado-Blanco, J.; Pérez-Luque, A.J.; Fernández-López, M. Mediterranean Pine Forest Decline: A Matter of Root-Associated Microbiota and Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Xiong, C.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Q.L.; Ma, B.; Zhou, S.Y.D.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.M.; Cui, H.L.; Duan, G.L. Impacts of Global Change on the Phyllosphere Microbiome. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agler, M.T.; Ruhe, J.; Kroll, S.; Morhenn, C.; Kim, S.T.; Weigel, D.; Kemen, E.M. Microbial Hub Taxa Link Host and Abiotic Factors to Plant Microbiome Variation. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bálint, M.; Bartha, L.; O’Hara, R.B.; Olson, M.S.; Otte, J.; Pfenninger, M.; Robertson, A.L.; Tiffin, P.; Schmitt, I. Relocation, High-Latitude Warming and Host Genetic Identity Shape the Foliar Fungal Microbiome of Poplars. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.R.; Lundberg, D.S.; Del Rio, T.G.; Tringe, S.G.; Dangl, J.L.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Host Genotype and Age Shape the Leaf and Root Microbiomes of a Wild Perennial Plant. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhonen, E.; Marco, T.; Sun, H.; Jalkanen, R.; Kasanen, R.; Vuorinen, M.; Asiegbu, F. The Effect of Latitude, Season and Needle-Age on the Mycota of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) in Finland. Silva Fenn. 2011, 45, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenance and Progeny Trials|World Agroforestry|Transforming Lives and Landscapes with Trees. Available online: https://www.worldagroforestry.org/publication/provenance-and-progeny-trials-0 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Verbylaitė, R.; Aravanopoulos, F.A.; Baliuckas, V.; Juškauskaitė, A.; Ballian, D. Can a Forest Tree Species Progeny Trial Serve as an Ex Situ Collection? A Case Study on Alnus Glutinosa. Plants 2023, 12, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouan, D. Effective Temperature. In Encyclopedia of Astrobiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 479–480. [Google Scholar]

- Length of the Vegetation Period—SMHI. Available online: https://www.smhi.se/en/climate/tools-and-inspiration/climate-indicators/length-of-the-vegetation-period (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Agan, A.; Solheim, H.; Adamson, K.; Hietala, A.M.; Tedersoo, L.; Drenkhan, R. Seasonal Dynamics of Fungi Associated with Healthy and Diseased Pinus sylvestris Needles in Northern Europe. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal-Arias, C.E.; Adamson, K.; Ahto, A.; Maaten, T.; Rein, D. Fungal Diversity and Composition in Pinus sylvestris Needles Are Influenced by Host Genotype and Seed Orchard Location. Eur. J. For. Res. 2025; Accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Drenkhan, R.; Solheim, H.; Bogacheva, A.; Riit, T.; Adamson, K.; Drenkhan, T.; Maaten, T.; Hietala, A.M. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus Is a Leaf Pathogen of Local Fraxinus Species in the Russian Far East. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agan, A.; Drenkhan, R.; Adamson, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Solheim, H.; Børja, I.; Matsiakh, I.; Timmermann, V.; Nagy, N.E.; Hietala, A.M. The Relationship between Fungal Diversity and Invasibility of a Foliar Niche—The Case of Ash Dieback. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Anslan, S. Towards PacBio-based Pan-eukaryote Metabarcoding Using Full-length ITS Sequences. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2019, 11, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global Diversity and Geography of Soil Fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME Improves Sensitivity and Speed of Chimera Detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Ryberg, M.; Hartmann, M.; Branco, S.; Wang, Z.; Godhe, A.; De Wit, P.; Sanchezgarcia, M.; Ebersberger, I.; De Sousa, F.; et al. Improved Software Detection and Extraction of ITS1 and ITS2 from Ribosomal ITS Sequences of Fungi and Other Eukaryotes for Analysis of Environmental Sequencing Data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Hiiesalu, I.; Tedersoo, L. PipeCraft: Flexible Open-Source Toolkit for Bioinformatics Analysis of Custom High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing Data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, e234–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, W. Sequence Analysis CD-HIT: Accelerated for Clustering the next-Generation Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, R.H.; Abarenkov, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bahram, M.; Bates, S.T.; Bruns, T.D.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Callaghan, T.M.; et al. Towards a Unified Paradigm for Sequence-Based Identification of Fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 5271–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Põlme, S.; Abarenkov, K.; Henrik Nilsson, R.; Lindahl, B.D.; Engelbrecht Clemmensen, K.; Kauserud, H.; Nguyen, N.; Kjøller, R.; Bates, S.T.; Baldrian, P.; et al. FungalTraits: A User-Friendly Traits Database of Fungi and Fungus-like Stramenopiles. Fungal Divers. 2021, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kers, J.G.; Saccenti, E. The Power of Microbiome Studies: Some Considerations on Which Alpha and Beta Metrics to Use and How to Report Results. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 796025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Gorley RN PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gorley, R.N. Clarke KR PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, B.L.; Gatti, D.M.; Ballinger, M.A.; Lin, D.; Phifer-Rixey, M.; Sheehan, M.J.; Suzuki, T.A.; Wooldridge, L.K.; Frempong, H.O.; Lawal, R.A.; et al. Into the Wild: A Novel Wild-Derived Inbred Strain Resource Expands the Genomic and Phenotypic Diversity of Laboratory Mouse Models. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Hill, W.G.; Wray, N.R. Heritability in the Genomics Era—Concepts and Misconceptions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, H.; Aylor, D.L.; Carpenter, D.E.; Peck, B.C.; Chines, P.; Ostrowski, L.E.; Chesler, E.J.; Churchill, G.A.; de Villena, F.P.M.; Kelada, S.N.P. Genetic Regulation of Zfp30, CXCL1, and Neutrophilic Inflammation in Murine Lung. Genetics 2014, 198, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangiorgio, D.; Cáliz, J.; Mattana, S.; Barceló, A.; De Cinti, B.; Elustondo, D.; Hellsten, S.; Magnani, F.; Matteucci, G.; Merilä, P.; et al. Host Species and Temperature Drive Beech and Scots Pine Phyllosphere Microbiota across European Forests. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Bres, C.; Jin, G.; Fanin, N. Coniferous Tree Species Identity and Leaf Aging Alter the Composition of Phyllosphere Communities Through Changes in Leaf Traits. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisberg, E.E.; Hildebrandt, U.; Riederer, M.; Hentschel, U. Distinct Phyllosphere Bacterial Communities on Arabidopsis Wax Mutant Leaves. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveau, J.H. A Brief from the Leaf: Latest Research to Inform Our Understanding of the Phyllosphere Microbiome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Ali, A.; Yang, T.; Lin, F.; Mao, Z.; Ye, J.; Fang, S.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Leaf Traits and Temperature Shape the Elevational Patterns of Phyllosphere Microbiome. J. Biogeogr. 2023, 50, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishcherikova, V.; Lynikienė, J.; Marčiulynas, A.; Gedminas, A.; Prylutskyi, O.; Marčiulynienė, D.; Menkis, A. Biogeography of Fungal Communities Associated with Pinus sylvestris L. and Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. along the Latitudinal Gradient in Europe. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva, M.; Georgieva, M.; Dermendzhiev, P.; Velinov, V.; Nachev, R.; Georgiev, G. First Record of the Fungus Setomelanomma holmii (Pleosporales, Phaeosphaeriaceae) on Picea abies in Bulgaria. Hist. Nat. Bulg. 2025, 47, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, A.Y.; Farr, D.F.; Castlebury, L.A.; Shoemaker, R.; Mengistu, A. Setomelanomma Holmii (Pleosporales, Phaeosphaeriaceae) on Living Spruce Twigs in Europe and North America. Can. J. Bot. 2002, 80, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Duan, T. Characterization of Boeremia Exigua Causing Stem Necrotic Lesions on Luobuma in Northwest China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanso, M.; Drenkhan, R. Lophodermium Needle Cast, Insect Defoliation and Growth Responses of Young Scots Pines in Estonia. For. Pathol. 2012, 42, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, R.; Tomešová-Haataja, V.; Fraser, S.; Bradshaw, R.E.; Vahalík, P.; Mullett, M.S.; Martín-García, J.; Bulman, L.S.; Wingfield, M.J.; Kirisits, T.; et al. Global Geographic Distribution and Host Range of Dothistroma Species: A Comprehensive Review. For. Pathol. 2016, 46, 408–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincebourde, S.; Woods, H.A. Climate Uncertainty on Leaf Surfaces: The Biophysics of Leaf Microclimates and Their Consequences for Leaf-Dwelling Organisms. Funct. Ecol. 2012, 26, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, N.; Bortfeld-Miller, M.; Ackermann, M.; Vorholt, J.A. A Synthetic Community Approach Reveals Plant Genotypes Affecting the Phyllosphere Microbiota. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beule, L.; Grüning, M.M.; Karlovsky, P.; L-M-Arnold, A. Changes of Scots Pine Phyllosphere and Soil Fungal Communities during Outbreaks of Defoliating Insects. Forests 2017, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Manninen, M.J.; Asiegbu, F.O. Beneficial Mutualistic Fungus Suillus Luteus Provided Excellent Buffering Insurance in Scots Pine Defense Responses under Pathogen Challenge at Transcriptome Level. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senashova, V.A.; Aniskina, A.A.; Polyakova, G.G. Relationships in the Host Plant–Pathogen System Using the Example of Scots Pine and Facultative Saprotroph Lophodermium Seditiosum Minter, Staley & Millar. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2023, 16, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, I.N. Biotic and Abiotic Factors as Causes of Coniferous Forests Dieback in Siberia and Far East. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2015, 8, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönrogge, K.; Gibbs, M.; Oliver, A.; Cavers, S.; Gweon, H.S.; Ennos, R.A.; Cottrell, J.; Iason, G.R.; Taylor, J. Environmental Factors and Host Genetic Variation Shape the Fungal Endophyte Communities within Needles of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris). Fungal Ecol. 2022, 57–58, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, P.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Szuba, A.; Niestrawska, A.; Mucha, J. The Effects of Pinus sylvestris L. Geographical Origin on the Community and Co-Occurrence of Fungal and Bacterial Endophytes in a Common Garden Experiment. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0080724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millberg, H.; Boberg, J.; Stenlid, J.; Dighton, J. Changes in Fungal Community of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) Needles along a Latitudinal Gradient in Sweden. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, R.; Paasch, B.C.; Liber, J.A.; He, S.Y. Phyllosphere Microbiome. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 539–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, N.; Herre, E.A.; Clay, K. Foliar Endophytic Fungi Alter Patterns of Nitrogen Uptake and Distribution in Theobroma Cacao. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Tyagi, A.; Bae, H.; Ali, S.; Tyagi, A.; Bae, H. Plant Microbiome: An Ocean of Possibilities for Improving Disease Resistance in Plants. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hong, L.; Ye, W.; Wang, Z.; Shen, H. Phyllosphere Bacterial and Fungal Communities Vary with Host Species Identity, Plant Traits and Seasonality in a Subtropical Forest. Environ. Microbiomes 2022, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Yang, J.; Ni, S. Microbiome-Mediated Protection against Pathogens in Woody Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, B.K.; Tran, E.H.; Afkhami, M.E. Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity Generates Pervasive Nonadditive Effects on Plant Performance. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 2416–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.C.; Fitt, B.D.L.; Atkins, S.D.; Walters, D.R.; Daniell, T.J. Pathogenesis, Parasitism and Mutualism in the Trophic Space of Microbe-Plant Interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häffner, E.; Konietzki, S.; Diederichsen, E. Keeping Control: The Role of Senescence and Development in Plant Pathogenesis and Defense. Plants 2015, 4, 449–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N. Endophytic Fungi in Forest Trees: Are They Mutualists? Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, R.; Kurkela, T.; Hanso, M. The Relationship between the Needle Age and the Growth Rate in Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris): A Retrospective Analysis by Needle Trace Method (NTM). Eur. J. For. Res. 2006, 125, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Webster, S.; He, S.Y. Growth–Defense Trade-Offs in Plants. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R634–R639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolinelli-Alfonso, M.; Villalobos-Escobedo, J.M.; Rolshausen, P.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Galindo-Sánchez, C.; López-Hernández, J.F.; Hernandez-Martinez, R. Global Transcriptional Analysis Suggests Lasiodiplodia theobromae Pathogenicity Factors Involved in Modulation of Grapevine Defensive Response. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Arias, C.; Sobrino-Plata, J.; Ormeño-Moncalvillo, S.; Gil, L.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Martín, J.A. Endophyte Inoculation Enhances Ulmus minor Resistance to Dutch Elm Disease. Fungal Ecol. 2021, 50, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiring, D.; Adams, G.; McCartney, A.; Edwards, S.; Miller, J.D. A Foliar Endophyte of White Spruce Reduces Survival of the Eastern Spruce Budworm and Tree Defoliation. Forests 2020, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiring, D.; Adams, G.; Flaherty, L.; McCartney, A.; Miller, J.D.; Edwards, S. Influence of a Foliar Endophyte and Budburst Phenology on Survival of Wild and Laboratory-Reared Eastern Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana on White Spruce (Picea glauca). Forests 2019, 10, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanney, J.B.; McMullin, D.R.; Miller, J.D. Toxigenic Foliar Endophytes from the Acadian Forest; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 343–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, Y.; Niiyama, K.; Aiba, S.; Kurokawa, H.; Kondo, S.; Mukai, M.; Mori, A.S.; Saito, S.; Sun, Y.; Umeki, K. The Trait-Mediated Trade-off between Growth and Survival Depends on Tree Sizes and Environmental Conditions. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballaré, C.L.; Austin, A.T. Recalculating Growth and Defense Strategies under Competition: Key Roles of Photoreceptors and Jasmonates. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 3425–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züst, T.; Agrawal, A.A. Trade-Offs Between Plant Growth and Defense Against Insect Herbivory: An Emerging Mechanistic Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcón-Bieto, J.; Talón, M. Fundamentos de Fisiología Vegetal, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Columbus, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Quaiser, A.; Duhamel, M.; Le Van, A.; Dufresne, A. The Importance of the Microbiome of the Plant Holobiont. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehle, C. Height Growth Rate Tradeoffs Determine Northern and Southern Range Limits for Trees. J. Biogeogr. 1998, 25, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. Responses of Forest Trees to Single and Multiple Environmental Stresses from Seedlings to Mature Plants: Past Stress History, Stress Interactions, Tolerance and Acclimation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wallendael, A.; Benucci, G.M.N.; da Costa, P.B.; Fraser, L.; Sreedasyam, A.; Fritschi, F.; Juenger, T.E.; Lovell, J.T.; Bonito, G.; Lowry, D.B. Host Genotype Controls Ecological Change in the Leaf Fungal Microbiome. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasov, T.L.; Lundberg, D.S. The Changing Influence of Host Genetics on the Leaf Fungal Microbiome throughout Plant Development. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Geographical Coordinates | Meteorological Station | Sum of Effective Temperature (SET) (°C) * | Average Temperature of Vegetation Period (AVTP) (°C) ** | Altitude (m.a.s.l)/Location Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mändjala | 58.212886° N, 22.303049° E | Sõrve | 1200 | 15.0 | 3 |

| Pärnassaare | 58.18252° N, 24.924042° E | Pärnu | 1250 | 15.5 | 43–44 |

| Nohipalo | 57.959597° N, 27.355232° E | Võru | 1300 | 15.8 | 53–57 |

| Tarumaa | 59.223592° N, 27.134243° E | Narva | 1150 | 14.8 | 57–59 |

| Analysis | Dependent Variable | Independent Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Kruskal–Wallis | Shannon index | Plus tree genotype, Tissue, Location |

| Generalized Lineal Model | Shannon index | Plus tree genotype, SET, ATVP, Location |

| Spearman | Shannon index; Tree height | Environmental covariates (SET, ATVP, Location), Plus tree genotype |

| PERMANOVA | OTU composition | Plus tree genotype, Tissue, Location |

| ANOSIM | Community dissimilarity (Bray–Curtis) | Grouping factors: Tree tissue type, Location, Plus tree genotype |

| BEST/BIOENV | Community dissimilarity (Bray–Curtis) | Environmental variables: SET, ATVP, Location |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvajal-Arias, C.E.; Agan, A.; Adamson, K.; Maaten, T.; Drenkhan, R. Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity and Community in Pinus sylvestris Progeny Trials and Its Heritability Among Plus Tree Families. Forests 2025, 16, 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121859

Carvajal-Arias CE, Agan A, Adamson K, Maaten T, Drenkhan R. Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity and Community in Pinus sylvestris Progeny Trials and Its Heritability Among Plus Tree Families. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121859

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvajal-Arias, Carel Elizabeth, Ahto Agan, Kalev Adamson, Tiit Maaten, and Rein Drenkhan. 2025. "Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity and Community in Pinus sylvestris Progeny Trials and Its Heritability Among Plus Tree Families" Forests 16, no. 12: 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121859

APA StyleCarvajal-Arias, C. E., Agan, A., Adamson, K., Maaten, T., & Drenkhan, R. (2025). Phyllosphere Fungal Diversity and Community in Pinus sylvestris Progeny Trials and Its Heritability Among Plus Tree Families. Forests, 16(12), 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121859