Transcriptomic Response of Larix kaempferi to Infection Stress from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

2.3. Data Filtering and De Novo Assembly

2.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) and Functional Annotation

2.5. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

2.6. Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

2.7. PPI Analysis and Key Gene Screening

2.8. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

3. Results

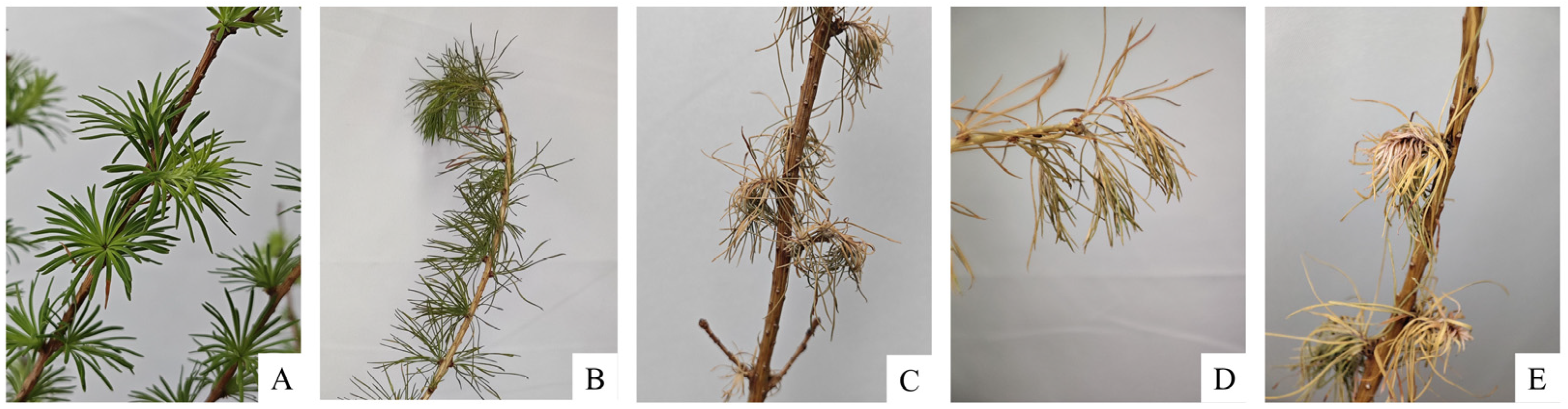

3.1. Symptoms of L. kaempferi

3.2. RNA-Seq Data Evaluation

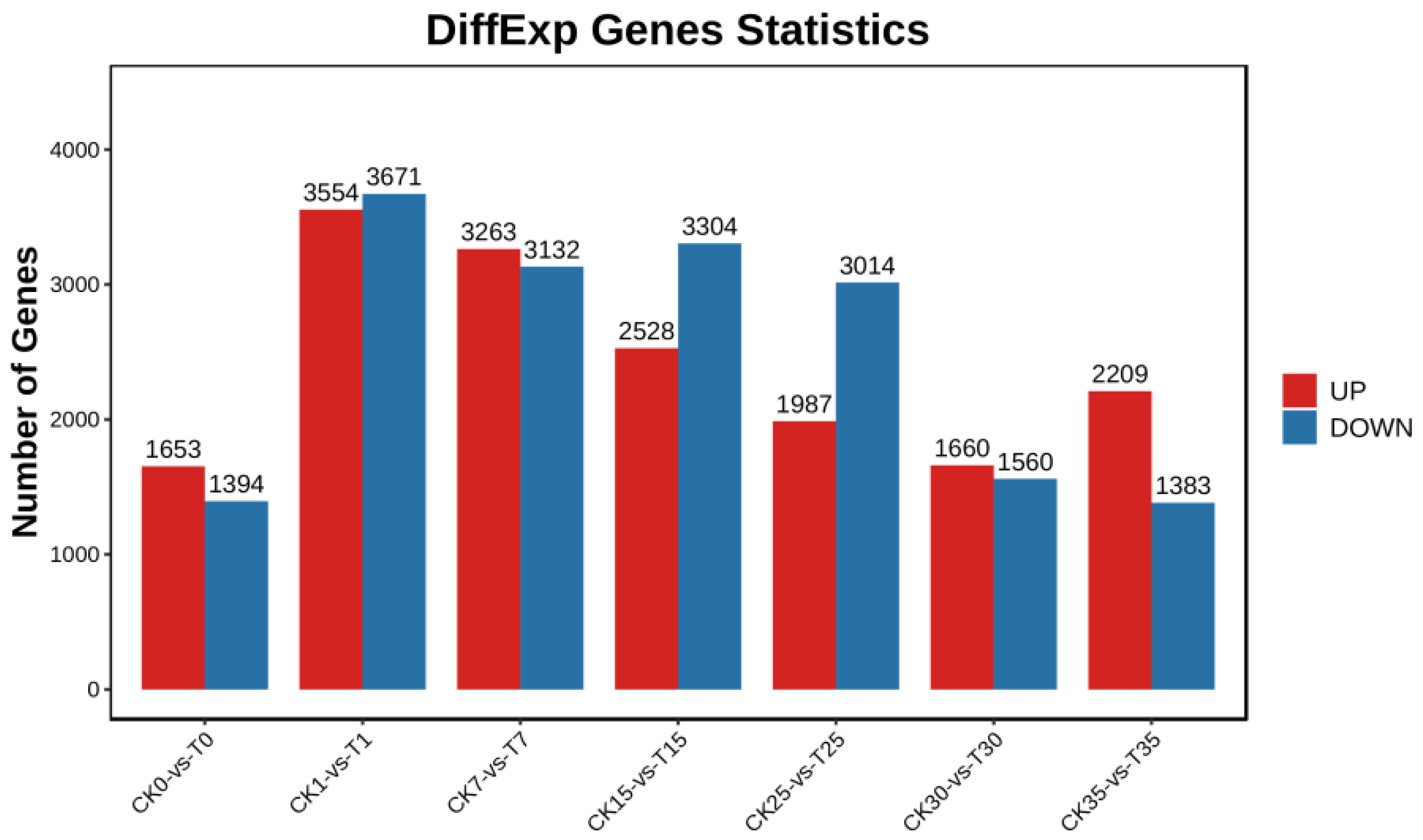

3.3. Gene Expression Patterns of L. kaempfer in Response to B. xylophilus Infection

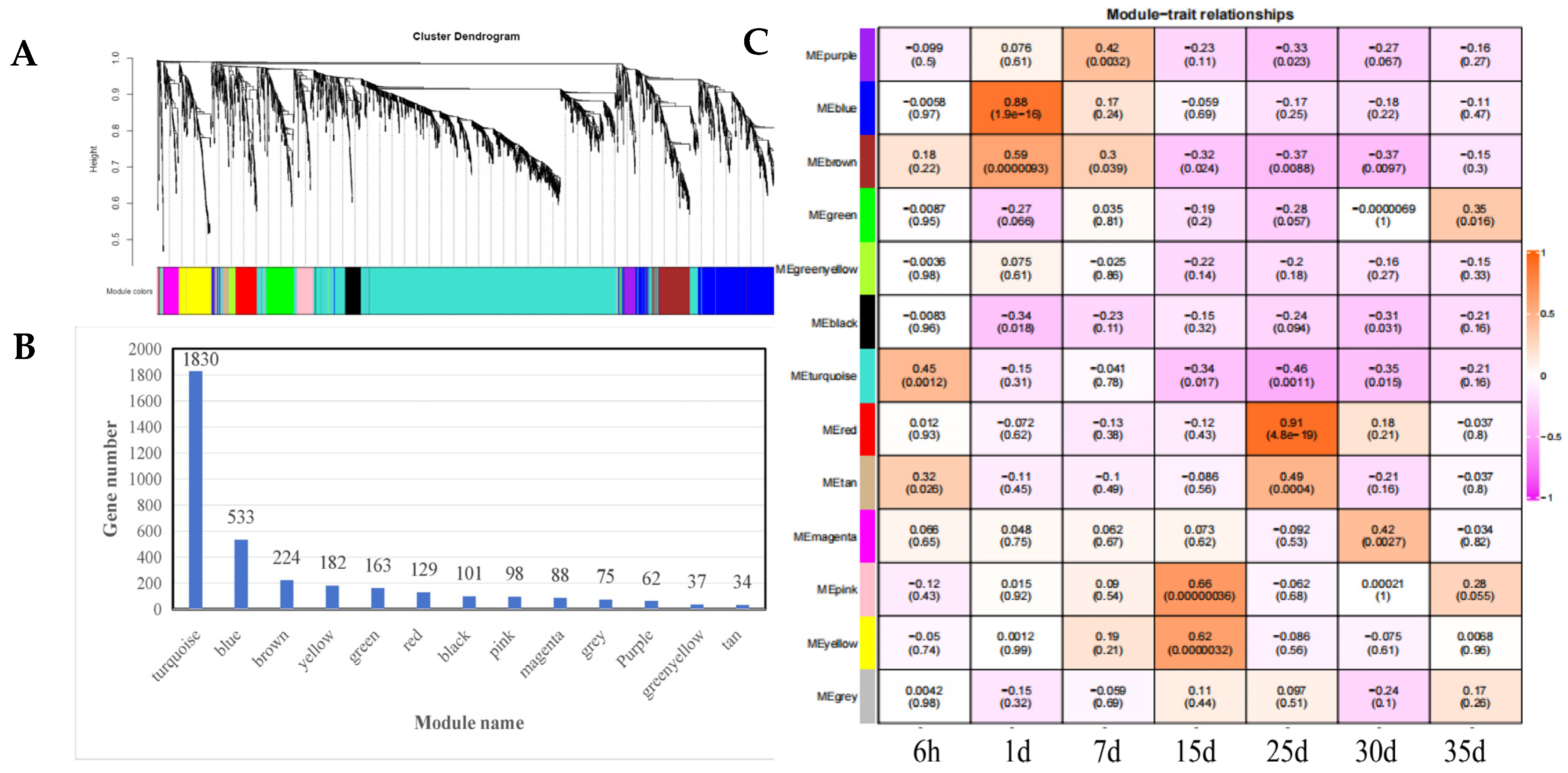

3.4. Construction of Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network and Identification of Key Modules

3.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Key Modules

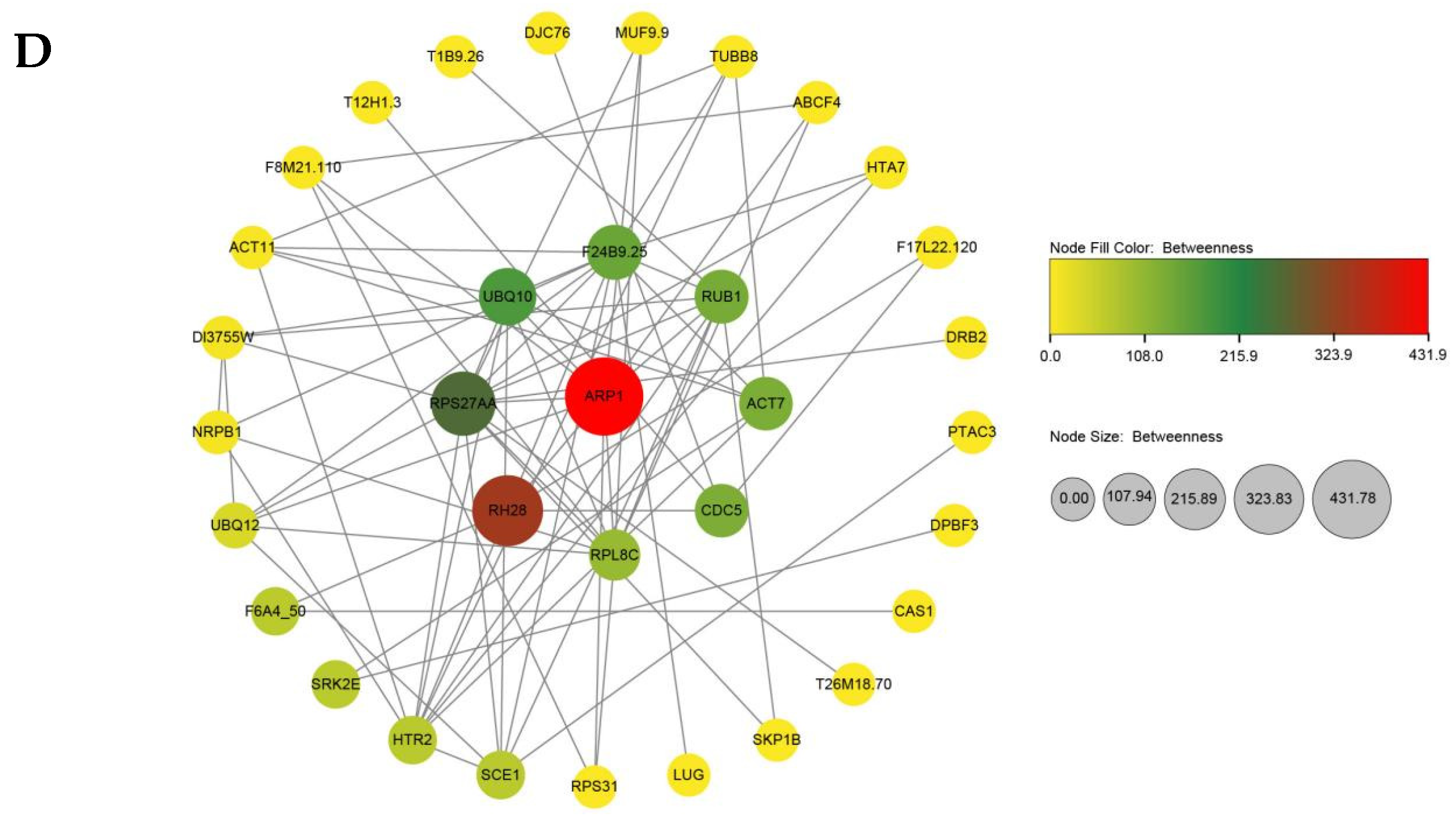

3.6. Identification of Hub Genes by Integrating Protein–Protein Interaction Network

4. Discussion

4.1. The Overall Dynamic Response and Defense Strategy Transformation of Host Transcriptome

4.2. Phased Activation of Defense Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

4.3. Identification and Functional Analysis of Core Defense Gene Network

4.3.1. Resistance Metabolites Synthesis Genes (Terpenoids and Phenylpropanoids)

4.3.2. Protein Homeostasis and Signal Regulation Genes (Ubiquitination and Cytoskeleton)

4.3.3. Gene Expression Regulation Genes (Ribosomes and Histones)

4.3.4. Core Metabolic Node Gene (CSY4)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, T.Y.; Wu, X.Q.; Hu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Rui, L. The Bursaphelenchus xylophilus effector BxML1 targets the cyclophilin protein (CyP) to promote parasitism and virulence in pine. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, K.; Shigesada, N. Spread of the pinewood nematode vectored by the Japanese pine sawyer: Modeling and analytical approaches. Popul. Ecol. 2006, 48, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Lee, H.; Woo, K.S.; Noh, E.W.; Koo, Y.B.; Lee, K.J. Identification of genes upregulated by pinewood nematode inoculation in Japanese red pine. Tree Physiol. 2009, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelleira, A.; Picoaga, A.; Mansilla, J.P.; Aguin, O. Detection of Bursaphelenchus Xylophilus, causal agent of pine wilt disease on Pinus pinaster in northwestern Spain. Plant Dis. 2011, 96, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.R.; Wu, X.Q. Research progress of pine wilt disease. For. Pest Dis. 2022, 41, 1−10. [Google Scholar]

- Droppkin, V.H.; Foudin, A.S. Report of the occurrence of Bursaphelenchus lignicolus-induced pine wilt disease in Missouri. Plant Dis. Rep. 1979, 63, 904–905. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie, A.J.; Venn, T.; Lawson, S.; Nagel, M.; Wardlaw, T.; Cameron, N.; Last, I. An analysis of pest risk and potential economic impact of pine wilt disease to Pinus plantations in Australia. Aust. For. 2018, 81, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, M. Investigation on the cause of pine mortality in Nagasaki. Prefect. Sanrinkoho 1913, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya, Y. History of pine wilt disease in Japan. J. Nematol. 1988, 20, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Wu, H. New host plants and new vector insects found in pine wood nematode in Liaoning. For. Pest Dis. 2018, 37, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Li, H.; Sheng, R.C.; Sun, H.; Sun, S.H.; Chen, F.M. The first record of Monochamus saltuarius (Coleoptera; Cerambycidae) as vector of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and its new potential hosts in China. Insects 2020, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.; Musso, M.; Kain, S.; Willför, S.; Petutschnigg, A.; Schnabel, T. Larch Wood Residues Valorization through Extraction and Utilization of High Value-Added Products. Polymers 2020, 12, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Quan, W.; Zeng, Q.; Van de Peer, Y.; Zhang, S. The Larix kaempferi genome reveals new insights into wood properties. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y. Larch under the condition of natural infection were at the beginning of nematodes. J. For. Dis. 2019, 38, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, R.; Hong, C.; Zhang, W.; Rong, G.; Zhang, X. Isolation and identification of pine wood nematodes from Japanese Larch in Hubei. Res. Temp. For. 2019, 3, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Tian, C.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, S. Preliminary study on the pathogenicity of pine wood nematode to Pinus koraiensis, Pinus tabulaeformis and Larix kaempferi seedlings. China For. Dis. Insect Pests 2025, 44, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Caillot, S.; Rat, S.; Tavernier, M.-L.; Michaud, P.; Kovensky, J.; Wadouachi, A.; Clément, C.; Baillieul, F.; Petit, E. Native and sulfated oligoglucuronans as elicitors of defence-related responses inducing protection against Botrytis cinerea of Vitis vinifera. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, T.; He, S.Y. Innate Immunity in Plants: An Arms Race Between Pattern Recognition Receptors in Plants and Effectors in Microbial Pathogens. Science 2009, 324, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Bin, J.; Wu, B. MAPK in plants. J. Bot. 2004, 21, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- González Víctor, M.; Sebastian, M.; Baulcombe, D.; Puigdomènech, P. Evolution of NBS-LRR Gene Copies among Dicot Plants and its Regulation by Members of the miR482/2118 Superfamily of miRNAs. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, P. Chemical warfare or modulators of defence responses—The function of secondary metabolites in plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Pinto, J.J.; Yephremov, A. Surface lipids and plant defenses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyuka, K.; Rudd, J.J. Cell surface immune receptors: The guardians of the plant’s extracellular spaces. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesto, I.; Sterck, L.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Carrasquinho, I.; Van de Peer, Y.; Miguel, C.M. Insights into the mechanisms implicated in Pinus pinaster resistance to pinewood nematode. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 690857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liang, G.; Huang, A.; Zhang, F.; Guo, W. Comparative study on the mRNA expression of Pinus massoniana infected by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. J. For. Res. 2019, 31, 75–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; Pan, M.; Shen, L.; Ye, J.; Tan, J. Early diagnosis of pine wilt disease in Pinus thunbergii based on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Forests 2023, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Xu, L.; Hao, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Differentially Expressed Genes Associated with Pine Wood Nematode Resistance in Masson Pine (Pinus massoniana Lamb.). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirao, T.; Fukatsu, E.; Watanabe, A. Characterization of resistance to pine wood nematode infection in Pinus thunbergii using suppression subtractive hybridization. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wen, X.; Zhang, X. Transcriptomic response of Pinus massoniana to infection stress from the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.S.; Pinheiro, M.; Silva, A.I.; Egas, C.; Vasconcelos, M.W. Searching for resistance genes to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using high throughput screening. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jeon, H.W.; Jung, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Park, A.R.; Kim, N.; Han, G.; Kim, J.; Seo, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis of pine trees treated with resistance-inducing substances against the nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Genes 2020, 11, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Lv, Y.; Bushley, K.E.; Wickham, J.D.; Gao, S.; Hu, S.; Zhao, L.; Sun, J. Gene family expansion of pinewood nematode to detoxify its host defence chemicals. Mol. Ecol 2020, 29, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Han, H.; Koh, Y.H.; Kim, I.S.; Lee, S.; Shim, D. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Pinus densiflora following inoculation with pathogenic (Bursaphenchus xylophilus) or non-pathogenic nematodes (B. thailandae). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Liu, N.; Wang, F. Methyl jasmonate induced tolerance effect of Pinus koraiensis to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinya, R.; Morisaka, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Ueda, M.; Futai, K. Secretome analysis of the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus reveals the tangled roots of parasitism and its potential for molecular mimicry. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wen, X.; Zhang, X. The changes of microbial communities and key metabolites after early Bursaphelenchus xylophilus invasion of Pinus massoniana. Plants 2022, 11, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, R.; Li, D.; Wang, F. Transcriptomic and Coexpression network analyses revealed pine Chalcone synthase genes associated with pine wood nematode infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, K.; Chen, S.-N.; Su, X. Transcriptomic insights into the efects of CytCo, a novel nematotoxic protein, on the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Guo, K.; Chen, A.; Chen, S.; Lin, H.; Zhou, X. Transcriptomic profling of efects of emamectin benzoate on the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Combined Analysis of Transcriptome and Metabolome in the Early Response of Pinus tabulaeformis to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Master’s thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. Changes in Defense Substances and Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant Pinus massoniana after Inoculation with B. xylophilus. Doctoral Thesis, China Academy of Forestry Sciences, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrenner, A.D.; Gómez, S.; Osorio, S.; Fernie, A.R.; Orians, C.M. Herbivore-induced changes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) primary metabolism: A whole plant perspective. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 37, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.M.; Senthil-Kumar, M.; Tzin, V.; Mysore, K.S. Regulation of primary plant metabolism during plant-pathogen interactions and its contribution to plant defense. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesisy. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, J.H.; Maina, A.; Gomez, I.D.; Cadet, M.; Oeljeklaus, S.; Schiedel, A.C. Cloning, expression and purification of an acetoacetyl CoA thiolase from sunflower cotyledon. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laule, O.; Fürholz, A.; Chang, H.S.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Heifetz, P.B.; Gruissem, W.; Lange, M. Crosstalk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6866–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xu, F.; Song, Q.; Ye, J.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, W. Isolation, characterization and functional analysis of a novel 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase gene (GbHMGS2) from Ginkgo biloba. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.L.; Niu, Y.L.; Huang, H.; He, B.; Ma, L.; Tu, Y.Y.; Tran, V.T.; Zeng, B.; Hu, Z.H. Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase MVD/Erg19 is required for ergosterol biosynthesis, growth, sporulation and stress tolerance in Aspergillus oryzae. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossoni, L.; Hall, S.J.; Eastham, G.; Licence, P.; Stephens, G. The Putative Mevalonate Diphosphate Decarboxylase from Picrophilus torridus Is in Reality a Mevalonate-3-Kinase with High Potential for Bioproduction of Isobutene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 2625–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, S.U.; Park, S.U. Molecular cloning and characterization of mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway genes and triterpene accumulation in Panax ginseng. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2014, 57, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Meng, C.; Xiu, L.; Lao, F.; Pengyuet, Z. Expression of key enzyme genes in saponins biosynthesis and correlation between them and saponins content in different gender types of Eleutherococcus senticosus. Econ. For. Res. 2013, 31, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Xiao, J.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Tian, H.; Zhan, Y. Cloning, expression characteristics of a new FPS gene from birch (Betula platyphylla suk.) and functional identification in triterpenoid synthesis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 154, 112591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delourme, D.; Lacroute, F.; Karst, F. Cloning of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA coding for farnesyl diphosphate synthase by functional complementation in yeast. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 26, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, J.C.; Li, W.C.; Qu, J.T.; Yu, H.Q.; Jiang, F.X.; Fu, F.L. Cloning and characterization of Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene from Anoectochilus. Pak. J. Bot. 2020, 52, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetali, S.D. Terpenes and isoprenoids: A wealth of compounds for global use. Planta 2019, 249, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.H. Analysis of Genetic Transformation and Offspring Traits of Maize with Isopentenyl Pyrophosphate Isomerase Gene. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q. A new isopentenyl di phosphate isomerase gene from sweet potato: Cloning, characterization and color complementation. Biologia 2008, 63, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, F.; Guo, B.; Miao, Z.; Sun, X.; Tang, K. Molecular cloning, expression profiling and functional analyses of a cDNA encoding isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase from Gossypium barbadense. Biosci. Rep. 2009, 29, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Guan, H.; Dai, Z.; Guo, J.; Shen, Y.; Cui, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, L. Functional Analysis of the Isopentenyl Diphosphate Isomerase of Salvia miltiorrhiza via Color Complementation and RNA Interference. Molecules 2015, 20, 20206–20218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Seth, R.; Thakur, S.; Parmar, R.; Masand, M.; Devi, A.; Singh, G.; Dhyani, P.; Choudhary, S.; Sharma, R.K. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis unveils the molecular basis of organ-specific expression of isosteroidal alkaloids biosynthesis in critically endangered Fritillaria roylei Hook. Phytochemistry 2021, 187, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.M.; Murray, G.W.; Batth, T.S.; Prasad, N.; Adams, P.D.; Keasling, J.D.; Petzold, C.J.; Lee, T.S. Application of targeted proteomics and biological parts assembly in E. coli to optimize the biosynthesis of an anti-malarial drug precursor, amorpha-4,11-diene. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 103, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G.; Dudhagi, S.S.; Raizada, S.; Singh, R.K.; Sane, A.P.; Sane, V.A. Phosphomevalonate kinase regulates the MVA/MEP pathway in mango during ripening. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mostafa, S.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Function and Mechanism of Jasmonic Acid in Plant Responses to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, J.; Chang, X.; Liu, D.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; et al. A novel genome sequence of Jasminum sambac helps uncover the molecular mechanism underlying the accumulation of jasmonates. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlting, J.; Hamberger, B.; Million-Rousseau, R.; Werck-Reichhart, D. Cytochromes P450 in phenolic metabolism. Phytochem. Rev. 2006, 5, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, D.J.; Long, M.; Donovan, G.; Fraser, P.D.; Boudet, A.M.; Danoun, S.; Bramley PMBolwell, G.P. Introduction of sense constructs of cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (CYP73A24) in transgenic tomato plants shows opposite effects on flux into stem lignin and fruit flavonoids. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Yassin, N.B.M.; Park, J.S.; Choi, A.; Herr, J.; Carlson, J.E. Comparative and phylogenomic analyses of cinnamoyl-CoA reductase and cinnamoyl-CoA-reductase-like gene family in land plants. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencoret, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Nieto, L.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; Faulds, C.B.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J.; Martínez, A.T.; Del Río, J.C. Lignin composition and structure in young versus adult Eucalyptus globulus plants. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, F.; Wang, L.; Zhan, Q.; Wu, P.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Cloning and expression analysis of cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) genes in sorghum. Peer J. 2016, 4, e2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, D.A.; Wang, M.; Matunis, M.J. The small ubiquitin-like modifier-1(SUMO-1)consensus sequence mediates Ubc9binding and is essential for SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21664–21669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Tang, X.; Zhang, N.; Liu, W.G.; Si, H.J. SUMO and SUMOylation in plant abiotic stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 91, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyser, H.M.O.; Lincoln, C.A.; Timpte, C.; Lammer, D.; Turner, J.; Estelle, M. Arabidopsis auxin-resistance gene AXR1 encodes a protein related to ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1. Nature 1993, 364, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, G.; Estelle, M. Regulation of cullin-based ubiquitin ligases by the Nedd8/RUB ubiquitin-like proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 15, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasiri, S.; Dharmasiri, N.; Hellmann, H.; Estelle, M. The RUB/Nedd8conjugation pathway is required for early development in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1762–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; Yi, R.; Shen, J.; Huang, S. Actin cytoskeleton in the control of vesicle transport, cytoplasmic organization, and pollen tube tip growth. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenouard, N.; Xuan, F.; Tsien, R.W. Synaptic vesicle traffic is supported by transient actin filaments and regulated by PKA and NO. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; An, Y.Q.; McDowell, J.M.; McKinney, E.C.; Meagher, R.B. The Arabidopsis ACT11 actin gene is strongly expressed in tissues of the emerging inflorescence, pollen, and developing ovules. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, T.; Sugita, K.; Ahamed Rahman, A.; Rahman, A. Actin isovariant ACT7 controls root meristem development in Arabidopsis through modulating auxin and ethylene responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 6255–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Lan, T.; Mo, B.X. Extraribosomal functions of cytosolic ribosomal proteins in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 607157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Xiong, L.M.; Ishitani, M.; Zhu, J.K. An Arabidopsis mutation in translation elongation factor 2 causes superinduction of CBF/DREB1 transcription factor genes but blocks the induction of their downstream targets under low temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7786–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.Y.; Park, S.W.; Chung, Y.S.; Chung, C.H.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, J.H. Molecular cloning of low-temperature-inducible ribosomal proteins from soybean. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1153–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studt-Reinhold, L.; Atanasoff-Kardjalieff, A.K.; Berger, H.; Petersen, C.; Bachleitner, S.; Sulyok, M.; Fischle, A.; Humpf, H.U.; Kalinina, S.; Søndergaard, T.E. H3K27me3 is vital for fungal development and secondary metabolite gene silencing, and substitutes for the loss of H3K9me3in the plant pathogen Fusarium proliferatum. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chujo, T.; Scott, B. Histone H3K9 and H3K27 methylation regulates fungal alkaloid biosynthesis in a fungal endophyte-plant symbiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Lu, L.; Bian, X.H.; Li, Q.T.; Han, J.Q.; Tao, J.J.; Yin, C.C.; Lai, Y.C.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.D.; et al. Zinc-finger protein GmZF351 improves both salt and drought stress tolerance in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1636–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, F.; Xing, J.; Zhang, K.; Dong, J. Identification and ex-pression analysis of maize histone-coding genes. J. Hebei Agric. Univ. 2022, 45, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.H.; Wu, H.M.; Zhou, Z.M.; Lin, Y.J. Introduction of citrate synthase gene (CS) into an elite indica rice restorer line minghui 86 by Agrobacterium-mediated method. Mol. Plant Breed. 2006, 4, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.C.; Yao, X.H.; Wang, K.L.; Lin, P.; Gong, H.E.; Zhuo, R.Y. Cloning and expression analysis of citrate synthase (CS) gene in Camellia oleifera. Bull. Bot. Res. 2016, 36, 556–564. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W.; Lv, B.; Wang, B.; Yang, G. Isolation and Functional Analysis of MdCS1: A Gene Encoding a Citrate Synthase in Malus Domestica (L.) Borkh. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pu, Q.; Ding, H.; Han, J.; Fan, T.; Bai, X.; Yang, G. Isolation and Functional Analysis of MxCS3: A Gene Encoding a Citrate Synthase in Malus xiaojinensis, with Functions in Tolerance to Iron Stress and Abnormal Flower in Transgenic Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 82, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, S. Transcriptomic Response of Larix kaempferi to Infection Stress from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forests 2025, 16, 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121858

Li D, Wang W, Wang Y, Wu H, Wang J, Jiang S. Transcriptomic Response of Larix kaempferi to Infection Stress from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121858

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Debin, Weitao Wang, Yijing Wang, Hao Wu, Jiaqing Wang, and Shengwei Jiang. 2025. "Transcriptomic Response of Larix kaempferi to Infection Stress from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus" Forests 16, no. 12: 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121858

APA StyleLi, D., Wang, W., Wang, Y., Wu, H., Wang, J., & Jiang, S. (2025). Transcriptomic Response of Larix kaempferi to Infection Stress from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forests, 16(12), 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121858