Landscape Aesthetics Quality in Subalpine Forests of Eastern Tibetan Plateau Will Greatly Decrease by the End of the Century?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

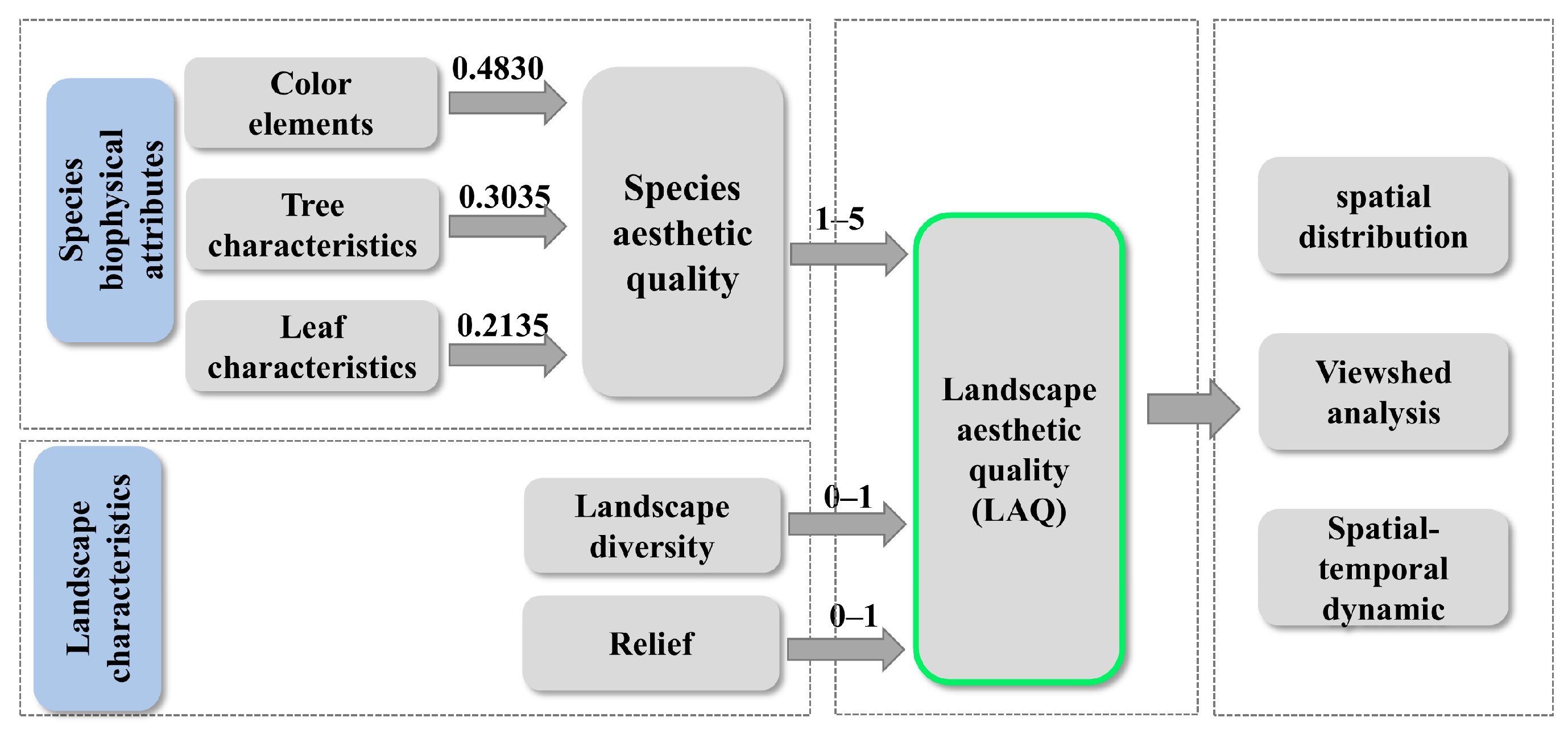

2.2. Approach Used for Assessing LAQ

2.2.1. Species Aesthetic Quality

- (a)

- Determinants and indicators

- (b)

- Data collection

- (c)

- Questionnaire survey

- (d)

- Standardized and weighted

- (e)

- Method validation

2.2.2. Landscape Aesthetic Quality

2.3. Viewshed and Spatial–Temporal Dynamic Analysis

2.4. Mann–Kendall Test for Trend Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mapped Elements for Landscape Aesthetic Quality

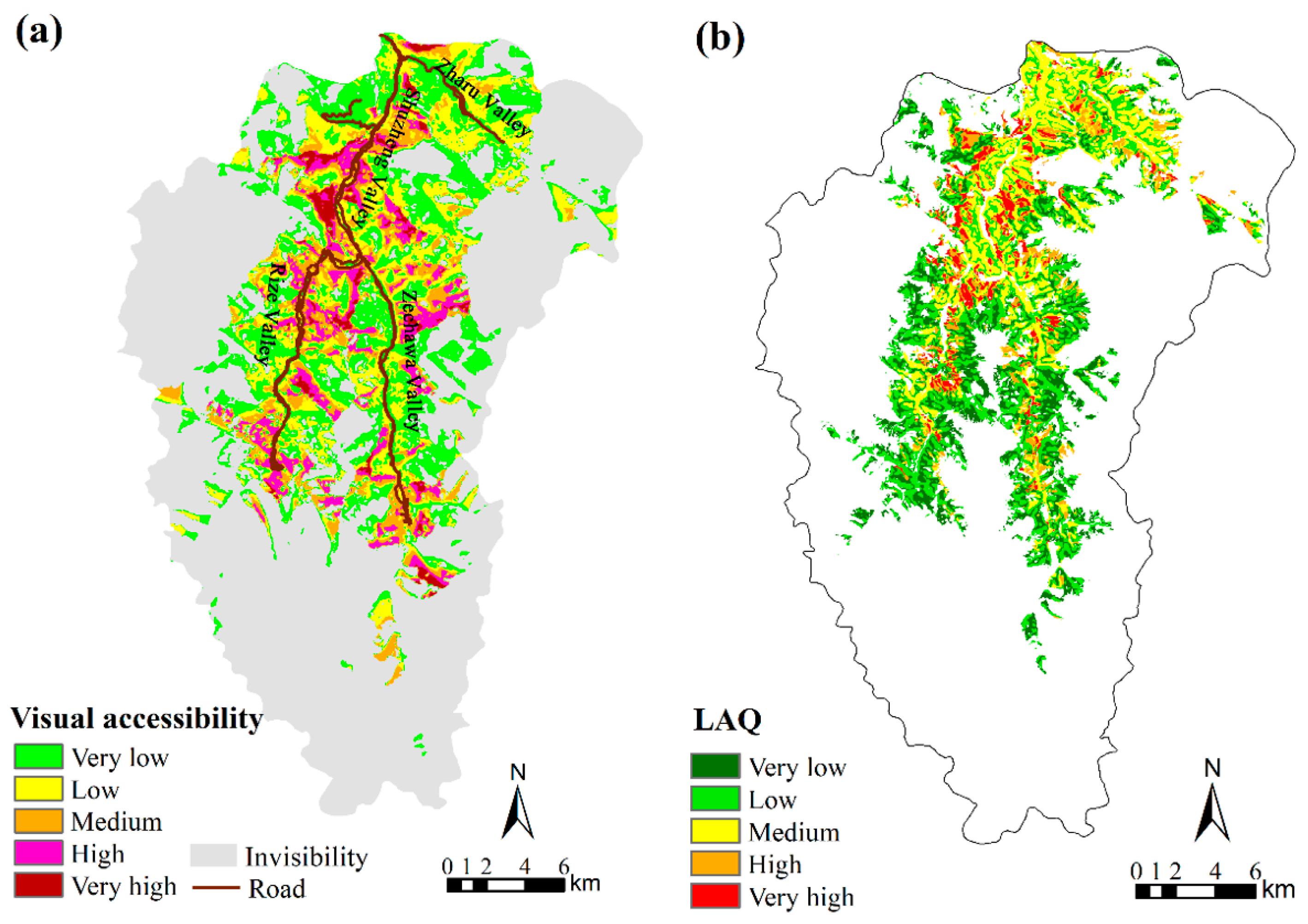

3.2. Landscape Aesthetic Quality Map

3.3. Viewshed Analysis

3.4. Spatial–Temporal Dynamic

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Insights

4.2. Aesthetic Quality Map

4.3. Implications for Management and Planning

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program) (Ed.) Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Galler, C.; Hermes, J.; Neuendorf, F.; Von Haaren, C.; Lovett, A. Applying ecosystem services indicators in landscape planning and management: The ES-in-Planning framework. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Onaindia, M.; Madariaga, I.; Verburg, P.H. Mapping recreation and aesthetic value of ecosystems in the Bilbao Metropolitan Greenbelt (northern Spain) to support landscape planning. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, T. Coordinating ecosystem service trade-offs to achieve win–win outcomes: A review of the approaches. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 82, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Shamohamadi, S.; García-Martín, M.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Shakeri, Z.; Valipour, A. Community, pastoralism, landscape: Eliciting values and human-nature connectedness of forest-related people. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 233, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xiong, K.; Zhao, X.; Lyu, X. Mapping and assessment of karst landscape aesthetic value from a world heritage perspective: A case study of the Huangguoshu Scenic area. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribot, A.-S.; Deter, J.; Mouquet, N. Integrating the aesthetic value of landscapes and biological diversity. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirpke, U.; Mölk, F.; Feilhauer, E.; Tappeiner, U.; Tappeiner, G. How suitable are discrete choice experiments based on landscape indicators for estimating landscape preferences? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerkamp, C.J.; Schipper, A.M.; Hedlund, K.; Lazarova, T.; Nordin, A.; Hanson, H.I. A review of studies assessing ecosystem services provided by urban green and blue infrastructure. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Yang, Z. Evaluation for landscape aesthetic value of the Natural World Heritage Site. Environ. Monit. Asse. 2019, 191, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Wu, X.; Pereira, P.; Esteban Lucas-Borja, M. Integrating preferences and social values for ecosystem services in local ecological management: A framework applied in Xiaojiang Basin Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 91, 104339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Hu, X. Systematic review of ecosystem services flow measurement: Main concepts, methods, applications and future directions. Ecosys. Serv. 2022, 58, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosal, A.S.; Ziv, G. Landscape aesthetics: Spatial modelling and mapping using social media images and machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Fürst, C.; Koschke, L.; Witt, A.; Makeschin, F. Assessment of landscape aesthetics—Validation of a landscape metrics-based assessment by visual estimation of the scenic beauty. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 32, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Liu, C. Towards landscape visual quality evaluation: Methodologies, technologies, and recommendations. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; Liao, L.; Kang, X.; Xu, Z.; Fu, T.; Cao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Dong, J. Cultural ecosystem services and disservices in protected areas: Hotspots and influencing factors based on tourists’ digital footprints. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 70, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Tappeiner, U. Predicting scenic beauty of mountain regions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, J.; Albert, C.; von Haaren, C. Assessing the aesthetic quality of landscapes in Germany. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskas, M.; Miksa, K.; Inacio, M.; Gomes, E.; Pereira, P. Mapping and assessment of landscape aesthetic quality in Lithuania. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Caruana, J.; Zammit, A. Assessing the capacity and flow of ecosystem services in multifunctional landscapes: Evidence of a rural-urban gradient in a Mediterranean small island state. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Tao, J. Canopy Gaps Improve Landscape Aesthetic Service by Promoting Autumn Color-Leaved Tree Species Diversity and Color-Leaved Patch Properties in Subalpine Forests of Southwestern China. Forests 2021, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Soliveres, S.; Penone, C.; Manning, P.; van der Plas, F.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Ammer, C.; Schall, P.; Gossner, M.M.; et al. Multiple forest attributes underpin the supply of multiple ecosystem services. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, R.A.; Pearson, S.M.; Turner, M.G. Landscape dynamics of floral resources affect the supply of a biodiversity-dependent cultural ecosystem service. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Wang, Y.; Hao, S.; Xu, W.; Lv, L.; Yu, S. Spatial-temporal variation and tradeoffs/synergies analysis on multiple ecosystem services: A case study in the Three-River Headwaters region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 116, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Qiao, X.; Jiang, M.; Li, Q.; Gu, Z.; Liu, F. Forest dynamics and carbon storage under climate change in a subtropical mountainous region in central China. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, T.; Xie, P.; Chen, H.; Su, Z. Temporal Changes in Community Structure over a 5-Year Successional Stage in a Subtropical Forest. Forests 2020, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qie, G.; Wang, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, X.; Li, M. Relationship between Forest Color Characteristics and Scenic Beauty: Case Study Analyzing Pictures of Mountainous Forests at Sloped Positions in Jiuzhai Valley, China. Forests 2017, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Deng, X. Assessment of cultural ecosystem services of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: Guarding the beauty of the Plateau, co-creating a better future. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Luo, P.; Yang, H.; Luo, C.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xie, W. Exploring the Relationship between Forest Scenic Beauty with Color Index and Ecological Integrity: Case Study of Jiuzhaigou and Giant Panda National Park in Sichuan, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xu, R.; Wang, N.; Qian, J.; Tu, W.; Luo, P.; Xing, A.Z.F. Unveiling the potential supply of cultural ecosystem services on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Insights from tourist hiking trajectories. Ecosyst. Serv. 2025, 73, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zou, H.; Bachelot, B.; Dong, T.; Zhu, Z.; Liao, Y.; Plenković-Moraj, A.; Wu, Y. Predicting the responses of subalpine forest landscape dynamics to climate change on the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4352–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuper, R. Effects of Flowering, Foliation, and Autumn Colors on Preference and Restorative Potential for Designed Digital Landscape Models. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 544–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, A.; Petersson, L.; Nilsson, O.; Witzell, J.; Cleary, M.; Felton, A.M.; Björkman, C.; Sang, Å.O.; Jonsell, M.; Holmström, E.; et al. The tree species matters: Biodiversity and ecosystem service implications of replacing Scots pine production stands with Norway spruce. Ambio 2020, 49, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, A.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liang, E.; Wang, Y.; Babst, F.; Leavitt, S.W.; Camarero, J.J. Past the climate optimum: Recruitment is declining at the world’s highest juniper shrublines on the Tibetan Plateau. Ecology 2019, 100, e02557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Du, W.; Zhou, G.; Qin, L.; Sun, Z. Modelling leaf phenology of some trees with accumulated temperature in a temperate forest in northeast China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 489, 119085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, G.; Marsland, S.; Lyons, P. Computational production of colour harmony. Part 2: Experimental evaluation of a tool for gui colour scheme creation. Color Res. Appl. 2013, 38, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Lin, W.; Diao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhao, C. Implementation of the visual aesthetic quality of slope forest autumn color change into the configuration of tree species. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Han, D.; Chen, C.; Shen, X. KTMN: Knowledge-driven Two-stage Modulation Network for visual question answering. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Shi, J.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.-H.; Khan, M.K.; Li, K.-C. LRCN: Layer-residual Co-Attention Networks for visual question answering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 263, 125658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Bishop, I.D.; Bebi, P. Predicting the scenic beauty value of mapped landscape changes in a mountainous region through the use of GIS. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riitters, K.H.; O’Neill, R.V.; Hunsaker, C.T.; Wickham, J.D.; Yankee, D.H.; Timmins, S.P.; Jones, K.B.; Jackson, B.L. A factor analysis of landscape pattern and structure metrics. Landsc. Ecol. 1995, 10, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, N.; Hiura, T. Demand and supply of cultural ecosystem services: Use of geotagged photos to map the aesthetic value of landscapes in Hokkaido. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 24, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenoff, D.J. LANDIS and forest landscape models. Ecol. Model. 2004, 180, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, R.M.; Domingo, J.B.; Sturtevant, B.R.; Williams, J.S.; Rudy, A.; Gustafson, E.J.; Mladenoff, D.J. Design, development, and application of LANDIS-II, a spatial landscape simulation model with flexible temporal and spatial resolution. Ecol. Model. 2007, 201, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Zamora, R.; Hódar, J.A.; Gómez, J.M. Seedling establishment of a boreal tree species (Pinus sylvestris) at its southernmost distribution limit: Consequences of being in a marginal Mediterranean habitat. J. Ecol. 2004, 92, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, A.; Peng, C.; Zhao, S.; Ci, L. Changes in forest biomass carbon storage in China between 1949 and 1998. Science 2001, 292, 2320–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica. 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, M.M.; Wang, K.L.; Yang, N.; Li, F.; Zou, Y.A.; Chen, X.S.; Deng, Z.M.; Xie, Y.H. Evaluation and variation trends analysis of water quality in response to water regime changes in a typical river-connected lake (Dongting Lake), China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Gill, A.R.; Alsafadi, K.; Hijazi, O.; Yadav, K.K.; Hasan, M.A.; Khan, A.H.; Islam, S.; Cabral-Pinto, M.; Harsanyi, E. An overview of greenhouse gases emissions in Hungary. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, H. A rank invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Proc. R. Neth. Acad. Sci. 1950, 53, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Weyland, F.; Laterra, P. Recreation potential assessment at large spatial scales: A method based in the ecosystem services approach and landscape metrics. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 39, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio Buendia, A.V.; Perez-Albert, Y.; Serrano Gine, D. Mapping Landscape Perception: An Assessment with Public Participation Geographic Information Systems and Spatial Analysis Techniques. Land 2021, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paracchini, M.L.; Zulian, G.; Kopperoinen, L.; Maes, J.; Schägner, J.P.; Termansen, M.; Zandersen, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Scholefield, P.A.; Bidoglio, G. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A framework to assess the potential for outdoor recreation across the EU. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Ding, G. Coexistence Perspectives: Exploring the impact of landscape features on aesthetic and recreational values in urban parks. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S. Handbook of Vitreo-Retinal Disorder Management: A Practical Reference Guide; World Scientific: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.M. Color Quantization and Evaluation Research on Fall-Color Trees in Beijing; Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bossard, C.C.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Rose, A.; Tang, Y. New patterns of establishment and growth of Picea, Abies and Betula tree species in subalpine forest gaps of Jiuzhaigou National Nature Reserve, Sichuan, southwestern China in a changing environment. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 356, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, N.; Segnon, A.C.; Birhane, E. Ecosystem Service Values Changes in Response to Land-Use/Land-Cover Dynamics in Dry Afromontane Forest in Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 163, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersperger, A.M.; Bürgi, M.; Wende, W.; Bacău, S.; Grădinaru, S.R. Does landscape play a role in strategic spatial planning of European urban regions? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 194, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wu, C.; Li, N.; Wang, P.; Li, J. Visual Aesthetic Quality of Qianjiangyuan National Park Landscapes and Its Spatial Pattern Characteristics. Forests 2024, 15, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Weight | Sub-Indicator | Weight | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color elements | 0.4830 | Hue | 0.1411 | Hue was classified into three categories according to the color of eight tree species: yellow, orange and green. |

| Saturation | 0.1022 | Saturation was classified into three categories—high, medium, and low—based on the saturation ranges of eight tree species using the natural breaks method. | ||

| Brightness | 0.0984 | Brightness was classified into three categories: high brightness, medium brightness and low brightness using the natural breaks method. | ||

| Discoloration period | 0.1413 | The duration of discoloration period. | ||

| Tree characteristics | 0.3035 | Crown shape | 0.1423 | Tree species were classified into four categories according to the crown shape: ovate, wide ovate, conical and umbrella. |

| Trunk clarity | 0.0732 | Tree species were classified into three categories according to the extent of trunk clarity: high-clarity, low-clarity and unclarity. | ||

| Crown width | 0.0880 | The width of crown | ||

| Leaf characteristics | 0.2135 | Leaf shape | 0.0937 | Leaf form were classified into three categories according to the leaf form of eight tree species: ovate, obovate and striped. |

| Leaf area | 0.0588 | |||

| Leaf density | 0.0610 | We used the biomass ratio of branches and leaves to reflect the extent of dense tree canopy. |

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | CV % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species aesthetic quality | 3.03 | 2.52 | 5 | 0.68 | 22.44 |

| Landscape diversity | 0.37 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.16 | 43.24 |

| Relief | 0.7 | 0 | 1 | 0.34 | 48.57 |

| LAQ | 4.53 | 2.69 | 7 | 0.84 | 18.54 |

| LAQ (Viewshed) | 4.68 | 3.20 | 7 | 0.87 | 18.59 |

| Visual Accessibility | Landscape Aesthetic Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High | |

| Very low | 14.4 (18.2) | 26.0 (20.7) | 18.1 (31.7) | 4.80 (23.0) | 4.21 (26.9) |

| Low | 10.1 (12.8) | 17.8 (14.2) | 13.8 (24.3) | 4.45 (21.3) | 3.66 (23.4) |

| Medium | 6.64 (8.39) | 10.2 (8.11) | 6.16 (10.8) | 2.15 (10.3) | 1.93 (12.4) |

| High | 3.78 (4.78) | 6.58 (5.25) | 4.61 (8.05) | 1.82 (8.70) | 1.01 (6.45) |

| Very high | 0.38 (0.47) | 1.78 (1.42) | 2.34 (4.10) | 0.50 (2.41) | 0.58 (3.70) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, C.; Bachelot, B.; Yang, Y.; Dong, T.; Wu, Y. Landscape Aesthetics Quality in Subalpine Forests of Eastern Tibetan Plateau Will Greatly Decrease by the End of the Century? Forests 2025, 16, 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121804

Liu J, Du J, Zhang C, Bachelot B, Yang Y, Dong T, Wu Y. Landscape Aesthetics Quality in Subalpine Forests of Eastern Tibetan Plateau Will Greatly Decrease by the End of the Century? Forests. 2025; 16(12):1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121804

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Junyan, Jie Du, Chenfeng Zhang, Benedicte Bachelot, Yiling Yang, Tingfa Dong, and Yan Wu. 2025. "Landscape Aesthetics Quality in Subalpine Forests of Eastern Tibetan Plateau Will Greatly Decrease by the End of the Century?" Forests 16, no. 12: 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121804

APA StyleLiu, J., Du, J., Zhang, C., Bachelot, B., Yang, Y., Dong, T., & Wu, Y. (2025). Landscape Aesthetics Quality in Subalpine Forests of Eastern Tibetan Plateau Will Greatly Decrease by the End of the Century? Forests, 16(12), 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121804