Response of Eucalyptus Seedlings to Water Stress in a Warm Tropical Region in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

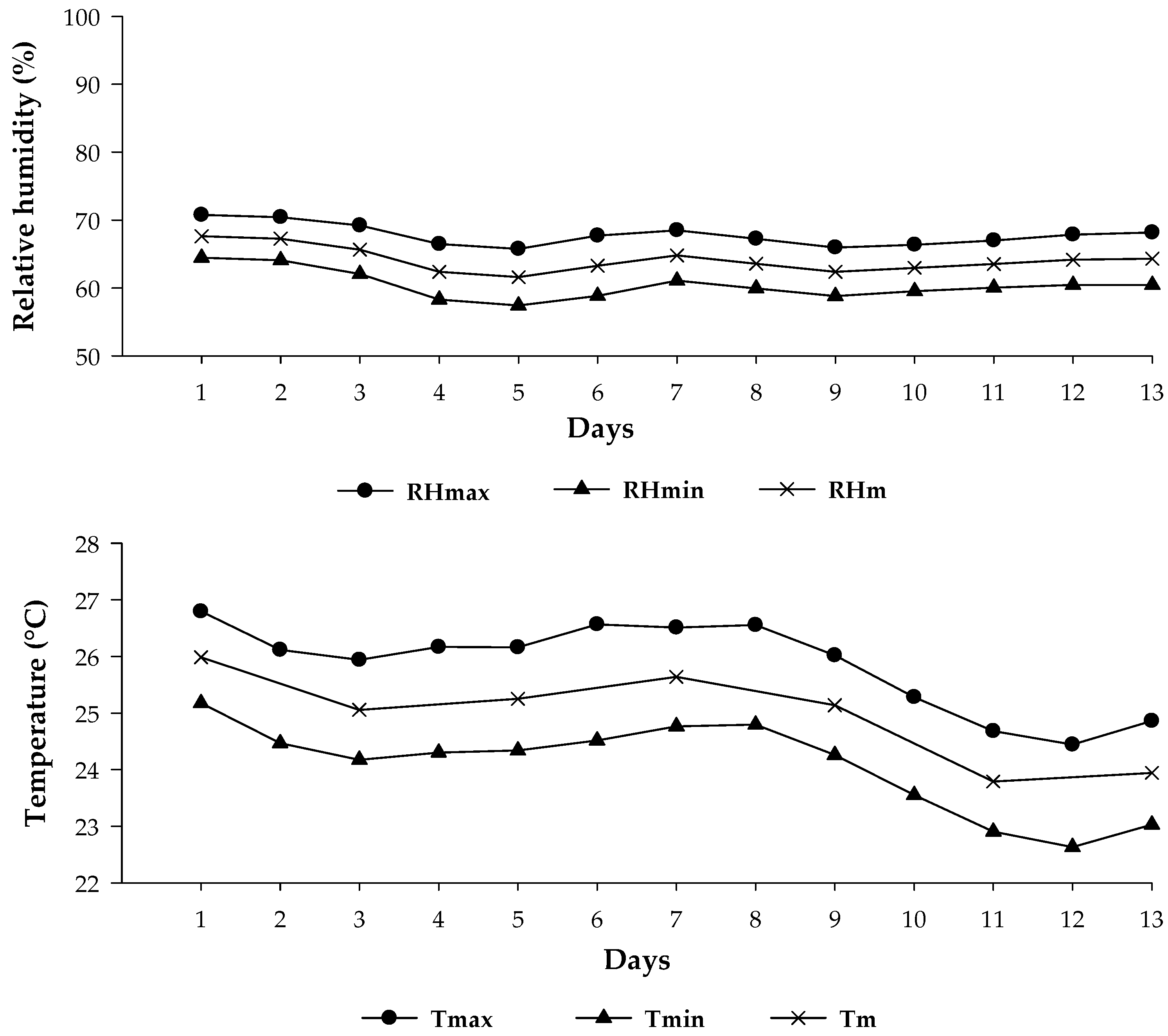

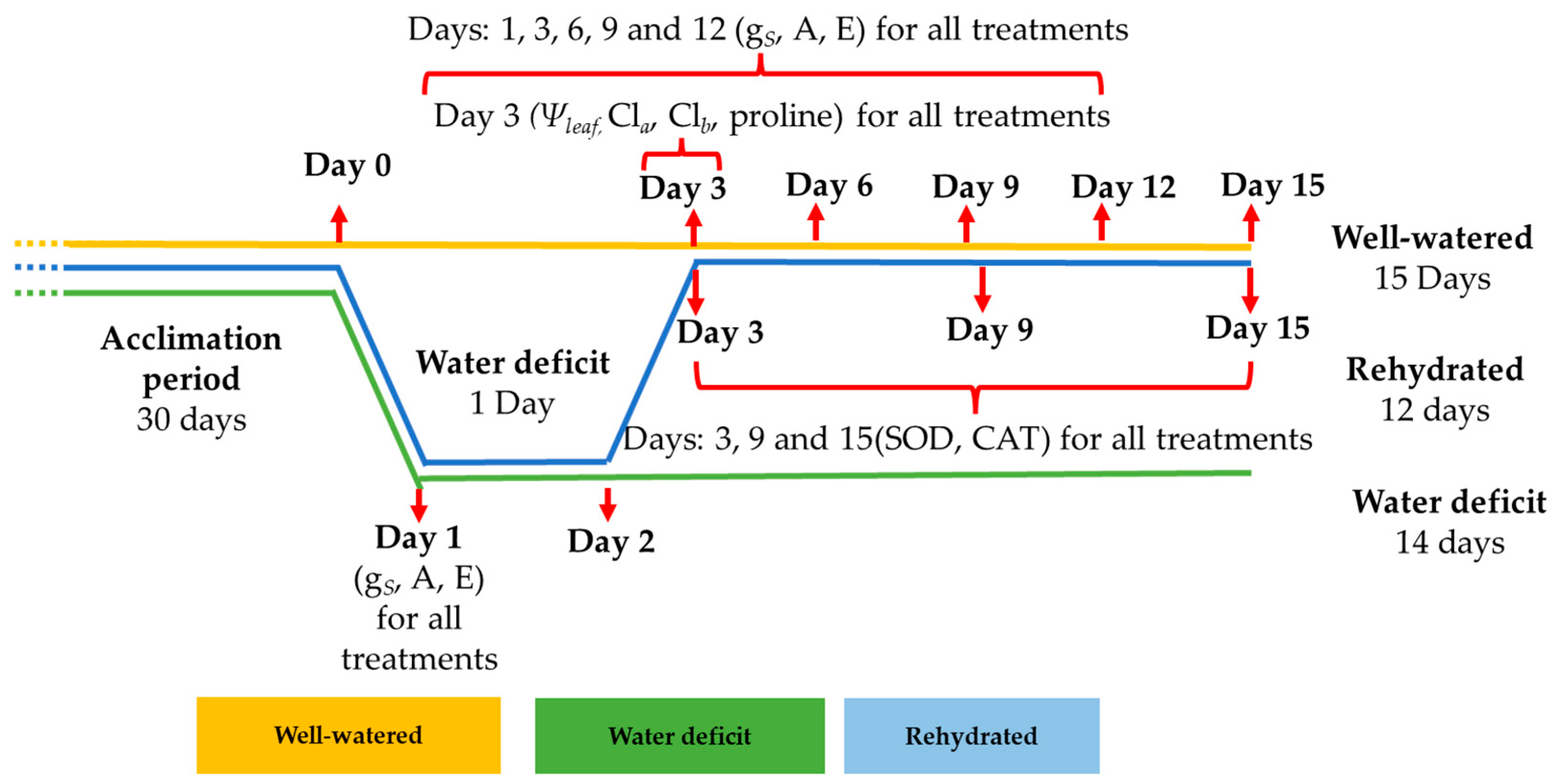

2. Materials and Methods

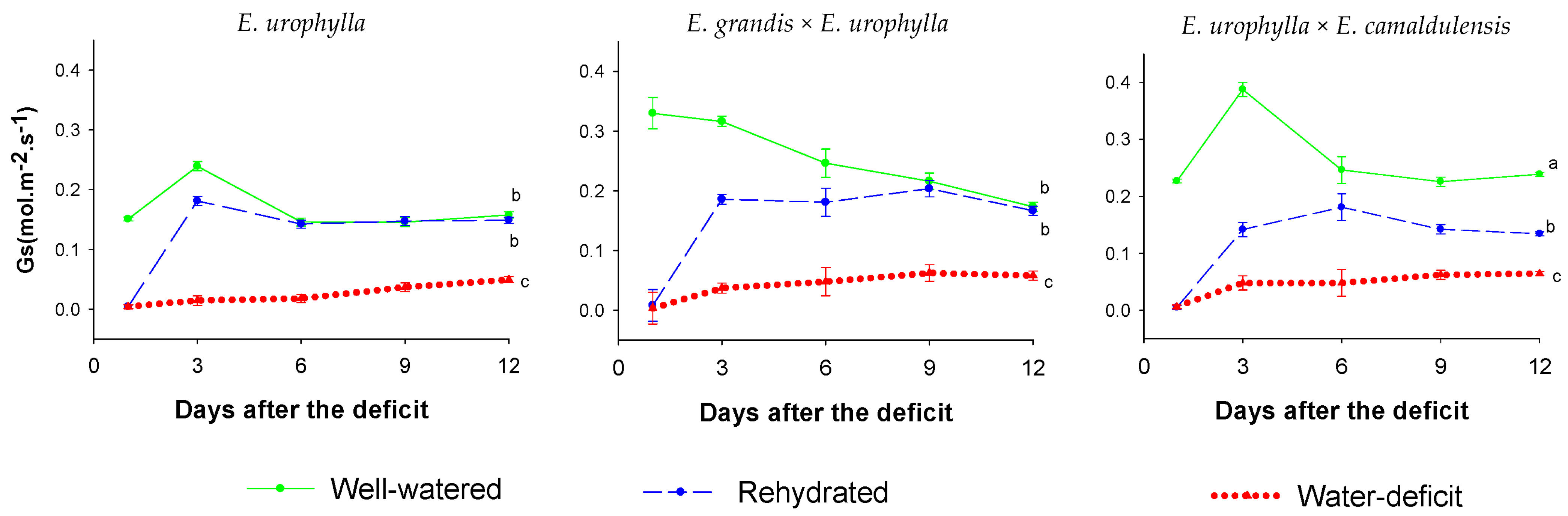

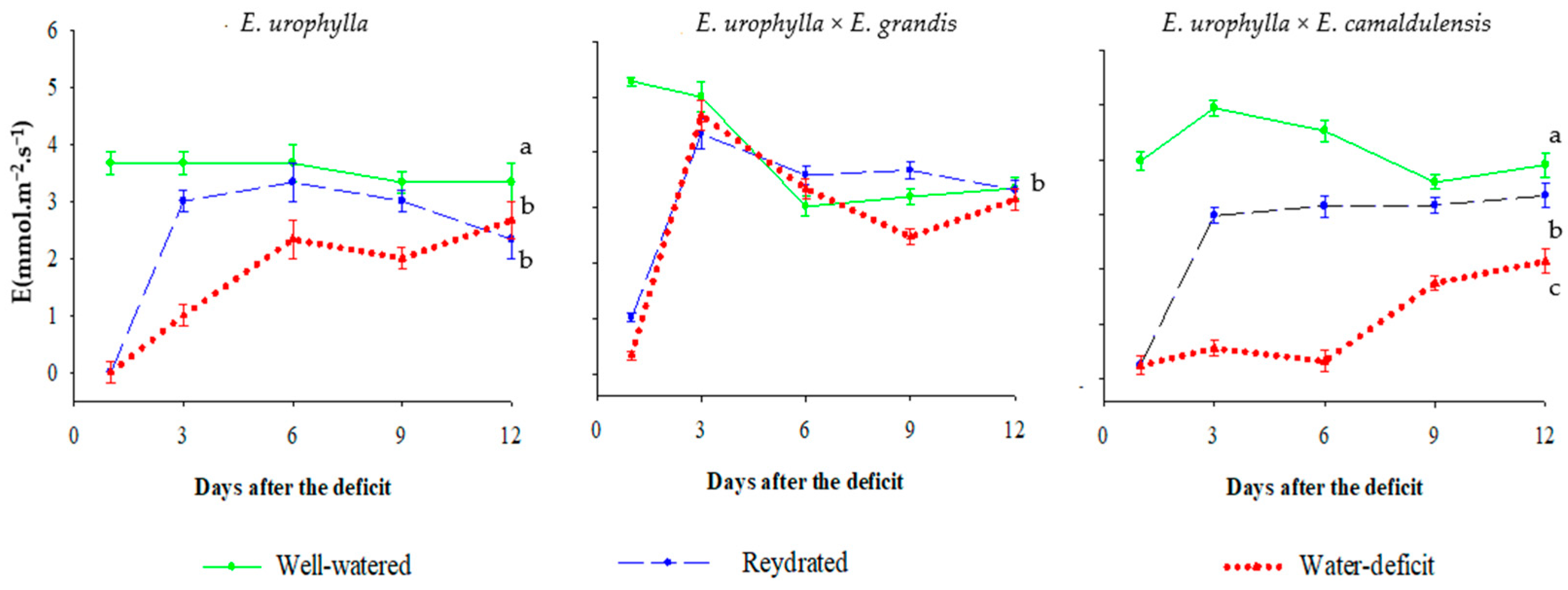

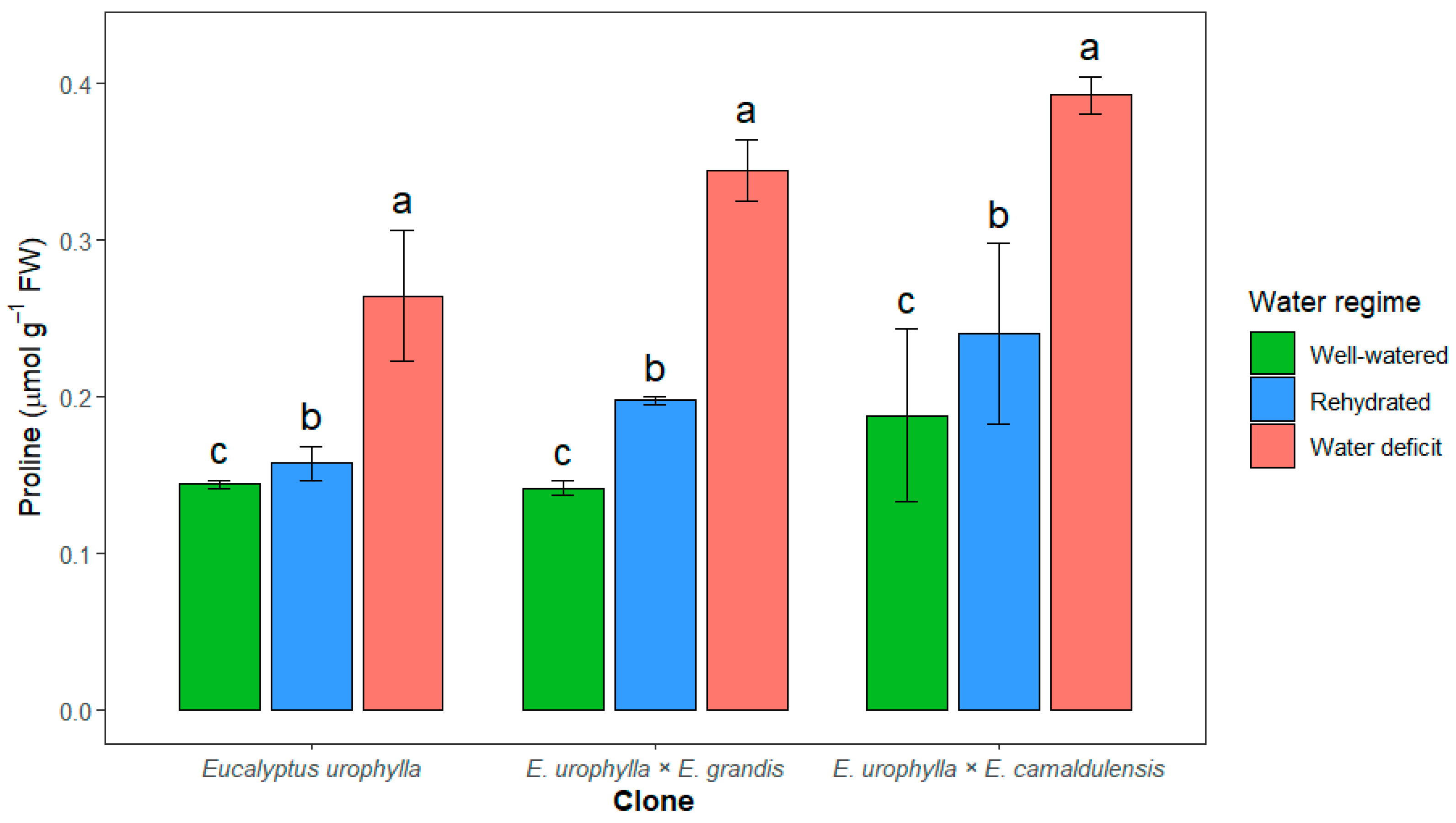

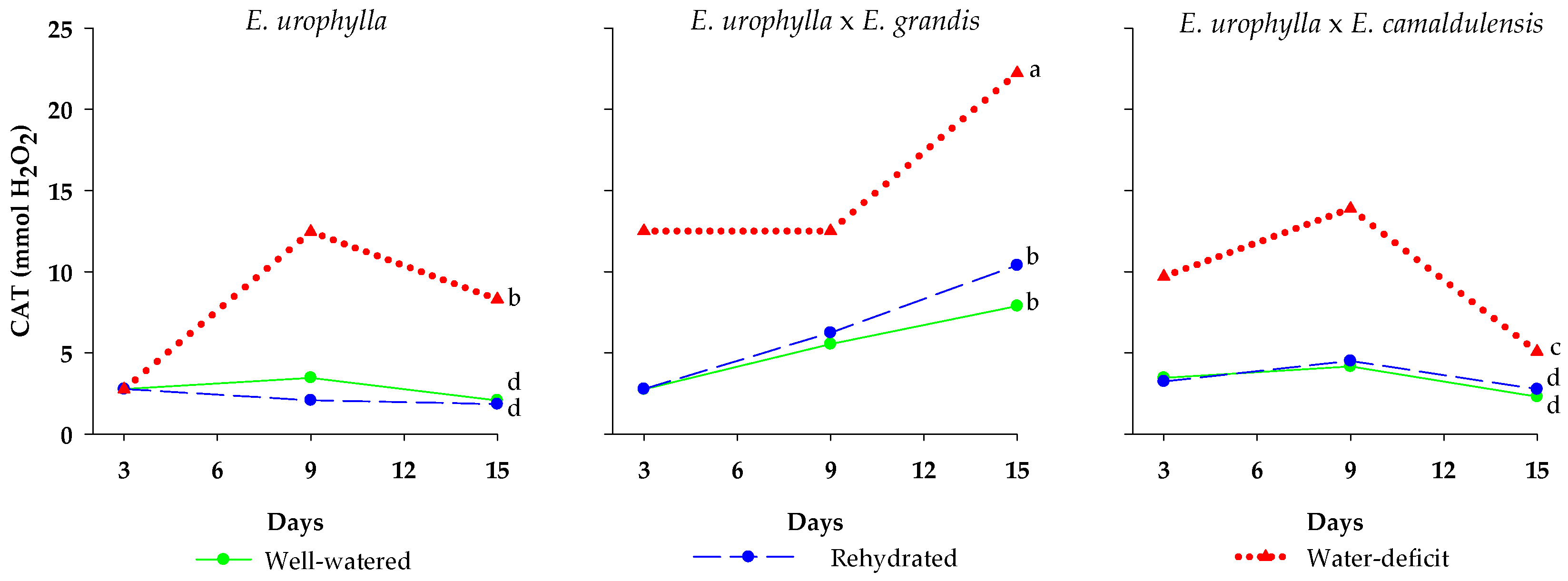

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022: Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Economies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian Tree Industry—IBÁ. Brazilian Tree Industry Report; Brazilian Tree Industry: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian Forest Service—SFB. Produção da Extração Vegetal e Silvicultura. Available online: https://publicacoes-snif.florestal.gov.br/florestasdobrasil/pt/producao-economia-e-mercado-florestal/producao-e-extracao-vegetal/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Brazilian Tree Industry—IBÁ. Brazilian Tree Industry Report; Brazilian Tree Industry: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian Tree Industry—IBÁ. Brazilian Tree Industry Report; Brazilian Tree Industry: Brasília, Brazil, 2016; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, L.F.; Cassalho, F.; Viola, M.R.; Beskow, S.; Coelho, G.; da Silva Nardes, K. Spatial distribution of climatic variables in Tocantins State, Brazil. Científica 2019, 47, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Candido, H.G.; Corrêa, G.R.; Campos, P.V.; Senra, E.O.; Gjorup, D.F.; Fernandes Filho, E.I. Soils of Campos Rupestres (Rupestrian Grasslands) of the Old Brazilian Mountain Ranges. In The Soils of Brazil; World Soils Book Series; Schaefer, C.E.G.R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerayer, A. Guia do Eucalipto—Oportunidades Para um Desenvolvimento Sustentável; Conselho de Informações Sobre Biotecnologia: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Alvares, C.A.; Rocha, J.H.T.; Brandani, C.B.; Hakamada, R. Eucalypt plantation management in regions with water stress. South. For. J. For. Sci. 2017, 2017, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Rasheed, R.; Hussain, I.; Riaz, M.; Arif, M.S. Environmental stress and secondary metabolites in plants: An overview. Plant Metab. Regul. Under Environ. Stress 2018, 2018, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaille, M.; Fabre, N.; Clément, C.; Ait Barka, E. Advances in Wheat Physiology in Response to Drought and the Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria to Trigger Drought Tolerance. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osakabe, Y.; Kajita, S.; Osakabe, K. Genetic engineering of woody plants: Current and future targets in a stressful environment. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 142, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Leyva-Gonzalez, M.A.; Ha, C.V.; Fujita, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; et al. Arabidopsis AHP2, AHP3, and AHP5 histidine phosphotransfer proteins function as redundant negative regulators of drought stress response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4840–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.V.; Leyva-Gonzalez, M.A.; Osakabe, Y.; Tran, U.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Dong, N.V.; et al. Positive regulatory role of strigolactone in plant responses to drought and salt stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, D.; Campoe, O.C.; Alvares, C.; Carneiro, R.L.; Cegatta, Í.; Stape, J.L. The interactions of climate, spacing and genetics on clonal Eucalyptus plantations across Brazil and Uruguay. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 405, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, D.; Campoe, O.C.; Alvares, C.A.; Carneiro, R.L.; Stape, J.L. Variation in whole-rotation yield among Eucalyptus genotypes in response to water and heat stresses: The TECHS project. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 462, 117953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Zhou, M.; Shabala, S. How Does Stomatal Density and Residual Transpiration Contribute to Osmotic Stress Tolerance? Plants 2023, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti Junior, L.F.; de Araujo, M.J.; de Paula, R.C.; Queiroz, T.B.; Hakamada, R.E.; Hubbard, R.M. Quantifying turgor loss point and leaf water potential across contrasting Eucalyptus clones and sites within the TECHS research platform. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 475, 118454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Osmotic adjustment is a prime drought stress adaptive engine in support of plant production. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxa, M.; Liebthal, M.; Telman, W.; Chibani, K.; Dietz, K.J. The role of the plant antioxidant system in drought tolerance. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Blackman, C.J.; Peters, J.M.R.; Choat, B.; Rymer, P.D.; Medlyn, B.E.; Tissue, D.T. More than iso/anisohydry: Hydroscapes integrate plant water use and drought tolerance traits in 10 eucalypt species from contrasting climates. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, D.R.M.; Alvares, C.A.; Campoe, O.C.; Hakamada, R.E.; Guerrini, I.A.; Cegatta, Í.R.; Stape, J.L. Multisite evaluation of the 3-PG model for the highest phenotypic plasticity Eucalyptus clone in Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 462, 117989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Fertility Commission of the State of Minas Gerais. Recommendations for the Use of Lime and Fertilizers in Minas Gerais—5th Approximation; Ribeiro, A.C., Guimarães, P.T.G., Alvarez, V.H.V., Eds.; University of the Fraser Valley: Abbotsford, BC, Canada, 1999; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, C.C.; Oliveira, F.A.; Silva, I.F.; Amorim Neto, M.S. Evaluation of methods of available water determinaton and irrigation management in “terra roxa” under cotton crop. Braz. J. Agric. Environ. Eng. 2000, 4, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholander, P.F.; Bradstreet, E.D.; Hemmingsen, E.A.; Hammel, H.T. Sap Pressure in Vascular Plants: Negative hydrostatic pressure can be measured in plants. Science 1965, 148, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. PlantSoil Dordr. 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havir, E.A.; Mchale, N.A. Biochemical and developmental characterization of multiple forms of catalase in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.F. Sisvar: A computer statistical analysis system. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2011, 35, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.H.; Tarin, T.; Santini, N.S.; McAdam, S.A.; Ruman, R.; Eamus, D. Differences in osmotic adjustment, foliar abscisic acid dynamics, and stomatal regulation between an isohydric and anisohydric woody angiosperm during drought. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 3122–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choat, B.; Brodribb, T.J.; Brodersen, C.R.; Duursma, R.A.; López, R.; Medlyn, B.E. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 2018, 528, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, T.J.; Cochard, H. Hydraulic failure defines the recovery and point of death in water-stressed conifers. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souden, S.; Ennajeh, M.; Ouledali, S.; Massoudi, N.; Cochard, H.; Khemira, H. Water relations, photosynthesis, xylem embolism and accumulation of carbohydrates and cyclitols in two Eucalyptus species (E. camaldulensis and E. torquata) subjected to dehydration–rehydration cycle. Trees 2020, 34, 1439–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensforth, L.J.; Thorburn, P.J.; Tyerman, S.D.; Walker, G.R. Sources of water used by riparian Eucalyptus camaldulensis overlying highly saline groundwater. Oecologia 1994, 100, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, P.A.; McDonald, M.W.; Bell, J.C. Congruence between environmental parameters, morphology and genetic structure in Australia’s most widely distributed eucalypt, Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Tree Genet. Genomes 2009, 5, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholz, H.L.; Ewel, K.C.; Teskey, R.O. Water and forest productivity. For. Ecol. Manag. Amst. 1990, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Pearcy, R.W. Interactions between water stress, sun-shade acclimation, heat tolerance and photoinhibition in the sclerophyll Heteromeles arbutifolia. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Govindjee. Photosynthetic responses of sun- and shade-grown barley leaves to high light: Is the lower PSII activity in shade leaves associated with photoprotection? Photosynthetica 2014, 55, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, U.; Robredo, A.; Lacuesta, M.; Sgherri, C.; Muñoz-Rueda, A.; Navari-Izzo, F.; Mena-Petite, A. The oxidative stress caused by salinity in two barley cultivars is mitigated by elevated CO2. Physiologia Plantarum. 2009, 135, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Schansker, G.; Brestic, M.; Bussotti, F.; Calatayud, A.; Ferroni, L.; Goltsev, V.; Guidi, L.; Jajoo, A.; Misra, A.N. Frequently asked questions about chlorophyll fluorescence, the sequel. Photosynth. Res. 2017, 132, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Anjum, S.A.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y. Alteration in yield, gas exchange and chlorophyll synthesis of ramie to progressive drought stress. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, N.R.; Scalon, S.P.Q.; Novelino, J.O. Initial growth of wood iron (Caesalpinia ferrea Mart. ex. Tul var. leiostachya Benth) under different hydric regimes. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2010, 34, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.L.; Anjum, S.A.; Wang, L.C.; Saleem, M.F.; Liu, X.J.; Ijaz, M.F.; Bilal, M.F. Influence of straw mulch on yield, chlorophyll contents, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activities of soybean under drought stress. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, H.S.J.; Paula, N.F.E.; Scarpinatti, A.; Paula, R.C. Physiological responses of Eucalyptus grandis × E. urophylla genotypes to water availability and potassium fertilization. Cerne 2013, 19, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.M.A.; Souza, M.W.R.; Rodrigues, A.C.P.; Correia, L.P.S.; Veloso, R.V.S.; Santos, J.B.; Titon, M.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Laia, M.L. Determination of parameters for selection of Eucalyptus clones tolerant to drought. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 3940–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant Drought Stress: Effects, Mechanisms and Management. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 29, pp. 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, B.; Pintó-Marijuan, M.; Neves, L.; Brossa, R.; Dias, M.C.; Costa, A.; Castro, B.B.; Araújo, C.; Santos, C.; Chaves, M.M.; et al. Water stress and recovery in the performance of two Eucalyptus globulus clones: Physiological and biochemical profiles. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 150, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anami, S.; de Block, M.; Machuka, J.; Van Lijsebettnens, M. Molecular Improvement of Tropical Maize for Drought Stress Tolerance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2009, 28, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Crop responses to drought and the interpretation of adaptation. Plant Growth Regul. 1996, 20, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Chapin, F.S.; Pons, T.L. Plant Physiological Ecology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; p. 540. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, D.B.; Silva, E.C.; Santos, H.R.B.; Pacheco, C.M.; Musser, R.S.; Nogueira, R.J.M.C. Physiological and biochemical responses to drought stress in Barbados cherry. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 24, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinasabapathi, B. Metabolic engineering for stress tolerance: Installing osmoprotectant synthesis pathways. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramorski, A. Gaylussacia brasiliensis (Spreng) Meisn. (Ericaceae): Gaylussacia brasiliensis (Spreng) Meisn. (Ericaceae): Chemical Characterization and In Vitro and In Vivo Biological Activity of the Fruit. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2011; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, F.S.; Oliveira, P.R.C.; Gil, J.L.R.A.; Sousa, P.V.; Gonçalves, G.A.; Sousa, M.P.B.L.; Silveira, P.S.; Silva, L.M. Eucalyptus urocan drought tolerance mechanisms. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.M.L.C.; Deuner, S.; Oliveira, P.V.; Teixeira, S.B.; Sousa, C.P.; Bacarin, M.A.; Moraes, D.M. Antioxidant activity and the viability of sunflower seeds after saline and water stress. Rev. Bras. De Sementes 2011, 33, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.Q. Initial Development of Irrigated Eucalyptus Plants in Aquidauana-MS. Master’s Thesis, State University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Brazil, 2012; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Broetto, F.; Lüttge, U.; Ratajczak, R. Influence of light intensity and salt-treatment on mode of photosynthesis and enzymes of the antioxidative response system of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Funct. Plant Biol. 2002, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbling, K.-P.; Kelly, G.J.; Fisher, K.-H.; Latzko, E. Partial purification and properties of soluble ascorbate peroxidase from pea leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 1984, 115, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandalios, J.G. Oxygen stress snd superoxide dismutases. Plant Physiol. 1993, 101, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodecker, B.E.R. Comparison of Drought Stress Responses of Tolerant and Sensitive Eucalypt Genotypes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, T.Q. Amplitude of Optimal Temperatures for Eucalyptus Clones Growth in Brazil and Uruguay. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of São Paulo, Botucatu, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/193047 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

| pH (H2O) | P (Mehlich) mg dm−3 | O.M (g kg−1) | cmolc dm−3 of Soil | V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H + Al | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | BS | CEC | (%) | |||

| 5.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.50 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.33 | 1.83 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bezerra Bandeira Milhomem, S.; Da Silva Ramos, N.; Barreira Gonçalves, F.; Hashimoto de Medeiros, G.; Fernandes, H.E.; Dotto, M.C.; Hakamada, R.E.; Siebeneichler, S.C.; Lemus Erasmo, E.A. Response of Eucalyptus Seedlings to Water Stress in a Warm Tropical Region in Brazil. Forests 2025, 16, 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121802

Bezerra Bandeira Milhomem S, Da Silva Ramos N, Barreira Gonçalves F, Hashimoto de Medeiros G, Fernandes HE, Dotto MC, Hakamada RE, Siebeneichler SC, Lemus Erasmo EA. Response of Eucalyptus Seedlings to Water Stress in a Warm Tropical Region in Brazil. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121802

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezerra Bandeira Milhomem, Sara, Nadia Da Silva Ramos, Flavia Barreira Gonçalves, Gessica Hashimoto de Medeiros, Hallefy Elias Fernandes, Marciane Cristina Dotto, Rodrigo Eiji Hakamada, Susana Cristine Siebeneichler, and Eduardo Andrea Lemus Erasmo. 2025. "Response of Eucalyptus Seedlings to Water Stress in a Warm Tropical Region in Brazil" Forests 16, no. 12: 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121802

APA StyleBezerra Bandeira Milhomem, S., Da Silva Ramos, N., Barreira Gonçalves, F., Hashimoto de Medeiros, G., Fernandes, H. E., Dotto, M. C., Hakamada, R. E., Siebeneichler, S. C., & Lemus Erasmo, E. A. (2025). Response of Eucalyptus Seedlings to Water Stress in a Warm Tropical Region in Brazil. Forests, 16(12), 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121802