Tree-Ring Proxies for Forest Productivity Reconstruction: Advances and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

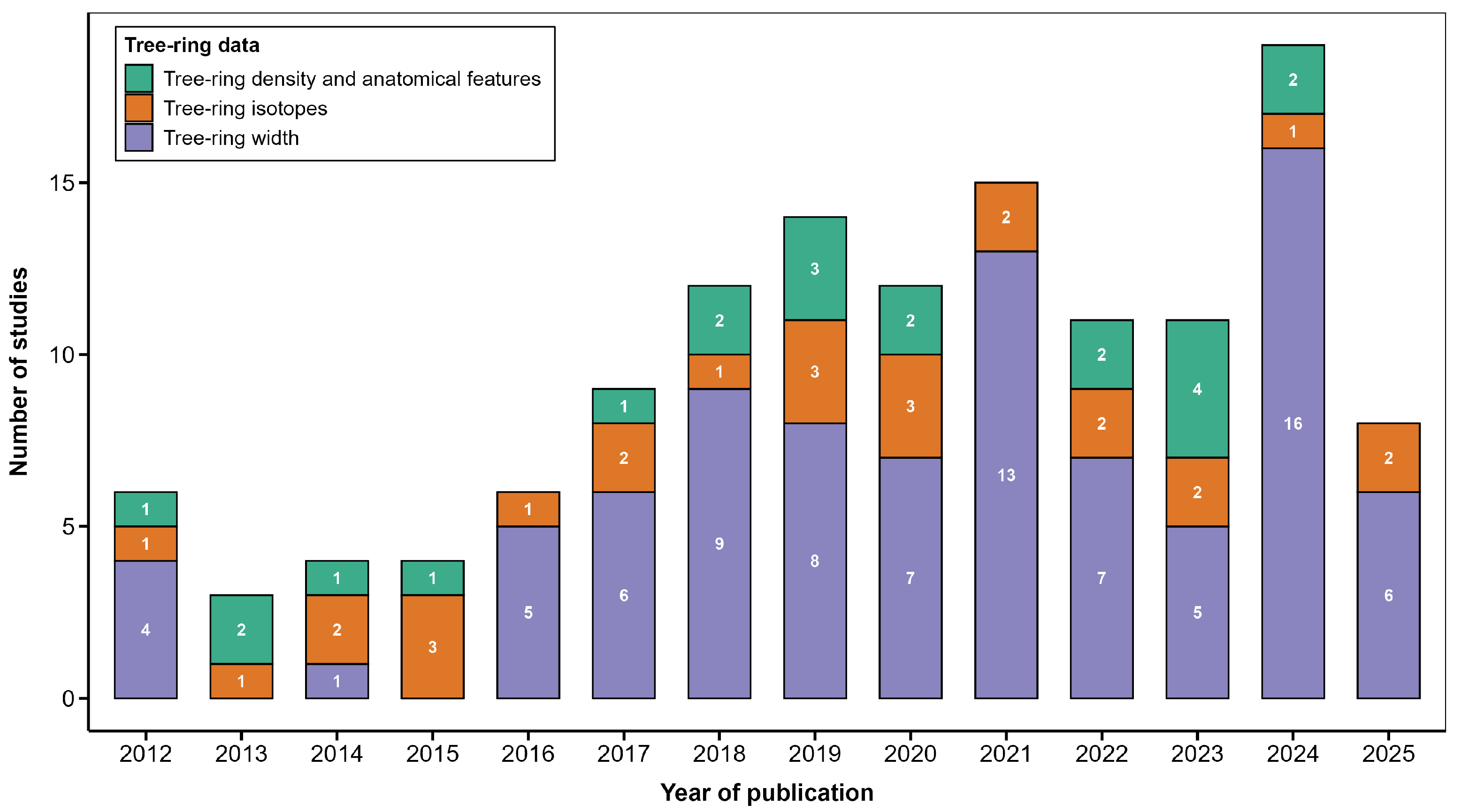

2. Research on the Relationship Between Tree-Ring Data and Forest Productivity

2.1. Tree-Ring Width

2.1.1. Relationship Between Tree-Ring Width and Forest Productivity

2.1.2. Reconstruction of Forest Productivity Using Tree-Ring Width

2.2. Tree-Ring Stable Isotopes

2.2.1. Relationship Between Tree-Ring Stable Isotopes and Forest Productivity

2.2.2. Reconstruction of Forest Productivity Using Stable Isotopes

2.3. Tree-Ring Density and Anatomical Features

3. Factors Affecting the Stability of the Relationship Between Tree-Ring Data and Forest Productivity

3.1. Climatic Factors

3.2. Topographic Factors

3.3. Atmospheric CO2 Concentration

4. Challenges and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frank, D.; Reichstein, M.; Bahn, M.; Thonicke, K.; Frank, D.; Mahecha, M.D.; Smith, P.; Van Der Velde, M.; Vicca, S.; Babst, F.; et al. Effects of Climate Extremes on the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle: Concepts, Processes and Potential Future Impacts. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2861–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Liu, Q.; Lian, X.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Wu, X. The Impacts of Climate Extremes on the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle: A Review. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.W.; Page, A.M.; Wood, S.; Fargione, J.; Masuda, Y.J.; Carrasco Denney, V.; Moore, C.; Kroeger, T.; Griscom, B.; Sanderman, J.; et al. The Principles of Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, H.C.; Phillips, O.L. The Global Relationship between Forest Productivity and Biomass. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulden, M.L.; Mcmillan, A.M.S.; Winston, G.C.; Rocha, A.V.; Manies, K.L.; Harden, J.W.; Bond-Lamberty, B.P. Patterns of NPP, GPP, Respiration, and NEP during Boreal Forest Succession. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babst, F.; Alexander, M.R.; Szejner, P.; Bouriaud, O.; Klesse, S.; Roden, J.; Ciais, P.; Poulter, B.; Frank, D.; Moore, D.J.P.; et al. A Tree-Ring Perspective on the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle. Oecologia 2014, 176, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Shen, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Net Primary Productivity (NPP) Dynamics and Associated Urbanization Driving Forces in Metropolitan Areas: A Case Study in Beijing City, China. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Harde, S.; Rajasekaran, E.; Deb Burman, P.K. Gross Primary Productivity of Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Review of Observations, Remote Sensing, and Modelling Studies over South Asia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 8461–8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Productivity and Carbon Sink Capacity of Eucalyptus Plantations in China from 1973 to 2018. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2023, 59, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni, D.; Schmid, H.P.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Loescher, H.W. Uncertainty of Annual Net Ecosystem Productivity Estimated Using Eddy Covariance Flux Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2007, 112, 2006JD008149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wu, X.; Tao, Y.; Li, M.; Qian, C.; Liao, L.; Fu, W. Review of Remote Sensing-Based Methods for Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Forests 2023, 14, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, W.; Ju, W.; Tagesson, T.; He, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Yuan, S.; et al. Modeling China’s Terrestrial Ecosystem Gross Primary Productivity with BEPS Model: Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Model Calibration. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 343, 109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dong, Q.; Pan, Y.; Yang, F.; He, M.; Huang, X.; Xu, J. Spatiotemporal Variations and Driving Forces of Regional-Scale NPP Based on a Multi-Method Integration: A Case Study in the Beibu Gulf Economic Zone. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 174, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Pang, Y.; Kong, D. Integrating Remote Sensing and 3-PG Model to Simulate the Biomass and Carbon Stock of Larix olgensis Plantation. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Bie, Q. Global-Scale Improvement of Terrestrial Gross Primary Productivity Estimation by Integrating Optical Remote Sensing with Meteorological Data. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahle, D.W.; Fye, F.K.; Cook, E.R.; Griffin, R.D. Tree-Ring Reconstructed Megadroughts over North America since A.D. 1300. Clim. Change 2007, 83, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Qin, C.; Bräuning, A.; Osborn, T.J.; Trouet, V.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; Esper, J.; Schneider, L.; Grießinger, J.; Büntgen, U.; et al. Long-Term Decrease in Asian Monsoon Rainfall and Abrupt Climate Change Events over the Past 6,700 Years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102007118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Pan, L.; Shi, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K. Radial Growth of Mongolian Pine and its Response to Climate at Different Competition Intensities. J. Ecol. 2019, 38, 1962–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Huang, J.-G.; Ma, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, P.; Yu, B.; et al. Contributions of Competition and Climate on Radial Growth of Pinus massoniana in Subtropics of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 274, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, X.; Keenan, T.F.; Piao, S. Drought Timing Influences the Legacy of Tree Growth Recovery. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3546–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, X.J.; Mack, M.C.; Johnstone, J.F. Stable Carbon Isotope Analysis Reveals Widespread Drought Stress in Boreal Black Spruce Forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3102–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.F.; Buras, A.; Gregor, K.; Layritz, L.S.; Principe, A.; Kreyling, J.; Rammig, A.; Zang, C.S. Frost Matters: Incorporating Late-Spring Frost into a Dynamic Vegetation Model Regulates Regional Productivity Dynamics in European Beech Forests. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payette, S.; Delwaide, A.; Simard, M. Frost-ring Chronologies as Dendroclimatic Proxies of Boreal Environments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, 2009GL041849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerano-Paredes, J.; Iniguez, J.M.; González-Castañeda, J.L.; Cervantes-Martínez, R.; Cambrón-Sandoval, V.H.; Esquivel-Arriaga, G.; Nájera-Luna, J.A. Increasing the Risk of Severe Wildfires in San Dimas, Durango, Mexico Caused by Fire Suppression in the Last 60 Years. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 940302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozák, M.; Šilhán, K. Comprehensive Landslide Analysis Using a Tree-Ring-Based Approach. Landslides 2024, 21, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, M.; Trappmann, D.G.; Coullie, M.I.; Ballesteros Cánovas, J.A.; Corona, C. Rockfall from an Increasingly Unstable Mountain Slope Driven by Climate Warming. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Shah, S.K.; Pandey, U.; Deeksha; Thomte, L.; Rahman, T.W.; Mehrotra, N.; Singh, D.S.; Kotlia, B.S. Vegetation Index (NDVI) Reconstruction from Western Himalaya through Dendrochronological Analysis of Cedrus deodara. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Liang, P.; An, H.; Sun, H.; Han, W.; Li, Q. Tree-Ring Widths Are Good Proxies of Annual Variation in Forest Productivity in Temperate Forests. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Bush, D.R. Carbohydrate Export from the Leaf: A Highly Regulated Process and Target to Enhance Photosynthesis and Productivity. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass Allocation to Leaves, Stems and Roots: Meta-analyses of Interspecific Variation and Environmental Control. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, T.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Jiang, S.; Guo, D.; Hou, T.; Guo, K. Evaluating the Effect of Vegetation Index Based on Multiple Tree-Ring Parameters in the Central Tianshan Mountains. Forests 2023, 14, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mašek, J.; Tumajer, J.; Lange, J.; Kaczka, R.; Fišer, P.; Treml, V. Variability in Tree-Ring Width and NDVI Responses to Climate at a Landscape Level. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiao, L.; Du, D.; Xue, R.; Wei, M.; Zhang, P. Elevation Response of Above-Ground Net Primary Productivity for Picea crassifolia to Climate Change in Qilian Mountains of Northwest China Based on Tree Rings. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Das, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Deb Burman, P.K.; Chakraborty, S. Evaluating Tree-Ring Proxies for Representing the Ecosystem Productivity in India. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2025, 69, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygalova, N.V.; Mordvin, E.Y.; Bondarovich, A.A. Productivity and Carbon Sequestration of Pinus sylvestris, L. Ribbon Forests in the Dry Steppe of Western Siberia According to Dendrochronology and MODIS Satellite Measurements. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2024, 17, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, D.; Ito, A. Temporal Changes in the Relationship between Tree-ring Growth and Net Primary Production in Northern Japan: A Novel Approach to the Estimation of Seasonal Photosynthate Allocation to the Stem. Ecol. Res. 2018, 33, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hall, F.G.; Sellers, P.J.; Marshak, A.L. The Interpretation of Spectral Vegetation Indexes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G. Is There Spatial and Temporal Variability in the Response of Plant Canopy and Trunk Growth to Climate Change in a Typical River Basin of Arid Areas. Water 2022, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rich, P.M.; Price, K.P.; Kettle, W.D. Relations between NDVI and Tree Productivity in the Central Great Plains. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Camarero, J.J.; Olano, J.M.; Martín-Hernández, N.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Gazol, A.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Bhuyan, U.; El Kenawy, A. Diverse Relationships between Forest Growth and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index at a Global Scale. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 187, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa-García, M.; Vivar-Vivar, E.D.; Sigala-Rodríguez, J.A.; Padilla-Martínez, J.R. What Are Contemporary Mexican Conifers Telling Us? A Perspective Offered from Tree Rings Linked to Climate and the NDVI along a Spatial Gradient. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, U.; Zang, C.; Vicente-Serrano, S.; Menzel, A. Exploring Relationships among Tree-Ring Growth, Climate Variability, and Seasonal Leaf Activity on Varying Timescales and Spatial Resolutions. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Hernández, A.C.; Pompa-García, M.; Martínez-Rivas, J.A.; Vivar-Vivar, E.D. Cutting the Greenness Index into 12 Monthly Slices: How Intra-Annual NDVI Dynamics Help Decipher Drought Responses in Mixed Forest Tree Species. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Fang, W.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, X.; Luo, H.; Hendrey, G.; Yi, C. Spatial Upscaling of Tree-Ring-Based Forest Response to Drought with Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Chen, F.; Zhao, X.; Hu, M.; Wang, S.; Hadad, M.A.; Roig, F.A.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H. Tree Radial Growth and Vegetation Dynamics in Northern China and Northern Patagonia Regulated by Ocean–Atmosphere Circulation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 593, 122913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, B.L.; Touchan, R.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Meko, D.M.; Sivrikaya, F. Tree Growth and Vegetation Activity at the Ecosystem-Scale in the Eastern Mediterranean. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 084008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyum, Z.G.; Ayoade, J.O.; Onilude, M.A.; Feyissa, M.T. Relationship between Space-Based Vegetation Productivity Index and Radial Growth of Main Tree Species in the Dry Afromontane Forest Remnants of Northern Ethiopia. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2019, 22, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gallardo, V.B.; Hadad, M.A.; Roig, F.A.; Gatica, G.; Chen, F. Spatio-Temporal Linkage Variations between NDVI and Tree Rings on the Leeward Side of the Northern Patagonian Andes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 553, 121593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmi, S.; Klinge, M.; Dulamsuren, C.; Schneider, F.; Hauck, M. Modelling the Productivity of Siberian Larch Forests from Landsat NDVI Time Series in Fragmented Forest Stands of the Mongolian Forest-Steppe. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shao, X. Relationships between Tree-Ring Width Index and NDVI of Grassland in Delingha. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 51, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, N.; Shao, X. Relationship between Tree Ring Indices and Vegetation Index(NDVI) in Buha River Basin, Qinghai. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2012, 34, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Brehaut, L.; Danby, R.K. Inconsistent Relationships between Annual Tree Ring-Widths and Satellite-Measured NDVI in a Mountainous Subarctic Environment. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; Gallardo-Salazar, J.L. Xylogenesis Is Uncoupled from Forest Productivity. Trees 2021, 35, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cheng, R.; Xiao, W.; Feng, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Relationship between masson pine tree-ring width and NDVI in North Subtropical Region. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 5762–5770. [Google Scholar]

- Pompa-García, M.; Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; González-Cásares, M. Inter and Intra-Annual Links between Climate, Tree Growth and NDVI: Improving the Resolution of Drought Proxies in Conifer Forests. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mašek, J.; Tumajer, J.; Lange, J.; Vejpustková, M.; Kašpar, J.; Šamonil, P.; Chuman, T.; Kolář, T.; Rybníček, M.; Jeníček, M.; et al. Shifting Climatic Responses of Tree Rings and NDVI along Environmental Gradients. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.S.; Young, D.J.N.; Latimer, A.M.; Buckley, T.N.; Magney, T.S. Importance of the Legacy Effect for Assessing Spatiotemporal Correspondence between Interannual Tree-Ring Width and Remote Sensing Products in the Sierra Nevada. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, S.; Sugimoto, A.; Kotani, A.; Ohta, T.; Morozumi, T.; Saito, S.; Hashiguchi, S.; Maximov, T. Strong and Stable Relationships between Tree-Ring Parameters and Forest-Level Carbon Fluxes in a Siberian Larch Forest. Polar Sci. 2019, 21, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannenberg, S.A.; Novick, K.A.; Alexander, M.R.; Maxwell, J.T.; Moore, D.J.P.; Phillips, R.P.; Anderegg, W.R.L. Linking Drought Legacy Effects across Scales: From Leaves to Tree Rings to Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2978–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.V.; Goulden, M.L.; Dunn, A.L.; Wofsy, S.C. On Linking Interannual Tree Ring Variability with Observations of Whole-forest CO2 Flux. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannenberg, S.A.; Schwalm, C.R.; Anderegg, W.R.L. Ghosts of the Past: How Drought Legacy Effects Shape Forest Functioning and Carbon Cycling. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, M.T.; He, Y. Temporal Connections between Long-Term Landsat Time-Series and Tree-Rings in an Urban–Rural Temperate Forest. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 103, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicca, S.; Balzarolo, M.; Filella, I.; Granier, A.; Herbst, M.; Knohl, A.; Longdoz, B.; Mund, M.; Nagy, Z.; Pintér, K.; et al. Remotely-Sensed Detection of Effects of Extreme Droughts on Gross Primary Production. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Speer, J.H.; Thapa, I. Reconstructing and Mapping Annual Net Primary Productivity (NPP) Since 1940 Using Tree Rings in Southern Indiana, U.S. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bao, A.; Xu, W.; Zheng, G.; Nzabarinda, V.; Yu, T.; Huang, X.; Long, G.; Naibi, S. Dynamics of Forest Net Primary Productivity Based on Tree Ring Reconstruction in the Tianshan Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Liang, P.; Wu, Y.; An, H.; Sun, H.; Wu, P.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.; Guo, X.; et al. A New Tree-Ring Sampling Method to Estimate Forest Productivity and Its Temporal Variation Accurately in Natural Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 433, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Hawryło, P.; Tompalski, P.; Wertz, B.; Socha, J. Linking Remotely Sensed Growth-Related Canopy Attributes to Interannual Tree-Ring Width Variations: A Species-Specific Study Using Sentinel Optical and SAR Time Series. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 221, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Martín-Hernández, N.; Camarero, J.J.; Gazol, A.; Sánchez-Salguero, R.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; El Kenawy, A.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Tomas-Burguera, M.; Gutiérrez, E.; et al. Linking Tree-Ring Growth and Satellite-Derived Gross Primary Growth in Multiple Forest Biomes. Temporal-Scale Matters. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, G.-S. Estimation of Biomass and Net Primary Productivity of Major Planted Forests in China Based on Forest Inventory Data. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 207, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babst, F.; Bouriaud, O.; Papale, D.; Gielen, B.; Janssens, I.A.; Nikinmaa, E.; Ibrom, A.; Wu, J.; Bernhofer, C.; Köstner, B.; et al. Above-ground Woody Carbon Sequestration Measured from Tree Rings Is Coherent with Net Ecosystem Productivity at Five Eddy-covariance Sites. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, A.; Barker Plotkin, A.; Bishop, D.; Pederson, N.; Poulter, B.; Hessl, A. Comparing Tree-ring and Permanent Plot Estimates of Aboveground Net Primary Production in Three Eastern U.S. Forests. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, O.; Wang, Y.; Shao, X. Advances in Study of Reconstruction of Regional Forest Net Primary Productivity based on Tree Rings. Prog. Geogr. 2014, 33, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, L. Low Net Primary Productivity of Dominant Tree Species in a Karst Forest, Southwestern China: First Evidences from Tree Ring Width and Girth Increment. Acta Geochim. 2017, 36, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Study on forest volume-to-biomass modeling and carbon storage dynamics in China. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2021, 51, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, O.; Wang, Y.; Shao, X. The Effect of Climate on the Net Primary Productivity (NPP) of Pinus koraiensis in the Changbai Mountains over the Past 50 Years. Trees 2016, 30, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, H.; Guo, Y.; Liang, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liang, E.; Ni, J. Reconstruction of above-ground biomass and net primary productivity of dominant tree species in Guizhou forests over past five decades based on tree-ring data. Acta. Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 3441–3451. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, N.M.; Kukarskih, V.V.; Galimova, A.A.; Mazepa, V.S.; Grigoriev, A.A. Climate Change Evidence in Tree Growth and Stand Productivity at the Upper Treeline Ecotone in the Polar Ural Mountains. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, G.G.; Liu, G.; Xu, S. Forest Biomass of China: An Estimate Based on the Biomass–Volume Relationship. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, Z.M. Forest Biomass Estimation at Regional and Global Levels, with Special Reference to China’s Forest Biomass. Ecol. Res. 2001, 16, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Zeng, W. Forest Carbon Storage in China Estimated Using Forestry Inventory Data. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2011, 47, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ter-Mikaelian, M.T.; Korzukhin, M.D. Biomass Equations for Sixty-Five North American Tree Species. For. Ecol. Manag. 1997, 97, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Benito, D.; Pederson, N.; Férriz, M.; Gea-Izquierdo, G. Old Forests and Old Carbon: A Case Study on the Stand Dynamics and Longevity of Aboveground Carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, B.R.; Maxwell, J.T.; Robeson, S.M.; Au, T.F. Assessing Bias in Diameter at Breast Height Estimated from Tree Rings and Its Effects on Basal Area Increment and Biomass. Dendrochronologia 2021, 67, 125844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, S.; Meng, P. Early–Latewood Carbon Isotope Enhances the Understanding of the Relationship between Tree Biomass Growth and Forest-Level Carbon Fluxes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 315, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileshi, G.W. A Critical Review of Forest Biomass Estimation Models, Common Mistakes and Corrective Measures. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 329, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Rollinson, C.R.; Babst, F.; Trouet, V.; Moore, D.J.P. Relative Influences of Multiple Sources of Uncertainty on Cumulative and Incremental Tree-Ring-Derived Aboveground Biomass Estimates. Trees 2018, 32, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Luo, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, D. Reconstruction of NDVI Based on Larix gmelinii Tree-Rings during June–September 1759–2021. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1283956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Song, H.; Sun, C.; Li, Q.; Cai, Q.; Ren, M.; Wang, L. Changes in the Tree-Ring Width-Derived Cumulative Normalized Difference Vegetation Index over Northeast China during 1825 to 2013 CE. Forests 2021, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, T.; Li, P.; Ye, Y. Reconstruction of Summer NDVI over the Past 339 Years Based on the Tree-ring Width of Picea schrenkiana in Bayinbuluke, Central Tianshan, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 3671–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Bai, H.; Hou, L.; Chen, L.; Qin, J. Reconstruction of July NDVI over 172 Years Based on Tree-ring Width of Larix chinensis in Taibai Mountain Nature Reserve, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 29, 2382–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lu, R.; Gao, S. Summer NDVI Variability Recorded by Tree Radial Growth in the Xinglong Mountain, the Eastward Extension of the Qilian Mountains, since 1845 AD. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 653–663. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, T.; An, W.; Xu, B. Reconstruction of Regional NDVI Using Tree-ring Width Chronologies in the Qilian Mountains, Northwestern China. J. Plant Ecol. 2010, 34, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, Q.; Ren, M.; Li, P. Reconstructed July to September NDVI of Past 565 Years in Baluntai region of central Tianshan Mountains based on Picea schrenkian. Quat. Sci. 2024, 44, 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X. Variation of July NDVI Recorded by Tree-ring Index of Pinus koraiensis and Abies nephrolepis Forests in the Southern Xiaoxing’an Mountains of Northeastern China. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2018, 40, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.; Eckstein, D.; Liu, H. Assessing the Recent Grassland Greening Trend in a Long-Term Context Based on Tree-Ring Analysis: A Case Study in North China. Ecol. Indic. 2009, 9, 1280–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, A.G.; Hughes, M.K.; Kirdyanov, A.V.; Losleben, M.; Shishov, V.V.; Berner, L.T.; Oltchev, A.; Vaganov, E.A. Comparing Forest Measurements from Tree Rings and a Space-Based Index of Vegetation Activity in Siberia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 035034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, A.S.; Burry, L.S.; Palacio, P.I.; Trivi, M.E.; Quesada, M.N.; Zuccarelli Freire, V.; D’Antoni, H. Ecosystems Dynamics and Environmental Management: An NDVI Reconstruction Model for El Alto-Ancasti Mountain Range (Catamarca, Argentina) from 442 AD through 1980 AD. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2024, 324, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Thapa, I.; Speer, J.H. Fine-Scale NDVI Reconstruction Back to 1906 from Tree-Rings in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Forests 2021, 12, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Matteo, G.; Nardi, P.; Fabbio, G. On the Use of Stable Carbon Isotopes to Detect the Physiological Impact of Forest Management: The Case of Mediterranean Coppice Woodland. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 389, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ren, M.; Cai, Q.; Song, H.; Ma, Y. Tree-Ring Stable Oxygen Isotope Ratio (δ18O) Records Precipitation Changes over the Past Century in the Central Part of Eastern China. Forests 2024, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.P.; Bowen, G.J.; Hemming, D.; Kahmen, A.; Knohl, A.; Lai, C.; Werner, C. Stable Isotopes as Indicators, Tracers, and Recorders of Ecological Change: Synthesis and Outlook. In Terrestrial Ecology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 399–405. ISBN 978-0-12-373627-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, J.; Hopmans, P.; Rennenberg, H.; Adams, M. Modern Tools to Tackle Traditional Concerns: Evaluation of Site Productivity and Pinus radiata Management via δ13C- and δ18O-Analysis of Tree-Rings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 285, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Wang, A.; Yuan, F.; Guan, D.; Wu, J. Relationship Between Tree Ring δ13C and Net Primary Productivity of Pinus koraiensis in Changbai Mountain, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 3327–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarchi, F.; Cherubini, P.; Pretzsch, H.; Tonon, G. The Increase of Atmospheric CO2 Affects Growth Potential and Intrinsic Water-Use Efficiency of Norway Spruce Forests: Insights from a Multi-Stable Isotope Analysis in Tree Rings of Two Alpine Chronosequences. Trees 2017, 31, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Yang, B. Review of Tree-ring Stable Carbon Isotopes. Quat. Sci. 2024, 44, 1044–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q.; Gou, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Y. Analysis on the Relationship Between Tree-Growth and Ecology Environment by 13C/12C Ratios of Tree Ring Cellulose. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2004, S2, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Brooks, J.R.; Roden, J.; Saurer, M. (Eds.) Stable Isotopes in Tree Rings: Inferring Physiological, Climatic and Environmental Responses: Tree Physiology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 8, ISBN 978-3-030-92697-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fardusi, M.J.; Ferrio, J.P.; Comas, C.; Voltas, J.; Resco De Dios, V.; Serrano, L. Intra-Specific Association between Carbon Isotope Composition and Productivity in Woody Plants: A Meta-Analysis. Plant Sci. 2016, 251, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmecheri, S.; Maxwell, R.S.; Taylor, A.H.; Davis, K.J.; Freeman, K.H.; Munger, W.J. Tree-Ring δ13C Tracks Flux Tower Ecosystem Productivity Estimates in a NE Temperate Forest. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 074011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Wang, A.; Gharun, M.; Saurer, M.; Yuan, F.; Guan, D.; Dai, G.; Wu, J. Tree-Ring δ13C of Pinus koraiensis is a Better Tracer of Gross Primary Productivity than Tree-Ring Width Index in an Old-Growth Temperate Forest. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, J.; Voltas, J.; Ferrio, J.P. Carbon Isotope Discrimination, Radial Growth, and NDVI Share Spatiotemporal Responses to Precipitation in Aleppo Pine. Trees 2015, 29, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, S.W.; Chase, T.N.; Rajagopalan, B.; Lee, E.; Lawrence, P.J. Southwestern U.S. Tree-ring Carbon Isotope Indices as a Possible Proxy for Reconstruction of Greenness of Vegetation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, 2008GL033894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, M.; Andreu-Hayles, L.; Smith, W.K.; Williams, A.P.; Hobi, M.L.; Allred, B.W.; Pederson, N. Tree-Ring Isotopes Capture Interannual Vegetation Productivity Dynamics at the Biome Scale. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Rotenberg, E.; Tatarinov, F.; Yakir, D. Association between Sap Flow-derived and Eddy Covariance-derived Measurements of Forest Canopy CO2 Uptake. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, F.; Rotenberg, E.; Yakir, D.; Klein, T. Forest GPP Calculation Using Sap Flow and Water Use Efficiency Measurements. BIO-Protoc. 2017, 7, e2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, H.; Gong, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, L. Tree-Ring Based Forest Model Calibrations with a Deep Learning Algorithm. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 569, 122154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, J.; Von Arx, G.; Nievergelt, D.; Wilson, R.; Van Den Bulcke, J.; Günther, B.; Loader, N.J.; Rydval, M.; Fonti, P.; Scharnweber, T.; et al. Scientific Merits and Analytical Challenges of Tree-Ring Densitometry. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 1224–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lan, Y.A. July–August Mean-Temperature Dataset Reconstructed based on the Maximum Latewood Density of Hailar Pine in the North Greater Khingan Mountains (1781–2013). J. Glob. Change Data Discov. 2022, 6, 395–401+572–578. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arrigo, R.D.; Malmstrom, C.M.; Jacoby, G.C.; Los, S.O.; Bunker, D.E. Correlation between Maximum Latewood Density of Annual Tree Rings and NDVI Based Estimates of Forest Productivity. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 2329–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, P.S.A.; Andreu-Hayles, L.; D’Arrigo, R.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Tucker, C.J.; Pinzón, J.E.; Goetz, S.J. A Large-Scale Coherent Signal of Canopy Status in Maximum Latewood Density of Tree Rings at Arctic Treeline in North America. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 100, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Díaz, A.; Gómez-Guerrero, A.; Vargas-Hernández, J.J.; Rozenberg, P.; Horwath, W.R. Long-Term Wood Micro-Density Variation in Alpine Forests at Central México and Their Spatial Links with Remotely Sensed Information. Forests 2020, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouriaud, O.; Teodosiu, M.; Kirdyanov, A.V.; Wirth, C. Influence of Wood Density in Tree-Ring-Based Annual Productivity Assessments and Its Errors in Norway Spruce. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 6205–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Rodriguez, D.R.; Tomazello-Filho, M. Clues to Wood Quality and Production from Analyzing Ring Width and Density Variabilities of Fertilized Pinus taeda Trees. New For. 2019, 50, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchi, P.F.; Khomik, M.; Frigo, D.; Arain, M.A.; Fonti, P.; Arx, G.V.; Castagneri, D. Revealing How Intra- and Inter-Annual Variability of Carbon Uptake (GPP) Affects Wood Cell Biomass in an Eastern White Pine Forest. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Bai, H.; Zhao, P.; Fang, S.; Xiang, Y.; Huang, X. Dendrochronology-Based Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Reconstruction in the Qinling Mountains, North-Central China. Forests 2022, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Xue, M.; Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Chen, B.; Dong, Y. A Decade’s Change in Vegetation Productivity and Its Response to Climate Change over Northeast China. Plants 2021, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, P.; Zheng, Z.; Bhatta, K.P.; Adhikari, Y.P.; Zhang, Y. Climate-Driven Plant Response and Resilience on the Tibetan Plateau in Space and Time; A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Li, M. July Mean Temperature Reconstruction for the Southern Tibetan Plateau Based on Tree-Ring Width Data during 1763–2020. Forests 2022, 13, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Luo, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Liang, E. Annual Ring Widths Are Good Predictors of Changes in Net Primary Productivity of Alpine Rhododendron Shrubs in the Sergyemla Mountains, Southeast Tibet. Plant Ecol. 2012, 213, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, Z. Warming Unsynchronised Tree Radial Growth and Regional Vegetation Canopy Growth in Semi-Arid Areas of North-Eastern China—A Case of Pinus sylvestris Var. Mongolica in Plantation. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2025, 69, 1969–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Qin, N.; Liu, X.; Jin, L. Vegetation Index Reconstruction and Linkage with Drought for the Source Region of the Yangtze River Based on Tree-Ring Data. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, M.; Kudo, S.; Iwama, C.; Nagano, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Harazono, Y.; Yoshikawa, K. Does Summer Warming Reduce Black Spruce Productivity in Interior Alaska? J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Morin, H.; Deslauriers, A.; Plourde, P.-Y. Predicting Xylem Phenology in Black Spruce under Climate Warming: Xylem Phenology under Climate Warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Su, Y. Relationship Between Radial Growth and NDVI of Larix gmelinii During Rapid Warming and Intermittent Warming. For. Eng. 2025, 41, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvenue, C.; Running, S.W. Impacts of Climate Change on Natural Forest Productivity–Evidence since the Middle of the 20th Century. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Eziz, A.; Halik, Ü.; Abliz, A.; Kurban, A. Precipitation and Temperature Influence the Relationship between Stand Structural Characteristics and Aboveground Biomass of Forests—A Meta-Analysis. Forests 2023, 14, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Q. Larix olgensis Growth–Climate Response between Lower and Upper Elevation Limits: An Intensive Study along the Eastern Slope of the Changbai Mountains, Northeastern China. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiao, L.; Hou, C.; Xu, H. Inconsistent Relationships between Tree Ring Width and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index in Montane Evergreen Coniferous Forests in Arid Regions. Trees 2022, 36, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lyu, L.; Liu, W.; Liang, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q.-B. Topographic Patterns of Forest Decline as Detected from Tree Rings and NDVI. CATENA 2021, 198, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yi, Y.; Jia, W.; Cai, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, Z. Applying Dendrochronology and Remote Sensing to Explore Climate-Drive in Montane Forests over Space and Time. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 237, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Bai, H.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Q. Multi-scale Periodic Variation of NDVI in July and its Response to Climatic Factors in the Taibai Mountain area. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 2131–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cui, J.; Li, J.; Peng, M.; Ma, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Microenvironmental Effects on Growth Response of Pinus massoniana to Climate at Its Northern Boundary in the Tongbai Mountains, Central China. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, O.; Shao, X. Long-Term Changes in the Tree Radial Growth and Intrinsic Water-Use Efficiency of Chuanxi Spruce (Picea likiangensis var. balfouriana) in Southwestern China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulehle, F.; Šamonil, P.; Urban, O.; Čáslavský, J.; Ač, A.; Vašíčková, I.; Kašpar, J.; Hubený, P.; Brázdil, R.; Trnka, M. Growth and Assemblage Dynamics of Temperate Forest Tree Species Match Physiological Resilience to Changes in Atmospheric Chemistry. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alla, A.Q.; Pasho, E.; Shallari, S. Tree Growth Variability in Pinus nigra Plantations Modulated by Climate and Soil Properties. Eur. J. For. Res. 2025, 144, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucker, T.; Avăcăriței, D.; Bărnoaiea, I.; Duduman, G.; Bouriaud, O.; Coomes, D.A. Climate Modulates the Effects of Tree Diversity on Forest Productivity. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F.; Keleş, S.Ö. Tree Species Richness Influence Productivity and Anatomical Characteristics in Mixed Fir-Pine-Beech Forests. Plant Ecol. 2023, 224, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholdaenko, Y.A.; Babushkina, E.A.; Belokopytova, L.V.; Zhirnova, D.F.; Koshurnikova, N.N.; Yang, B.; Vaganov, E.A. The More the Merrier or the Fewer the Better Fare? Effects of Stand Density on Tree Growth and Climatic Response in a Scots Pine Plantation. Forests 2023, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholdaenko, Y.A.; Belokopytova, L.V.; Zhirnova, D.F.; Upadhyay, K.K.; Tripathi, S.K.; Koshurnikova, N.N.; Sobachkin, R.S.; Babushkina, E.A.; Vaganov, E.A. Stand Density Effects on Tree Growth and Climatic Response in Picea obovata Ledeb. Plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 519, 120349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, M.; Bravo-Oviedo, A.; Ruiz-Peinado, R.; Condés, S. Tree Allometry Variation in Response to Intra- and Inter-Specific Competitions. Trees 2019, 33, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, D.I.; Tachauer, I.H.H.; Annighoefer, P.; Barbeito, I.; Pretzsch, H.; Ruiz-Peinado, R.; Stark, H.; Vacchiano, G.; Zlatanov, T.; Chakraborty, T.; et al. Generalized Biomass and Leaf Area Allometric Equations for European Tree Species Incorporating Stand Structure, Tree Age and Climate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 396, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Yin, T.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Qin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Fan, P.; Wang, H.; Zheng, P.; et al. Vegetation Greenness Dynamics in the Western Greater Khingan Range of Northeast China Based on Dendrochronology. Biology 2022, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulamsuren, C.; Hauck, M. Drought Stress Mitigation by Nitrogen in Boreal Forests Inferred from Stable Isotopes. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5211–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise, T.; Moorcroft, P.R. Quantifying Local Factors in Medium-Frequency Trends of Tree Ring Records: Case Study in Canadian Boreal Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Bugmann, H.; Fonti, P.; Rigling, A. Using a Retrospective Dynamic Competition Index to Reconstruct Forest Succession. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 254, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čada, V.; Svoboda, M.; Janda, P. Dendrochronological Reconstruction of the Disturbance History and Past Development of the Mountain Norway Spruce in the Bohemian Forest, Central Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 295, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonka, T.; Holeksa, J.; Fleischer, P.; Kapusta, P. A Tree-Ring Reconstruction of Wind Disturbances in a Forest of the Slovakian Tatra Mountains, Western Carpathians. J. Veg. Sci. 2010, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-G.; Deslauriers, A.; Rossi, S. Xylem Formation Can Be Modeled Statistically as a Function of Primary Growth and Cambium Activity. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, L.; Brunetti, M.; Baliva, M.; Förster, M.; Heinrich, I.; Piovesan, G.; Di Filippo, A. Modelling Fagus Sylvatica Stem Growth along a Wide Thermal Gradient in Italy by Incorporating Dendroclimatic Classification and Land Surface Phenology Metrics. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Tong, X.; Zhang, J.; Meng, P.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Yu, P. NIRv and SIF Better Estimate Phenology than NDVI and EVI: Effects of Spring and Autumn Phenology on Ecosystem Production of Planted Forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 315, 108819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Tree-ring width | Well-developed methodology; Cost-effective; Provides extended temporal coverage for productivity reconstruction; Direct reflection of radial growth rate. | Influenced by non-climatic factors; May exhibit lag or decoupling phenomena; Does not account for variations in wood density. |

| Tree-ring isotopes | Clear physiological mechanisms and interpretable correlation; Less affected by external disturbances; Highly sensitive to extreme climate events. | High technical complexity and cost; Precision of productivity reconstruction is affected by fractionation coefficients; Complex environmental signals may interfere with productivity interpretation. |

| Tree-ring density | Directly reflects productivity; Strong correlation with productivity under temperature-limited conditions; Provides clear seasonal signals. | High technical complexity and cost; Significant limitations in application for diffuse-porous broadleaf species productivity. |

| Anatomical properties | Capable of identifying seasonal carbon allocation; Allows for reconstruction of intra-annual productivity allocation patterns. | High technical complexity and cost; Anatomical structure easily affected by local disturbances; Low interannual variability; Non-normal statistical distributions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, R.; Li, M. Tree-Ring Proxies for Forest Productivity Reconstruction: Advances and Future Directions. Forests 2025, 16, 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121803

Yu R, Li M. Tree-Ring Proxies for Forest Productivity Reconstruction: Advances and Future Directions. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121803

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ruifeng, and Mingqi Li. 2025. "Tree-Ring Proxies for Forest Productivity Reconstruction: Advances and Future Directions" Forests 16, no. 12: 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121803

APA StyleYu, R., & Li, M. (2025). Tree-Ring Proxies for Forest Productivity Reconstruction: Advances and Future Directions. Forests, 16(12), 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121803