Biostimulation Effect of the Seaweed Extract (Ecklonia maxima Osbeck) and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis Ehrenberg) on the Growth of the European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment and Field Studies

2.2. Physico-Chemical Properties of Peat-Sawdust Substrate

2.3. Hydrothermal Conditions

2.4. Laboratory Studies on Biometric Features

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolte, A.; Czajkowski, T.; Cocozza, C.; Tognetti, R.; de Miguel, M.; Pšidová, E.; Ditmarová, Ĺ.; Dinca, L.; Delzon, S.; Cochard, H.; et al. Desiccation and mortality dynamics in seedlings of different European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) populations under extreme drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazol, A.; Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; de Luis, M.; del Castillo, E.M.; Serra-Maluquer, X. Summer drought and spring frost, but not their interaction, constrain European beech and silver fir growth in their southern distribution limits. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 278, 107695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausolf, K.; Wilm, P.; Härdtle, W.; Jansen, K.; Schuldt, B.; Sturm, K.; von Oheimb, G.; Hertel, D.; Leuschner, C.; Fichtner, A. Higher drought sensitivity of radial growth of European beech in managed than in unmanaged forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, A.R.; Weber, P. Drought-adaptation potential in Fagus sylvatica: Linking moisture availability with genetic diversity and dendrochronology. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, P.; Bugmann, H.; Pluess, A.R.; Walthert, L.; Rigling, A. Drought response and changing mean sensitivity of European beech close to the dry distribution limit. Trees 2013, 27, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, D.B.; Kržic, A.; Matović, B.; Orlović, S.; Duputié, A.; Djurdjević, V.; Galić, Z.; Stojnić, S. Prediction of the European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) xeric limit using a regional climate model: An example from Southeast Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 176, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Cano, F.J.; Gascó, A.; Cochard, H.; Nardini, A.; Mancha, J.A.; López, R.; Sánchez-Gómez, D. Variation in photosynthetic performance and hydraulic architecture across European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) populations supports the case for local adaptation to water stress. Tree Physiol. 2015, 35, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, L.; Stojanović, D.; Mladenović, E.; Lakićević, M.; Orlović, S. Potential elevation shift of the European beech stands (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Serbia. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barna, M. Natural regeneration of Fagus sylvatica L.: A review. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2011, 128, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Štefančík, I.; Vacek, Z.; Sharma, R.P.; Vacek, S.; Rösslová, M. Effect of thinning regimes on growth and development of crop trees in Fagus sylvatica stands of Central Europe over fifty years. Dendrobiology 2018, 79, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramreiter, M.; Grabner, M. The utilization of European beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Europe. Forests 2023, 14, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.; Pockman, W.T.; Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; Cobb, N.; Kolb, T.; Plaut, J.; Sperry, J.; West, A.; Williams, D.G.; et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: Why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 2008, 178, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, R.; Plichta, R.; Urban, J.; Volařík, D.; Hájíčková, M. The resistance and resilience of European beech seedlings to drought stress during the period of leaf development. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C. Drought response of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)—A review. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2020, 47, 125576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Z.; Vacek, Z.; Vacek, S.; Cukor, J.; Šimůnek, V.; Štefančík, I.; Brabec, P.; Králíček, I. European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.): A promising candidate for future forest ecosystems in Central Europe amid climate change. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2024, 70, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, M.; Panzarová, K.; Spyroglou, I.; Spíchal, L.; Buffagni, V.; Ganugi, P.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Lucini, L.; De Diego, N. Integration of phenomics and metabolomics datasets reveals different mode of action of biostimulants based on protein hydrolysates in Lactuca sativa L. and Solanum lycopersicum L. under salinity. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 808711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacruz-García, C.A.; Gracia Senilliani, M.; Gómez, A.T.; Ewens, M.M.; Yonny, M.E.; Villalba, G.F.; Nazareno, M.A. Biostimulants as forest protection agents: Do these products have an effect against abiotic stress on a forest native species? Aspects to elucidate their action mechanism. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 522, 120446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsfield, T.D.; Bentz, B.J.; Faccoli, M.; Jactel, H.; Brockerhoff, E.G. Forest health in a changing world: Effects of globalization and climate change on forest insect and pathogen impacts. Forestry 2016, 89, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeniyi, F.G.; Ewuola, E.O. A review of strategies aimed at adapting livestock to volatile climatic conditions in Nigeria. Niger. J. Anim. Prod. 2021, 48, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G.; Majid Wani, A.; Prusty, M.; Ray, M. Effect of globalization and climate change on forest—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojnić, S.; Suchocka, M.; Benito-Garzón, M.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; Cochard, H.; Bolte, A.; Cocozza, C.; Cvjetković, B.; De Luis, M.; Martinez-Vilalta, J.; et al. Variation in xylem vulnerability to embolism in European beech from geographically marginal populations. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Europe. State of Europe’s Forests 2015. Available online: https://foresteurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/soef_21_12_2015.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Marčiulynas, A.; Marčiulyniene, D.; Lynikiene, J.; Gedminas, A.; Vaičiukyne, M.; Menkis, A. Fungi and oomycetes in the irrigation water of forest nurseries. Forests 2020, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. The Science of Plant Biostimulants—A Bibliographic Analysis; Ad hoc Study Report to the European Commission DG ENTR. 2012. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5c1f9a38-57f4-4f5a-b021-cad867c1ef3c?utm (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Patel, J.S. Seaweed extract: Biostimulator of plant defense and plant productivity. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, D.C.; Birthal, P.S.; Kumara, T.M.K. Biostimulants for sustainable development of agriculture: A bibliometric content analysis. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Usha, A.; Rayirath, P.; Sowmyalakshmi, A.; Subramanian, A.; Jithesh, M.; Prasanth, A.; Rayorath, M.; Mark, D.; Hodges, A.; et al. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, J.S. Seaweed extract stimuli in plant science and agriculture. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Nanda, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B.N.; Mukherjee, A. Seaweed extracts: Enhancing plant resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1457500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, P.; Ali, N.; Saini, S.; Pati, P.K.; Pati, A.M. Physiological and molecular insight of microbial biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1041413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.; Bakker, P.A. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.S.; Vidya, P.; Balakumaran, M.D.; Ramya, G.K.; Nithya, K. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: A catalyst for advancing horticulture applications. Biotech. Res. Asia 2024, 21, 947–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.P.; Gomes, E.A.; de Sousa, S.M.; de Paula Lana, U.G.; Coelho, A.M.; Marriel, I.E.; de Oliveira-Paiva, C.A. Co-inoculation with tropical strains of Azospirillum and Bacillus is more efficient than single inoculation for improving plant growth and nutrient uptake in maize. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowicz, R.; Skrzypek, E.; Gleń-Karolczyk, K.; Krupa, M.; Biel, W.; Chłopicka, J.; Galanty, A. Effects of application of plant growth promoters, biological control agents and microbial soil additives on photosynthetic efficiency, canopy vegetation indices and yield of common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench). Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2021, 37, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Giordano, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Cozzolino, E.; Mori, M.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Plant- and seaweed-based extracts increase yield but differentially modulate nutritional quality of greenhouse spinach through biostimulant action. Agronomy 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, M.; Szmidla, H.; Sikora, K. The use of biostimulants containing Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jolis algal extract in the cultivation and protection of English oak (Quercus robur L.) seedlings in forest nurseries. Sylwan 2022, 166, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinantya, A.; Manea, A.; Ossola, A.; Leishman, M.R. Biostimulant application practices in Australian urban forestry. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2025, 53, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyhar, T.; Mughini, G.; Marchi, M. Influence of biostimulant application in containerized Eucalyptus globulus Labill. seedlings after transplanting. Dendrobiology 2019, 82, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10390; Soil Quality—Determination of pH. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 10694; Soil Quality: Determination of Organic and Total Carbon After Dry Combustion (Elementary Analysis). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- ISO 13878; Soil Quality: Determination of Total Nitrogen Content by Dry Combustion (“Elemental Analysis”). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Kappen, H. Bodenazidität; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Selyaninov, G.T. About climate agricultural estimation. Proc. Agric. Meteorol. 1928, 20, 165–177. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pallardy, S.G. Physiology of Woody Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, G.A.; Landis, T.D.; Dumroese, R.K.; Haase, D.L. Seedling Quality: Principles, Measurements, and Standards. In Forest Nursery Manual: Production of Bareroot Seedlings; Duryea, M.L., Landis, T.D., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, D.L. Morphological and physiological evaluations of seedling quality. In National Proceedings: Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations—2006; Proceedings RMRS-P-50; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Banach, J.; Kempf, M.; Skrzyszewska, K.; Olejnik, K. The effect of starter fertilization on the growth of seedlings of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Sylwan 2021, 165, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.; Kormanek, M.; Małek, S.; Durło, D.; Skrzyszewska, K. Effect of the changing seedlings density of Quercus robur L. grown in nursery containers on their morphological traits and planting suitability. Sylwan 2023, 167, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.D. Planting stock selection: Meeting biological needs and operational realities. In Forest Nursery Manual; Duryea, M.L., Landis, T.D., Eds.; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 1984; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B.E. Seedling morphological evaluation—What you can tell by looking. In Evaluating Seedling Quality: Principles, Procedures, and Predictive Abilities of Major Tests; Duryea, M.L., Ed.; Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 1985; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, A.; Leaf, A.L.; Hosner, J.F. Quality appraisal of white spruce and white pine seedling stock in nurseries. For. Chron. 1960, 36, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Shi, W.H.; Xing, X.J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.R.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.F.; Dong, L.H.; Liu, H.B. Study of the tobacco seedling vigor index model. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2014, 47, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Tibco. Tibco Statistica Design of Experiments. 2020. Available online: https://docs.tibco.com/pub/stat/14.0.0/doc/html/UsersGuide/GUID-BDE9EAC1-F806-4234-9A5F-DFDE4B8BA8BA.html?utm (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Corsi, S.; Ruggeri, G.; Zamboni, A.; Bhakti, P.; Espen, L.; Ferrante, A.; Noseda, M.; Varanini, Z.; Scarafoni, A. Bibliometric analysis of the scientific literature on biostimulants. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L.; Aguiar, N.O.; Jones, D.L.; Nebbioso, A.; Mazzei, P.; Piccolo, A. Humic and fulvic acids as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Saa, S. Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi, S.; Pizzeghello, D.; Schiavon, M.; Ertani, A. Plant biostimulants: Physiological responses induced by protein hydrolyzed-based products and humic substances in plant metabolism. Sci. Agric. 2016, 73, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Chaski, C.; Polyzos, N.; Petropoulos, S.A. Biostimulants Application: A Low Input Cropping Management Tool for Sustainable Farming of Vegetables. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, E.; Blaszczak, A.; Wiatrak, B.; Canady, M. Biostimulant mode of action. In Biostimulants for Crops from Seed Germination to Plant Development; Gupta, S., Van Staden, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, A.; Vetrano, F.; Esposito, A.; Miceli, A. Effects of NAA and Ecklonia maxima Extracts on Lettuce and Tomato Transplant Production. Agronomy 2022, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A.; Kamou, N.; Tzelepis, G.; Karamanoli, K.; Menkissoglu-Spiroudi, U.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Root Transcriptional and Metabolic Dynamics Induced by the Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacterium (PGPR) Bacillus subtilis Mbi600 on Cucumber Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D.L. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parađiković, N.; Teklić, T.; Zeljković, S.; Lisjak, M.; Špoljarević, M. Biostimulants research in some horticultural plant species—A review. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.C.; Bound, S.A.; Buntain, M. Biostimulants in agricultural and horticultural production. Hortic. Rev. 2022, 49, 35–95. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, J.; Malinowska, E.; Wiśniewska-Kadzajan, B.; Jankowski, K. Evaluation of the impact of the Ecklonia maxima extract on selected morphological features of yellow pine, spruce and thuja seedlings. J. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 17, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Plant biostimulants: Innovative tool for enhancing plant nutrition in organic farming. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 82, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Van Gerrewey, T.; Geelen, D. A meta-analysis of biostimulant yield effectiveness in field trials. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 836702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinantya, A.; Manea, A.; Leishman, M.R. Wpływ ścinania korzeni i stosowania biostymulatorów na powodzenie przesadzania sześciu pospolitych australijskich gatunków drzew miejskich. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Tabassum, B.; Fathi, A.; Allah, E. Bacillus subtilis: A plant-growth promoting rhizobacterium that also impacts biotic stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, Á.T. Bacillus subtilis. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.F.; da Cruz, S.P.; Botelho, G.R.; Flores, A.V. Inoculation of Pinus taeda seedlings with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Floresta Ambiente 2018, 25, e20160056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-M.; Zheng, F.; Liu, Z.-H.; Lan, H.-B.; Cui, Y.-H.; Gao, T.-G.; Roitto, M.; Wang, A.-F. Enhanced root and stem growth and physiological changes in Pinus bungeana Zucc. seedlings by microbial inoculant application. Forests 2022, 13, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Khaine, I.; Kwak, M.J.; Lee, H.K.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, W.Y.; Woo, S.Y. Physiological changes and growth promotion induced in poplar seedlings by the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis JS. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xing, S.; Ma, H.; Du, Z.; Ma, B. Cytokinin-producing, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria that confer resistance to drought stress in Platycladus orientalis container seedlings. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9155–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-H.; Wu, C.-W.; Chang, Y.-S. Applying Dickson Quality Index, Chlorophyll Fluorescence, and Leaf Area Index for Assessing Plant Quality of Pentas lanceolata. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zeng, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, H. Effects of Bacillus subtilis on Cucumber Seedling Growth and Photosynthetic System under Different Potassium Ion Levels. Biology 2024, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhou, B.; Bi, Y.; Chen, X.; Yao, S. Study on the Microbial Mechanism of Bacillus subtilis in Improving Drought Tolerance and Cotton Yield in Arid Areas. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ervin, E.H.; Schmidt, R.E. Seaweed extract, humic acid, and propiconazole improve tall fescue sod heat tolerance and posttransplant quality. HortScience 2003, 38, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.F.I.; El-Nahrawy, S.; El-Zawawy, H.A.H.; Omara, A.E.-D. Effective applications of Bacillus subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens as biocontrol agents of damping-off disease and biostimulation of tomato plants. Stresses 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, B.; Manfrini, L.; Lugli, S.; Tugnoli, A.; Boini, A.; Perulli, G.D.; Bresilla, K.; Venturi, M.; Grappadelli, L.C. Sweet cherry water relations and fruit production efficiency are affected by rootstock vigor. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 227, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant biostimulants to enhance abiotic stress resilience in crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor | Levels of the Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |

| Factor 1: Plant Growth Promoter— Biostimulant | 0 cm3·ha−1—Ecklonia maxima (0 dm3·ha−1—Kelpak SL) K0 | 960 cm3·ha−1—Ecklonia maxima (3 dm3·ha−1—Kelpak SL) K1 | 1920 cm3·ha−1—Ecklonia maxima (6 dm3·ha−1—Kelpak SL) K2 |

| Factor 2: Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria—Biofungicide | 0 g·ha−1—Bacillus subtilis (0 dm3·ha−1—Serenade ASO) SR0 | 112 g·ha−1 —Bacillus subtilis (8 dm3·ha−1—Serenade ASO) SR1 | 224 g·ha−1—Bacillus subtilis (16 dm3·ha−1—Serenade ASO) SR2 |

| Substrate Parameters (TTf-1 #) | Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before Sowing (24 April 2023) | After Seedlings Picking (11 October 2023) | ||

| pH | H2O | 5.22 | 5.93 |

| KCl | 4.68 | 4.72 | |

| Ncałk. [g·kg−1] | 6.31 | 5.11 | |

| Ccałk. [g·kg−1] | 350 | 258 | |

| Exchangeable cations | Ca2+ [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 13.49 | 12.74 |

| Mg2+ [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 4.06 | 1.21 | |

| K+ [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 7.19 | 5.84 | |

| Na+ [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 1.48 | 0.97 | |

| Sorption properties | Hydrolytic acidity Hh [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 27.05 | 24.27 |

| Sum of exchangeable cation of the soil complex [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 26.22 | 20.75 | |

| Sorption capacity of the soil complex T [cmol(+)·kg−1] | 53.26 | 45.02 | |

| Degree of saturation of the sorption complex with bases V [%] | 49.02 | 46.12 | |

| Bioavailable macronutrients | P [mg·kg−1] | 92.27 | 52.58 |

| K [mg·kg−1] | 2331.44 | 561.35 | |

| Mg [mg·kg−1] | 97.81 | 91.84 | |

| Volumetric density [Mg·m−3] | 5.52 | ||

| Solid phase density [Mg·m−3] | 1.32 | ||

| Total porosity [%] | 76.0 | ||

| Month | Sum of the Monthly Temperatures [°C] | Average Monthly Temperature [°C] | Rainfall [mm] | Difference Between Average Temperature and Multi-Year Average Temperature [°C] # | Difference Between Precipitation and Multiyear Precipitation [mm] # | Sielianinov Hydrothermal Index * [K] | Classification of the Month | Temperature Undercover [°C] | Moisture Content Undercover [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | 495 | 10.3 | 34.80 | −0.72 | −75.8 | 0.70 | Dry | 19.7 | 45.7 |

| June | 689 | 14.5 | 66.80 | 0.41 | −65.2 | 0.97 | Dry | 19.8 | 53.3 |

| July | 835 | 17.4 | 61.00 | 1.59 | −64.9 | 0.73 | Dry | Foil cover was removed from the tunnel | |

| August | 860 | 18.0 | 79.60 | 2.75 | −21.3 | 0.93 | Dry | ||

| September | 730 | 15.2 | 62.00 | 4.26 | −22.5 | 0.85 | Dry | ||

| Features | Ecklonia maxima | Bacillus subtilis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K0 * | K1 | K2 | p-Value | SR0 * | SR1 | SR2 | p-Value | |

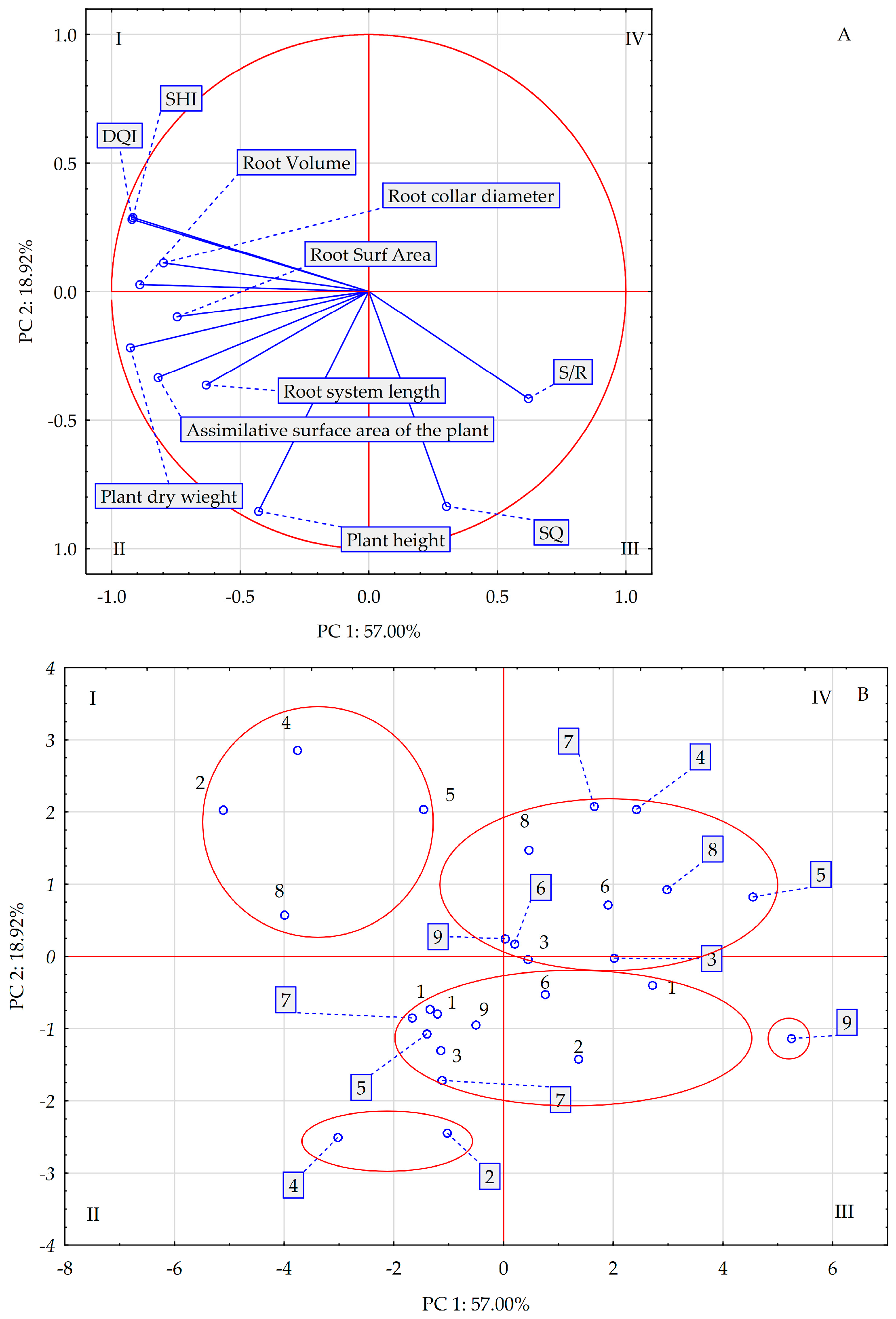

| Plant height [cm] | 37.2 ±2.9 a,** | 35.6 ±4.2 a | 35.7 ±3.6 a | 0.063 | 36.6 ± 4.5 a | 35.6 ± 3.7 a | 36.3 ± 2.5 a | 0.326 |

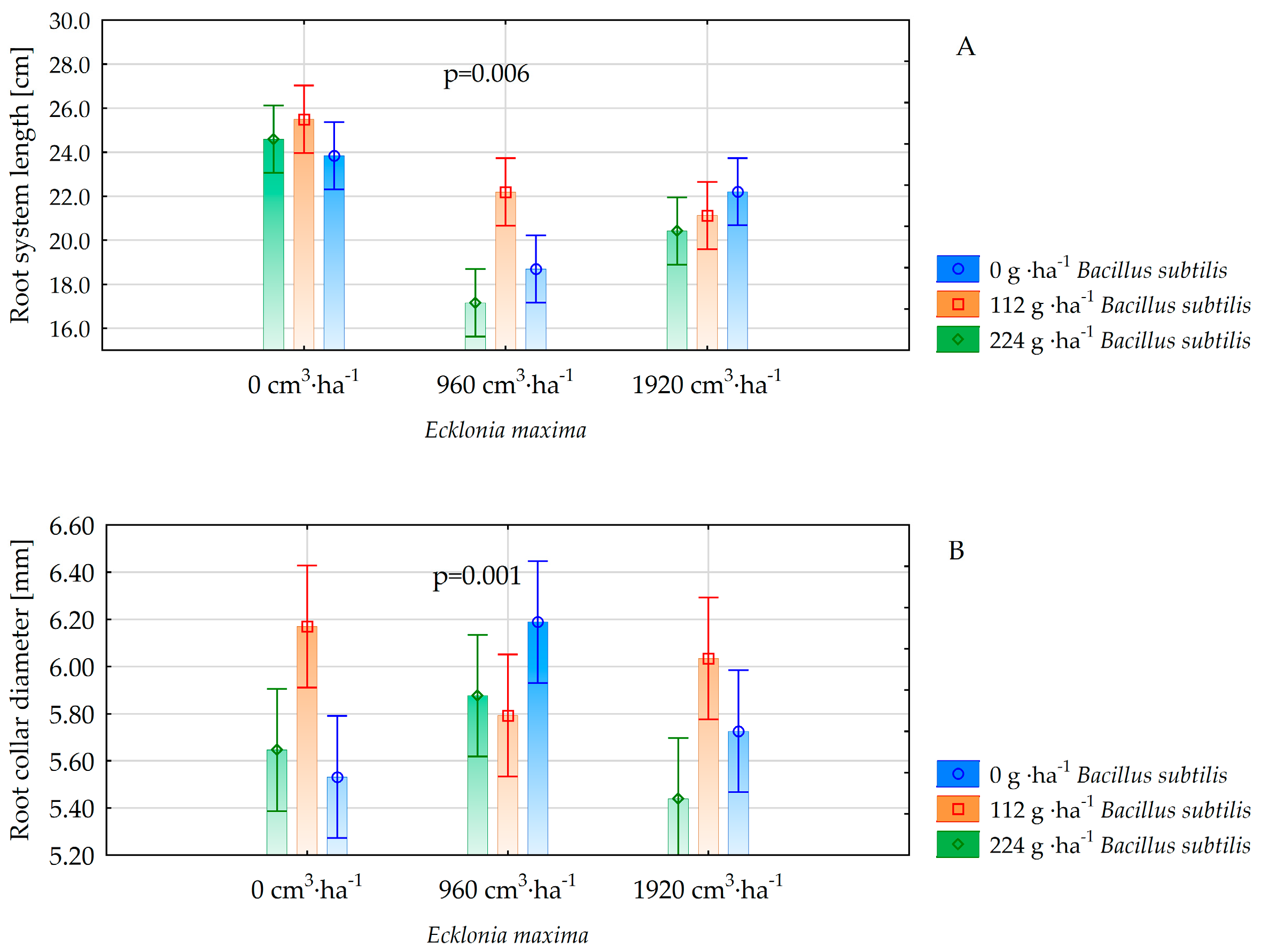

| Root system length [cm] | 24.6 ± 3.6 a | 19.3 ± 4.3 c | 21.2 ± 3.0 b | 0.000 | 21.6 ± 4.5 b | 22.9 ± 3.4 a | 20.7 ± 4.6 b | 0.002 |

| Root collar diameter [mm] | 5.78 ± 0.4 a | 5.95 ± 0.3 a | 5.73 ± 0.6 a | 0.101 | 5.82 ± 0.4 b | 6.00 ± 0.4 a | 5.65 ± 0.6 b | 0.006 |

| Stem dry weight [g] | 2.74 ± 0.4 a | 2.81 ± 0.5 a | 2.63 ± 0.5 a | 0.318 | 2.73 ± 0.6 a | 2.82 ± 0.5 a | 2.63 ± 0.4 a | 0.300 |

| Root system dry weight [g] | 2.29 ± 0.5 a | 2.28 ± 0.5 a | 2.26 ± 0.5 a | 0.955 | 2.37 ± 0.5 a | 2.36 ± 0.6 a | 2.10 ± 0.3 b | 0.027 |

| Leaves dry weight [g] | 1.01 ± 0.1 a | 0.97 ± 0.1 a | 0.99 ± 0.2 a | 0.722 | 0.95 ± 0.1 a | 1.04 ± 0.2 a | 0.97 ±0.1 a | 0.065 |

| Plant dry weight [g] | 6.04 ± 0.9 a | 6.06 ± 1.0 a | 5.87 ± 1.2 a | 0.704 | 6.04 ± 1.1 a | 6.22 ± 1.2 a | 5.70 ± 0.8 a | 0.104 |

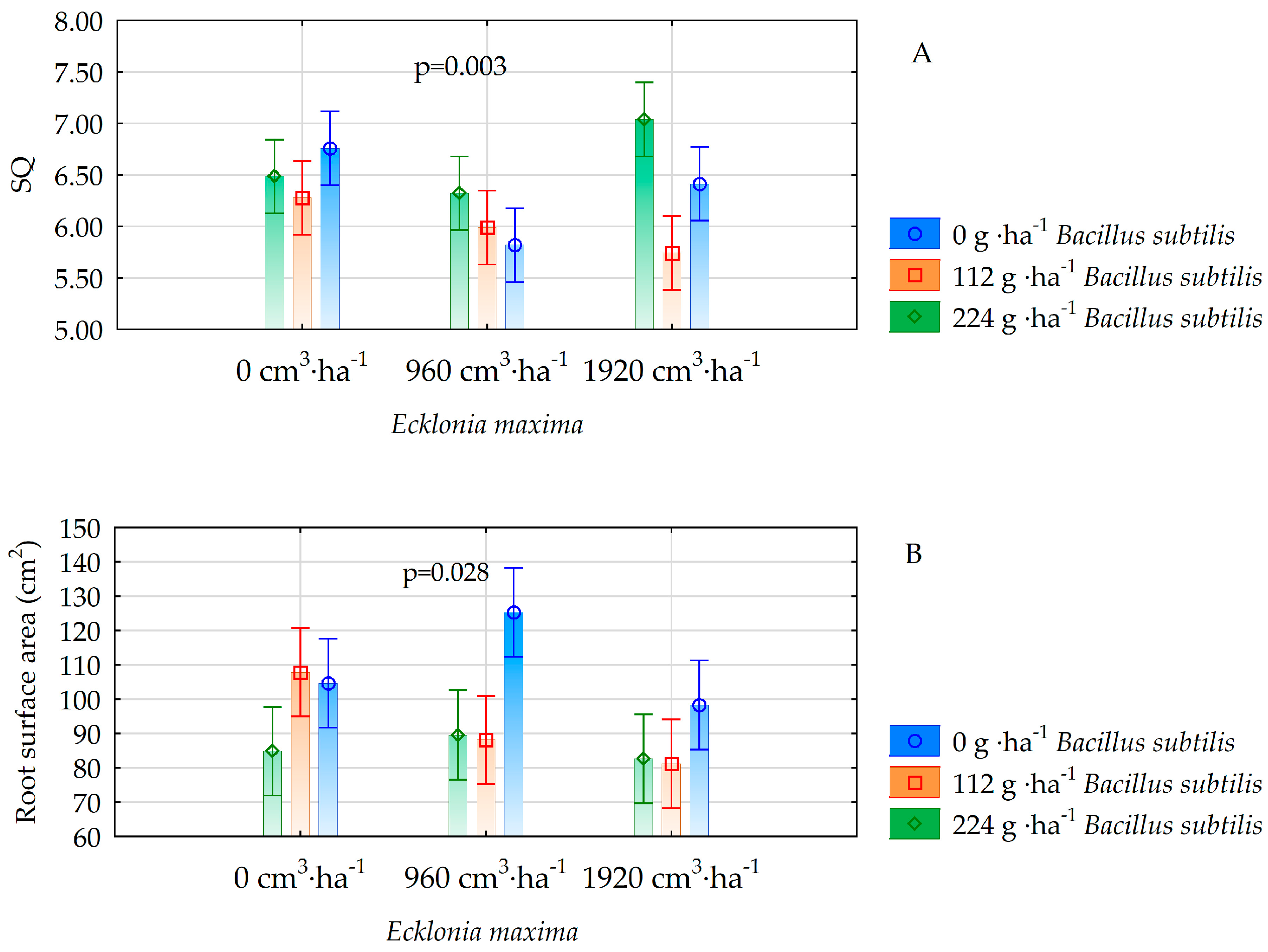

| SQ | 6.51 ± 0.5 a | 6.04 ± 0.5 b | 6.40 ± 0.5 a | 0.005 | 6.33 ± 0.7 b | 6.00 ± 0.6 b | 6.62 ± 0.7 a | 0.000 |

| S/R | 1.28 ± 0.2 a | 1.34 ± 0.2 a | 1.26 ± 0.1 a | 0.307 | 1.21 ± 0.2 b | 1.33 ± 0.2 a | 1.34 ± 0.1 a | 0.040 |

| DQI | 0.67 ± 0.2 a | 0.71 ± 0.2 a | 0.67 ± 0.3 a | 0.383 | 0.69 ± 0.2 b | 0.74 ± 0.2 a | 0.62 ± 0.2 b | 0.004 |

| SHI | 6.19 ± 1.7 a | 6.21 ± 1.7 a | 6.21 ± 1.4 a | 0.998 | 6.47 ± 1.0 a | 6.56 ± 1.6 a | 5.59 ± 0.9 b | 0.008 |

| Assimilative surface area of the plant [cm2] | 214.6 ± 26.1 a | 187.3 ± 24.5 b | 206.0 ± 29.4 ab | 0.014 | 209.6 ± 29.4 a | 204.8 ± 33.0 a | 193.5 ± 27.2 a | 0.223 |

| Assimilative area of leaf [cm2] | 11.3 ± 0.9 a | 11.2 ± 1.3 | 10.9 ± 1.1 a | 0.594 | 11.6 ± 0.8 a | 11.2 ± 1.0 ab | 10.6 ± 0.6 b | 0.025 |

| Leaves number in the plant [pcs.] | 20.4 ± 2.7 a | 17.9 ± 2.4 b | 19.7 ± 2.4 ab | 0.044 | 19.2 ± 1.7 a | 19.3 ± 2.0 a | 19.5 ± 2.2 a | 0.963 |

| Root system area [cm2] | 99.1 ± 15.2 ab | 101.0 ± 17.8 a | 87.4 ± 16.2 b | 0.024 | 109.4 ± 21.7 a | 92.4 ± 21.4 b | 85.7 ± 7.34 b | 0.000 |

| Root system volume [cm3] | 1.30 ± 0.3 a | 1.30 ± 0.3 a | 1.16 ± 0.2 b | 0.049 | 1.39 ± 0.3 | 1.23 ± 0.3 b | 1.14 ± 0.1 b | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krupa, M.; Banach, J.; Małek, S.; Witkowicz, R. Biostimulation Effect of the Seaweed Extract (Ecklonia maxima Osbeck) and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis Ehrenberg) on the Growth of the European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Seedlings. Forests 2025, 16, 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121796

Krupa M, Banach J, Małek S, Witkowicz R. Biostimulation Effect of the Seaweed Extract (Ecklonia maxima Osbeck) and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis Ehrenberg) on the Growth of the European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Seedlings. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121796

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrupa, Mateusz, Jacek Banach, Stanisław Małek, and Robert Witkowicz. 2025. "Biostimulation Effect of the Seaweed Extract (Ecklonia maxima Osbeck) and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis Ehrenberg) on the Growth of the European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Seedlings" Forests 16, no. 12: 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121796

APA StyleKrupa, M., Banach, J., Małek, S., & Witkowicz, R. (2025). Biostimulation Effect of the Seaweed Extract (Ecklonia maxima Osbeck) and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (Bacillus subtilis Ehrenberg) on the Growth of the European Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Seedlings. Forests, 16(12), 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121796