Impacts of Human Recreational Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition and Diversity in Urban Forest in Changchun, Northeast China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Plot Layout and Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.4. Determination of Soil Microbial Composition and Diversity

2.5. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Human Recreational Activity Disturbances on Soil Properties

3.2. Effects of Human Recreational Activities on the Composition and Diversity of Soil Bacterial Communities

3.2.1. Analysis of Dilution Curves and Shannon Wiener Curves at OTU Levels

3.2.2. Effects of Human Recreational Activity Disturbances on the OTU Composition of Soil Bacteria

3.2.3. Impacts of Human Recreational Activities Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition

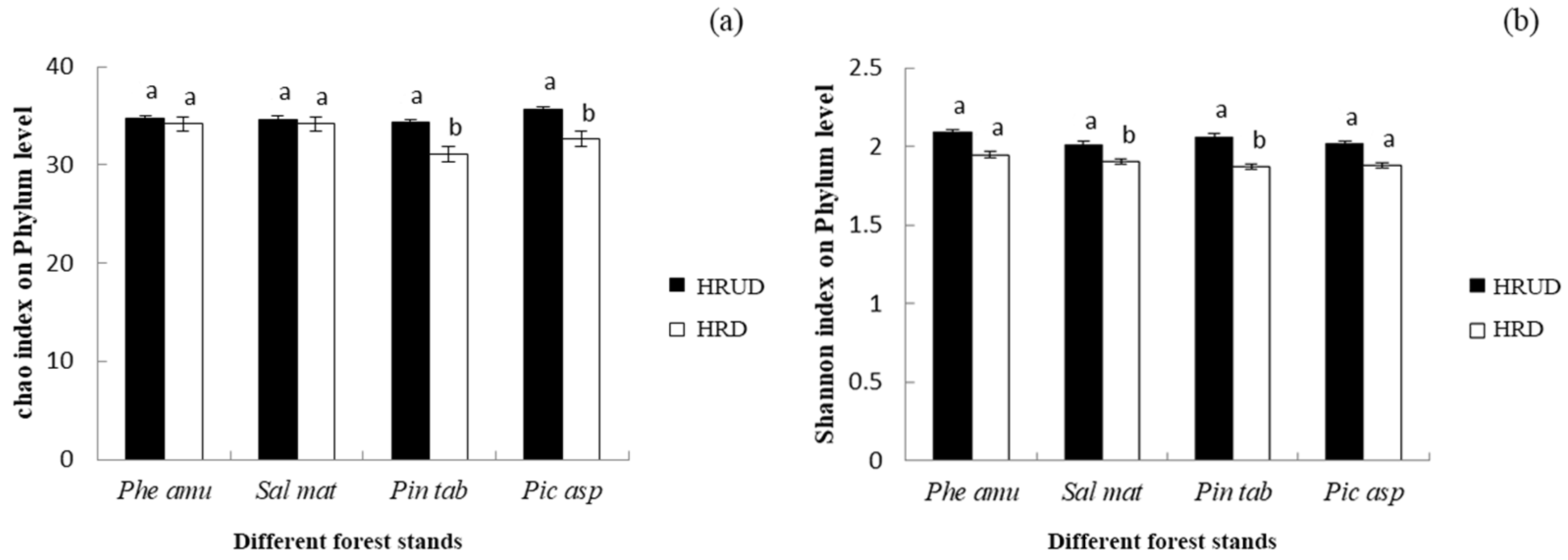

3.2.4. Effects of Human Recreational Disturbance on Soil Bacterial Diversity

3.3. Correlation Between Soil Properties and Soil Bacterial Communities

3.3.1. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

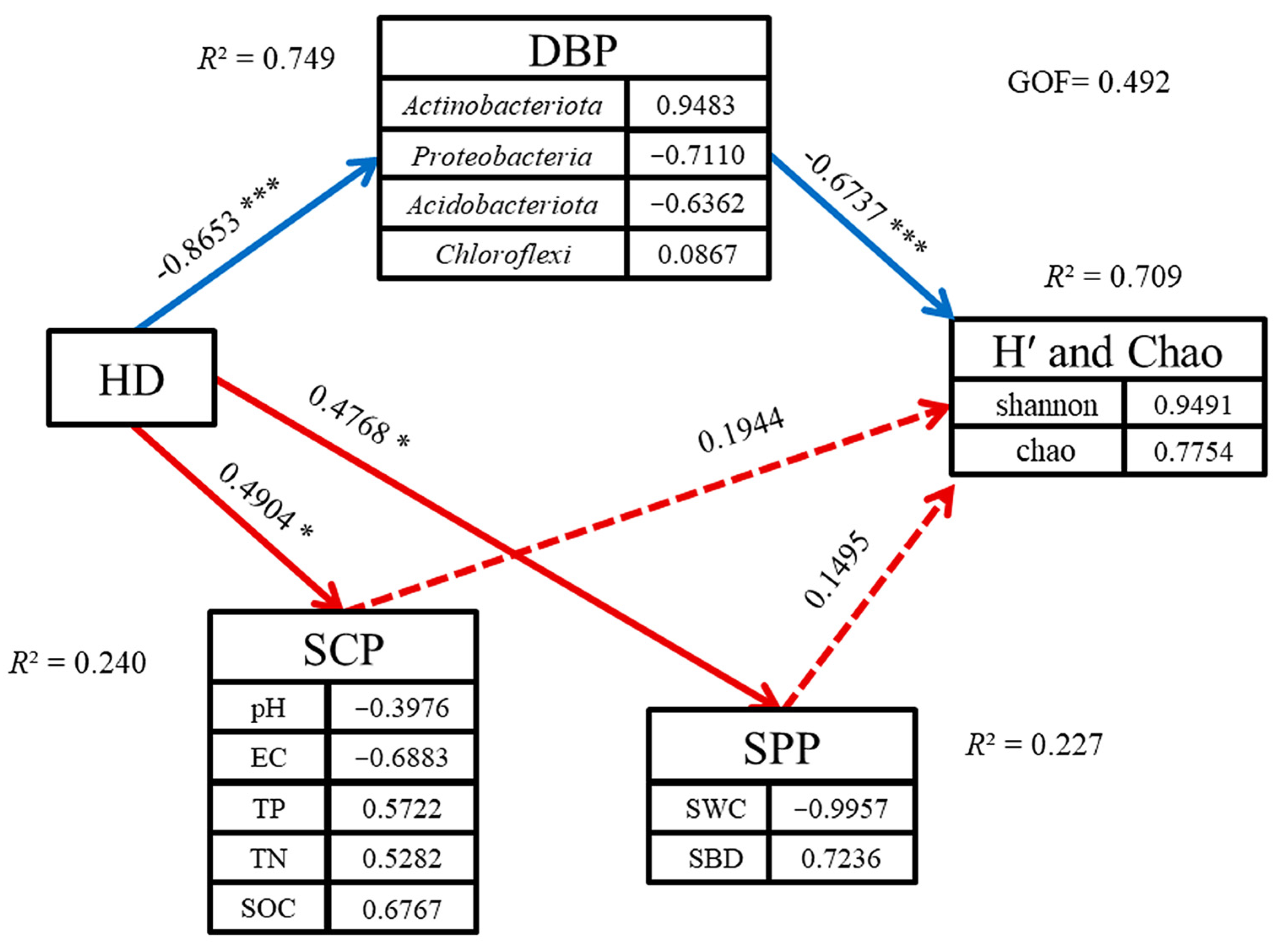

3.3.2. PLS-SEM Analysis of Recreational Disturbance Impacts on Soil Microbial Systems

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Human Recreational Activity Disturbances on Soil Properties

4.2. Effects of Human Recreational Activities on the Composition and Diversity of Soil Bacterial Communities

4.3. Correlations Between Soil Properties and Soil Microorganisms

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Implement strategic zoning to separate high-intensity recreational areas from ecologically sensitive soil zones. Use permeable paving materials (e.g., anticorrosive wood or porous concrete) in activity zones to reduce soil compaction, and install clear signage to prohibit off-trail trampling.

- Integrate adaptive management practices: Limit visitor density in fragile soil areas through timed access or capacity controls. Regularly aerate compacted soils in high-use zones and apply organic mulch to restore microbial activity and nutrient cycling.

- Establish long-term monitoring protocols for soil health indicators, including bulk density, organic matter content, and microbial diversity. Use findings to adjust zoning boundaries or restrict activities in areas showing signs of degradation.

- Promote public engagement through educational campaigns, highlighting the link between soil biodiversity and ecosystem services (e.g., water filtration, carbon sequestration). Encourage community participation in soil restoration initiatives (e.g., native plantings).

- Integrate microbial conservation into urban planning. Recreational disturbances reduce soil bacterial diversity and impair microbial functions. Managing visitor access is therefore essential to preserving nutrient cycling and carbon storage services. Protecting soil microbial communities must become a priority in sustainable park management to maintain urban forest health.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.Q.; Xiao, F.J. Assessing changes in the value of forest ecosystem services in response to climate change in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, R.; Samson, R.; Alonso, R.; Amorim, J.H.; Cariñanos, P.; Churkina, G.; Fares, S.; Le Thiec, D.; Niinemets, Ü.; Mikkelsen, T.N.; et al. Functional traits of urban trees: Air pollution mitigation potential. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.L.; Challacombe, J.F.; Janssen, P.H.; Henrissat, B.; Coutinho, P.M.; Wu, M.; Xie, G.; Haft, D.H.; Sait, M.L.; Badger, J.H.; et al. Three Genomes from the phylum Acidobacteria provide insight into the lifestyles of these microorganisms in soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2046–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, W.; Lv, H.L.; Xiao, L.; Wang, H.Y.; Du, H.J.; He, X.Y. The effect of urbanization gradients and forest types on microclimatic regulation by trees, in association with climate, tree sizes and species compositions in Harbin city, northeastern China. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Tao, J.; Li, G.; Jiang, M.Y.; Aii, L.; Jiang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.F.; Chen, Q.B. Effects of walking in bamboo forest and city environments on brainwave activity in young adults. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 9653857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrakiewicz-Gierałt, K.; Gmyrek, K.; Pliszko, A. Does the distance from the formal path affect the richness, abundance and diversity of geophytes in urban forests and parks? Forests 2023, 14, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, P.C.; Aryal, C.; Bhusal, K.; Chapagain, D.; Dhamala, M.K.; Maharjan, S.R.; Chhetri, P.K. Forest structure and anthropogenic disturbances regulate plant invasion in urban forests. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, F.; Thompson, K.A.; Carlyle, C.N.; Quideau, S.A.; Bork, E.W. Access Matting Reduces Mixedgrass Prairie Soil and Vegetation Responses to Industrial Disturbance. Environ. Manag. 2019, 64, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhou, C.; Yu, Z.; Xu, C.-Y. Soil moisture dynamics and associated rainfall-runoff processes under different land uses and land covers in a humid mountainous watershed. J. Hydrol. 2024, 636, 131249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degens, B.P.; Schipper, L.A.; Sparling, G.P.; Vojvodic-Vukovic, M. Decreases in organic C reserves in soils can reduce the catabolic diversity of soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Biogeochemical C and N cycles in urban soils. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Luo, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Han, Q.; Huang, B. Effects of root-irrigation with metalaxyl-M and hymexazol on soil physical and chemical properties, enzyme activity, and the fungal diversity, community structure and function. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2024, 59, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Smalla, K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 68, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.B.; Chen, D.S.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.M.; Zhang, S.G. Effects of mixed coniferous and broad-leaved litter on bacterial and fungal nitrogen metabolism pathway during litter decomposition. Plant Soil 2020, 451, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Holmes, W.E.; White, D.C.; Peacock, A.D.; Tilman, D. Plant diversity, soil microbial communities, and ecosystem function: Are there any links? Ecology 2003, 84, 2042–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwin, K.H.; Wardle, D.A.; Greenfield, L.G. Ecological consequences of carbon substrate identity and diversity in a laboratory study. Ecology 2006, 87, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preem, J.K.; Truu, J.; Truu, M.; Mander, Ü.; Oopkaup, K.; Lohmus, K.; Helmisaari, H.S.; Uri, V.; Zobel, M. Bacterial community structure and its relationship to soil physico-chemical characteristics in alder stands with different management histories. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 49, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Huang, Y.J.; Tang, S.L.; Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Chiu, C.Y. Bacterial community diversity in undisturbed perhumid montane forest soils in Taiwan. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 59, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.W.; Liu, S.R.; Wang, J.X.; Zhu, X.L. Factors affecting spatial variation of annual apparent Q10 of soil respiration in two warm temperate forests. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.F.; Fu, B.J.; Zheng, X.X.; Liu, G.H. Plant biomass, soil water content and soil N:P ratio regulating soil microbial functional diversity in a temperate steppe: A regional scale study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Z. Assessing bacterial diversity in soil. J. Soils Sediments 2008, 8, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholier, T.; Lavrinienko, A.; Brila, I.; Tukalenko, E.; Hindström, R.; Vasylenko, A.; Cayol, C.; Ecke, F.; Singh, N.J.; Forsman, J.T.; et al. Urban forest soils harbour distinct and more diverse communities of bacteria and fungi compared to less disturbed forest soils. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowd, E.J.; Banks, S.C.; Bissett, A.; May, T.W.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Disturbance alters the forest soil microbiome. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.S.; Coomes, D.A.; Du, X.J.; Hsieh, C.F.; Sun, I.F.; Chao, W.C.; Mi, X.C.; Ren, H.B.; Wang, X.G.; Hao, Z.Q.; et al. A general combined model to describe tree-diameter distributions within subtropical and temperate forest communities. Oikos 2013, 122, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Liu, S.R.; Wang, J.X.; Zhu, X.L.; Zhang, Y.D.; Liu, X.J. Variation in soil respiration under the tree canopy in a temperate mixed forest, central China, under different soil water conditions. Ecol. Res. 2014, 29, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Hui, N.; Jumpponen, A.; Lu, C.; Pouyat, R.; Szlavecz, K.; Wardle, D.A.; Yesilonis, I.; Setälä, H.; Kotze, D.J. Urbanization leads to asynchronous homogenization of soil microbial communities across biomes. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2025, 25, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christel, A.; Dequiedt, S.; Chemidlin-Prevost-Boure, N.; Mercier, F.; Tripied, J.; Comment, G.; Djemiel, C.; Bargeot, L.; Matagne, E.; Fougeron, A.; et al. Urban land uses shape soil microbial abundance and diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, X. Evolution of urban expansion and its microclimate in Changchun. Remote Sens. Inf. 2020, 35, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Dong, Y.L.; Guo, Y.J.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, G.D.; Ma, Z.J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Ren, Z.B.; Wang, W.J. Urban forest soil is becoming alkaline under rapid urbanization. Catena 2023, 224, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cui, S.; Zheng, H.; He, X.; Tang, Z.; Shen, S.Z.G. Species composition and community structure of Pinus tabuliformis forest in the South Lake Park in Changchun. Chin. J. Ecol. 2019, 38, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.; David, C.; Caroline, S.; Phillip, S. Standard Soil Methods for Long-Term Ecological Research; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampurlanés, J.; Cantero-Martínez, C. Soil Bulk Density and Penetration Resistance under Different Tillage and Crop Management Systems and Their Relationship with Barley Root Growth. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golui, D.; Datta, S.C.; Das, R. Determination of Soil pH and Electrical Conductivity by Different Methods: Comparison and interpretation; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, S.M.M.; Habibullah, M. Determination of Organic Carbon of Soil by the Walkley & Black Method; Jashore University of Science and Technology: Jashore, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.L.; Page, A.L.; Helmke, P.A.; Loeppert, R.H.; Soltanpour, P.N.; Tabatabai, M.A.; Johnston, C.T.; Sumner, M.E. Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kalahroudi, Z.; Zadeh, M.; Mahini, A.; Kiani, F.; Najafinejad, A. Impacts of tourist trampling and topography on soil quality characteristics in recreational trails. Soil Environ. 2023, 42, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, E.; Reader, R.J. Impacts of experimentally applied mountain biking and hiking on vegetation and soil of a deciduous forest. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Li, W.; Cai, L.; Zhang, L.; Pan, H.; Feng, Q.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Effects of human disturbance on natural secondary forests in China: I. Tree growth, regeneration and community structure. J. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, N.; Sun, G. Use of mulberry-soybean intercropping in salt-alkali soil impacts the diversity of the soil bacterial community. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBruyn Jennifer, M.; Nixon Lauren, T.; Fawaz Mariam, N.; Johnson Amy, M.; Radosevich, M. Global biogeography and quantitative seasonal dynamics of gemmatimonadetes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6295–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilimburg, A.; Monz, C.; Kehoe, S. Profile: Wildland recreation and human waste: A eeview of problems, practices, and concerns. Environ. Manag. 2000, 25, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiernaux, P.; Bielders, C.L.; Valentin, C.; Bationo, A.; Fernández-Rivera, S. Effects of livestock grazing on physical and chemical properties of sandy soils in Sahelian rangelands. J. Arid Environ. 1999, 41, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaig, A.E.; Glover, L.A.; Prosser, J.I. Molecular analysis of bacterial community structure and diversity in unimproved and improved upland grass pastures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.J.; Lin, J.; Guo, X.P.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.S.; Zhao, Y.P.; Zhang, J.C. Impacts of forest conversion on soil bacterial community composition and diversity in subtropical forests. Catena 2019, 175, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacmaga, M.; Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Kucharski, J.; Paprocki, L. Role of forest site type in determining bacterial and biochemical properties of soil. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Luo, M.Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Jia, X.; Kang, S.Z.; Yang, S.Y.; Mu, Q. Spatial patterns of dominant bacterial community components and their influential factors in the southern Qinling Mountains, China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1024236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; Ye, Y. Analysis on diversity of soil bacterial community under different land use patterns in saline-alkali land. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2019, 39, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachar, A.; Al-Ashhab, A.; Soares, M.I.M.; Sklarz, M.Y.; Angel, R.; Ungar, E.D.; Gillor, O. Soil microbial abundance and diversity along a low precipitation gradient. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, K.; Deng, P.; Ma, R.; Wang, F.; Wen, Z.; Xu, X. Changes of soil bacterial community structure and diversity from conversion of masson pine secondary forest to slash pine and chinese fir plantations. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2022, 31, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlbrooke, D. Effect of irrigation and grazing animals on soil quality measurements in the north otago rolling downlands of new zealand. Soil Use Manag. 2008, 24, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Jeffries, T.; Eldridge, D.; Ochoa, V.; Gozalo, B.; Quero, J.; García-Gómez, M.; Gallardo, A.; Ulrich, W.; et al. Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15684–15689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Jin, K.; Struik, P.C.; Sun, S.; Ji, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Soil bacterial and fungal communities are linked with plant functional types and soil properties under different grazing intensities. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.; Dale, D. Trampling effects of hikers, motorcycles and horses in meadows and forests. J. Appl. Ecol. 1978, 15, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrat, S.; Horrigue, W.; Dequietd, S.; Saby, N.P.A.; Lelièvre, M.; Nowak, V.; Tripied, J.; Régnier, T.; Jolivet, C.; Arrouays, D.; et al. Mapping and predictive variations of soil bacterial richness across France. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, V.; Spor, A.; Mathieu, O.; Lévèque, J.; Terrat, S.; Plassart, P.; Regnier, T.; Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H.; Roggero, P.P.; et al. Shifts in microbial diversity through land use intensity as drivers of carbon mineralization in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, O.; Fernandes, A.; Tupy, S.; Almeida, L.; Creevey, C.; Santana, M. Insights into plant interactions and the biogeochemical role of the globally widespread Acidobacteriota phylum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.J.; Niu, Z.J.; Liu, T.N.; Su, Y.Z. Responses of Soil Bacterial Structure and Nitrogen Metabolism to Haloxylon ammodendron Restoration in an Oasis-Desert Ecotone of Northwestern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 8454–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hodzic, J.; Su, J.; Zheng, S.; Bai, Y. A dataset of plant and microbial community structure after long-term grazing and mowing in a semiarid steppe. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, S.; Nipattasuk, W. Quantification of the effects of soil compaction on water flow using dye tracers and image analysis. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 19, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Marques, J.; Shahidian, S.; Carreira, E.; Marques da Silva, J.; Paixão, L.; Paniagua, L.L.; Moral, F.; Ferraz de Oliveira, I.; Sales-Baptista, E. Sensing and mapping the effects of cow trampling on the soil compaction of the montado mediterranean ecosystem. Sensors 2023, 23, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, T.J.; Schütte, U.M.E.; Drown, D.M. Soil Disturbance Affects Plant Productivity via Soil Microbial Community Shifts. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 619711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, P.A.; Sarr, A.; Kaisermann, A.; Lévêque, J.; Mathieu, O.; Guigue, J.; Karimi, B.; Bernard, L.; Dequiedt, S.; Terrat, S.; et al. High microbial diversity promotes soil ecosystem functioning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02738-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Spor, A.; Hénault, C.; Bru, D.; Bizouard, F.; Jones, C.M.; Sarr, A.; Maron, P.A. Loss in microbial diversity affects nitrogen cycling in soil. ISME J 2013, 7, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Nie, H.; Sun, X.; Dong, L.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. The effect of human trampling activity on a soil microbial community at the urban forest Park. Forests 2023, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Xing, Z. Impact of human trampling on biological soil crusts determined by soil microbial biomass, enzyme activities and nematode communities in a desert ecosystem. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2018, 87, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Sun, J.; He, T.; Hu, B. Effects of long-term human disturbances on soil microbial diversity and community structure in a karst grassland ecosystem of northwestern Guangxi, China. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 45, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Ren, H.D.; Li, S.; Leng, X.H.; Yao, X.H. Soil bacterial community structure and co-occurrence pattern during vegetation restoration in karst rocky desertification area. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zheng, C.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Han, X.M.; Yang, G.B.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.K. Impact of ecological restoration of rocky desertification on soil biodiversity in karst area: A review. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Kong, B.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y. Variation of soil organic carbon and physical properties in relation to land uses in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. Comparative analysis of soil microbial composition of four typical vegetation communities in Momoge National Nature Reserve, Jilin Province. Chin. J. Ecol. 2024, 43, 2988–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, C.G.; Watanabe, T.; Murase, J.; Asakawa, S.; Kimura, M. Identification of microbial communities that assimilate substrate from root cap cells in an aerobic soil using a DNA-SIP approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.S.; He, T.H.; Feng, Y.Q.; Cui, Q.; Chen, X.Q.; Zhao, M.T.; Qiu, W.J. Characteristics and distribution of soil bacterial of salt marsh tidal wetland in Ordos Platform. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 3345–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Zheng, S.L.; Ding, J.W.; Wang, O.M.; Liu, F.H. Spatial variation in bacterial community in natural wetland-river-sea ecosystems. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazi, S.; Amalfitano, S.; Pernthaler, J.; Puddu, A. Bacterial communities associated with benthic organic matter in headwater stream microhabitats. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, J. Anthropogenic activities change the relationship between microbial community taxonomic composition and functional attributes. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 6663–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Struik, P.C.; Ren, J.; Wang, C.; Jin, K. Editorial: Exploring the effects of human activities and climate change on soil microorganisms in grasslands. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1515648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Ma, X.; Lu, Z.; Song, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chang, B.; Gong, C.; et al. Impacts of Human Recreational Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition and Diversity in Urban Forest in Changchun, Northeast China. Forests 2025, 16, 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121798

Zhang D, Ma X, Lu Z, Song Y, Yao X, Zhang H, Zhang X, Zhang X, Chang B, Gong C, et al. Impacts of Human Recreational Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition and Diversity in Urban Forest in Changchun, Northeast China. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121798

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dan, Xinyuan Ma, Ziyue Lu, Yuhang Song, Xiao Yao, Hongjian Zhang, Xudong Zhang, Xiaolei Zhang, Baoliang Chang, Chao Gong, and et al. 2025. "Impacts of Human Recreational Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition and Diversity in Urban Forest in Changchun, Northeast China" Forests 16, no. 12: 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121798

APA StyleZhang, D., Ma, X., Lu, Z., Song, Y., Yao, X., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Chang, B., Gong, C., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Impacts of Human Recreational Disturbances on Soil Bacterial Community Composition and Diversity in Urban Forest in Changchun, Northeast China. Forests, 16(12), 1798. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121798