Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Global Review of Practices, Species, and Ecological Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

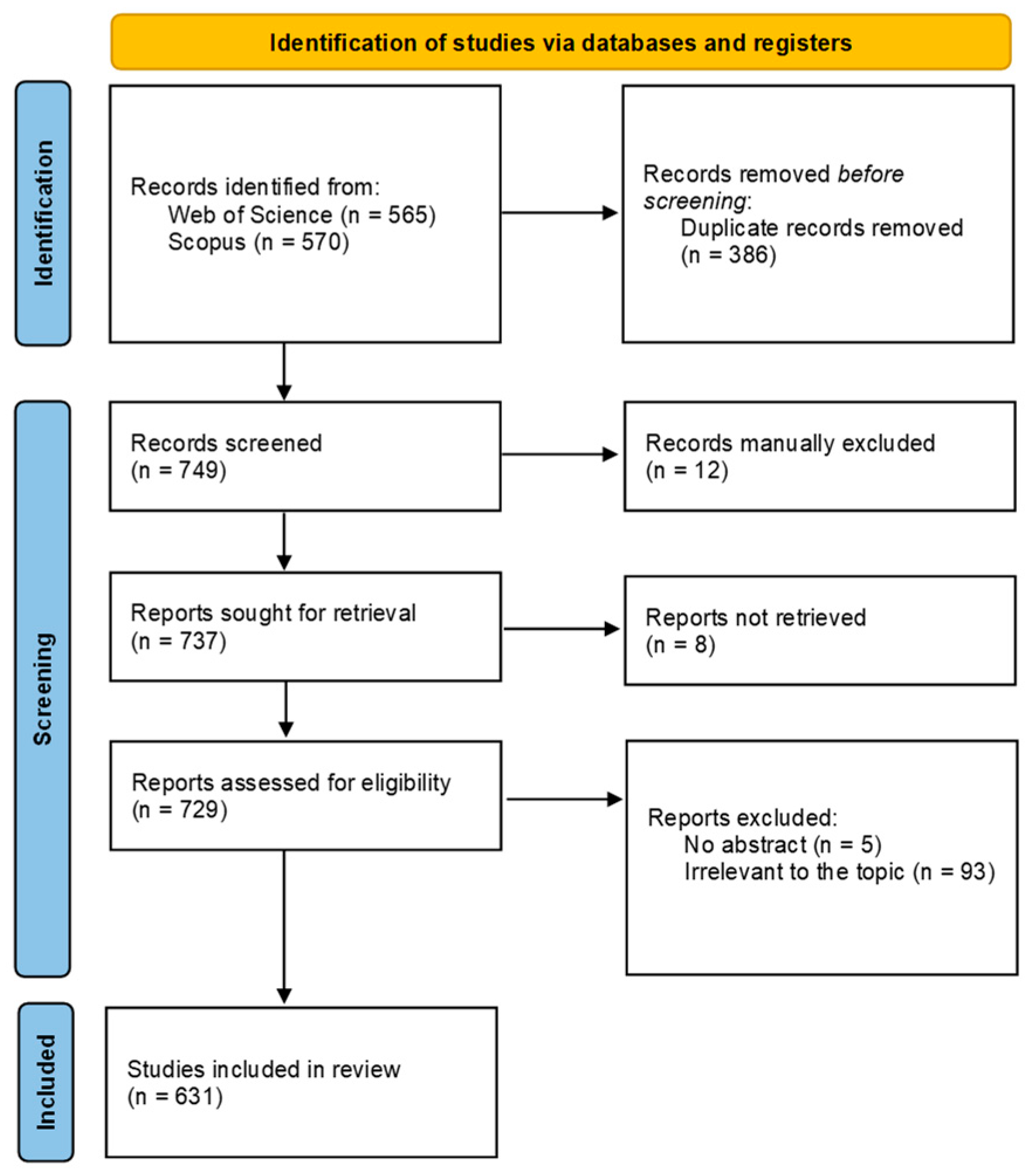

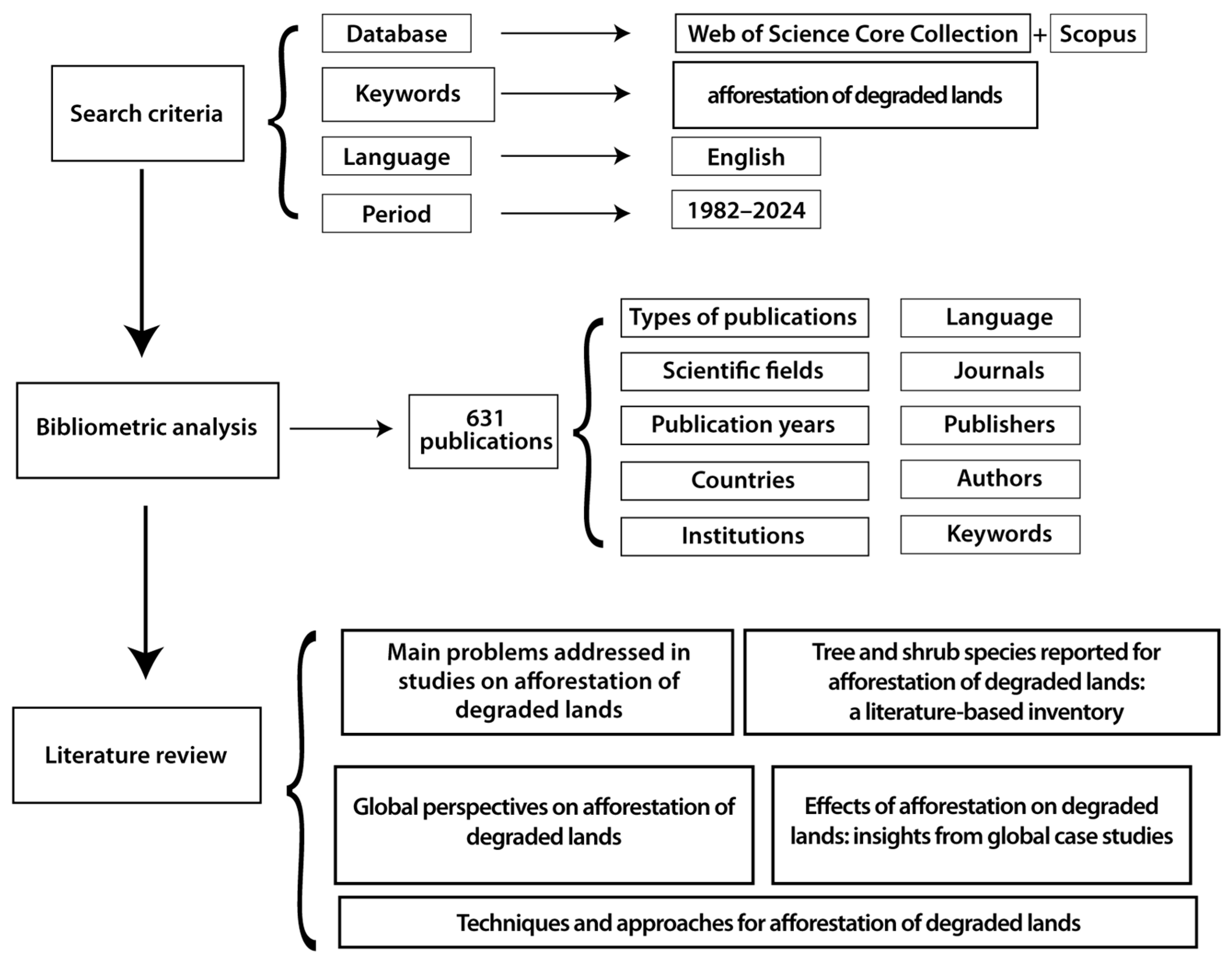

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

2.2. Traditional Literature Review

3. Results

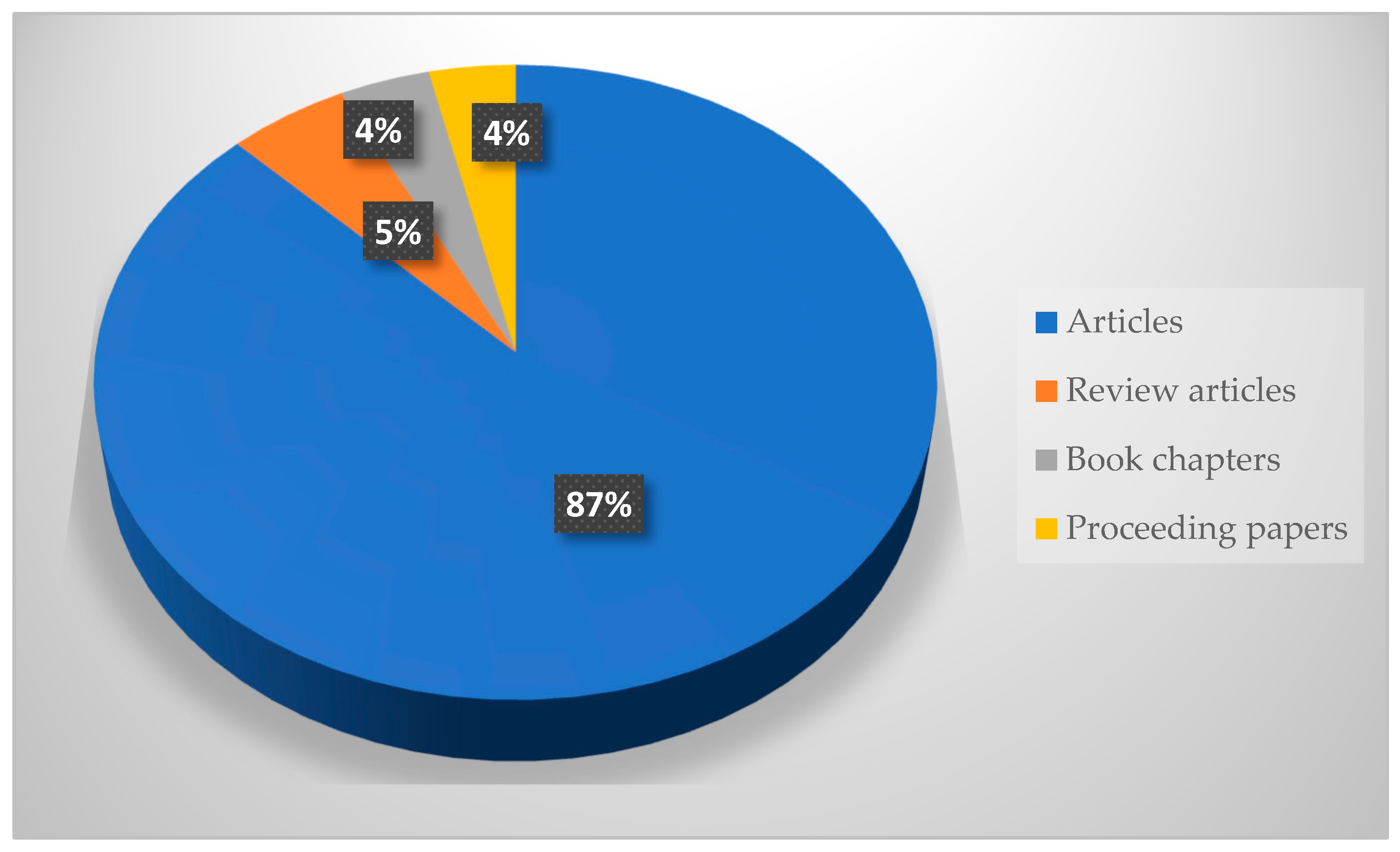

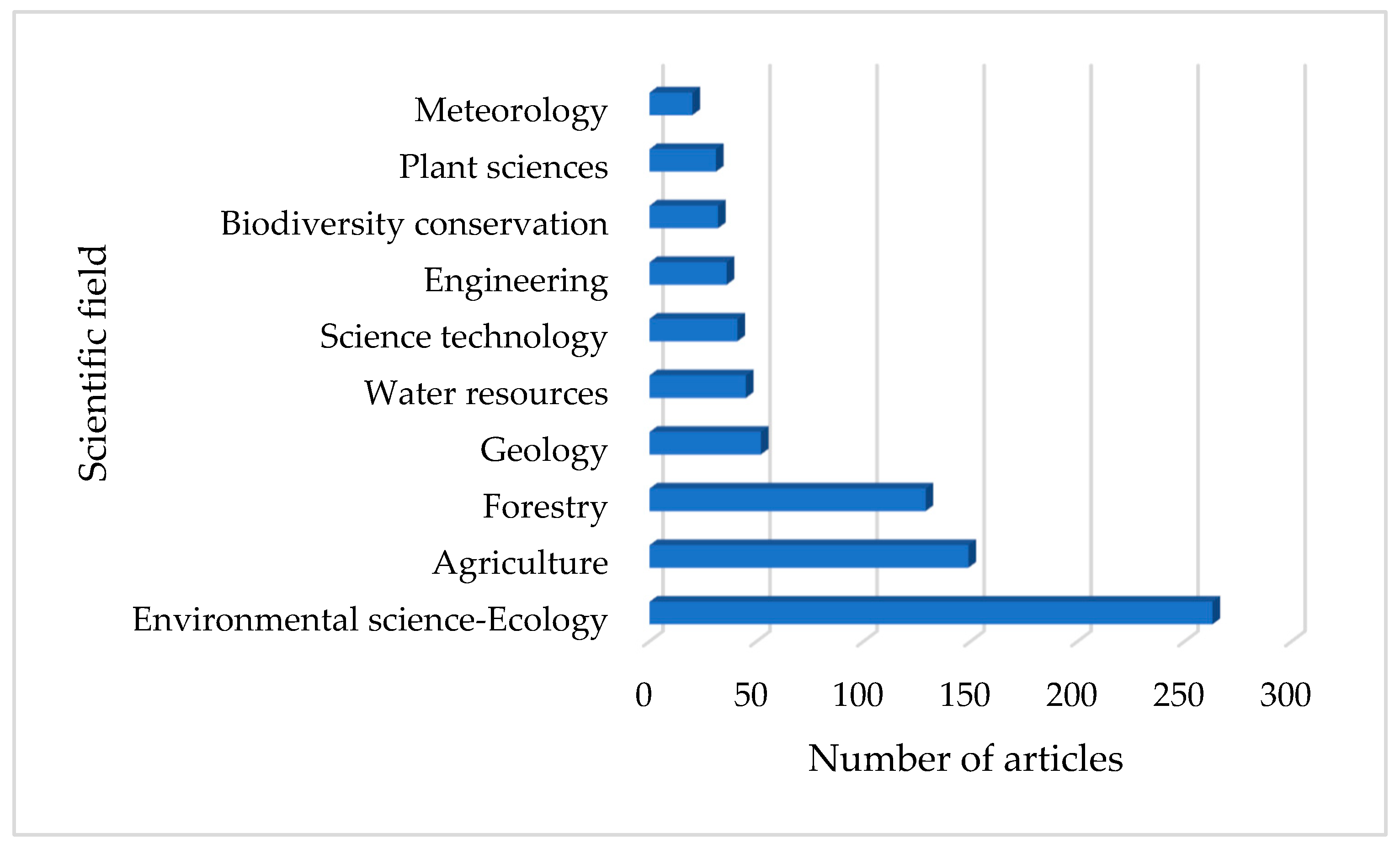

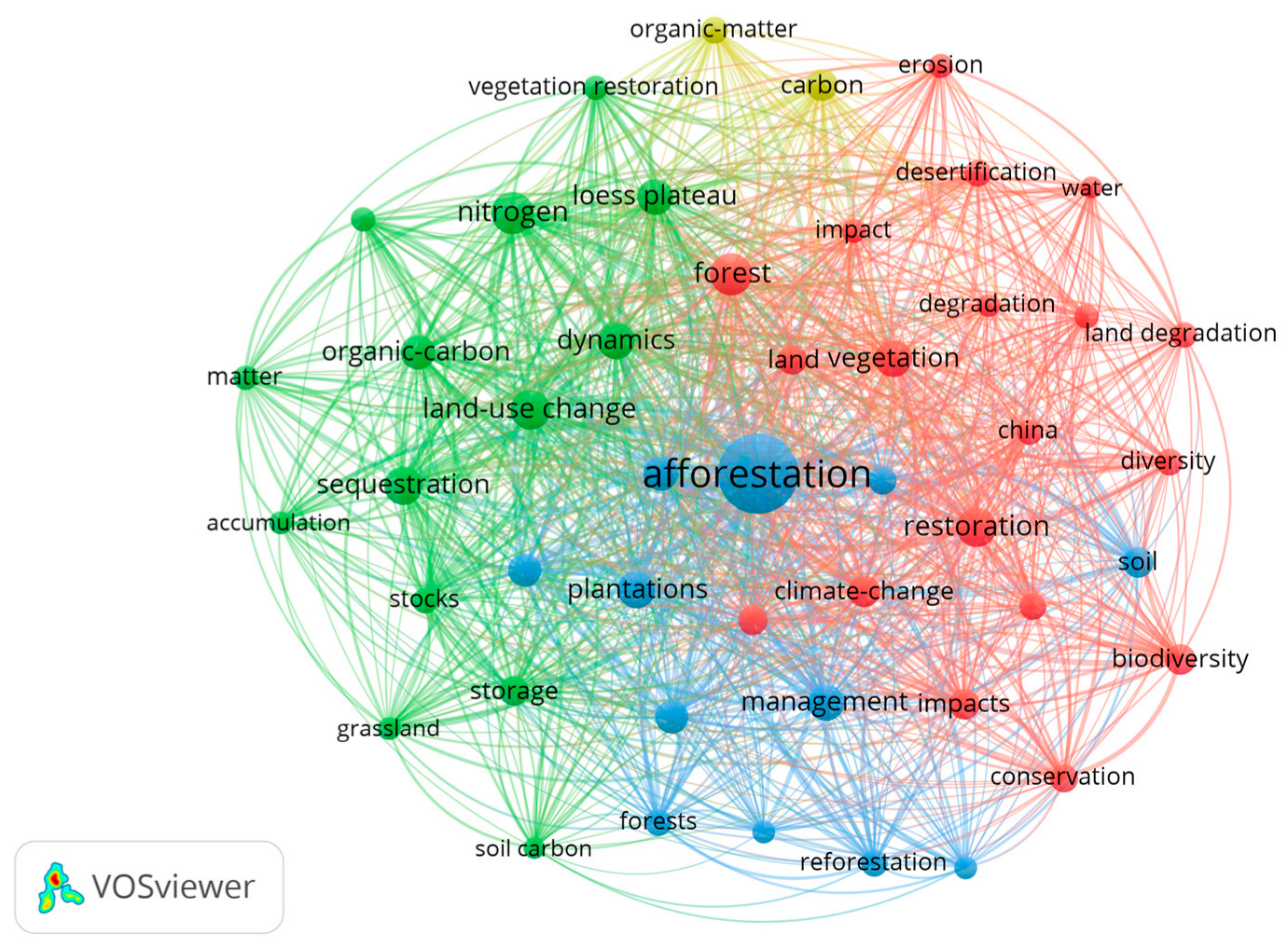

3.1. A Bibliometric Review

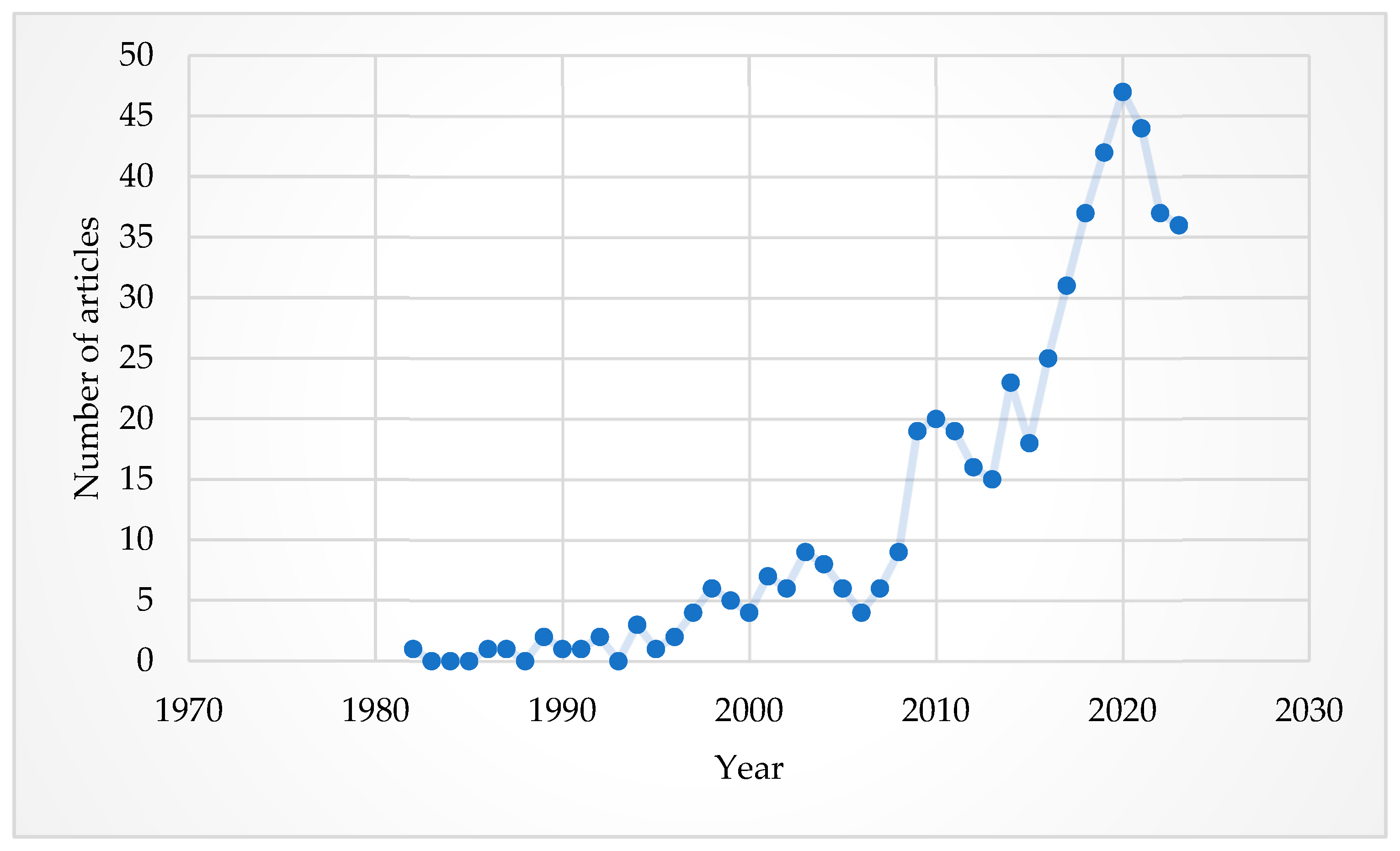

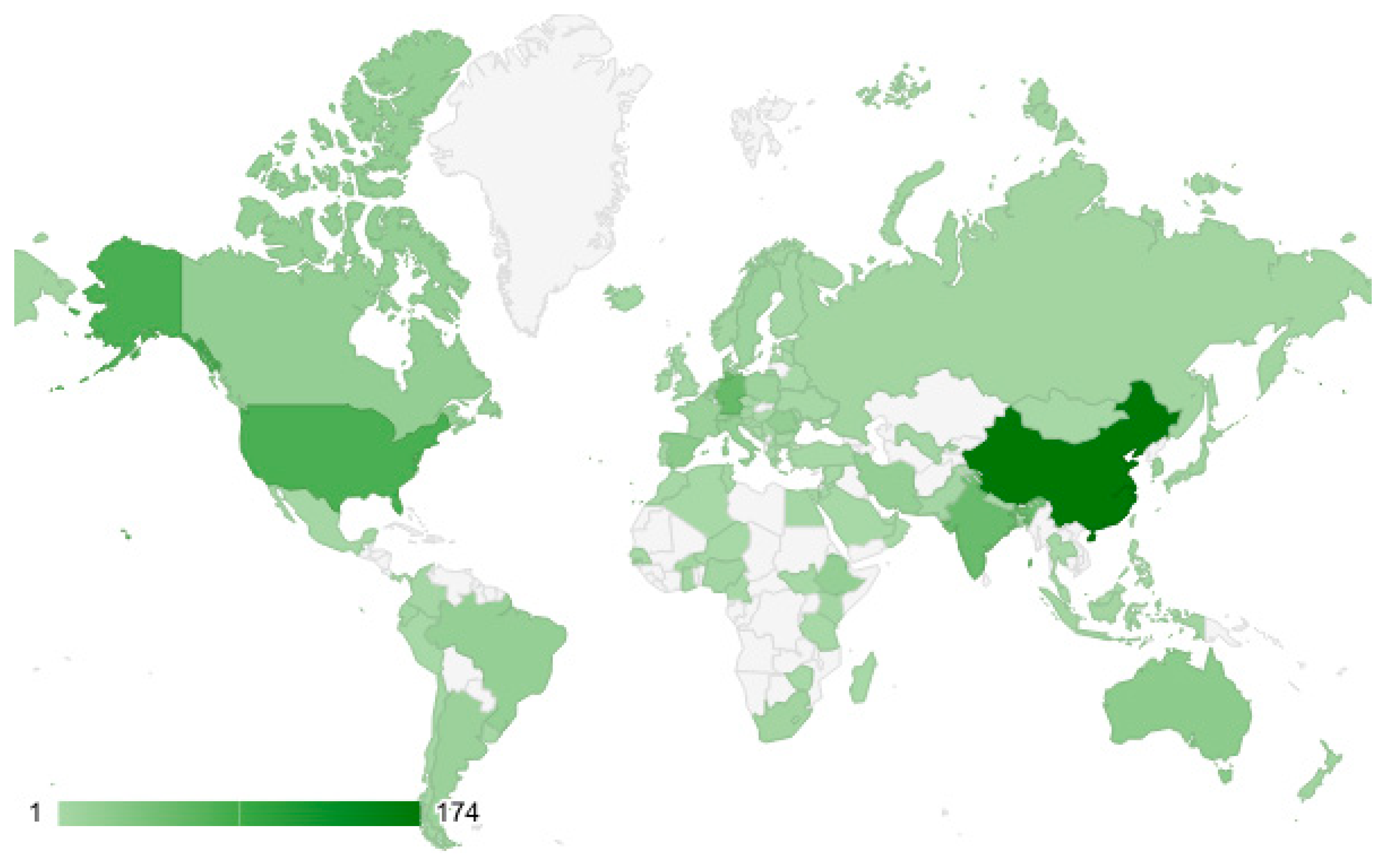

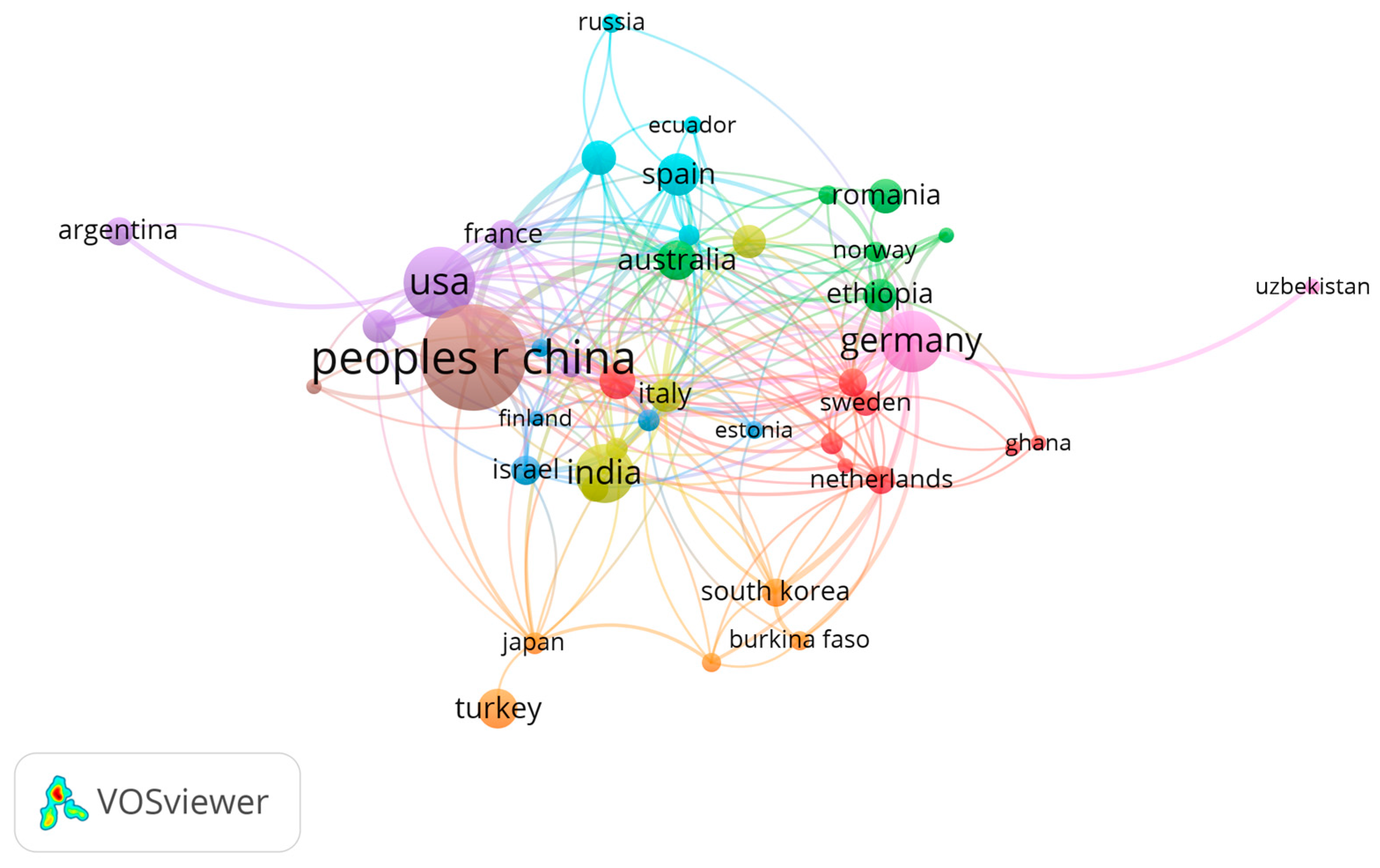

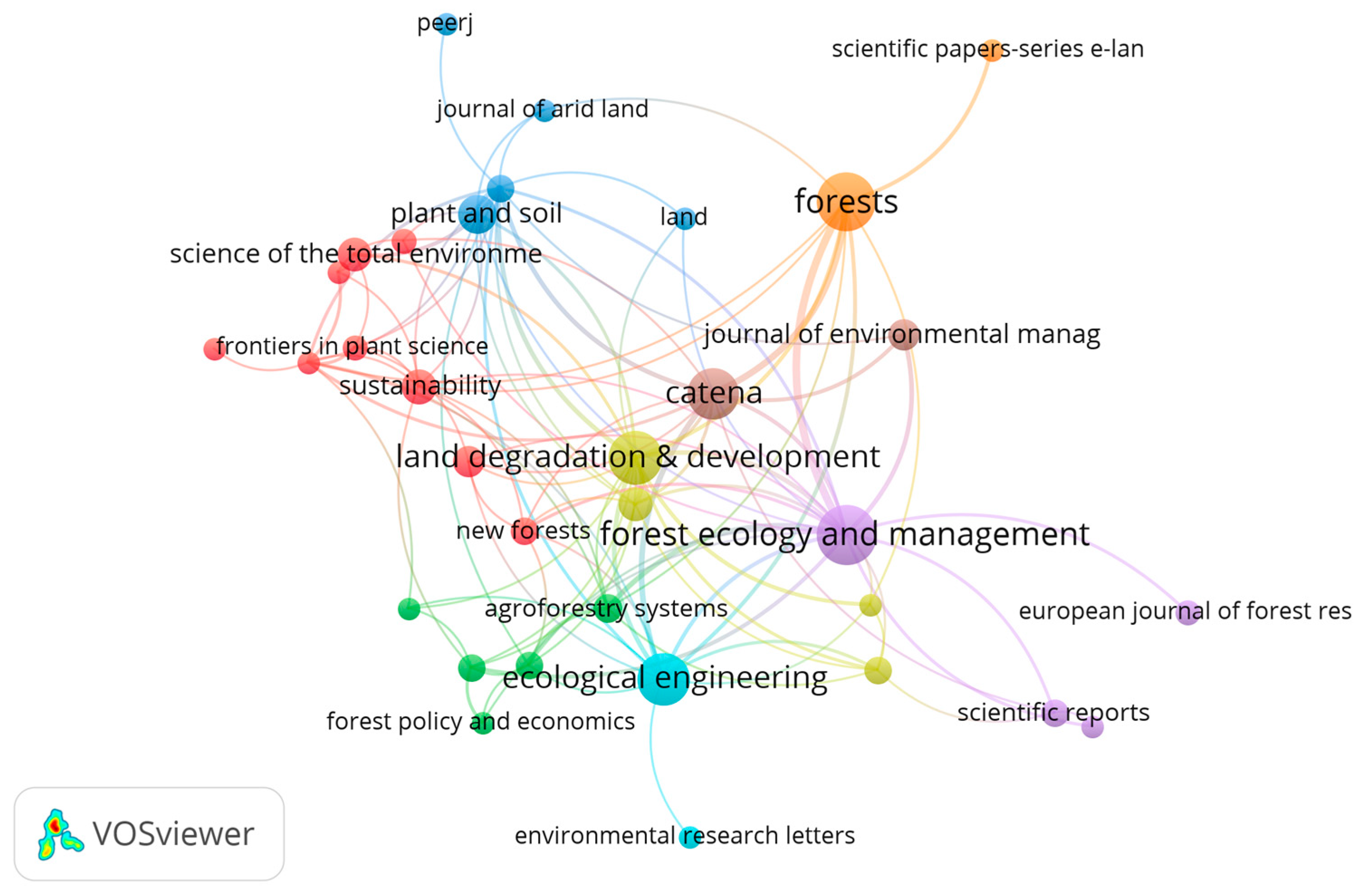

Temporal Evolution of Research Hotspots (1993–2024)

3.2. Literature Review

3.2.1. Main Problems Addressed in Studies on Afforestation of Degraded Lands

3.2.2. Tree and Shrub Species Reported for Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Literature-Based Inventory

3.2.3. Global Perspectives on Afforestation of Degraded Lands

3.2.4. Effects of Afforestation on Degraded Lands: Insights from Global Case Studies

3.2.5. Techniques and Approaches for Afforestation of Degraded Lands

3.2.6. Afforestation of Land Disturbed by Mining

Global Perspectives

Central European Experience: The “Black Triangle”

Soil Processes and Ecological Outcomes

Socio-Esthetic and Policy Dimensions

Synthesis

4. Discussion

4.1. Bibliometric Review

4.2. Critical Reflections on the Literature of Afforestation in Degraded Environments

4.3. Tree and Shrub Species Utilized for the Afforestation of Degraded Lands

4.3.1. Regional Specificity of Species Uses

4.3.2. Convergence on Certain Genera

4.3.3. Functional Traits and Tolerance to Stress

4.3.4. Multipurpose and Socio-Economic Roles

4.4. Patterns, Challenges, and Opportunities in Afforestation of Degraded Lands Across Regions

4.5. Balancing Benefits and Trade-Offs of Afforestation on Degraded Lands

4.5.1. Soil Fertility and Carbon Sequestration

4.5.2. Hydrological Outcomes: Gains and Risks

4.5.3. Biodiversity and Species Selection

4.5.4. Socio-Economic Considerations

4.5.5. Balancing the Trade-Offs

4.6. Ecological, Technical, and Policy Perspectives on Afforestation of Degraded Lands

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asnake, B. Land degradation and possible mitigation measures in Ethiopia: A review. J. Agric. Ext. Rural. Dev. 2024, 16, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temerdek-Ivan, K.; Benedek, J.; Török, I.; Holbâcă, I.H.; Alexe, M. Determination of Land Degradation in Romania at a Local Scale Using Advanced Analytical Techniques. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.G.; Dent, D.L.; Olsson, L.; Schaepman, M.E. Proxy global assessment of land degradation. Soil Use Manag. 2008, 24, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Nan, F.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, P.; Zhao, C. Effects of Different Afforestation Years on Soil Properties and Quality. Forests 2023, 14, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, F.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, L. The Long-Term Effects of Barren Land Afforestation on Plant Productivity, Soil Fertility, and Soil Moisture in China: A Meta-Analysis. Plants 2024, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, Z.; Han, Y.; Li, R.; Ni, J.; Wu, Z. Afforestation Influences Soil Aggregate Stability by Regulating Aggregate Transformation in Karst Rocky Desertification Areas. Forests 2023, 14, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; He, T.; Zhu, N.; Peng, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Dang, P. Effects of Afforestation Patterns on Soil Nutrient and Microbial Community Diversity in Rocky Desertification Areas. Forests 2023, 14, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongil-Manso, J.; Navarro-Hevia, J.; San Martin, R. Impact of Land Use Change and Afforestation on Soil Properties in a Mediterranean Mountain Area of Central Spain. Land 2022, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, H.; Li, E.; Yang, X. The Impact of Artificial Afforestation on the Soil Microbial Community and Function in Desertified Areas of NW China. Forests 2024, 15, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Ji, C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Liu, Q. The advantage of afforestation using native tree species to enhance soil quality in degraded forest ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Xie, H.; Zhang, G.; Qiao, F.; Geng, G.; Chongyi, E. Improvement Effects of Different Afforestation Measures on the Surface Soil of Alpine Sandy Land. Biology 2025, 14, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Wei, X.; Liu, X.; Shao, M. Long-term afforestation significantly improves the fertility of abandoned farmland along a soil clay gradient on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 3521–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psistaki, K.; Tsantopoulos, G.; Paschalidou, A.K. An Overview of the Role of Forests in Climate Change Mitigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Liu, E.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q. Afforestation inhibits aromatic ring cleavage and promotes soil organic carbon sequestration in seasonally flooded marshland soils at 1-m depth in China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 211, 106135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Fujimori, S.; Ito, A.; Takahashi, K. Careful selection of forest types in afforestation can increase carbon sequestration by 25% without compromising sustainability. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturday, A. Restoration of degraded agricultural land: A review. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2018, 4, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, M.V.; Stefanski, R. Climate and land degradation—An overview. In Climate and Land Degradation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 105–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lv, T. A bibliometric analysis on land degradation: Current status, development, and future directions. Land 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.; Murariu, G.; Lupoae, M. Understanding the ecosystem services of riparian forests: Patterns, gaps, and global trends. Forests 2025, 16, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, I.; Dincă, L.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G. Resilience and decline: The impact of climatic variability on temperate oak forests. Climate 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.; Crisan, V.; Ienășoiu, G.; Murariu, G.; Drăşovean, R. Environmental Indicator Plants in Mountain Forests: A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murariu, G.; Dincă, L.; Munteanu, D. Trends and Applications of Principal Component Analysis in Forestry Research: A Literature and Bibliometric Review. Forests 2025, 16, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, L. Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Review of Content and Searching Capabilities. Charlest. Advis. 2009, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate.com. Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-workflow-solutions/webofscience-platform/web-of-science-core-collection/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Elsevier. Scopus. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel?legRedir=true&CorrelationId=3bb60ab0-fe13-41a4-812b-2627667cf346 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Geochart. Available online: https://developers.google.com/chart/interactive/docs/gallery/geochart (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- VOSviewer. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 71, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, G.; Delang, C.O.; Lu, X. Afforestation changes soil organic carbon stocks on sloping land: The role of previous land cover and tree type. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 152, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akça, E.; Kapur, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Kaya, Z.; Bedestenci, H.C.; Yakti, S. Afforestation effect on soil quality of sand dunes. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, R.C.; Sharma, A. Afforestation for reclaiming degraded village common land: A case study. Biomass Bioenergy 2001, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Long, Q.; Huang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, N. Afforestation-induced large macroaggregate formation promotes soil organic carbon accumulation in degraded karst area. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Baez, S.E.; Domínguez-Haydar, Y.; Zwartendijk, B.W.; Cooper, M.; Tobón, C.; Di Prima, S. Contrasts in top soil infiltration processes for degraded vs. restored lands. A case study at the Perijá range in Colombia. Forests 2021, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneeva, E.A. Economic evaluation of ecological restoration of degraded lands through protective afforestation in the south of the Russian plain. Forests 2021, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, O.; Babur, E.; Altun, L.; Seyis, M. Effects of afforestation on microbial biomass C and respiration in eroded soils of Turkey. J. Sustain. For. 2016, 35, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.L.; Zeng, D.H.; Fan, Z.P.; Ai, G.Y. Effects of degraded sandy grassland afforestation on soil quality in semi-arid area of Northern China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 18, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Djalilov, B.M.; Khamzina, A.; Hornidge, A.K.; Lamers, J.P. Exploring constraints and incentives for the adoption of agroforestry practices on degraded cropland in Uzbekistan. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Duan, C. An evaluation of the sufficiency of natural soil seed banks to support vegetation restoration following severe soil degradation and heavy metal contamination. Plant Soil 2025, 513, 2745–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhou, X.; Dong, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Li, Q. Natural vegetation regeneration facilitated soil organic carbon sequestration and microbial community stability in the degraded karst ecosystem. Catena 2023, 222, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hbirkou, C.; Martius, C.; Khamzina, A.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Welp, G.; Amelung, W. Reducing topsoil salinity and raising carbon stocks through afforestation in Khorezm, Uzbekistan. J. Arid. Environ. 2011, 75, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helman, D.; Lensky, I.M.; Mussery, A.; Leu, S. Rehabilitating degraded drylands by creating woodland islets: Assessing long-term effects on aboveground productivity and soil fertility. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 195, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwal, J.; Pandey, V.C. Restoration of mine degraded land for sustainable environmental development. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassioumis, K.; Papageorgiou, K.; Christodoulou, A.; Blioumis, V.; Stamou, N.; Karameris, A. Rural development by afforestation in predominantly agricultural areas: Issues and challenges from two areas in Greece. For. Policy Econ. 2004, 6, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wen, M.; Geng, S.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J. Unfolding the effectiveness of ecological restoration programs in combating land degradation: Achievements, causes, and implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lintunen, A.; Zhao, P.; Shen, W.; Salmon, Y.; Chen, X.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, L.; Ni, G.; Sun, D.; et al. Assessing environmental control of sap flux of three tree species plantations in degraded hilly lands in South China. Forests 2020, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayen, P.; Lykke, A.M.; Thiombiano, A. Success of three soil restoration techniques on seedling survival and growth of three plant species in the Sahel of Burkina Faso (West Africa). J. For. Res. 2016, 27, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghverdi, K.; Kooch, Y. Long-term afforestation effect and help to optimize degraded forest lands and reducing climate changes. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 142, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bhatnagar, P.R.; Kakade, V.; Dobhal, S. Tree plantation and soil water conservation enhances climate resilience and carbon sequestration of agro ecosystem in semi-arid degraded ravine lands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 282, 107857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, C.M. Which woody species should be used for afforestation of household dumps consisting of demolition materials mixed with organic materials? Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2022, LXV, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Semwal, R.L.; Nautiyal, S.; Maikhuri, R.K.; Rao, K.S.; Saxena, K.G. Growth and carbon stocks of multipurpose tree species plantations in degraded lands in Central Himalaya, India. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 310, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noulèkoun, F.; Khamzina, A.; Naab, J.B.; Lamers, J.P. Biomass allocation in five semi-arid afforestation species is driven mainly by ontogeny rather than resource availability. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, F.D.; Gomes, L.C.; Castro, M.F.; Neves, J.C.L.; Silva, I.R.; de Oliveira, T.S. Influence of different tree species on autotrophic and heterotrophic soil respiration in a mined area under reclamation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4288–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Garg, V.K.; Katiyar, R.S. Tree species diversity and dominance in a man-made forest on sodic wasteland of North India. J. For. Res. 2004, 9, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekirstos, A.; Teketay, D.; Fetene, M.; Mitlöhner, R. Adaptation of five co-occurring tree and shrub species to water stress and its implication in restoration of degraded lands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 229, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, M.; Arnalds, O.; Kuhn, N.J. Evaluating the carbon sequestration potential of volcanic soils in southern Iceland after birch afforestation. Soil 2019, 5, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddsdóttir, E.S.; Nielsen, C.; Sen, R.; Harding, S.; Eilenberg, J.; Halldórsson, G. Distribution patterns of soil entomopathogenic and birch symbiotic ectomycorrhizal fungi across native woodland and degraded habitats in Iceland. Icel. Agric. Sci. 2010, 23, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Q.; Ma, Z.; An, Q.; Wu, G.L.; Chang, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, G. Does Caragana korshinskii plantation increase soil carbon continuously in a water-limited landscape on the Loess Plateau, China? Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; He, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Mo, Q. Divergent Effects of Monoculture and Mixed Plantation on the Trade-Off Between Soil Carbon and Phosphorus Contents in a Degraded Hilly Land. Forests 2024, 15, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colișar, A.; Dîrja, M.; Simonca, V.; Sîngeorzan, S.M.; Sfeclă, V.; Vlasin, H.D.; Negrusier, C.; Truta, A.M.; Rebrean, F.A.; Ceuca, V. Sustainability of some forest species associations established on degraded lands from the Transylvania Plain, in the context of climate change. Sci. Pap. Ser. E Land Reclam. Earth Obs. Surv. Environ. Eng. 2024, 13, 937–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lemenih, M.; Olsson, M.; Karltun, E. Comparison of soil attributes under Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus saligna established on abandoned farmlands with continuously cropped farmlands and natural forest in Ethiopia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 195, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djumaeva, D.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Khamzina, A.; Vlek, P.L.G. The benefits of phosphorus fertilization of trees grown on salinized croplands in the lower reaches of Amu Darya, Uzbekistan. Agrofor. Syst. 2013, 87, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovyk, O.; Menz, G.; Khamzina, A. Land suitability assessment for afforestation with Elaeagnus angustifolia L. In degraded agricultural areas of the lower Amurdarya river basin. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulmane, M.; Oubrahim, H.; Halim, M.; Bakker, M.R.; Augusto, L. The potential of Eucalyptus plantations to restore degraded soils in semi-arid Morocco (NW Africa). Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.E.; Esparrach, C.A.; Galetti, M.A.; Wall, L.G. Afforestation of a desurfaced field with Robinia pseudoacacia inoculated with Rhizobium spp. and Glomus deserticola. Cienc. Suelo 2010, 28, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Constandache, C.; Peticilă, A.; Dincă, L.; Vasile, D. The usage of Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) for improving Romania’s degraded lands. AgroLife Sci. J. 2016, 5, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kagambèga, F.W.; Thiombiano, A.; Traoré, S.; Zougmoré, R.; Boussim, J.I. Survival and growth responses of Jatropha curcas L. to three restoration techniques on degraded soils in Burkina Faso. Ann. For. Res. 2011, 54, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dato, G.D.; Loperfido, L.; De Angelis, P.; Valentini, R. Establishment of a planted field with Mediterranean shrubs in Sardinia and its evaluation for climate mitigation and to combat desertification in semi-arid regions. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2009, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Ghasemi, M.; Jafarzadeh, A. Determination of suitable areas for reforestation and afforestation with indigenous species. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 15, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpana Mishra, K.M. Calcium deficiency effects in Leucaena leucocephala Lam. de Wit. seedlings suitable for afforestation in degraded lands of Uttar Pradesh. Indian For. 2001, 127, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Lu, Y.; Luo, L.; Tao, L.; Xiao, T.; Liu, Y. The Carbon Storage of Reforestation Plantings on Degraded Lands of the Red Soil Region, Jiangxi Province, China. Forests 2024, 15, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, T.; Milne, E. Carbon storage in a wolfberry plantation chronosequence established on a secondary saline land in an arid irrigated area of Gansu Province, China. J. Arid Land 2018, 10, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoohestani, G.; Salehi Mourkani, M.; Zare, S.; Rafie, H.; Farahat, E.A.; Sardari, F.; Asadi, A. Improving the livelihoods of local communities in degraded desert regions through afforestation with Moringa peregrina trees to combat desertification. J. Arid Land 2025, 17, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtsiek, T.; Lamers, J.P.; Khamzina, A. Early survival and growth of six afforestation species on abandoned cropping sites in irrigated drylands of the Aral Sea Basin. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2014, 28, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglioli, P.A.; Alvarez, J.A.; Lana, N.B.; Cony, M.A.; Villagra, P.E. Salt tolerance of native trees relevant to the restoration of degraded landscapes in the Monte region, Argentina. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fataei, E.; Varamesh, S.; Safavian, S.T.S. Microbiological pools of soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus under exotic tree plantations in the degraded grasslands of Iran. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 9, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar]

- Omary, A.A. Effects of aspect and slope position on growth and nutritional status of planted Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) in a degraded land semi-arid area of Jordan. New For. 2011, 42, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirino, E.; Bonet, A.; Bellot, J.; Sánchez, J.R. Effects of 30-year-old Aleppo pine plantations on runoff, soil erosion, and plant diversity in a semi-arid landscape in southeastern Spain. Catena 2006, 65, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, H. Effects of rehabilitation through afforestation on soil aggregate stability and aggregate-associated carbon after forest fires in subtropical China. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiyeoba, I.A. Soil rehabilitation through afforestation: Evaluation of the performance of Eucalyptus and pine plantations in a Nigerian Savanna environment. Land Degrad. Dev. 2001, 12, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, L.; Tarabini, M.; Gomez, F.; Rostagno, C.M. Changes in soil organic matter associated with afforestation affect erosion processes: The case of erodible volcanic soils from Patagonia. Geoderma 2021, 403, 115265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constandache, C.; Tudor, C.; Vlad, R.; Dincă, L.; Popovici, L. The productivity of pine stands on degraded lands. Sci. Pap. Ser. E Land Reclam. Earth Obs. Surv. Environ. Eng. 2021, 10, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestru-Grigore, C.V.; Dinulică, F.; Spârchez, G.; Hălălișan, A.F.; Dincă, L.C.; Enescu, R.E.; Crișan, V.E. Radial growth behavior of pines on Romanian degraded lands. Forests 2018, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.; Constandache, C.; Dinca, L.; Tudose, N.C.; Sidor, C.G.; Popovici, L.; Ispravnic, A. Influence of climatic, site and stand characteristics on some structural parameters of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forests situated on degraded lands from east Romania. Range Manag. Agrofor. 2019, 40, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, W.; Wu, P. Identifying a suitable revegetation technique for soil restoration on water-limited and degraded land: Considering both deep soil moisture deficit and soil organic carbon sequestration. Geoderma 2018, 319, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, J.P.A.; Martius, C.; Khamzina, A.; Matkarimova, M.; Djumaeva, D.; Eshchanov, R. Green foliage decomposition in tree plantations on degraded, irrigated croplands in Uzbekistan, Central Asia. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 2010, 87, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyam-Osor, B.; Byambadorj, S.O.; Park, B.B.; Terzaghi, M.; Scippa, G.S.; Stanturf, J.A.; Chiatante, D.; Montagnoli, A. Root biomass distribution of Populus sibirica and Ulmus pumila afforestation stands is affected by watering regimes and fertilization in the Mongolian semi-arid steppe. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 638828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchuk, A.H.; Díaz, M.P.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Karlin, U.O. Experimental study on survival rates in two arboreal species from the Argentinean Dry Chaco. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 103, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwal, J.; Maiti, S.K.; Reddy, M.S. Development of carbon, nitrogen and phosphate stocks of reclaimed coal mine soil within 8 years after forestation with Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) Dc. Catena 2017, 156, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojvaid, P.P.; Timmer, V.R.; Singh, G. Reclaiming sodic soils for wheat production by Prosopis juliflora (Swartz) DC afforestation in India. Agrofor. Syst. 1996, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljasmi, M.; El-Keblawy, A.; Mosa, K.A. Abiotic factors controlling germination of the multipurpose invasive Prosopis pallida: Towards afforestation of salt-affected lands in the subtropical arid Arabian desert. Trop. Ecol. 2021, 62, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamzina, A.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Worbes, M.; Botman, E.; Vlek, P.L. Assessing the potential of trees for afforestation of degraded landscapes in the Aral Sea Basin of Uzbekistan. Agrofor. Syst. 2006, 66, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, V. Almond plantations in bare-degraded forest and treasure lands: Achievements and failures. VI Int. Symp. Almonds Pist. 2013, 1028, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M.C.; Mazza, G.; Papini, L.; Pelleri, F. Effects of mixture and management on growth dynamics and responses to climate of Quercus robur L. in a restored opencast lignite mine. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2022, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constandache, C.; Dincă, L.; Tudor, C. The bioproductive potential of fast-growing forest species on degraded lands. Sci. Pap. Ser. E Land Reclam. Earth Obs. Surv. Environ. Eng. 2020, 9, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuvăț, A.L.; Abrudan, I.V.; Ciuvăț, C.G.; Marcu, C.; Lorent, A.; Dincă, L.; Szilard, B. Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) in Romanian Forestry. Diversity 2022, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, C.M. Sandy soils from Oltenia and Carei Plains: A problem or an opportunity to increase the forest fund in Romania? Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 19, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Afreen, S.; Sharma, N.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Ravindranath, N.H. Forest policies and programs affecting vulnerability and adaptation to climate change. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2011, 16, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Parrotta, J.A.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Karlen, D.L.; Vieira, D.L.M.; Anker, Y.; Chen, R.; Morris, J.; Harris, J.; Ntshotsho, P. A framework to evaluate land degradation and restoration responses for improved planning and decision-making. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanLanh, L. Establishment of ecological models for rehabilitation of degraded barren midland land in northern Vietnam. J. Trop. For. Sci. 1994, 7, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Çaliskan, S.; Boydak, M. Afforestation of arid and semiarid ecosystems in Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2017, 41, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbulak, F.; Erdoğan, B.U.; Yıldırım, H.T.; Özçelik, M.S. Causes of land degradation and rehabilitation efforts of rangelands in Turkey. Forestist 2018, 68, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Enescu, C.M. Allochthonous tree species used for afforestation of salt-affected soils in Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2020, 63, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Enescu, C.M.; Caradaică, M. Which woody species are preferred in the composition pf agroforestry systems in sandy soils of Dolj County? Ann. Univ. Craiova—Agric. Mont. Cadastre Ser. 2023, 53, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Raspopina, S.P.; Vedmid, M.M.; Bila, Y.M.; Horoshko, V.V. The state and main problems of afforestation in Ukraine. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2019, 10, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runólfsson, S.; Ágústsdóttir, A.M. Restoration of degraded and desertified lands: Experience from Iceland. In Climate Change and Food Security in South Asia; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- El Mangouri, H. Dryland management in the Kordofan and Darfur Provinces of Sudan. In Dryland Management: Economic Case Studies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamoga, G.Z.; Sjølie, H.K.; Malimbwi, R.; Ngaga, Y.M.; Solberg, B. Potentials for rehabilitating degraded land in Tanzania. In Climate Change and Multi-Dimensional Sustainability in African Agriculture: Climate Change and Sustainability in Agriculture; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pistorius, T.; Carodenuto, S.; Wathum, G. Implementing forest landscape restoration in Ethiopia. Forests 2017, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, N.; Palomeque, X.; Weber, M.; Stimm, B.; Günter, S. Reforestation and natural succession as tools for restoration on abandoned pastures in the Andes of South Ecuador. In Silviculture in the Tropics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 513–524. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Kim, S.; Chang, H.; Khamzina, A.; Son, Y. Vegetation establishment improves topsoil properties and enzyme activities in the dry Aral Sea Bed, Kazakhstan. J. Fac. For. Istanb. Univ. 2018, 68, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Tokuchi, N. Soil organic carbon accumulation following afforestation in a Japanese coniferous plantation based on particle-size fractionation and stable isotope analysis. Geoderma 2010, 159, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, A.M.; Brouwer, L.C. The effect of afforestation as a restoration measure in a degraded area in a Mediterranean environment near Lorca (Spain). WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2025, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hai, X.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Shangguan, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, L. Forestation delivers significantly more effective results in soil C and N sequestrations than natural succession on badly degraded areas: Evidence from the Central Loess Plateau case. Catena 2022, 208, 105734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Li, J.Y.; Wan, W.; Zhang, R.Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.G. Response of soil aggregate-associated fertility and microbial communities to afforestation in the degraded ecosystem of the Danjiangkou Reservoir, China. Plant Soil 2024, 501, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, X. Impact of China’s Grain for Green Project on the landscape of vulnerable arid and semi-arid agricultural regions: A case study in northern Shaanxi Province. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duponnois, R.; Baudoin, E.; Sanguin, H.; Thioulouse, J.; Roux, C.L.; Tournier, E.; Galiana, Y.; Prin, Y.; Dreyfus, B. Australian acacia introduction to rehabilitate degraded ecosystems is it free of environmental risks? Bois Forêt Trop. 2013, 318, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, I.R.; Hobley, M.; Smale, P. Afforestation of degraded land—Pyrrhic victory over economic, social and ecological reality? Ecol. Eng. 1998, 10, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraon, P.R.; Sagar, V.; Beauty, K. Ecological restoration of degraded land through afforestation activities. In Land and Environmental Management Through Forestry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parandiyal, A.K.; Kaushal, R.; Chaturvedi, O.P. Forest and fruit trees-based agroforestry systems for productive utilization of ravine lands. In Ravine Lands: Greening for Livelihood and Environmental Security; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 361–383. [Google Scholar]

- Caravaca, F.; Figueroa, D.; Alguacil, M.M.; Roldán, A. Application of composted urban residue enhanced the performance of afforested shrub species in a degraded semiarid land. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 90, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinger, D.; Kaushal, R.; Kumar, R.; Paramesh, V.; Verma, A.; Shukla, M.; Chavan, S.B.; Kakade, V.; Dobhal, S.; Uthappa, A.R.; et al. Degraded land rehabilitation through agroforestry in India: Achievements, current understanding, and future prospectives. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1088796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, O.P.; Kaushal, R.; Tomar, J.M.S.; Prandiyal, A.K.; Panwar, P. Agroforestry for wasteland rehabilitation: Mined, ravine, and degraded watershed areas. In Agroforestry Systems in India: Livelihood Security & Ecosystem Services; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 233–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir, B.; Tiwari, R. Role of Biotechnology in Afforestation and Land. Technol. A Sustain. Environ. 2023, 3, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Stavi, I.; Fizik, E.; Argaman, E. Contour bench terrace (shich/shikim) forestry systems in the semi-arid Israeli Negev: Effects on soil quality, geodiversity, and herbaceous vegetation. Geomorphology 2015, 231, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Pranto, M.A.; Shabab, M.R.; Rone, M.R.I.; Al Miraj, M.A.; Hossen, M.M.; Shoumi, S. Revitalizing the Land: Ecosystem Restoration in Post-Mining Areas. N. Am. Acad. Res. 2024, 7, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.K.; Pachu, A.V.; Jeeva, V.; Rao, N.R.; Sekhar, A.; Singh, A.N.; Kumar, S. Enhancing Sustainability: Reclamation and Rehabilitation Strategies for Restoring Mined-Out Lands in India to Mitigate Climate Change Impacts. In Forests and Climate Change: Biological Perspectives on Impact, Adaptation, and Mitigation Strategies; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 573–603. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, T.; Du, H.; Guo, P.; Wang, S.; Ma, M. Research progress in the joint remediation of plants–microbes–soil for heavy metal-contaminated soil in mining areas: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Tang, N.; Li, H.; Corti, G.; Jiang, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Wu, Z.; Feng, C.; et al. Long-term effects of phytoextraction by a poplar clone on the concentration, fractionation, and transportation of heavy metals in mine tailings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 47528–47539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J.; Pižl, V.; Tajovský, K.; Starý, J.; Holec, M.; Materna, J. Soil macro-and mesofauna succession in post-mining sites and other disturbed areas. In Soil Biota and Ecosystem Development in Post Mining Sites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Vindušková, O.; Frouz, J. Soil carbon accumulation after open-cast coal and oil shale mining in Northern Hemisphere: A quantitative review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, M. Tree species selection and reaction to mine soil reconstructed at reforested post-mine sites: Central and eastern European experiences. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 142, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulias, R. Upper Silesian Region—An example of large-scale transformation of relief by mining. In Landscapes and Landforms of Poland; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hełdak, M.; Lipsa, J.; Pokładek, R. Environmental effects of coal mine closures in the Lower Silesian Coal Basin, Poland. J. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 26, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttl, R.F.; Weber, E. Forest ecosystem development in post-mining landscapes: A case study of the Lusatian lignite district. Naturwissenschaften 2001, 88, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensa, O.; Hüttlb, R.F. Soil Properties and Development of Humus Forms in Pine and Oak Stands of Reclaimed Post-mining Sites in Lusatia. Soil Biota Ecosyst. Dev. Post Min. Sites 2013, 5, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Spasić, M.; Vacek, O.; Vejvodová, K.; Borůvka, L.; Tejnecký, V.; Drábek, O. Profile development and soil properties of three forest reclamations of different ages in Sokolov mining basin, Czech Republic. Forests 2024, 15, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Kohlová, M.; Nepožitková, P.; Melichar, J. How do observable characteristics of post-mining forests affect their attractiveness for recreation? Land 2021, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Peña-Arancibia, J.L.; Sheil, D.; Ziegler, A.D.; Zhang, J.; Zwartendijk, B.W.; Birkel, C.; Sun, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Potential for improved groundwater recharge and dry-season flows through Forest Landscape Restoration on degraded lands in the tropics. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 14, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L.; Marin, D.I. Romanian soil resources—“Healthy soils for a healthy life”. AgroLife Sci. J. 2015, 4, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, V.M.; Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L. The effect of applying some materials from the metallurgical industry on agricultural crops. AgroLife Sci. J. 2023, 12, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crt. No. | Journal | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Forest Ecology and Management | 29 | 2006 | 54 |

| 2 | Land Degradation and Development | 23 | 482 | 37 |

| 3 | Catena | 21 | 979 | 34 |

| 4 | Forests | 28 | 442 | 33 |

| 5 | Ecological Engineering | 22 | 843 | 27 |

| 6 | Geoderma | 9 | 378 | 14 |

| 7 | Agroforestry systems | 7 | 173 | 13 |

| 8 | Plant and Soil | 12 | 456 | 10 |

| 9 | Sustainability | 10 | 167 | 10 |

| 10 | Journal of Environmental Management | 8 | 61 | 8 |

| 11 | New Forests | 6 | 213 | 8 |

| 12 | Science of the Total Environment | 9 | 287 | 7 |

| 13 | Restoration Ecology | 8 | 884 | 6 |

| 14 | Scientific Reports | 6 | 172 | 5 |

| Crt. No. | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | afforestation | 258 | 930 |

| 2 | nitrogen | 72 | 343 |

| 3 | sequestration | 59 | 299 |

| 4 | forest | 72 | 286 |

| 5 | land-use change | 63 | 265 |

| 6 | loess plateau | 54 | 263 |

| 7 | dynamics | 55 | 249 |

| 8 | plantations | 56 | 244 |

| 9 | restoration | 64 | 238 |

| 10 | organic carbon | 50 | 231 |

| 11 | vegetation | 55 | 223 |

| 12 | biomass | 47 | 202 |

| Cur. No. | Analyzed Issue | Country | Citing Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Afforestation changes soil organic carbon stocks on sloping land | China | Hou et al., 2020 [30] |

| 2 | Afforestation effect on soil quality of sand dunes | Turkey | Akca et al., 2010 [31] |

| 3 | Afforestation for reclaiming degraded village common land | India | Pal and Sharma, 2001 [32] |

| 4 | Afforestation-induced large macroaggregate formation promotes soil organic carbon accumulation in degraded karst area | China | Lan et al., 2022 [33] |

| 5 | Contrasts in topsoil infiltration processes for degraded vs. restored lands | Colombia | Lozano-Baez et al., 2021 [34] |

| 6 | Economic evaluation of ecological restoration of degraded lands through protective afforestation | Russia | Korneeva, 2021 [35] |

| 7 | Effects of afforestation on microbial biomass C and respiration in eroded soils | Turkey | Kara et al., 2016 [36] |

| 8 | Effects of degraded sandy grassland afforestation on soil quality | China | Hu et al., 2007 [37] |

| 9 | Exploring constraints and incentives for the adoption of agroforestry practices on degraded lands | Uzbekistan | Djalilov et al., 2014 [38] |

| 10 | Natural soil seed banks support vegetation restoration following severe soil degradation and heavy metal contamination | China | Li et al., 2025 [39] |

| 11 | Natural vegetation regeneration facilitated soil organic carbon sequestration and microbial community stability in the degraded karst ecosystem | China | Cheng et al., 2023 [40] |

| 12 | Reducing topsoil salinity and raising carbon stocks through afforestation | Uzbekistan | Hbirkou et al., 2011 [41] |

| 13 | Rehabilitating degraded drylands by creating woodland islets | Israel | Helman et al., 2014 [42] |

| 14 | Restoration of mine degraded land | India | Ahirwal et al., 2021 [43] |

| 15 | Rural development by afforestation in predominantly agricultural degraded areas | Greece | Kassioumis et al., 2004 [44] |

| 16 | Unfolding the effectiveness of ecological restoration programs in combating land degradation: Achievements, causes, and implications | China | Jiang et al., 2020 [45] |

| Cur. No. | Tree Species | Land Category | Country | Citing Article | Origin (Relative to Country) | Functional/Ecological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acacia mangium Willd. | Degraded hilly land | China | Wang et al., 2020 [46] | Exotic (native to Australia/New Guinea) | Nitrogen-fixing legume; fast-growing pioneer; soil fertility restoration |

| 2 | Acacia nilotica (L.) P.J.H.Hurter & Mabb | degraded land in a Sahelian ecosystem | Burkina Faso | Bayen et al., 2016 [47] | Native (Sahel/Africa & S Asia) | Nitrogen-fixing; drought-tolerant; soil stabilizer; multipurpose (fodder, fuel) |

| 3 | Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Galasso & Banfi | degraded land in a Sahelian ecosystem | Burkina Faso | Bayen et al., 2016 [47] | Native (Sahel/NE Africa) | Drought-tolerant pioneer; soil stabilizer; browse/fodder |

| 4 | Acer velutinum Bioss. | Degraded land | Iran | Haghverdi and Kooch, 2020 [48] | Native (Caucasus/N Iran) | Native broadleaf; mid-successional timber/biodiversity facilitator |

| 5 | Achras zapota (L.) P.Royen | agro ecosystem in semi-arid degraded ravine lands | India | Kumar et al., 2020 [49] | Exotic (native to Mesoamerica) | Fruit tree/multipurpose; drought-tolerant when established; soil cover and livelihood value |

| 6 | Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | Household dumps | Romania | Enescu et al., 2022 [50] | Exotic (native to China) | Pioneer, fast-growing colonizer; tolerant of disturbed sites (often invasive) |

| 7 | Albizia lebeck (L.) Benth. | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (South & SE Asia) | Nitrogen-fixing legume; fast-growing, soil amelioration; shade/fodder |

| 8 | Alnus nepalensis D. Don | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (Himalayan region) | Nitrogen-fixing; pioneer on degraded, moist slopes; stabilizer |

| 9 | Alnus subcordata C.A.Mey | Degraded land | Iran | Haghverdi and Kooch, 2020 [48] | Native (Caucasus/N Iran) | Nitrogen-fixing; riparian/upland stabilizer; pioneer |

| 10 | Anacardium occidentale L. | Degraded semi-arid land | Burkina Faso | Noulekoun et al., 2017 [52] | Exotic (native to NE Brazil) | Fruit/multipurpose; agroforestry species that provides income and canopy cover |

| 11 | Anadenanthera peregrina L. | Mined area under reclamation | Brazil | Valente et al., 2021 [53] | Native (Neotropics; Brazil) | Nitrogen-fixing legume; pioneer; soil improvement in reclamation |

| 12 | Azadirachta indica A.Juss. | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native (Indian subcontinent/Myanmar) | Multipurpose (soil amelioration, pest-resistant, medicinal); tolerant to poor soils |

| 13 | Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile | Deforested savanna | Ethiopia | Gebrekirstos et al., 2006 [55] | Native (Sahel/Africa) | Drought-tolerant; soil stabilizer; multipurpose (fruit, fuel) |

| 14 | Betula pendula Roth. | Degraded lands | Iceland | Hunziker et al., 2019 [56] | Native (Europe) | Early successional broadleaf; soil stabilization and biodiversity support |

| 15 | Betula pubescens Ehrh. | Degraded habitats | Iceland | Oddsdottir et al., 2010 [57] | Native (Northern Europe) | Pioneer tree for degraded northern sites; soil stabilizer |

| 16 | Caragana korshinskii Kom. | semiarid areas | China | Chai et al., 2019 [58] | Native (north-west China/Mongolia) | Nitrogen-fixing shrubs; windbreak; erosion control; drought-tolerant |

| 17 | Castanopsis hystrix A.DC. | degraded hilly land | China | Gu et al., 2024 [59] | Native (S & SE Asia; parts of China) | Mid-successional timber species; biodiversity/canopy restoration |

| 18 | Celtis australis L. | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Generally native to Mediterranean/SW Asia | Multipurpose shade/soil stabilizer; wildlife food tree |

| 19 | Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Degraded lands | Romania | Colișar et al., 2024 [60] | Native (Europe) | Shrub/tree pioneer; supports biodiversity; stabilizer on marginal land |

| 20 | Cupressus lusitanica (Mill.) Bartel | abandoned farmlands | Ethiopia | Lemenih et al., 2004 [61] | Exotic (native to Mexico/Central America) | Fast-growing timber/shelterbelt; erosion control (but can alter local hydrology) |

| 21 | Cupressus sempervirens L. | Degraded land | Iran | Haghverdi and Kooch, 2020 [48] | Native to eastern Mediterranean | Timber/windbreak; drought-tolerant; ornamental/fast cover |

| 22 | Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (Indian subcontinent) | Nitrogen-fixing; valuable timber; riverbank stabilizer; agroforestry |

| 23 | Derris indica (L.) Pierre | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native (S & SE Asia) | Nitrogen-fixing/climber shrub species; soil cover; multipurpose |

| 24 | Dichrostachys cinerea Wight. and Arn. | Deforestated savanna | Ethiopia | Gebrekirstos et al., 2016 [55] | Native (Africa) | Nitrogen-fixing shrub/tree; soil stabilizer; pioneer in degraded savanna |

| 25 | Elaeagnus angustifolia L. | Degraded salinized lands | Uzbekistan | Djumaeva et al., 2013 [62]; Dubovyk et al., 2016 [63] | Exotic/introduced in Central Asia | Nitrogen-fixing shrub/tree; salt/tolerance; stabilizer in saline soils |

| 26 | Eucalyptus sp. L’Her. | degraded soils in semi-arid area | Marocco | Boulmane et al., 2017 [64] | Exotic (native to Australia) | Fast-growing pioneer; soil cover; timber/fuelwood (but may affect water table and biodiversity) |

| 27 | Ficus glomerata L. | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native (S & SE Asia) | Multipurpose fruit tree; soil stabilization, wildlife food; riparian indicator |

| 28 | Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh. | desurfaced field | Argentina | Ferrari et al., 2010 [65] | Exotic (native to North America) | Fast-growing pioneer; windbreak/rehabilitation; timber potential |

| 29 | Gleditsia triacanthos L. | Degraded salinized lands | Uzbekistan | Djumaeva et al., 2013 [62] | Exotic (native to N America) | Nitrogen-economy facilitator (not a legume fixer but tolerant of poor soils); shade and forage tree |

| 30 | Grewia optiva J.R.Drumm. ex Burret | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (Himalayan foothills/India) | Multipurpose fodder/fuel; soil stabilizer; pioneer in degraded agroforestry |

| 31 | Hippophaë rhamnoides L. | degraded agricultural lands | Romania | Constandache et al., 2016 [66] | Native (Eurasia) | Nitrogen-fixing (via root symbioses), sand/dune stabilizer; salt/drought tolerant |

| 32 | Jatropha curcas L. | Degraded land | Burkina Faso | Kagambega et al., 2011 [67] | Exotic (native to Central America) | Pioneer shrub for degraded land; biodiesel/energy crop; soil cover (but limited nitrogen benefit) |

| 33 | Juniperus phoenicea L. | Arid and semi-arid region | Sardinia | De Dato et al., 2009 [68] | Native (Mediterranean) | Drought-tolerant shrub/tree; soil stabilizer on dry slopes; biodiversity support |

| 34 | Larix principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilg. | forest–grassland–desert transition zone | China | Qian et al., 2024 [69] | Native (China) | Pioneer/tolerant of cold; soil stabilization; reforestation at treeline |

| 35 | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | Degraded land | India | Kalpana Mishra, 2001 [70] | Exotic (native to Mexico/Central America) | Nitrogen-fixing; fast-growing pioneer; agroforestry/fodder (can be invasive) |

| 36 | Liquidambar formosana Hance | Degraded land | China | Li et al., 2024 [71] | Native (China/E Asia) | Mid-successional timber; biodiversity/canopy restoration |

| 37 | Lycium barbarum L. | secondary saline land in an arid irrigated area | China | Ma et al., 2018 [72] | Native (Eurasia/China) | Salt/drought tolerant shrub; fruit (goji); soil stabilization in saline areas |

| 38 | Moringa peregrina (Forssk.) Fiori | degraded desert regions | Iran | Ghoohestani et al., 2025 [73] | Native (Arabian/Horn of Africa/Red Sea region) | Drought-tolerant, multipurpose (food/medicinal/soil stabilizer) |

| 39 | Morus alba L. | sites long-term abandoned from cropping | Turkmenistan | Schachtsiek et al., 2014 [74] | Exotic (native to China) | Fast-growing, fruit/agroforestry; soil cover and livelihoods |

| 40 | Neltuma chilensis (Molina) C.E. Hughes & G.P.Lewis | degraded saline lands | Argentina | Meglioli et al., 2025 [75] | Native (South America/Chile/Argentina) | Nitrogen-fixing (formerly Prosopis chilensis); drought/salinity tolerant; pioneer in arid degraded lands |

| 41 | Neltuma flexuosa (DC.)C.E.Hughes & G.P.Lewis | degraded saline lands | Argentina | Meglioli et al., 2025 [75] | Native (S America) | Nitrogen-fixing; drought tolerant; soil stabilizer in saline/arid zones |

| 42 | Parkia biglobosa Jacq | Degraded semi-arid land | Burkina Faso | Noulekoun et al., 2017 [52] | Native (West Africa) | Nitrogen-fixing (legume); agroforestry; food/soil improvement |

| 43 | Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. | Degraded grassland | Iran | Fataei et al., 2015 [76] | Exotic in Iran (native to Europe) | Fast-growing plantation species for stabilization; timber; mid- to late-successional in cool climates |

| 44 | Pinus elliottii Engelm. | Degraded land | China | Li et al., 2024 [71] | Exotic (native to southeastern USA) | Fast-growing plantation pine; soil stabilization; fuel/timber |

| 45 | Pinus halepensis Mill. | degraded land semi-arid; semi-arid landscape | Jordan; Spain | Omary, 2011 [77]; Chirino et al., 2006 [78] | Native (Mediterranean) | Drought-tolerant pioneer pine; soil stabilization and reforestation in semi-arid Mediterranean |

| 46 | Pinus massoniana Lamb. | Land affected by forest fires | China | Bai et al., 2020 [79] | Native (China) | Pioneer/fire-resilient plantation species; erosion control, fast cover |

| 47 | Pinus nigra J.F.Arnold | Degraded grassland | Iran | Fataei et al., 2015 [76] | Exotic in Iran (native to Mediterranean/Europe) | Timber/stabilizer; mid-successional pine used in reclamation |

| 48 | Pinus oocarpa Schiede ex Schltdl | Degraded land | Nigeria | Jaiyeoba, 2021 [80] | Exotic (native to Central America) | Plantation pine for stabilization and timber; fast-growing pioneer |

| 49 | Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C.Lawson | erodible volcanic soils | Argentina | La Manna et al., 2021 [81] | Exotic (native to western North America) | Pioneer/fast-growing timber pine; soil stabilization |

| 50 | Pinus sylvestris L. | degraded agricultural lands | Romania | Constadache et al., 2021 [82]; Silvestru-Grigore et al., 2018 [83]; Vlad et al., 2019 [84] | Native to Europe (including Romania) | Fast-growing reforestation pine; soil stabilization and timber |

| 51 | Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco | water-limited and degraded land | China | Gao et al., 2018 [85] | Native to East Asia (China) | Drought-tolerant, windbreak/shelterbelt; urban and rural stabilization |

| 52 | Populus euphratica Oliv. | Slat-affected cropland | Uzbekistan | Lamers et al., 2010 [86] | Native (Central Asia/Middle East) | Salt-tolerant riparian/poplar; pioneer for saline sites; groundwater and biodiversity benefits |

| 53 | Populus sibirica (Horth ex Tausch) | Desertification of the semi-arid steppe | Mongolia | Nyam-Osor et al., 2021 [87] | Native (Siberia/Mongolia) | Cold/drought tolerant pioneer; soil stabilization and shelterbelt species |

| 54 | Prosopis chilensis (Mol.) | areas characterized by a high degree of resource degradation | Argentina | Barchuk et al., 1998 [88] | Native (South America) | Nitrogen-fixing legume; drought/salinity tolerant; pioneer in degraded arid lands |

| 55 | Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) Dc. | mine degraded land; degraded sodic soils | India | Ahirwal et al., 2017 [89]; Bhojvaid et al., 1996 [90] | Exotic in India (native to Americas) | Nitrogen-fixing, highly drought/salt tolerant; fast colonizer used for reclamation (but invasive risks) |

| 56 | Prosopis pallida (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Wild.) C.E.Hughes & G.P.Lewis | degraded arid lands | UAE | Aljasmi et al., 2021 [91] | Exotic (native to S America/Pacific coast) | Nitrogen-fixing colonizer; drought tolerant; used for restoration (invasive concerns in some regions) |

| 57 | Prunus armeniaca L. | Degraded land | Uzbekistan | Khamzina et al., 2006 [92] | Native to Central Asia (Armenia/Uzbekistan region) | Fruit tree; agroforestry multipurpose; soil stabilization in degraded orchards |

| 58 | Prunus amygdalus Batsch | Bare-degraded land | Turkey | Erdogan, 2013 [93] | Native to Middle East/Central Asia | Drought-tolerant fruit tree; agroforestry/land use rehabilitation |

| 59 | Prunus cerasoides D. Don | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (Himalayan region/India) | Mid-successional fruit/timber tree; biodiversity support in montane restoration |

| 60 | Pyrus pashia Linnaeus | Degraded land | India | Semwal et al., 2013 [51] | Native (Himalayan foothills/S Asia) | Native fruit tree; soil stabilizer; multipurpose |

| 61 | Quercus robur L. | terrestrial ecosystems degraded by mining | Italy | Manetti et al., 2022 [94] | Native (Europe) | Late-successional keystone tree; long-term canopy and biodiversity restoration; soil stabilization long term |

| 62 | Robinia pseudacacia L. | Degraded lands | Romania | Constandache et al., 2020 [95]; Ciuvǎț et al., 2022 [96]; Enescu, 2019 [97] | Exotic (native to eastern North America) | Nitrogen-fixing pioneer; fast colonizer of degraded sites (can be invasive in some EU contexts) |

| 63 | Salix nigra Marshall | sites long-term abandoned from cropping | Turkmenistan | Schachtsiek et al., 2014 [74] | Exotic (native to North America) | Riparian/wet site pioneer; soil stabilization along waterways; fast cover |

| 64 | Schima superba Gardner & Champ. | Degraded land | China | Li et al., 2024 [71] | Native (SE China) | Timber/mid-successional; shade/canopy restoration in degraded forests |

| 65 | Schima wallichii Choisy | Degraded hilly land | China | Wang et al., 2020 [46] | Native (Himalayan/SE Asia) | Mid-successional timber/canopy species; biodiversity restoration |

| 66 | Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native to India/S Asia | Fruit/multipurpose; tolerant to marginal soils; soil cover and livelihood value |

| 67 | Tamarix androssowii L. | Degraded land | Uzbekistan | Khamzina et al., 2006 [92] | Native/regionally native to Central Asia | Salt/drought tolerant shrub/tree; stabilizes saline soils; riparian/saline land reclamation |

| 68 | Tectona grandis L. | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native to south & SE Asia (India/Myanmar) | Valuable timber species; mid-to-late successional plantation; soil stabilization long term |

| 69 | Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight & Arn. | Degraded formerly barren sodic land | India | Singh et al., 2004 [54] | Native (Indian subcontinent) | Riparian/soil stabilizer; multipurpose tree (timber, medicinal); tolerant of wet/saline soils in riverine settings |

| 70 | Ulmus pumila L. | Desertification of the semi-arid steppe | Mongolia | Nyam-Osor et al., 2021 [87] | Native (Central Asia/Mongolia/Siberia) | Drought/cold tolerant pioneer; wind/shelterbelt; soil stabilization in steppe restoration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Enescu, C.M.; Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L.; Dincă, L.; Timofte, A.I.; Murariu, G. Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Global Review of Practices, Species, and Ecological Outcomes. Forests 2025, 16, 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111743

Enescu CM, Mihalache M, Ilie L, Dincă L, Timofte AI, Murariu G. Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Global Review of Practices, Species, and Ecological Outcomes. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111743

Chicago/Turabian StyleEnescu, Cristian Mihai, Mircea Mihalache, Leonard Ilie, Lucian Dincă, Adrian Ioan Timofte, and Gabriel Murariu. 2025. "Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Global Review of Practices, Species, and Ecological Outcomes" Forests 16, no. 11: 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111743

APA StyleEnescu, C. M., Mihalache, M., Ilie, L., Dincă, L., Timofte, A. I., & Murariu, G. (2025). Afforestation of Degraded Lands: A Global Review of Practices, Species, and Ecological Outcomes. Forests, 16(11), 1743. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111743