Factors Affecting CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in Temperate Forest Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do physicochemical factors related to forest soils (e.g., temperature, moisture, pH, and nutrient availability) influence GHG fluxes?

- How does litter quality, influenced by tree species composition, shape soil C and N dynamics and soil microbial activity, ultimately leading to different GHG flux rates?

- What are the strengths and limitations of the methodologies used to measure GHG fluxes?

2. Soil Properties and GHG Fluxes

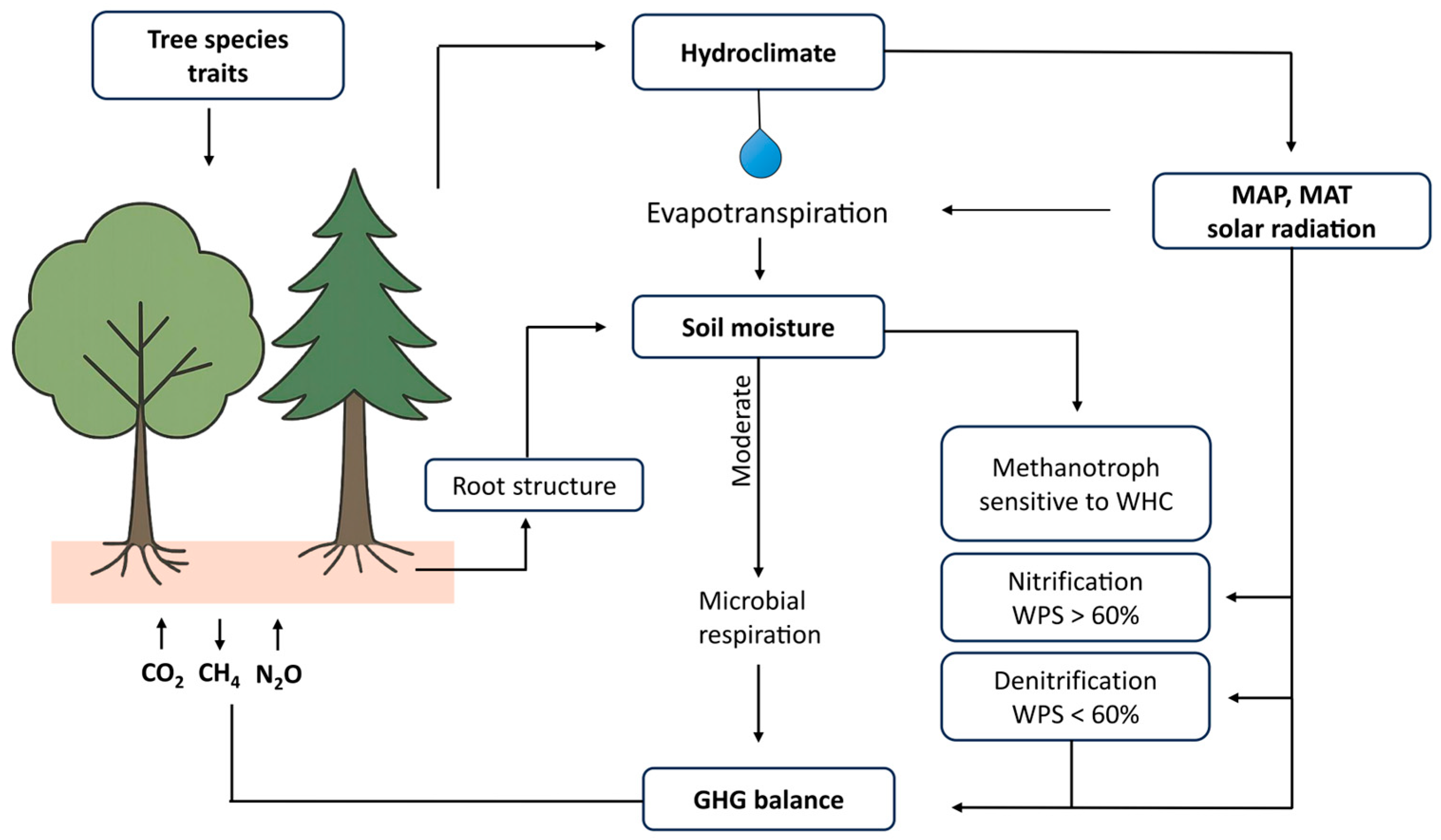

2.1. Soil Moisture Content

| Gases | Country/Forest Ecosystem/Tree Species | Average Temp (°C) | Annual Pr Range (mm) | Study Period | Method Type | Collar Insertion Depth | Influence of Environmental Parameters/Soil Properties on Fluxes | GHG Flux (Annual Avg.) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | South Korea/deciduous/Alnus hirsuta | −9.2–29.2 | 1295 | 20 months | A chamber equipped with an infrared gas analyzer | <1 cm | ST (+), SM (ns) | 150 | [55] |

| South Korea/deciduous/Quercus mongolica | 0.4–26.5 | 1212 | N/A | Automated closed dynamic chamber | 3 cm | ST (+), SM (+) | 549.8–539.5 | [56] | |

| South Korea/coniferous/Pinus koraiensis | −18.5–35.2 | 1358 | 4 years | Closed dynamic chambers | N/A | ST (+), SM (−) | 519.8 | [31] | |

| South Korea/deciduous/Q. serrata, Carpinus laxiflora, C. cordata | −5.2–24.7 | N/A | 6 years | Automatic open–closed chamber | N/A | ST (ns), Pr (+) | 205.3–344.4 | [30] | |

| Same as above | Same as above | 1 year | Same as above | N/A | High Pr (−), Moderate Pr (+) | 224.5–251.3 | [33] | ||

| Poland/coniferous and mixed deciduous/Luzulo pilosae, Cladonio pinetum, Vaccinio pinetum, Potentillo albae, Ficario ulmetum, Carpinion betuli, Dentario glandulosae, L. luzuloides, Fraxino alnetum, | N/A | N/A | N/A | Alkaline absorption method | N/A | pH (+) | 1.10–1.40 * | [57] | |

| United Kingdom/coniferous/P. contorta, P. sylvestris | N/A | N/A | 2 months | Automatic chambers | N/A | ST (+), SM (+) | 39.38 | [32] | |

| CH4 | USA/coniferous and deciduous/Q. rubra, P. strobus, Acer rubrum, Tsuga canadensis | 7.1 | 1066 | 2 years | Closed static chamber | 7 cm | SM (−) | −68.50 | [58] |

| Germany/deciduous/Fagus sylvatica, A. campestre, Fraxinus excelsior | 7.9 | 720 | N/A | Vented static chambers | N/A | ST (+) | −44.85–83.87 | [51] | |

| Poland/coniferous and deciduous/F. excelsior, C. betulus, Picea abies, Populus tremula, Larix decidua, A. glutinosa, P. sylvestris, Q. robur, Prunus avium | 9.9–10.1 | 452–630 | 2 years | Dynamic closed chamber | ≈10 cm | ST (+), SM (−) | −30.06 | [59] | |

| South Korea/deciduous/A. pseudosieboldianum, Q. mongolica | 6.3 | 1578 | 2 years | Static chamber | N/A | ST (−) | −61.30 | [60] | |

| Austria/deciduous/P. alba, F. excelsior | 10.3 | 516 | 1 year | Closed static chamber | N/A | SM (−) | −9.48–58.3 | [61] | |

| France/deciduous/Q. petraea | 11 | 808 | 1 year | Incubation | N/A | SM (−) | −17.71–28.51 | [62] | |

| Czech Republic/deciduous/Q. robur, F. angustifolia, C. betulus, Tilia cordata | 9.3 | 550 | Once a season | Closed static chamber | 5 | ST (−), SM (+) | −34.59–47.92 | [50] | |

| United Kingdom/coniferous/P. contorta, P. sylvestris | N/A | N/A | 2 months | Automatic chambers | N/A | SM (−) | −25.36–70.35 | [32] | |

| N2O | Poland/coniferous and deciduous/P. sylvestris, Q. robur, F. excelsior, C. betulus, L. decidua, A. glutinosa, P. abies, P. tremula, P. avium | 9.9–10.1 | 452–630 | 2 years | Dynamic closed chamber | ≈10 cm | ST (+) | 6.90 | [59] |

| Japan/coniferous and deciduous/Q. variabilis, Chamaecyparis obtusa, P. densiflora, Q. seratta, Cryptomeria japonica, Castanopsis cuspidata | N/A | N/A | Once in a study | Laboratory/Closed container method | N/A | WFPS (+) | 5.24 | [52] | |

| Japan/Tama temperate forest | 14.4 | 1600 | 3 years | Static chamber | ≈5 cm | WFPS (+) | 10.04 | [53] | |

| Germany/deciduous/F. sylvatica, F. excelsior, A. campestre | 7.9 | 720 | N/A | Vented static chambers | N/A | pH (−) | −0.90–5.21 | [51] | |

| China/deciduous/P. davidiana, F. mandshurica, Betula platyphylla, Phellodendron amurense, T. amurensis | −21.5–32 | 600–800 | 2 years | Static chamber | 10 cm | pH (−) | 4.50–39.5 | [63] | |

| Austria/deciduous/P. alba, F. excelsior | 10.3 | 516 | 1 year | Closed static chamber | N/A | SM (+) | 3.08–4.45 | [61] |

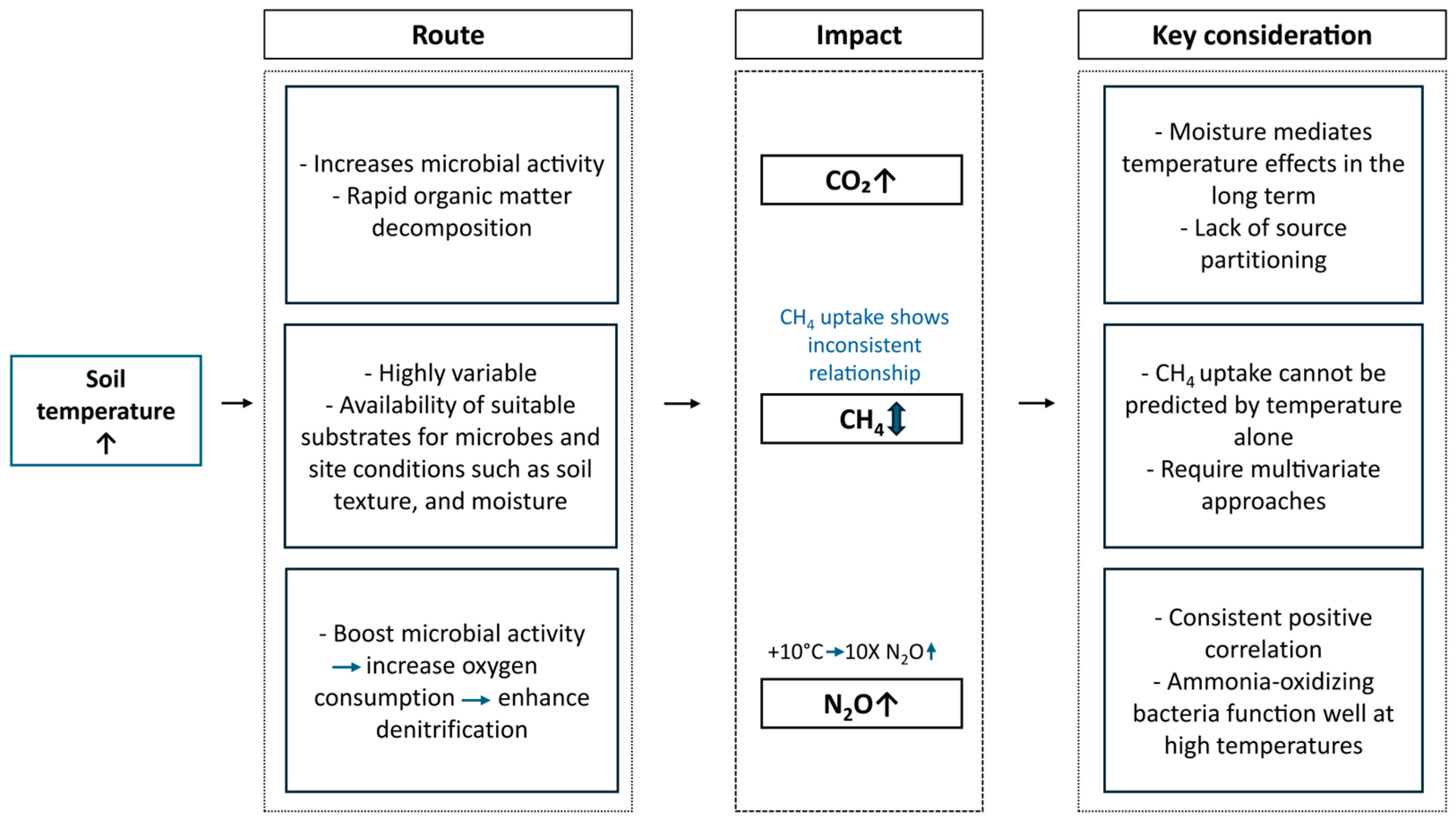

2.2. Soil Temperature

2.3. Soil Chemical Properties

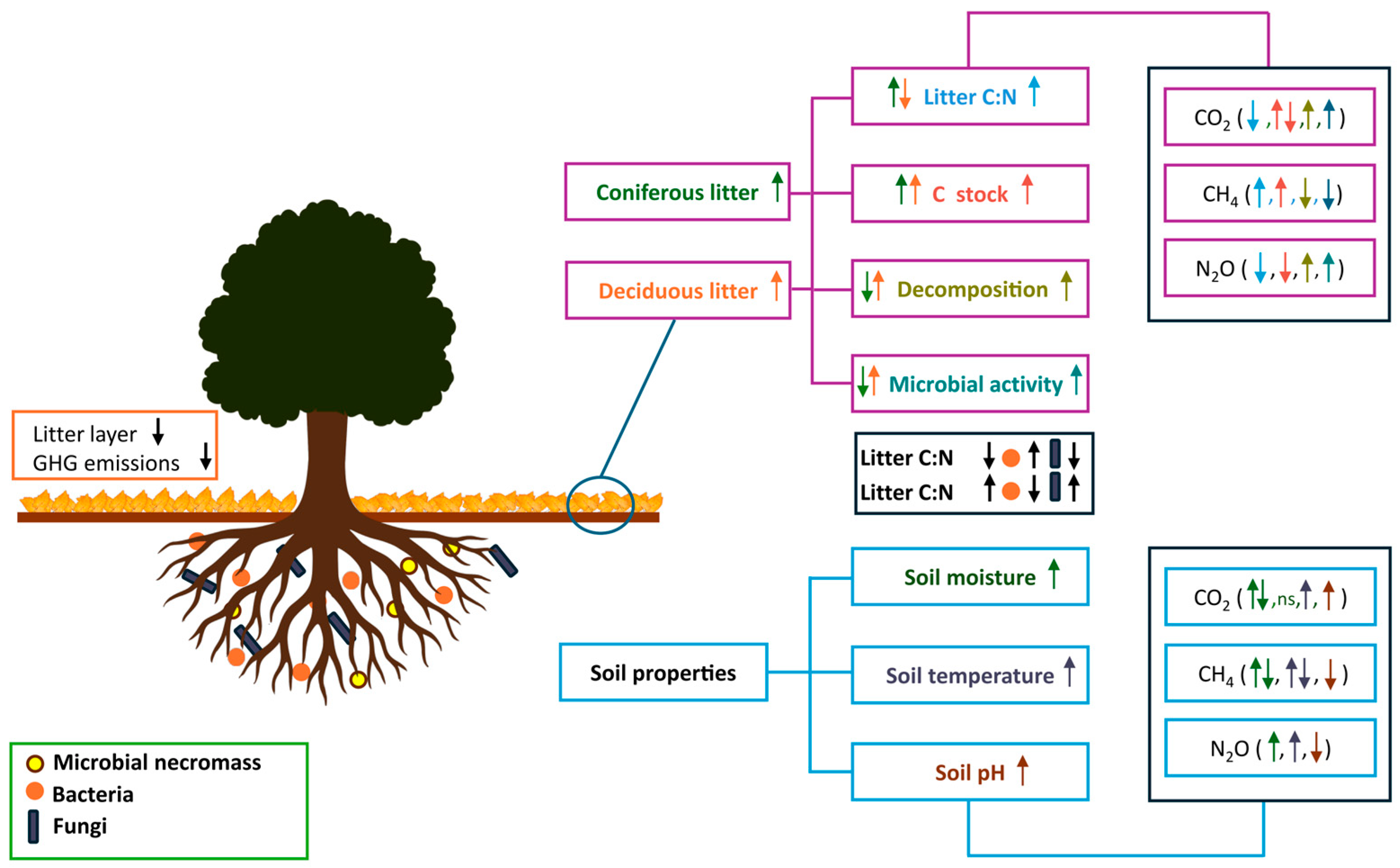

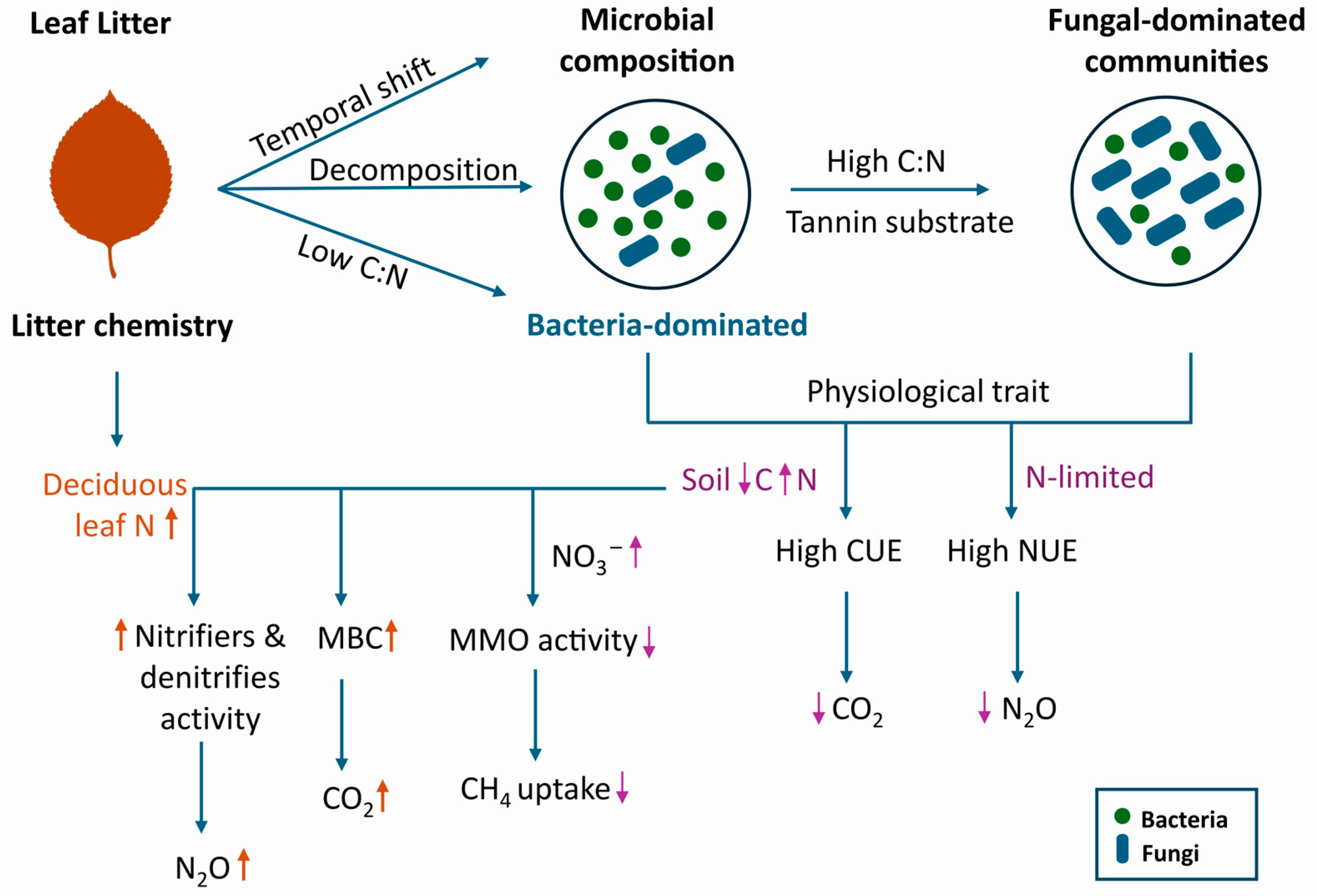

3. Impact of Tree Litter on GHG Fluxes

3.1. Litter Quality, Litter Decomposition, and SOC Stock

3.2. Influence of Litter Quality and Litter Layer on GHG Fluxes

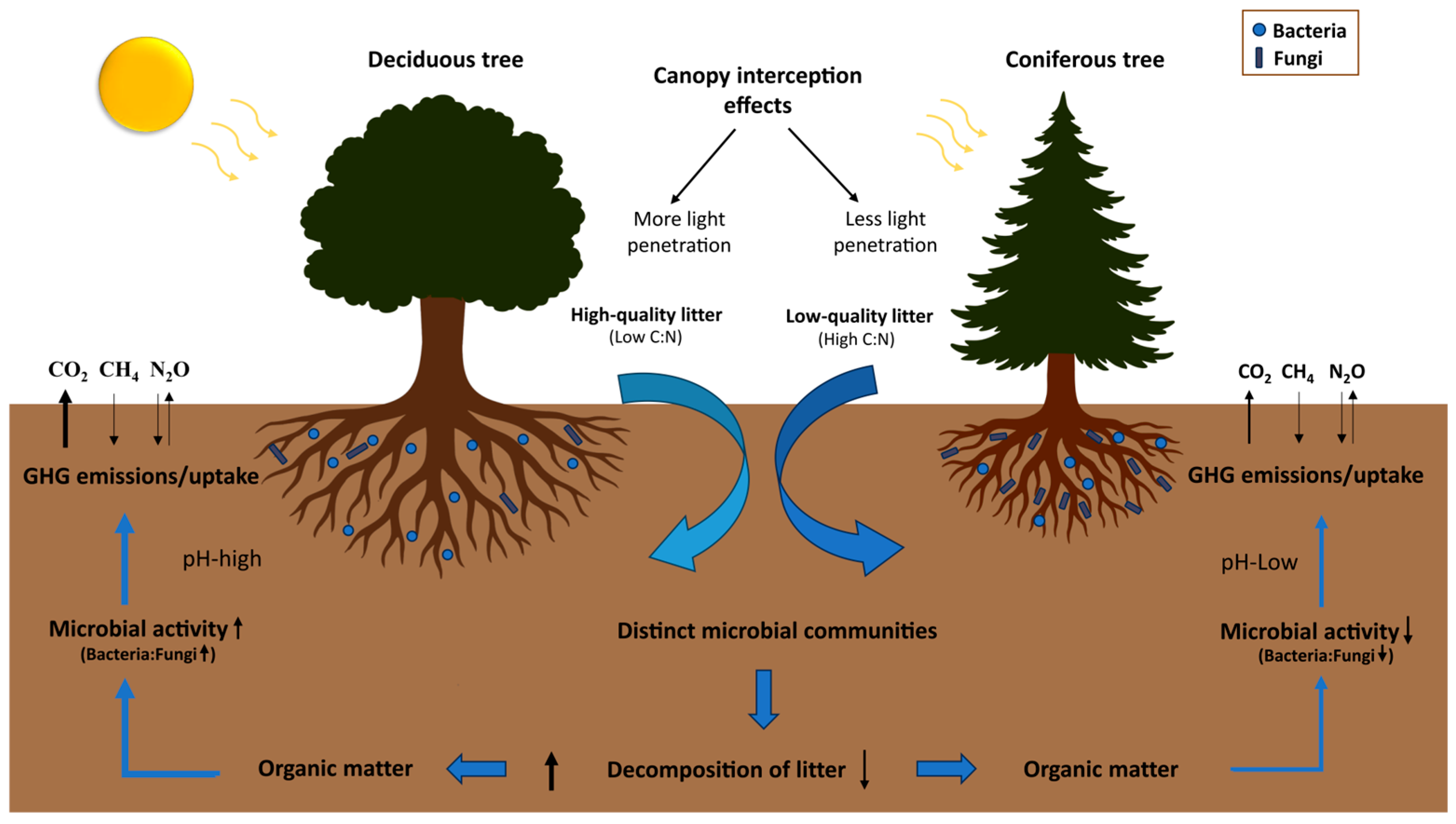

3.3. Tree-Microbe Interactions as Drivers of Soil GHG

4. GHG Measuring Approaches and Their Limitations

5. Future Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oertel, C.; Matschullat, J.; Zurba, K.; Zimmermann, F.; Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review. Geochemistry 2016, 76, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutaur, L.; Verchot, L.V. A global inventory of the soil CH4 sink. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2007, 21, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigley, K.; Armstrong, C.; Smaill, S.J.; Reid, N.M.; Kiely, L.; Wakelin, S.A. Methane cycling in temperate forests. Carbon Balance Manag. 2024, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, W.; Dong, W.; Liu, S. Seasonal patterns of litterfall in forest ecosystem worldwide. Ecol. Complex. 2014, 20, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurner, M.; Beer, C.; Santoro, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Wutzler, T.; Schepaschenko, D.; Shvidenko, A.; Kompter, E.; Ahrens, B.; Levick, S.R.; et al. Carbon stock and density of northern boreal and temperate forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschet, G.T.; Cornwell, W.K.; Wardle, D.A.; Elumeeva, T.G.; Liu, W.; Jackson, B.G.; Onipchenko, V.G.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Tao, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.C. Linking litter decomposition of above- and below-ground organs to plant–soil feedbacks worldwide. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P.; Paul, E.A. Decomposition and soil organic matter dynamics. In Methods in Ecosystem Science; Osvaldo, E.S., Jackson, R.B., Mooney, H.A., Howarth, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Huang, Y.; Hungate, B.A.; Manzoni, S.; Frey, S.D.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Reichstein, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Ciais, P.; Jiang, L.; et al. Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 2023, 618, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, T.; Qadir, M.F.; Khan, K.S.; Eash, N.S.; Yousuf, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Manzoor, R.; Rehman, S.U.; Oetting, J.N. Unraveling the potential of microbes in decomposition of organic matter and release of carbon in the ecosystem. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Matson, P.A.; Vitousek, P. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–529. [Google Scholar]

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Baggs, E.M.; Dannenmann, M.; Kiese, R.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: How well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonard, M.; André, F.; Jonard, F.; Mouton, N.; Procès, P.; Ponette, Q. Soil carbon dioxide efflux in pure and mixed stands of oak and beech. Ann. For. Sci. 2007, 64, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Agnelli, A.E.; Lagomarsino, A. The effect of tree species composition on soil C and N pools and greenhouse gas fluxes in a Mediterranean reforestation. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Frasier, R.; King, L.; Picotte-Anderson, N.; Moore, T.R. Potential fluxes of N2O and CH4 from soils of three forest types in eastern Canada. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, F.A.; Prior, S.A.; Runion, G.B.; Torbert, H.A.; Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Venterea, R.T. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide and increased temperature on methane and nitrous oxide fluxes: Evidence from field experiments. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herb, W.R.; Janke, B.; Mohseni, O.; Stefan, H.G. Ground surface temperature simulation for different land covers. J. Hydrol. 2008, 356, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, L.; Toro-Manríquez, M.; Soler, R.; Huertas-Herrera, A.; Martínez-Pastur, G.; Lencinas, M.V. The Influence of canopy-layer composition on understory plant diversity in southern temperate forests. For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganière, J.; Paré, D.; Bergeron, Y.; Chen, H.Y.H. The Effect of boreal forest composition on soil respiration is mediated through variations in soil temperature and C quality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 53, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, K.; Olsson, B.A.; Olsson, M.; Johansson, U.; Kleja, D.B. Differences in soil properties in adjacent stands of Scots pine, Norway spruce and silver birch in SW Sweden. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, K.A.; Ogle, K.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Cornwell, W.K.; Bönisch, G.; Craine, J.M.; Jackson, B.G.; Kattge, J.; Peltzer, D.A.; Penuelas, J.; et al. Global relationship of wood and leaf litter decomposability: The role of functional traits within and across plant organs. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufler, G.; Kitzler, B.; Schindlbacher, A.; Skiba, U.; Sutton, M.A.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from European soils under different land use: Effects of soil moisture and temperature. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2010, 61, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Osborne, B.; Zou, J. Global patterns of soil greenhouse gas fluxes in response to litter manipulation. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2024, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, C.; He, J.S. Long-term collar deployment leads to bias in soil respiration measurements. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, J.; Loeppmann, S.; Kühnel, A.; Forbush, K.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Cheng, W. Rhizosphere priming of barley with and without root hairs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 100, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B.C. Soil structure and greenhouse gas emissions: A synthesis of 20 years of experimentation. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Niu, S.; Tian, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Yu, Z.; Yan, T.; Yang, W.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J. A global synthesis reveals increases in soil greenhouse gas emissions under forest thinning. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jia, X.; Ma, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Shangguan, Z.; Yan, W. Effects of warming and precipitation changes on soil ghg fluxes: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica, G.; Fernández, M.E.; Juliarena, M.P.; Gyenge, J. Environmental and anthropogenic drivers of soil methane fluxes in forests: Global patterns and among-biomes differences. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6604–6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Peng, C.; Yang, Q.; Meng, F.R.; Song, X.; Chen, S.; Epule, T.E.; Li, P.; Zhu, Q. Model prediction of biome-specific global soil respiration from 1960 to 2012. Earths Future 2017, 5, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Chun, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Long-term characteristics of soil respiration in a Korean cool-temperate deciduous forest in a monsoon climate. Anim. Cells Syst. 2018, 22, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Woo, H.; Choi, B. Soil CO2 concentration and efflux in pine forest plantation region in South Korea. Sens. Mater. 2022, 34, 4639–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subke, J.A.; Moody, C.S.; Hill, T.C.; Voke, N.; Toet, S.; Ineson, P.; Teh, Y.A. Rhizosphere activity and atmospheric methane concentrations drive variations of methane fluxes in a temperate forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 116, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Eom, J.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Chun, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Effect of precipitation on soil respiration in a temperate broad-leaved forest. J. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 42, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.K.; Noh, N.J.; Han, S.; Lee, J.; Son, Y. Soil moisture effects on leaf litter decomposition and soil carbon dioxide efflux in wetland and upland forests. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staněk, L.; Neruda, J.; Ulrich, R. Changes in the concentration of CO2 in forest soils resulting from the traffic of logging machines. J. For. Sci. 2025, 71, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesterdal, L.; Elberling, B.; Christiansen, J.R.; Callesen, I.; Schmidt, I.K. Soil respiration and rates of soil carbon turnover differ among six common European tree species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 264, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhar, N.H.; Park, J.W. Precipitation decreases methane uptake in a temperate deciduous forest. J. Soil Groundw. Environ. 2019, 24, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.S.; Melillo, J.M.; Steudler, P.A.; Chapman, J.W. Soil moisture as a predictor of methane uptake by temperate forest soils. Can. J. For. Res. 2011, 24, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, R.D.; Newkirk, K.M.; Rullo, G.M. Carbon dioxide and methane fluxes by a forest soil under laboratory-controlled moisture and temperature conditions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fest, B.; Hinko-Najera, N.; von Fischer, J.C.; Livesley, S.J.; Arndt, S.K. Soil methane uptake increases under continuous throughfall reduction in a temperate evergreen, broadleaved eucalypt forest. Ecosystems 2017, 20, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; De Roy, K.; Thas, O.; De Neve, J.; Hoefman, S.; Vandamme, P.; Heylen, K.; Boon, N. The more, the merrier: Heterotroph richness stimulates methanotrophic activity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1945–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.J.; Yu, G.R.; Cheng, S.L.; Zhu, T.H.; Wang, Y.S.; Yan, J.H.; Wang, M.; Cao, M.; Zhou, M. Effects of multiple environmental factors on CO2 emission and CH4 uptake from old-growth forest soils. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, T.; Sun, W. Methane uptake in global forest and grassland soils from 1981 to 2010. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Oh, Y.; Lee, S.T.; Seo, Y.O.; Yun, J.; Yang, Y.; Kim, J.; Zhuang, Q.; Kang, H. Soil organic carbon is a key determinant of CH4 sink in global forest soils. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Estiarte, M.; Peñuelas, J. Soil moisture as the key factor of atmospheric CH4 uptake in forest soils under environmental change. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, J.R.; Levy-Booth, D.; Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Microbial and environmental controls of methane fluxes along a soil moisture gradient in a Pacific coastal temperate rainforest. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 1255–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgolewski, A.S.; Caspersen, J.P.; Vantellingen, J.; Thomas, S.C. Tree foliage is a methane sink in upland temperate forests. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skranda, I.; Purvina, D.; Bardule, A.; Petaja, G. Methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from surface of deciduous tree stems and soil in forests with drained and naturally wet organic soils. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Scientific Conference “Engineering for Rural Development”, Jelgava, Latvia, 22–24 May 2024; Volume 23, pp. 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, H.; Katruff, L.; Levin, I. Soil texture parameterization of the methane uptake in aerated soils. Chemosphere 1993, 26, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušek, J.; Acosta, M.; Stellner, S.; Šigut, L.; Pavelka, M. Consumption of atmospheric methane by soil in a lowland broadleaf mixed forest. Plant Soil Environ. 2018, 64, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaiyat, A.; Hossain, M.L.; Kabir, M.H.; Sarker, M.M.H.; Salam, M.M.A.; Li, J. Dynamics of greenhouse gas fluxes and soil physico-chemical properties in agricultural and forest soils. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 3791–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, K.; Takenaka, C.; Ishizuka, S. Relationship between N2O and NO emission potentials and soil properties in Japanese forest soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2009, 55, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yoh, M. Nitrous oxide emissions in proportion to nitrification in moist temperate forests. Biogeochemistry 2020, 148, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zheng, W.; Liao, Q.; Lu, S. Global latitudinal patterns in forest ecosystem nitrous oxide emissions are related to hydroclimate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Yi, M.J.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Son, Y. Estimation of carbon storage, carbon inputs, and soil CO2 efflux of alder plantations on granite soil in central Korea: Comparison with Japanese larch plantation. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.S.; Joo, S.J.; Lee, C.S. Seasonal variation of soil respiration in the Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb.) forests at the cool temperate zone in Korea. Forests 2020, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, B.; Chodak, M.; Niklińska, M. Soil respiration in seven types of temperate forests exhibits similar temperature sensitivity. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevon, F.V.; Gewirtzman, J.; Lang, A.K.; Ayres, M.P.; Matthes, J.H. Tree species effects on soil CO2 and CH4 fluxes in a mixed temperate forest. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 1587–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, A.; Bulak, P.; Khalil, M.I.; Osborne, B. Assessment of soil CO2, CH4, and N2O fluxes and their drivers, and their contribution to the climate change mitigation potential of forest soils in the Lublin region of Poland. Eur. J. For. Res. 2024, 144, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.; Lee, S.; Zoh, K.D.; Kang, H. Methane concentrations and methanotrophic community structure influence the response of soil methane oxidation to nitrogen content in a temperate forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldaschl, E.; Kitzler, B.; Machacova, K.; Schindler, T.; Schindlbacher, A. Stem ch4 and n2o fluxes of Fraxinus excelsior and Populus alba trees along a flooding gradient. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras, N.; Plain, C.; Epron, D. Potential soil methane oxidation in naturally regenerated Oak-dominated temperate deciduous forest stands responds to soil water status regardless of their age—An intact core incubation study. Ann. For. Sci. 2022, 79, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Mu, C. Effects on greenhouse gas (CH4, CO2, N2O) emissions of conversion from over-mature forest to secondary forest and Korean pine plantation in northeast China. Forests 2019, 10, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.J.; Park, S.U.; Park, M.S.; Lee, C.S. Estimation of soil respiration using automated chamber systems in an oak (Quercus mongolica) forest at the Nam-San site in Seoul, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 416, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, S.; Liu, S.; Zhou, H.; Gao, Q.; Cao, G.; Wang, X.; Su, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; et al. Seasonal changes of CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in different types of alpine grassland in the Qinghai Tibetan plateau of China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaraz, J.J.; Zhou, X.; Mabood, F.; Madramootoo, C.; Rochette, P.; Ma, B.L.; Smith, D.L. Greenhouse gas fluxes associated with soybean production under two tillage systems in southwestern Quebec. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Arora, P.; Tomer, R.; Mishra, S.V.; Bhatia, A.; Pathak, H.; Chakraborty, D.; Kumar, V.; Dubey, D.S.; Harit, R.C.; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils under major crops in northwest India. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 542, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.S.C.; Nazaries, L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Macdonald, C.A.; Anderson, I.C.; Hobbie, S.E.; Venterea, R.T.; Reich, P.B.; Singh, B.K. Identifying environmental drivers of greenhouse gas emissions under warming and reduced rainfall in boreal–temperate forests. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 2356–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Ball, T.; Conen, F.; Dobbie, K.E.; Massheder, J.; Rey, A. Exchange of greenhouse gases between soil and atmosphere: Interactions of soil physical factors and biological processes. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.L.; Vargas, R.; Seyfferth, A.; Inamdar, S. Transitional slopes act as hotspots of both soil CO2 emission and CH4 uptake in a temperate forest landscape. Biogeochemistry 2018, 138, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Groffman, P.M. Declines in methane uptake in forest soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8587–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krulwich, T.A.; Hicks, D.B.; Swartz, T.; Ito, M. Bioenergetic adaptations that support alkaliphily. In Physiology and Biochemistry of Extremophiles; Gerday, C., Glansdorff, N., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, B. How methanotrophs respond to pH: A review of ecophysiology. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1034164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, R.A.; Röling, W.F.M.; Laverman, A.M.; Verhoef, H.A. Low nitrification rates in acid Scots pine forest soils are due to pH-related factors. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 53, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Wu, M.; Han, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wan, S. Nitrogen effects on net ecosystem carbon exchange in a temperate steppe. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouridis, F.; Ullah, S. Soil greenhouse gas fluxes, environmental controls, and the partitioning of n 2 o sources in UK natural and seminatural land use types. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2017, 122, 2617–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palacios, P.; Maestre, F.T.; Kattge, J.; Wall, D.H. Climate and litter quality differently modulate the effects of soil fauna on litter decomposition across biomes. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinska, J.; Sewerńiak, P.; Puchałka, R. Litterfall in a Scots pine forest on inland dunes in central Europe: Mass, seasonal dynamics and chemistry. Forests 2020, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.B.; Phillips, R.P. Leaf litter decay rates differ between mycorrhizal groups in temperate, but not tropical, forests. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuille, A.; Schulze, E.D. Carbon dynamics in successional and afforested spruce stands in Thuringia and the Alps. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Soong, J.L.; Horton, A.J.; Campbell, E.E.; Haddix, M.L.; Wall, D.H.; Parton, W.J. Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Prescott, C.E.; Abaker, W.E.A.; Augusto, L.; Cécillon, L.; Ferreira, G.W.D.; James, J.; Jandl, R.; Katzensteiner, K.; Laclau, J.P.; et al. Tamm review: Influence of forest management activities on soil organic carbon stocks: A knowledge synthesis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 466, 118127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Boot, C.M.; Denef, K.; Paul, E. The microbial efficiency-matrix stabilization (mems) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Schmidt, I.K.; Zheng, H.; Heděnec, P.; Bachega, L.R.; Yue, K.; Wu, F.; Vesterdal, L. Tree species effects on topsoil carbon stock and concentration are mediated by tree species type, mycorrhizal association, and n-fixing ability at the global scale. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 478, 118510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, J.M.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Cotrufo, M.F. Incorporation of shoot versus root-derived 13C and 15N into mineral-associated organic matter fractions: Results of a soil slurry incubation with dual-labelled plant material. Biogeochemistry 2018, 137, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton-Smith, S.; Cotrufo, M.F. Pathways of soil organic matter formation from above and belowground inputs in a Sorghum bicolor bioenergy crop. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenerg. 2019, 11, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.E.; Geyer, K.M.; Beidler, K.V.; Brzostek, E.R.; Frey, S.D.; Stuart Grandy, A.; Liang, C.; Phillips, R.P. Fast-decaying plant litter enhances soil carbon in temperate forests but not through microbial physiological traits. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzyakov, Y. Priming Effects: Interactions between living and dead organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Ren, C.; Yu, K.; Zhou, Z.; Phillips, R.P.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dang, Y.; Han, J.; Ye, J.S.; et al. Global pattern of soil priming effect intensity and its environmental drivers. Ecology 2022, 103, e3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Liu, Y.; Freschet, G.T.; Zhang, W.; Yu, X.; Zheng, W.; Guan, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L.; Dijkstra, F.A.; et al. Litter carbon and nutrient chemistry control the magnitude of soil priming effect. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Feng, X. Substrate and community regulations on microbial necromass accumulation from newly added and native soil carbon. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2023, 59, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, C.; Fan, H.L.; Lin, Y.M.; Wu, C.Z. Effects of removing/keeping litter on soil respiration in and outside the gaps in Chinese fir plantation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bréchet, L.M.; Lopez-Sangil, L.; George, C.; Birkett, A.J.; Baxendale, C.; Castro Trujillo, B.; Sayer, E.J. Distinct responses of soil respiration to experimental litter manipulation in temperate woodland and tropical forest. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Hu, G.; Dai, W.; Jiang, P.; Bai, E. The priming effect of soluble carbon inputs in organic and mineral soils from a temperate forest. Oecologia 2015, 178, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.; Ukonmaanaho, L.; Johnson, J.; Benham, S.; Vesterdal, L.; Novotný, R.; Verstraeten, A.; Lundin, L.; Thimonier, A.; Michopoulos, P.; et al. Quantifying carbon and nutrient input from litterfall in European forests using field observations and modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2018, 32, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambus, P.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Sources of nitrous oxide emitted from European forest soils. Biogeosciences 2006, 3, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Greaver, T.L. A review of nitrogen enrichment effects on three biogenic GHGs: The CO2 sink may be largely offset by stimulated N2O and CH4 emissions. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Mo, J.; Zhang, T. Soil-atmosphere exchange of greenhouse gases in subtropical plantations of indigenous tree species. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, S.; Sae-Tun, O.; Kranzinger, L.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Zimmermann, M. Contribution of litter layer to soil greenhouse gas emissions in a temperate beech forest. Plant Soil 2016, 403, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Lam, S.K.; Xu, S.; Lai, D.Y.F. The response of soil-atmosphere greenhouse gas exchange to changing plant litter inputs in terrestrial forest ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madritch, M.D.; Lindroth, R.L. Soil microbial communities adapt to genetic variation in leaf litter inputs. Oikos 2011, 120, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.R.; Kitajima, K.; Mack, M.C. Temporal dynamics of microbial communities on decomposing leaf litter of 10 plant species in relation to decomposition rate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 49, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alonso, M.J.; Díaz-Pinés, E.; Kitzler, B.; Rubio, A. Tree species composition shapes the assembly of microbial decomposer communities during litter decomposition. Plant Soil 2022, 480, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weand, M.P.; Arthur, M.A.; Lovett, G.M.; McCulley, R.L.; Weathers, K.C. Effects of tree species and N additions on forest floor microbial communities and extracellular enzyme activities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2161–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mondéjar, R.; Voříšková, J.; Větrovský, T.; Baldrian, P. The bacterial community inhabiting temperate deciduous forests is vertically stratified and undergoes seasonal dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 87, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, J.J.; Heichen, R.S.; Bottomley, P.J.; Cromack, K.; Myrold, D.D. Community composition and functioning of denitrifying bacteria from adjacent meadow and forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedje, J.M. Ecology of Denitrification and Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium. In Environmental Microbiology of Anaerobes; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.Y.; Tang, Y.F.; Xu, H.F.; Qin, H.L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.Z.; Chen, A.L.; Zhu, B.L. Warming shapes nirs- and nosz-type denitrifier communities and stimulates N2O emission in acidic paddy soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02965-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuffner, M.; Hai, B.; Rattei, T.; Melodelima, C.; Schloter, M.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Jandl, R.; Schindlbacher, A.; Sessitsch, A. Effects of season and experimental warming on the bacterial community in a temperate mountain forest soil assessed by 16S RRNA gene pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vořiškova, J.; Brabcová, V.; Cajthaml, T.; Baldrian, P. Seasonal dynamics of fungal communities in a temperate oak forest soil. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Paredes, C.; Rousk, J. Controls of microbial carbon use efficiency along a latitudinal gradient across Europe. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 193, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.N.; Qi, Y.; Goren, E.; Chiniquy, D.; Sheflin, A.M.; Tringe, S.G.; Prenni, J.E.; Liu, P.; Schachtman, D.P. Root-associated bacterial communities and root metabolite composition are linked to nitrogen use efficiency in sorghum. mSystems 2024, 9, e0119023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, M.; Wanek, W.; Hämmerle, I.; Fuchslueger, L.; Hofhansl, F.; Knoltsch, A.; Schnecker, J.; Takriti, M.; Watzka, M.; Wild, B.; et al. Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon: Nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adingo, S.; Yu, J.R.; Xuelu, L.; Li, X.; Jing, S.; Xiaong, Z. Variation of soil microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE) and its influence mechanism in the context of global environmental change: A review. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Capek, P.; Porada, P.; Thurner, M.; Winterdahl, M.; Beer, C.; Brüchert, V.; Frouz, J.; Herrmann, A.M.; Lindahl, B.D.; et al. Reviews and syntheses: Carbon use efficiency from organisms to ecosystems-definitions, theories, and empirical evidence. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 5929–5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.L.; Eberwein, J.R.; Allsman, L.A.; Grantz, D.A.; Jenerette, G.D. Regulation of CO2 and N2O fluxes by coupled carbon and nitrogen availability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 034008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.A.; Kleber, M.; Torn, M.S. 13C and 15N stabilization dynamics in soil organic matter fractions during needle and fine root decomposition. Org. Geochem. 2008, 39, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, P.J.; Castanha, C.; Torn, M.S.; Bird, J.A. Litter type control on soil C and N stabilization dynamics in a temperate forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Fu, R.; Nottingham, A.T.; Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Yang, X.; Du, H.; Wang, K.; Li, D. Tree species diversity increases soil microbial carbon use efficiency in a subtropical forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 7131–7144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, L.M.; Bhogal, A.; Chadwick, D.R.; McGeough, K.; Misselbrook, T.; Rees, R.M.; Thorman, R.E.; Watson, C.J.; Williams, J.R.; Smith, K.A.; et al. Nitrogen use efficiency and nitrous oxide emissions from five UK fertilised grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, H.; Hagedorn, F. Exploring global data sets to detect changes in soil microbial carbon and nitrogen over three decades. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2024EF004733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgelwa, A.S.; Hu, Y.L.; Xu, W.B.; Ge, Z.Q.; Yu, T.W. Soil carbon and nitrogen availability are key determinants of soil microbial biomass and respiration in forests along urbanized rivers of southern China. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2019, 43, 126351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, J.K.; Ehrmann, O.; Pfeffers, M.; Stemmer, M.; Vollmer, T.; Sommer, M. Soil microbial biomass and activity: The effect of site characteristics in humid temperate forest ecosystems. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2006, 169, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Verma, A.K.; Joshi, R.K.; Hansda, P.; Geise, A.; Garkoti, S.C. Seasonal dynamics of soil and microbial respiration in the banj oak and chir pine forest of the central Himalaya, India. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Xing, X.; Tang, Y.; Hou, H.; Yang, J.; Shen, R.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wei, W. Linking soil N2O emissions with soil microbial community abundance and structure related to nitrogen cycle in two acid forest soils. Plant Soil 2019, 435, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, A.; Bulak, P.; Brzezińska, M.; Khalil, M.I.; Osborne, B. Variations in soil properties and CO2 emissions of a temperate forest gully soil along a topographical gradient. Forests 2021, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Navarro, C.; Díaz-Pinés, E.; Klatt, S.; Brandt, P.; Rufino, M.C.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Verchot, L.V. Spatial variability of soil N2O and CO2 fluxes in different topographic positions in a tropical montane forest in Kenya. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2017, 122, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Doménech-Pascual, A.; Casas-Ruiz, J.P.; Donhauser, J.; Jordaan, K.; Ramond, J.-B.; Priemé, A.; Romaní, A.M.; Frossard, A. Soil organic matter properties drive microbial enzyme activities and greenhouse gas fluxes along an elevational gradient. Geoderma 2024, 449, 116993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; He, D.; Fu, S.; Wan, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; et al. Responses of litter, organic and mineral soil enzyme kinetics to 6 years of canopy and understory nitrogen additions in a temperate forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.M.; Weiss, M.S.; Goodale, C.L.; Adams, M.B.; Fernandez, I.J.; German, D.P.; Allison, S.D. Temperature sensitivity of soil enzyme kinetics under N-fertilization in two temperate forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Schindlbacher, A.; Malo, C.U.; Shi, C.; Heinzle, J.; Kwatcho Kengdo, S.; Inselsbacher, E.; Borken, W.; Wanek, W. Long-term warming of a forest soil reduces microbial biomass and its carbon and nitrogen use efficiencies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Trivedi, C.; Hu, H.; Anderson, I.C.; Jeffries, T.C.; Zhou, J.; Singh, B.K. Microbial regulation of the soil carbon cycle: Evidence from gene–enzyme relationships. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2593–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhi, R.; Zhang, L.; Lei, S.; Farooq, A.; Yan, W.; Song, Z.; Zhang, C. Microbial mechanisms for CO2 and CH4 emissions in Robinia pseudoacacia forests along a north–south transect in the loess plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Hamonts, K.; Lai, K.; Reich, P.B.; Singh, B.K. Losses in microbial functional diversity reduce the rate of key soil processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malghani, S.; Reim, A.; von Fischer, J.; Conrad, R.; Kuebler, K.; Trumbore, S.E. Soil methanotroph abundance and community composition are not influenced by substrate availability in laboratory incubations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 101, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallistova, A.Y.; Merkel, A.Y.; Tarnovetskii, I.Y.; Pimenov, N.V. Methane formation and oxidation by prokaryotes. Microbiology 2017, 86, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.G. Primers: Functional Marker Genes for Methylotrophs and Methanotrophs. In Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Protocols: Primers; McGenity, T.J., Timmis, K.N., Nogales, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Heděnec, P.; Alias, A.; Almahasheer, H.; Liu, C.; Chee, P.S.; Yao, M.; Li, X.; Vesterdal, L.; Frouz, J.; Kou, Y.; et al. Global assessment of soil methanotroph abundances across biomes and climatic zones: The role of climate and soil properties. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 195, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täumer, J.; Kolb, S.; Boeddinghaus, R.S.; Wang, H.; Schöning, I.; Schrumpf, M.; Urich, T.; Marhan, S. Divergent drivers of the microbial methane sink in temperate forest and grassland soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, D.; Kolb, S.; Haumaier, L.; Borken, W. Inhibition of atmospheric methane oxidation by monoterpenes in Norway Spruce and European beech soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 3014–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P.L.E.; Laanbroek, H.J. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraart, A.J.; Steenbergh, A.K.; Ho, A.; Kim, S.Y.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Beyond nitrogen: The importance of phosphorus for CH4 oxidation in soils and sediments. Geoderma 2015, 259, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.S.; Hanson, T.E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulledge, J.; Hrywna, Y.; Cavanaugh, C.; Steudler, P.A. Effects of long-term nitrogen fertilization on the uptake kinetics of atmospheric methane in temperate forest soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 49, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkamp, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Papen, H. Methane oxidation by soils of an N limited and N fertilized spruce forest in the black forest, Germany. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulledge, J.; Schimel, J.P. Low-concentration kinetics of atmospheric CH4 oxidation in soil and mechanism of NH4+ inhibition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Cong, J.; Lu, H.; Sun, X.; Yang, C.; Yuan, T.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Li, D.; et al. Integrated metagenomics and network analysis of soil microbial community of the forest timberline. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P.; Kolaiřík, M.; Štursová, M.; Kopecký, J.; Valášková, V.; Větrovský, T.; Žifčáková, L.; Šnajdr, J.; Rídl, J.; Vlček, Č.; et al. Active and total microbial communities in forest soil are largely different and highly stratified during decomposition. ISME J. 2012, 6, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, T.G.; D’Imperio, L.; Gundersen, P.; Vesterdal, L.; Priemé, A.; Christiansen, J.R. Conversion of cropland to forest increases soil CH4 oxidation and abundance of CH4 oxidizing bacteria with stand age. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 79, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, L.; Xu, X.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F. Linkage between microbial functional genes and net N mineralisation in forest soils along an elevational gradient. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, K.; Denman, S.; Clark, D.R.; Forster, J.; Vanguelova, E.; Brown, N.; Whitby, C. Relationships between nitrogen cycling microbial community abundance and composition reveal the indirect effect of soil pH on Oak decline. ISME J. 2021, 15, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.P.; Zhang, W.J.; Hu, C.S.; Tang, X.G. Soil greenhouse gas fluxes from different tree species on Taihang Mountain, north China. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 1649–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, M.; Priano, M.E.; Fusé, V.S.; Guzmán, S.A.; Juliarena, M.P. Methane oxidation and diffusivity in mollisols under an urban forest in Argentina. Geoderma Reg. 2019, 18, e00230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Xie, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, G.; Lu, X. Non-additive effects of litter diversity on greenhouse gas emissions from alpine steppe soil in northern Tibet. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kang, M.; Ichii, K.; Kim, J.; Lim, J.H.; Chun, J.H.; Park, C.W.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Evaluation of forest carbon uptake in South Korea using the national flux tower network, remote sensing, and data-driven technology. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 311, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.Y.; Lau, S.Y.L.; Midot, F.; Jee, M.S.; Lo, M.L.; Sangok, F.E.; Melling, L. Root exclusion methods for partitioning of soil respiration: Review and methodological considerations. Pedosphere 2023, 33, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, C. Soil-atmospheric exchange of CO2, CH4, and N2O in three subtropical forest ecosystems in southern China. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Mu, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J. Effects on carbon sources and sinks from conversion of over-mature forest to major secondary forests and Korean pine plantation in northeast China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Heng, L.; Müller, C. Measuring Emission of Agricultural Greenhouse Gases and Developing Mitigation Options Using Nuclear and Related Techniques: Applications of Nuclear Techniques for GHGs; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brændholt, A.; Ibrom, A.; Ambus, P.; Larsen, K.S.; Pilegaard, K. Combining a quantum cascade laser spectrometer with an automated closed-chamber system for 13C measurements of forest soil, tree stem and tree root CO2 fluxes. Forests 2019, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, G.T.; Mamtimin, B.; Meixner, F.X. Use of laboratory and remote sensing techniques to estimate vegetation patch scale emissions of nitric oxide from an arid Kalahari savanna. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2008, 5, 4621–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laville, P.; Flura, D.; Gabrielle, B.; Loubet, B.; Fanucci, O.; Rolland, M.N.; Cellier, P. Characterisation of soil emissions of nitric oxide at field and laboratory scale using high resolution method. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 2648–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubinet, M.; Grelle, A.; Ibrom, A.; Rannik, Ü.; Moncrieff, J.; Foken, T.; Kowalski, A.S.; Martin, P.H.; Berbigier, P.; Bernhofer, C.; et al. Estimates of the annual net carbon and water exchange of forests: The EUROFLUX methodology. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1999, 30, 113–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launiainen, S.; Rinne, J.; Pumpanen, J.; Kulmala, L.; Kolari, P.; Keronen, P.; Siivola, E.; Pohja, T.; Hari, P.; Vesala, T. Eddy covariance measurements of CO2 and sensible and latent heat fluxes during a full year in a boreal pine forest trunk-space. Boreal Environ. 2005, 10, 569–588. [Google Scholar]

- Papale, D.; Reichstein, M.; Aubinet, M.; Canfora, E.; Bernhofer, C.; Kutsch, W.; Longdoz, B.; Rambal, S.; Valentini, R.; Vesala, T.; et al. Towards a standardized processing of net ecosystem exchange measured with eddy covariance technique: Algorithms and uncertainty estimation. Biogeosciences 2006, 3, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckman, H.N.; Frank, J.M.; Bradford, J.B.; Miles, B.L.; Massman, W.J.; Parton, W.J.; Ryan, M.G. Forest ecosystem respiration estimated from eddy covariance and chamber measurements under high turbulence and substantial tree mortality from bark beetles. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platter, A.; Scholz, K.; Hammerle, A.; Rotach, M.W.; Wohlfahrt, G. Agreement of multiple night- and daytime filtering approaches of eddy covariance-derived net ecosystem CO2 exchange over a mountain forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 356, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Nakadai, T.; Hirano, T.; Qu, L.; Koike, T.; Fujinuma, Y.; Inoue, G. In situ comparison of four approaches to estimating soil CO2 efflux in a northern larch (Larix kaempferi Sarg.) Forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 123, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Ota, Y.; Eguchi, N.; Kikuchi, N.; Nobuta, K.; Tran, H.; Morino, I.; Yokota, T. Retrieval algorithm for CO2 and CH4 column abundances from short-wavelength infrared spectral observations by the greenhouse gases observing satellite. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2011, 4, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugmacher, D.; Krankina, O.N.; Cohen, W.B.; Friedl, M.A.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Kennedy, R.E.; Nelson, P.; Loboda, T.V.; Kuemmerle, T.; Dyukarev, E.; et al. Comparison and assessment of coarse resolution land cover maps for Northern Eurasia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 3539–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, M.; Mayaux, P.; Woodcock, C.E.; Baccini, A.; Schmullius, C. Some challenges in global land cover mapping: An assessment of agreement and accuracy in existing 1 km datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2538–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.R.; Shao, L.; Leytem, A.B. Completely automated open-path FT-IR spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 393, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, D.W.T.; Deutscher, N.M.; Caldow, C.; Kettlewell, G.; Riggenbach, M.; Hammer, S. A fourier transform infrared trace gas and isotope analyser for atmospheric applications. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 2481–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Saunders, M.; Hastings, A.; Williams, M.; Smith, P.; Osborne, B.; Lanigan, G.; Jones, M.B. Simulating the impacts of land use in Northwest Europe on Net Ecosystem Exchange (NEE): The role of arable ecosystems, grasslands and forest plantations in climate change mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 465, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, P.; Smith, P. Modelling Soil Carbon Dynamics. In Soil Carbon Dynamics: An Integrated Methodology; Kutsch, W.L., Bahn, M., Heinemeyer, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pattey, E.; Edwards, G.C.; Desjardins, R.L.; Pennock, D.J.; Smith, W.; Grant, B.; MacPherson, J.I. Tools for quantifying N2O emissions from agroecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 142, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subke, J.A.; Inglima, I.; Cotrufo, M.F. Trends and methodological impacts in soil CO2 efflux partitioning: A metanalytical review. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 921–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost-Bouré, N.C.; Soudani, K.; Damesin, C.; Berveiller, D.; Lata, J.C.; Dufrêne, E. Increase in aboveground fresh litter quantity over-stimulates soil respiration in a temperate deciduous forest. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 46, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggs, E.M. Partitioning the components of soil respiration: A research challenge. Plant Soil 2006, 284, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.C.; Di, D.R.; Ma, M.G.; Shi, W.Y. Stable isotopes in greenhouse gases from soil: A review of theory and application. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitória, A.P.; Ávila-Lovera, E.; De Oliveira Vieira, T.; Do Couto-Santos, A.P.L.; Pereira, T.J.; Funch, L.S.; Freitas, L.; De Miranda, L.D.A.P.; Rodrigues, P.J.F.P.; Rezende, C.E.; et al. Isotopic composition of leaf carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) of deciduous and evergreen understorey trees in two tropical Brazilian Atlantic forests. J. Trop. Ecol. 2018, 34, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoria, A.P.; Vieira, T.d.O.; Camargo, P.d.B.; Santiago, L.S. Using leaf δ13C and photosynthetic parameters to understand acclimation to irradiance and leaf age effects during tropical forest regeneration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 379, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, W.K.; Wright, I.J.; Turner, J.; Maire, V.; Barbour, M.M.; Cernusak, L.A.; Dawson, T.; Ellsworth, D.; Farquhar, G.D.; Griffiths, H.; et al. Climate and soils together regulate photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination within C3 plants worldwide. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallano, D.M.; Sparks, J.P. Foliar δ15N is affected by foliar nitrogen uptake, soil nitrogen, and mycorrhizae along a nitrogen deposition gradient. Oecologia 2013, 172, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, D.M.; Schiff, S.L.; Spoelstra, J. 15N/14N and 18O/16O stable isotope ratios of nitrous oxide produced during denitrification in temperate forest soils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Mao, J.; Bachmann, C.M.; Hoffman, F.M.; Koren, G.; Chen, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, J.; Tao, J.; Tang, J.; et al. Soil moisture controls over carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions: A Review. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Driver | Microbial Process and Route | GHG Impact and Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Soil pH | Regulates microbial enzyme activity Affects the methane monooxygenase enzyme Affects nitrification by affecting the equilibrium between NH4+ and NO3− | CO2 emissions at neutral pH ↑ CH4 production at pH 4–7 ↑ CH4 consumption at pH 6.6–7.5 ↑ Methanotrophs are adaptable across a wide range of pH levels N2O emissions in acidic soils |

| Nutrient availability | Increases microbial respiration (CO2 ↑) Shifts the methanotrophic activity Stimulates nitrification (N2O ↑) | CO2 increases if C is not limited CH4 uptake is reduced when N/SOC is high N2O is enhanced with increased N inputs |

| Factor | Mechanism | Effect on CO2 | Effect on CH4 Uptake | Effect on N2O | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litter quality | Highly labile C and N in deciduous and mixed forest litter Increases substrate availability | + | + | ↔/+ | [13,96,97,98] |

| Litter removal | Reduces substrate Improves gas exchange Temporary shift in microbial composition | − | + | − | [99,100,101] |

| Doubling the litter amount | Increases labile C May trigger priming | + | + | + | [22,90,93] |

| Species identity | Influences litterfall Shape the soil microbial community | − | + | ↔ | [58,99,100] |

| Organic horizon depth | Deep horizons may restrict gas diffusion | N/A | − | N/A | [75] |

| GHG | Main Microbial Taxa | Key Functional Genes | Environmental Drivers | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, Phanerochaete chrysosporium Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Piloderma, Tylospora fibrillose, Cortinarius biformis | SGA1, TYR, chitinase amyA, pectinesterase, glx, cbhI | Soil pH positively correlates with CO2-cycling gene abundance, while soil moisture, organic C, and N show negative relationships. | [111,133,134,148,149] |

| CH4 | Methylocella, Methylcystis, Methylosinus, Methaothermobacter, Methanoculieus, Methanospirillum, Metanoregula, Upland soil cluster alpha methanotrophs | ppc, glyA, pmoB, mttB, mch, pmoA | Gene abundance is positively influenced by mean annual temperature and precipitation but negatively affected by soil organic C, moisture, NH4+, and pH. | [68,134,136,140,150] |

| N2O | Nitrifiers: Crenarchaeota, Nitrospira, Nitrobacter, Nitrococcus, Nitrosococcus, Denitrifiers: Cyanobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Planctomycetes | amoA, amoB, hao,

nosZ, nirK, nirS gdh | Nitrification gene abundance (amoA, hao) is negatively correlated with NH4+, while denitrification gene abundance (nirS, nirK) shows negative correlations with NO3−. Overall, N2O-related gene abundances are positively influenced by temperature and moisture and negatively affected by NH4+, NO3−, SOC, and C:N ratio. | [68,148,150,151,152] |

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chamber-based (static/dynamic) | Widely used and accessible Suitable for multiple gases Measures GHG at multiple points simultaneously | Long-term collar use alters soil conditions Manual disturbance Limited spatial integration Temperature, pressure, and humidity artifacts No standardization between systems | Regularly monitor collar effects Standardize chamber design and protocols Increase the number of replicates for spatial coverage Use automated chambers |

| Open dynamic chambers | Continuous gas flow prevents accumulation bias Real-time data Less pressure/temperature influence | Technically complex and expensive Limited portability Requires constant power and calibration | Develop cost-effective portable systems Combine with automated data logging Combine with closed chambers for comparison |

| Laboratory | Controls for specific factors (litter, moisture) High repeatability | Transport and storage Poor field representation Homogenization alters soil structure | Avoid excessive sieving Integrate with in situ measurement to enhance reliability |

| Eddy covariance | Continuous high-frequency flux data Captures seasonal/annual trends Large spatial scale ~1 km2 | Underestimates during low turbulence and in dense forest Unable to partition the CO2 sources | Use with chambers for validation Apply machine learning for bias correction Combine stable isotopes to partition the CO2 sources |

| Remote sensing (satellite-based) | Large-scale/global coverage High temporal and spatial resolution Continuous temporal monitoring | Limited accuracy for near-surface emissions Poor performance in cloudy regions Cannot directly quantify soil fluxes Dependence on atmospheric correction models | Integrate satellite data with ground-based chambers Develop algorithms to separate soil vs. vegetation signals |

| Open-path Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) | Near-ground micrometeorological method Multiple-gas detection Continuous monitoring Non-destructive | Short path range (less than 500) Sensitive to weather (temperature, humidity, and turbulence) Scaling results from the site to the regional level is difficult | Combine with flux towers or chamber data for validation Improve correction Develop low-cost, portable FTIR systems for broader field use |

| Modeling (e.g., forest-DNDC) | Simulates multiple processes (decomposition, nitrification, etc.) Covers local to global scales Useful for scenario testing and upscaling | Dependent on input data quality May deviate up to 1 order of magnitude Limited by sparse validation data Regional bias toward temperate zones | Use high-quality, site-specific input data Validate models with chamber and EC data Include long-term monitoring data for model refinement |

| CO2 partitioning root exclusion | Simple and cost-effective | Soil disturbance from trenching Residual roots decomposition biases the data | Combine with isotopic labeling |

| Isotopic labeling (13C, 15N) | Accurately partitions sources (plants, SOM, microbes) Tracks priming and N cycling Enables source tracking (e.g., denitrification via δ15N) | Expensive, complex logistics Difficult to apply in situ Short 13C signal persistence Difficult in low-flux forest soils, low fluxes reduce signal strength | Combine with EC or chamber data Target plots with high activity Comparative studies across forest types |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saher, A.; Kim, G.; Ahn, J.; Chae, N.; Chung, H.; Son, Y. Factors Affecting CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in Temperate Forest Soils. Forests 2025, 16, 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111723

Saher A, Kim G, Ahn J, Chae N, Chung H, Son Y. Factors Affecting CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in Temperate Forest Soils. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111723

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaher, Amna, Gaeun Kim, Jieun Ahn, Namyi Chae, Haegeun Chung, and Yowhan Son. 2025. "Factors Affecting CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in Temperate Forest Soils" Forests 16, no. 11: 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111723

APA StyleSaher, A., Kim, G., Ahn, J., Chae, N., Chung, H., & Son, Y. (2025). Factors Affecting CO2, CH4, and N2O Fluxes in Temperate Forest Soils. Forests, 16(11), 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111723