Balancing Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Through Forest Management Choices—A Case Study from Hungary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Description of the Forestry Region

2.2. Description of the Forest Subcompartment

2.3. SiteViewer 3.0 Climate Change Projections and Associated Target Stand Recommendations

2.4. Field Measurement

2.5. Forest Management Scenarios

2.6. Principles and Regulatory Constraints Guiding Scenario Design

- Additionality: Projects must demonstrate that carbon sequestration or emission reductions go beyond business-as-usual practices, legal obligations, and common industry standards.

- Permanence: Carbon removals should be long-lasting and resilient to reversal from natural disturbances or human interventions.

- Leakage Prevention: The project should not indirectly cause increased emissions elsewhere (e.g., displacement of timber harvesting).

- Do No Harm and Co-Benefits: Activities must not cause significant harm to ecosystems or biodiversity.

- Quantification: Carbon removals must be measurable, reportable, and verifiable using robust, transparent, and scientifically sound methodologies.

2.7. Overview of the Yield Tables Applied

- Scots pine: Solymos Rezső yield table, 1966;

- Hornbeam: Kollár Tamás yield table, 2024;

- Black locust: Fekete Zoltán and Sopp László yield table, 1974;

- Native poplar: Palotás Ferenc, Szodfridt István, and Sopp László yield table, 1974;

- Turkey oak: Kollár Tamás yield table, 2023.

2.8. Procedure for Carbon Balance Calculation

2.9. Method for Calculating the Amount of Carbon Credit Generated

2.10. Financial Calculations

| Input Data for Economic Calculations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Value (EUR/m3) | Data source | |

| Prices of Scots Pine assortment | ||

| Log | 60 | OSAP (2024) [48] |

| Low-grade roundwood | 32 | OSAP (2024) [48] |

| Logging cost | ||

| Contractor fee per cubic metre | 21 | Ministry of Agriculture, 2025 [50] |

| Financial baseline data | ||

| Discount rate (low risk) | 2% | own estimate |

| Forest regeneration costs | ||

| Harvesting Scots pine and regenerating with Scots pine | 1896 | Nagy [49] |

| Harvesting Scots pine and regenerating with Black locust | 1233 | Nagy [49] |

| Harvesting Scots pine and regenerating with Native poplar | 1123 | Nagy [49] |

| Harvesting Scots pine and regenerating with Turkey oak | 1750 | Nagy [49] |

- TDCM: Total Discounted Contribution Margin;

- LCMt: Logging Contribution Margin;

- CCIt: Carbon Credit Income;

- r: discount rate;

- t: year variable and index;

- n: length of the study period.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate Adaptation Evaluation

4.2. Climate Change Mitigation Potential of IFM Projects and Economic Trade-Offs

4.3. Uncertainty and Permanence Challenges in Carbon Farming Projects

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verkerk, P.J.; Delacote, P.; Hurmekoski, E.; Kunttu, J.; Matthews, R.; Mäkipää, R.; Mosley, F.; Perugini, L.; Reyer, C.P.; Roe, S.; et al. Forest-Based Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Europe; From Science to Policy 14; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2022; ISBN 978-952-7426-22-7. [Google Scholar]

- Korosuo, A.; Pilli, R.; Abad Viñas, R.; Blujdea, V.N.; Colditz, R.R.; Fiorese, G.; Grassi, G. The role of forests in the EU climate policy: Are we on the right track? Carbon Balance Manag. 2023, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csépányi, P.; Csór, A. Economic Assessment of European Beech and Turkey Oak Stands with Close-to-Nature Forest Management. Acta Silv. Lignaria Hung. 2017, 13, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lundmark, T.; Bergh, J.; Nordin, A.; Fahlvik, N.; Poudel, B.C. Comparison of carbon balances between continuous-cover and clear-cut forestry in Sweden. Ambio 2016, 45 (Suppl. S2), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuluvainen, T.; Tahvonen, O.; Aakala, T. Even-aged and uneven-aged forest management in boreal Fennoscandia: A review. Ambio 2012, 41, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukkala, T.; Lahde, E.; Laiho, O.; Pukkala, T. Continuous cover forestry in Finland—Recent research results. In Continuous Cover Forestry; Gadow, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 85–128. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J.B.; Angelstam, P.; Bauhus, J.; Carvalho, J.F.; Diaci, J.; Dobrowolska, D.; Gazda, A.; Gustafsson, L.; Krumm, F.; Knoke, T.; et al. Closer-to-Nature Forest Management; From Science to Policy 12; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2022; ISBN 978-952-7426-19-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuurs, G.-J.; Delacote, P.; Ellison, D.; Hanewinkel, M.; Lindner, M.; Nesbit, M. A New Role for Forests and the Forest Sector in the EU Post-2020 Climate Targets; From Science to Policy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet-Navarro, P.; Jochheim, H.; Kroiher, F.; Muys, B. Effect of cascade use on the carbon balance of the German and European wood sectors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüter, S. Projections of Net Emissions from Harvested Wood Products in European Countries; Work Report No. 2011/x of the Institute of Wood Technology and Wood Biology; Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute (vTI): Hamburg, Gemany, 2011; 62p.

- Leskinen, P.; Cardellini, G.; González-García, S.; Hurmekoski, E.; Sathre, R.; Seppälä, J.; Smyth, C.; Stern, T.; Verkerk, P.J. Substitution effects of wood-based products in climate change mitigation. In From Science to Policy 7; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siiskonen, H. From economic to environmental sustainability: The forest management debate in 20th century Finland and Sweden. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, H.; Bey, N.; Duin, L.; Frelih-Larsen, A.; Maya-Drysdale, L.; Stewart, R.; Pätz, C.; Hornsleth, M.N.; Heller, C.; Zakkour, P. Certification of Carbon Removals Part 2: A Review of Carbon Removal Certification Mechanisms and Methodologies. Umweltbundesamt GmbH. 2021. Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2022/50035-Certification-of-carbon-removal-part-2-web.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Cho, S.; Baral, S.; Burlakoti, D. Afforestation/Reforestation and avoided conversion carbon projects in the United States. Forests 2025, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shell; Boston Consulting Group. The Voluntary Carbon Market: 2022 Insights and Trends; Shell Energy: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.shell.com/shellenergy/othersolutions/carbonmarketreports.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Institute of International Finance. TSVCM Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets. Final Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.iif.com/Portals/1/Files/TSVCM_Report.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-4648-2006-9. [Google Scholar]

- Haya, B.K.; Abayo, A.; So, I.; Elias, M.V. Voluntary Registry Offsets Database V10; Berkeley Carbon Trading Project; Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://gspp.berkeley.edu/faculty-and-impact/centers/cepp/projects/berkeley-carbon-trading-project/offsets-database (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EU/2024/3012: Regulation (EU) 2024/3012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 Establishing a Union Certification Framework for Permanent Carbon Removals, Carbon Farming and Carbon Storage in Products. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L_202403012 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Borovics, A.; Ábri, T.; Benke, A.; Illés, G.; Király, É.; Kovács, Z.; Schiberna, E.; Keserű, Z. Carbon credit revenue assessment for four shelterbelt projects following EU CRCF protocols. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führer, E. Magyarország Erdészeti Tájai. V; Nyugat-Dunántúl Erdészeti Tájcsoport; Agrárminisztérium Nemzeti Földügyi Központ: Budapest, Hungary, 2022; 652p.

- SiteViewer 3.0. 2025. Available online: http://www.ertigis.hu/siteviewer.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Illés, G.; Fonyó, T.; Borovics, A. SiteViewer: A decision support tool for forest management. Hung. Agric. Res. Environ. Manag. Land Use Biodivers. 2024, 34, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- NIR. National Inventory Report for 1985–2020. Hungary; Hungarian Meteorological Service: Budapest, Hungary, 2022.

- Kollár, T. Fatermési táblák és függvények paraméter készlete a magyarországi fafajok erdőállományinak becsléséhez. In Proceedings of the Erdészeti Tudományos Konferencia, Sopron, Hungary, 5–6 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kollár, T. Új adatok a magyarországi gyertyánosok (Carpinus betulus) faterméséről. In Proceedings of the Erdészeti Tudományos Konferencia, Sopron, Hungary, 10 February 2022; Soproni Egyetem Kiadó: Sopron, Hungary, 2022; pp. 8, 109–116, 316. [Google Scholar]

- Kollár, T. Csertölgy (Quercus cerris) állományok fatermési függvénye és táblája az erti tartamkísérleti hálózatának adatbázisa alapján. Erdtud. Közlemények 2023, 13, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollár, T.; Rédei, K. Parametrikus Fatermési Táblák; Soproni Egyetem Kiadó: Sopron, Hungary, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi, Z. A hazai erdők üvegház hatású gáz leltára az IPCC módszertana szerint. Erd. Kut. 2008, 92, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Good Practice Guidance for Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry; Penman, J., Gytarsky, M., Hiraishi, T., Krug, T., Kruger, D., Pipatti, R., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., et al., Eds.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) for the IPCC: Yamato-shi, Japan, 2003; ISBN 4-88788-003-0. [Google Scholar]

- Borovics, A.; Király, É.; Kottek, P. Projection of the Carbon Balance of the Hungarian Forestry and Wood Industry Sector Using the Forest Industry Carbon Model. Forests 2024, 15, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovics, A. ErdőLab: A Soproni Egyetem erdészeti és faipari projektje: Fókuszban az éghajlatváltozás mérséklése. Erd. Lapok 2022, 157, 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Härtl, F.H.; Höllerl, S.; Knoke, T. A new way of carbon accounting emphasises the crucial role of sustainable timber use for successful carbon mitigation strategies. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2017, 22, 1163–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Calvo Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize, S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P., Federici, S., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Király, É.; Börcsök, Z.; Kocsis, Z.; Németh, G.; Polgár, A.; Borovics, A. A new model for predicting carbon storage dynamics and emissions related to the waste management of wood products: Introduction of the HWP-RIAL model. Acta Agrar. Debreceniensis 2023, 1, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, É.; Börcsök, Z.; Kocsis, Z.; Németh, G.; Polgár, A.; Borovics, A. Climate change mitigation through carbon storage and product substitution in the Hungarian wood industry. Wood Res. 2024, 69, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, M.; Joosten, R.; Frühwald, A. Assessing fossil fuel substitution through wood use based on long-term simulations. Carbon Manag. 2016, 7, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, M.; Köhl, M.; Mues, V.; Olschofsky, K.; Frühwald, A. Modeling the CO2-effects of forest management and wood usage on a regional basis. Carbon Balance Manag. 2015, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottek, P. Hosszútávú Erdőállomány Prognózisok. Ph.D. Thesis, Roth Gyula Erdészeti és Vadgazdálkodási Tudományok Doktori Iskola, Soproni Egyetem, Sopron, Hungary, 2023; 142p. [Google Scholar]

- Kottek, P.; Király, É.; Mertl, T.; Borovics, A. The re-parametrization of the DAS model based on 2016–2021 data of the National Forestry Database: New results on cutting age distributions. Acta Silv. Lignaria Hung. Int. J. For. Wood Environ. Sci. 2023, 19, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllyviita, T.; Soimakallio, S.; Judl, J.; Seppälä, J. Wood substitution potential in greenhouse gas emission reduction–review on current state and application of displacement factors. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Environmental Information System. 2024. Available online: http://web.okir.hu/en/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Schweinle, J.; Köthke, M.; Englert, H.; Dieter, M. Simulation of forest-based carbon balances for Germany: A contribution to the ‘carbon debt’ debate. Wires Energy Environ. 2018, 7, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, P.; Weisser, W.W.; Ambarlı, D.; Bässler, C.; Buscot, F.; Hofrichter, M.; Hoppe, B.; Kellner, H.; Minnich, C.; Moll, J.; et al. Regional variation in deadwood decay of 13 tree species: Effects of climate, soil and forest structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 541, 121094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSAP. Erdészeti Ársatisztikák. 2024. Available online: https://agrarstatisztika.kormany.hu/erdogazdalkodas2 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Nagy, I. (Ed.) Megújított Erdei Vadkárfelvételi és Értékelési Útmutató, Készült a Magánerdő Tulajdonosok és Gazdálkodók Országos Szövetségének a Megbízásából; Erdészeti Tudományos Intézet (ERTI): Sopron, Hungary, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture Statistics Provided by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry. 2025. Available online: https://agrarstatisztika.kormany.hu/adatok-idosorok (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Griscom, B.W.; Cortez, R. The case for improved forest management (IFM) as a priority REDD+ strategy in the tropics. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2013, 6, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargione, J.E.; Bassett, S.; Boucher, T.; Bridgham, S.D.; Conant, R.T.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Falcucci, A.; Fourqurean, J.W.; Gopalakrishna, T.; et al. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarakka, L.; Cornett, M.; Domke, G.; Ontl, T.; Dee, L.E. Improved forest management as a natural climate solution: A review. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2021, 2, e12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarakka, L.; Rothey, J.; Dee, L.E. Managing forests for carbon: Status of the forest carbon offset markets in the United States. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, J.; Nolte, C.; Potts, M.; Baumann, M.; Haya, B.K.; Butsic, V. Little evidence of management change in California’s forest offset program. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuoli, I.; Martelli, A.; Falconi, I.; Galioto, F.; Lasorella, M.V.; Maurino, S.; Dara Guccione, G. Lessons learned from existing carbon removal methodologies for agricultural soils to drive european union policies. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsøe, M.H.; Facq, E.; Criscuoli, I.; Martínez-García, L.B.; Heidecke, C.; Gallardo, L.A.; Martelli, A.; Hagemann, N.; Smit, B.; van der Kolk, J.; et al. Carbon farming: The foundation for carbon farming schemes—Lessons learned from 160 European schemes. Land Use Policy 2025, 158, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario Name | Core Management Action | Rationale for Species Selection | Role in the Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Baseline | Harvest the overmature stand and regenerate with the same species | Since the current tree stand is overmature, the obvious option is to harvest it and regenerate it with the same species. The long-term rationale of this approach is to further cultivate Scots pine in the study area as it can produce high-value timber on this site. For the carbon sequestration calculations, this scenario was selected as the baseline (Business as Usual, BAU), as it represents the most probable management pathway, against which the mitigation impacts of the other alternatives can be compared. | Baseline (BAU)—most probable management pathway |

| Scenario 2: Extended forest rotation | Keep current stand, extend rotation by 25 years | In this scenario the current tree stand is kept, and the rotation period is extended for a further 25 years. This is a feasible option only if climatic conditions do not change significantly and the vitality of the stand does not undergo further decline. However, considerable dieback is already present, which means that growing stock is expected to gradually decrease. Under conditions of climate aridification, a sudden stand collapse is also possible | Alternative—mitigation comparison with BAU |

| Scenario 3: Extended rotation with total stand mortality | Keep current stand, extend rotation by 25 years, but 100% mortality occurs within 10 years | In this scenario, the stand is maintained without harvesting for 25 years, but 100% mortality occurs within 10 years. According to the forest manager’s expert judgement, this is the most likely outcome under extended forest rotation. | Alternative—hazard scenario, shows worst-case risk |

| Scenario 4: Conversion to black locust | Clear-cut and regenerate with black locust | Black locust is an introduced species, which is not only tolerant to a wide range of site conditions, but it has only a few pests too. This option would reduce the naturalness status of the forest and is therefore included only as a thought experiment. The inclusion of black locust is justified by its good regeneration potential under aridifying climate conditions, its faster growth rate, and shorter rotation period, which offer more favourable financial indicators and faster carbon sequestration. | Alternative—mitigation comparison with BAU |

| Scenario 5: Conversion to grey poplar | Clear-cut and regenerate with grey poplar | Grey poplar is one of the native species that are well-suited to arid environment. Although it is more widespread on sandy soils, it remains a viable option on the study site, where its simple sylviculture requirements make it a worthwhile candidate. Compared with black locust, this option does not reduce the naturalness status, while still being a fast-growing, short-rotation species that enables efficient carbon sequestration. Its main disadvantage is the lower value of the timber produced. | Alternative—mitigation comparison with BAU |

| Scenario 6: Conversion to Turkey oak | Clear-cut and regenerate with Turkey oak | This scenario represents a restoration of an oak dominated tree stand, which would naturally occur in the study site. However, due to the change in climate conditions Sessile oak is replaced by Turkey oak, as it is more tolerant to dry conditions. This scenario is viable only if climate change impacts are not overly severe. The result would be a long-rotation stand with favourable naturalness characteristics. | Alternative—mitigation comparison with BAU |

| Conversion Factors and Root-to-Shoot Ratio Used for Converting the Living Timber Stock to Carbon Content According to the GHG Inventory | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | C fraction | Root-to-shoot ratio | |

| Unit of measurement | Tonnes of dry matter/m3 of living timber stock | Tonnes of C/tonne of dry matter | Tonnes of dry matter/tonne of dry matter |

| Data source | Somogyi (2008) [31] and NIR 2022 ([26], p. 383) | 2006 IPCC GL V4, Ch4, Table 4.3 in ref. [32] | IPCC GPG for LULUCF 2003 Annex 3A.1 Table 3A.1.8 in ref. [33] |

| Target stand type | |||

| Turkey oak | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| Hornbeam | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| Black locust | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| Native poplar | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| Scots pine | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.25 |

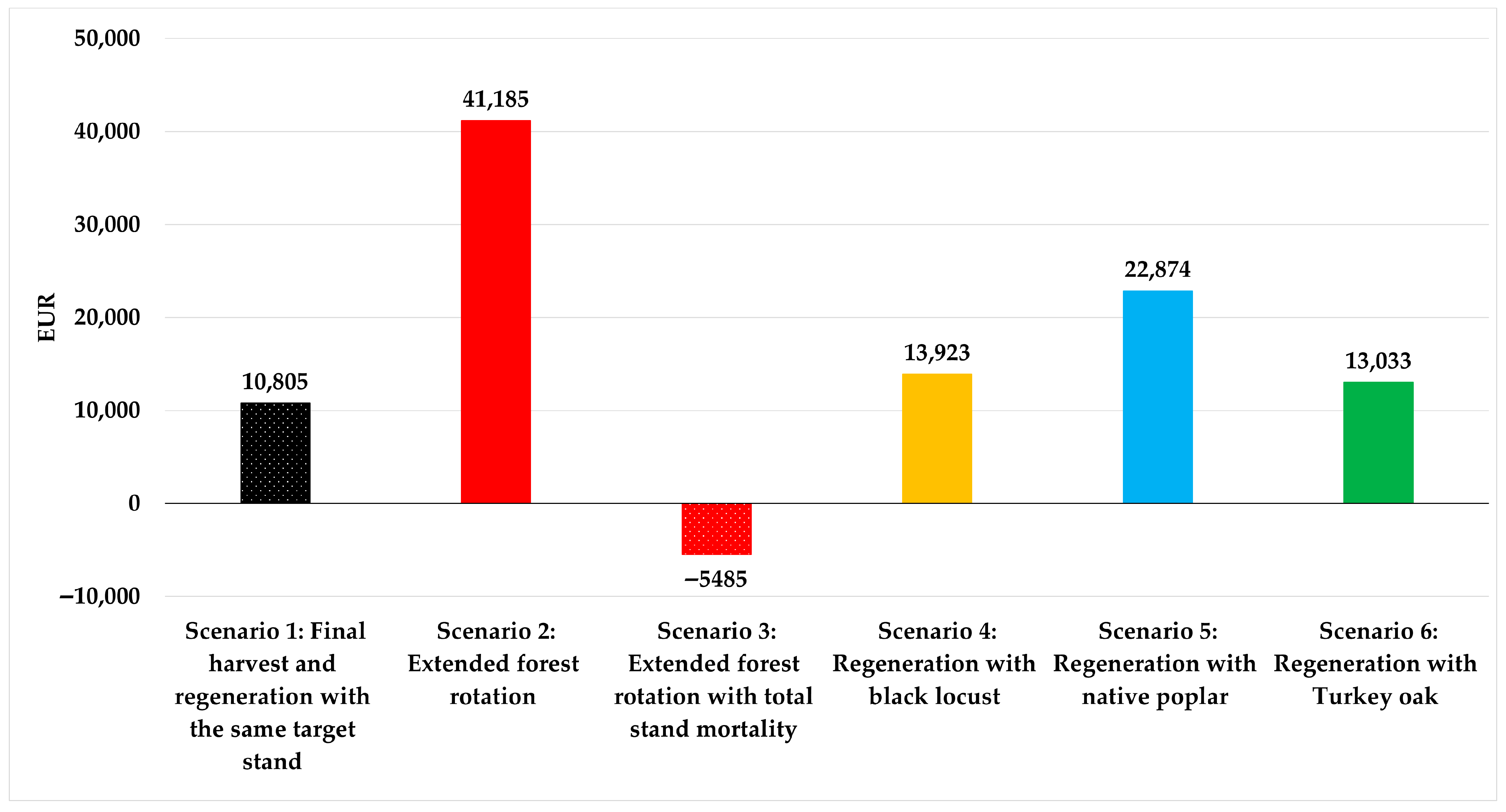

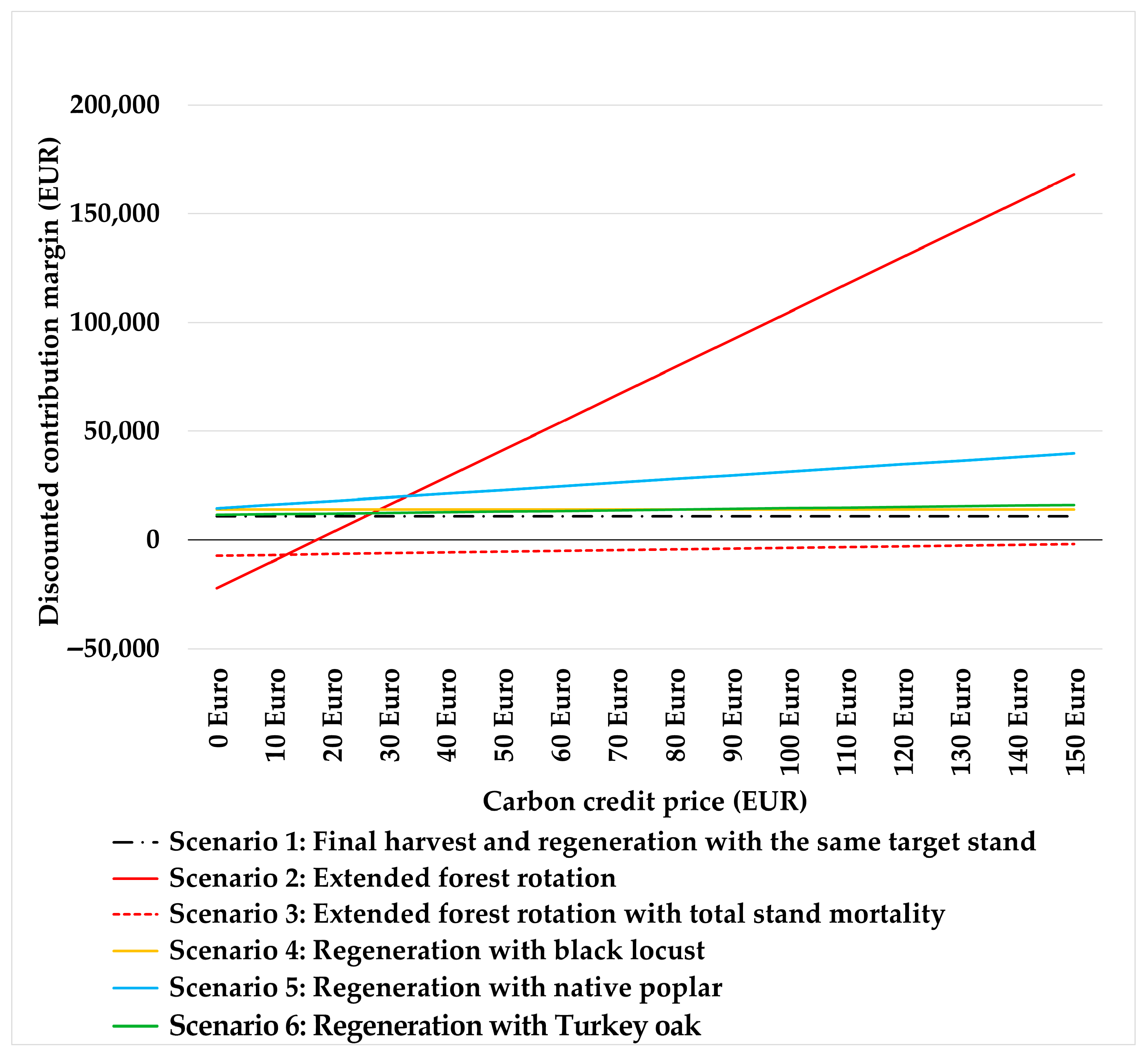

| Scenario Description | Scenario 1: Scots Pine Regeneration (Baseline) | Scenario 2: Extended Forest Rotation | Scenario 3: Extended Forest Rotation with Total Stand Mortality | Scenario 4: Black Locust Regeneration | Scenario 5: Native Poplar Regeneration | Scenario 6: Turkey Oak Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | The 99-year-old Scots pine stand is regenerated with the same tree species. | Improved forest management with additional carbon sequestration, maintaining the stand for an additional 25 years without harvesting. Scenario with minor CO2 emissions. | The stand is maintained without harvesting for another 25 years, but with 100% mortality within 10 years. According to the forest manager, this is the most likely scenario. | After clear-cutting of Scots pine, artificial regeneration is carried out with black locust. Due to the biodiversity criterion of the CRCF regulation, black locust generates no carbon revenue. | After clear-cutting of Scots pine, artificial regeneration is carried out with a native poplar species. This is also a possible scenario with additional carbon sequestration. | After clear-cutting of Scots pine, artificial regeneration is carried out with Turkey oak. This is also a possible scenario with additional carbon sequestration. |

| Growing stock 2030 (m3/ha) | 4.7 | 411.7 | 170.0 | 23.8 | 8.9 | 8.3 |

| Growing stock 2040 (m3/ha) | 45.7 | 384.0 | 0.0 | 123.2 | 90.4 | 38.9 |

| Growing stock 2050 (m3/ha) | 101.7 | 351.3 | 0.0 | 218.3 | 196.4 | 74.7 |

| Harvested timber 2025 (gross m3/ha) | 425.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 425.3 | 425.3 | 425.3 |

| Harvested timber 2050 (gross m3/ha) | 0.0 | 351.3 | 148.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mitigation effect compared to baseline (tCO2/ha) | baseline | 203.8 | 23.0 | 146.8 | 44.5 | 4.3 |

| Discounted logging income (EUR/ha) | 13,465 | 981 | 0 | 13,465 | 13,465 | 13,465 |

| Discounted logging cost (EUR/ha) | 9269 | 4575 | 1928 | 9269 | 9269 | 9269 |

| Discounted regeneration cost (EUR/ha) | 1897 | 1133 | 1133 | 1233 | 1123 | 1750 |

| Discounted carbon credit income at 50 €/tCO2 (EUR/ha) | 0.0 | 13,490.6 | 1894.0 | 0.0 | 1794.5 | 327.2 |

| Total Discounted Contribution Margin at 50 €/tCO2 (EUR/ha) | 2298.9 | 8762.8 | −1167.0 | 2962.3 | 4866.8 | 2772.8 |

| Advantages | Sufficient experience is available at the given forestry directorate. Well-known market perception. | Additional revenue without costs or risks, in a newly emerging carbon market. | In the case of the stand collapse scenario, the extended forest cycle has no advantages. | Management has low risk, capable of significant timber production in a short time. | Native species, therefore, increases biodiversity compared to Scots pine; offers a good solution for the climate change scenario we modelled. Revenue from both the carbon market and timber production. | Native species, therefore, increases biodiversity compared to Scots pine; offers a good solution for the climate change scenario we modelled. Revenue from both the carbon market and timber production. |

| Disadvantages | Management with Scots pine is facing increasing challenges in the region, e.g., biotic damage of unknown origin, increasingly arid site conditions. | Revenue from timber is lower and appears later. Production risk during management beyond final felling age, e.g., impacts of climate change, self-thinning, biotic and abiotic damage. | Significant loss of value in timber; after mortality occurs, the project terminates, and no further carbon credit revenue is generated. | Decrease in naturalness. According to the CRCF regulation, not eligible for carbon farming projects. | Currently limited timber marketing opportunities; industrial utilization is not resolved. | In the initial stage of management, carbon market revenue is low due to slow growth. |

| Scenarios | Stand Viability | Economic Potential | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regeneration | Survivability | Rotation Period | Production Value | |

| Scenario 1: Harvest and regeneration | + | − | + | ++ |

| Scenario 2: Extended rotation | − | − | n.r. | − |

| Scenario 3: Failed extended rotation | ||||

| Scenario 4: Conversion to Black locust | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Scenario 5: Conversion to Grey poplar | ++ | ++ | + | − |

| Scenario 6: Conversion to Turkey oak | + | ++ | + | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borovics, Á.; Király, É.; Keserű, Z.; Schiberna, E. Balancing Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Through Forest Management Choices—A Case Study from Hungary. Forests 2025, 16, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111724

Borovics Á, Király É, Keserű Z, Schiberna E. Balancing Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Through Forest Management Choices—A Case Study from Hungary. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111724

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorovics, Ábel, Éva Király, Zsolt Keserű, and Endre Schiberna. 2025. "Balancing Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Through Forest Management Choices—A Case Study from Hungary" Forests 16, no. 11: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111724

APA StyleBorovics, Á., Király, É., Keserű, Z., & Schiberna, E. (2025). Balancing Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Through Forest Management Choices—A Case Study from Hungary. Forests, 16(11), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111724