Development and Performance Validation of a UWB–IMU Fusion Tree Positioning Device with Dynamic Weighting for Forest Resource Surveys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design and Theory

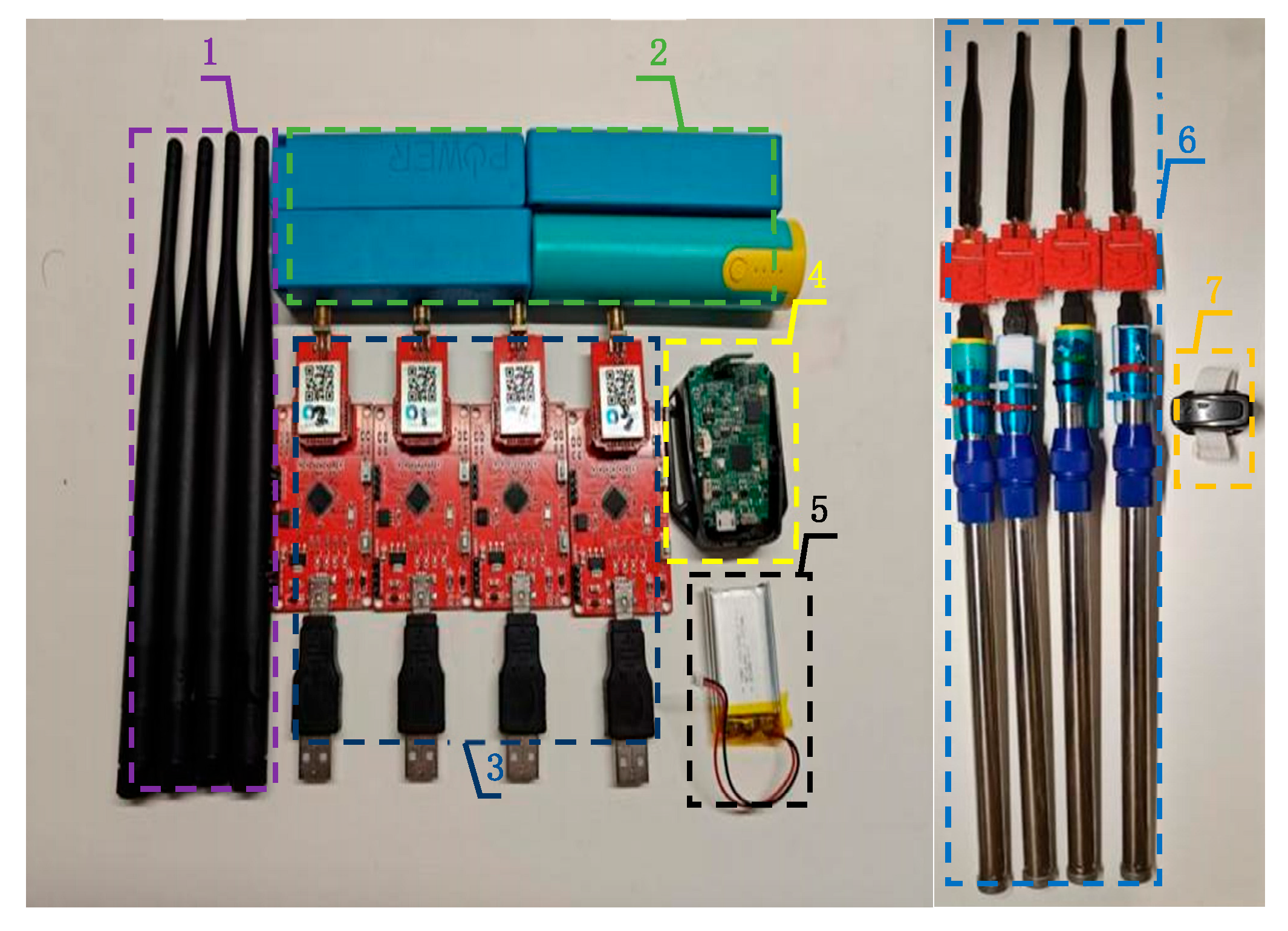

2.1. Device Design

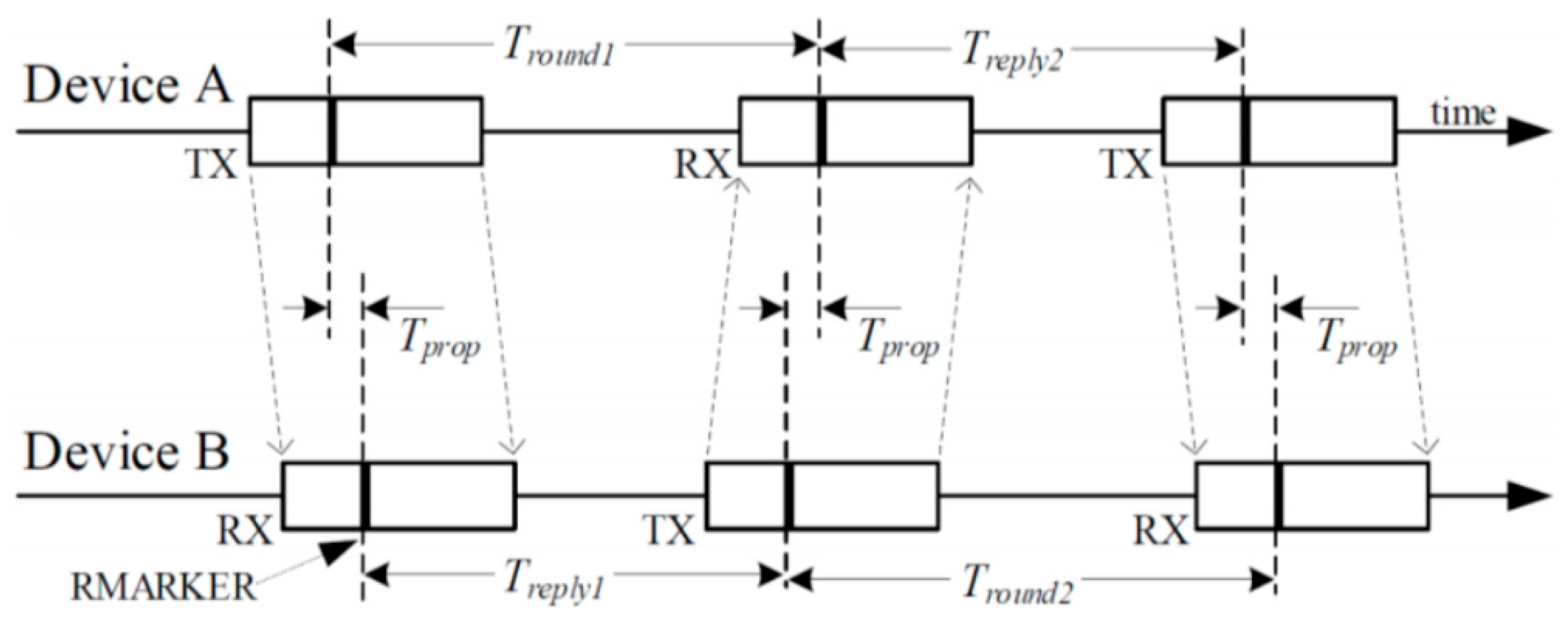

2.2. UWB Ranging Principle

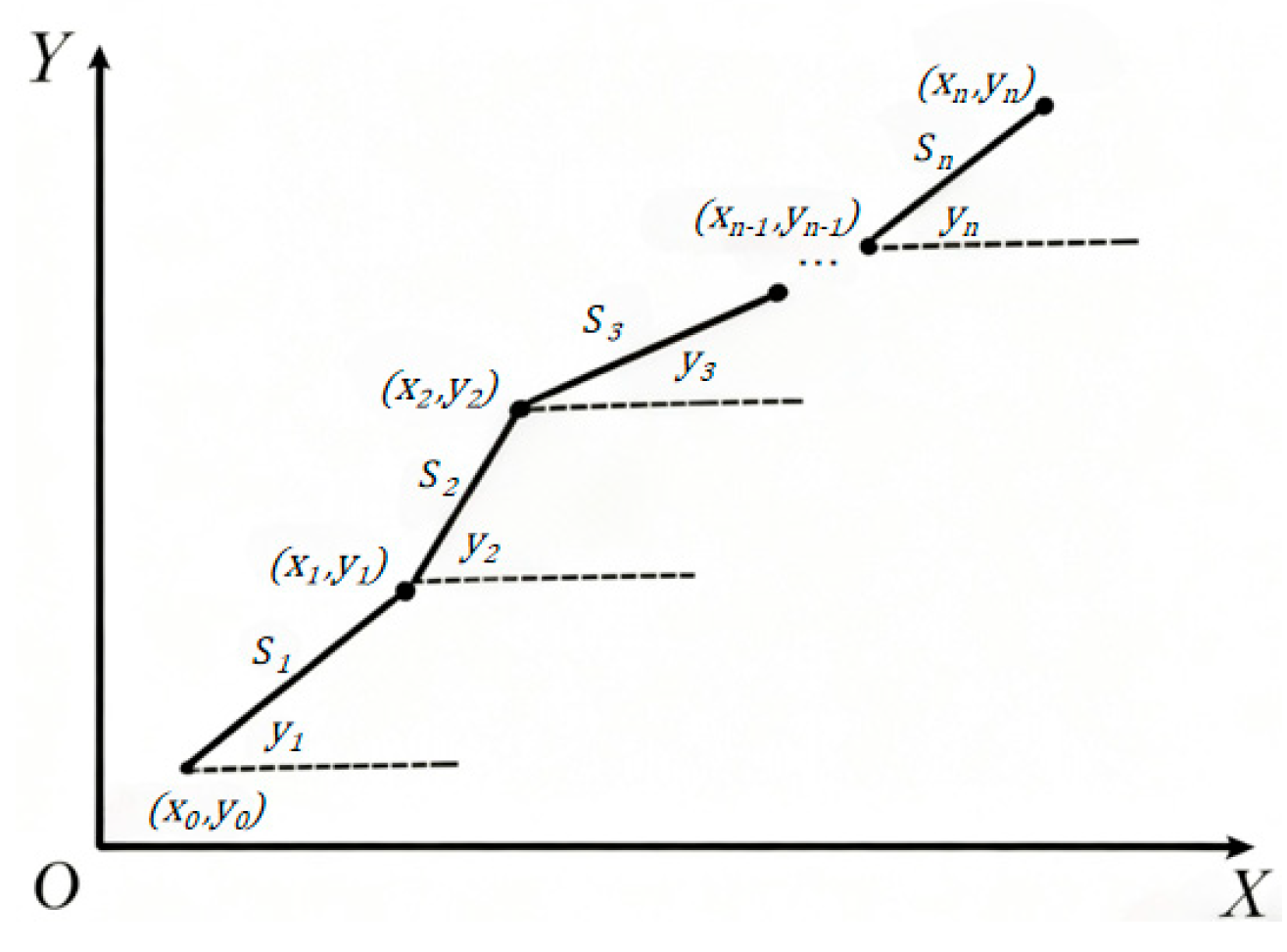

2.3. Inertial Navigation Ranging Principle

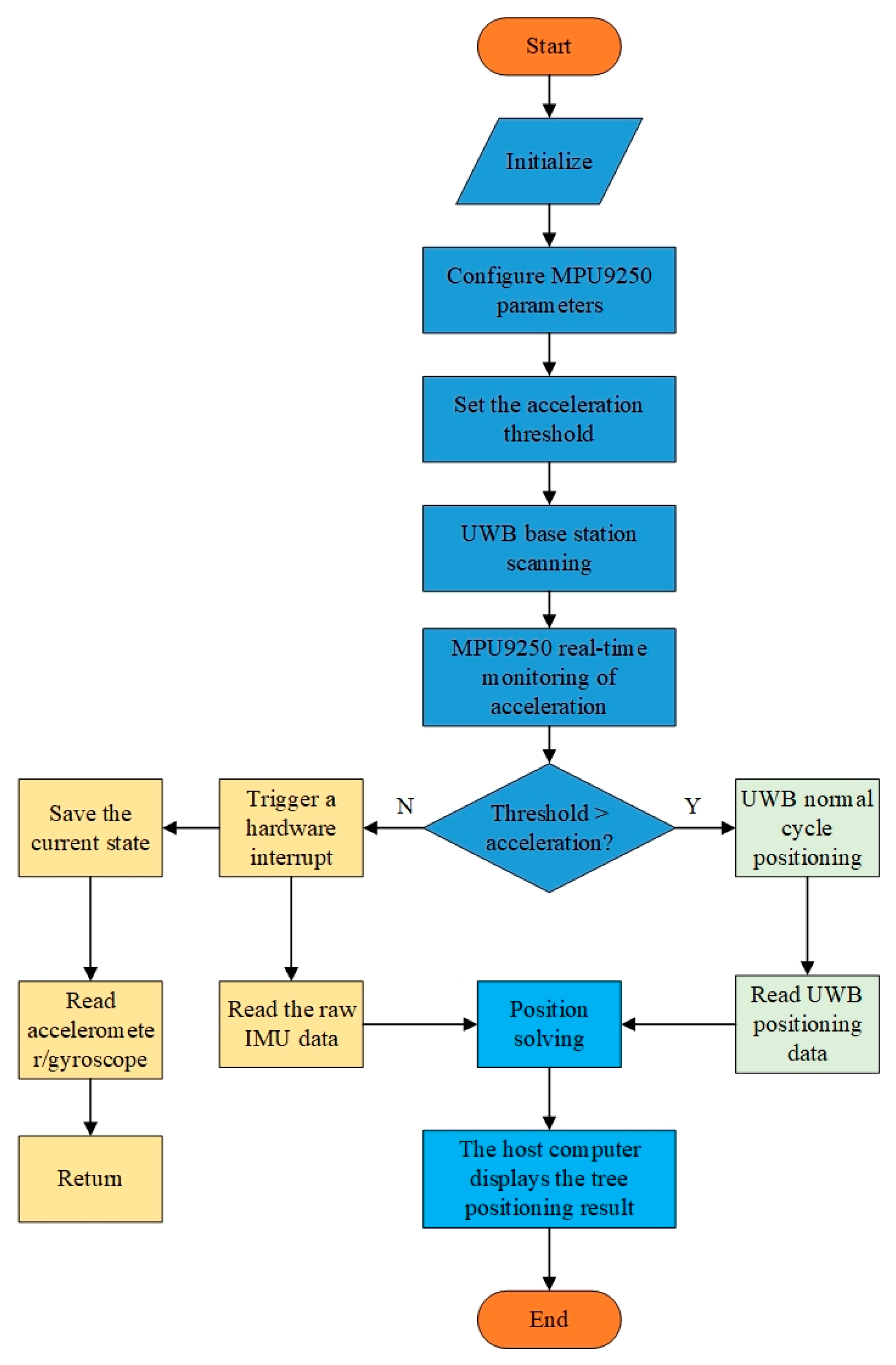

2.4. Combined UWB/Inertial Navigation Strategy

2.5. Determination of Dimensional Accuracy Limitations Post-Calibration

2.5.1. Static Test for Short-Range Limitations

2.5.2. Dynamic Test for Long-Range Limitations

2.5.3. Environmental Correction for Boundary Limitations

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Experimental Preparation

3.1.1. Core Criteria for Plot Selection

Gradient Coverage of Forest Structure

Terrain Condition Control

Representativeness of Interference Factors

3.1.2. Replication and Randomization Design

Repetitive Design

Randomization Method

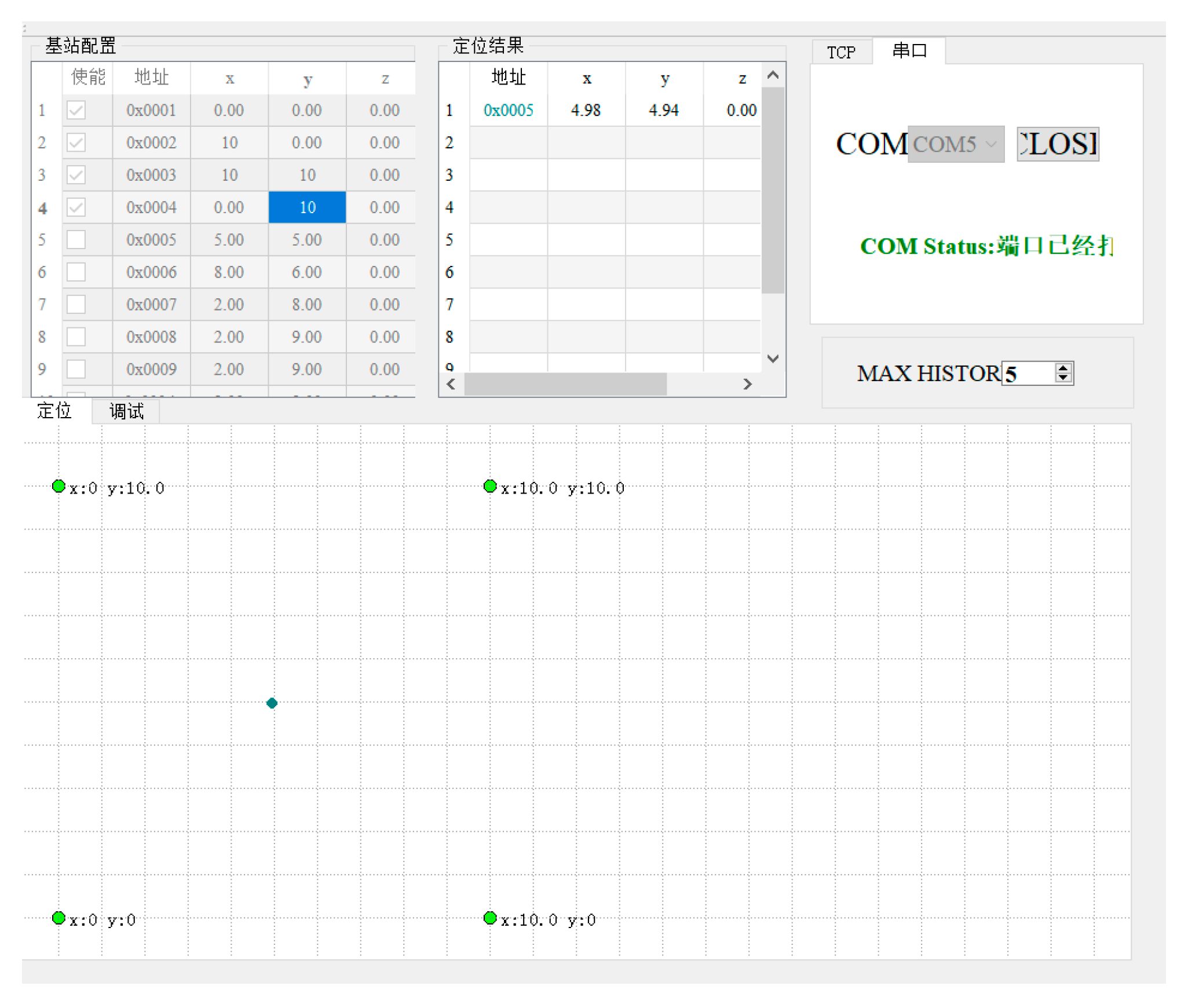

3.2. Base Station Deployment and Testing Process

3.2.1. Base Station Deployment

- Fix the four UWB modules on the top of the bracket and connect them to the mobile power supply, and assemble them into communication nodes A, B, C, and D.

3.2.2. Testing Process

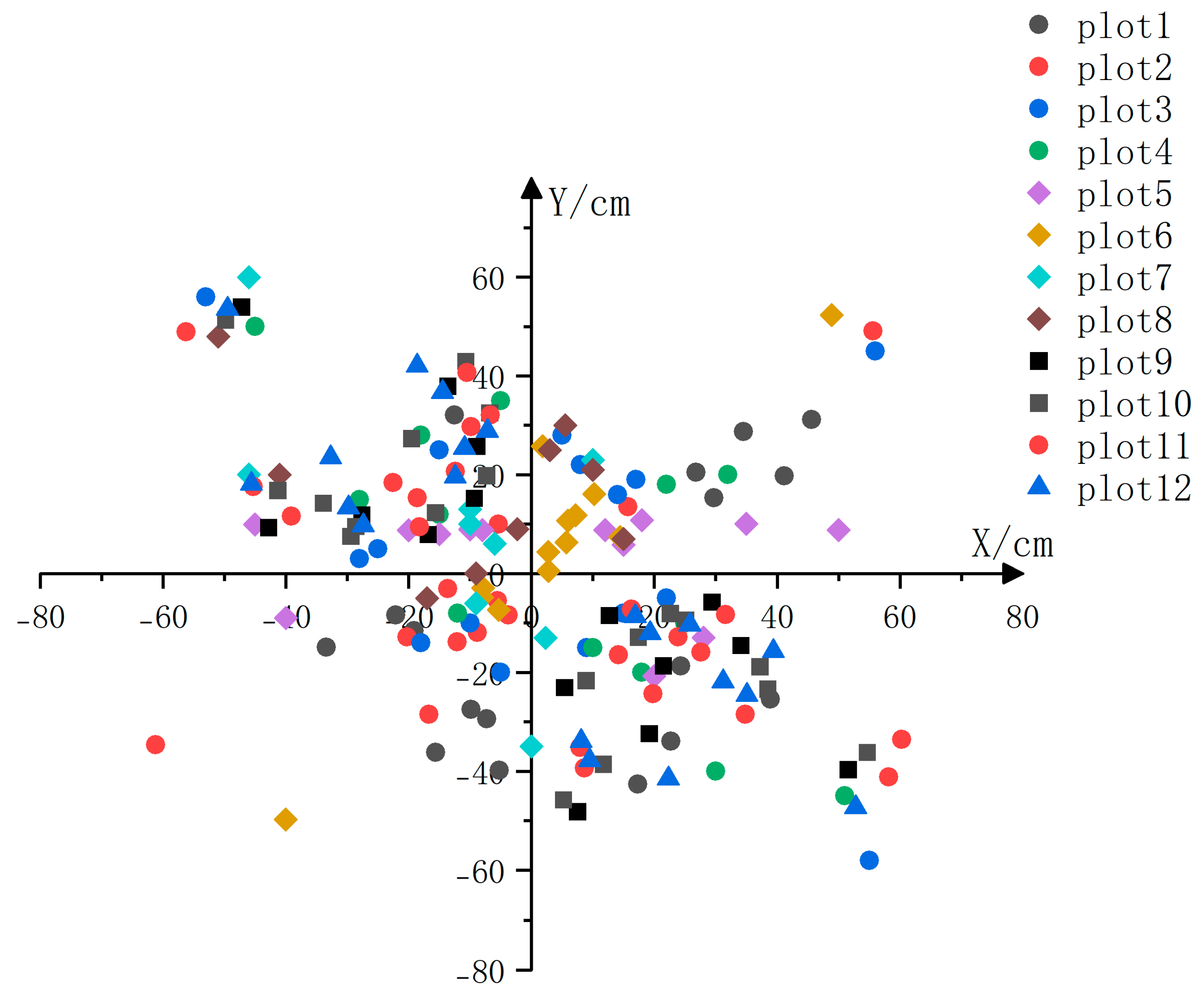

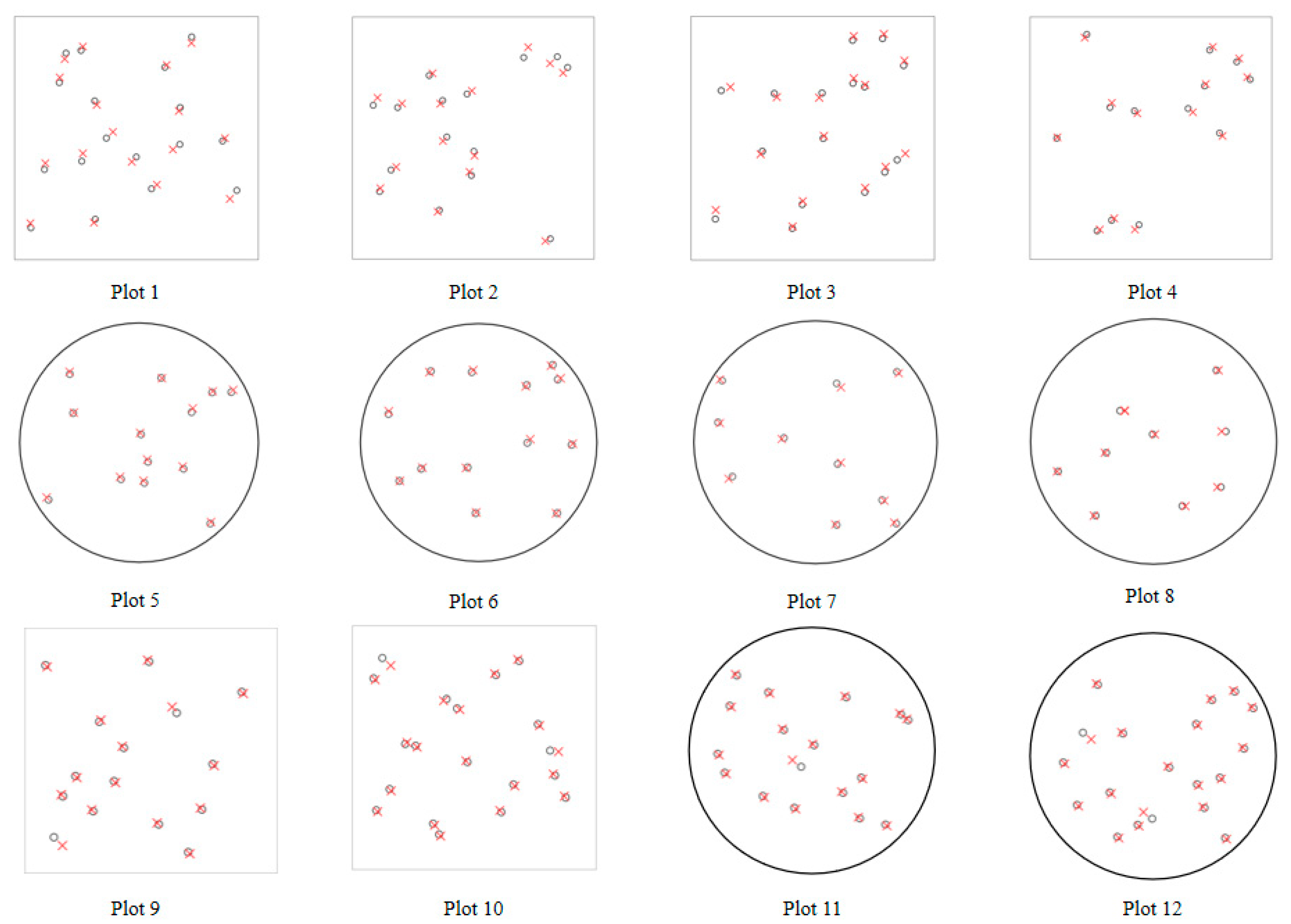

3.3. Tree Location Accuracy Assessment

4. Analysis of Results

4.1. Accuracy of Tree Locations

4.2. Efficiency of Positional Measurement

4.3. Specific Drawbacks of UWB/IMU Fusion Methods Under Environmental Factors

4.3.1. Impact of Humidity

- 1.

- UWB signal propagation delay caused by high atmospheric humidity

- 2.

- IMU Static Drift Amplified by High Soil Humidity

4.3.2. Impact of Leaf Water Content

- 1.

- UWB Multipath Interference Intensified by High Leaf Water Content

- 2.

- MU Temperature Drift Induced by Leaf Canopy Shading

5. Research Limitations

- Geographical and climatic restrictions: All tests were conducted in subtropical low-altitude forests (Lin’an District). Performance in temperate coniferous forests or high-altitude areas (>1000 m) remains untested, where low atmospheric pressure may affect UWB signal propagation [13].

- Extreme weather resistance: The device has not been validated in typhoons (wind speed > 25 m/s) or heavy snow, where base station displacement or antenna coverage could cause severe positioning failures [33].

- Battery and data compatibility: Short battery life (7.6 h) and lack of direct integration with forest GIS platforms (e.g., ArcGIS (v10.8)) limit large-scale application efficiency.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The multi-sensor fusion tree positioning equipment developed in this study enables the rapid and convenient measurement of tree positions, providing new ideas and methods for rapid measurement of tree spacing and positional relationship analysis in sample plots. The validation of four new groups of uneven-aged mixed forests shows that the device can adapt to complex forest stands with heterogeneous stand ages and diameters at breast height (DBH) spanning from 5 to 52 cm (the original maximum is 45 cm), further expanding the application scenarios of the technology. This adaptability to heterogeneous stands addresses the limitation of single-sensor technologies (e.g., pure UWB or IMU) that struggle to cope with diverse stand structures, as highlighted in previous studies on forest positioning [29,33]. Specifically, Zhang et al. (2025) noted that single-sensor solutions often fail to balance accuracy, whereas multi-sensor fusion can effectively mitigate this issue [33].

- (2)

- In terms of positioning accuracy, the UWB/IMU fusion solution has significant advantages, especially when compared with the pure UWB tree positioning technology proposed by Siqing Zheng et al. (2020) [22]. Zheng’s team conducted experiments in eight even-aged mixed forest plots, and their results showed that the average biases (BIAS) of tree position estimates in the X-axis and Y-axis directions were 0.99 cm and −3.78 cm, respectively; the root mean square errors (RMSE) were 19.86 cm and 23.44 cm, respectively; and the average straight-line distance error (Ed) of the eight plots was 27.43 cm, with a maximum of 84.07 cm and an average standard deviation of 13.93 cm [22]. In contrast, in the eight basic even-aged forest plots of this study, the X-axis BIAS was −1.54 cm, Y-axis BIAS was 1.27 cm; absolute values of biases were closer to 0, indicating smaller systematic errors than Zheng’s study. Although the X-axis RMSE (21.34 cm) in this study is slightly higher than Zheng’s 19.86 cm, the Y-axis RMSE (23.93 cm) is basically comparable to their 23.44 cm. More importantly, the average Ed of the eight basic even-aged plots in this study is 26.23 cm (lower than Zheng’s 27.43 cm), and the maximum Ed (76.52 cm) is significantly lower than their 84.07 cm, with a more concentrated error distribution. For the 12 test plots (including 8 original plots and 4 uneven-aged mixed forest plots), the overall X-axis BIAS ranges from −1.54 cm to −1.82 cm, Y-axis BIAS from 1.27 cm to 1.63 cm, X-axis RMSE from 21.34 cm to 24.51 cm, and Y-axis RMSE from 23.93 cm to 26.72 cm. The average Ed of the 12 plots is 26.87 cm, with a maximum error of 76.52 cm and a minimum of 2.83 cm. Compared with Zheng’s pure UWB scheme, the stability of this device is significantly improved, which is attributed to the dynamic weight fusion algorithm; when UWB signals are occluded (e.g., by dense branches and leaves in high-density stands), the algorithm increases the weight of IMU to compensate for UWB static errors, while using UWB to dynamically correct IMU cumulative errors, effectively solving the problem of large error fluctuations in pure UWB technology.

- (3)

- Terrain slope and tree density have a certain impact on positioning accuracy, and this effect is more pronounced in uneven-aged mixed forest plots: the average Ed of the four uneven-aged mixed forest samples (slope 15.6°~22.5°, plant spacing 2~3.5 m) is 3.16 cm higher than that of the original low slope homogeneous stand (slope 3.2°~12.3°), which is presumed to be due to the large shading area of the trunks of the old trees and the staggering of young trees’ crowns, resulting in the increase in UWB signal reflection. It is assumed that the large shading area of old-growth tree trunks and the interlacing of young-growth tree canopies resulted in an increase in the reflection of UWB signals. Meanwhile, it is also necessary to adjust the spacing of the base station in the high-density uneven-aged forests (currently at 10 m), so as to improve the adaptability of the device.

- (4)

- In the single-operator mode, the measurement time per tree is only 20.89 s, which is significantly more efficient than the traditional tape measure method (68.56 s per tree). The efficiency improvement is mainly due to automated data collection and processing, avoiding tedious manual recording and transcription. This aligns with the efficiency requirements of modern forest resource surveys, as Fan et al. (2018) [9] pointed out that rapid measurement technologies are essential for large-scale forest censuses, and manual methods (e.g., tape measures) can no longer meet the demand for timely data acquisition.

- (5)

- With regard to the adaptability of sample plots, the equipment can complete the data collection of round and square sample plots as well as the newly added uneven-aged mixed forest sample plots, the different shapes of the same plot and the structure of the forest stand do not have a significant effect on the positioning accuracy, the compatibility design significantly expands the application scenarios, and it can be adapted to sample plots setup with different survey specifications, thus providing a more flexible technological solution for the forest resources census.

- (6)

- Analysis of interference factors in uneven-aged mixed forest samples shows that understory vegetation cover and tree trunk shading contribute approximately 18.7% to positioning errors (15.2% in homogeneous forests). However, the dynamic weight fusion algorithm compensates for UWB signal loss by adjusting IMU weights (from 0.3 to 0.6 in static state), controlling error increase within 10%. This anti-interference ability is critical for practical forest surveys, as Wang et al. (2025) [29] emphasized that environmental interference (e.g., vegetation cover and terrain undulation) is unavoidable in real forests, and algorithms with adaptive interference mitigation are key to ensuring measurement reliability. Compared with Zheng et al.’s, (2020) [22] pure UWB technology, which is highly sensitive to signal occlusion, the proposed algorithm’s anti-interference performance further confirms its practical value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.R.; Lei, X.D.; Li, F. Research progress and prospects of forest management science in China. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2020, 56, 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.B. Forest inventory and analysis: A national inventory and monitoring program. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, S233–S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Fei, G.; Du, H. Application and precision analysis of several surveying methods in forest resources survey. J. Zhejiang For. Coll. 2009, 26, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Khan, T.U.; Nie, Z.; Yu, Q.; Feng, Z. Calibration and precise orientation determination of a gun barrel for agriculture and forestry work using a high-precision total station. Measurement 2021, 173, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, N.P.L.; Siu, T.Y.; Law, Y.K.; Zhang, H.; Sui, S.; Yip, F.T.; Ng, Y.S.; Ye, Y.; Cheung, T.C.; Wa, K.C.; et al. Mapping Individual Tree-and Plot-Level Biomass Using Handheld Mobile Laser Scanning in Complex Subtropical Secondary and Old-Growth Forests. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Mao, Q.; Wu, A.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Shi, Y. Beam vector model: A more applicable calibration method for terrestrial laser scanner. Measurement 2025, 254, 117814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Litkey, P.; Hyyppa, J.; Kaartinen, H.; Vastaranta, M.; Holopainen, M. Automatic stem mapping using single-scan terrestrial laser scanning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 50, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Application of Long Range Airborne LiDAR in Mapping High-density Vegetation Terrain in Mountainous Areas. Int. Core J. Eng. 2025, 11, 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Feng, Z.; Mannan, A.; Khan, T.U.; Shen, C.; Saeed, S. Estimating tree position, diameter at breast height, and tree height in real-time using a mobile phone with RGB-D SLAM. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.K.; Bae, T.S.; Kwon, J.H. An overview of a special issue on upcoming positioning, navigation, and timing: GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and BeiDou. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zong, Q.; Deng, X. Application analysis of GPS positioning technology and GIS based on metamaterial in forestry engineering. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 118, 03059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.G.; Cetin, E. Interference localization for satellite navigation systems. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliszek, D. GPS and Galileo Precise Point Positioning Performance with Tropospheric Estimation Using Different Products: BRDM, RTS, HAS, and MGEX. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oveland, I.; Hauglin, M.; Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E.; Maalen-Johansen, I. Automatic estimation of tree position and stem diameter using a moving terrestrial laser scanner. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Zhu, F.; Wu, S. Differential Code Bias Estimation and Accuracy Analysis Based on CSES Onboard GPS and BDS Observations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, W.; Li, M.; Jin, B. Single frequency service performance of BDSBAS: Models and assessment. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, T.; Yan, K.; Xie, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J. Two strategies to estimate inter-satellite link hardware delays in BDS-3 precise orbit and clock determination: Comparison and cross-check. J. Geod. 2025, 99, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, S.; Stahlke, M.; Feigl, T.; Seitz, J.; Thielecke, J. UWB channel impulse responses for positioning in complex environments: A detailed feature analysis. Sensors 2019, 19, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Cao, Z.; Chen, J.; Mu, Z. A Real-Time UWB Location and Tracking System Based on TWR-TDOA Estimation and a Simplified MPGA Layout Optimization. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 1194169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y. Uwb-based real-time 3d high precision localization system. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2290, 012082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fang, L.; Sun, Y.; Xia, L.; Lou, X. Development of measuring device for diameter at breast height of trees. Forests 2023, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Fang, L.; Sun, L.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J. Research on Tree Location Based on UWB Sensors. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2020, 2, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.M.; Zheng, Y. The study of the weighted centroid localization algorithm based on RSSI. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Wireless Communication and Sensor Network, Wuhan, China, 13–14 December 2014; pp. 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Carpi, F.; Martalò, M.; Davoli, L.; Cilfone, A.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ferrari, G. Experimental analysis of RSSI-based localization algorithms with NLOS pre-mitigation for IoT applications. Comput. Netw. 2023, 225, 109663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Lin, K.; Ren, A.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Rehman, M.U.; Yang, X.; Alomainy, A. RSSI indoor localization through a Bayesian strategy. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 25–26 March 2017; pp. 1975–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y. Installation Error Calibration Method for Redundant MEMS-IMU MWD. Micromachines 2025, 16, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, F. UWB-INS fusion positioning based on a two-stage optimization algorithm. Teh. Vjesn. 2025, 30, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zheleznov, V.M.; Kozlov, A.V.; Kuznetsov, A.G.; Molchanov, A.V.; Fomichev, A.V. Guaranteeng domains of sins instrumental errors. Teor. Sist. Upr. 2025, 2, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Dai, P.; Xu, T.; Nie, W.; Cong, Y.; Xing, J.; Gao, F. Maximum Mixture Correntropy Criterion-Based Variational Bayesian Adaptive Kalman Filter for INS/UWB/GNSS-RTK Integrated Positioning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, G. IMU data and GPS position information direct fusion based on LSTM. Sensors 2021, 21, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, B.; Fan, Y. Improved indoor positioning model based on UWB/IMU tight combination with double-loop cumulative error estimation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Luo, H.; Gao, X.; Liu, P. Fusion-Based Localization System Integrating UWB, IMU, and Vision. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, F.; Shu, L.; Wang, J. An integrated positioning method with IMU/UWB based on geometric constraints of foot-to-foot distances. Measurement 2025, 242, 115771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Component | Chip Interface/Type | Interface Type | Quantity | Parameter | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microprocessor | STM32F103 (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) | IO port, IIC, etc. | 5 | Flash: 128 KB | Data processing |

| Gyroscope module | MPU9250 (TDK InvenSense, San Jose, CA, USA) | Serial port | 1 | 9-axis data acquisition | Output raw sensor data |

| UWB module | D-DWM-PG1.7 (Decawave, Dublin, Ireland) | Serial port | 5 | measurement range: 0–400 m | Distance measurement |

| Battery | li-ion battery | Storage of electrical energy | 1 | 3000 mA | Power supply |

| Rechargeable battery | TP4056, SY7088, li-ion battery (Seiko Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) | USB-A/USB-C | 4 | 5V/2A | Storage of electrical energy |

| System Component | Module | Power Consumption (Standby) | Power Consumption (Working) | Power Consumption (Data Transmission) | Operating Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base station | UWB node (1 unit) | 0.15 W | 0.8 W | 1.2 W | - |

| 4 UWB nodes (total) | 0.6 W | 3.2 W | 4.8 W | - | |

| Antenna | 0.05 W | 0.05 W | 0.05 W | - | |

| Total base station | 0.65 W | 3.25 W | 4.85 W | 22 h (working state)/72 h (standby state) | |

| Mobile station | UWB module | 0.1 W | 0.6 W | 0.9 W | - |

| MPU9250 (TDK InvenSense, San Jose, CA, USA) | 0.08 W | 0.2 W | 0.2 W | - | |

| STM32F103 (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) | 0.05 W | 0.15 W | 0.2 W | - | |

| Handheld display | 0.2 W | 0.5 W | 0.5 W | - | |

| Total mobile station | 0.43 W | 1.45 W | 1.8 W | 7.6 h (working state)/25.8 h (standby state) | |

| System total | - | 1.08 W | 4.7 W | 6.65 W | - |

| Sample Size | Number of Trees/Plant | Main Species | Slope/(°) | Stand Type | Age Group Structure (Young: Medium: Mature Wood) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | A1, A2 | 3.2 | even-aged mixed forest | 1:9:0 |

| 2 | 15 | A3, A5 | 5.7 | even-aged mixed forest | 0:9:1 |

| 3 | 16 | A4, A7 | 6.3 | even-aged mixed forest | 1:9:0 |

| 4 | 13 | A6, A8 | 12.3 | even-aged mixed forest | 1:9:0 |

| 5 | 15 | A1, A4, A6 | 8.1 | even-aged mixed forest | 0:1:9 |

| 6 | 14 | A2, A5, A7 | 13.8 | even-aged mixed forest | 1:9:0 |

| 7 | 10 | A3, A8 | 18.9 | even-aged mixed forest | 0:9:1 |

| 8 | 9 | A1, A3, A5, A7 | 9.3 | even-aged mixed forest | 1:9:0 |

| 9 | 15 | A1, A3, A6 | 7.5 | uneven-aged mixed forests | 3:4:3 |

| 10 | 19 | A2, A5, A7, A8 | 11.2 | uneven-aged mixed forests | 4:3:3 |

| 11 | 17 | A3, A4, A5 | 9.8 | uneven-aged mixed forests | 2:5:3 |

| 12 | 20 | A4, A7, A8 | 13.1 | uneven-aged mixed forests | 3:4:3 |

| Sample Size | X/cm | Y/cm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIAS | RMSE | BIAS | RMSE | |

| 1 | −8.20 | 15.52 | 6.52 | 18.81 |

| 2 | 9.81 | 28.22 | −7.53 | 31.52 |

| 3 | −1.52 | 20.11 | 0.84 | 22.73 |

| 4 | 0.52 | 22.06 | 3.06 | 24.33 |

| 5 | −4.01 | 17.67 | 8.84 | 20.12 |

| 6 | 3.22 | 26.38 | −4.22 | 28.01 |

| 7 | −0.82 | 20.55 | 1.54 | 23.53 |

| 8 | −1.03 | 21.62 | −3.51 | 25.57 |

| 9 | −2.13 | 22.85 | −1.96 | 24.72 |

| 10 | −4.05 | 25.51 | −4.88 | 27.36 |

| 11 | 1.87 | 19.93 | 0.54 | 22.89 |

| 12 | −2.35 | 21.76 | 1.92 | 23.85 |

| add up the total | −1.69 | 20.87 | 1.03 | 22.79 |

| Sample Size | Ed/cm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Max | Min | Std | |

| 1 | 28.12 | 48.23 | 7.03 | 8.53 |

| 2 | 23.83 | 76.52 | 11.24 | 18.14 |

| 3 | 19.43 | 68.01 | 14.77 | 9.74 |

| 4 | 26.02 | 68.93 | 10.34 | 13.95 |

| 5 | 27.03 | 58.34 | 9.53 | 12.35 |

| 6 | 24.14 | 54.25 | 1.83 | 14.06 |

| 7 | 33.36 | 65.47 | 8.85 | 15.78 |

| 8 | 26.95 | 58.63 | 5.56 | 14.87 |

| 9 | 27.59 | 72.38 | 2.81 | 13.65 |

| 10 | 29.12 | 75.82 | 2.37 | 14.82 |

| 11 | 22.87 | 66.55 | 3.19 | 11.43 |

| 12 | 25.02 | 69.73 | 3.56 | 12.66 |

| add up the total | 25.15 | 75.82 | 2.37 | 12.89 |

| Measurement Method | Necessary (For) Number of Persons | Single Wood Measurement Number of Measurements/Times | Total Time Consumption /s | Average Single Wood Time/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positioning equipment | 1 | 1 | 3781.09 | 20.89 |

| tape measure | 2 | 1 | 12,409.36 | 68.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, Z.; Sun, L.; Xu, A.; Yao, H.; Fang, L. Development and Performance Validation of a UWB–IMU Fusion Tree Positioning Device with Dynamic Weighting for Forest Resource Surveys. Forests 2025, 16, 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111703

Cui Z, Sun L, Xu A, Yao H, Fang L. Development and Performance Validation of a UWB–IMU Fusion Tree Positioning Device with Dynamic Weighting for Forest Resource Surveys. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111703

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Zongxin, Linhao Sun, Ao Xu, Hongwen Yao, and Luming Fang. 2025. "Development and Performance Validation of a UWB–IMU Fusion Tree Positioning Device with Dynamic Weighting for Forest Resource Surveys" Forests 16, no. 11: 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111703

APA StyleCui, Z., Sun, L., Xu, A., Yao, H., & Fang, L. (2025). Development and Performance Validation of a UWB–IMU Fusion Tree Positioning Device with Dynamic Weighting for Forest Resource Surveys. Forests, 16(11), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111703