Abstract

Driven by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the global “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative, China has become a key bamboo industry player by leveraging abundant resources and an integrated supply chain. To enhance international competitiveness, optimizing product structure and market resilience is essential. Using descriptive statistics, visualization, trade concentration index, and K-means clustering, this study analyzed China’s bamboo trade spatiotemporal patterns and market resilience based on 2015–2024 China customs data. Results revealed major revisions in the Harmonized System (HS) codes for bamboo products in 2017, yet existing classifications remain insufficiently detailed. Imports declined overall, characterized by fragmented primary products mainly sourced from the Taiwan region of China and Vietnam. In contrast, exports grew steadily, led by Bamboo Tableware, with the United States, Japan, and Europe as key markets, and notable expansion into Southeast Asia. In 2024, bamboo products accounted for over 99% of China’s total bamboo trade value, and the export–import gap kept widening. Compared with 2015, export concentration declined: low- and medium-concentration markets increased, highly concentrated ones decreased, and overall resilience improved. Cluster analysis split core destinations into seven groups in 2015 but only five in 2024, signalling broader demand diversity and fewer single-category-dominated markets. The study recommends refining HS codes to reflect new bamboo innovations; consolidating markets in Europe and America while expanding differentiated demand in Southeast Asia; upgrading Bamboo Tableware through technology; and boosting core product competitiveness to support global bamboo trade and the “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative.

1. Introduction

Bamboo plays a vital role in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including climate action (SDG 13) [1], biodiversity conservation (SDG 15), sustainable consumption and production patterns (SDG 12), poverty alleviation (SDG 1), and rural development [2,3,4]. Recognized by the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization (INBAR) as a strategically important resource, bamboo contributes significantly to global sustainability agendas [5]. The European Union’s 2015 regulation on reducing single-use plastic bags created substantial market opportunities for eco-friendly and biodegradable bamboo products, reinforcing the sector’s role in sustainable consumption (SDG 12) [6]. In November 2022, the Chinese government, in collaboration with INBAR, launched the “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative, highlighting bamboo’s potential as a nature-based solution [7]. To operationalize the initiative, the National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NDRC), the National Forestry and Grassland Administration of the People’s Republic of China (NFGA), and other ministries issued several strategic documents, including the “Three-year Action Plan to Accelerating the Development of Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic”, “Guidelines for Accelerating Innovation and Development of Bamboo Industry” and “Specialized Standard System for Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic”, aiming to foster high-quality development of the bamboo industry.

China, holding one of the richest bamboo resources globally, is a leading producer, consumer, and exporter of bamboo products [8,9]. Under the initiative, the Chinese bamboo industry is undergoing profound transformation, forming an integrated value chain that includes cultivation, harvesting, processing, research and development, and trade, following the concept of “whole bamboo utilization” [10]. Internationally, countries like India and Indonesia also possess rich bamboo resources and emphasize the development of the bamboo industry. India launched a comprehensive bamboo development program in 1999, aiming to promote the bamboo sector, create jobs, and reduce poverty, while highlighting the role of bamboo in industries such as construction and furniture production [11]. Indonesia, on the other hand, views bamboo as an important economic and environmental resource, widely used in soil conservation, water management, and greenhouse gas absorption [12]. The bamboo industry, as a sustainable resource, is increasingly gaining attention from countries around the world, driving progress in green economy and environmental protection.

Existing research on bamboo trade primarily focuses on four areas: trade scale, structure, influencing factors, and future trends. Regarding trade scale, global bamboo trade demonstrates steady growth, primarily concentrated in Asia, Europe, and North America [13]. In terms of trade structure, China remains the largest exporter of bamboo products, forming a star-shaped global trade network centered around China [14,15,16]. Studies on influencing factors indicate significant roles for economic scale, transportation costs, and forest resource endowments in shaping China’s bamboo and rattan product trade flows [17,18]. Future developmental trends suggest that, while maintaining traditional competitive advantages, China’s bamboo industry must confront the challenges of transitioning from resource-based to technology-driven sectors and from traditional handicrafts to advanced industrial products [19]. Advancing industrial competitiveness requires technological breakthroughs, policy guidance, standard refinement, market promotion, and policy support, thus fostering high-end industrialization and intelligent manufacturing [20,21]. However, existing research in the field of bamboo product trade still has significant gaps: First, previous macro-focused studies overlook the evolution of Harmonized System (HS) codes (Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System) and spatio-temporal product categorization. Second, qualitative trade structure analyses lack quantitative frameworks for measuring market concentration and resilience. Third, research on the differentiated characteristics of regional markets and demand preferences remains significantly inadequate.

This study aims to examine the evolution of import-export trade characteristics and assess the resilience of export markets for China’s bamboo products, based on trade data from 2015 to 2024. Its contributions are fivefold: First, systematically reviewing temporal changes in HS code to elucidate the evolution of bamboo product classification systems in international trade, enhancing the clarity and optimization of China’s import-export management practices. Second, employing time-series analysis of import-export value and trade product composition to reveal supply capability dynamics and the evolving supply-demand interactions between China and its major trade partners. Third, examining changes in trade partner distribution and trade value to identify expansions or contractions in China’s bamboo export markets, reflecting international demand fluctuations and trade environment uncertainties, thus supporting strategic decision-making. Fourth, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) was introduced to quantitatively assess structural differences in China’s major bamboo product export markets between 2015 and 2024, providing a detailed evaluation of market concentration dynamics, and offering empirical evidence for optimizing export market distribution and enhancing international competitiveness. Fifth, K-means clustering was applied to categorize key export markets in 2015 and 2024 into “diverse demand markets” and “single-category dominant markets,” systematically identifying and tracking shifts in market demand preferences. This research provides crucial insights into optimizing China’s bamboo industry strategies, facilitating global bamboo resource utilization, supporting sustainable development, and effectively advancing the “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The geographical scope of this study encompasses China and its international trade partners involved in bamboo product exchanges. China is one of the earliest countries to recognize, cultivate, and utilize bamboo, leading globally in bamboo species, growing area, and reserves [22,23]. According to data from the Third National Land Survey, China hosts 837 bamboo species across 39 genera, accounting for approximately 51% of the world’s 1642 recognized bamboo species [24,25]. According to the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the global area of bamboo forests reached 35.04 million hectares in 2020 [26]. China accounted for approximately 6.42 million hectares, representing 18.30% of the global total [27]. Concentrated in Fujian, Jiangxi, and Hunan provinces, this abundant resource base underpins the vigorous growth of China’s bamboo industry.

Spanning primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, China’s bamboo industry boasts diverse products and leads globally in scale, output, and trade [28]. Its output rose from CNY 59.76 billion (2008) to CNY 412.33 billion (2022) [29,30], with a 14.79% average annual growth rate and 590.01% cumulative growth. In terms of trade, 2024 bamboo product trade totaled CNY 16.62 billion (up 1.75% year-on-year). In 2022, exports reached CNY 16.58 billion (99.73% of total trade) versus imports of CNY 45 million (0.27%), creating a CNY 16.53 billion surplus. As the world’s top bamboo product exporter, China’s 2022 exports accounted for 75.1% of the global total [13], highlighting its dominant international position.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Trade Concentration Analysis

This study employs the HHI to assess the trade concentration of bamboo products, as shown in Equation (1). The HHI is widely used to quantify the degree of concentration or diversification in a country’s trade structure for specific product categories [31,32,33].

where represents the share of the i-th product category in the total trade value of country j, and nnn denotes the total number of product categories. The HHI ranges from to 1. A higher HHI value suggests a more concentrated trade structure, dominated by a few product categories, while a lower HHI value implies a more diversified and evenly distributed trade portfolio. To classify trade partners by their trade concentration levels, we adopt a standardized threshold framework from Statistics Canada [34]:

Low concentration: HHI < 0.15

Moderate concentration: 0.15 ≤ HHI < 0.25

High concentration: HHI ≥ 0.25

2.2.2. K-Means Cluster Analysis

To further explore market heterogeneity, this study aims to classify trade partners based on their product preference profiles, selecting K-means clustering [35,36]. The selection of this method is primarily based on its efficiency and interpretability in high-dimensional data analysis—it can quickly and accurately group trade partners, with intuitive and easy-to-understand clustering results that facilitate subsequent analysis and policy formulation [37,38].

K-means clustering aims to partition the dataset into K clusters by minimizing the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) within each cluster, as defined in Equation (2):

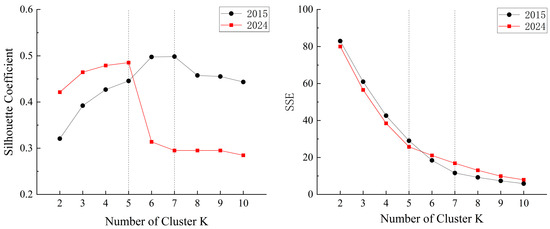

where x is a data point, is the centroid of cluster , and the Euclidean distance is calculated as: . Here, d represents the number of features, is the j-th attribute of sample x, and is the j-th attribute of centroid . To determine the optimal number of clusters K, we adopt two widely accepted methods: (1) Elbow Method: Identifies the point at which adding additional clusters no longer significantly reduces the SSE, thus indicating the most suitable K value. (2) Silhouette Method: Evaluates clustering quality by balancing intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation [39,40]. These two methods are combined to select the optimal K value. the Silhouette Method is used to select candidate K values that exhibit a high average silhouette coefficient and meet the threshold criterion, followed by the Elbow Method to validate whether the selected K value corresponds to the point at which the reduction in SSE significantly slows down. These methods are employed collaboratively to identify the optimal K value. Furthermore, the validity of the clustering results is assessed by integrating the original data with the structural characteristics of China’s international trade in bamboo products.

Given the high dimensionality of the dataset, which consists of seven original variables, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied prior to clustering to reduce dimensionality and mitigate multicollinearity, thereby improving computational efficiency and robustness. Components were retained until the cumulative variance contribution exceeded 85%, ensuring key informational content was preserved while minimizing redundancy [41]. This dimensionality reduction provides a reliable foundation for subsequent clustering analysis.

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

The trade data on bamboo products used in this study were sourced from the database of the General Administration of Customs of China [42]. All data are denominated in Chinese Yuan (CNY) and have been standardized by the General Administration of Customs, thus eliminating the need for multi-currency conversion and avoiding issues related to exchange rate fluctuations. In accordance with the statistical scope and classification standards for China’s import and export trade [43], the Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan regions of China are treated as separate trade partner regions. Accordingly, goods exchanged between mainland China and these three regions are included in the country’s foreign trade statistics. Therefore, references to “China” throughout this study specifically denote mainland China, excluding the Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan regions. To ensure statistical consistency, this study uses the current HS coding system as the statistical basis. Notably, a significant revision of HS codes in 2017 led to changes in the names and codes of some bamboo products, resulting in partial data gaps between periods before and after 2017. To address this, we have systematically reconciled bamboo product records affected by HS code revisions or product name adjustments between 2015 and 2024 (with data under old codes aggregated and mapped to the current HS framework) to avoid discrepancies arising from coding changes, thereby enhancing the rigor and validity of the research data. Additionally, to maintain the integrity of trade partner analysis, records with “unknown country or region” designations [42]—present in import data between 2015 and 2020—were excluded when calculating the number of trade partners due to incomplete geographic identification. This measure ensures the robustness and credibility of the findings presented in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of China’s Bamboo Product Import-Export Trade Characteristics

3.1.1. Classification System and Evolution of HS Codes for Bamboo Products

This study adopts the internationally standardized HS code as the statistical framework. Trade data were retrieved from the General Administration of Customs of China database (http://stats.customs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 July 2025)). During data retrieval, the “output field group” was set to “commodity” and the keyword “bamboo” was entered under the “8-digit code” option. Based on this method, 37 bamboo-related product categories were identified under the current HS coding system, which were subsequently grouped into seven categories according to their functional attributes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of Bamboo Products.

An analysis of HS code revisions for bamboo products since 2015 shows that 2017—a key year for China’s HS code updates—saw significant changes: four new codes (44187310, 44191100, 44191290, 44219190) were added and ten product codes or descriptions modified, reflecting the growing diversification of bamboo products, with the 2017-introduced residual code 44219110 (“Other bamboo products, not elsewhere specified”) facilitating the statistical inclusion of emerging categories. However, as the bamboo industry develops—particularly with the emergence of innovative “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” products—the existing HS coding system, despite partial coverage, lacks sufficient granularity and fails to fully adapt to evolving product types and applications. Thus, further refining the HS coding framework (with reference to the “Key Promotion Catalogue of Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic Achievements” [44]) to accurately classify and statisticize emerging bamboo products has become critical for promoting the industry’s sustainable development.

3.1.2. Trends in Trade Value

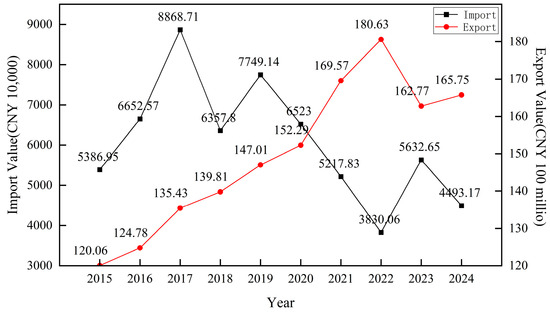

A macro-level analysis of China’s bamboo product trade from 2015 to 2024 (Figure 1) shows distinct trends for imports and exports. Imports exhibited significant year-to-year fluctuations with an overall downward trend, declining from CNY 53.87 million in 2015 to CNY 44.93 million in 2024, a 16.58% decrease. The highest import value was recorded in 2017 (CNY 88.69 million), while the lowest was in 2022 (CNY 38.30 million), reflecting a 56.81% range of fluctuation. This downward trend in fluctuations reflects the continuous improvement of China’s bamboo industry’s self-supply capacity, with domestic bamboo resource cultivation and processing capacity gradually meeting market demand, thereby reducing reliance on imported bamboo products [45].

Figure 1.

Import and Export Trade Value from 2015 to 2024.

In contrast, exports showed a consistent upward trajectory, increasing by 38.06% from 2015 to 2024, peaking in 2022 at CNY 18.06 billion. This growth coincides with intensified “plastic restriction” policies initiated by the EU, the United States, Japan, and South Korea [6,46]. As demand for sustainable alternatives to plastic surged, bamboo—valued for its eco-friendliness and versatility—emerged as a preferred substitute, fueling export growth. However, a decline in 2023 signals the need for further improvements in product diversification and market development to counter global demand fluctuations and emerging trade barriers.

A comparison of the import and export trade trends reveals an overall pattern of “shrinking imports, expanding exports, and a widening gap between the two,” which intuitively reflects the export resilience of China’s bamboo industry. In 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread disruptions to global supply chains [47], yet China’s foreign trade maintained a positive momentum amid the pandemic [48]. The export of Chinese bamboo products not only continued its growth trend, but also saw a further acceleration in the growth rate in 2021 and 2022. This growth highlights the urgent demand for such eco-friendly bamboo products in the current global green transition process, effectively enhancing the strong risk resistance and sustainable development resilience of China’s bamboo product trade.

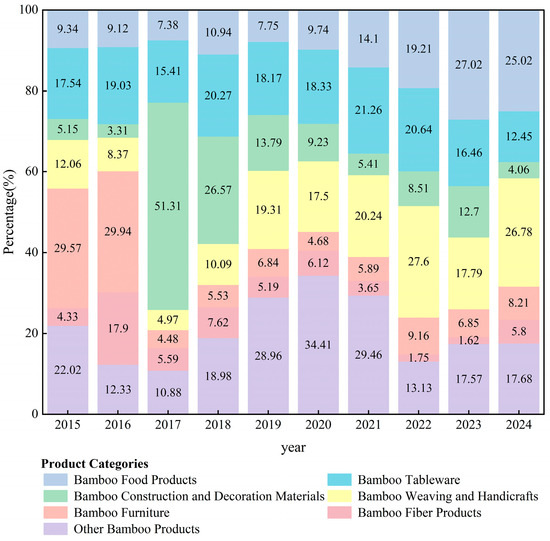

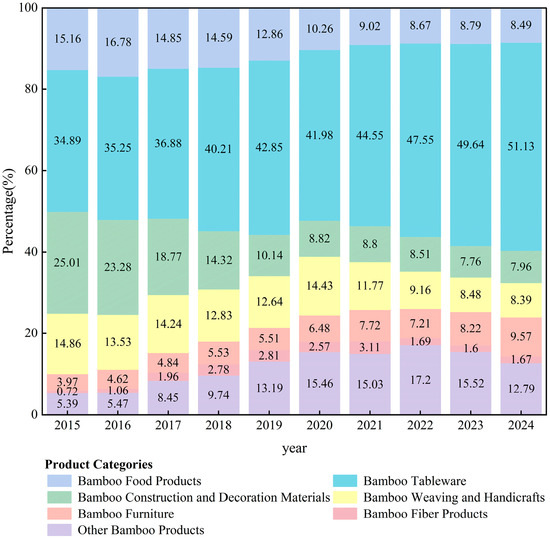

3.1.3. Analysis of Trade Product Composition

From 2015 to 2024, the composition of bamboo imports and exports diverged significantly (Figure 2 and Figure 3), based on the classification of bamboo products presented in Table 1. On the import side, Bamboo Food Products and Bamboo Weaving and Handicrafts items account for a large share and show an upward trend, with their proportions increasing by 15.68% and 14.72%, respectively, from 2015 to 2024. Meanwhile, the proportion of imports of Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials and Bamboo Fiber Products has gradually declined. Notably, the proportion of Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials dropped from 51.31% in 2017 to only 4.06% in 2024. This shift reflects that the domestic market’s demand for Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials has gradually turned to domestic supply or alternatives and also indicates that China’s self-reliance capacity in the field of Bamboo Fiber Products has improved.

Figure 2.

Import Proportion of Various Bamboo Products from 2015 to 2024.

Figure 3.

Export Proportion of Various Bamboo Products from 2015 to 2024.

On the export side, Bamboo Tableware became the dominant category, rising from 34.89% of exports in 2015 to 51.13% in 2024. This surge aligns with the global Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic movement and the inclusion of Bamboo Tableware as a key product in China’s Three-year Action Plan to Accelerating the Development of Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic [49]. Simultaneously, exports of Bamboo Food Products, Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials, and Bamboo Weaving and Handicrafts declined. Notably, Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials dropped from 25.01% in 2015 to 7.96% in 2024, a 17.05 percentage-point decrease. This trend may signal waning international demand or enhanced domestic production capabilities in those segments.

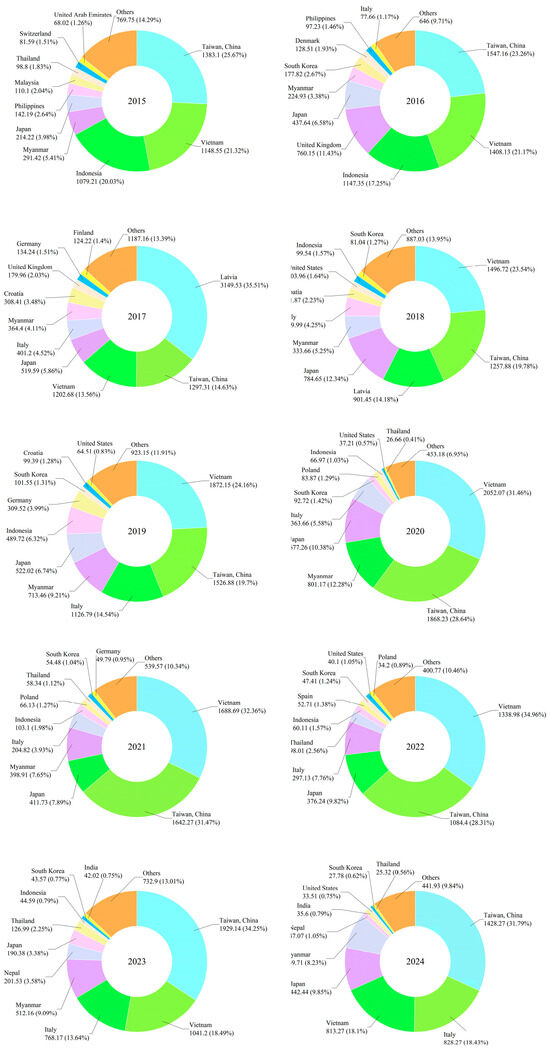

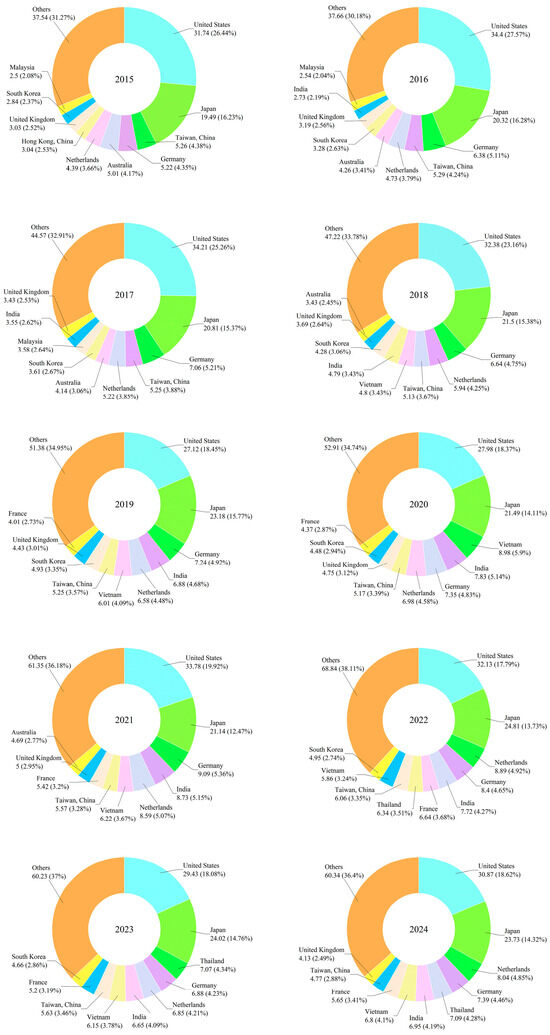

3.1.4. Market Composition of Major Trade Partners

Figure 4 and Figure 5 present China’s top ten bamboo product trade partners from 2015 to 2024 in terms of trade value and share. On the import side, China’s Taiwan, Vietnam, and Japan consistently ranked among the top three, collectively accounting for over 40% of imports with upward trends. Vietnam’s share peaked at 31.5% in 2020, while China’s Taiwan’s reached 31.8% in 2024, underscoring the strong competitive positions of these suppliers. In line with Figure 1, China’s bamboo product imports have shown a steady decline since 2015, reflecting not only the gradual enhancement of domestic production capacity but also a sustained reduction in reliance on imports. During this period, strengthened cooperation with major sourcing regions such as China’s Taiwan, Vietnam, and Japan has improved coordination within the import supply chain. This, in turn, has helped mitigate risks associated with fragmented import categories and enhanced processing efficiency across the industry.

Figure 4.

Top 10 Countries (Regions) by China’s Bamboo Product Import Value from 2015 to 2024. The labels in the donut charts indicate the import value (in CNY 10,000) and its share of total annual imports. The number at the center of each chart represents the year. For example, “Taiwan, China, 1383.10, 25.67%” in the 2015 chart indicates that mainland China imported bamboo products worth CNY 13.831 million from Taiwan, China, accounting for 25.67% of total bamboo imports that year.

Figure 5.

Top 10 Countries (Regions) by China’s Bamboo Product Export Value from 2015 to 2024. The labels in the donut charts indicate the export value (in CNY 100 million) and its share of total annual exports. The number at the center of each chart represents the year. For example, “United States, 31.74, 26.4%” in the 2015 chart indicates that China exported bamboo products worth CNY 3.174 billion to the United States in 2015, accounting for 26.4% of the total export value that year.

On the export side, the United States and Japan consistently held the top two positions over the past decade. European countries such as Germany, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, along with China’s Taiwan, also ranked in the top ten, forming a stable export market base (Figure 5). While the combined export value to the United States and Japan rose from CNY 5.12 billion in 2015 to CNY 5.46 billion in 2024, their market share declined from 26.44% and 16.23% to 18.62% and 14.32%, respectively. This trend indicates a diversification of export destinations despite increasing trade value. Germany, The Netherlands, and China’s Taiwan consistently maintained approximately 4% market shares, with limited annual fluctuations. India, Vietnam, and Thailand emerged as key export destinations in 2016, 2018, and 2022, respectively, and together accounted for 12.57% of exports in 2024, signaling the rise in emerging markets in South and Southeast Asia. The combined share of the top ten export markets declined from 68.73% in 2015 to 63.6% in 2024, reflecting a progressive diversification in China’s bamboo export market structure, which enhances the industry’s resilience to external shocks and improves adaptability to global market dynamics.

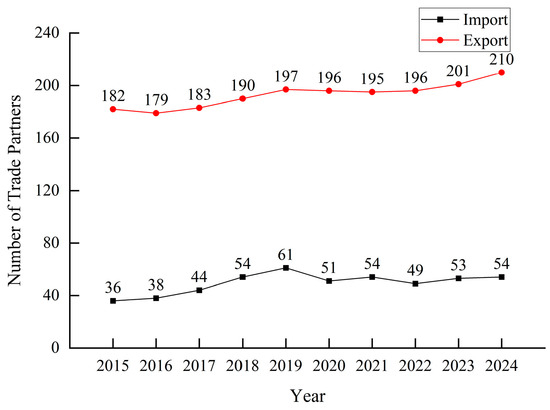

3.1.5. Changes in the Number and Geographic Distribution of Trade Partners

Since 2015, the annual number of China’s bamboo product trade partners has shown notable fluctuations (Figure 6), reflecting a clear trend toward import market stabilization and export market diversification. These dynamics underscore China’s evolving trade structure in the international bamboo product market. On the import side, the number of trade partners initially increased, peaking at 61 in 2019, but then gradually declined, stabilizing between 49 and 54 from 2020 to 2024. This trend suggests a growing stabilization of import sources. In contrast, export trade partners increased from 182 in 2015 to 210 in 2024, demonstrating a steady upward trajectory and indicating that China has largely completed a global layout of export trade relationships.

Figure 6.

Number of Import and Export Trade Partners from 2015 to 2024.

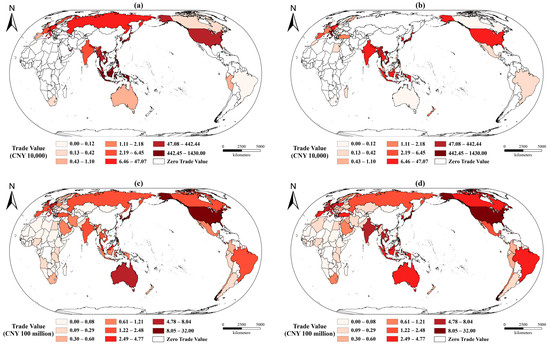

Heatmaps illustrate the spatial distribution of China’s import and export partners in 2015 and 2024 (Figure 7), with color intensity representing trade value. On the import side (Figure 7a,b), the primary sources of imports for Chinese bamboo products are concentrated in Asia, Europe, and North America, while the number of trade partners from Africa and South America has steadily increased. However, as shown in Figure 1, from 2015 to 2024, despite a downward trend in import trade value, the number of trade partners has overall increased. This can be attributed to two factors: on one hand, the deepening of the globalization process has facilitated increasingly frequent trade exchanges among countries; on the other hand, enterprises have actively expanded their import channels to ensure supply stability. Overall, despite the decline in import trade value, the number of trade partners remained stable from 2020 to 2024 (Figure 6), indicating that enterprises are more inclined to establish long-term partnerships with reliable suppliers. This trend reflects a rational result of market-driven choices and continuous supply chain optimization in response to the complex global trade environment.

Figure 7.

Distribution of China’s Bamboo Product Trade Partners in 2015 and 2024. (a) Imports in 2015; (b) Imports in 2024; (c) Exports in 2015; (d) Exports in 2024. The maps are based on the GS2020 (4403) standard map, obtained from the Standard Map Service of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (http://www.mnr.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 July 2025)). The base map was used without any modifications.

On the export side (Figure 7c,d), the geographic coverage of trade partners has expanded significantly, now encompassing most regions worldwide. Countries across Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Africa have maintained high levels of both trade value and partner count, confirming a steady global demand for Chinese bamboo products. This growth is largely driven by the eco-friendly nature of bamboo products and their alignment with the global “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative. Concurrently, innovations in bamboo processing technology and a marked increase in production capacity have enhanced China’s competitiveness. The diversification of export markets has also strengthened the industry’s resilience against international market fluctuations, providing a strong foundation for the sustainable and stable development of China’s bamboo sector.

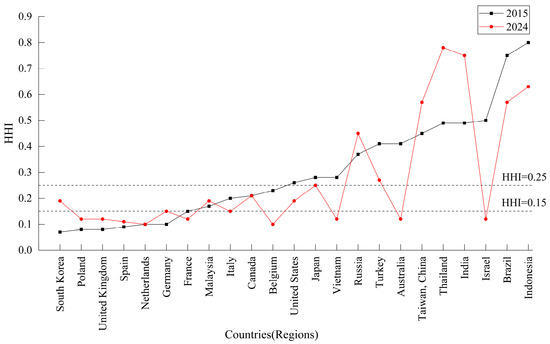

3.2. Resilience of China’s Bamboo Export Markets

Exports serve as the primary link connecting China’s bamboo industry with global markets, driving high-quality development and reflecting international competitiveness. From 2015 to 2024, exports consistently accounted for over 99% of China’s total bamboo trade value, underscoring their dominance. This section analyzes export market resilience—defined as the ability to maintain stability and growth amid external shocks, economic fluctuations, or policy changes [50]—which directly impacts the bamboo industry’s high-quality development and long-term competitiveness. Resilience is examined through two dimensions: (1) trade concentration (measured by HHI) to reveal demand characteristics; (2) demand preferences, analyzed via K-means clustering, to classify export markets by demand characteristics and capture preference heterogeneity. Integrating both dimensions, this progressive analysis comprehensively reveals the multidimensional resilience of China’s bamboo product export markets. Additionally, the top 23 export destinations (each >1% of total exports) represented 84.73% (2015) and 86.36% (2024) of China’s bamboo product exports, respectively, making them highly representative. In contrast, other countries (regions) contributed <1% each, with limited diversity, low stability, and significant data volatility that could distort analysis. Thus, this study focuses on these 23 key export markets to analyze their resilience and evolutionary trends from 2015 to 2024.

3.2.1. Analyzing Trade Concentration in Key Export Markets

Based on different HHI thresholds, China’s major bamboo product export markets were classified into three categories (Table 2 and Table 3), highlighting structural shifts in market concentration between 2015 and 2024 (Figure 8). Low Concentration Markets (HHI < 0.15) expanded from six countries in 2015 to nine in 2024, indicating balanced and diversified demand structures. Moderate Concentration Markets (0.15 ≤ HHI < 0.25) increased slightly from five to six countries, characterized by some diversity but with specific product categories partially dominant. High Concentration Markets (HHI ≥ 0.25) decreased notably from twelve to eight countries, reflecting highly concentrated demand focused on a few specific product categories. Significant changes in HHI were observed in certain countries: India and Thailand experienced considerable increases of 0.26 and 0.29, respectively, while Australia and Israel recorded substantial decreases of 0.29 and 0.38, respectively. Compared with 2015, the structural adjustment of market concentration in 2024 has led to an overall reduction in trade concentration and a notable improvement in export market resilience.

Table 2.

Trade Concentration in Key Export Countries (Regions) in 2015.

Table 3.

Trade Concentration in Key Export Countries (Regions) in 2024.

Figure 8.

Trade Concentration Comparison in Key Export Countries (Regions) in 2015 and 2024.

Combining export value with concentration analysis, it was found that high-concentration markets dominated China’s bamboo exports in 2015 (Table 2), with major economies such as the United States, Japan, China’s Taiwan and Australia together accounting for 51.22% of total exports, reflecting a “highly concentrated head market” structure. By 2024 (Table 3), market structure had significantly optimized, with the United States, The Netherlands, Germany, Vietnam, and France classified as moderate- to low-concentration markets, cumulatively accounting for 35.45% of exports, indicating stronger and more stable trade relationships.

Although diversification has improved and export market resilience has strengthened, certain key market, notably Thailand and India, still exhibit high concentration levels (HHI > 0.7) and strong reliance on single product categories, making them vulnerable to price volatility and supply chain disruptions. Therefore, China’s bamboo industry should consolidate stable partnerships with markets like the United States, The Netherlands, and Germany, while promoting diversified product exports to high-concentration markets such as Thailand and India to optimize global market distribution and enhance international competitiveness.

3.2.2. Identifying Demand Preferences in Key Export Markets

Export composition ratios were calculated to identify the demand preferences of key countries (Table A1 and Table A2). Taking the United States as an example, as shown in Table A2, among the seven categories of bamboo products it imported from China in 2024, Bamboo Tableware accounted for a high proportion of 49.14%, while Bamboo Food Products only accounted for 4.28%, highlighting a strong preference for Tableware. Across markets, Bamboo Tableware consistently dominated demand, while Bamboo Food Products and Bamboo Fiber Products rarely exceeded 10%, indicating weak international demand and significant market gaps, particularly in France, Poland, and Israel.

Following dimensionality reduction using Principal Component Analysis, the optimal number of clusters (K) was determined through the Elbow Method and Silhouette Method (Figure 9). The SSE curve exhibited distinct inflection points at K = 7 for 2015 and K = 5 for 2024, corresponding to peak silhouette coefficients of 0.50 and 0.49, respectively. These results indicated well-separated clusters and high internal homogeneity. Consequently, the 23 major export countries (regions) were optimally grouped into seven clusters in 2015 and five clusters in 2024 (Table A1 and Table A2).

Figure 9.

Determination of Optimal k Using Silhouette Coefficient (Left) and SSE (Right).

The 2015 market clustering results revealed a clear demand gradient across seven market categories, ranging from “diversified equilibrium” to “unipolar dominance”. Types I and II were classified as “markets with diversified demand”, albeit characterized by distinct patterns. Specifically, Type I included six markets, such as Germany and Korea, demonstrating low concentration with relatively uniform demand distributions across most bamboo product categories, except for notably lower demand in Bamboo Furniture and Bamboo Fiber Products. Type II, consisting of four markets including Malaysia and Belgium, showed slightly reduced diversification, featuring pronounced demand for Bamboo Tableware, Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials, and Bamboo Handicrafts. In contrast, Types III to VII were predominantly high-concentration markets, each dominated by specific bamboo product categories yet internally differentiated. Type III markets, represented by the United States and Australia, exhibited dominance in Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials, accounting for approximately 55% of imports. Type IV, comprising Vietnam and Japan, focused primarily on Bamboo Food Products. Meanwhile, Type V, including Israel and Italy, was characterized by a dominant demand for Bamboo Handicrafts. Finally, although both Types VI (India, Turkey) and VII (five markets including Thailand and Brazil) were dominated by Bamboo Tableware, markets in Type VI notably distinguished themselves by a significantly higher import share of Bamboo Fiber Products (exceeding 13%), whereas other markets in Type VII reported shares below 3%.

By 2024, the markets consolidated into five clusters, indicating a shift from “single-category dominance” to more “diversified demand” structures, alongside a significant rise in demand for Bamboo Tableware across all clusters. Types I to IV represented diversified markets, with Type I—including the United States, Germany, and ten other partners—characterized by balanced demand across multiple categories. Notably, Bamboo Furniture and Other Bamboo Products accounted for 10–20% of imports, underscoring broad-based demand. Type II markets (Malaysia, Israel) showed strong preference for Construction and Decoration Materials (37.38% and 33.05%), while Types III and IV favored Bamboo Food Products (Japan, Vietnam) and Bamboo Fiber Products (Turkey), respectively. Type V markets, including Thailand and India, remained highly concentrated, with Bamboo Tableware comprising an average of 77.55% of imports.

From 2015 to 2024, significant shifts in product demand structure were observed. The average import share of Bamboo Food Products, Construction and Decoration Materials, and Handicrafts contracted sharply, with Bamboo Food Products and Bamboo Fiber Products dropping to 4.97% and 2.51%, respectively, by 2024. Conversely, Bamboo Tableware’s share surged to 51.86%. These changes were driven by two main factors: (1) evolving market preferences, such as the rise in Bamboo Tableware demand in the United States (from 21.67% in 2015 to 49.14% in 2024) and the sharp decline in Australia’s demand for Construction Materials (from 67.87% to 7.77%); and (2) revisions to HS codes in 2017, which introduced finer product classifications, such as the addition of “44219190 Other bamboo products, not elsewhere specified”, thereby altering the statistical composition. Together, these dynamics reflect both deep shifts in global consumer trends and the critical role of refined trade classification systems in accurately capturing structural market changes.

4. Discussion

The “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative offers a nature-based, sustainable alternative to petroleum-based plastics: bamboo is fast-growing, maturing in 3–5 years, and renewable, enabling sustainable harvesting [51]; it boasts exceptional carbon sequestration capacity of 100–243 tonnes of ecosystem carbon storage per hectare [52], contributing to ecological balance [53]; it is highly versatile for full-material utilization with minimal waste, and the labor-intensive bamboo sector boosts employment and rural incomes—collectively positioning bamboo products as a viable solution to reduce global reliance on petroleum-based plastics and advance plastic pollution governance [54]. Yet, while previous studies have well-established spatiotemporal evolution and market resilience analysis for grain and timber trade [55,56], these areas remain insufficiently explored for bamboo product trade. Thus, this study comprehensively applies descriptive analysis, visualization processing, K-means clustering, and trade concentration indices to systematically examine dynamic changes in bamboo product HS codes, explore the alignment between import-export classifications and codes, analyze the spatiotemporal characteristics of trade volume, product composition, and market distribution, and investigate the export market resilience of China’s bamboo product trade, with subsequent discussions and recommendations presented below.

- Refine Bamboo Product Coding and Improve Statistical Systems

The current HS code 44219190, which corresponds to “Other bamboo products, not elsewhere specified,” accounts for 8.21% of China’s total bamboo export value, indicating that the current statistical framework for bamboo products is not yet comprehensive and fails to fully capture the diversity and sub-categories of bamboo products. The existing statistical framework is unable to fully cover the diversity and granularity of bamboo trade and cannot accurately track the evolving trade dynamics. This aligns with the viewpoint proposed by Cawthorn et al. (2017), which highlighted that “the lack of specific fish sub-coding leads to a decrease in the traceability of global trade data” [57], reflecting the mismatch between the rapid innovation of emerging industries and the updating cycle of institutional statistical systems. To address this issue, it is essential to establish a more detailed and adaptive classification system. This can be achieved by leveraging the existing “Key Promotion Catalogue of Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic Achievements” to add sub-categories for emerging bamboo products and “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” alternatives. This classification refinement will help improve the accuracy of trade data, more precisely track industry trends, and provide more accurate and actionable data to support policy decisions and business strategies.

- 2.

- Consolidate Traditional Markets and Expand Emerging Ones

Prioritize the consolidation of mature markets. The United States, Japan, and the EU, as major export destinations for China’s bamboo products, have evolved into mature markets through long-term stable trade interactions, playing a key role in stabilizing the export volume of China’s bamboo products. Efforts should be made to accurately align with the consumption preferences of these markets—such as the preference for Bamboo Tableware in the United States, Japan, and most EU countries—and formulate differentiated strategies based on each market’s consumption habits and access regulations to further consolidate the foundation of these mature markets. Prioritize expanding emerging markets in Southeast and South Asia. Meanwhile, trade concentration analysis indicates an overall decline, reflecting a marked improvement in the resilience and external risk resistance of China’s bamboo product export markets—consistent with Duan et al.’s research on the correlation between China’s grain export concentration and enhanced trade resilience [58]. For highly concentrated markets such as Thailand, India, and Indonesia, on the basis of stabilizing traditional exports, differentiated products should be developed to meet specific local demands and mitigate trade risks. Additionally, markets including France, Poland, and Israel have gaps in Bamboo Food Products and Bamboo Fiber Products with substantial development potential. Targeted marketing strategies tailored to local consumer needs and cultural preferences are recommended to further promote the diversification of China’s bamboo product export markets.

- 3.

- Technology-Driven Product Upgrades and Enhancing Core Competitiveness

China’s bamboo trade structure is characterized by decreasing imports and steadily growing exports. Bamboo Tableware accounts for 51.13% of exports and stands out as a high-value product category aligned with the global trend of reducing plastic. To enhance its competitiveness, efforts should focus on technological upgrades, such as increased investment in innovations like mold-resistant coatings, heat treatment processes, and intelligent thermoforming techniques [59], which can significantly improve product durability, functionality, and production efficiency. At the same time, establishing standardized product systems (e.g., uniform size tolerances, environmental indicators) and incorporating culturally resonant design elements can further enhance product value. Given the limited demand for Bamboo Fiber Products in key export markets, greater emphasis should be placed on the development of deep-processing technologies to overcome technical barriers such as composite strength and weather resistance.

- 4.

- Optimizing the Supply Chain for Primary Bamboo Products

China’s bamboo product imports remain dominated by primary products, characterized by fragmented categories and significant year-to-year fluctuations. Although cooperation with key suppliers such as China’s Taiwan, Vietnam, and Japan has improved coordination and partially reduced the uncertainty caused by fragmentation, the overall dispersed pattern still poses potential constraints on the continuity of downstream processing and the stability of product quality. At the same time, the efficiency of supply chain integration for primary products directly influences the international competitiveness of China’s processed bamboo goods. Therefore, optimizing the supply chain should focus on building long-term strategic partnerships with core sourcing regions to transition from fragmented procurement to a more centralized and standardized supply model, while also enhancing vertical integration between raw material supply and processing to improve overall supply chain efficiency.

- 5.

- Policy-Industry Synergy for SDG Alignment

With the global advancement of plastic bans and the deepening of the “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative, restrictions on plastic usage have significantly driven demand for sustainable materials, presenting a major opportunity for the bamboo industry. In this context, the bamboo industry needs to establish coordinated mechanisms between policymakers and enterprises. This includes revising HS codes to highlight the eco-friendly attributes of bamboo products, making it easier for them to receive green policy support in international trade; optimizing export incentives to encourage the use of low-carbon bamboo products and circular economy technologies, guiding enterprises towards green and sustainable development. Through this coordination, industrial development can be closely aligned with the SDGs, not only improving the global adaptability of the bamboo industry but also expanding the international impact of bamboo products and the “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” initiative through green product trade and technology cooperation.

5. Conclusions

This study applies descriptive statistical analysis, visualization, K-means clustering, and the HHI to examine the evolving competitiveness of China’s bamboo industry in international trade and assess the resilience of its export markets. The main conclusions are as follows: (1) The year 2017 marked a key turning point in the evolution of bamboo product classifications under China’s customs HS coding system. Four new codes were introduced, including the residual category 44219190 “Other bamboo products, not elsewhere specified”, and ten product codes or descriptions were revised. As of 2024, a total of 37 bamboo product categories are in use. (2) In China’s bamboo import-export trade, exports accounted for 99.73% of the total trade value in 2024, indicating an overwhelmingly dominant position and highlighting a significant trade surplus advantage. (3) The overall value of imports has declined, with product types being relatively dispersed and primarily consisting of raw or low-processed materials. Meanwhile, import sources have become more concentrated, with China’s Taiwan and Vietnam emerging as stable and critical suppliers. (4) While exports have generally shown an upward trend, there has been a decline in 2023 and 2024 compared to the peak in 2022. This suggests a need for further optimization of product structure and diversification of export markets to better mitigate risks stemming from global demand fluctuations and trade barriers. (5) The export portfolio remains highly concentrated, predominantly composed of processed goods, with Bamboo Tableware as the leading category. In 2024, Bamboo Tableware accounted for 51.13% of total export value, the highest share since 2015. The United States and Japan are China’s largest export markets. Export destinations have steadily expanded, and the number of trade partners has increased. This indicates steady improvement in the international competitiveness of China’s bamboo industry and reflects growing global recognition and demand for Chinese bamboo products. (6) Based on differences in trade concentration, China’s key export markets for bamboo products were divided into three categories. Between 2015 and 2024, low-concentration markets increased from six to nine, moderate-concentration markets rose from five to six, and high-concentration markets decreased from twelve to eight. This indicates a structural adjustment toward lower trade concentration and significantly enhanced resilience in China’s export markets. (7) Further clustering analysis identified changes in demand preferences across 23 key markets. In 2015 and 2024, the markets were classified into seven and five clusters, respectively, showing a trend of “increasing diversified demand markets and decreasing single-category dominated markets”. Different clusters exhibited distinct demand preferences. Overall, demand for categories such as Bamboo Tableware significantly increased, while the share of traditional categories like Bamboo Food Products and Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials declined. This structural shift was driven by both evolving market preferences and refined trade classifications, reflecting broader trends in global consumption patterns and industry segmentation.

This study, based on China’s Customs data from 2015 to 2024, analyzes the spatial-temporal evolution and market resilience of China’s bamboo product international trade at the macro level. However, several limitations remain that need to be addressed: the current research mainly focuses on macro trade data from Customs and lacks in-depth tracking of micro-level dynamics, such as production processes and technological iterations of specific bamboo products; furthermore, the analysis of bamboo resources, industry development, and policy status in trade partner countries is not yet comprehensive. Future research should conduct a deeper comparative analysis of the resource bases, industrial development, policy orientations, and market characteristics of key bamboo product trade partner countries, in order to clarify the division of labor and advantages within the global bamboo industry value chain and contribute to the high-quality development of the global bamboo industry and the sustainable economic and social development.

Author Contributions

Data curation, writing—original draft, Q.W.; Methodology, writing—review and editing, L.Z.; Formal analysis, P.L.; Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, E.X.; Supervision, Software, Conceptualization, W.Y. and X.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of ICBR (1632022003 & 1632025011).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset on China’s international trade in bamboo products analyzed in this study is publicly available from the official website of the General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China, accessible at: http://stats.customs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals; INBAR: International Bamboo and Rattan Organization; NDRC: National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China; NFGA: National Forestry and Grassland Administration of the People’s Republic of China; HS code: International Convention for Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System; HHI: Herfindahl-Hirschman Index; PCA: Principal Component Analysis; SSE: Sum of Squared Errors; CNY: Chinese Yuan.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2015. To systematically identify and classify the demand preferences of key export destinations for China’s bamboo products, K-means clustering was employed based on demand characteristics. The results were visualized through a heatmap, where color intensity reflected the degree of preference.

Table A1.

Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2015. To systematically identify and classify the demand preferences of key export destinations for China’s bamboo products, K-means clustering was employed based on demand characteristics. The results were visualized through a heatmap, where color intensity reflected the degree of preference.

| Trading Partners | Bamboo Food Products | Bamboo Tableware | Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials | Bamboo Weaving and Handicrafts | Bamboo Furniture | Bamboo Fiber Products | Other Bamboo Products | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 18.42% | 38.43% | 11.90% | 12.36% | 14.07% | 1.80% | 3.02% | 1 |

| South Korea | 22.33% | 24.58% | 10.13% | 25.29% | 9.36% | 0.95% | 7.36% | |

| United Kingdom | 16.24% | 32.83% | 12.45% | 22.57% | 7.38% | 0.16% | 8.38% | |

| Spain | 15.00% | 30.22% | 6.67% | 25.86% | 4.46% | 0.00% | 17.79% | |

| Netherlands | 11.25% | 33.76% | 23.75% | 10.10% | 3.32% | 0.00% | 17.83% | |

| Poland | 5.45% | 27.29% | 23.48% | 18.63% | 4.90% | 0.44% | 19.81% | |

| Malaysia | 1.74% | 33.16% | 26.19% | 32.26% | 4.96% | 0.00% | 1.69% | 2 |

| Belgium | 3.29% | 52.30% | 20.37% | 14.07% | 4.56% | 2.17% | 3.24% | |

| France | 6.52% | 37.45% | 14.35% | 31.33% | 7.00% | 0.00% | 3.34% | |

| Canada | 3.13% | 43.21% | 33.51% | 13.38% | 2.75% | 0.00% | 4.03% | |

| United States | 7.16% | 21.67% | 55.14% | 10.17% | 4.04% | 0.21% | 1.60% | 3 |

| Australia | 2.32% | 17.71% | 67.87% | 5.54% | 4.57% | 0.23% | 1.78% | |

| Vietnam | 46.84% | 38.94% | 1.96% | 12.18% | 0.02% | 0.00% | 0.07% | 4 |

| Japan | 51.43% | 32.65% | 1.62% | 9.90% | 0.50% | 0.06% | 3.84% | |

| Israel | 0.00% | 19.95% | 4.35% | 72.88% | 0.87% | 0.26% | 1.69% | 5 |

| Italy | 4.41% | 24.15% | 9.32% | 49.06% | 4.90% | 0.46% | 7.69% | |

| India | 0.48% | 73.58% | 4.37% | 5.17% | 1.84% | 13.89% | 0.67% | 6 |

| Turkey | 0.00% | 68.48% | 4.34% | 8.57% | 2.69% | 13.13% | 2.79% | |

| Thailand | 11.43% | 73.33% | 10.86% | 2.79% | 0.97% | 0.42% | 0.21% | 7 |

| Brazil | 0.14% | 88.22% | 2.37% | 8.47% | 0.58% | 0.00% | 0.23% | |

| Russia | 0.43% | 64.35% | 13.31% | 17.15% | 2.72% | 0.73% | 1.30% | |

| Indonesia | 0.77% | 90.79% | 2.90% | 2.68% | 0.20% | 0.27% | 2.39% | |

| Taiwan, China | 2.44% | 69.53% | 0.88% | 20.08% | 1.13% | 0.23% | 5.71% | |

| Means | 10.05% | 45.07% | 15.74% | 18.72% | 3.82% | 1.54% | 5.06% | - |

Table A2.

Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2024. The results were visualized through a heatmap, where color intensity reflected the degree of preference. This table forms a comparison with Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2015.

Table A2.

Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2024. The results were visualized through a heatmap, where color intensity reflected the degree of preference. This table forms a comparison with Cluster Analysis Results of Demand Preferences in Key Export Destinations in 2015.

| Trading Partners | Bamboo Food Products | Bamboo Tableware | Bamboo Construction and Decoration Materials | Bamboo Weaving and Handicrafts | Bamboo Furniture | Bamboo Fiber Products | Other Bamboo Products | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 4.28% | 49.14% | 8.07% | 7.52% | 16.31% | 0.09% | 14.60% | 1 |

| Netherlands | 3.62% | 35.77% | 13.91% | 12.31% | 10.21% | 0.75% | 23.43% | |

| Germany | 4.89% | 41.79% | 4.13% | 7.11% | 23.89% | 1.54% | 16.66% | |

| France | 1.84% | 39.05% | 10.27% | 15.30% | 15.25% | 0.00% | 18.28% | |

| United Kingdom | 6.58% | 40.50% | 4.34% | 12.75% | 15.17% | 1.55% | 19.11% | |

| South Korea | 13.35% | 48.95% | 3.86% | 5.77% | 6.51% | 0.94% | 20.61% | |

| Poland | 1.36% | 36.15% | 10.06% | 13.79% | 12.18% | 0.00% | 26.46% | |

| Italy | 3.31% | 44.28% | 7.85% | 20.16% | 9.20% | 2.88% | 12.32% | |

| Spain | 4.72% | 38.46% | 8.55% | 13.00% | 13.22% | 0.42% | 21.63% | |

| Australia | 5.33% | 38.95% | 7.77% | 11.09% | 21.91% | 0.03% | 14.93% | |

| Canada | 5.04% | 51.42% | 3.60% | 10.08% | 10.91% | 0.28% | 18.68% | |

| Belgium | 1.11% | 35.23% | 19.01% | 12.33% | 17.88% | 1.06% | 13.36% | |

| Malaysia | 2.25% | 38.83% | 37.38% | 4.16% | 8.10% | 0.87% | 8.40% | 2 |

| Israel | 0.01% | 23.95% | 33.05% | 23.76% | 8.07% | 0.01% | 11.15% | |

| Japan | 34.67% | 47.65% | 4.56% | 5.47% | 2.89% | 0.16% | 4.60% | 3 |

| Vietnam | 18.67% | 39.85% | 8.90% | 19.14% | 1.70% | 3.55% | 8.19% | |

| Turkey | 0.02% | 55.27% | 0.63% | 10.07% | 2.30% | 22.41% | 9.29% | 4 |

| Thailand | 0.49% | 89.80% | 2.00% | 0.46% | 6.54% | 0.11% | 0.61% | 5 |

| India | 0.23% | 88.09% | 1.44% | 0.81% | 0.30% | 7.37% | 1.76% | |

| Taiwan, China | 1.89% | 78.82% | 2.70% | 6.90% | 1.95% | 0.05% | 7.69% | |

| Indonesia | 0.27% | 81.59% | 1.41% | 1.33% | 2.74% | 10.73% | 1.93% | |

| Brazil | 0.00% | 78.50% | 2.98% | 9.40% | 2.36% | 0.83% | 5.92% | |

| Russia | 0.41% | 70.80% | 1.79% | 7.31% | 5.08% | 2.10% | 12.51% | |

| Means | 4.97% | 51.86% | 8.62% | 10.00% | 9.33% | 2.51% | 12.70% | - |

References

- Gan, J.; Chen, M.; Semple, K.; Liu, X.; Dai, C.; Tu, Q. Life cycle assessment of bamboo products: Review and harmonization. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 849, 157937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, S.; Chiu, M. Bamboo sector reforms and the local economy of Linan County, Zhejiang Province, People’s Republic of China. For. Policy Econ. 2000, 1, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Baredar, P.; Prakash, O. Bamboo as a complementary crop to address climate change and livelihoods—Insights from India. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 102, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tan, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Y. Bamboo Forests: Unleashing the Potential for Carbon Abatement and Local Income Improvements. Forests 2024, 15, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INBAR. Bamboo, Rattan and the SDGs: How Countries Can Harness These Resources to Add Value to Action Plans for Sustainable Development [Position Paper]. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/forests/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/INBAR_input_AHEG2016.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Council of the EU. Statement of the Council’s Reasons: Position (EU) No 3/2015 of the Council at First Reading with a View to the Adoption of a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 94/62/EC as Regards Reducing the Consumption of Lightweight Plastic Carrier Bags (2015/C 101/02). Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, C101, 6. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=oj:JOC_2015_101_R_0002 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Huang, F.; Cai, Z.; Lin, S. Charting the research status for bamboo resources and bamboo as a sustainable plastic alternative: A bibliometric review. Forests 2024, 15, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, D. Current situation and countermeasures of bamboo industry development in China. Chin. Rural Econ. 2004, 2004, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Kobayashi, M. Plantation future of bamboo in China. J. For. Res. 2004, 15, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Wei, J. From “whole bamboo utilization” to “full bamboo application”. Minbei Daily 2024., 001. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, A. Potential of Bamboo in Sustainable Development. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2008, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, B.; Ihsan, M.; Permana, M.D.; Noviyanti, A.R. A Review of Bamboo: Characteristics, Components, and Its Applications. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2522928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INBAR. Trade Overview 2022: Bamboo and Rattan Commodities in the International Market; INBAR: Beijing, China, 2023; Available online: https://www.inbar.int/resources/inbar_publications/2022qqztspgjmybg/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Huang, L.; Fang, T.; Zhou, M. Study on trade of bamboo and rattan products of China, Japan and Korea. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, Hangzhou, China, 4–6 December 2010; pp. 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Cheng, B.; Ma, H. Analysis of global bamboo product trade network characteristics. For. Resour. Manag. 2021, 2021, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Jiang, Q. Global live bamboo trade patterns and China’s influence. J. Ningxia Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 42, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Chen, K.; Zhou, M.; Nuse, B. Gravity models of China’s bamboo and rattan products exports: Applications to trade potential analysis. For. Prod. J. 2019, 69, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Xiao, J. Research on trade flow and potential of China’s bamboo and rattan products—Based on gravity model test. For. Prod. Ind. 2022, 61, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Status and trends of world bamboo and rattan commodity trade. World For. Res. 2009, 22, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, H.; He, L.; Pan, C.; He, M. Research and development trends of bamboo-based materials in the construction sector replacing plastic. J. For. Eng. 2024, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Yrjälä, K.; Vinod, K.K.; Sharma, A.; Cho, J.; Satheesh, V.; Zhou, M. Genetics and genomics of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis): Current status, future challenges, and biotechnological opportunities. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Fan, B. Analysis on the current situation and policies of China’s bamboo industry development. J. Beijing For. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2005, 2005, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Sun, H. Bamboo breeding strategies in the context of “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic Initiative”. Forests 2024, 15, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council Leading Group Office of the Third National Land Survey; Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China; National Bureau of Statistics. Main Data Bulletin of the Third National Land Survey; The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-08/26/content_5633490.htm (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Latiff, A.R.A. Development of the bamboo forest economy: Reviewing China’s ‘bamboo as a substitute for plastic initiative’. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2025, 11, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NFGA. China Forestry and Grassland Statistical Yearbook 2020; NFGA: Nashua, NH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Yu, W. Global bamboo resource status and trends. China’s Wild Plant Resour. 2024, 43, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- State Forestry Administration of China. China Forestry Statistical Yearbook 2008; State Forestry Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2009; Available online: http://202.106.125.35/CSYDKNS/Navi/YearBook.aspx?id=N2010080090&floor=1 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- NFGA. China Forestry and Grassland Statistical Yearbook 2022; NFGA: Nashua, NH, USA, 2023; Available online: http://202.99.63.178/u/cms/www/202401/30112405slws.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Erkan, B.; Bozduman, E.T. Analysis of export concentrations of China and Japan on product basis. ASSAM Int. Ref. J. 2021, 8, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.; Chang, E. Industrial concentration in South Korea: Implications for the auction design of carbon contracts for difference scheme. Clim. Policy 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleckis, K. Determining the Level of Market Concentration in the Construction Sector—Case of Application of the HHI Index. Sustainability 2022, 14, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Export Diversification. Statistics Canada Daily, 11 December 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/171211/dq171211b-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Chen, C.; Peng, H. Community characteristics and classification of the Taibai red cedar forest in Qinling. For. Sci. 1994, 1994, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, B. Market competition analysis of travel agency line products based on cluster analysis—Taking Sichuan province as an example. Tour. J. 2006, 2006, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Papamichail, G.P.; Papamichail, D.P. The k-means range algorithm for personalized data clustering in e-commerce. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlamova, G.; Vertelieva, O. The international competitiveness of countries: Economic-mathematical approach. Econ. Sociol. 2013, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.Y.; Cho, S.I. Treatment variation related to comorbidity and complications in type 2 diabetes: A real world analysis. Med. 2018, 97, e12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Garcia, M.; Ibar-Alonso, R.; Arenas-Parra, M. A comprehensive framework for explainable cluster analysis. Inf. Sci. 2024, 663, 120282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Customs of China. China Bamboo Product Import and Export Data 2015–2025. 2025. Available online: http://.stats.customs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Scope and Classification of Import and Export Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/zs/tjws/zytjzbqs/zckze/202411/t20241115_1957489.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- NFGA. “Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic” Key Technology Achievements Released. 2025. Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/lcdt/636137.jhtml (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Mchumo, A.; Wang, R. Bamboo: A potential tool for climate change mitigation and adaptation. In Global Development and Cooperation with China; Wang, H.H., Miao, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. EU plastic restriction policy: Connotation, characteristics and implications. Int. Forum 2016, 18, 66–71+79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Elomri, A.; Kerbache, L.; El Omri, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on global supply chains: Facts and perspectives. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Pan, T. Analysis of the current situation, trend forecast and policy recommendations of China’s foreign trade under the background of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Trade 2021, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDRC; Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China; NFGA. Three-Year Action Plan to Accelerate the Development of Bamboo as a Substitute for Plastic. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202311/P020231102681566560384.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P.; Tyler, P. Local growth evolutions: Recession, resilience and recovery. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2015, 8, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Tan, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhong, L.; Yu, L. Mapping large-scale bamboo forest based on phenology and morphology features. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Meng, C.; Jiang, P.; Xu, Q. Review of carbon fixation in bamboo forests in China. Bot. Rev. 2011, 77, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Wu, W.; Ji, W.; Zhou, M.; Xu, L.; Zhu, W. Evaluating the performance of bamboo forests managed for carbon sequestration and other co-benefits in Suichang and Anji, China. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 106, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ye, H.; Chen, F.; Wang, G. Bamboo as a substitute for plastic: Application performance and influencing mechanism of bamboo buttons. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Yu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and trade structure security assessment of China’s grain trade from 1987 to 2016. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 838–848. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhang, M. Static resilience evolution of the global wood forest products trade network: A complex directed weighted network analysis. Forests 2024, 15, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, D.M.; Mariani, S. Global trade statistics lack granularity to inform traceability and management of diverse and high-value fishes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, H. Trade vulnerability assessment in grain-importing countries: A case study of China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0316587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Lü, S.; Fu, F.; Huang, J.; Wang, S. Review of application of microencapsulation in wood functional materials and future trends. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2016, 52, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).