Effects of Separation Geotextiles in Unpaved Forest Roads on Control Measurements Using the Light Weight Deflectometer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Preliminary Checks

2.3. Permutation-Based ANOVA

2.4. Effect Size Estimation (Cohen’s D)

2.5. Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMMs)

3. Results

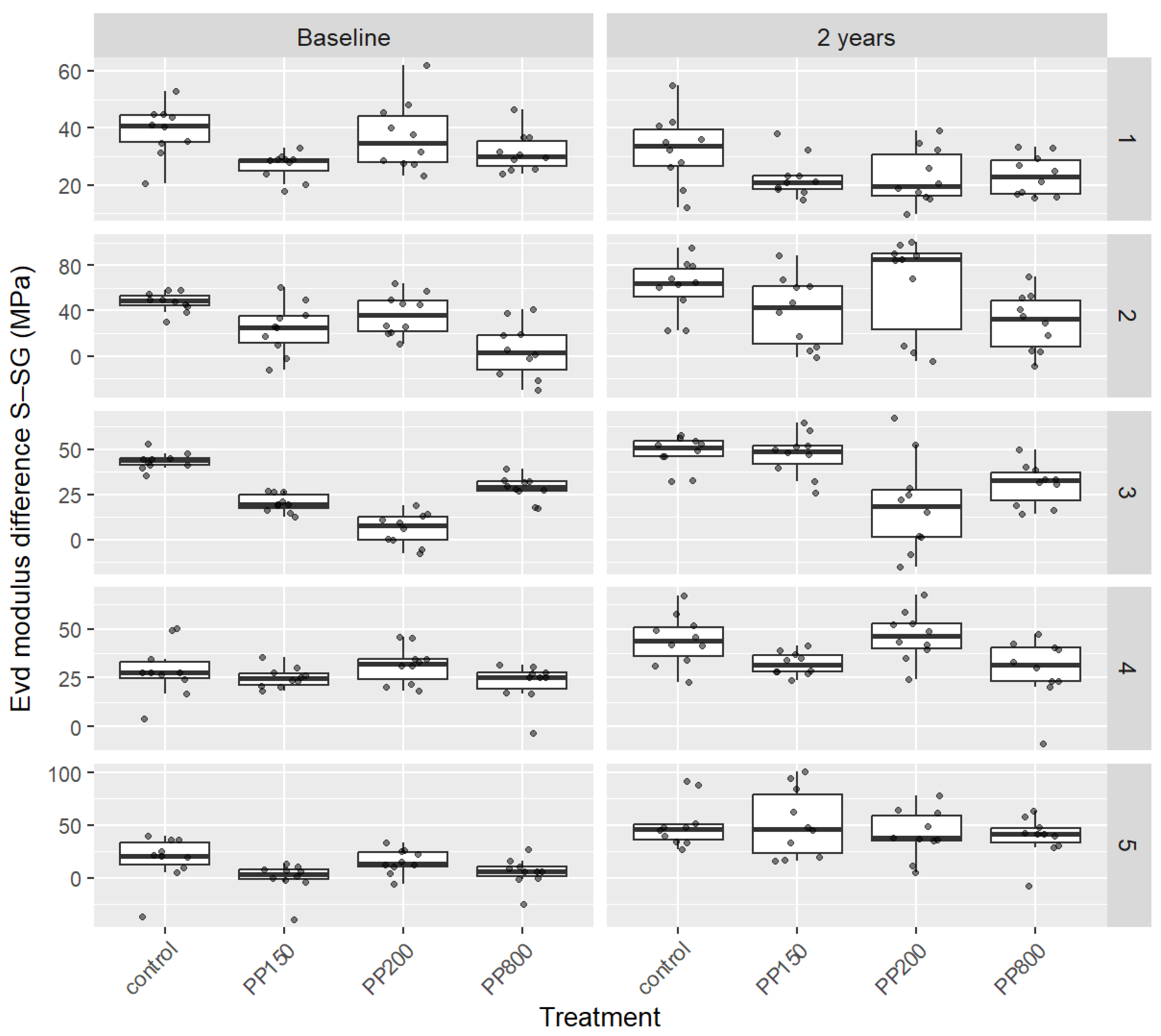

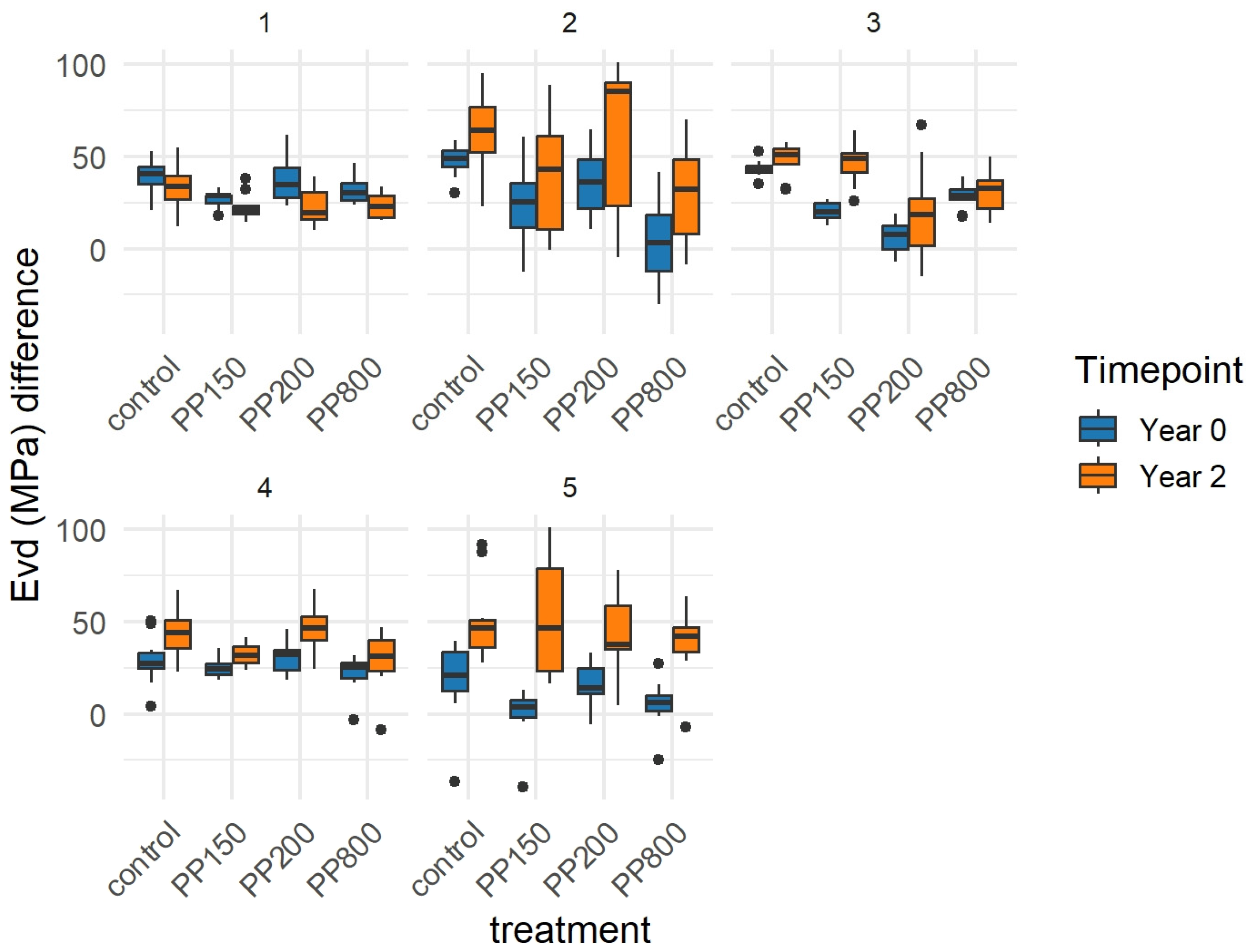

3.1. Initial Findings

3.2. Cohen’s D

3.3. Linear Mixed Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LWD | Light Weight Deflectometer |

| PLT | Plate Load Testing |

| DCPT | Dynamic cone penetration test |

References

- Martins, C.; Macedo, J.; Pinho-Lopes, M. Geocells for Unpaved Roads: Analysis of Design Methods from the Literature. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2024, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowicz, K.; Szymanek, S.; Kowalski, J.; Lendo-Siwicka, M. Stabilization of Loose Soils as Part of Sustainable Development of Road Infrastructure. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräu, G.; Vogt, S. Field and Laboratory Tests on the Bearing Behaviour of Unpaved Roads Reinforced by Different Geosynthetics. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zadehmohamad, M.; Luo, N.; Abu-Farsakh, M.; Voyiadjis, G. Evaluating Long-Term Benefits of Geosynthetics in Flexible Pavements Built over Weak Subgrades by Finite Element and Mechanistic-Empirical Analyses. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoueiry, N.; Briançon, L.; Riot, M.; Daouadji, A. Full-Scale Laboratory Tests of Geosynthetic Reinforced Unpaved Roads on a Soft Subgrade. Geosynth. Int. 2021, 28, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, E.M.; Araújo, G.L.S.; Santos, E.C.G. Sustainable Solutions with Geosynthetics and Alternative Construction Materials—A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, T.I.; Choudhary, A.K.; Choudhary, A.K. Performance Evaluation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates with Geosynthetics as an Alternative Subbase Course Material in Pavement Construction. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2685–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, P.; Shamrock, J.; Kawalec, J.; Touze, N. Sustainable Use of Geosynthetics in Dykes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, J.P.; Han, J.; Tutumluer, E.; Dobie, M.J.D. The Use of Geosynthetics in Roads. Geosynth. Int. 2023, 30, 47–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, B. Stiffness and Strength Improvement of Geosynthetic-Reinforced Pavement Foundation Using Large-Scale Wheel Test. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.A.; Kelly, M.A. Geotextile ‘Reinforced’ Unpaved Logging Roads: The Effect of Anchorage. Geotext. Geomembr. 1986, 4, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuelho, E.V.; Perkins, S.W. Geosynthetic Subgrade Stabilization—Field Testing and Design Method Calibration. Transp. Geotech. 2017, 10, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, G.; Berry, J. The Long History of Geosynthetics Use on Forest Roads. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2015, 2473, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornberg, J.G.; Roodi, G.H. Use of Geosynthetics to Mitigate Problems Associated with Expansive Clay Subgrades. Geosynth. Int. 2020, 28, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Bera, A.K. Development of Design Chart for Jute Geotextiles Reinforced Low Volume Road Section by Finite Element Analysis. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 2021, 8, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranko, E. Problem of selection of suitable geosynthetics for the strengthening of subgrade in road construction, selection of assessment criteria. Acta Sci. Pol. Architectura 2021, 20, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Alimohammadi, H.; Zheng, J.; Schaefer, V.R. Effectiveness of Geosynthetics in the Construction of Roadways: A Full-Scale Field Studies Review. In Proceedings of the IFCEE 2021, Dallas, TX, USA, 10–14 May 2021; pp. 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelch, W.W.; Rodgers, M.B.; Rawlinson, T.A.; McVay, M.C.; Herrera, R.A.; Horhota, D.J. Mechanically Stabilized Earth Pressures against Unyielding Surfaces Using Inextensible Reinforcement. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliburton, T.A.; Lawmaster, J.D.; McGuffey, V.C. Use of Engineering Fabrics in Transportation-Related Applications; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, G.; Ksaibati, K. Evaluation of Geogrid-Reinforced Granular Base. Geotech. Fabr. Rep. 2000, 18, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B.; Mohney, J. Durability of Geotextiles Used in Reinforcement of Walls and Road Subgrade. Transp. Res. Rec. 1994, 1439, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P.R.; Frost, M.W.; Lambert, J.P. Review of Lightweight Deflectometer for Routine In Situ Assessment of Pavement Material Stiffness. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2004, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttah, D. Determining the Resilient Modulus of Sandy Subgrade Using Cyclic Light Weight Deflectometer Test. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 27, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FGSV. ZTV E-StB 17: Zusätzliche Technische Vertragsbedingungen Und Richtlinien Für Erdarbeiten Im Straßenbau; FGSV: Cologne, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BASt. TP BF-StB Part B 8.3: Technische Prüfvorschriften Für Boden Und Fels Im Straßenbau—Dynamischer Plattendruckversuch; Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen: Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FSV. RVS 08.03.01 Erdarbeiten; Forschungsgesellschaft Straße—Schiene—Verkehr (FSV): Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Český Normalizační Institut. ČSN 73 6192: Rázové Zatěžovací Zkoušky Vozovek a Podloží; Český Normalizační Institut: Praha, Česká republika, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- IBDiM. Badanie i Ustalenie Zależności Korelacyjnych Dla Oceny Stanu Zagęszczenia i Nośności Gruntów Niespoistych Płytą Dynamiczną; Instytut Badawczy Dróg i Mostów: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Slovenský Ústav Technickej Normalizácie, Metrológie a Skúšobníctva. STN 73 6192:2011—Ľahký Dynamický Doskový Skúšobný Test Vrstiev Stavebných Konštrukcií; Slovenský Ústav Technickej Normalizácie, Metrológie a Skúšobníctva: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM International. ASTM E2835-21: Standard Test Method for Measuring Deflections Using a Portable Impulse Plate Load Test Device; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Cho, J.W.; Lee, S.Y. Field Evaluation and Application of Intelligent Quality Control Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiziene, R.; Vaitkus, A.; Zofka, A.; Simanaviciene, R. An Alternative Method for Determination of Compaction Level for the Pavement Granular Layers. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2023, 24, 3029–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakarami, M.I.; Moghaddam, H.K. Evaluating the Performance of Rehabilitated Roadway Base with Geogrid Reinforcement in the Presence of Soil-Geogrid-Interaction. J. Rehabil. Civ. Eng. 2017, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Chen, W.; Nie, Y.; Ma, L. Evaluation of Required Stiffness and Strength of Cellular Geosynthetics. Geosynth. Int. 2022, 29, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Tutumluer, E.; Kim, M. Development of a Mechanistic Model for Geosynthetic-Reinforced Flexible Pavements. Geosynth. Int. 2005, 12, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, S.; Deb, P. Finite Element Analysis of Geogrid-Incorporated Flexible Pavement with Soft Subgrade. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Alkawaaz, N.G.; Al-Badran, Y.M.; Muttashar, Y.H. Evaluation of Geogrid-Reinforced Flexible Pavement System Based on Soft Subgrade Soils Under Cyclic Loading. Civ. Environ. Res. 2017, 9, 55–68. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/CER/article/view/40284/41432 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Kumar, V.V.; Saride, S.; Zornberg, J.G. Mechanical Response of Full-Scale Geosynthetic-Reinforced Asphalt Overlays Subjected to Repeated Loads. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 30, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstvo Zemědělství. Zpráva o Stavu Lesa a Lesního Hospodářství 2021. eAgri.cz; 2022. Available online: https://mze.gov.cz/public/portal/mze/publikace/zpravy-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho/zprava-o-stavu-lesa-a-lesniho-2021 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Český Statistický Úřad. Dopravní Infrastruktura–Časové Řady (doicr080123_2.xlsx). 2023. Available online: https://csu.gov.cz/docs/107508/2264c51a-40fe-369d-cff7-a7e92bfb890b/doicr080123_2.xlsx?version=1.0 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Faiz, A. The Promise of Rural Roads: Review of the Role of Low-Volume Roads in Rural Connectivity, Poverty Reduction, Crisis Management, and Livability. Transp. Res. Circ. No. E-C167; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; 52p, Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec167.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Český Normalizační Institut. ČSN 72 1006: Kontrola Zhutnění Zemin a Sypanin; Český Normalizační Institut: Praha, Česká republika, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grigolato, S.; Trzcí, G. Bearing Capacity of Forest Roads on Poor-Bearing Road Subgrades Following Six Years of Use. Forests 2022, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, M.; Hanandeh, S.; Mohammad, L.; Chen, Q. Performance of Geosynthetic Reinforced/Stabilized Paved Roads Built over Soft Soil under Cyclic Plate Loads. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptoo, D.K. An Investigation of the Effect of Dynamic and Static Loading to Geosynthetic Reinforced Pavements Overlying a Soft Subgrade; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.V.; Roodi, G.H.; Subramanian, S.; Zornberg, J.G. Influence of Asphalt Thickness on Performance of Geosynthetic-Reinforced Asphalt: Full-Scale Field Study. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, H.; Schaefer, V.R.; Zheng, J.; Li, H. Performance Evaluation of Geosynthetic Reinforced Flexible Pavement: A Review of Full-Scale Field Studies. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Lima, H.; Gonçalves, M. A Numerical Study on the Implications of Subgrade Reinforcement with Geosynthetics in Pavement Design. Procedia Eng. 2016, 143, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Trivedi, A.; Shukla, S.K. Strength Enhancement of the Subgrade Soil of Unpaved Road with Geosynthetic Reinforcement Layers. Transp. Geotech. 2019, 19, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, I.; Rootzén, J.; Johnsson, F. Reaching Net-Zero Carbon Emissions in Construction Supply Chains—Analysis of a Swedish Road Construction Project. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornberg, J.G.; Subramanian, S.; Roodi, G.H.; Yalcin, Y.; Kumar, V.V. Sustainability Benefits of Adopting Geosynthetics in Roadway Design. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2024, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniak, A.; Grajewski, S.M.; Kurowska, E.E. Bearing Capacity Standards for Forest Roads Constructed Using Various Technologies from Mechanically and Chemically Stabilised Aggregate. Croat. J. For. Eng. 2021, 42, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Road | Subgrade Soil Type | Length | Subgrade Treatment | Sub-Base Material | Sub-Base Height | Base-Coarse Material | Base-Coarse Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | (m) | - | - | (mm) | - | (mm) |

| #1 | undeveloped soil on weathered phyllite | 2695 | compaction | gravel aggregate 32/63 fraction | 200 | gravel aggregate 0/32 fraction | 100 |

| #2 | haplic podzols on weathered phyllite | 3355 | compaction | gravel aggregate 0/63 fraction | 200 | vibrated gravel | 100 |

| #3 | stagnic luvisols on weathered breccia | 1334 | lime stabilisation (400 mm depth) | gravel aggregate 0/63 fraction | 200 | vibrated gravel | 200 |

| #4 | haplic luvisols on weathered phyllite | 1556 | compaction | gravel aggregate 32/63 fraction | 200 | gravel aggregate 0/32 fraction | 100 |

| #5 | haplic podzols on weathered phyllite | 2509 | compaction | gravel aggregate 32/63 fraction | 200 | gravel aggregate 0/63 fraction | 100 |

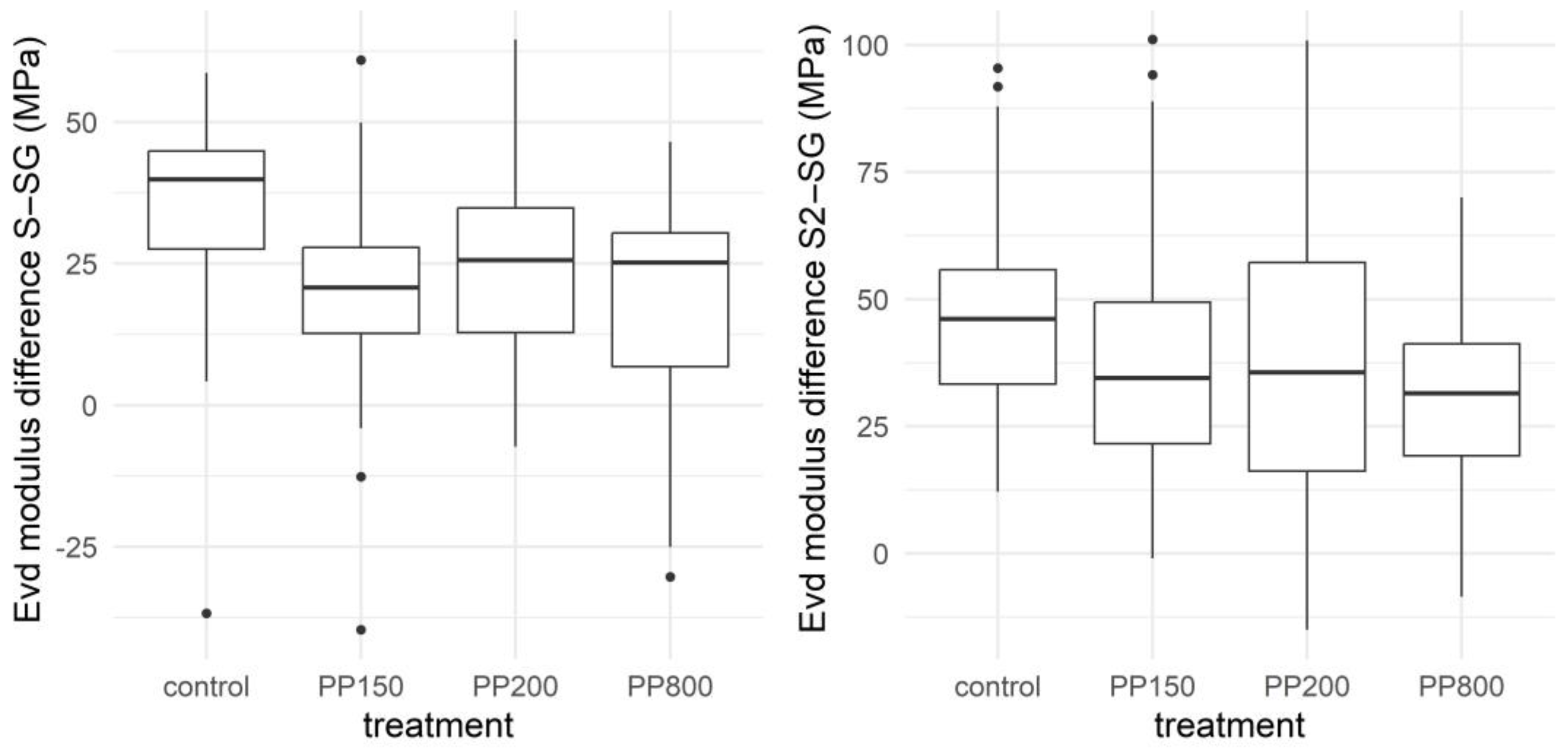

| Treatment | Mean S–SG | SD S–SG | Mean S2–SG | SD S2–SG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | ||||

| control | 35.4 | 16.6 | 47.3 | 18.8 |

| PP150 | 19.3 | 15.7 | 38.8 | 22.7 |

| PP200 | 25.5 | 17.3 | 38.5 | 29.2 |

| PP800 | 18.6 | 17.4 | 30.4 | 17.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ježek, J.; Nuhlíček, O.; Mráz, V.; Zlatuška, K. Effects of Separation Geotextiles in Unpaved Forest Roads on Control Measurements Using the Light Weight Deflectometer. Forests 2025, 16, 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111650

Ježek J, Nuhlíček O, Mráz V, Zlatuška K. Effects of Separation Geotextiles in Unpaved Forest Roads on Control Measurements Using the Light Weight Deflectometer. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111650

Chicago/Turabian StyleJežek, Jiří, Ondřej Nuhlíček, Václav Mráz, and Karel Zlatuška. 2025. "Effects of Separation Geotextiles in Unpaved Forest Roads on Control Measurements Using the Light Weight Deflectometer" Forests 16, no. 11: 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111650

APA StyleJežek, J., Nuhlíček, O., Mráz, V., & Zlatuška, K. (2025). Effects of Separation Geotextiles in Unpaved Forest Roads on Control Measurements Using the Light Weight Deflectometer. Forests, 16(11), 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111650