1. Forest-Based Bioeconomy and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

At the end of the twentieth century, growing awareness of pressure on natural resources led to a debate on the depletion of non-renewable inputs (mainly those related to fossil resources) and its consequences [

1]. Among other factors, the crucial importance of the substitutability of exhaustible resources with renewable ones is highlighted. This substitution would be possible thanks to a technological change that would allow the use of renewable resources at a lower cost than exhaustible ones [

2]. The bioeconomy has been positioned as one of the alternatives to mainstream economics in which renewable resources become “the path towards a more innovative, efficient in the use of resources and competitive society that reconciles food security with the sustainable use of renewable resources for industrial purposes, while guaranteeing the protection of the environment” [

3]. It is based on three fundamental factors: the biotechnological advanced knowledge of genes and complex cell processes, renewable biomass, and the integration of biotechnology applications across sectors [

4].

In this framework, forests and forest sector are important components of a bioeconomy [

5] and one of the pillars of the European bioeconomy [

6]. The forest sector contributes though traditional wood products, non-wood forest products (NWFP), emerging wood-based substitutes, biomass, and ecosystem services [

5]. Furthermore, the cascading use of forest products, mainly but not only in wood products, aims to increase the efficiency of biomass utilization by reusing, recycling and ultimately generating energy [

7]. We adopt a forest-based bioeconomy lens focused on entrepreneurial ecosystems as regional contexts where institutions, capabilities, and market uptake interact along the forest value chain. This complements prior work on European forest-based bioeconomy (FBB) measurement by applying an ecosystem-of-entrepreneurship focus to a Southern European region.

The FBB brings both opportunities and challenges for Europe’s forests: they represent the continent’s largest renewable source of energy and materials, yet they also deliver a wide spectrum of additional ecosystem services—from protective functions like soil erosion control to cultural benefits such as recreation—and provide valuable goods like game and mushrooms. It serves not only as a pathway to economic growth but also as a driver of sustainable development and a catalyst for action against climate change. In Europe, the development of FBB has increased in the last few years [

8], and several methodologies to measure this development have been proposed [

9,

10,

11]. To assess the development of the FBB in European regions, Barañano et al. [

12] propose an analytical framework based on the evaluation of ten key drivers, grouped into four categories: institutional, supply, demand, and biomass-related drivers. This framework combines both primary sources (expert interviews) and secondary sources (literature review), following a structured methodology that allows for comparative analysis across regions. The institutional dimension includes government plans and policies, R&D and innovation capacity, training and talent, entrepreneurship ecosystem, green public procurement, and participation in regional networks. The supply dimension addresses entrepreneurial capacities and the presence of clusters, while the demand dimension focuses on market awareness and consumer demand. Finally, the biomass-related driver assesses the availability and sustainability of forest biomass resources [

12].

Innovation plays an important role in the development of new products for a FBB, enabling entrepreneurs to creatively extract value from forest biomaterials [

13]. Entrepreneurship is identified as a main enabler of the transformation toward an innovative, knowledge-based, and sustainable bioeconomy [

13]. In the context of bioeconomy, entrepreneurs are seen as crucial for the transition toward a sustainable bioeconomy, turning environmental degradation caused by economic development into entrepreneurial opportunities [

14]. Entrepreneurial activity involves risk, especially when competing with established markets based on fossil resources. Managing this risk often involves “entrepreneurial experimentation”, rapidly testing new technologies and developing products, learning quickly from market exposure, and involving consumers early on. Developing innovative business models is a major task of entrepreneurs in the bioeconomy, aiming to change existing models not just by substituting resources but by introducing completely new ways of arranging value creation, potentially organized into different value chains or adopting whole-systems approaches [

15].

However, innovation and entrepreneurship do not occur in isolation. They are shaped by specific environments known as entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs)—regional contexts formed by interdependent actors, resources, and institutions that interact to support new venture creation. These ecosystems integrate formal and informal networks, physical infrastructure, and shared cultural outlooks, which collectively influence entrepreneurial capacity and innovation outcomes. EEs provide the systemic conditions (e.g., leadership, talent, finance, knowledge flows, and support services) necessary for productive entrepreneurship to emerge and scale [

16,

17]. In the bioeconomy, this means that the success of entrepreneurial efforts depends not only on individual initiative but on the structure and strength of the ecosystem that surrounds them. On the other hand, several market failures and related barriers affect bioeconomy development, including information asymmetries and uncertainty, externalities and spillovers, financing constraints, and regulatory/institutional obstacles, often compounded by network externalities due to geographic localisation [

18].

Despite not having a shared definition for the concept of EEs [

18], this generally refers to the interplay of multiple contextual factors—such as social, political, economic, and cultural conditions—that shape the capacity of a given territory to support entrepreneurship [

16]. Building on this understanding, we adopt a perspective that sees EEs as regional environments in which diverse actors, resources, and institutions interact to foster the creation and growth of innovative ventures. This includes both formal and informal networks among actors, the availability of physical infrastructure, and the presence of an entrepreneurial culture [

19,

20]. As Kuckertz et al. [

13] highlight, individual entrepreneurial activity is not sufficient for bioeconomy transformation: the environment in which entrepreneurial activities happen (regions in this case) and dynamic combinations of actors that collectively drive bioeconomic innovation, determine what kind of entrepreneurial activities are available and can be realized.

The bioeconomy offers a plethora of entrepreneurial opportunities [

21,

22,

23] and entrepreneurs are tasked with creatively extracting value from biomaterials [

14,

24,

25]. This is seen not only in research and technology-driven startups but also through initiatives like ecotourism or traditional products that can support the economic development of rural and indigenous communities [

26]. Nevertheless, while offering these opportunities, bioeconomy development is affected by several barriers and market failures as prices competitivity, lack of financial resources, lack of public or consumer awareness (asymmetric information failure), low commercialization and knowledge concerning technology and valorisation pathways, over-regulation or inadequate regulation and network externalities due to geographic localization [

18,

27].

In spite of the growing interest in the FBB, much of the existing research has focused on Northern and Central European contexts [

28], where institutional conditions, innovation systems, and entrepreneurial dynamics are relatively advanced. In contrast, Southern European regions such as the Spanish region of Castilla-La Mancha (CLM) remain underexplored in terms of their potential to foster forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystems (FBEE). Moreover, while analytical frameworks such as that of Barañano et al. [

12] provide valuable tools for assessing ecosystem drivers, there is a need to adapt and apply these frameworks to diverse territorial settings to better understand region-specific enabling and constraining factors. This study aims to contribute to this gap by providing an empirical assessment of the FBEE in CLM. In doing so, the research seeks to lay the foundations for advancing FBEEs in Southern European and other underexplored contexts.

In this context, the FBB and EEs are not isolated concepts but interdependent forces that, when aligned, can enable sustainable regional development. The FBB provides a resource base rich in environmental and productive potential, while entrepreneurial ecosystems offer the institutional and relational conditions necessary for innovation to flourish. When embedded within supportive ecosystems, forest-based bioeconomic initiatives can transition from isolated experiments to systemic change. However, the degree to which these ecosystems exist, are coordinated, and effectively mobilize actors around forest-based opportunities remains unclear—particularly in rural and structurally disadvantaged regions. This intersection forms the basis of this research, which explores how entrepreneurial ecosystems can be fostered in support of a regional forest-based bioeconomy, using the case of CLM as an empirical lens.

In this research, we are focused on the CLM, a region in Southern Europe where the 48% of the territory is classified as forest area (3,807,561 ha), being the second largest region of Spain in terms of forest surface [

29]. In recent years, the region has witnessed an increasing interest in linking forest resources with innovation and entrepreneurship, particularly in response to structural challenges such as rural depopulation (particularly in terms of young adults, from 25 to 39 years old [

30]), low industrial diversification, and underutilization of natural assets. These challenges are compounded by Spain’s documented rise in interregional, education-selective mobility among young adults and the growing internal brain drain from peripheral/rural areas toward major hubs, with skilled human capital accumulating in Madrid (1992–2018) [

30]. Framed within entrepreneurial-ecosystem terms, such outflows can trigger a capability trap—where weak returns and thin organizational routines further erode skills and innovation capacity, reinforcing low ecosystem performance over time [

31].

One of the actions carried out has been the creation of the Urban Forest Innovation Lab Cuenca (UFIL Cuenca) (an entrepreneurship and innovation training and incubation centre focused on forest resources) led by a consortium that includes the regional government of Castilla–La Mancha (Junta de Comunidades de Castilla–La Mancha, JCCM). These dynamics make CLM a particularly relevant context to explore the enabling and constraining factors for the emergence of forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystems in rural territories. In neighboring regions, orchestrating intermediaries already exist—CESEFOR in Castile and León and the Wood Cluster of Galicia (Cluster da Madeira de Galicia)—providing both a comparative benchmark and, in UFIL’s case, an aspirational model. This comparative perspective also motivates our purposive inclusion of CESEFOR in the sample (see

Section 2).

Building on the analytical framework of Barañano et al. [

12], the research objectives of this study are: (i) To identify the enabling and constraining factors that shape the development of forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystems in CLM; (ii) To examine the extent to which regional strategies and conditions align to foster innovation and entrepreneurship towards a forest-based bioeconomy; (iii) To analyse how specific regional initiatives contribute to innovation dynamics and the consolidation of entrepreneurial capacity within the FBEE.

2. Methodology

This research is a qualitative study focused on the conditions for the development of a FBEE in CLM with the aim of identifying the enabling factors and barriers for innovation, entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystem consolidation in the forestry sector of CLM.

To address the current research questions and objectives, this study adopts a qualitative case study approach focused on CLM, with particular attention to the role of UFIL Cuenca within the emerging forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem. The analysis applies the analytical framework of Barañano et al. [

12], which evaluates ten key drivers of forest-based bioeconomy development across institutional, supply, demand, and biomass-related dimensions. Empirical data were collected through semi-structured expert interviews with key stakeholders in the region, allowing for a systematic assessment of enabling and constraining factors shaping the FBEE in this Southern European context (

Table 1).

2.1. Thematic Focus

In line with the focus of this study on the development of the FBEE, the analysis emphasized the institutional, supply, and demand-related drivers of the framework. Some drivers have been adapted to the understanding of entrepreneurial ecosystems in forest-based bioeconomy.

Although the analytical framework proposed by Barañano et al. [

12] provides a robust basis for evaluating the development of FBB across European regions, its original formulation is oriented towards systemic assessment of sectoral capacities—particularly in terms of biomass valorization, institutional coordination, and policy implementation. Given that the present study focuses on the enabling and constraining conditions for entrepreneurship and innovation in FBBE within Castilla-La Mancha, a selective adaptation of the framework has been applied to align with the specific research objectives and empirical scope.

Table 2 summarises the adapted, operational definitions.

This adaptation is theoretically grounded in the convergence between regional innovation systems [

32] and the entrepreneurial ecosystems perspective [

18,

19], both of which emphasize the interplay between institutional, cultural, and relational dimensions in fostering entrepreneurship. In this light, rather than offering a static evaluation of sectoral structures, the analysis seeks to understand how regional configurations—networks, policies, resources, and actors—interact to generate entrepreneurial dynamics, particularly in emerging and structurally disadvantaged territories.

Three main adjustments were introduced:

The “Green Public Procurement” dimension has been reframed into “Public–Private Collaboration”. While public procurement is a relevant mechanism for stimulating innovation, interview data and institutional context in Castilla-La Mancha revealed a more general concern with the effectiveness of collaborative governance and coordination between public and private actors. Therefore, this category was reformulated to capture a broader spectrum of interaction, including informal partnerships, joint initiatives, and institutional co-design mechanisms.

The “Regional Networks” dimension has been transformed into “Regional Ecosystem Governance”. The original framework emphasizes formal regional networks as enablers of system integration. However, empirical evidence pointed to the critical, yet underutilized, role of existing institutional structures—especially sectoral roundtables—in articulating the ecosystem. Accordingly, this driver was adjusted to better assess the operational capacity and strategic function of these coordination arenas.

Finally, the biomass-related driver, which assesses technical aspects such as resource availability, sustainability, and utilization potential, was not included in this analysis. This decision reflects the study’s focus on the institutional and entrepreneurial dynamics rather than the bio-physical dimension of the sector.

This tailored framework remains consistent with the systemic and multidimensional logic proposed by Barañano et al. yet reorients it toward a more actor-centered and innovation-driven analysis. It thereby enhances the framework’s applicability to studies concerned with the emergence and consolidation of forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystems in peripheral or transitioning regions.

2.2. Sample Design and Selection

The data were collected through a series of semi-structured interviews that were originally designed to explore the conditions for the development of the FBEE and innovation dynamics in the region.

The sample was purposefully designed to include key stakeholders with in-depth knowledge and direct involvement in institutional and entrepreneurial dynamics shaping the FBEE in Castilla-La Mancha.

Selection criteria included: (1) representing at least one of the main stakeholder groups involved in the regional forestry sector and bioeconomy (public officials, forest managers, companies, entrepreneurs, research centres, associations, etc.); (2) having participated in institutional or innovation-related dynamics in the sector, such as sectoral roundtables, innovation networks, entrepreneurship programs (e.g., UFIL Cuenca), or public–private collaboration spaces; (3) holding a strategic role in national or supranational institutions with potential influence over innovation financing or policy frameworks relevant to the development of the forest-based bioeconomy in Castilla-La Mancha.

Recruitment started from a predefined actor list (compiled from sectoral roundtable membership lists, UFIL partner registers and association directories) and was complemented by targeted snowballing to fill specific gaps—most notably forest owner associations, firms and demand-side actors (e.g., public procurement). We also allowed multiple interviews within the same organisation when interviewees held different roles/units, to capture intra-institutional heterogeneity. Between June and November 2024, we approached 22 different organisations, from which 12 finally participated.

Participating organisations and interviewees spanned four stakeholder groups, that conform to the quadruple helix of innovation: public administration (n = 1), associations/foundations (n = 6), firms (n = 3), and universities/research institutions (n = 2).

In terms of interviewees, we invited 20 stakeholders; 15 individuals from 12 organisations accepted, including three interviewees from CESEFOR and two from the regional government (JCCM). We purposively included CESEFOR as a neighboring orchestrator that functions as a mature intermediary and an aspirational benchmark for UFIL, enabling comparative insights while mitigating gatekeeper bias through broader recruitment across owners, SMEs, and demand-side actors. The government (JCCM), as one of the driving forces behind the initiative, fulfils forest management roles in the region, but also acts as a coordinating authority of UFIL. Of the 15 participants, 4 were directly affiliated with UFIL partner organisations (JCCM, FSC, UCLM, UPM) and none of them were beneficiaries of UFIL-supported activities. To guard against gatekeeper or halo effects, we broadened recruitment beyond UFIL-linked stakeholders. The following table (

Table 3) presents an overview of the interviewed stakeholders, detailing their institutional affiliations and roles within the forest-based bioeconomy ecosystem.

This sampling strategy was considered appropriate to capture a diverse range of perspectives on the key enabling and constraining factors for FBEE development in the region, and to ensure relevance to the study’s research questions and objectives.

2.3. Interview Process and Data Processing

A total of 15 semi-structured interviews were conducted using the Zoom platform (the standard, auto-updating commercial version available at the time of the interviews), with informed consent obtained from all participants for the recording and analysis of the interviews. The resulting transcripts were automatically generated and subsequently manually validated by the research team to ensure accuracy.

The interviews were semi-structured, including three control questions and ten thematic questions, organized around key analytical areas derived from an adapted version of the framework of Barañano et al. [

12].

For the analysis, a deductive thematic analysis was conducted, using the analytical framework of Barañano et al. [

12] as the coding structure. Relevant excerpts from the transcripts were identified and organized according to the key drivers of forest-based bioeconomy development proposed in the framework. This process was supported by iterative comparison of responses across stakeholders to enhance consistency and depth of interpretation.

To complement the thematic coding analysis and provide a comparative lens across drivers, we evaluate the ecosystem effectiveness using an ordinal scoring system. This scoring mechanism serves as a heuristic tool to synthesize stakeholder perceptions into structured assessments, ranging from 1 (no presence) to 5 (full consolidation). Each score reflects the level of systemic maturity of the ecosystem along each driver and was derived from qualitative indicators such as frequency and depth of references, consensus among stakeholders, and the presence of concrete institutional mechanisms or practices.

For each driver, we compiled an evidence grid with five qualitative indicators: (i) frequency (presence across interviews), (ii) consensus/divergence, (iii) tone (negative/mixed/positive), (iv) conceptual depth (shallow/moderate/deep), and (v) concrete mechanisms/examples (e.g., roundtables with KPIs, framework PPPs, pilots, green procurement, certification/traceability). We then applied a two-step decision rule: first, we selected the anchor level (1–5) that best matched the modal evidence (

Table A1); second, we applied a ±0.5 adjustment only if warranted—+0.5 when at least one formal mechanism was in place, −0.5 when evidence was thin/contradictory. Final scores are rounded to 0.5 and documented with anchor quotes.

This hybrid approach combines the depth of qualitative insight with the clarity and comparability of semi-quantitative assessment, enabling a more holistic evaluation of the ecosystem’s enabling and constraining conditions. The full scoring framework and methodological rationale are detailed in

Appendix A.

3. Results

The interviews reveal a complex and uneven landscape marked by a combination of promising opportunities and systemic constraints that shape the development of a forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem (FBEE) in Castilla-La Mancha.

One of the most frequently mentioned constraining factors concerns (1) government plans and policies. The interviewees highlight coordination failures as one of the most significant issues, emphasising the absence of a coherent and strategic regional policy for forest-based innovation and entrepreneurship. While some sectoral initiatives—such as projects in biomass, resin, or essential oils—have emerged, they are perceived as isolated actions, disconnected from a broader vision. The absence of a formal policy framework, “there is no master plan”, aligned with long-term goals and stakeholder needs is consistently cited as a critical limitation. This lack of institutional coordination is seen to hinder the activation of latent innovation potential and to reduce the visibility and legitimacy of the forest-based bioeconomy agenda within the region. The prevailing tone was strongly negative, and the critiques were conceptually substantive.

In terms of (2) research, development and innovation capacities, though present in some segments, are largely considered incipient and fragmented. Several stakeholders identify the Urban Forest Innovation Lab (UFIL Cuenca) as a promising catalyst, enabling new initiatives and activating local entrepreneurial talent, serving as a hub. However, even these efforts are seen as fragile and insufficiently supported by systemic mechanisms. Respondents note the absence of dedicated innovation infrastructures, sustained funding, and inter-institutional collaboration, which prevents the scaling of successful cases. These limitations contribute to a perception that innovation in the sector remains more aspirational than established. The tone of the interviews is mixed: positive about the potential and specific initiatives like UFIL, but negative regarding the lack of systemic support and the prevailing traditional mindset. Several interviewees link the innovation gap to underlying market failures (thin competitive pressure and weak demand signals) indicating conceptual depth in their diagnosis.

Regarding (3) training and talent, human capital also represents a major structural constraint. There is widespread concern about the low levels of professionalization within the forestry sector, with critical gaps identified not only in technical forestry skills but also in entrepreneurial competencies, market orientation, and management capabilities: “Training often lacks a ‘business vision’… that’s the big flaw in the current training system” (I03). Educational offerings are considered misaligned with the evolving demands of the sector, and the lack of economically viable conditions further weakens retention of skilled professionals. Some of the interviewees link the lack of talent to unattractive working conditions and proposes mechanisation as a solution: “If we mechanize the forest, young people will like the forest” (I05). While some interviewees refer to promising initiatives such as short training programmes and specialized academies, these are still in early stages and do not yet meet the scale of the challenge. Overall, the tone is negative, but the conceptual depth is moderate to deep, indicating structural disincentives in the regional labour market.

From the perspective of (4) ecosystem for entrepreneurship, most respondents agree that Castilla-La Mancha does not yet have a functional entrepreneurial ecosystem in the forest-based bioeconomy: “

Everyone fights their own wars. I don’t think that’s an ecosystem” (I01). Although Cuenca has emerged as a focal point for innovation through projects like UFIL [

33,

34], the overall picture is one of fragmentation, weak articulation among actors, and poor cross-sectoral collaboration: “

UFIL is a ‘small ecosystem’ that has worked… it is a meeting point” (I08). The region’s innovative business fabric is described as embryonic, and there is a general lack of shared platforms or support structures capable of orchestrating collective learning, investment, and strategy. The tone is negative with a positive undertone regarding UFIL Cuenca, with a moderate conceptual depth, not diving into ecosystem-specific elements.

One of the key enablers identified is the existence of (5) public-private collaboration mechanisms, albeit limited in scope and institutionalization. Interviewees value UFIL Cuenca as a rare example of effective public intervention that has mobilized entrepreneurs and support organizations. However, they also point out that such initiatives are too dependent on specific funding cycles and lack continuity. Broader regional collaboration is often contrasted with more advanced models in other territories, such as Galicia, where institutional frameworks like XERA enable more cohesive and long-term cooperation. Interviewees propose concrete improvements, such as the “demolition of bureaucratic barriers” I01 and the creation of a “one-stop shop” I14 to streamline procedures. Structural barriers—including insufficient public funding, fragmented governance, and a weak collaborative culture—further constrain the scaling of these efforts. This lack of market understanding provides a negative tone and a deep understanding of the needs to improve public-private collaboration.

A similar ambivalence is reflected in (6) regional governance networks, particularly the Sectoral Roundtables. These spaces are widely perceived as underutilized and ineffective, with limited convening power and low operational follow-up: “Those roundtables, as they are configured […] are not very operative. Basically, we are like stone guests” I01. Nonetheless, nearly all interviewees see potential in transforming these forums into genuine platforms for strategic coordination, diagnosis, and shared action. This reflects a broader recognition that the region needs not only innovative entrepreneurs but also governance mechanisms that can support and align collective efforts. Interviewees express a tone of frustration and disappointment, viewing the roundtables as purely informational and performative rather than functional governance bodies with deep and detailed critiques and concrete proposals for reform.

The (7) entrepreneurial capacities observed across the region are heterogeneous. Some actors, particularly those with access to research networks or European funding, demonstrate proactive innovation through digitalization, technological traceability, and ecosystem-based business models. These entities often operate as facilitators of innovation for other smaller players, offering services or acting as demonstration projects. In contrast, many other actors express more constrained views, noting that what innovation exists is often “forced” rather than strategic driven by regulatory compliance or market survival rather than by vision or differentiation. A major weakness identified at the firm is the lack of a business and market-oriented mindset: “They lack the vision and the incorporation of a certain degree of innovation, not only in the private sector but also in the public sector” I10. Other barriers such as lack of skilled labour, limited access to capital, and insufficient support for early-stage ventures are frequently mentioned. Several positive examples of highly capable firms are cited, but the overall tone is negative regarding the sector’s general state, with deep discussions linking firm-level capacities to broader systemic issues (such as mechanisation in improving firm-level productivity).

With regard to the (8) existence of cluster dynamics, most interviewees identify UFIL Cuenca as the most visible and successful initiative in the region’s forest-based bioeconomy, acting as a not yet embedded proto-hub although the sector is described as fragmented and individualistic: “Weak and fragmented…there is no way to create cohesion. Everyone works for themselves and on their own things. There is no collaborative or cooperative concept” I14. They describe it as a key actor with the potential to act as a cluster nucleus, serving multiple roles: talent incubator, innovation catalyst, platform for inter-institutional collaboration, and conduit between research and market. Stakeholders emphasize its function as a connector and activator of entrepreneurial culture, with the capacity to bridge gaps between isolated actors and domains. However, concerns remain about its limited institutional integration and overreliance on temporary funding schemes. Several interviewees advocate scaling up UFIL Cuenca to create a region-wide innovation hub comparable to entities like Cesefor and XERA, which operate in the Spanish regions of Castilla y León and Galicia, respectively. The lack of formal clusters provides a negative tone, in contrast with the highly positive tone concerning UFIL Cuenca’s potential. Specific understanding of clusters’ functions is articulated by interviewees: joint management, aggregating supply and knowledge sharing.

Finally, market awareness and demand (9) appear as driven by market-linked innovations that extend beyond technological advances. There is growing interest in mechanisms such as carbon credit markets, ecosystem service compensation, and the creation of transparent trading platforms for forest products. Some stakeholders emphasize the need to leverage digital tools—such as blockchain and remote sensing—to provide objective carbon traceability, aligning forest management with climate-related market demands. Others highlight structural changes like the anticipated surge in wood demand, the rise of timber construction, identified as a major future driver of demand for wood: “The construction sector […] must avoid, mitigate, and reduce 2 major impacts. One impact is the waste it generates […] and secondly, the reduction of its carbon footprint” (I14) and the integration of forestry with other sectors (e.g., tourism, education, health). These expectations reveal a strategic awareness of market opportunities, yet they also underscore the sector’s current limitations in adapting to demand signals. There is a strong emphasis on the need to “unite supply with demand” I03. This involves understanding the specific needs of industry so that forest owners can produce accordingly. Overall, the tone is mixed: negative about today’s limited market vision and alignment, but positive/optimistic about near-term opportunities in construction and emerging markets. The conceptual depth is moderate-to-deep, with respondents linking instruments (traceability, trading, ES markets) to concrete market dynamics.

The development of a robust FBEE in Castilla-La Mancha is currently shaped by a tension between significant enabling assets (such as existing pilot initiatives, regional entrepreneurial ambition, and underexploited ecological resources) and entrenched structural constraints (

Table 4).

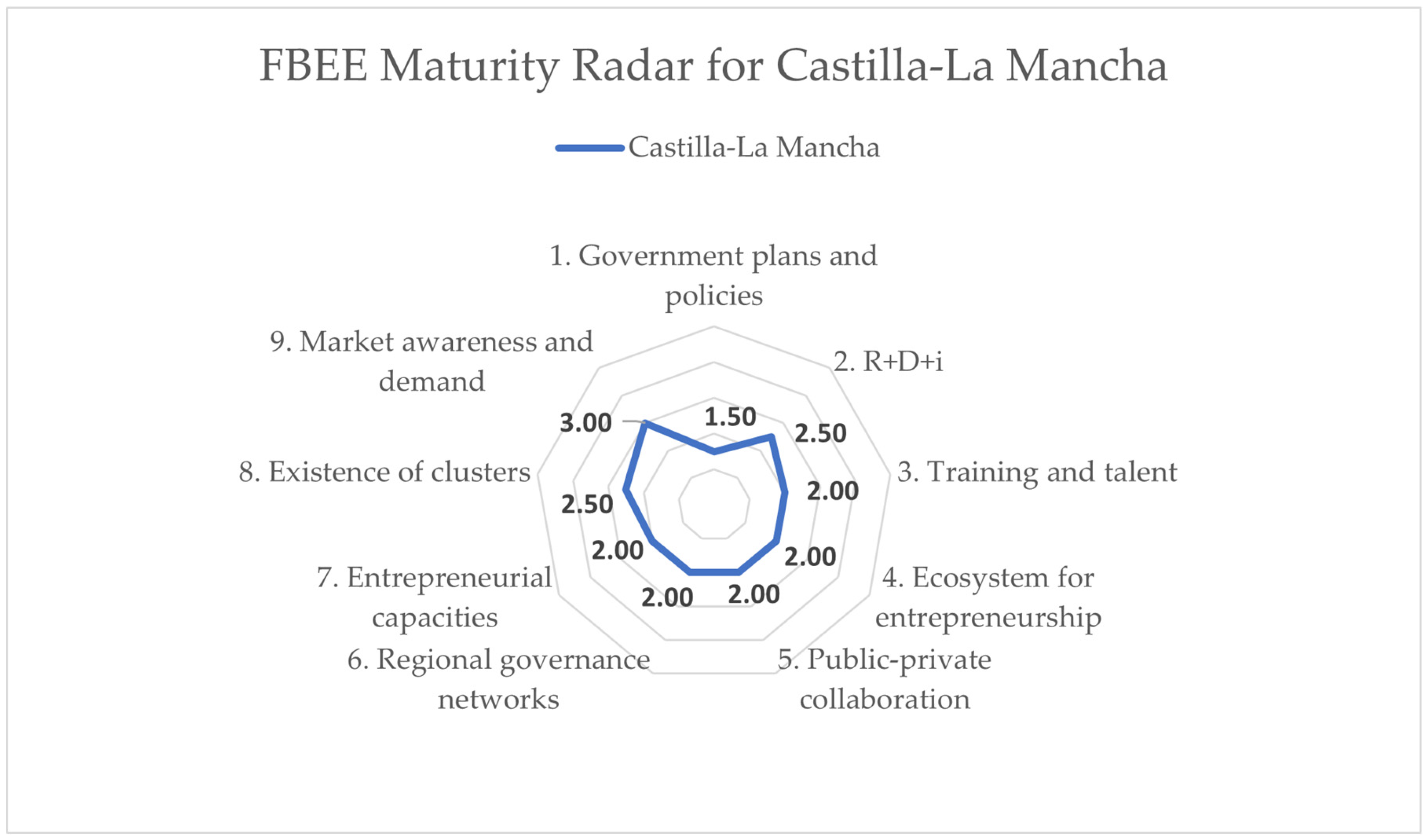

Following the scoring criteria to the nine drivers (

Appendix A), we obtain a FBEE maturity average of 2.17/5, with a median of 2.0 and a narrow IQR of 2.0–2.5, indicating clustered low maturity. Only one driver reaches 3.0 (market awareness), while two-thirds (6/9) remain at ≤2, consistent with an incomplete ecosystem constrained by weak strategy, governance and PPPs. A ±0.5 sensitivity analysis preserves both the demand–institutional gap and the driver ranking, indicating robustness of conclusions despite the ordinal nature of the scale. As a resume, the main issues are the lack of a coherent regional strategy, weak institutional coordination, limited human capital and inadequate support mechanisms for entrepreneurship and innovation.

Figure 1 summarises FBEE maturity in Castilla–La Mancha (0–5 scale). The profile is low-to-mid overall and markedly asymmetric. The lowest score is Government plans and policies (1.5), indicating the absence of a structured, widely known strategy. A broad plateau at 2.0 spans Ecosystem for entrepreneurship, Public–private collaboration, Regional governance networks, and Entrepreneurial capacities, signalling thin coordination and limited capability depth. R + D + i and Existence of clusters sit slightly higher (2.5), consistent with emergent initiatives (e.g., UFIL) but still short of a cohesive system. The only comparatively stronger area is Market awareness and demand (3.0), reflecting clearer anticipation of market/technology shifts than the ecosystem’s present ability to mobilise around them.

4. Discussion

The analysis reveals that the institutional landscape in Castilla-La Mancha does not yet provide the systemic alignment necessary to foster a robust forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem (FBEE). Despite the growing recognition of the bioeconomy as a driver for sustainable regional development [

3,

5,

35], the case of Castilla-La Mancha exemplifies a gap between conceptual commitments and institutional praxis. While some enabling initiatives and territorial assets exist, the absence of cohesive policies, fragmented governance structures, and underdeveloped support systems represent significant limitations to the emergence of a dynamic and innovative forest-based economy.

As Barañano et al. [

12] stress, institutional coordination and government strategy are foundational for FBEE development. However, the findings suggest that in Castilla-La Mancha, regional policies remain fragmented and fail to provide an integrated roadmap for forest-based innovation. Sector-specific projects—such as those in resin, biomass, or essential oils—are perceived as isolated and disconnected from broader developmental goals. This disarticulation reduces institutional legitimacy and the ability to mobilize actors around a shared vision. Furthermore, the absence of strategic alignment weakens the region’s capacity to activate its latent innovation potential [

13].

This misalignment also reflects the lack of dedicated innovation infrastructures, including incubators, accelerators, and sustained funding channels. As Kuckertz et al. [

13] note, innovation in the bioeconomy requires not only individual entrepreneurial agency but also enabling environments that reduce risk and encourage experimentation. In Castilla-La Mancha, such environments remain under construction. While initiatives such as UFIL Cuenca demonstrate potential as catalysts for innovation, they lack sufficient structural support. Their success remains precarious due to temporary funding and weak institutional embedding. The situation in Castilla-La Mancha exemplifies the limitations of what Spigel [

19] would describe as an “incomplete ecosystem,” where critical support infrastructures are underdeveloped or ephemeral.

Despite efforts to promote specialized training (e.g., UFIL Cuenca trainings), the forestry sector still suffers from low levels of professionalization. As highlighted in the interviews, technical and managerial competencies are insufficiently addressed in current educational frameworks. This divergence limits both the entrepreneurial and absorptive capacities of the territory [

18], weakening its ability to adapt to new value chains and market opportunities, a pattern consistent with evidence for other Spanish regions [

12].

Moreover, without economically viable prospects in the forestry sector, talent retention remains a key challenge. This reveals a vicious cycle in which limited profitability undermines the development of human capital which, combined with the migration dynamics established in the region [

30], extracting talent from the region in a brain-drain effect and constrains innovation and entrepreneurship. In effect, the ecosystem falls into a capability trap: weakened skills and routines reduce its ability to generate returns and renew itself, thereby reproducing low entrepreneurial dynamism [

18,

19,

31].

Institutional arrangements such as Sectoral Roundtables, while formally in place, are widely regarded as ineffective. Their limited operational capacity and lack of follow-up mechanisms prevent them from becoming true platforms for strategic coordination. This finding is consistent with Theodoraki & Messeghem’s [

20] assertion that governance structures must go beyond formal existence and exhibit functionality and legitimacy. Operational governance could reduce transaction costs and increase the rate of multi-actor projects and new firms creation. Some interviewees recognized the potential of these forums to evolve into governance hubs, but this would require a cultural shift towards institutionalized collaboration and co-design. Currently, collaboration depends more on individual relationships than on durable inter-organizational mechanisms.

Although the region does not yet possess a fully consolidated forest-based business ecosystem, the data point to the existence of initiatives with catalytic potential, such as UFIL Cuenca. According to interviewees, this program has acted as a bridge between entrepreneurs, public administration, and knowledge centres, helping to articulate projects and develop entrepreneurial skills. While its reach remains limited and localized, it is recognized for its potential to catalyse collaborative networks and facilitate knowledge transfer in the absence of structured governance and innovation mechanisms.

Additionally, the region benefits from underutilized forest resources, a growing awareness of ecosystem service markets (e.g., carbon credits), and interest in new value chains such as biomaterials or wood construction. These conditions offer potential for strategic innovation, but without institutional mechanisms to coordinate investment, knowledge transfer, and regulatory alignment, these assets remain underexploited. Public-private partnerships and demand-side instruments (e.g., green procurement [

12]) could reduce risk market entry and accelerate adoption of forest-based innovations.

5. Conclusions

The case of Castilla-La Mancha illustrates shows that the region’s forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem remains at a low-maturity stage: valuable ecological assets, emerging initiatives such as UFIL Cuenca, and rising interest in bioeconomic innovation are not yet embedded within a coherent strategic and organisational framework. The lack of an integrated regional policy, weak institutional coordination, and underdeveloped support infrastructures constrain the transition to a more resilient and dynamic ecosystem.

In relation to the set research objectives, this study shows that (i) the development of the FBEE in CLM is conditioned by a variety of enablers (valuable ecological assets, emerging pilot initiatives such as UFIL, and growing interest in bioeconomic innovation) and constraints (absence of an integrated regional policy, weak institutional coordination, and underdeveloped support infrastructures) that keep the ecosystem at a low-maturity stage; (ii) The alignment between strategies and regional conditions is partial and insufficient. Existing initiatives are not yet embedded in a coherent strategic framework capable of scaling up innovation and entrepreneurship; and (iii) UFIL Cuenca operates as a catalyst for innovation and capacity building. However, its effect remains limited until it is scaled up, networked and integrated into the sector’s governance structures.

Empirically, the study provides evidence from a Southern European rural region on how proto-hub initiatives can coexist with weak systemic embedding. Methodologically, it shows the usefulness of a structured, multi-driver diagnostic to reveal coordination and capability bottlenecks. Taken together, the results indicate that progress towards a mature forest-based bioeconomy in CLM will require synchronised advances across institutional, supply, demand, and resource dimensions.

Future research should further explore effective governance models for emerging FBB ecosystems in peripheral and rural regions and examine how initiatives like UFIL Cuenca can be scaled or replicated to drive systemic transformation, enabling future cross-regional comparisons, demonstrating the value of entrepreneurship support programs in catalysing innovation and talent development in the forest sector. Scaling such models regionally—through replication, networking, and integration with sectoral governance structures—would amplify their transformative potential. Additionally, more attention should be paid to the role of entrepreneurial ecosystems as critical enablers of the forest-based bioeconomy, particularly in Southern European and Mediterranean contexts that remain underrepresented in current scholarship.

The following sections outlines limitations of the study and specific policy recommendations to support the development of a more cohesive and dynamic forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem in Castilla-La Mancha.

5.1. Limitations

This single-case, qualitative study faces three limitations. First, sample composition: the number of firms and owners’ associations is limited, which may over-represent public/association viewpoints. Second, potential bias linked to UFIL visibility (some interviewees are affiliated/beneficiaries), possibly inflating its assessed role. Third, the ordinal index is heuristic; while triangulated with mention counts and quotes, it remains sensitive to coder judgement.

Future work should expand firms and owner associations sampling, including additional regions, and applying inter-coder procedures at scale. UFIL-linked participation (direct affiliates, 4/15) may inflate perceptions of UFIL’s role. We mitigated this risk through diversified recruitment, but readers should interpret UFIL-specific insights with this caveat in mind.

5.2. Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations can be proposed to foster the development of a more cohesive and dynamic forest-based entrepreneurial ecosystem in Castilla-La Mancha.

First, it is critical that the regional government of Castilla–La Mancha (JCCM) develop a comprehensive regional strategy for the forest-based bioeconomy through an inter-departmental taskforce, aligned with European and national bioeconomy frameworks. This strategy should articulate clear objectives, priority areas for innovation, and coordination mechanisms to overcome current fragmentation and provide long-term guidance to both public and private actors. In this regard, strengthening public-private collaboration and supporting cluster formation would be key to enhancing entrepreneurial capacities in the sector.

Second, existing sectoral networks should be reinforced and professionalized as core platforms for stakeholder coordination and strategic governance. As highlighted by interviewees, these spaces must evolve beyond their current consultative role to become operational forums for shared diagnosis, co-creation, and policy influence. For achieving it, the regional government should look for representativity from administration, businesses, forest owners, research institutions, and civil society. Regional government or a specialized firm with territorial animation capabilities could achieve this evolution through regular meetings, actionable agendas, and robust monitoring systems are needed to ensure their effectiveness and impact.

Additionally, targeted investments in training and capacity building, particularly for young entrepreneurs and rural stakeholders, are needed to bridge current human capital gaps and foster a vibrant and inclusive FBEE in CLM.

These findings not only contribute to the academic understanding of forest-based bioeconomy transitions in Southern European contexts but also highlight practical implications for policymakers and stakeholders.