Abstract

The ability to accurately assess the impact of organic soil drainage on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) is still limited. Methane (CH4) emissions are characterized by significant variations, and GHG emissions from nutrient-rich organic soil in the region have not been extensively studied. The aim of this study was to assess CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from nutrient-rich organic soil in hemiboreal forests to provide insights into their role in regional GHG balance. Over the course of one year, CH4 and N2O emissions, as well as their affecting factors, were monitored in 31 forest compartments in Latvia in both drained and undrained nutrient-rich organic soils. The sites were selected to include forests of different ages, dominated by silver birch (Betula pendula Roth), Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karsten), and black alder (Alnus glutinosai (L.) Gärtner), as well as clearcuts. Soil GHG emissions were estimated by collecting gas samples using the closed manual chamber method and analyzing these samples with a gas chromatograph. In addition, soil temperature and groundwater level (GW) measurements were conducted during gas sample collection. The mean annual CH4 emissions from drained and undrained soil were −4.6 ± 1.3 and 134.1 ± 134.7 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1, respectively. N2O emissions from undrained soil (4.1 ± 1.4 kg N2O ha−1 year−1) were significantly higher compared to those from drained soil (1.7 ± 0.6 kg N2O ha−1 year−1). In most of the study sites, undrained soil acted as a CH4 sink, with the soil estimated as a mean source of CH4, which was determined by one site where an emission hotspot was evident. The undrained soil acted as a CH4 sink due to the characteristics of GW level fluctuations, during which the vegetation season GW level was below 20 cm.

1. Introduction

In northern regions, including the hemiboreal forest, organic soil, especially peatlands with a high C content, makes understanding the soil greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions particularly important [1]. Peats are formed by partially decomposed biomass litter that is stored in anoxic conditions due to a high groundwater level. The continuous supply of labile organic matter by the natural mortality of biomass and seasonality of groundwater level fluctuations can determine the proportion of soil layers with aerobic and anaerobic conditions and regulate conditions that are suitable for microbial activities, either by producing GHG or removing them from the atmosphere.

According to a common understanding, the drainage of organic soils reduces CH4 emissions and increases N2O emissions. In general, N2O emissions from rewetted organic soils are considered negligible [2], while there is evidence that N2O can have an important role in GHG emissions from hemiboreal drained peatlands due to its high global warming potential [3] of 265 [4]. It has been estimated that the establishment of a natural GW level in northern peatlands increases CH4 emissions (global warming potential of 28 [4]) on average by 46% [5]. To further signify the role of CH4 emissions from wet soils, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has reported that, globally, natural wetlands contribute 25%–40% to the emissions of CH4 [6], while drained peatlands contribute up to 5% of GHG emissions [7]. However, estimations of the annual emissions of both CH4 and N2O are still highly uncertain [8] as studies conducted so far cannot provide empirical data of sufficient temporal and spatial coverage to enable highly and accurately drained organic soil GHG emission estimates. An understanding of naturally wet (undrained) organic soil is even more scarce, which likely originates from no obligations to report GHG emissions from undrained soil according to IPCC Guidelines. However, to evaluate the actual anthropogenic impact of drainage on climate change, the GHG balance can be estimated as the difference between emissions from undrained and drained land.

The synthesis and analysis of exercises by IPCC and reported in the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for Wetlands Supplement [2] provided default emission factors for GHG inventories and showed that there was no significant difference between CH4 emissions from undrained and rewetted organic soil, and a variance in the emission factors for both soils range within −0.1 to 420 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1. Furthermore, CH4 emissions from nutrient-rich organic soils were estimated to be half an order of magnitude higher than those from nutrient-poor organic soils. Similarly, a 95% confidence interval of emission factors for the drained nutrient-rich organic soil ranged more than 100% around the mean from negative to positive values. However, the above-mentioned use of default emission factors could not provide sufficiently accurate emission estimates at the national level for a confident understanding of CH4 emissions from drained and undrained/rewetted organic soils.

Our research aimed to assess CH4 and N2O emissions from both drained and undrained nutrient-rich organic forest soil in hemiboreal Latvia. In addition to conducting emission measurements, we evaluated emission-affecting factors to explore possibilities for finding solutions to improve the accuracy of emission estimates by upscaling based on local conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site Description

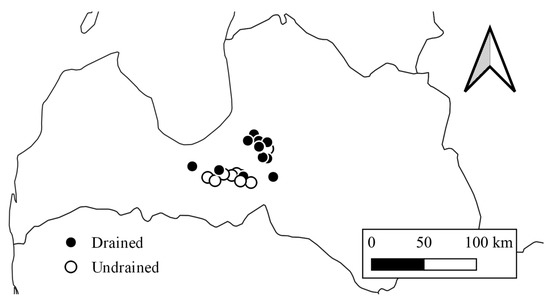

This study was conducted in hemiboreal forest sites in central Latvia (Figure 1) with undrained (Dryopterioso-caricosa and Filipendulosa) and drained (Oxalidosa turf. Mel.) nutrient-rich organic soil according to the national forest site type classification [9]. In total, 31 study sites, including 5 clearcuts and 26 forest stands with dominant tree species of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth), black alder (Alnus glutinosai (L.) Gärtner), and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karsten) (hereafter birch, alder, and spruce, respectively) at various developmental stages were included in this study (Table 1). Respectively, subsequent references to tree species in relation to the measurements indicate the dominant tree species in the study sites and, accordingly, also in the respective sample plots, as these were established in an area representative of the study sites. Each study site was represented by one circular sample plot (500 m2), which was established at least 50 m from the border of the forest site and at least 300 m and 100 m from the nearest drainage ditch in undrained and drained sites, respectively. The selected drained sites were representative of typical national drainage practices, and the drainage systems were functional. The sample plots represent the same forest sites (Table 1) used for the estimation of the soil carbon I budget by a previous study [10].

Figure 1.

Locations of the study sites in Latvia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sites [10].

To confirm the comparability of the selected drained and undrained sites, soil sampling and analysis were performed. For the characterization of soil properties, 100 cm3 of undisturbed samples of the soil layer depths from 0 to 10 cm and from 10 to 20 cm were collected by the core method [11] in two replicates of each sample plot and were analyzed by an ISO 17025-certified laboratory [12] using ISO standard methods. The differences between the average values of soil bulk density and the chemical properties of the soil characteristics were recalculated from a 0 to 20 cm depth in the study sites where drained and undrained soil were not statistically significant (Table S1). The data acquired for the characterization of the study sites were further used to evaluate their impact on estimated soil GHG (CH4 and N2O) emissions.

2.2. GHG Emission Sampling and Analysis

Soil GHG emissions were monitored for 12 consecutive months in each of the sample plots between October 2019 and June 2021. During the monitoring period, annualized mean air temperature (+9.2 ± 0.8 °C) was slightly higher, but precipitation (668 ± 136 mm) corresponded to the Latvian climate standard norm of +6.8 °C and 685.6 mm, respectively [13]. To estimate instantaneous soil GHG emissions, gas samples were collected by the manual static closed opaque chamber method [14] with an interval of four weeks and were analyzed with a gas chromatograph [15] in the ISO 17025-certified laboratory.

For the collection of gas samples, five chamber collars were installed evenly spread across the sample plot to measure instantaneous soil emissions in five replicates during each of the study site surveys. Collars were installed at a soil depth of five centimeters to avoid root damage and leave the ground vegetation and litter layer undisturbed. Gas sampling was performed at an interval of four weeks, starting at least one month after the installation of the collars. Sampling during the same time of day in the plots was avoided by randomizing the sample plot visiting sequence. In each collar position, gas samples were collected immediately after positioning the chamber on the collar and in three additional replicates with an interval of 10 min. The samples were collected in underpressurized (0.2 mbar) glass bottles (100 mL) and transported to the laboratory. Concentrations of CH4 and N2O in the samples were determined using a gas chromatograph Shimadzu Nexis GC-230 equipped with FID and ECD detectors and operated by the software LabSolutions. During gas sampling, soil (in five centimeters depth) and air temperature, as well as the groundwater level using a PVC pipe installed vertically at the soil depth of 140 cm, were measured.

2.3. GHG Emission Estimation

For the calculation of soil GHG emissions, a linear regression analysis was performed using data on GHG concentrations in the chambers. Data points that did not follow the trends in concentration changes were excluded from the analysis. The slope coefficients of equations with R2 < 0.7 were excluded from the estimation of soil GHG emissions, except for occasions when the uncertainty of the gas chromatography method exceeded the difference between the maximum and minimum gas concentration values. The obtained slope coefficients of linear equations, which described changes in the GHG concentration in the chamber during gas sampling, were used to calculate soil GHG emissions.

where emissions represent the instantaneous soil GHG emissions, µg CH4 or N2O m−2 h−1; M is the molar mass of CH4 or N2O (16.04 g mol−1 or 44.01 g mol−1, respectively); R is the universal gas constant, 8.314 m3 Pa K−1⋅mol−1; P is the assumption of air pressure inside the chamber, 101,300 Pa; T is the air temperature, K; V is the chamber volume, 0.063 m3; the slope is the GHG concentration’s changes over time (the slope coefficient), ppm h−1; and A is the collar area, 0.1995 m2.

To estimate soil emissions during the study site survey, the mean of five instantaneous emission measurement replicates was calculated. It was assumed that monthly emission measurements represented the cumulative soil emissions of the corresponding month of gas sampling. Consequently, annual soil GHG emissions were estimated as the sum of cumulative monthly emission values.

2.4. Data Evaluation

To evaluate spatial, temporal, and cumulative variations, the soil emission coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated. The CV of monthly measurements within a single study site was used to express temporal variation, while for spatial variation, CV was calculated using the mean measured emissions in drained or undrained study sites. To express spatial and temporal cumulative variation, CV was calculated using all monthly measurement results within the drained or undrained sites. The uncertainty of the results was expressed as a 95% confidence interval if not stated otherwise. The relationship strength between GHG emissions and the affecting factors was expressed by the Pearson (r) or Spearman (ρ) correlation coefficient. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the differences between these two data groups. Statistical analyses were carried out, and figures (packages corrplot and ggplot2) were prepared using software R. In the boxplots, the median was shown by a bold line; the mean was shown by a cross; the box corresponded to the lower and upper quartiles; and whiskers showed minimal and maximal values (within 150% of the interquartile range from the median).

3. Results

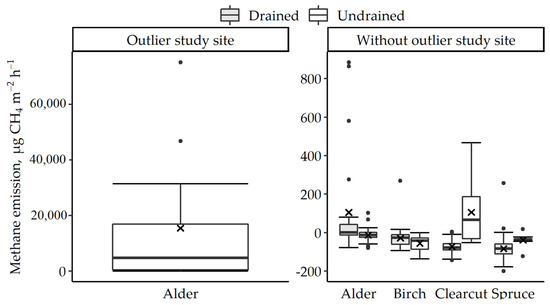

3.1. Instantaneous CH4 Emissions

The measured within-site mean instantaneous CH4 emissions ranged from −109 ± 44 to 44 ± 214 µg CH4 m−2 h−1 in sites with drained soil (mean −53 ± 14 µg CH4 m−2 h−1) and from −69 ± 36 to 7.6 × 103 ± 23.7 × 103 µg CH4 m−2 h−1 in undrained sites (mean 1.5 × 103 ± 1.6 × 103 µg CH4 m−2 h−1), as shown in Figure 2. Such high values of emission measurement results in the undrained sites were introduced by one sample plot (hereafter, an outlier study site). If data from this site were excluded, instantaneous emissions measured in the undrained sites ranged from −72 ± 24 to 65 ± 104 µg CH4 m−2 h−1, thus not exceeding the range of emissions in the drained sites considerably. Furthermore, only two out of ten study sites with undrained soil—alder stand and clearcut—were measured as a mean source of CH4 emissions at 15.5 × 103 ± 13.4 × 103 and 106 ± 94 µg CH4 m−2 h−1, respectively. In the rest of the study sites, undrained soil tended to remove CH4 from the atmosphere: the mean instantaneous emissions were measured at −32 ± 38 µg CH4 m−2 h−1. In the case of drained sites, the soil in two out of twenty-one sample plots acted as a source of CH4 emissions. Specifically, the average value of emission measurements in a birch sample plot and a black alder sample plot was 5 ± 52 and 236 ± 193 µg CH4 m−2 h−1, respectively. Thus, the obtained results indicated that among the stands with different dominant tree species, soil CH4 emissions tended to be higher in the alder stands. The empirical data suggest that, in national conditions, undrained soil is typically not a source of CH4 emissions, although the occurrence of emission hotspots could make the soil a net emitter overall. The results emphasize the importance of being aware of the increased spatial variability and probability of CH4 emission hotspots in undrained areas when upscaling emission estimations.

Figure 2.

Variation in the instantaneous CH4 emission measurement results.

3.2. Uncertainty of the Instantaneous CH4 Emissions

The statistical outliers of instantaneous CH4 emission measurement results (values below −187 and above 85 µg CH4 m−2 h−1) were identified during 3% and 12% of the field surveys in three study sites with drained and four sites with undrained soil, respectively. The mean of the drained and undrained soil emission outlier values was 419 ± 357 and 13.4 × 103 ± 21.7 × 103 µg CH4 m−2 h−1 in the drained and undrained sites, respectively. Excessive outlier emissions (mean 20.6 × 103 ± 25.6 × 103 µg CH4 m−2 h−1) were measured during 9 out of 12 sample plot surveys in the outlier study site. If data from the outlier study site were excluded, the mean outlier emissions from undrained soil (263 ± 142 µg CH4 m−2 h−1) was lower than the mean of outlier CH4 emissions from the drained soil.

The uncertainty of the measured instantaneous CH4 emissions was not uniform across the depth range of the GW level. By evaluating the soil CH4 emissions in gradation classes of the GW level, it could be clearly seen that the uncertainty of emissions was significantly greater when the GW level was below 20 cm. Most (90%) of the emission outlier values exceeding 85 µg CH4 m−2 h−1 were measured when the collar was flooded, and the GW distance from the soil surface was less than 20 cm. The CV of CH4 emissions in the drained sites ranged from 7 to 30% when the GW level was below 20 cm, but when GW depth ranged from 0 to 20 cm and when the soil was flooded, CV was 92% and 57%, respectively. In undrained sites, the variation was higher, ranging from 20 to 39%, when the GW level was below 20 cm. When the GW level was higher than 20 cm, CV was 112%; however, the flooded soil was 203%.

The spatial variation in CH4 emissions in the drained and undrained sites was 130% and 320%, respectively, while the mean temporal variation in the emissions of the study sites was 90 ± 180% in the drained sites and 330 ± 540% in the undrained sites. Cumulative spatial and temporal variation in the undrained sites (560%) was more than two times higher compared to the drained sites (210%).

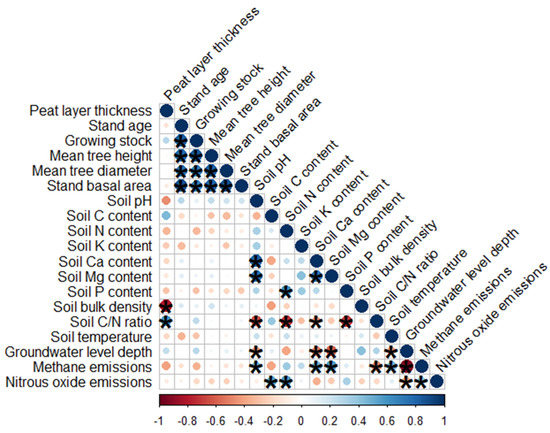

3.3. CH4 Emission-Affecting Factors

A significant correlation (p < 0.05) was found between CH4 emissions, soil Ca (ρ = 0.5) and Mg (ρ = 0.6) concentrations, soil temperature (ρ = 0.3), pH (ρ = 0.5), and the C/N ratio (ρ = −0.5); however, the correlations were weak to moderate (Figure 3). The empirical data indicate a direct linear relationship between the soil temperature and soil CH4 removals and how, irrespective of the soil’s temperature, removals of the undrained soil tended to be higher by 26 µg CH4 m2 h−1 compared to the undrained soil. However, due to a weak correlation for both drained and undrained soils, the inclusion of soil temperature as a variable in CH4 emission prediction models could not significantly improve the prediction power. The main predictor of soil CH4 emissions is the GW level, which is indicated by a strong correlation (ρ = −0.9) between individual measurements of GW depth and instantaneous CH4 emissions.

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation analysis of the soil annual GHG emissions and affecting factors (soil parameters at depth of 0–20 cm are evaluated). Size and color of the bubbles indicate correlation strength; starred bubbles show significant (p ≤ 0.05) correlations.

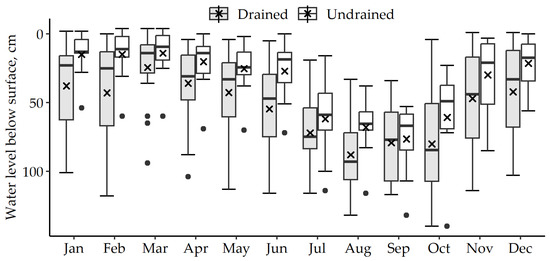

During the study period, the GW level depth in the drained and undrained sites was, on average, 55 ± 2 cm and 35 ± 3 cm, respectively. The variation in the GW level depth’s monthly measurements was slightly higher in the undrained sites (CV = 82 ± 34%) compared to the drained sites (CV = 64 ± 23). The monthly mean GW level in sites with drained soil was, on average, 19 ± 4 cm lower compared to the GW level in the undrained sites, and the difference in the average was rather consistent throughout the year (Figure 4). The highest monthly mean difference in the GW level depth (29 ± 9 cm) was found in drained and undrained clearcuts. In drained and undrained sites, the GW level was above 20 cm at 24% and 42% of the filed surveys, when a highly increased variation in CH4 emissions could be expected. By contrast, during the vegetation season (mean measured air temperature above 5 C°), the GW level in both the drained and undrained sites was above 20 cm during around 15% of the field surveys.

Figure 4.

Variation in groundwater level depth of the study sites.

The soil’s CH4 removals decreased as the GW level rose to around 20 cm in depth; further increasing the GW level could gradually cause the soil to become a net source of CH4 emissions. However, the magnitude of net emissions was greatly affected by the temporal and spatial emission uncertainty. If outliers of the CH4 emission measurement results were excluded, the relationship between GW depth and CH4 emissions could be explained by the polynomial equation:

where y represents instantaneous CH4 emissions, µg CH4 m2 h−1; and x is the GW level below the surface, cm. The equation determined that CH4 removals increased from −2 to −96 µg CH4 m2 h−1 when the groundwater level decreased from 0 to 100 cm below the soil surface level. If the uncertainty of the model was considered (RMSE = 35 µg CH4 m2 h−1), the soil could become a CH4 source when the GW level was near the 20 cm level.

y = 0.0049x2 − 1.435x − 1.964

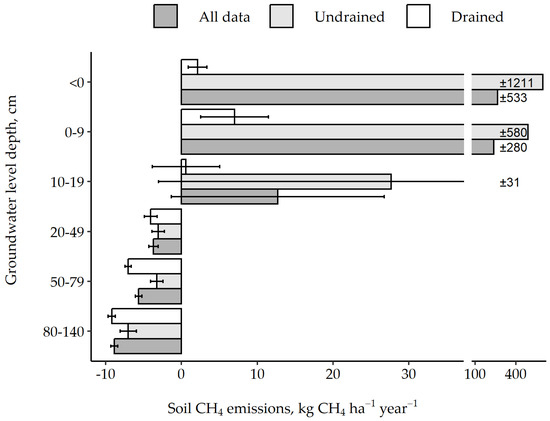

If outliers of the CH4 emission measurement results were not excluded, the mean instantaneous CH4 emissions measured were 1331 ± 1481 µg CH4 m2 h−1 when the GW level ranged from the soil surface to a depth of 20 cm; however, when the GW level was deeper, the mean measured emission value was −67 ± 3 µg CH4 m2 h−1. When the data were stratified by their drainage status, considerable differences in the mean instantaneous net CH4 emissions were identified when the GW level was shallower than 20 cm. However, it must be noted that this difference was introduced by the outlier study site. When the soil was flooded, or the GW level was in the ranges of 0 to 9 cm or 10 to 19 cm below the surface, the mean measured soil CH4 emissions in the drained sites were 24 ± 14, 80 ± 51, and 7 ± 51 µg CH4 m2 h−1 (total mean 37 ± 39 µg CH4 m2 h−1), respectively, but in undrained sites, the emissions amounted to 6.8 × 103 ± 13.8 × 103, 5.6 × 103 ± 6.6 × 103, and 315 ± 350 µg CH4 m2 h−1 (total mean 4.2 × 103 ± 6.9 × 103 µg CH4 m2 h−1). When the GW level was deeper than 20 cm below the surface, the mean measured soil CH4 removals stratified by the GW level depth levels indicated in Figure 4 ranged from 46 to 105 µg CH4 m2 h−1 in the drained sites and from 35 to 80 µg CH4 m2 h−1 in the undrained sites (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Soil CH4 emissions stratified by groundwater level depth classes.

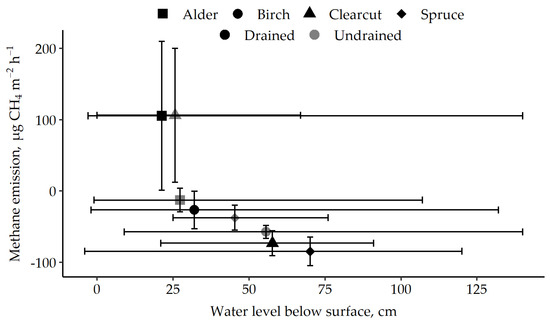

The results of the measured instantaneous soil CH4 emissions and GW level stratified by the drainage status and dominant tree species or clearcut showed that the undrained sites tended to have a narrower range in the GW level variation while also showing a similar variation in CH4 emissions (Figure 6). This could be observed because, while in the drained sites GW reached deeper levels below the surface, such sites tended to have a high or even higher GW level upper threshold than in the undrained sites. If the outlier study site was excluded, on average, the drained alder stands and undrained clearcut were a mean source of CH4 emissions amounting to 105 ± 104 and 106 ± 94 µg CH4 m2 h−1, respectively. By contrast, the soil in the rest of the study site groups ensured CH4 removals from the atmosphere. In drained birch, the clearcut and spruce sites, which measured the mean soil CH4 removal, were 27 ± 26, 73 ± 17, and 85 ± 20 µg CH4 m2 h−1, respectively. In undrained alder, the spruce and birch stands that measured the mean CH4 removals were 13 ± 17, 37 ± 18, and 57 ± 9 µg CH4 m2 h−1, respectively. Thus, the results indicate that an increase in the measured mean GW level from 27 to 70 cm could increase the mean instantaneous soil CH4 removals from 13 to 85 µg CH4 m2 h−1, while sites with a measured mean GW level of 21 and 26 cm were a source of the mean 106 µg CH4 m2 h−1.

Figure 6.

Range of the GW level depth and standard deviation of measured instantaneous CH4 emissions in study sites stratified by dominant tree species or clearcut and drainage status. Vertical wicks show a range of standard deviations around the mean of measured instantaneous CH4 emissions. Horizontal wicks show the range (min and max values) of the measured GW level around the mean value. Data from the outlier study site are excluded.

3.4. Annual Soil CH4 Emissions

The estimated annual CH4 emissions from soil in drained sites ranged from −10.9 to 20.4 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (mean −4.6 ± 1.3 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) and from –8.7 to 1355 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (mean 142.1 ± 134.7 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) in undrained sites. The study results indicated the tendency of higher CH4 emissions from the soil in alder stands, with mean annual emissions of 9.1 ± 22.1 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 and 266.4 ± 524.3 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 from drained and undrained soil, respectively. The mean negative soil CH4 emissions of drained and undrained soil in the study stands of dominant tree species of birch were not significantly different (mean −5.9 ± 1.6 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1). In spruce stands, the estimated CH4 emissions were −7.3 ± 1.3 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 from drained soil and −3.2 ± 1.6 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 from undrained soil (Table 2). The clear influence of the drainage status on soil emissions in clearcuts (all site means −3.2 ± 6.1 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) could not be recognized with high confidence, as the undrained site was represented by one study site with estimated annual emissions of 6.9 ± 6.2 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1. However, it could be emphasized that soil in all the drained clearcuts ensured CH4 removal from the atmosphere.

Table 2.

Annual soil CH4 emissions, kg CH4 ha−1 year−1.

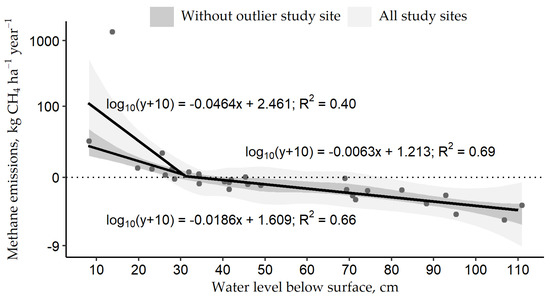

The mean value of GW level measurements in the study sites had a moderate (r = −0.64) and a strong (r = −0.88) correlation to the estimated annual net soil CH4 emissions, considering and excluding the study site with an extreme annual cumulative emission value, respectively. Accordingly, the mean GW level and annual emissions had a similar correlation as the results of an individual GW level and instantaneous CH4 emission measurement results. Therefore, annual soil CH4 emissions could be expressed as a function of the mean GW level (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Relationship between estimated annual soil CH4 emissions and the measured mean GW level in the study sites. A 95% confidence interval around the smooth local regression was indicated.

Two depth ranges of the mean GW level could be distinguished—above and below 31 cm. For GW levels deeper than 31 cm, the linear regression lines overlapped regardless of whether an extreme annual emission value was considered in the analysis. However, when the GW level was shallower than 31 cm, the extreme value of annual CH4 emissions significantly affected the slope coefficient of the linear regression equation.

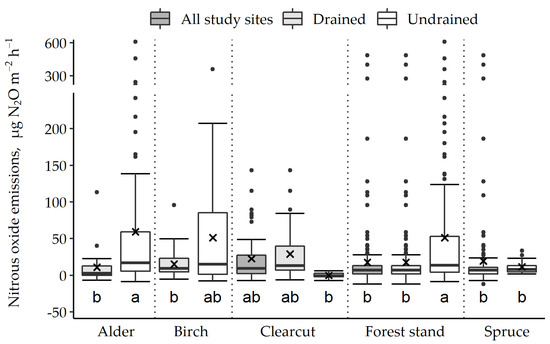

3.5. Soil N2O Emissions

The measured mean instantaneous N2O emissions from the drained soil ranged from 0.6 ± 0.6 µg N2O m2 h−1 in alder stands to 26.9 ± 23.3 µg N2O m2 h−1 in clearcuts (Figure 8). The emissions from undrained soils ranged from the mean 0.0 ± 1.8 µg N2O m2 h−1 in clearcut to the mean 59.2 ± 71.8 µg N2O m2 h−1 in alder stands. In birch and alder stands, as well as in clearcuts, the soil moisture regime had a significant effect on the mean instantaneous soil N2O measurement results, while in spruce stands with drained and undrained soil, the mean value of the emission measurements did not differ significantly. The mean measured N2O emissions from drained soil in the birch, alder, and spruce stands were 15.1 ± 5.9, 11.0 ± 9.7, and 19.6 ± 10.8 µg N2O m2 h−1, respectively, which was not significantly different. In the study sites with undrained soil, the situation was the opposite, where the measured mean emissions in birch (51.1 ± 26.2 µg N2O m2 h−1), spruce (11.5 ± 5.9 µg N2O m2 h−1), and alder (59.4 ± 27.3 µg N2O m2 h−1) stands were significantly different from each other (Figure 8). The mean soil N2O emissions from drained (19.7 ± 7.2 µg N2O m2 h−1) and undrained (46.6 ± 16.1 µg N2O m2 h−1) soil were significantly different.

Figure 8.

Variation in the instantaneous N2O emission measurement results. Different lowercase letters show statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

When the outlier values of soil N2O instantaneous emission measurements were excluded, changes in the soil temperature explained 44% of the variation in emissions. The soil temperature measurement results of the drained soil showed a moderate correlation (r = 0.5) with the emission measurements, whereas the temperature measurements of undrained soil showed a weak correlation. The linear regression analysis suggested that a 10 °C rise in the soil temperature could result in an average increase of 9 µg N2O m2 h−1 in soil N2O emissions. However, the regression equations developed without considering extreme emission measurements could lead to an underestimation of soil emissions. The inclusion of outliers indicated that both the soil temperature and GW level measurements had a weak correlation (r = −0.3) with soil N2O instantaneous emissions.

No clear influence on the soil drainage status of annual soil N2O emissions was observed in forests with different dominant tree species (Table 3). The difference between annual soil N2O emissions in the drained sites (mean 1.7 ± 0.6 kg N2O ha−1 year−1) and undrained sites (mean 4.1 ± 1.4 kg N2O ha−1 year−1) was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Annual soil N2O emissions, kg N2O ha−1 year−1.

A moderate correlation (ρ = −0.4) was observed between the average groundwater level measurements and the estimated annual soil N2O emissions in individual plots. The annual soil N2O emissions were significantly (p < 0.05) correlated with soil C (ρ = 0.5), N (ρ = 0.65), and P (r = 0.5) concentrations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Instantaneous Soil CH4 Emissions and Affecting Factors

The measured negative mean instantaneous CH4 emissions from drained and undrained soil in most of the study sites suggested that the categorization of land by the existence of drainage systems alone might not be sufficient to accurately characterize the actual emissions from such areas using fixed emission factors. This study confirmed the general knowledge that the GW level was the main factor explaining soil CH4 emissions. However, the results of soil instantaneous CH4 emissions stratified by soil drainage status pointed out that drainage had a role in determining the patterns of soil emissions. In other words, the emissions from the soil with the same GW level depth could have a different behavior due to emission heterogeneity depending on whether the soil was drained or not. Previous studies have suggested that the reasons for varied soil emission patterns of drained and undrained soil could have been impacted by differences in the soil microbial (structure of methanogens and methanotrophs) [16,17,18] and ground vegetation conditions (presence of aerenchymatous species) [19,20,21,22,23], as well as the different characteristics of soil-to-atmosphere CH4 transportation mechanisms (diffusion, ebullition) [24,25,26].

The GW level plays a key role in determining the thickness of soil layers with aerobic and anaerobic conditions, as well as the proportion of microorganisms that produce or consume CH4 [21]. According to common general knowledge, the possibility of oxidizing all of the produced CH4 is limited by the aerobic soil layer width [27]. Several studies have shown that the activity of methanotrophs can considerably reduce soil CH4 emissions [19,20,28] or even consume most of the soil CH4 emissions [18,29,30,31], which can be indirectly supported by our observations. Our study underlined the significance of the GW level depth threshold of around 20 cm, acting as a balance between net instantaneous CH4 removals and emissions. If outliers are considered, in most of our study sites, irrespective of their drainage status, a soil layer of at least 20 cm with aerobic conditions was evidently sufficient for methanotrophs to fully offset CH4 emission production. The capabilities of the 20 cm layer of soil with aerobic conditions to oxidize most or all of the CH4 before it was released into the atmosphere was demonstrated by peatlands in Wales, United Kingdom [29]. However, in drained soil with a lower GW level than the mentioned GW threshold, higher net CH4 removals could be expected, but with a similar uncertainty for undrained soil. By contrast, if the GW level was higher than the threshold, the emissions could be equally small from both drained and undrained soil; however, this study suggested there was a probability of detecting considerable emission outlier values in undrained soils. Such hotspots cannot be ignored as they could determine undrained soil to be an overall mean source of CH4 emissions.

According to previous studies, a GW level shallower than 20 cm could be associated with significant CH4 emissions from soil in peatlands and bogs in temperate and boreal regions [21]. Studies have shown that when the GW level is either shallower or deeper than 20 cm from the soil surface, the estimated range of CH4 emissions from peatlands in the boreal zone was from −1.7 to 525 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (mean 56 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) and from −1.1 to 51 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (mean 86 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1), respectively [21]. However, in our case, the results indicated that significant emissions when the GW level was shallower than 20 cm could be related to the occurrence of emission hotspots, which are characteristic of undrained soils specifically. As with a GW level between 0 and 19 cm, the mean measured instantaneous CH4 emissions from drained soil (3.5 ± 3.2 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) was considerably lower; however, undrained soil (248 ± 279 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) emissions were considerably higher compared to previous studies. This observed increase in CH4 emissions was likely set by the impact of CH4 transport on ebullition and through aerenchymatous vascular plants, determining the occurrence of outlier emissions. Excessive CH4 emissions observed in one of the undrained study sites (mean 20.6 ± 25.6 mg CH4 m2 h−1) were not unprecedented. Similarly, 15.5 mg CH4 m−2 h−1 emissions after three episodes of ebullition were observed in the northern peatlands [24]. However, in our case, the cause of such emissions was not identified or recorded.

The reason for net CH4 removal patterns observed in most of the study sites could be introduced by local conditions inhibiting the activity of methanogens or promoting CH4 oxidation by methanotrophs. It was identified that an increase in CH4 removals with increasing soil temperature was not typical. In general, it was assumed that an increase in the soil temperature could contribute to an increase in soil net CH4 emissions; however, the impact of temperature on the balance of methanogenesis and methanotrophy is variable and uncertain [26,31,32,33,34] and could potentially vary according to different local conditions. Although there is a reason to suspect that the tendencies identified could be faulty because of a low correlation, such a phenomenon may have been introduced by the impact of the soil’s physical and chemical parameters [17] or by sphagnum characteristics of the study sites. It was observed that the removal of the sphagnum layer could increase CH4 emissions fivefold [35], which was related to CH4 oxidizing symbiotic bacteria in peat moss ecosystems, which could potentially fully oxidize diffusive-transported CH4 [33]. It was studied and found that such a methanotrophic process was activated in an environment of high groundwater level [35] and increased soil temperature [33,35]. It may be the reason behind the observed tendency of soil temperature and net CH4 removals.

4.2. Uncertainty of Soil CH4 Emissions

This study highlights the importance of quantifying spatial and temporal heterogeneity and the extent of soil CH4 emission hotspots. Although this observation was based on 10 study sites, the results roughly indicated that emission hotspots with multiple orders of magnitude higher than the overall mean CH4 soil emissions could be present in 10% of forest sites with undrained soil, which may be uncommon. Although these conditions were different, it is notable that in another study, it was estimated by chamber measurements nested within the footprint of Eddy covariance that 10% of saturated peatland areas in the Nordic region (wet polygonal tundra) accounted for up to 45% of total CH4 emissions [36]. Higher spatial coverage of emission measurements could give higher confidence for the current observations of spatial heterogeneity. Additionally, temporal heterogeneity was more attributed to undrained soils. There was a four times higher chance of measuring outlier CH4 emissions in undrained sites than in drained sites.

The role of different dominant tree species on the probability of the occurrence of excessive emissions was not assessed with certainty. It could not be excluded that the observation of higher soil emissions in both drained and undrained black alder stands was impacted by high spatial variability and, in general, not specifically by the dominant tree species. The results of various studies indicated that the variability of CH4 emissions was determined by microtopographic properties [21,37] and the impact of microrelief on soil hydrology [38,39,40]. However, such topographic properties of the study sites were not evaluated.

4.3. Annual Soil CH4 Emissions and Issues of Interpretation and Upscaling

The estimated annual mean CH4 emissions from drained organic soil (−4.6 ± 1.3 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) were below the threshold of a 95% confidence interval (−1.6 to 5.5 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) of the IPCC default emission factors for the boreal zone (mean 2.0 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) [2]. However, estimated removals were close to the range of measured CH4 emissions from drained organic soil in Finland: from −3.7 to 15.6 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 in forest site types classified with nutrient-poor and nutrient-rich soil, respectively [41]. The estimated mean annual CH4 emissions from undrained organic soil (142.1 ± 134.7 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) corresponded to the IPCC default EF for the boreal zone (182.7 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) with a confidence interval from 0 to 657.3 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 [2].

The differences in elaborated emission factors within these studies can likely be explained by varying soil conditions, particularly the patterns of GW fluctuations and mean GW levels, as well as the differences in vegetation and possibly microbial characteristics. Therefore, the use of fixed emission factors calculated as the mean of results from various studies could introduce a considerable error when used to upscale emissions from an area of interest. As discussed above, in general, this uncertainty was introduced by outlier emissions, which were measured when the GW level was higher than 20 cm. High spatial heterogeneity and the ability of a relatively small area with excessive soil emissions to have a significant impact on the total emissions observed in this and previous studies [42] signifies the problem of upscaling the study results of soil CH4 emissions to areas with similar conditions on a country or even a local scale, as well as the verification of upscaled emissions. The current capabilities to acquire spatial data, enabling the possibility to predict locations of emission hotspots, were limited. The review of the studies in the boreal zone showed that CH4 emissions in peatlands with a GW level distance from the surface less than 20 cm ranged from −1.7 to 164 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (mean 24 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) in areas with aerenchyma plants and from a mean of 12 to 123 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1 (range from 3.1 to 525 kg CH4 ha−1 year−1) in areas with no such plants [21]. Another study in an abandoned peat extraction site estimated that the leaf area density of aerenchyma plants (Eriophorum vaginatum and Scheuchzeria palustris) could explain 91% of the spatial variation in CH4 emissions [43]. Therefore, the considerably increased uncertainty of CH4 emission estimations at high GW levels could be reduced by incorporating parameters that account for the presence of plants with aerenchyma in the emission prediction models [21], as well as by the elaboration of methods that could potentially provide spatial information on the GW level depth or at least identify areas with saturated soil [44,45,46]. Information on the spatial distribution of aerenchyma plants could be especially useful when predicting CH4 emissions in conjunction with geographical data on areas with a GW level close to the surface of the soil. The limitation of acquiring such data on a country scale could be the remote sensing resolution restricting the identification of small areas with excessive emissions; hence, the upscaling of such hotspots could become inaccurate if remote sensing classification cannot resolve small-scale vegetation heterogeneity identification issues [36].

The results this study acquired could be upscaled by data on the average GW level in areas of interest. The average GW level could be used to predict annual soil CH4 emissions, as methanogenic and methanotrophic microorganisms are adapted to withstand adverse conditions and remain abundant at a specific depth below the soil surface, regardless of fluctuations in the groundwater level [22,47,48]. This was confirmed by a correlation found between the mean GW and estimated annual CH4 emissions in our study. This, in conjunction with the GW fluctuation observed in the study sites, indicates how crucial it is to consider the actual groundwater level when estimating emissions, especially in undrained areas and rewetted areas, where similar increased emission uncertainties and hotspot probabilities are expected [49]. Our study clearly shows that in national conditions, although the mean GW level in undrained study sites was higher compared to the drained sites, during the vegetation season, it was below 20 cm, which is an obvious threshold of the groundwater level that determines if the soil is a source or sink of the measured mean instantaneous net CH4 emissions. This was the main determiner that most sites, irrespective of the drainage status, were not a source during the study period.

However, it must be considered that the GW level alone could not predict the occurrence of an emission hotspot. For this reason, future studies of CH4 emissions should include an examination of microbiology and vegetation in the study sites. Emissions upscaled by mean GW level data should be validated to increase their confidence and reduce uncertainties in the scaling procedures [36] by either the addition of point measurements only or preferably in combination with landscape emission measurement methods. Ideally, the choice of a validation-measurement-point geographical location should be chosen by remote sensing solutions, which can be used to predict the groundwater level depth and vegetation cover to optimize the use of resources for the elaboration of CH4 emission upscaling solutions. Although this study did not find a significant impact of soil temperature on CH4 emissions, which is common, using temperature as a limiting factor in upscaling annual soil emissions could reduce the risk of overestimating emissions in the winter. It has been observed that soil CH4 emissions are significantly limited at temperatures below −5 °C [21].

4.4. Soil N2O Emissions

Previous studies have revealed a wide range of mean instantaneous soil N2O emissions from drained histosols, varying from 0.6 to 342 µg N2O m2 h−1 [50]. Thus, it indicates that these soils can serve as both minor and major sources of emissions, introducing challenges that can upscale the study results of N2O emissions at a regional or country level. The mean instantaneous emissions in individual study sites with drained and undrained soil did not exceed 67 and 131 µg N2O m2 h−1, respectively. However, estimated annual emissions were found to be rather consistent in both the drained and undrained sites.

The annual mean soil N2O emissions from drained and undrained sites (1.7 kg N2O ha−1 year−1) were found to be slightly below the 95% confidence interval (from 3.0 to 7.1 kg N2O ha−1 year−1) of the default emission factors elaborated by the IPCC for the nutrient-rich soil in the boreal zone [2]. However, this could be explained by conditions characteristic of hemiboreal forests, as previous studies have shown that farther to the south, drained organic soil could also ensure N2O removals from the atmosphere, i.e., a lower confidence interval range of the IPCC default emissions factor for a temperate zone was estimated and showed that negative emissions of −0.9 kg N2O ha−1 year−1 could occur [2]. Furthermore, while IPCC Guidelines consider N2O emissions from rewetted organic soil to be negligible, in our study, the estimated mean of N2O emissions from undrained sites was twice as high as the estimated mean in drained sites. A possible explanation for increased emissions from undrained soil could be introduced by denitrification [51].

No correlation between N2O emissions and soil moisture and temperature was recognized in our study or by previous studies [3,50]. Accordingly, the use of estimated annual emissions as an emission factor for country-scale emission estimates could be appropriate. The evaluation of previous studies’ results has suggested that the soil C/N ratio could be used to upscale N2O emissions [50,52] as the rates of mineralization and nitrification in forest soils rise with a decreasing C/N ratio [53,54]. Furthermore, an exponential increase in emissions could be expected if the C/N ratio tended to be lower than around 15 [50]. In our case, the C/N ratio ranged from 13 to 31 (mean 19) in individual study sites, and the correlation between the C/N ratio and annual N2O emissions was low. For instance, C/N was below 15 in 30% of the study sites; however, no association with increased emissions was observed. Comparably higher emissions measured in alder stands could be introduced by species’ capabilities to fixate nitrogen, therefore, increasing nitrogen availability for N2O emission production [55,56].

5. Conclusions

Regardless of the soil drainage status, soil in the majority of research sites ensured CH4 removal from the atmosphere during the study period. Drained soil provided CH4 removal consistently, while undrained soil showed considerably higher spatial and temporal emissions variability and hotspot occurrence probabilities, which determined that undrained areas could be a considerable source of CH4 emissions overall. The difference in the mean groundwater levels between drained and undrained sites was consistent, but observations indicated that groundwater level differences in clearcut sites could be considerably larger. Drainage in clearcut sites resulted in a lowered groundwater level to facilitate CH4 uptake by the soil. The soil in undrained clearcut sites was a source of CH4 emissions, suggesting that drainage could prevent the soil from becoming a CH4 source in clearcuts.

The groundwater level is the main factor affecting CH4 emissions. Therefore, when estimating soil CH4 emissions at a regional or national level, it is recommended that the relationship between the estimated annual emissions and average groundwater level or the relationship between emissions and groundwater level classes is used. It should be noted that the average groundwater level could not predict the occurrence of CH4 emission hotspots. Therefore, future studies aiming for more accurate emissions of upscaling solutions should also include a vegetation evaluation. By combining such knowledge with remote sensing methods to determine the groundwater levels and vegetation cover, more accurate CH4 emissions predictions could be expected.

This study did not identify relationships between N2O and the studied environmental variables that would allow for emissions modeling. However, it was found that, although emissions from nutrient-rich organic soils are minor, emissions are significantly higher in undrained research sites compared to drained sites. Considering the comparably small measurement variability observed in this study, the use of fixed emission factors for drained and undrained sites in national or stand-wise emission estimations could be appropriate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f14071390/s1, Table S1: Soil properties in 0 to 20 cm depth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.; methodology, A.L. and A.B. (Aldis Butlers); validation, A.B. (Arta Bārdule); formal analysis, A.B. (Aldis Butlers), S.K. and D.P.; investigation, G.S. (Gints Spalva) and G.S. (Guntis Saule); resources, A.L.; data curation, A.B. (Aldis Butlers); writing—original draft preparation, A.B. (Aldis Butlers) and D.P.; writing—review and editing, A.B. (Arta Bārdule) and A.L.; visualization, A.B. (Aldis Butlers); supervision, A.L.; project administration, S.K.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) project “Evaluation of factors affecting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction potential in cropland and grassland with organic soils”, grant number 1.1.1.1/21/A/031 and “Development of greenhouse gas emission factors and decision support tools for management of peatlands after peat extraction”, grant number 1.1.1.1/19/A/064. The APC was funded by ERDF project number 1.1.1.1/19/A/064.

Data Availability Statement

Data, including the coordinates of the study sites, can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author via e-mail.

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Aldis Butlers is funded by the European Social Fund within the project (Nr. 8.2.2.0/20/I/001) “LLU Transition to a new funding model of doctoral studies”. The contributions of Arta Bārdule and Dana Purviņa are funded by the Fundamental and Applied Research Program project “Evaluation of factors affecting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from surface of tree stems in deciduous forests with drained and wet soils”, grant number LZP-2021/1-0137.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hugelius, G.; Tarnocai, C.; Broll, G.; Canadell, J.G.; Kuhry, P.; Swanson, D.K. The Northern Circumpolar Soil Carbon Database: Spatially Distributed Datasets of Soil Coverage and Soil Carbon Storage in the Northern Permafrost Regions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2013, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraishi, T.; Krug, T.; Tanabe, K.; Srivastava, N.; Baasansuren, J.; Fukuda, M.; Troxler, T. (Eds.) 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Viru, B.; Veber, G.; Jaagus, J.; Kull, A.; Maddison, M.; Muhel, M.; Espenberg, M.; Teemusk, A.; Mander, Ü. Wintertime Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Hemiboreal Drained Peatlands. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Mendoza, B.; Daniel, J.S.; Nielsen, C.J.; Rotstayn, L.; Wild, O. Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In Climate Change 2013—The Physical Science Basis Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; Volume 9781107057, pp. 659–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Hastings, A.; Truu, J.; Espenberg, M.; Mander, Ü.; Smith, P. Emissions of Methane from Northern Peatlands: A Review of Management Impacts and Implications for Future Management Options. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 7080–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofsy, S.C.; Zhang, X.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B. Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry. Carbon N. Y. 2007, 21, 499–587. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jauhiainen, J.; Alm, J.; Bjarnadottir, B.; Callesen, I.; Christiansen, J.R.; Clarke, N.; Dalsgaard, L.; He, H.; Jordan, S.; Kazanavičiūtė, V.; et al. Reviews and Syntheses: Greenhouse Gas Exchange Data from Drained Organic Forest Soils—A Review of Current Approaches and Recommendations for Future Research. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2019, 16, 4687–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bušs, K. Forest Ecology and Typology; Zinātne: Rīga, Latvija, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Butlers, A.; Lazdiņš, A.; Kalēja, S.; Bārdule, A. Carbon Budget of Undrained and Drained Nutrient-Rich Organic Forest Soil. Forests 2022, 13, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, N.; De Vos, B. Sampling and Analysis of Soil, Manual Part X; Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems: Eberswalde, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9783865761620. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence pf Testing and Calibration Laboratories. ISO/CASCO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Latvia’s Climate. Available online: https://videscentrs.lvgmc.lv/lapas/latvijas-klimats (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Pavelka, M.; Acosta, M.; Kiese, R.; Altimir, N.; Brümmer, C.; Crill, P.; Darenova, E.; Fuß, R.; Gielen, B.; Graf, A.; et al. Standardisation of Chamber Technique for CO2, N2O and CH4 Fluxes Measurements from Terrestrial Ecosystems. Int. Agrophys. 2018, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftfield, N.; Flessa, H.; Augustin, J.; Beese, F. Automated Gas Chromatographic System for Rapid Analysis of the Atmospheric Trace Gases Methane, Carbon Dioxide, and Nitrous Oxide. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.J.; Yavitt, J.B. Temperate Wetland Methanogenesis: The Importance of Vegetation Type and Root Ethanol Production. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Silva, N.; Sarria-Guzmán, Y.; Dendooven, L.; Luna-Guido, M. Methanogenesis and Methanotrophy in Soil: A Review. Pedosphere 2014, 24, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.S.; Hanson, T.E. Methanotrophic Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laanbroek, H.J. Methane Emission from Natural Wetlands: Interplay between Emergent Macrophytes and Soil Microbial Processes. A Mini-Review. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.; Pancotto, V.A.; Elzenga, J.T.M.; Visser, E.J.W.; Grootjans, A.P.; Pol, A.; Iturraspe, R.; Roelofs, J.G.M.; Smolders, A.J.P. Zero Methane Emission Bogs: Extreme Rhizosphere Oxygenation by Cushion Plants in Patagonia. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couwenberg, J.; Fritz, C. Towards Developing IPCC Methane ‘Emission Factors’ for Peatlands (Organic Soils). Mires Peat 2012, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Knorr, K.H.; Blodau, C. Impact of Experimental Drought and Rewetting on Redox Transformations and Methanogenesis in Mesocosms of a Northern Fen Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.D.A.; Evans, C.D.; Zielinski, P.; Levy, P.E.; Gray, A.; Peacock, M.; Norris, D.; Fenner, N.; Freeman, C. Infilled Ditches Are Hotspots of Landscape Methane Flux Following Peatland Re-Wetting. Ecosystems 2014, 17, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, P.H.; Chanton, J.P.; Morin, P.; Rosenberry, D.O.; Siegel, D.I.; Ruud, O.; Chasar, L.I.; Reeve, A.S. Surface Deformations as Indicators of Deep Ebullition Fluxes in a Large Northern Peatland. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2004, 18, GB1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Schulz-Hanke, M.; Alba, J.; Jurisch, N.; Hagemann, U.; Sachs, T.; Sommer, M.; Augustin, J. A Simple Calculation Algorithm to Separate High-Resolution CH4 Flux Measurements into Ebullition and Diffusion-Derived Components. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 2018, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, S.C. Natural Wetlands and the Atmosphere. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2005, 22, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askaer, L.; Elberling, B.; Glud, R.N.; Kühl, M.; Lauritsen, F.R.; Joensen, H.P. Soil Heterogeneity Effects on O2 Distribution and CH4 Emissions from Wetlands: In Situ and Mesocosm Studies with Planar O2 Optodes and Membrane Inlet Mass Spectrometry. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2254–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.M.E.; Clymo, R.S. Methane Oxidation in a Peatland Core the Ambient Air: 13CH4 Was Added at the Water Appeared in the Gas Space Before Each Headspace Gas Sampling • the Fan Was Turned On. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornibrook, E.R.C.; Bowes, H.L.; Culbert, A.; Gallego-Sala, A.V. Methanotrophy Potential versus Methane Supply by Pore Water Diffusion in Peatlands. Biogeosciences 2009, 6, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Stephen, K.D.; Nedwell, D.B.; Arah, J.R.M. Oxidation of Methane in Peat: Kinetics of CH4 and O2 Removal and the Role of Plant Roots. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1997, 29, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, R. Methane Production and Methane Consumption: A Review of Processes Underlying Wetland Methane Fluxes. Biogeochemistry 1998, 41, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horz, H.P.; Rich, V.; Avrahami, S.; Bohannan, B.J.M. Methane-Oxidizing Bacteria in a California Upland Grassland Soil: Diversity and Response to Simulated Global Change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2642–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winden, J.F.; Reichart, G.J.; McNamara, N.P.; Benthien, A.; Damsté, J.S.S. Temperature-Induced Increase in Methane Release from Peat Bogs: A Mesocosm Experiment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Conrad, R. Effect of CH4 Concentrations and Soil Conditions on the Induction of CH4 Oxidation Activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, N.; Van Winden, J.F.; Pan, Y.; Bodrossy, L.; Reichart, G.J.; Smolders, A.J.P.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Damsté, J.S.S.; Op Den Camp, H.J.M. Global Prevalence of Methane Oxidation by Symbiotic Bacteria in Peat-Moss Ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, T.; Giebels, M.; Boike, J.; Kutzbach, L. Environmental Controls on CH4 Emission from Polygonal Tundra on the Microsite Scale in the Lena River Delta, Siberia. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010, 16, 3096–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Kellomäki, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Shurpali, N.; Martikainen, P.J. Modeling CO2 and CH4 Flux Changes in Pristine Peatlands of Finland under Changing Climate Conditions. Ecol. Model. 2013, 263, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.J.; Podest, E.; Schroeder, R.; Pinto, N.; McDonald, K.C.; Glagolev, M.; Filippov, I.; Maksyutov, S.; Heimann, M.; Chen, X.; et al. Modeling the Large-Scale Effects of Surface Moisture Heterogeneity on Wetland Carbon Fluxes in the West Siberian Lowland. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 6559–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, K.; Kellomäki, S.; Zhang, C.; Martikainen, P.J.; Shurpali, N. Modeling Water Table Changes in Boreal Peatlands of Finland under Changing Climate Conditions. Ecol. Modell. 2012, 244, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Thornton, P.E.; Ricciuto, D.M.; Hanson, P.J.; Mao, J.; Sebestyen, S.D.; Griffiths, N.A.; Bisht, G. Representing Northern Peatland Microtopography and Hydrology within the Community Land Model. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 6463–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, P.; Minkkinen, K.; Penttilä, T. The Current Greenhouse Gas Impact of Forestry-Drained Boreal Peatlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 289, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresto Aleina, F.; Runkle, B.R.K.; Brücher, T.; Kleinen, T.; Brovkin, V. Upscaling Methane Emission Hotspots in Boreal Peatlands. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drösler, M. Trace Gas Exchange and Climatic Relevance of Bog Ecosystems. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovs, J.; Lupikis, A. Identification of Wet Areas in Forest Using Remote Sensing Data. Agron. Res. 2018, 16, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stals, T.; Ivanovs, J. Identification of Wet Areas in Agricultural Lands Using Remote Sensing Data. Res. Rural Dev. 2019, 1, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovs, J.; Stals, T.; Kaleja, S. Impact of the Use of Existing Ditch Vector Data on Soil Moisture Predictions. Res. Rural Dev. 2020, 35, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, A.; Kaitala, V.; Lehtinen, A.; Lohila, A.; Alm, J.; Silvola, J.; Martikainen, P.J. Methane Production and Oxidation Potentials in Relation to Water Table Fluctuations in Two Boreal Mires. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, N.; Fritz, C.; Langelaan, E.S.; Pan, Y.; Bodrossy, L.; Pancotto, V.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Smolders, A.J.P.; Op Den Camp, H.J.M. Methanotrophic Activity and Diversity in Different Sphagnum Magellanicum Dominated Habitats in the Southernmost Peat Bogs of Patagonia. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Blain, D.; Couwenber, J.; Evans, C.; Murdiyarso, D.; Page, S.; Renou-Wilson, F.; Rieley, J.; Strack, M.; Tuittila, E.S. Greenhouse Gas Emission Factors Associated with Rewetting of Organic Soils. Mires Peat 2016, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemedtsson, L.; Von Arnold, K.; Weslien, P.; Gundersen, P. Soil CN Ratio as a Scalar Parameter to Predict Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2005, 11, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernfors, M.; Rütting, T.; Klemedtsson, L. Increased Nitrous Oxide Emissions from a Drained Organic Forest Soil after Exclusion of Ectomycorrhizal Mycelia. Plant Soil 2011, 343, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernfors, M.; Von Arnold, K.; Stendahl, J.; Olsson, M.; Klemedtsson, L. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Drained Organic Forest Soils—An up-Scaling Based on C:N Ratios. Biogeochemistry 2008, 89, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, P.; Emmett, B.A.; Kjønaas, O.J.; Koopmans, C.J.; Tietema, A. Impact of Nitrogen Deposition on Nitrogen Cycling in Forests: A Synthesis of NITREX Data. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 101, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V.; Smith, M.L.; Martin, M.E.; Hallett, R.A.; Goodale, C.L.; Aber, J.D. Regional Variation in Foliar Chemistry and N Cycling among Forests of Diverse History and Composition. Ecology 2002, 83, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühlmann, T.; Caprez, R.; Hiltbrunner, E.; Körner, C.; Niklaus, P.A. Nitrogen Fixation by Alnus Species Boosts Soil Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou-Giesbrecht, S.; Menge, D.N.L. Nitrogen-Fixing Trees Increase Soil Nitrous Oxide Emissions: A Meta-Analysis. Ecology 2021, 102, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).